Vulnerability to Poverty in Chinese Households with Elderly Members: 2013–2018

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Discussion about Pension Reform in China

2.2. Discussion about Reform of Medical Insurance Scheme in China

2.3. Discussion about the Impact of Welfare Schemes on Household Consumption

2.4. Discussion about the Impact of Development Capacities on the Household Vulnerability

3. Data Description

4. Theoretical Framework

5. Methodology

5.1. Feasible Generalized Least Squares

5.2. Difference-in-Difference (DID) and Propensity Score Matching (PSM)

- (1)

- We estimated the propensity score, which is the vulnerability rate of the head of household with government institutional pension before 2015, and it was estimated by the Logit regression; two samples with the same propensity score were matched and, depending on whether they participated in the 2015 pension reform, they were divided into two groups, treatment group and control group.

- (2)

- Secondly, after the samples of the experimental and control groups were matched and propensity scores were assessed, a proper matching algorithm was selected. The conventional algorithm of k-nearest neighbour matching relies heavily on the number of matched k samples, and when k = 1, the close propensity scores from the control group may not be the best choice due to the large variance. When choosing the algorithm of radius matching, it was not easy in this study to find a correct radius with all the samples with close propensity scores within the radius. Thus, the kernel matching algorithm was adopted, which is a universal matching approach that matches all the individuals in treatment and control groups separately.

- (3)

- The average treatment effect for the individual in the treatment group was calculated.

- (4)

- Then, the average treatment effect for the individual in the control group was calculated.

- (5)

- The estimation of the average treatment effect of the treated groups can be written as follows:

