1. Introduction

Economic viability is necessary for the successful running of any system and network. All industries and infrastructure constructed for commercial purposes need to be economically viable, have a good economic model, and be adaptable and robust in design. These measures are necessary for a successful business. It should also have contingency plans in the case of rare but possible emergency events. Along with these, there is always a need to update, modernize, and push innovation. Most organizations that do not do this activity stagnate, face great market competition, and eventually default or declare bankruptcy. This is greatly problematic when this occurs within the State or Government. It becomes an economic weight, a load pulling the economy down as it cannot make profits, and leads to a loss in revenue. The above mention economic steps are necessary for essential services, such as electricity [

1].

Theft of resources has been an issue for as long as people have existed. It is the exploitation of the system for personal gain and through unfair means to profit or utilize resources that you have not paid for. The modern world has undergone many changes, especially regarding its power infrastructure. There has been consistent investment in the improvement and security of such facilities. With regards to the Third World economies, problems, such as a lack of investment, corruption, mismanagement, and innovation, have stagnated their electrical industry. This has halted progress or even reverted progress in some countries [

2].

Pakistan’s biggest problem regarding electricity is theft and the inability of managerial institutes to catch the perpetrators. This has been a source of encouragement for people to steal electricity as institutes have failed to mitigate theft. Most old and obsolete infrastructure security is easily compromised [

3]. There are many ways to tamper with electricity meters without consequence. The most common have been discussed below, and a case study comparing the existing to the newly proposed smart meters has had very promising results.

A system can never be 100% efficient; the electricity network is the same. Developed countries, such as the U.S.A., have a minimum of 1–2% electricity theft; in the U.K., the theft rate is approximately 8% [

4,

5]. This might look like a small amount, but in a multibillion-dollar organization, a lot of money is being stolen from the State or private organizations; some industries pass the bill to the other customers. The problem is that electricity theft is not because of one but a multitude of factors, some of them are social, ethical, ideological, etc. It is a fact that the world loses approximately 90 billion USD/year in electricity theft, most of which is from emerging energy markets. In 2014, about 60 billion USD were lost in new developing markets; these include Third World countries or developing countries [

6]. The countries with the highest electricity theft are India, Brazil, and Russia. In these countries, India has lost more electricity than Brazil and Russia combined. Pakistan is also very high on this list, having line losses greater than 15% [

7]. Among these, most are due to electricity theft. This results in great financial loss and, in some extreme cases, can lead to a huge circular debt, further increased by additional electricity theft when not enough wealth is generated to offset the fuel prices. A lack of funds can cause a downward spiral in the electric sector. This affects the maintenance, development, and expansion of the power sector. Most bodies work autonomously and use their profits generated by selling electricity to offset prices and pay tariffs on the transmission line to the GENCO (Generation Company) and DISCO (Distribution Company). Corruption is also a major reason for electricity theft; Pakistan is a very politically unstable country, and people have tried to exploit the system to get ahead. In 1998, the government cracked down on electricity theft and found that all accomplices were affiliated with political parties or were officials in charge of the energy sector in some capacity.

Some countries have accepted a certain amount of line losses and theft as necessary losses, ranging from 1% to 15% [

8]. Pakistan is no different in this regard having line losses and theft of about 19% in 2015, while the previous average was 13.5%, which is proof of the degrading energy infrastructure [

9].

2. Literature Review

Several case studies exist covering energy theft; these studies include countries such as Russia, India, the U.S.A., and the U.K. [

5,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. One of the most prevalent causes of theft can be affiliated with sociopolitical reasons. In previous papers, many different techniques and methods to prevent electricity theft have also been proposed, varying from regions in Africa to urbanized and rural Europe [

10]. So primarily, the literature is focused on two different aspects: firstly, the analysis of why it’s occurring, its economic, political and social impacts, and secondly, the different and innovative ways to mitigate theft through either technology or policy changes.

