Abstract

Collaboration has the potential to aid the balancing of values and goals that belong to different, sometimes competing, policy fields, such as energy, climate adaptation and nature conservation—a key component of sustainable governance. However, we need to know more of how collaboration can function as integrating (and integrated) components of governance systems. Three regulated Swedish rivers are used here as examples to explore factors that influence this function. The following factors are identified: transparency of value trade-offs, understanding of collaboration and governance, interplay between public sectors, integrating funding mechanisms, clarity of mandate, strategic use of networks and consistency of the governance system. As a consequence of the poor management of these factors in our case, water quality and ecology values are not integrated in strategic decision making, e.g., regarding hydropower, urban development or climate adaptation. Instead, they are considered add-ons, or “decorations”. The Swedish case illustrates the meaning of the factors and their great importance for achieving sustainable governance.

1. Introduction

The development of governance that supports sustainable societies has been on the agenda for several decades (see [1,2] for overviews). The complexity of socio-ecological systems is at the core of this endeavor, including management of wicked problems [3]. As exemplified by the diversity of the Sustainable Development Goals, governance of complex systems involves multiple factors that are dynamically connected across policy fields, geographies and temporal scales. It is well-established that sustainable governance therefore needs to operationalize the principle of integration—across perspectives, disciplines, actors, sectors and geographical scales [3,4,5]. To accomplish such integration, participation and collaboration are frequently forwarded as a central component [6,7]. In addition to including knowledge and perspectives, participation and collaboration can also bridge administrative and geographical scales and help identify and deliberate on value conflicts, which in turn can make decisions more legitimate and simplify their implementation [8].

From the vast literature on collaboration, we know much about what makes collaborative groups work well. A large number of case studies and reviews have identified “factors for successful collaboration”. Very shortly, such factors concern funding and resources, internal communication, shared goals and understanding and socio-psychological factors such as creation of trust, conflict management and leadership, e.g., [9,10,11,12]. From the perspective of sustainable governance, factors concerning the integration of participation and collaboration initiatives into the wider governance system are likewise important [13,14]. However, around these factors there is a considerable lack of knowledge [15,16,17,18]. Collaborating groups are commonly studied as units that are disconnected from the wider governance setting [12], and studies where collaborations are examined against criteria that go beyond group members’ experiences and objectives are rare [19,20].

We explore stakeholder collaboration around rivers that produce climate-friendly electricity, have high ecological values and are subject to flooding. The regulation of river flow explicitly connects values that typically belong to different policy fields and sectors. Water governance, and the selected rivers, make exemplary study objects for the success factors of what we call the ‘collaborative capacity’ for sustainable governance. By collaborative capacity we mean how well a governance system meets already well-known factors for successful collaboration, plus the factors for integration of collaboration into the wider governance system which this study focuses on. Thus, in view of the overall aim here—to contribute to sustainable governance—the objectives of this study are:

- to generate knowledge of factors that influence the integration of collaboration into the wider governance system in general terms;

- to formulate a set of specific recommendations to support the developments of water governance in Sweden.

2. Collaborative Capacity: An Integrated Theoretical Standpoint

Collaboration research, when studied from perspectives of complexity, sustainability and resilience, implicates a system perspective. From a group perspective, or in relation to a particular project, collaboration may work fine but may still fail to be integrating—across disciplines, across policy fields and across geographical and administrative scales. Examples of key questions that a system perspective enables are: How can the often elusive mandate of a collaborating group be aligned with the mandates of other key actors? How can transparency and accountability be accomplished in a system that rests heavily on collaboration? How can collaboration help balancing values that belong to different, potentially competing, policy fields? Studies that specifically examine how participation and collaboration can be integrated in their governance systems are needed for advancing our knowledge of sustainable governance.

Studies and theories of collaboration and its relation to governance include a multitude of intra- and interdisciplinary perspectives from political science, cultural geography, public administration, planning, resilience studies, ecological economics and others, e.g., [21,22,23,24,25]. Depending on their disciplinary viewpoints, traditions, experience and objectives, these disciplines and fields contribute important pieces of knowledge about collaboration and how governance structures that are able to effectively integrate collaboration into the governance system, and can be understood and established [25,26]. Because the issues of collaboration and its relation to governance are so broad and multifaceted, current research and theoretical frameworks tend to limit the study to a specific part of the broad array of research issues, e.g., [27,28,29], or attempt to capture a larger part by maintaining a high level of abstraction, e.g., [21,22,25]. To explore the factors that affect the integration of collaboration into the governance system, we need to capture the full breadth of this complex issue while maintaining a certain level of detail. To that end, we use a simplified version (principle and themes) of the sustainable procedure framework (SPF) to analyze the collaborative capacity of the Swedish water governance system. For a full description of the SPF and how it was derived, see [30]. The framework provides:

- a theory-based analysis of collaboration;

- a (governance) system perspective on collaboration (through inclusion of issues such as representation and organizational integration);

- explicit links between collaboration and the concepts of ‘integration’ and ‘sustainable development’.

In short, the framework utilizes two fundamental sustainability principles—integration and participation—as points of departure (Table 1). These are well-established principles of sustainable development, and by far the most cited sustainability principles of process character [31,32]. Based on these, criteria for a sustainable planning process have been derived through an extensive literature review and synthesis and through interviews with key researchers [30,33]. Sixteen criteria are structured into five themes: integration across disciplines (1), across values (2) and across organizations (3), and participation to contribute to the process (4) and to generate commitment, legitimacy or acceptance (5). Research has been synthesized from several inter-disciplinary fields, such as integrated and adaptive management, collaborative planning, multi-level governance, deliberative democracy and ecological economy (ibid). The framework thereby synthesizes and integrates scientific knowledge structured through the concept of sustainable development. It also captures key factors that have been identified for successful collaboration in the literature, including the factor that this study focuses on, i.e., connecting collaboration structures to its wider governance setting. The SPF is therefore useful for exploring collaboration from a governance system perspective—the system’s collaborative capacity.

Table 1.

A simplified version of the sustainable procedure framework (SPF; principles and themes; Hedelin [30], including our analysis questions, specifying the focus of the study.

3. Method

We use an in-depth case study design. The idea is to use selected collaborations as starting points to examine the collaborative capacity of the wider governance system. In a system with good collaborative capacity, we expect to find structures and conditions that shape and support our collaborations so that they can function as integrating and participatory governance system components.

Because factors related to collaboration are context-dependent, we use three regulated Swedish rivers (Emån, Klarälven and Ätran) that are similar in the key circumstances that we are interested in, but vary in other aspects (e.g., locations, actors, social relationships, land owner history). All cases include complexity in terms of governance structure, societal investment and commitment to the development of collaborative structures, and an explicit need to handle trade-offs of values that belong to different policy fields (such as energy, ecology and flooding). Through this choice, we include numerous and variated collaboratory aspects and contexts which suit the exploratory nature of this study. Before we describe the cases in detail, data collection and analysis are outlined:

- Interview guide: includes both specific and open-ended questions (Table 2).

Table 2. Outline of the interview guide.

Table 2. Outline of the interview guide. - Interviewees: were selected via respondent-driven sampling. This is a non-probabilistic sampling technique, where existing study subjects recruit future subjects from among their acquaintances. This method is often called the snowball technique. The focus is on the water councils in each of the three river basins, i.e., their respective chairpersons.