5.3. Multidimensional Vulnerability Analysis

6. Results and Analysis

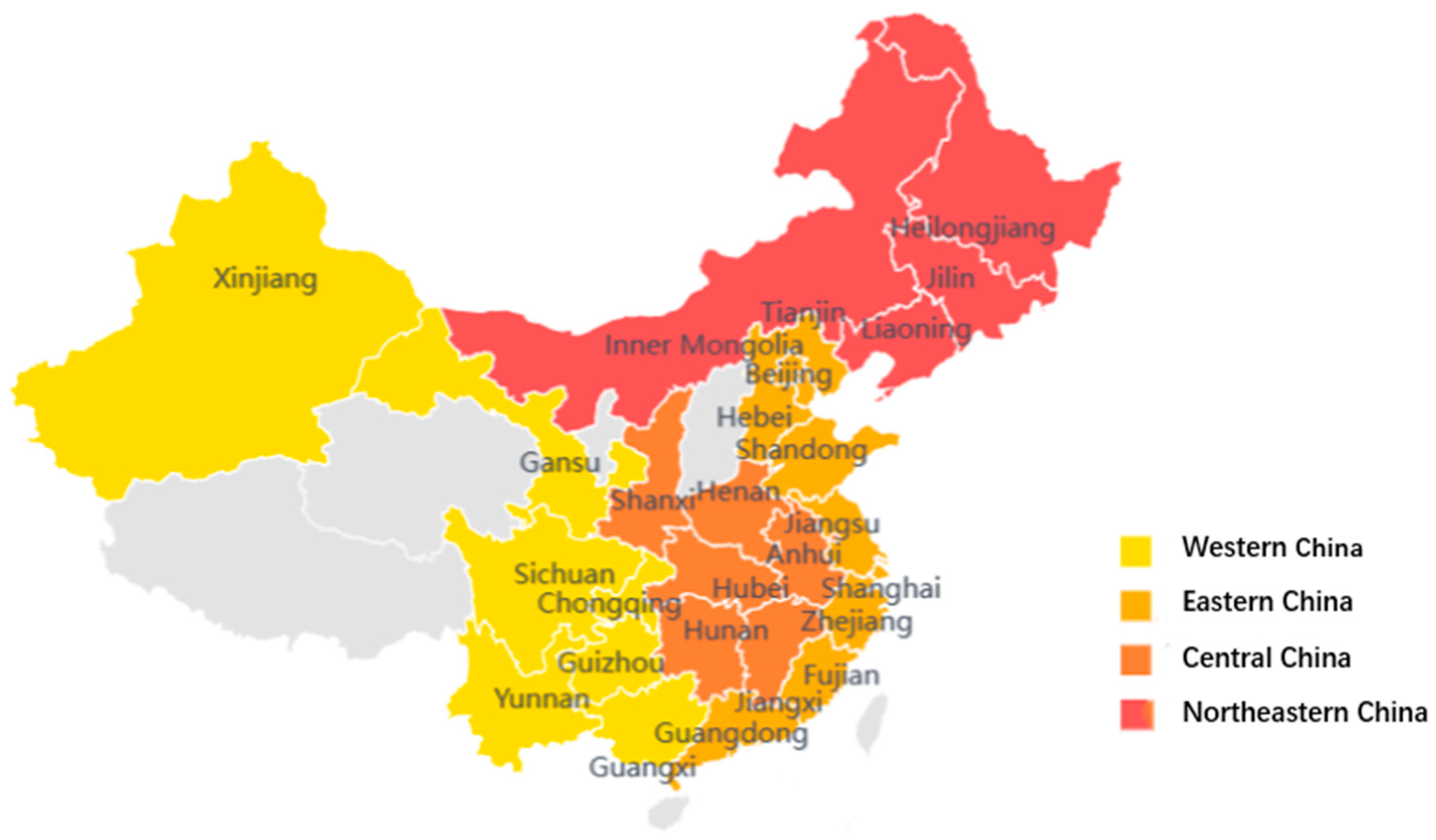

6.1. The Intra-Regional Differences of Vulnerability Rates in Chinese Household

6.2. The Development Capabilities That Contribute to Household Vulnerability

6.3. Results and Discussions about DID and PSM

6.4. Results and Discussions about Multidimensional Vulnerability Analysis

7. Conclusions

8. Limitation and Further Study

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Name of Pension | Target | Contents |

| Universal Pensions | ||

| Rural Residents’ Pension (RRP) [12] |

|

|

| Urban Residents’ Pension (URP) [11] |

|

|

| Job-Related Pensions | ||

| Government and Institutions Pension (GIP) [86] |

|

|

| Enterprise Employee Pension (EEP) [12] |

|

|

| Private Pensions | ||

| Commercial Pension [87] |

|

|

| Life Pension [87] |

|

|

| Other Pensions | ||

| Old Age Pension Allowance [11] |

|

|

| Name of Medical Insurance | Target | Contents | Additional Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urban Employee Medical Insurance [88] | All urban employees with a long contract. |

|

|

| Urban Resident Medical Insurance [89] | Urban residents without Urban Employee Medical Insurance. |

|

|

| New Cooperative Rural Medical Insurance [90] | All rural residents are eligible for the programme. |

|

|

| Commercial medical insurance | Insured people from the insurance company. |

|

| Characteristics | First Model | Second Model | Third Model | Fourth Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate of coverage | 65.2% | 6.70% | 11.17% | 16.87% |

| Whether a medical savings account is available | Yes | No | No | No |

| Inpatient services | Yes | Yes | Only reimburse for catastrophic diseases. | Yes |

| Outpatient services | Yes | No | Only for catastrophic diseases. | No |

| Extra benefits | There is a deductible and a reimbursement cap for using a medical savings account. | There is a free physical check-up each year for who has not used any medical services that require reimbursement in NCMS. | No | No |

References

- Zeng, Y.; George, L.K. Population aging and old-age care in China. In Sage Handbook of Social Gerontology; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010; pp. 420–429. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Y. Toward deeper research and better policy for healthy aging—Using the unique data of Chinese longitudinal healthy longevity survey. China Econ. J. 2012, 5, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fang, E.F.; Scheibye-Knudsen, M.; Jahn, H.J.; Li, J.; Ling, L.; Guo, H.; Zhu, X.; Preedy, V.; Lu, H.; Bohr, V.A.; et al. A research agenda for aging in China in the 21st century. Ageing Res. Rev. 2015, 24, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bai, X. Images of Ageing in Society: A Literature Review. J. Popul. Ageing 2014, 7, 231–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, N.; Bai, X. Modernization and its impact on Chinese older people’s perception of their own image and status. Int. Soc. Work. 2011, 54, 800–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Gao, S.Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y.C.; Rosenberg, M. Understanding the spatial disparities and vulnerability of population aging in China. Asia Pac. Policy Stud. 2019, 6, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, T.; Yang, P. Finding the vulnerable among China’s elderly: Identifying measures for effective policy targeting. J. Aging Soc. Policy 2018, 31, 271–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Sun, X.; Huang, L. Chronic disease and medical spending of Chinese elderly in rural region. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2021, 33, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Xu, J.; Zhang, X. The role of housing wealth, financial wealth, and social welfare in elderly households’ consumption behaviors in China. Cities 2020, 96, 102437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, S.; Sen, A. Human Development and Economic Sustainability. World Dev. 2000, 28, 2029–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Whiteford, P. From enterprise protection to social protection: Pension reform in China. Glob. Soc. Policy 2003, 3, 45–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Walker, A. Pension system reform in China: Who gets what pensions? Soc. Policy Adm. 2018, 52, 1410–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sun, Z.; Liu, H.; Liu, Z.; Xiong, W.; Zhong, R. Research on intellectual precision poverty alleviation and rural revitalization strategy of Enshi prefecture in Wuling Mountain area based on agricultural intellectual property rights protection and intellectual resources exploitation. Acta Agric. Jiangxi 2018, 30, 135–141. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Q.; Mi, H. Evaluation on the Sustainability of Urban Public Pension System in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, S.; Yang, L.; Zhang, T. International comparison of the pension replacement rate and the pension reform in China. Zhejiang Acad. J. 2012, 4, 170–199. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health; Ministry of Finance & Affairs. Announcement of the Development of New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme in 2012; China Government: Beijing, China, 2012.