A case study was conducted in Pakistan; this empirical study gathered data from nine electricity distribution companies (DISCOS) over 22 years [

11]. This study’s main focus was analyzing the data using old and obsolete standards, such as LSDV (least squares dummy variable) and G.M.M. (generalized method of moments). This study also covers and overlaps with our study of PESCO (Peshawar Electric Supply Company, Punjab, Pakistan). Though this study only focused on the billing gathered from the distribution companies, the line losses were assumed to be electricity theft. One of the main key facts highlighted in this study was that sociopolitical impacts were a significant cause of electricity theft. The distribution companies in Pakistan are government-owned monopolies. The lack of policy-making, failure in governance, and the lack of competitive rivals have led to the organization’s decline. Things have gotten so bad that they cannot charge people for their commodity and have failed to prevent people from stealing it [

15].

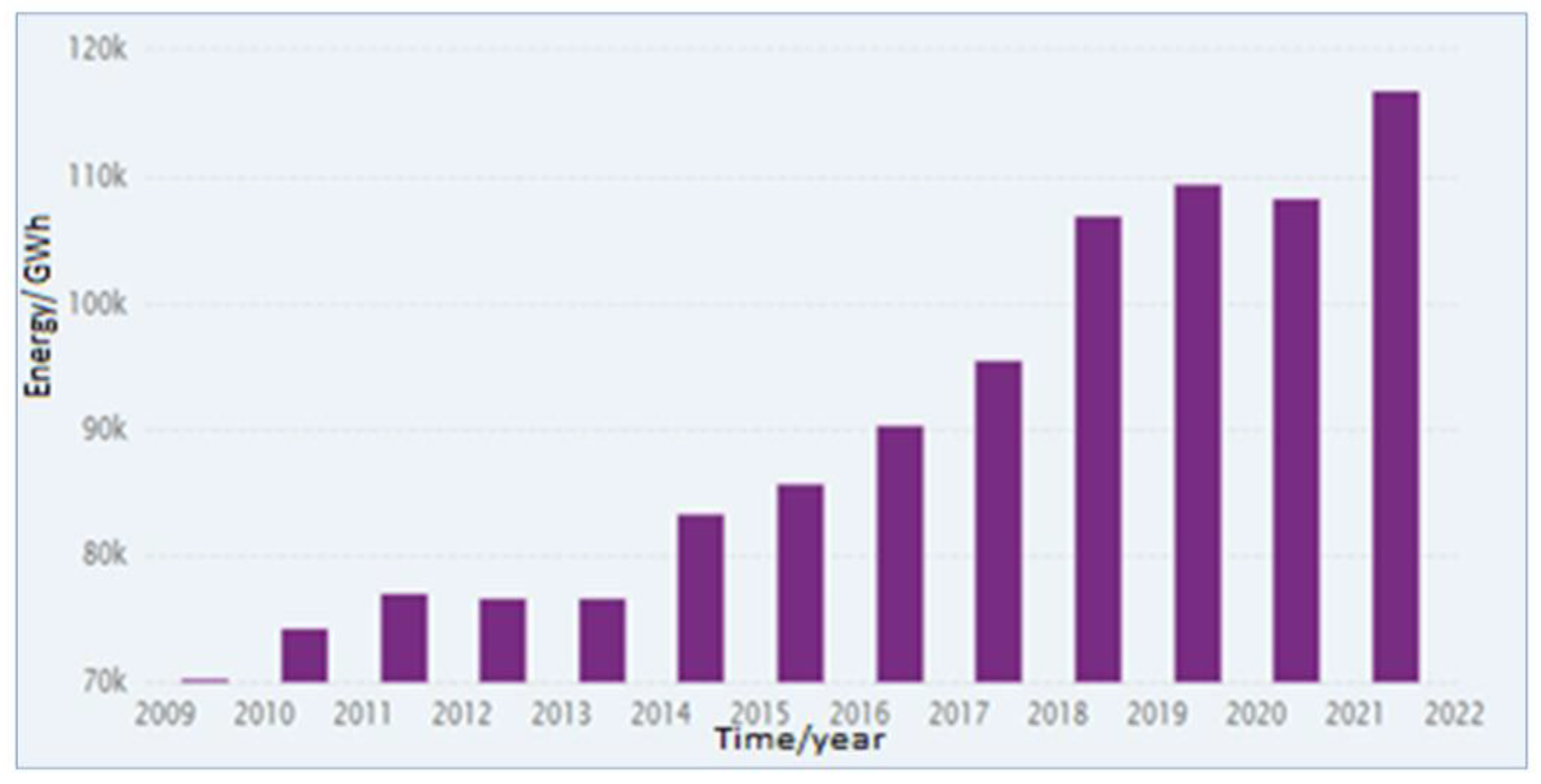

The government’s consistently poor policies, lack of action, and political instability, have further caused an increase in electricity theft. In 2010 when the study was concluded, Pakistan’s energy consumption was approximately 75 GWh, which is also validated by

Figure 1 [

16].