- Interviews: 44 interviews were performed spring 2019, evenly distributed amongst the rivers. All interviews were conducted via phone or through a digital platform (video). During the interviews (1–2 h long), notes were taken in an Excel file that had been developed and tested beforehand.

- Analysis (two-step): Empirical part: A thematic analysis of the interviews was performed [34] where responses are analyzed as a whole. The purpose was to generate a deeper understanding of existing collaborations with a focus on organizational-structural conditions and a close-up description of respondents’ experiences of the ongoing work. Theoretical part: Building on the thematic analysis, the analytical framework (the SPF; Table 1) was used to explore factors influencing the collaborative capacity of the rivers’ water governance system.

3.1. The Case: Water Governance in Sweden

Water physically connects different claims as it flows through the landscape, transporting goods, substances and energy. The necessity of balancing values related to water is often explicit. Possibly because of this, implementation of participatory structures for integrated management have come relatively far in the water sector [35,36]. During the last decades, strategies for integrated and participatory water management have been implemented in different parts of the world see, e.g., [36,37].

In Sweden, governance structures stretch from the European level to the very local, river-scale level. The last decades’ integrated and participatory turn in water management has been manifested through EU legislation on river basin management, targeting both water quality and quantity through the Water Framework Directive (WFD) and its sister directive, the Floods Directive (FD) [38,39]. Both directives include two central ideas. Firstly, water management should be performed in an integrated way with the river basin as its geographical basis, and secondly, to achieve such integration, collaboration between different actors is key [40].

Implementing these directives into the member states’ national systems for land-use planning, environmental and water governance has proven to be complicated [41,42,43]. Sweden is reported as a special case, having made extensive changes to the national water governance system due to the WFD [43]. Despite great engagement and intentions, water governance in Sweden is characterized by complexity and fragmentation, including ambiguous and heavily overlapping mandates, unbalanced administrative and operational powers and democratic deficits [44,45]. An important reason is that the current water governance system in Sweden is still much influenced by the situation before the WFD [43]. In short, water and land-use planning has long been—and still is—integrated through the local land-use planning mandate. Here, the 290 local municipalities, governed by locally elected politicians, are key actors. The Swedish municipalities’ far-reaching mandates are often referred to as the “local planning monopoly” [46]. The municipalities are also the key actors for other water and infrastructure related issues such as water and drainage systems, waste, traffic, energy planning, risk management and preparedness. The regional authorities (County Administrative Boards, CAB) mainly lack steering power in Sweden, and have long acted as the extended arm of the central government. However, the CABs oversee the implementation of national legislation regionally, but have limited influence over actors with formal powers to influence land use, i.e., private land-owners such as farmers or forest owners, public forest corporations, and the municipalities [47,48]. The central government has the legal power, controls the financial system and organizes expert authorities that issue guidelines and handbooks [49,50].

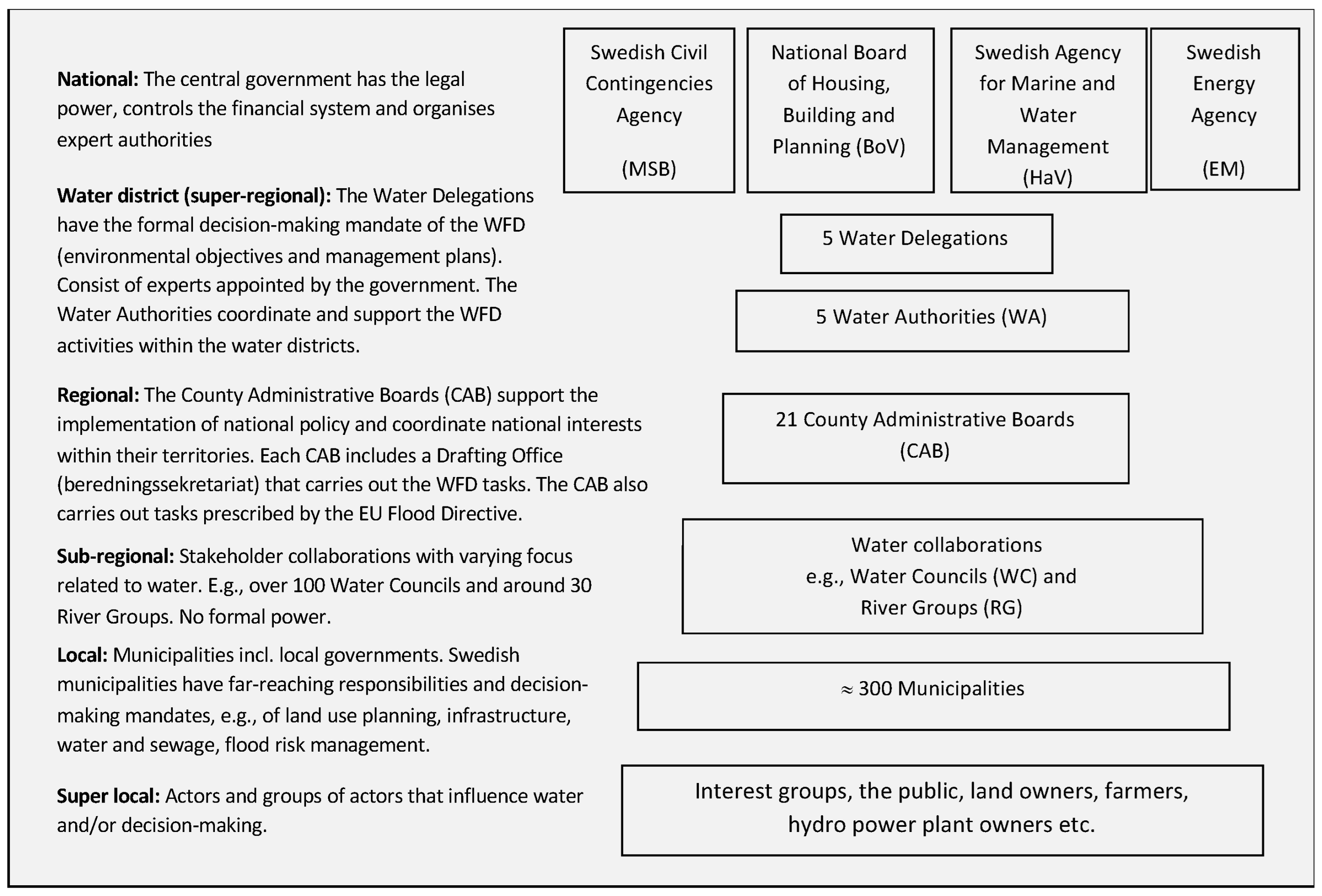

When implementing the WFD, water administration based on river basins was established in parallel with the municipal planning system [51]; Figure 1. Sweden was divided into five super-regional water districts, with catchments that drain into one of the major sea basins. A Water Authority (Vattenmyndigheterna in Swedish), responsible for putting the WFD regulations into practice, was appointed for each district, as well as five Water Delegations, with experts appointed by the government, possessing the formal decision-making authority. The practical WFD tasks are carried out at the CABs: water characterization, classification, monitoring, control, definition of binding environmental objectives (Miljökvalitetsnormer, MKN in Swedish), drafting of management programs and plans, and interacting with stakeholders. Later, an authority at the national level was founded to coordinate the five Water Authorities: the Swedish Agency for Marine and Water Management (HaV).