- Qin, L.-J.; Chen, C.-P.; Li, Y.-H.; Sun, Y.-M.; Chen, H. The impact of the New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme on the “health poverty alleviation” of rural households in China. J. Integr. Agric. 2021, 20, 1068–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X.; Lin, W. The New Cooperative Medical Scheme in rural China: Does more coverage mean more service and better health? Health Econ. 2009, 18, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, L.; Zhang, W. The Development on China’ Health, No. 3.; Social Science Academic Press: Beijing, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. The Progress of the New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme (NRCMS) in 2013 and Major Tasks in 2014; National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2014.

- Yip, W.; Hsiao, W.C. The Chinese Health System At A Crossroads. Health Aff. 2008, 27, 460–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagstaff, A.; Lindelow, M.; Gao, J.; Xu, L.; Qian, J. Extending health insurance to the rural population: An impact evaluation of China’s new cooperative medical scheme. J. Health Econ. 2009, 28, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, C.; Pan, J. The effect of the health poverty alleviation project on financial risk protection for rural residents: Evidence from Chishui City, China. Int. J. Equity Health 2019, 18, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Holzman, R.; Hinz, R. Old-Age Income Support in the 21st Century: An International Perspective on Pension Systems and Reform; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; pp. 55–57. [Google Scholar]

- Leimer, D.R.; Lesnoy, S.D. Social Security and Private Saving: New Time-Series Evidence. J. Politi- Econ. 1982, 90, 606–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldstein, M. Social security and saving: New time series evidence. Natl. Tax J. 1996, 49, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.L.; Liu, C.; Guan, X.P.; Mor, V. China’s Rapidly Aging Population Creates Policy Challenges In Shaping A Viable Long-Term Care System. Health Aff. 2012, 31, 2764–2773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, J. Effects of Social Security Wealth on the Consumption of Chinese Urban Households. J. Shandong Univ. 2008, 3, 105–112. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y.; Wang, M. The Effect of PAYG Pension Insurance on Savings. J. Quant. Tech. Econ. 2010, 3, 96–106. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yue, A.; Yang, C.; Chang, F.; Tian, X.; Shi, Y.; Luo, R.; Yi, H. Effects of New Rural Old-Age Social Insurance on Households’ Daily Expenditure. Manag. World. 2013, 8, 101–108. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Su, C.; Li, X. The Impact of Social Security on Urban Residents’ Consumption: A Case of Shandong Province. J. Shandong Univ. 2012, 6, 81–86. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, C.C.; Lugauer, S. Demographics and Aggregate Household Saving in Japan, China and India; NBER Working Paper No. 21555; NBER: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lugauer, S.; Mark, N.C. The Role of Household Saving in the Economic Rise of China; HKIMR Working Paper No. 04/2013; HKIMR: Hong Kong, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sung, K. An Asian perspective on aging east and west: Filial piety and changing families. In Aging in East and West: Families, States, and the Elderly; Bengtson, V., Kim, K., Myers, G., Eun, K., Eds.; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Gubhaju, B.B.; Moriki-Durand, Y. Below-replacement fertility in east and southeast asia: Consequences and policy responses. J. Popul. Res. 2003, 20, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y. As Good as a Boy” But Still a Girl: Gender Equity Within the Context of China’s One-Child Policy. SAGE Open 2022, 12, 21582440221082097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Fan, J.; Liang, B.; Zhang, L. Evaluation of Sustainable Livelihoods in the Context of Disaster Vulnerability: A Case Study of Shenzha County in Tibet, China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, Z.; Wu, X. Social Policy and Political Trust: Evidence from the New Rural Pension Scheme in China. China Q. 2018, 235, 644–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Xin, L.; Zhang, J. Does the New Rural Pension System Promote Farmland Transfer in the Context of Aging in Rural China: Evidence from the CHARLS. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zeng, Y.; Luo, J.; Ou, L.; Yuan, M.; Zhou, Z.; Han, Y.; Fang, Y. The impact of medical insurance on medical expenses for older Chinese: Evidence from the national baseline survey of CLHLS. Medicine 2019, 98, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, C.; Cao, M.; Yang, T.; Ma, L.; Wu, M.; Cheng, L.; Ye, R. Inequalities in the commuting burden: Institutional constraints and job-housing relationships in Tianjin, China. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2022, 42, 100545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreger, C.; Zhang, Y. Is there a bubble in the Chinese housing market? Urban Policy Res. 2013, 31, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xiao, L.; Qiu, Q.; Gao, L. Chinese Housing Reform and Social Sustainability: Evidence from Post-Reform Home Ownership. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mou, Y.; He, Q.; Zhou, B. Detecting the Spatially Non-Stationary Relationships between Housing Price and Its Determinants in China: Guide for Housing Market Sustainability. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carlsson, F.; Martinsson, P.; Qin, P.; Sutter, M. Household Decision Making and the Influence of Spouses’ Income, Education, And Communist Party Membership: A field Experiment in Rural China. 2009. Available online: https://docs.iza.org/dp4139.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Zhou, W. Brothers, household financial markets and savings rate in China. J. Dev. Econ. 2014, 111, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Billari, F.C.; Gietel-Basten, S. Health of midlife and older adults in China: The role of regional economic development, inequality, and institutional setting. Int. J. Public Health 2017, 62, 857–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fang, H.; Feng, J. The Chinese Pension System (No. w25088); National Bureau of Economic Research: Beijing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Public Policy Research. Setting an Ideal Retirement Age! Available online: https://www.cppr.in/archives/setting-an-ideal-retirement-age (accessed on 7 April 2022).