This almost doubled in the following 10 years, reaching 120 GWh. Although electricity production has increased, so has its theft. The losses faced by the government are greater than ever before. Previously, PESCO had a billing rate of 79%; in 2021, the rate was 64.8% [

18].

Thus, the sociopolitical environment of Pakistan has worsened in the last ten years of electricity theft and management. Although electricity generation is no longer an issue for this country, it still faces numerous power outages due to a lack of payments to private electricity generation companies, a weak distribution system, and a shortage of water and oil [

19].

South Africa is a county riddled with many complex problems, an incompetent government, and a legislative system. In many countries, electricity theft is known as an offense, but it is yet to be confirmed in South Africa. The legislative body is not unified on this matter. Thus from this example, you can understand how problematic it can be for generation and distribution companies to run, let alone make a profit [

20]. One primary reason that this previous study identified was the lack of monetary funds. This is one of the main reasons for blackouts in this country.

The other main reason, as mentioned above, is the legislative weaknesses; although a law exists to prevent electricity theft, they have not clearly defined what constitutes electricity theft; thus, people use its vague definition to try and circumvent the law. In this case, many people use fraud and meter tampering to commit electricity theft and evade the jurisdiction of this law.

The third main factor identified in this study was that the need for a smart grid system to monitor electricity theft would require a lot of capital and investment, both lacking by the government and the power sector. The possible improvements implemented as a result of this study or proposed include setting up autonomous energy generation units, usually solar-based power units, which provide electricity to an entire household and excess energy to the generation company. Other techniques include improving the legislation law and completing it by giving a list of ways electricity can and is stolen, with room to add new techniques if required [

12]. The final improvement involves society’s education and social education on how theft can bring about the collapse of nations. Only by working together in harmony and unity can we prosper as a nation.

Machine learning algorithms are one of the most advanced and complex computational logics implemented to this date. They require training the machine with large quantities of input data. This is used to develop the initial parameters for logic execution. The logic is then refined, and flaws are removed with testing. This method is not foolproof and has 75–99% accuracy. It all depends on the initial data set provided for training and testing [

21,

22,

23]. Many machine learning applications exist, from number plate identification and facial recognition to electricity theft. The most common technique used for ML (machine learning) in recent literature is the supervised algorithm and neural networks. In total, there are eight machine-learning techniques:

Reinforcement learning [

27].

Instance-based learning [

31].

The supervised learning method is where logical, labeled data is used to train the algorithm, and where input and outputs are defined, and the program must learn to recognize these parameters. Thus, the primary purpose is to classify data and give the required response in the form of identification. The same logic had inspired us to develop a supervised ML topology for our smart meter. Still, this was not an official part of the case study due to a lack of amenities and limited infrastructure.

The neural network method is the second most common method and one of the most complex. It is primarily used with the cloud [

32], as the cloud provides the hardware and processing power for executing the topology. It is a multivariable topology able to take into account many variables as it assigns weightage to every aspect and calculates the probability and likely hood of the occurrence of an event. Neural networks are used in smart grids and can be used to revolutionize the energy sector as a whole [

33]. It can consider energy input, output, theft, theft location, loss, and power quality parameters. It can autonomously manage the grid, power regulation, and billing if done properly. Thus, machine learning plays an integral part in the energy sector [

34], unifying it all together into one system that manages and controls all aspects in coordination, the smart grid. Its application has been developed and tested on the micro grid level as proof of concepts.