Figure 1.

The main actors of Swedish water governance, from national level to super-local.

The FD came after the WFD. Compared to the WFD, its implementation took more advantage of the actors and structures already in place in the Swedish system for handling flood risks, including their mandates and roles [52]. The tasks prescribed by the FD are performed by the Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency (MSB; guidelines, mapping and reporting), and the CABs (risk assessment and drafting of the non-binding flood risk plans).

3.1.1. Water Collaborations

A main strategy in Sweden for achieving active participation, as mandated by the WFD, has been the creation of more than 100 Water Councils (WC) at the sub-river basin scale. Participants include industries, municipalities, farmers, hydropower companies, forest owners, fishing organizations, environmental organizations, etc. [43]. The WCs do not have any formal mandate or power. They function as sounding boards for WFD work, and comment on proposals developed by the CABs, providing basic data and developing their own proposals for classifications, measures and consequence assessments [53]. The WCs are supported by the Water Authorities, which finance part-time coordinators.

Even though the FD prescribes that all affected parties should be encouraged to actively participate in flood risk planning (similar to the WFD), no new or extended forms for participation or collaboration have been established as a result of the FD. However, River Groups focusing on monitoring and coordinating activities for managing high flows have existed for about 30 rivers [54]. Participants are typically river-regulating companies, hydropower producers, municipalities (crisis and preparedness, planning) and CABs (convening). These groups have as of now no prescribed role in the organizational set-up for fulfilling the FD.

These aforementioned collaboration structures related to the WDF and the FD are the main ones related to our study, but an array of other types related to water also exist.

3.1.2. Reconsidering Swedish Water Governance

In view of the described problems associated with the complexity of the Swedish water governance system, the government has issued a public enquiry. It investigates the division of responsibility, decision making and organization of the authorities involved, and proposes changes for a more effective and coordinated administration including organizational changes and an extended focus on river basin collaboration [55].

In parallel, the Swedish hydropower sector is under reconstruction, related to the demands from the WFD. All licenses for river regulation will be renegotiated (Ministry of Environment, 2020). Approximately 45% of Sweden’s electricity production comes from hydropower and the number of regulated rivers is large, with over 2000 hydropower plants [56]. Relicensing will continue until after 2040 and involve a large number of complex legal processes. During these processes, all the main values related to river regulation will need to be considered, such as climate-friendly energy, river ecology and flood risk management. To prevent long-lasting legal processes stalled by repeated appeals, which would be very costly, the water administration hopes for stakeholder collaboration to prepare the ground for the formal processes of the environmental courts.

3.1.3. The Regulated Rivers

Three rivers have been selected as study objects: Klarälven, Ätran and Emån (Figure 2). All rivers are regulated for hydropower and hold high ecological values that are negatively affected by flow regulation [57]. All three rivers have also experienced flooding events. Flood risk threatens the surrounding urban areas with social disturbance and high costs for damaged infrastructure. Thus, these rivers explicitly connect three important risk and environmental values—climate friendly energy, local ecology and flood risk safety—and therefore function for studying governance across policy fields and sectors in the context of sustainability.

Figure 2.

The location of the case rivers: Klarälven, Ätran and Emån.

River Ätran is situated in southwestern Sweden. It has a catchment area of 3342 km2, and a mean annual discharge of 51 m3/s. It empties into the North Sea and mainly includes four municipalities. The possibility for fish to pass through any of the hydropower dams was extremely limited prior to 2007. Since then, researchers have worked together with power companies Uniper, Falkenberg Energy and local authorities in establishing fish passage facilities in the river. The collaboration around water in the River Ätran has a long tradition emerging from the need for clean water for fishing.

River Emån, with more species of fish than any other river in Sweden, has a catchment area of 4472 km2, a mean annual discharge of 30 m3/s and mainly includes eight municipalities. The possibility for fish to pass through the hydropower dams was limited prior to 2000, when researchers from Karlstad University together with the power company and local authorities enhanced the possibility for fish passage in the river. Collaboration focused on the river has evolved over the past 20 years.

River Klarälven, with a catchment area of 11,850 km2 and a mean annual discharge of 163 m3/s is home to populations of migrating, large-sized, landlocked Atlantic salmon and brown trout. The catchment mainly includes six municipalities. There are no passage facilities in most of the river, but extensive ecological studies, conducted since 2007 by Karlstad University in collaboration with the power company Fortum and local officials, have resulted in plans for establishing fish passage in the river. Collaborative efforts in Klarälven have a relatively long tradition mainly due to energy production.

4. Result

The first part of the result presents the thematic analysis of the interviews. The second contains the theoretical analysis and the formulation of collaborative capacity factors.

4.1. Description of River Collaborations

The analysis resulted in three themes: involved actors, organization and the development of water management in the river basins. Quotes and statements are referenced by using the first letter in the rivers’ names (E/K/Ä).

4.1.1. Involved Actors

Table 3 outlines the collaborations with respect to the organizations and values represented, the geographical scales, working experience and educational background.

Table 3.

Overview of respondents per river basin. (n) shows number of respondents.

With regard to the values represented in the collaborations, there is a strong dominance of water ecology and nature conservation values. Furthermore, the link between water quality and flood risk management seems to be weak, i.e., flood risk was only mentioned a handful of times in total and then only in general terms referring to the River Groups. However, some of the comments indicate the link has grown stronger over time. This is especially visible in Emån, where the link between the FD and WFD seems to have a stronger foothold mainly due to previous experience with inundation, but also because it is linked to the hydropower relicensing process and there is a lack of water for different types of use. The link between ecology and hydropower is generally more developed. One third of the respondents mention hydropower, referring to the relicensing processes, to the adverse effects of hydropower and to the power industry’s strong lobbying effort.

A majority of the respondents argue that the types of organization involved in water management and the amount of interaction have increased over time. The actors frequently mentioned are the general public, politicians and universities.

A majority of the respondents have a natural science background, focusing on nature protection and water quality. Many of them have been working in the area for a relatively long time (on average 12 years). Respondents that were comparatively new to the job have in general previously worked in a similar type of organization. A slight diversification in the educational background of the respondents can be discerned over time where more than half of the newcomers (1–5 years) have another educational background than natural science. One respondent reflects:

“It is important that those who lead these processes are not die-hard biologists. We have actually hired the wrong people. For example, hydromorphology is completely lacking. They are aquatic biologists and some are really narrow, for example fish biologists. We would need behavioral scientists and sociologists to lead these processes. Political scientists are also needed at the regional level.”(K)

4.1.2. Organization

Despite similar organizational structures (number of members, represented organizations and form and regularity of meetings), smaller differences can be discerned between the river collaborations regarding leadership, structures and activities.

Concerning leadership, the influence of an individual champion (a person driving the development in an organization) is especially visible in Klarälven and Ätran, as illustrated by: “X is an incredibly central person. Works on a non-profit basis but has an incredible amount of knowledge. Leads and drives. Many projects would not have been possible without X” (K). In Klarälven, the champion is mainly mentioned in a positive context. In Ätran, a (former) champion or central person is mentioned in more negative words; the person hindered the development of river basin management due to a too strong personal fishing interest. In Emån, there is a clearer core group of persons instead of a single champion.