- Imaidhuri, S.; Jalan, J.; Suryahadi, A. Assessing Household Vulnerability to Poverty from Cross-Sectional Data: A Methodology and Estimates from Indonesia; Columbia University: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ligon, E.; Schechter, L. Measuring vulnerability. Econ. J. 2003, 113, C95–C102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hua, X.; Yan, J.; Zhang, Y. Evaluating the role of livelihood assets in suitable livelihood strategies: Protocol for anti-poverty policy in the Eastern Tibetan Plateau, China. Ecol. Indic. 2017, 78, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Q.; Li, E.; Zhang, P. Livelihood sustainability and dynamic mechanisms of rural households out of poverty: An empirical analysis of Hua County, Henan Province, China. Habitat Int. 2020, 99, 102160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Xu, D.; Xie, F.; Liu, E.; Liu, S. The influence factors analysis of households’ poverty vulnerability in southwest ethnic areas of China based on the hierarchical linear model: A case study of Liangshan Yi autonomous prefecture. Appl. Geogr. 2016, 66, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. A Decade of Human Development. J. Hum. Dev. 2000, 1, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Y.; He, L. A note of academic history about accurate poverty alleviation: Sen’s poverty concept. Econ. Issue 2016, 12, 17–20. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, W.; Feng, Y. Impact of different models of rural land consolidation on rural household poverty vulnerability. Land Use Policy 2022, 114, 105963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amemiya, T. The Maximum Likelihood and the Nonlinear Three-Stage Least Squares Estimator in the General Nonlinear Simultaneous Equation Model. Econometrica 1977, 45, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooldridge, J.M. Introductory Econometrics: A Modern Approach, 6th ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bui, K.L.; Bui, T.H. Does Rural Credit Mediate Vulnerability Under Idiosyncratic and Covariate Shocks? Empirical Evidence from Vietnam Using a Multilevel Model. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2022, 34, 172–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, W.H. Econometric Analysis, 8th ed.; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Imai, K.S. Poverty, undernutrition and vulnerability in rural India: Role of rural public works and food for work programmes. Int. Rev. Appl. Econ. 2011, 25, 669–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.L.; Zhu, K.; Chen, Q.Y.; Li, J.; Cai, J.; He, T.; Liao, H.P. Impact of the COVID−19 Pandemic on Farm Households’ Vulnerability to Multidimensional Poverty in Rural China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Li, X.; Li, W. The Nexus between Credit Channels and Farm Household Vulnerability to Poverty: Evidence from Rural China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cisilino, F.; Bodini, A.; Zanoli, A. Rural development programs’ impact on environment: An ex-post evaluation of organic faming. Land Use Policy 2019, 85, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckman, J.J.; Ichimura, H.; Todd, P. Matching As An Econometric Evaluation Estimator. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1998, 65, 261–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkire, S.; Roche, J.M.; Ballon, P.; Foster, J.; Santos, M.E.; Seth, S. Multidimensional Poverty Measurement and Analysis; Oxford University Press: Cary, NC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Angelillo, N. Vulnerability to poverty in China: A subjective poverty line approach. J. Chin. Econ. Bus. Stud. 2014, 12, 315–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artha, D.R.P.; Dartanto, T. Multidimensional Approach to Poverty Measurement in Indonesia; LPEM-FEUI Working Paper No. 002; LPEM-FEUI: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, S.W.K.; Lo, I.P.Y.; Chau, R.C.M. Rethinking the residual policy response: Lessons from Hong Kong older women’s responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. Soc. Work. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Varis, O.; Yin, H. China’s water resources vulnerability: A spatio-temporal analysis during 2003–2013. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 2901–2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Peters, M. Chinese model of higher education. Encyclopedia of educational philosophy and theory. In Encyclopedia of Educational Philosophy and Theory; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D. Habitus, campus experience, and graduate employment: Personal advancement of middle-class students in China. J. Educ. Work. 2021, 34, 344–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, L. Self-employment of Chinese rural labor force: Subsistence or opportunity?—An empirical study based on nationally representative micro-survey data. J. Asian Econ. 2021, 77, 101–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Shen, J. Settlement intention of migrants in urban China: The effects of labor-market performance, employment status, and social integration. Appl. Geogr. 2022, 147, 102–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Huang, J.; Zhang, L.; Rozelle, S. The rise of migration and the fall of self-employment in rural China’s labor market. China Econ. Rev. 2011, 22, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhao, Q.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yu, X. Poverty and Subjective Poverty in Rural China. Soc. Indic. Res. 2020, 150, 219–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chinese National Statistics. China Statistical Yearbook 2021. 2021. Available online: http://www.stats.gov.cn/ (accessed on 27 February 2022).