The work highlights the impact of modernization. The results are evident by the energy consumption before this study and after its completion. Pakistan’s energy grid has been steadily upgraded by implementing new policies. The replacement of analog with digital electric meters was a point of focus. The next step involved the testing and evaluation of smart meter technology on the electric grid. This is where our study has identified a major gap. There exists no case studies regarding electricity theft in Pakistan after the change from analog to digital meters. The last study was a decade old and for a country suffering with the problem of electricity theft; we conducted our research based on the pervious finding to see how the energy sector had evolved. We compared studies of electric grids that were conducted in developing countries, and we used the ideas from developed countries to set the bases from further features in out prototype. We introduced dynamic energy calculation, set the basis for neural network integration, and decentralized bilateral trade between consumers and suppliers. The main focus is on energy theft and how smart meters can detect the localized area in which it occurs.

4. Results and Discussion

The data below was extracted from the 2-month survey, which shows the reading of the selected major energy-consuming sectors. To add variation, several different types of power consumers were observed, and discrepancies were observed in half the commercial sectors, one-fourth of the industrial producers, and only one of the ten observed residential sectors.

The 2-months data was used to identify electricity theft in the area, and several meters linked under this primary sector smart meter were checked and evaluated for tampering. Seventy-two illegal connections were identified in this case study, of which 58 were rurally located in the rural industrial sector. Twelve were commercial, and two were placed in residential areas as tampered or faulty meters. The margin of error settings for this study was 10% due to the difficulty of installation of smart meters and of the further distribution line to provide power to the locality. The power-supplying organization does not charge for line losses, so the discrepancies under 10% are identified as valid line losses. However, further machine learning analysis could reduce this margin of error by close to 5%.

This case studies identified that the majority of electricity theft occurred in less populated areas where the population density was less than 200 people/. The lack of a densely populated society provides ample opportunity for people to tamper with their meter, and many businesses are tempted to take part in nefarious and illegal means to turn a profit.

In this study, a total area of 15 km

2 was covered, and we could monitor 2 hospitals, 2 universities, 4 industrial companies with an industrial connection, 30 shops, and 2800 houses. This only comprised 10% of the load of consumers in this area, but the results were similar to previous studies. The probabilistic analysis showed that the education sector, which is mainly privatized, is responsible for almost 1–2% of the electricity stolen, the hospital and other essential service facilities, which are usually always government-owned, are responsible for 3–11% of electricity theft, homes and the domestic sector accounts for 11–21%, the commercial sector for 17–35%, and the industrial is responsible for the most theft, 30–48%. All this information can be extrapolated from

Table 4.

This data can be further divided to provide a more concise and precise description of the experimental results and their interpretation, and to allow practical experimental conclusions to be drawn.

Figure 7 displays the information for

Table 4 in a more presentable manner.

In

Figure 7, This study primarily focused on electricity theft, but we were also able to identify many factors related to power quality; as such, the power factor (PF) of the hospital and industries varied quite a bit, ranging from 0.5 to 0.7. These dips in PF were probably due to the use of reactive power-intensive machinery, for example, M.R.I. machines in hospitals and motors in industrial manufacturing. Although this data was irrelevant to electricity theft, it can greatly help improve the power quality index and reduce excess electricity consumption due to reactive power losses.

In

Figure 8, shows that the electricity theft detected in this case study is only a fraction of the average theft. The site selected for this study was carefully identified as a planned, managed, and maintained city sector. The total energy theft for this study is assumed to be 100%. From this, most of the power stolen (94%) accounted for only 1% of the total energy consumption that could not be accounted for; the most likely explanation is due to grid degradation. Due to this, we set a base of 5% on average energy loss. The total energy unaccounted for was less than 8000 units of power for the two-month study, and produced for these two months was approximately 280,000 kWh. This amounted to about 2% of the total energy, which is close to the acceptable limit for energy theft. Although a total of 2% of energy was lost, we were able to help identify sources of theft for 20% of the energy being stolen from the area through data analysis. After electricity theft, users were identified and connections removed; the estimated theft is nearly 1.6% of the total supply.

4.1. Techniques for Theft Detection

Many techniques are used for electricity theft; the most common and prominent of these are mentioned below. The category of electricity theft falls into two categories: meter tampering and line tampering [

38]. Meter tampering includes reversing the meter counter, using magnates, rotating the meter, and neutral removal and grounding. The main technique employed for line tampering is known as the direct hook technique (or Kunda) [

9,

38].