In Klarälven, several of the respondents testify to a strong focus on projects. There are also several comments on differences in the work of CABs and leadership traditions, e.g., in relation to project applications, which influences the daily work of the CAB personnel. These comments emerge from the fact that several of the respondents have work experience from more than one CAB. The possibility to apply for funding differs between the CABs, and some of the WCs apply for and receive more money than others, which mainly seems to be linked to different conditions for working with project applications, such as time and encouragement.

Externally funded projects play a central role in the development of the WCs work, and can even be described as constituting most of the work. The projects are financed by the Swedish Agency for Marine and Water Management (HaV), administered by the CAB. Most projects focus on water status and recipient control, and financing has increased over time. Several of the respondents are welcoming a new funding scheme with the purpose of assisting the WCs in the coordination of projects. The respondents comment that this would provide them with the possibility to actually start to coordinate the work in a more organized way. Project money is deemed fundamentally necessary when carrying out measures for liming and nature conservation when land owners are involved. One respondent describes this:

“We visit landowners (mostly agriculture and forestry) to get them to take measures, for example with support from the WFD and Natura 2000. Sometimes you can entice them with project money or with reduced flood risk; work with trust, set-up written agreements with landowners. Often they may be interested in reducing flood risks and then nature conservation measures can be included in the agreement.”(E)

The hydropower industry’s environmental fund (Vattenkraftens miljöfond in Swedish), set up for financing legal costs and measures connected to the relicensing, is also mentioned by several of the respondents. They see it as a potential to increase future water management activities as well as a way to integrate the interests of different actors. Respondents find that more project money leads to more collaboration and action.

Networks: There are many comments related to the role of the WCs as facilitators and developers of networks, both at the local scale but also between local and regional scales, and even the national scale. Typical expressions are: “We must have cutting-edge expertise that the municipalities can use” (K), “National competence network for consensus” (K), “At the heart of things” (E). It is clear from the respondents of all rivers that they perceive the developed WC networks as central, and many argue that they have become stronger over time. In the river basin where a strong champion was identified, the networks are closely tied to that person.

Two different topics related to the functioning of the networks could be discerned. The first issue is related to competing values, as illustrated by: “…bad at communication when competing intersts leads to debate… However, the dialogue continues” (K). The other topic concerns the fact that the status description consumed so much time that little time was left to actually collaborate and strengthen the networks.

Communication is a large part of the work. A range of activities directed to the general public is described: information campaigns, member meetings, thematic days, newsletters and site visits. One respondent says: “The WCs are good for knowledge transfer up and down [back and forth from the WC to the public]” (Ä). Some of the respondents, especially in Klarälven and Ätran, explain how their outreach and awareness raising activities have evolved over time and become bigger, better organized and involve more people.

Outreach activities are appreciated by several of the respondents and several argue that it creates momentum around water management. A particular type of interaction is discussions with land owners. One respondent describes these deliberations as an efficient way to engage and create legitimacy in relation to water management in a broader sense, e.g., development of joint projects that can reduce risk for flooding and at the same time protect nature (E). Other groups particularly targeted with information are local politicians and the public since their knowledge of water environmental issues and of the WC is perceived as very limited.

One respondent argues that they have gained knowledge on how to communicate risk with stakeholders (Ä). One respondent says that they are bad at communication when there are competing interests (E).

4.1.3. Development

It takes time: Many respondents bring up the need for time to develop a new water management approach, specifically to get accustomed to the focus on river basins. The 6-year working cycle that came with the WFD and FD is also new. It takes time to get accustomed to, but many also see the benefits of it as the focus may change as one learns more, e.g., “Several environmental problems were raised that were not previously raised or perceived as problems [before the WFD], such as fish migration times and hydropower regulation. It has brought the work on water together in a good way. That environmental issues also apply to water.” (K) A similar view about the work in the WC is expressed: “Many think that it is starting to become established now”.

Furthermore, one respondent argues that data uncertainties have been reduced as the prognosis for water flows has improved over time.

“Everything is more open and free now, from SMHI [Swedish Meteorological and Hydrological Institute] for example” (K).

Several mention that now there is a larger acknowledgement of the complexity of managing water and of the need to be flexible and open to new water issues than previously during the implementation of the WFD. Others explain that the changing focus of water issues over time, from, for example, fish to hydropower (Ä) and from recipient control and liming to broader water management issues (E), is something positive. One respondent says: “An increased focus on water energy accentuated the conflict between inundation and ecological quality, which clarified the essence of the problems related to flooding that had not been highly prioritized earlier. This in turn created stronger interlinkages between the Water Councils and the River Goups” (E).

Building relations: Many respondents stress that collaboration structures have had a positive development over time (K, E, Ä). When referring to different activities, the respondents indicate that when dialogue has been initiated, it has resulted in increased understanding between different groups in relation to, for example, fishing and nature conservation interests, land owners and water authorities. Moreover, several respondents have observed that interactions create engagement both from themselves and from other groups, as in the case of liming (K), e.g., “We work with trust, write agreements with landowners. … A lot of psychology in this work. When a “big” farmer does something, there are ripples on the water” (E).

Some respondents also comment on the form of building relation through collaboration: “We have found better forms of cooperation: the municipal’s internal water directive group, which was formed when the WFD first came, has been more active in the last 10 years. Then, the WC has also developed positively and so have the coordinators in charge of remedial measures in the LEVA project” (Ä).

Conflicts: The respondents talk about conflicts, especially in relation to nature conservation and fish, hydropower, inundation and recreation. This seems to be most pronounced in Klarälven. For example, one respondent argues that there are “constant conflicts with authorities about projects involving the fish stocks” (K) and “The Flood Directive and the WFD are not in sync, they are run completely without coordination of the different actors. For the ecology, floods are often regarded as good, so there are conflicts here” (K).

In relation to issues involving conflict, respondents argue that they either avoid such issues or try to be careful to avoid conflicts. “Hydropower is the difficult part, there is a lot of conflict there. It’s hard to move forward, we don’t work with this” (E).

Related to conflict, several respondents explain that the Court of Justice of the European Union’s Weser case (C-461/13, 1 July 2015) has drastically altered the conditions for local water management and infused it with uncertainty: “The EU has had an infringement case against Sweden for several years. They argue that we have not used MKN [the environmental objectives] in the right way, that they should be more similar to limit value standards in their function, i.e., more clear. … And this has led to greater political interest in the WFD and that we have had to deal with the issue of relicensing hydropower.” (Å).

Lack of power: Several respondents from all three rivers raise the lack of power in relation to water management (including inundation and hydropower) as an important issue influencing their ability to work. This is brought forward in relation to the WCs’ lack of influence on decisions and development projects that are indirectly related to water. Lack of power may be explained by the relation between local water politics and the WC to some extent, which appears to be relatively weak in all three river basins. One respondent (E) underlines that a major problem with the involvement of politics is the short election periods and the absence of local water policies. While the WCs seem to be weak in relation to local politics, lack of power is also mentioned in relation to the municipalities’ influence over the hydropower companies: “…ultimately cooperation does not help if you do not have a mandate to make decisions. When it comes to the really big things, reassessment of legal water decisions is needed.” (Ä).

Several of the respondents mention that the power of the WCs is related to the number of projects they have, indicating that the WCs’ power is fragmented and linked to the ability to attract project funds. Another respondent argued that the power of the WC largely depends on the members of its board.