- McDowell, L. Love, money, and gender divisions of labour: Some critical reflections on welfare-to-work policies in the UK. J. Econ. Geogr. 2015, 5, 365–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, R.; Liao, Y.; Xie, X.; Li, B.; Lin, X.; Liu, Q.; Liu, X.; Yu, W. Dynamic physical examination indicators of cardiovascular health: A single-center study in Shanghai, China. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0268358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, G.; Chen, H.; Xie, B.; Wang, M. Risk Assessment and Prediction of Air Pollution Disasters in Four Chinese Regions. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.; Alberini, A. Sensitivity of price elasticity of demand to aggregation, unobserved heterogeneity, price trends, and price endogeneity: Evidence from U.S. Data. Energy Policy 2016, 97, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luh, Y.-H.; Chang, Y.-C.; Ho, S.-T. Crop Switching and Farm Sustainability: Empirical Evidence from Multinomial Treatment-Effect Modeling. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, X.; Li, H.; Yao, P.; Liu, J.; Chen, F.; Sriboonchitta, S. Analysis of the Impact of Industrial Land Price Distortion on Overcapacity in the Textile Industry and Its Sustainability in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, P.R.; Rubin, D.B. Constructing a control group using multivariate matched sampling methods that incorporate the propensity score. Am. Stat. 1985, 39, 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, A. The Global Spread of Neoliberalism and China’s Pension Reform since 1978. J. World Hist. 2012, 23, 609–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Wang, F.; Sang, Q.; Wang, Q.; Gao, Y.; Huang, Y.; Yu, X.; Xiao, J.; Zhu, H.; Cui, C. Construction and Analysis of Actuarial Model of the Influence of Personal Tax Deferred Commercial Pension Insurance on Personal Pension Wealth in China. Mathematics 2020, 8, 2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F. Insurance coverage and agency problems in doctor prescriptions: Evidence from a field experiment in China. J. Dev. Econ. 2014, 106, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lu, J.; Hu, S.; Cheng, K.K.; De Maeseneer, J.; Meng, Q.; Mossialos, E.; Xu, D.R.; Yip, W.; Zhang, H.; et al. The primary health-care system in China. Lancet 2017, 390, 2584–2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Tsegai, D. The new cooperative medical scheme and its implications for access to health care and medical expenditure: Evidence from rural China. In ZEF Discussion Papers on Development Policy; Center for Development Research: Bonn, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 N = 1479 | 2015 N = 921 | 2018 N = 1099 | |

| Demographic characteristics | |||

| Females aged higher than 50 years old Or males aged higher than 55 years old | 88.44% | 90.23% | 94.27% |