4.2. Direct Hook Technique

In

Figure 9, Approximately 80% of all electricity theft is energy that is directly and illegally stolen from the power line, either through the use of a wire or bypassing the meter. This energy consumption is recorded on the back end, but no meters are present or bypassed; thus, no bill is generated. This image depicts electricity theft using the Kunda system [

39].

4.3. Meter Tampering

Most meters installed in commercial and residential areas are old and mechanical. They have a metal disc that rotates and counts the units and the electricity used. Although many of the new electric meters that are installed are digital, and most of the below-mentioned techniques are still applicable in more complex ways, digitization has made electricity theft harder. This technique involves cracking and opening the plastic shell of the mechanical/digital meter. The digital meters have an inherent resistor, which is used to calculate the power consumption and increase the digital count; tampering with this resistor makes the meter go slower or faster. Similarly, the mechanical meter can be tampered with by attaching magnets to slow the spinning dial and reduce the speed at which the meter counts units of power consumed, or to manually roll the mechanical dials backward to lower the unit count [

10].

In

Figure 10, Other ways include swapping the input (live or R.E.D.) wire with the black (neutral) in the meter but not connecting the neutral wire and just letting it stick in the meter, generating the illusion of a connected meter while using ground or earthing to complete the circuit. In this way power does not flow through the resister or mechanical load in the meter, thus not increasing the energy consumption count. Thus the main point of interest for tampering is the resistor or the spinning mechanical disk, and the only protection they have are the factory-manufactured seals installed to stop tampering. These seals are the only visible indicator of tampering or having the meter sent back to the manufacturers for testing.

4.4. Smart Meter Features and Advantages

The proposed smart meter design is much more refined than the basic digital meters used by the Pakistan government and its institutes. The only improvement from the previous design is the removal of mechanical components, resulting in increased accuracy and precision. The net metering meters are similar in design but have the additional ability to deliver power to the grid [

41].

Our designed meter is a smart meter based on the IEEE definition [

42]; it time stamps data calculated at every instance and sends it to a unified database through serial communication from an Arduino pin; it can even use demand side management measures, such as load curtailing, given you have such appliances that are compatible. This removes the data storage problem and ensures dynamic, consistent, reliable data. As mentioned above, the code within a microcontroller is used to calculate all the data parameters. These include voltage, current, the phase between voltage and current, power consumption, total power consumed, power quality index, and instantaneous energy cost.

Although power markets do not exist at a domestic level, we planned for this and incorporated the ability to be charged for electricity dynamically, not just at a fixed rate. This is important for the further development and privatization of the energy sector. Pakistan’s energy sector was welfare-based, and instead of focusing on having a strong economic model and securing profits, it was heavily subsidized. The future of energy infrastructure can only exist with competition, not a centralized government-run monopoly. Thus we added this feature to accommodate future energy suppliers [

43].

This presence of dynamic billing will help regulate the energy sector and help identify key weaknesses. The varying energy cost will help mitigate high consumption when energy demand approaches peak load, as generation plants would be working on lower efficiency because they would be pushing past their optimal energy generation and approaching max era [

44]. This energy generation is more expensive and thus would pass the extra bill to the consumers. Those who can afford it will continue using energy, and those who prefer not to will suffer extra charges that will reduce their energy load.

The smart meter is connected to a serial communication port used to communicate data; this includes electricity prices and the different suppliers of electricity (for this case study there is only PESCO, though the ability to add and integrate other energy providers is present). The intelligent meter calculation of power can easily detect unpredictable power consumption; this includes both power injection and theft. If the average power consumption of a residential house is 30 kWh and yours is 5 kWh, and there is an increased line loss, then your meter will be highlighted for inspection. This is possible because of an interconnected data storage and evaluation database. This data generated from the smart meters can help manage the energy infrastructure by predicting trends and identifying suspicious users.

Combined with a central computation server, these smart meters can calculate power consumption and utilization perfectly. The system can identify if the extra load has been added illegally (Kunda) resulting in electricity theft, and can pinpoint the approximated area of interest on the distribution line. This is, in effect, due to changes in energy/current flow and grid resistance.