4.2. Factors for Collaborative Capacity

The analysis and factors presented here are based on the empirical description abovementioned, studied through the theoretical lens of the sustainable procedure framework and its five themes (Table 1). The themes contribute from different perspectives to the formulation and understanding of collaborative capacity factors that influence the integration of collaboration into the wider governance system. The generated factors are numbered and referred to in Table 4.

Table 4.

A list of the identified factors for collaborative capacity, and of their state in the Swedish case.

4.2.1. Integration across Disciplines

Most of the respondents have a natural science background. Backgrounds involving organizational, legal or participatory skills are largely missing. Several of the respondents felt that too much focus has been put on water status and too little on developing the organization, i.e., what role the organization should have and what goal it should work towards. This situation may be caused by the strong dominance of the natural science background in the actor network. With a gradual change in focus of water issues and the subsequent inclusion of new actors with new disciplinary backgrounds, the diversity of educational backgrounds is increasing over time. Even though the work in the WCs has focused on water status, several comments from the civil servants working at the CAB indicate an increasing understanding of the complexity of water management and show an ongoing learning process towards an integration of a more diverse range of knowledge perspectives. As for knowledge support, the mapping activities are mentioned as central as they create a basis for action. Universities and national authorities are also mentioned as a source of expertise both in relation to specific projects as well as to make presentations at information days or following the process in specific projects. Collaboration structures developed between the WC and landowners through the implementation of specific projects are today perceived as learning and action platforms. However, the possibility to create long-term knowledge and learning platforms is limited as these collaborations mainly are financed through time-limited projects. Uncertainties are mainly mentioned indirectly, in relation to the continuous learning processes—both through collection of more data and by strengthening of local networks—and in relation to the EU court decision that affects the Swedish interpretation of the the WFD’s environmental objectives (MKN in Swedish). We cannot from the results of this study say why uncertainty is not discussed more explicitly; whether it is actually perceived as low, or, if there is a lack of understanding of how to communicate and manage uncertainty.

In conclusion, integration across disciplines is relatively weak in all case rivers, but it seems to increase over time. Four factors are governing this situation: transparency of value trade-offs (factor 1) and understanding of collaboration and governance (factor 2), which are both insufficient in our cases due to the heavy natural science focus of the work, interplay between public sectors (factor 3), which is too weak, and the lack of integrating funding mechanisms (factor 4). See Table 4 for a numbered list of all factors.

4.2.2. Integration across Values

Based on the interviews, we identified four different represented values, with nature protection and aquatic ecology being represented by most of the respondents. The second largest represented value is forestry, and thereafter hydropower (based on number of respondents). None of the respondents represent flood risk directly. As a result of the implementation of local projects, there is an ongoing learning process of how different values could be integrated, but what is actually integrated is, to a large extent, steered by what projects receive funding. Hence, funding mechanisms are governing the actions of the WCs. For example, Klarälven, which has had an individual champion with deep knowledge and interest in aquatic ecology, has led to successful funding involving this particular value. Moreover, the WFD’s relatively narrow focus on aquatic ecology, especially in relation to the first policy cycle of the WFD, and the lack of strong links to municipal politics as well as other water issues (flooding, hydropower), makes the integration between values low. Over time, structures to facilitate communication and collaboration have become stronger in all three rivers. Nevertheless, this increased capacity seems mainly related to project implementation, and has, to some extent, spread to the discussions held at the WCs and other networks at the local and sub-regional scales; however, value judgements across policy sectors are missing.

In conclusion, the studied networks and organizations have, to some extent, been able to support structures that integrate values at the local scale, within specific projects, but they have not been able to handle transparent and comprehensive value judgements at the river basin scale. This seems to be related to the mandate of the WCs and/or how their mandate is interpreted by key persons. Four factors govern this situation: clarity of mandate (factor 5) of the WCs, which is insufficient, weak interplay between public sectors (factor 3), strategic use of networks as governance structure (6), and integrating funding mechanisms (4).

4.2.3. Integration across Organization

The links between organizations seem to be getting stronger over time, especially as the hydropower issue becomes more pronounced due to the upcoming relicensing processes. Many respondents refer to the different networks they are involved in and the different administrative scales that they operate on. However, individuals representing municipal climate adaptation and urban development are not involved in the discussions, i.e., the planning departments of municipalities and River Groups. Moreover, as there are no overall water departments in municipal organizations, the municipal representatives in the WCs are merely representing the municipality as such, not an integrated municipal water policy. Hydropower actors seem slightly more integrated, which, according to the respondents, may be due to hydropower being an issue that potentially creates conflicts. The current organization of the WCs, which includes representatives from the regional level, facilitates administrative integration up to at least the regional level. It is, however, unclear to what extent the different public sectors are integrated at the regional level. In addition, project funding comes from the one policy sector at the time, which does not support cross-organizational collaboration in relation to applying for project funds.

In summary, integration across organizations is assessed as relatively weak as organizational structures between the policy sectors of flooding and water ecology are lacking at all administrative scales. Moreover, developed networks at the local level do not have any decision mandates and are mainly seen as collaboration platforms for learning rather than for making decisions. Four factors have been identified as governing this situation: interplay between public sectors (factor 3), the ambiguous division of roles between the local planning monopoly and the WFD administration in Sweden, which stems from a(n) (in-) consistency of the governance system (factor 7) for water issues, the lack of clarity of mandate of the WCs that follows (5), and finally, the lack of integrating funding mechanisms (4).

4.2.4. Participation—Contributing to the Process

In all three rivers, the connection between the general public and local politics seems relatively weak. The amount of effort to spread information about water management to citizens has, however, increased due to the WCs. Even if this does not allow the public to directly influence water management processes, it could indirectly influence local politics as more people (including local politicians) may increase their awareness of water as an issue that need to be considered. This indirect path of influence was not, however, something that was discussed in the interviews. The WCs have compiled considerable amounts of knowledge on water issues as well as learned how to collaborate. This knowledge is mainly used in relation to project development and implementation at the super local scale, while their influence on other water related decisions seems to be low. Direct links to decisions related to inundation, hydropower and municipal development are absent, except for in a few occasions when the WC has been a referral instance to local development plans. Decisions regarding development are taken by the municipalities or hydropower companies with very little involvement of the local public. The WCs and their networks mainly have power over implemented projects, but even here the contribution is limited as the origin of the project funding steers the content of the projects.

In sum, there is an increasing potential for local public involvement, but there are several limitations hindering a broader contribution to water governance. Three factors seem to govern this situation: the limited understanding of collaboration and governance (2), the lack of clarity of mandate of the WCs (5) and the low interplay between public sectors (3).

4.2.5. Participation—Generating Commitment, Legitimacy or Acceptance

There is an increasing number and variation in activities intended to promote participation, including outreach activities, collaboration through development of networks, and collaboration with landowners, especially in relation to liming and nature conservation projects. However, the respondents point to the lack of connection between the municipal planning processes and the WC. It is also so that direct interests such as hydropower and land ownership have a strong influence on the actual management. Nevertheless, implemented activities seem to have generated an increased commitment, legitimacy and acceptance at least at the super local (project) scale. The activities have had a relatively limited scope, however, and at larger scales and when there are strategic discussions regarding trade-offs between values of different public sectors, the studied networks seem to have very limited influence. In addition, we have not seen any indication that the overall distribution of national and regional resources, nor awareness of the values and interests that are actually benefiting from existing structures have been discussed in the networks. This is partly related to the public sector division of water issues, which makes it difficult to obtain an overview, and which may also explain why few of the respondents indicated any dissatisfaction with the current situation; it is difficult to judge if you are satisfied and feel that decisions are taken in a legitimate way if you lack an understanding of the whole (“big”) picture. These findings indicate that collaborative networks are being developed step by step. It is nevertheless too early to say if this has the potential to increase the possibilities for decisions to become more legitimate by including local citizens or local politics in a broader sense.