| The number of elders in the household | |||

| 0 | 11.49% | 11.07% | 3.37% |

| 1 | 31.17% | 36.16% | 38.49% |

| 2 | 57.34% | 52.77% | 58.14% |

| Whether they belong to Chinese Communist Party | |||

| Yes | 11.83% | 17.05% | 15.01% |

| No | 88.17% | 82.95% | 84.99% |

| Whether they belong to an ethic minority | |||

| Yes | 7.44% | 6.41% | 7.83% |

| No | 92.56% | 93.59% | 92.17% |

| Whether they are married | |||

| Yes | 81.34% | 78.61% | 74.25% |

| No | 18.66% | 21.39% | 25.75% |

| Types of employment | |||

| Civil servant | 8.49% | 8.04% | 7.18% |

| Institutional employee | 7.16% | 8.58% | 7.55% |

| NGO employee | 5.07% | 5.50% | 5.45% |

| Enterprises’ employee | 35.65% | 39.12% | 35.82% |

| Self-employed | 14.94% | 15.97% | 23.82% |

| Farmer | 27.07% | 20.40% | 18.63% |

| Others | 1.62% | 2.39% | 1.55% |

| Types of pensions | |||

| Without pension | 24.07% | 28.12% | 30.60% |

| Government and institutional pension | 8.45% | 7.38% | 6.55% |

| Enterprise employee pension | 19.95% | 23.34% | 24.27% |

| Commercial pension | 0.68% | 0.76% | 0.55% |

| Life pension | 1.42% | 6.62% | 3.46% |

| Rural resident pension | 35.43% | 21.29% | 17.65% |

| Urban resident pension | 5.54% | 6.84% | 10.10% |

| Old age pension | 4.46% | 5.54% | 6.82% |

| ln (annual pension for last year) quartile | |||

| Quintile 1(4.09,2.48,4.61) | 1.51% | 8.03% | 3.64% |

| Quintile 2(4.61,4.61,9.39) | 6.68% | 10.00% | 28.59% |

| Quintile 3(9.29,9.92,10.23) | 74.24% | 65.47% | 54.29% |

| Quintile 4(10.23,10.23,12.26) | 18.32% | 16.50% | 13.48 |

| Regular physical examinations | |||

| Yes | 48.48% | 54.94% | 35.76% |

| No | 51.52% | 45.06% | 64.24% |

| Types of medical insurance | |||

| No medical insurance | 14.67% | 19.65% | 12.65% |

| Urban employee medical insurance | 36.03% | 35.50% | 36.77% |

| Urban residents’ medical insurance | 13.32% | 12.81% | 18.48% |

| New Rural Cooperative medical insurance | 30.44% | 28.01% | 26.57% |

| Private medical insurance | 5.54% | 4.02% | 5.55% |

| Household characteristics | |||

| Whether they take responsibility for caring for children | |||

| Yes | 60.78% | 61.02% | 59.87% |

| No | 39.22% | 38,98% | 40.13% |

| Whether they live with adult children | |||

| Yes | 65.99% | 72.53% | 62.42% |

| No | 34.01% | 27.47% | 37.58% |

| Whether they own property | |||

| Yes | 51.93% | 46.04% | 38.12% |

| No | 48.07% | 53.96% | 61.87% |

| ln (value of owned property) quartile | |||

| Quintile 1(0.26,0.41,0.41) | 1.42% | 1.63% | 2.72% |

| Quintile 2(0.69,0.69,1.39) | 59.91% | 63.08% | 46.86% |

| Quintile 3(2.30,3.00,3.40) | 9.67% | 28.35% | 21.02% |

| Quintile 4(3.00,3.69,6.70) | 29.00% | 6.94% | 29.40% |

| ln (total value of fixed assets) quartile | |||

| Quintile 1(4.61,3.91,4.61) | 2.37% | 2.71% | 3.18% |

| Quintile 2(7.60,8.99,9.23) | 45.77% | 47.77% | 46.86% |

| Quintile 3(9.90,10.86,11.00) | 27.05% | 24.32% | 25.11% |

| Quintile 4(10.63,11.66,12.18) | 24.81% | 25.20% | 24.85% |

| Variable | n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 N = 2700 | 2015 N = 4614 | 2018 N = 4437 | |

| Demographic characteristics | |||

| Females aged higher than 50 years old Or males aged higher than 55 years old | 90.96% | 90.98% | 92.40% |