The smart meter infrastructure can be fully automated and be independent of human interference. The billing is digital and without the need for a meter reading. It can identify power consumption trends and help the generation companies ramp up and down energy production before it can approach the available limit or cause excess production and frequency imbalance. They are compatible with the internet. Our current model uses serial communication. However, the Arduino controllers come with an Ethernet port that allow for remote monitoring for the user, not just the distribution provider in charge of billing. This Ethernet interface can push an IoT revolution and make accessibility of billing data from your home (and when you are away on a trip) much more accessible [

45]. You can also link electrical appliances to automatically turn them on and off remotely. This further pushes IoT integration into the energy sector. This extra accessibility is a great quality-of-life feature.

4.5. Theoretical Analysis

The possible theoretical analysis is based on previous case studies in relevant areas, including India, Pakistan, and South Africa. The previous literature shows that electricity theft is very high. Theoretically, we were able to identify all regional power supply companies and chose one of them with a high electricity theft ratio that was quickly accessible and willing to corporate with us in this case study. Thus PESCO was chosen. Choosing a developing area where the grid was newly founded was easier. We would expect fewer loads here and less theft; thus, the 38% for

Table 1 was expected to reach a value of 8–13%. The reasons for this were:

New regional area being developed (less than 50 years old).

High property and rental prices.

Developing area.

Unoccupied land (unbuilt houses).

Security and area management committee.

Amenities present in most of the area.

Most urban areas lack two or more of these theft-mitigating reasons. Lower-end portions of an urbanized site are considered slums with reduced amenities and no executive managerial committee. The theoretical aspect of why electricity theft has occurred has been briefly discussed in mentioned papers and articles; they have to do with politics, social engineering, corruption, the economy, etc. [

18,

46,

47].

4.6. Possible Improvements (Neural Networks)

In

Figure 11, shows that, the presence and possibility of neural networks in the smart grid has always been proposed, and the way of introducing them has been discussed in recent literature [

48,

49,

50]. All neural networks have the following basic design:

In our current data analysis, we had a margin of error of 10% when calculating the probability of theft. This is still a tiny margin of error, but it can be reduced using neural network architecture, such as ANN and CNN. In previous literature, an error of only 3% has been shown using neural networks. The data generated from the unfed meters in the entire smart meter grid provide an enormous amount of data, which leads to the deployment of the field of big data. Cloud computing and 5G infrastructure have made the processing and execution of neural network topologies affordable.

Neural networks can include the time series RNN model [

51]. This model relies on a fully connected neural network (FCNN) and RNN model to solve problems and, in our case, predict data and trends for the data [

52]. It utilizes a data-driven analytical model to predict the exact value of the points, and not just the movement and direction of propagation, with an accuracy of 98% [

53]. Even with the existing data gathered and stored in the offices of PESCO, we have enough data to identify discrepancies in billing, as some people only steal electricity in hot months to reduce their electric bill and save money. This is in clear opposition to the general data trend and can be easily identified.

The standalone model that we currently have uses supervised machine learning techniques with a logic diagram (shown in

Figure 12) depicting its simplified tree diagram. The potential of this system, if used as an innovative grid network, can employ the neural network topology to work as a unified system instead of several autonomous individual systems working in coordination. The difference is that there is a latency delay of 5–30 s between data; in the unified neural network model, the processing delay and analysis being performed on the cloud saves a lot of time, reducing the efficient communication time down to 0.2 s, and can dynamically identify the location and line of theft to an estimated area of 20 m.

Discussions of the results and how they can be interpreted from the perspective of previous studies and the working hypotheses, along with their findings and their implications, should be discussed in the broadest context possible. Future research directions may also be highlighted.

4.7. Block Diagram

Figure 12 finds the bases for the smart meter theft detection system. Suppose the cumulative power consumption is within the 10% error margin. In that case, the system continues to run. Still, if the instantaneous energy consumption exceeds the billing being recorded, a system diagnostic is run to evaluate where the power is lost and identify the expected power lost. This calculation adds to the fine awarded to the people responsible for taking part in this theft.

The algorithm is individually run on the Arduino R3 microcontroller, and the main theft detection algorithm is run on the centrally connected processing unit, which has been gathering data from the smart meters. The evaluation of this data is currently a simple program, but ANN and other neural network-based codes can greatly improve the efficiency, though that would exceed the scope of this work, for our central processing unit cloud server (AWS) [

54].