In conclusion, there is an increasing potential for participation generating commitment, legitimacy and acceptance at the project scale, but the lack of the “big picture” hinders the development of real commitment and legitimacy within the water governance system. Three factors govern this: clarity of mandate of the WCs (5), the interplay between public sectors (3), and the strategic use of networks (6). See Table 4.

5. Discussion

The factors that we identified as affecting the integration of collaboration into the wider governance system are interrelated, and although it is useful to formulate them separately, as in Table 4, they also need to be understood as a whole. To this end, we discuss the factors here drawing on current knowledge on collaborative governance and on Swedish water governance.

Governance includes setting priorities among competing values. In a vivid democracy, discussions of such priorities are held openly. If important value conflicts are involved, one might expect the discussion to be vociferous and widely acknowledged in for example the media. In Sweden, water has traditionally received low political attention [58]. Possible reasons are the extensive abundance of waterbodies, and/or that some values, which have been fundamental to the development of Sweden as a modern society, such as the benefits provided by hydropower, have a general acceptance relative to other values (e.g., water ecology). Compared to continental Europe, Sweden has experienced less problems with flooding, which can be explained by the relatively low level of urban development near water, the infrequency of catastrophic rainfall and snow melt [59] and the geophysical structure of Swedish rivers [60,61]. When the WFD came into force, around the turn of the century, this low political attention made it possible, even rational, to implement the WFD in a way that did not correspond well with Sweden’s political democratic system (factor 7, consistency of governance system), which, for water issues, rests heavily on locally elected politicians.

Furthermore, the scientific/expert character of the WFD did not contribute to the political perspective on water. With a tight timetable and a lack of data and guidelines for how to carry out the overwhelming and complicated natural scientific assessments of ‘good status’, the work became heavily focused on water ecology and natural scientific issues. Questions of where to go (i.e., politically negotiated “reasonable” targets for all lakes, rivers, groundwater aquifers, etc.) were overshadowed by more concrete matters of mapping and characterization of waters [62]. Additionally, the question of the role of the WFD’s environmental objectives related to the far-reaching municipal mandates of physical planning was left hanging (factor 7, consistency of governance system). This is supported by a country-wide evaluation of the WFD monitoring system, which shows that the main focus has been on ecological parameters [63].

Instead of being integrated into Sweden’s regular political system, the WFD was operationalized by a set of new national, super-regional and regional expert authorities compartmentalized within the environmental public sector, with no tradition of, and a unclear mandate for, making political decisions (prioritizing values). Additionally, despite the high ecological ambitions of the WFD and the potential value conflicts it would bring, water issues could carry on as being non-political, expert matters. The water experts were busy with the complicated, resource-demanding and stressful work of collecting data, characterizing and classifying all of Sweden’s 27,500 water bodies. Focus was set on understanding the ecological status and the definition of the “undisturbed” reference conditions for water bodies, enforcing the natural science focus of the WFD (1 Transparency of value trade-offs). The new and binding water environmental objectives, the programs of measures and the binding river basin management plans were all derived by the experts within the new water administration. Additionally, even though Swedish law establishes that the municipalities have the mandate to decide on water and land use within their territories, through their locally elected parliaments, the water administration was committed to the environmental standards of the WFD, and water was still not an issue on the political agenda.

Many pointed out the lack of consistency and logic between the WFD implementation and the legal mandates of Sweden’s local municipalities with their “planning monopoly” [64,65,66,67]. The Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions (SKR in Swedish) and the National Association for Water Supply (Svenskt Vatten in Swedish) criticized the way that municipalities were kept outside the WFD decision making while still being regarded as a key actor for the measures and costs it would bring, e.g., [68,69] (4 Integrating funding mechanisms). On the other hand, it can be argued that municipalities could have accomplished more to integrate the WFD into their own work processes. It is also essential to ask why has this not happened. A general answer is the perceived urgency of water quality issues and the political ideologies of the municipalities [70]. The lack of incentive from the municipalities to align their organization in relation to water (river basins) is also apparent in relation to climate adaptation [52,71,72].

Another criticism put forward is that the WFD’s general objective, “good status”—defined as a state with only small deviation from a theoretical/calculated reference state (i.e., unaffected by humans)—cannot be the target for all waters [62,73]. In Sweden, the main exception made from the general objective is for the largest regulated rivers—to prevent a large-scale closure of Sweden’s hydropower production. This way of interpreting the WFD can be viewed as very strict and contradicting basic components of a modern society such as industrial production, waste management plants, water and sewage treatment, farming, traffic and housing. The situation has been interpreted as a reluctance to apply EU law as interpreted by the Court of Justice of the European Union, which advocates flexibility in the WFD water governance system. Sweden has instead favored traditional legal certainty and a high level of environmental protection [64,74] (7 Consistency of governance system).

Several of our respondents mention the EU court decision [75] concerning the river Weser in Germany. The Weser court decision has clarified the legal meaning of the WFD’s objectives (termed Environmental Quality Standards, EQS; MKN in Swedish). From the court decision, it follows that activities that affect any of the subcriteria that define good water status negatively cannot be allowed. This, however, has not been the current way of interpreting the EQS according to our respondents. Instead, Sweden has interpreted the EQSs as goals or ambitions and not as strict standards (such as the standards for air and noise in Sweden; [64,74]. The interpretation of the water EQS as goals rather than strict standards may explain the fact that Sweden has not managed to reach the objectives for a large number of waters [74]. It may also, however, be seen as a pragmatic way of managing the overly enthusiastic and politically unrealistic EQS (1—transparency of value trade-offs; 5—clarity of mandate; 7—consistency of governance system). The EQS are based on natural science, and the possibilities of defining less stringent quality objectives (WFD’s opening for value-tradeoffs) have not been used much in Sweden [76]. This way of interpreting the EQS can be seen as a way to safeguard fundamental societal functions such as agriculture, industry, water and sewage treatment plants. Sadly, it may also have paved the way for activities that can be seen as less important from a societal perspective, with little social gain compared to its environmental costs.

The court decision, clarifying that the environmental objectives (MKN) are strict standards down to the subcriteria level, has several implications; most obviously, however, water has become political in Sweden. The relicensing of regulated rivers represents just the beginning. Moving forward, value disputes connected to water will hopefully be held in the open, and with representation of the main concerned actors, or by politicians, and deliberations will not only be held in courts where decisions are made by legal and natural science experts. Hopefully, we will see an increase of transparent democratic processes around what exceptions to allow from the general conservationist WFD objectives. Several questions are calling for answers here: Who should lead those processes, at what scales, and what role will the WCs play?