| The number of elders in the household | |||

| 0 | 10.63% | 10.79% | 3.67% |

| 1 | 30.41% | 35.70% | 39.10% |

| 2 | 58.96% | 53.51% | 57.22% |

| Whether they belong to the Chinese Communist Party | |||

| Yes | 7.59% | 8.11% | 7.05% |

| No | 92.41% | 91.89% | 92.95% |

| Whether they belong to an ethic minority | |||

| Yes | 8.89% | 7.20% | 7.23% |

| No | 91.11% | 92.80% | 92.77% |

| Whether they are married | |||

| Yes | 79.56% | 78.39% | 72.26% |

| No | 20.44% | 21.61% | 27.74% |

| Types of employment | |||

| Civil servant | 0.26% | 0.63% | 0.65% |

| Institutional employee | 0.37% | 0.72% | 0.38% |

| NGO employee | 0.04% | 0.04% | 0.07% |

| Enterprises’ employee | 1.41% | 1.89% | 1.58% |

| Self-employed | 2.33% | 3.21% | 3.13% |

| Farmer | 63.56% | 56.05% | 54.97% |

| Others | 1.22% | 1.24% | 1.33% |

| Unemployed | 30.81% | 36.24% | 37.89% |

| Types of pensions | |||

| Without pension | 20.22% | 23.78% | 21.82% |

| Government and institutional pension | 1.74% | 1.26% | 0.43% |

| Enterprise employee pension | 1.74% | 3.01% | 0.02% |

| Commercial pension | 0.26% | 0.13% | 0.34% |

| Life pension | 0.30% | 1.41% | 0.65% |

| Rural resident pension | 67.89% | 60.38% | 61.48% |

| Urban resident pension | 2.56% | 3.88% | 14.24% |

| Old age pension | 5.30% | 6.16% | 1.01% |

| ln (annual pension for last year) quartile | |||

| Quartile 1(3.18,2.48,3.48) | 1.85% | 12.07% | 6.81% |

| Quartile 2(4.61,4.61,6.73) | 2.96% | 6.74% | 43.61% |

| Quartile 3(6.49,6.73,7.09) | 73.93% | 58.45% | 30.16% |

| Quartile 4(10.23,10.26,10.22) | 21.26% | 22.74% | 19.42% |

| Regular physical examinations | |||

| Yes | 36.56% | 38.19% | 30.27% |

| No | 63.44% | 61.81% | 69.73% |

| Types of medical insurance | |||

| No medical insurance | 4.74% | 19.18% | 4.06% |

| Urban employee medical insurance | 2.37% | 5.05% | 3.63% |

| Urban residents’ medical insurance | 3.85% | 2.45% | 13.50% |

| New Rural Cooperative medical insurance | 88.74% | 71.82% | 76.29% |

| Private medical insurance | 0.30% | 1.50% | 2.52% |

| Household characteristics | |||

| Whether they take responsibility for caring for children | |||

| Yes | 60.48% | 63.07% | 59.34% |

| No | 39.52% | 36.93% | 40.66% |

| Whether they live with adult children | |||

| Yes | 64.48% | 67.79% | 58.73% |

| No | 35.52% | 32.21% | 41.27% |

| Whether they own property | |||

| Yes | 50.81% | 50.63% | 36.56% |

| No | 49.19% | 49.37% | 63.44% |

| ln (value of owned property) quartile | |||

| Quartile 1(0.26,0.18,0.49) | 7.44% | 6.57% | 6.78% |

| Quartile 2(0.69,0.69,1.10) | 56.59% | 64.65% | 14.85% |

| Quartile 3(1.61,1.10,2.20) | 12.15% | 3.38% | 53.50% |

| Quartile 4(3.00,3.69,7.70) | 23.82% | 25.40% | 24.87% |

| ln (total value of fixed assets) quartile | |||

| Quartile 1(4.61,3.91,4.61) | 5.56% | 5.42% | 5.63% |

| Quartile 2(6.91,7.24,7.25) | 40.85% | 44.78% | 44.38% |

| Quartile 3(8.70,9.26,9.31) | 28.93% | 24.97% | 24.93% |

| Quartile 4(10.63,11.66,12.18) | 24.66% | 24.83% | 25.06% |

| Dimension | Indicator | Deprivation Cutoff |

|---|---|---|

| Economic (1/4) | Household consumption (1/12) | If household consumption is lower than the poverty line, it is 1. Otherwise, it is 0. |

| Durables (1/12) | If the total value of durables and financial minus debts is lower than individual poverty line, hen the number of adults is 1; otherwise, it is 0. | |

| Own property (1/12) | If the household does not own property, it is 1; otherwise, it is 0. | |

| Health (1/4) | Health condition (1/8) | If at least one family member has bad health, it is 1; otherwise, it is 0. |

| Regular physical examination (1/8) | If a least one family member does not take regular physical examination, it is 1; otherwise, it is 0. | |

| Employment and social security (1/4) | Stable job (1/12) | If at least one family member is without a job, it is 1; otherwise, it is 0. |

| Medical insurance (1/12) | If at least one family member is without any medical insurance, it is 1; otherwise, it is 0. | |

| Pension (1/12) | If a least one family member is without any pension or they only have old-age pension, it is 1; otherwise, it is 0. | |

| Family support (1/4) | The number of elders in household (1/12) | If there is more than 1 elderly member in the household, it is 1; otherwise, it is 0. |

| Marital status (1/12) | If more than 1 family member is divorced, it is 1; otherwise, it is 0. | |

| Family financial support (1/12) | If they do not receive any financial support from other family members in a survey year, it is 1; otherwise, it is 0. |

| Variables | Coefficient | Standard Error |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | ||

| The head of household’s age | 0.06 (***) | 0.02 |

| The number of elders in the household | 0.89 (***) | 0.45 |

| Whether the head of household belongs to the Chinese Communist Party | −1.90 (***) | 0.35 |

| Whether they belong to an ethnic minority | −0.26 (***) | 0.30 |

| The head of household is married | 0.99 (***) | 0.30 |

| Type of the head of household’s employment | ||

| Civil servant | −0.21 (**) | 1.09 |

| Institutional employee | −0.37 (*) | 1.13 |

| Farmer | 10.59 (**) | 2.82 |

| NGO employee | 1.70 (***) | 0.44 |

| Enterprises’ employee | 3.80 (***) | 0.41 |

| Self-employed | 3.08 (***) | 0.30 |

| Type of pension | ||

| Government and institutional pension | −0.57 (**) | 0.48 |

| Enterprise employee pension | −0.51 (**) | 0.31 |

| Commercial pension | −1.53 | 1.19 |

| Life pension | 0.54 | 0.53 |

| Rural residents’ pension | −0.06 | 0.20 |

| Urban residents’ pension | −0.11 (*) | 0.29 |

| Old age pension | 0.035 | 0.36 |

| ln (annual pension for the head of household the last year) | −0.08 (**) | 0.04 |

| Regular physical examinations for the head of household | −2.32 (***) | 0.24 |

| Type of medical insurance the head of household owned | ||

| Urban employee medical insurance | −1.48 (*) | 0.98 |

| Urban resident medical insurance | −2.42 (**) | 0.97 |

| New Cooperative Rural Medical Insurance | −1.25 (*) | 0.74 |

| Private medical insurance | −6.67 (**) | 0.041 |

| Household characteristics | ||

| Whether the head of household has the responsibility of caring for children | 0.48 (***) | 0.19 |

| Whether the head of household lives with adult children | 2.40 (***) | 0.24 |

| Whether the head of household owns property | −1.07 (***) | 0.19 |

| ln(value of the head of household owned property) | −1.27 (***) | 0.07 |

| ln(total value of fixed assets the head of household owned) | −0.64 (***) | 0.06 |