The training was done using data set from a previously published paper [

33,

54]. The model was based on the chines data set used for this paper using 2-D electricity consumption data; the parameters were electricity voltage, current, and phase from all of the measurement points. The data was then fed into a 6-layer neural network with four hidden layers. This classified it to be a deep neural network. Other parameters were kept similar to the previous study in China; CNN was used with 2-D electricity consumption as input data. The training of the model data only included one year of electricity consumption from January 2015–2016 with test data from local electricity theft patterns. The model was weight training that accurately identified 93% percent of theft with the training and testing data provided. This was not practically applied due to the lack of funds and amenities needed in the developing city when this study was conducted.

4.8. Analysis and Motivation

This study also implements a potential test case meter info-structure that could be used to design future meters, providing many features have futuristic potential. The components of dynamic response were successfully tested and executed, such as dynamic billing and tampering detection with both the meter and neural network models. The scope of this study has shown that people are willing to accept modernization, and it can improve how we carry out tasks, such as billing and theft detection. The path we have studied has proven that this meter design can be used to privatize the energy monopoly and turn it into a competitive environment for customer care, economic profit, and prosperity, and that it also potentially allows the user to switch over to another electricity provider at a moment’s notice and be only charged for their electricity cost.

5. Conclusions

The case study was only able to be conducted with the approval of PESCO and in an organized and planned area of development. Pakistan suffers from unstructured growth and urbanization. This leads to the addition of an unpredictable load on the existing power system. Thus, the only planned area in the second most inefficient distribution provider (PESCO) was Hayatabad.

The study concluded that the most likely area of theft was the rural area or area involved in industrial development. After the rural areas, the commercial districts and domestic districts were the second most common place for electricity theft. Almost no electricity theft was identified in universities and hospitals. This is following previous literature, where in developing countries, it has been identified that the most common form of electricity being stolen is tampering with the power line. This was obvious in the commercial district results, where a total of 45–60% of all power is stolen at the local level, or places where voltage can be directly used (220 V) [

54]. This leaves the remaining 40% of power, which is either lost in line losses or stolen from the high voltage distribution level, to be at the industrial level, which typically is at 11 kV, and our study found conclusive evidence of this.

The primary data gathered in this study analyzed power consumption and its theft. The analysis can be summed up from

Figure 9 and

Figure 10. They both show the total energy theft and the comparison of robbery to the legitimate users.

Table 4 shows the results of the study. Over two months, the results were verified and consolidated into

Table 4 to present a more precise and more concise picture. The data was modified to adjust for load shedding and line losses. However, losses caused due by PF fluctuation were not adjusted, as they are the consumer’s responsibility, and they are justly billed for it. A non-ideal PF causes losses in the form of electric and magnetic fields. These are minute and insignificant on the domestic side, but in commercial and industrial sectors, they can cause a significant increase in billing if not properly maintained. The only energy theft detected in hospitals and universities can be attributed to the non-ideal nature of PF. The residential, commercial, and industrial sectors have significant portions of energy theft. In the case of residential districts, some were actively stealing energy, while a portion of it was due to the PF, fluctuation due to the presence of UPS and the induction motors for water pumps. When analyzing the commercial district, this was the most significant energy theft and revenue loss source. Most people employed the Kunda technique according to the data that was analyzed and reported. These people were prosecuted under the law. It is here that our study helped improve the situation of energy theft. Saving more than 500,000 Rs per month by identifying the shortcoming.

The PF information can be used to improve the grid infrastructure, as overloaded lines have higher line losses. In our case study, several power lines are overloaded as no theft is suspected, but consistent losses are reported. The industrial sector’s data management has shown that many energy-intensive industries work during the night at optimal efficiency when load demand is low.

This work’s novelty lies in the fact that it studies and improves the condition of electricity theft in Pakistan, while comparing the results of studies performed in other developing countries and quantitatively showing how electricity theft was reduced by analyzing the data from intelligent meters when compared to simple digital or analog ones.

But, it can also be added to the manuscript if the discussion is unusually long or complex.