At an early stage of implementation, the new water administration in Sweden showed great commitment to the idea of participation [62]. This led to a drive to support the establishment of over 100 WCs. Such a task, however, is difficult without knowledge about organizing participation [77]. With participation mainly focusing on the super local level, lacking access to a more strategic level participation, it can easily become construed as tokenism, where local communities are perceived as coherent and cohesive bodies [78]. (2—understanding of collaboration and governance). With the implementation of the WFD in Sweden, the WCs have become the main organizational feature for participation, for crossing sectorial trenches and for discussing and managing competing water values. As the WCs have weak or unclear mandates, they are construed as networks. As we have seen, the WCs are used both as a strategy for achieving hands-on water management and as a solution to the lack of clear governance structures and political mandates associated with water. An important reason for this is probably the division of the public sector, as the study signals that issues of flooding, water quality and hydropower are not integrated. This indicates that the capacity of the WFD organization to support cross-sectoral decisions is low, even though we see some indications of increased integration within the WCs we have studied. Key decisions related to water are made outside of the WFD administration—by the municipalities through their planning monopoly, and within hydropower companies. One difference in Sweden compared to other European countries is the lack of regional-level decision making [47,48]. Based on this, the WCs have only two possibilities to influence water governance—through the development of stronger networks, or by applying for funding for water projects (2—understanding of collaboration and governance; 6—strategic use of networks). An increasing number of studies show several drawbacks of the reliance of networks for governing complex issues, including a lack of political mandate, unclear sharing of responsibility, and dependence of individual champions, as well as lack of transparency and accountability of decisions [79].

The interviews revealed that there is a close interconnection between the development of networks and the project funding structure, where most networks are created around funding and the funding even keeps the networks together. The projects mentioned were mainly related to ecology and water quality, reflecting the sector-wise funding for water projects (6—strategic use of networks; 3—interplay between public sectors; 4—integrating funding mechanisms). According to the respondents, the focus is on developing projects, i.e., implementing measures. That work is important and central to attain good water status. It is, however, also important to raise the question of who makes the strategic decisions? Our study reveals no such strategic level. Instead, the steering is decentralized in favor of the implementation of projects and specific measures, i.e., “projectification” [50]. This could potentially result in a situation where project funding is distributed inefficiently, based on who is more skilled in writing applications. This could result in more strategic issues being overlooked as well as a lack of transparency and balancing of values [80]. Networks, project financing and sector-wise regulation cannot replace long term strategic decisions related to value judgment where local and direct interests are considered together with national and long-term interests. Who carries the strategic mandate is not clear, and this situation resembles the situation for climate adaptation in Sweden [47] (6—strategic use of networks; 3—interplay between public sectors; 5—clarity of mandate; 4—integrating funding mechanisms).

To develop a well-functioning governance system characterized by participation and collaboration, nested within a layered system of representative democracy, is a grand and complicated task (7—consistency of governance system). Even in theory, the design of such a system is extremely challenging. Imagine the task planned for a complex governance practice, by water biology experts, and executed by staff without academic background in relevant fields (2—understanding of collaboration and governance). The CIS report on public participation can hardly make up for that knowledge discrepancy. Poorly developed participatory processes may be vulnerable to short-term and individual interests, inefficiency, social conflicts, trust being used up and the loss of future public engagement [81,82,83]. This study has revealed several positive effects of increased collaboration around water in relation to the WFD, such as the development towards more integration in the WCs compared to when they started, and stakeholder learning. We also have indications of problems, such as an overly narrow perspective on river management (flood issues mainly lacking), a lack of efficiency and the inability to handle strategic issues satisfactorily (network governance and projectification).

To sum up, water quality improvement and nature protection by the WFD are mainly implemented in Sweden as an add-on to other (more important?) societal issues—managed through informal networks and projects. Water quality and ecology are not integrated as parts of strategic development decisions regarding hydropower, municipal development or climate adaptation. It is unclear if this was the original intention, but it is clear that the rise in political attention brought on by the Weser court decision provides an opportunity to further develop the valuable participatory structures and expert knowledge built up, and to adopt the recommendations (below) to transform Swedish water governance into a system that can better support sustainable development.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations for Sweden

Here, the identified factors are listed together with our recommendations for the Swedish case which aid the understanding of the factors by serving as illustrative examples. Numbers refer to Table 4.

- Consistency of governance system (factor 7): To begin, governance of complex issues such as water needs to be designed carefully and comply with the overall (national) governance system. Studies have shown complications with the current Swedish setup, and that knowledge has not been sufficiently utilized. To achieve a transformation of Swedish water governance—and not use water ecology projects as “decoration” that may even drain resources from other environmental areas—Swedish water governance needs to be reconsidered as a whole. The current plan [55] does not solve the problems identified and discussed in this study. The interlinked steps listed below are recommended:

- Transparency of value trade-offs (factor 1): A fundamental component is the development of structures and processes for making transparent value trade-offs. It is therefore absolutely key to focus on the exceptions to the natural scientifically based objectives of the WFD. Clear and transparent structures and processes for how decisions about exceptions can be taken in an integrated and democratic way need to be designed. One possibility—that ensures a watershed perspective and makes use of developed participatory structures—is that WCs and river groups jointly suggest priorities, which thereafter are handled by the municipalities to ensure a democratic process.

- Clarity of mandate (5): Clarify mandates of different actors and between administrative scales. In Sweden, representative democratic power is mainly distributed at the national and local (municipal) scales. The WFD work, including the definition of binding objectives, rests heavily on the regional scale. We recommend that the regional level (CABs) should—in addition to their expert role—mainly play the role of process leaders, facilitating the linkage between national and local interests and scales. Such a division of mandate would resemble how the Flood Directive (FD) is implemented in Sweden. This would make much better use of, and improve, the national institutional system, which is in great need of regional coordination and process leadership.

- Interplay between public sectors (3): Management of the public sector division (3). To bridge public sectors involving water ecology/nature protection, flooding, hydropower, agriculture, drinking water, etc., there is a need for more integrated leadership at the regional scale (CABs; process leaders). By clarifying roles and mandates, existing networks at the local (WCs and RGs) and super local level (project groups) could have a more central role. This would aid integration of water-related issues. The WCs could for example bridge municipal jurisdictions, but they could also work more intimately with RGs and provide supporting material to the municipalities.

- Strategic use of networks (6): The development of well-functioning collaboration networks takes time. It involves the building of collaborative culture, and structures often have to be developed in a trial-and-error manner as they become stronger over time and interlinked with the overarching organization. It is therefore important to build on what has already been developed in the WCs, for example, their contacts with landowners, in the relicensing of hydropower. Give the collaborative structures time to mature and support them by assigning them clear and extended mandates.

- Understanding of collaboration and governance (2): Employ persons within the water administration that have a social science background related to governance and participation. The intense focus on the assessment of good status has created an unbalanced knowledge basis within the WFD organization. Practical experience/learning by doing is good, but it is not enough to build sustainable and integrated collaboration structures and to support and evaluate them over time. Specialist knowledge of cross-sectoral collaboration, participation and governance is needed to avoid the pitfalls of local participation.

- Integrating funding mechanisms (4): Development of financing models for environmental concern that span public sectors geared towards water management in a broad sense. Such models need to include mechanisms for strategic and transparent prioritization and coordination of national and EU funding. In addition to projects, funding of cross-sectoral organizational structures within the CABs is key.