| Integrated variables | ||

| Urban employee medical insurance*age | 0.83 (*) | 0.56 |

| Urban resident medical insurance*age | 1.35 (***) | 0.58 |

| New Cooperative Rural Medical Insurance*age | 0.50 | 0.44 |

| Private medical insurance*age | 4.11 (***) | 1.57 |

| Number of observations | 3425 | |

| Variables | Coefficient | Standard Error |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | ||

| The head of household’s age | 0.11 (***) | 0.01 |

| The number of elders in the household | 1.58 (***) | 0.19 |

| Whether the head of household belongs to the Chinese Communist Party | −1.51 (***) | 0.12 |

| Whether they belong to an ethnic minority | 1.53 (***) | 0.13 |

| The head of household is married | 1.21 (***) | 0.14 |

| Type of the head of household’s employment | ||

| Civil servant | −0.06 (***) | 0.48 |

| Institutional employee | −0.41 (*) | 0.85 |

| Farmer | 2.50 (***) | 1.39 |

| NGO employee | 0.44 | 0.36 |

| Enterprises’ employee | 1.35 (***) | 0.20 |

| Self-employed | 2.97 (***) | 0.008 |

| Type of pension | ||

| Government and institutional pension | −0.25 (**) | 0.36 |

| Enterprise employee pension | −0.22 (*) | 0.27 |

| Commercial pension | 0.34 | 0.69 |

| Life pension | −0.04 | 0.42 |

| Rural residents’ pension | −0.03 (**) | 0.02 |

| Urban residents’ pension | −0.05 (*) | 0.14 |

| Old age pension | 0.82 (**) | 0.16 |

| ln (annual pension for the head of household the last year) | −0.07 (***) | 0.02 |

| Regular physical examinations for the head of household | −1.27 (***) | 0.67 |

| Type of medical insurance the head of household owned | ||

| Urban employee medical insurance | −1.66 (**) | 0.86 |

| Urban resident medical insurance | −5.11 (***) | 0.62 |

| New Cooperative Rural Medical Insurance | −1.93 (***) | 0.31 |

| Private medical insurance | −1.08 (*) | 0.60 |

| Household characteristics | ||

| Whether the head of household has the responsibility of caring for children | −0.42 (***) | 0.08 |

| Whether the head of household lives with adult children | −2.94 (***) | 0.09 |

| Whether the head of household owns property | −0.058 (***) | 0.07 |

| ln(value of the head of household owned property) | −1.23 (***) | 0.05 |

| ln(total value of the head of household’s fixed assets) | −0.49 (***) | 0.02 |

| Integrated variables | ||

| Urban employee medical insurance*age | 0.93 (**) | 0.47 |

| Urban resident medical insurance*age | 2.92 (***) | 0.34 |

| New Cooperative Rural Medical Insurance*age | 1.11 (***) | 0.18 |

| Private medical insurance*age | 1.08 (*) | 0.60 |

| Number of observations | 11,751 | |

| Weighted Variables | Mean Control | Mean Treated | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vulnerability rate | 0.467 | 0.412 | −0.055 *** |

| 0.383 | 0.370 | −0.013 | |

| 7.428 | 7.435 | 0.006 | |

| 61.022 | 62.826 | 1.804 ** | |

| 0.605 | 0.543 | −0.062 | |

| 0.612 | 0.587 | −0.025 |

| Weighted Variables | Mean Control | Mean Treated | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vulnerability rate | 0.343 | 0.277 | −0.066 *** |

| 0.390 | 0.392 | 0.002 | |

| 8.216 | 8.456 | 0.240 | |

| 62.360 | 63.144 | 0.784 * | |

| 0.580 | 0.568 | −0.012 | |

| 0.661 | 0.592 | −0.069 |

| Variable | Vulnerability Rate | Standard Error |

| Before | ||

| Control group | 0.467 | |

| Treated group | 0.412 | |

| Difference(T-C) | −0.055 *** | 0.007 |

| After | ||

| Control group | 0.439 | |

| Treated group | 0.373 | |

| Difference(T-C) | −0.066 *** | 0.011 |

| Difference-in-difference | −0.011 ** | 0.013 |

| Variable | Vulnerability rate | Standard Error |

|---|---|---|

| Before | ||

| Control group | 0.343 | |

| Treated group | 0.277 | |

| Difference(T-C) | −0.066 *** | 0.009 |

| After | ||

| Control group | 0.320 | |

| Treated group | 0.192 | |

| Difference(T-C) | −0.128 *** | 0.016 |

| Difference-in-difference | −0.062 ** | 0.022 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ding, S. Vulnerability to Poverty in Chinese Households with Elderly Members: 2013–2018. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4947. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15064947

Ding S. Vulnerability to Poverty in Chinese Households with Elderly Members: 2013–2018. Sustainability. 2023; 15(6):4947. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15064947

Chicago/Turabian StyleDing, Shuo. 2023. "Vulnerability to Poverty in Chinese Households with Elderly Members: 2013–2018" Sustainability 15, no. 6: 4947. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15064947