Author Contributions

B.H. and J.A.-O. are likewise responsible for the study design, data collection, analysis and writing. L.G. has reviewed the study design and the interview guide and has assisted the analysis with a focus on river ecological aspects connected to the study, he has written the river cases sections of the paper and reviewed and edited the text as a whole and also facilitated the contacts with case actors due to his earlier research co-operation in the studied rivers. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Swedish Research Council for Environment Agricultural Sciences and Spatial Planning (grant number 2016-01432) and the Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency (Societal Resilience project).

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

This study is part of the research project “Collaborative processes as a recipe for sustainable river basin development? A study of Swedish water councils in three regulated rivers” (Dnr 2016-01432) funded by the Swedish research council for sustainable development, FORMAS, and of the project “Societal Resilience”, funded by the Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency, MSB. We would also like to thank our respondents who contributed to the study with their valuable time. Lastly, we thank Maria Söderberg för her assistance with test interviews.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Miller, T.R. Constructing sustainability science: Emerging perspectives and research trajectories. Sustain. Sci. 2013, 8, 279–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, A. The governance of sustainable development: Taking stock and looking forwards. Environ. Plan. C-Gov. Policy 2008, 26, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFries, R.; Nagendra, H. Ecosystem management as a wicked problem. Science 2017, 356, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedelin, B. Complexity is no excuse: Introduction of a research model for turning sustainable development from theory into practice. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 733–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, A.; Lenschow, A. Policy paper environmental policy integration: A state of the art review. Environ. Policy Gov. 2010, 20, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bryan, T.A. Tragedy averted: The promise of collaboration. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2004, 17, 881–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, P. Collaborative Planning in perspective. Plan. Theory 2003, 2, 101–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, C.; Gash, A. Collaborative governance in theory and practice. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2008, 18, 543–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margerum, R.D. Beyond Consensus: Improving Collaborative Planning and Management; Mit Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; pp. 1–395.

- Foster-Fishman, P.G.; Berkowitz, S.L.; Lounsbury, D.W.; Jacobson, S.; Allen, N.A. Building Collaborative Capacity in Community Coalitions: A Review and Integrative Framework. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2001, 29, 241–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feist, A.; Plummer, R.; Baird, J. The Inner-Workings of Collaboration in Environmental Management and Governance: A Systematic Mapping Review. Environ. Manag. 2020, 66, 801–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, D. Governance and the commons in a multi-level world. Int. J. Commons 2008, 2, 7–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoon, M.; Cox, M.E. Collaboration, adaptation, and scaling: Perspectives on environmental governance for sustainability. Sustainability 2018, 10, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newig, J.; Fritsch, O. Environmental governance: Participatory, multi-level—And effective? Environ. Policy Gov. 2009, 19, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananda, J.; Proctor, W. Collaborative approaches to water management and planning: An institutional perspective. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 86, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prager, K. Local and regional partnerships in natural resource management: The challenge of bridging institutional levels. Environ. Manag. 2010, 46, 711–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amsler, L.B. Collaborative Governance: Integrating Management, Politics, and Law. Public Adm. Rev. 2016, 76, 700–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conley, A.; Moote, M.A. Evaluating collaborative natural resource management. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2003, 16, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frame, T.M.; Gunton, T.; Day, J.C. The role of collaboration in environmental management: An evaluation of land and resource planning in British Columbia. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2004, 47, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, T.; Ostrom, E.; Stern, P.C. The Struggle to Govern the Commons. Science 2003, 302, 1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahl-Wostl, C. A conceptual framework for analysing adaptive capacity and multi-level learning processes in resource governance regimes. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2009, 19, 354–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C.; Hahn, T.; Olsson, P.; Norberg, J. Adaptive Governance of Social-Ecological Systems. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2005, 30, 441–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brondizio, E.S.; Ostrom, E.; Young, O.R. Connectivity and the Governance of Multilevel Social-Ecological Systems: The Role of Social Capital. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2009, 34, 253–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, K.; Nabatchi, T.; Balogh, S. An Integrative Framework for Collaborative Governance. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2012, 22, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpouzoglou, T.; Dewulf, A.; Clark, J. Advancing adaptive governance of social-ecological systems through theoretical multiplicity. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 57, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.; Dahya, J. The competent boundary spanner. Public Adm. 2002, 80, 103–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.; Cochrane, A. Beyond the territorial fix: Regional assemblages, politics and power. Reg. Stud. 2007, 41, 1161–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smajgl, A.; Ward, J.R.; Foran, T.; Dore, J.; Larson, S. Visions, beliefs, and transformation: Exploring cross-sector and transboundary dynamics in the wider Mekong region. Ecol. Soc. 2015, 20, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedelin, B. Further development of a sustainable procedure framework for strategic natural resources and disaster risk management. J. Nat. Resour. Policy Res. 2015, 7, 247–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J. Squaring the circle? Some thoughts on the idea of sustainable development. Ecol. Econ. 2004, 48, 369–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawhney, P.; Kobayashi, M.; Takahashi, M.; King, P.N.; Mori, H. Participation of Civil Society in Management of Natural Resources. Int. Rev. Environ. Strateg. 2007, 7, 117–131. [Google Scholar]

- Hedelin, B. Criteria for the assessment of sustainable water management. Environ. Manag. 2007, 39, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Biswas, A.K. Integrated water resources management: Is it working? Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2008, 24, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Crossman, N.D.; Nolan, M.; Ghirmay, H. Bringing ecosystem services into integrated water resources management. J. Environ. Manag. 2013, 129, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graversgaard, M.; Hedelin, B.; Smith, L.; Gertz, F.; Højberg, A.L.; Langford, J.; Martinez, G.; Mostert, E.; Ptak, E.; Peterson, H.; et al. Opportunities and barriers for water co-governance: A critical analysis of seven cases of diffuse water pollution from agriculture in Europe, Australia and North America. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU. Directive 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2000 Establishing a Framework for Community Action in the Field of Water Policy. Off. J. 2000, 5, 1–72. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/policy-documents/directive-2000-60-ec-of (accessed on 7 March 2023).

- EU. Directive 2007/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2007 on the Assessment and Management of Flood Risks. Off. J. Eur. Union 2007, 27–34. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/policy-documents/directive-2007-60-ec-of (accessed on 7 March 2023).

- Koontz, T.M.; Newig, J. Cross-level information and influence in mandated participatory planning: Alternative pathways to sustainable water management in Germany’s implementation of the EU Water Framework Directive. Land Use Policy 2014, 38, 594–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jupner, R.; Muller, U. Who is doing what? Division of Labour in the Implementation Process of the EU Flood Risk Management Directive. Wasserwirtschaft 2010, 100, 47–50. [Google Scholar]

- Earle, J.R.; Blacklocke, S.; Bruen, M.; Almeida, G.; Keating, D. Integrating the implementation of the European Union Water Framework Directive and Floods Directive in Ireland. Water Sci. Technol. 2011, 64, 2044–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jager, N.W.; Challies, E.; Kochskämper, E.; Newig, J.; Benson, D.; Blackstock, K.; Collins, K.; Ernst, A.; Evers, M.; Feichtinger, J.; et al. Transforming European water governance? Participation and river basin management under the EU water framework directive in 13 member states. Water 2016, 8, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovik, S.; Hanssen, G.S. Implementing the EU Water Framework Directive in Norway: Bridging the Gap Between Water Management Networks and Elected Councils? J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2016, 18, 535–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, M.; Balfors, B.; Mörtberg, U.; Petersson, M.; Quin, A. Governance of water resources in the phase of change: A case study of the implementation of the EU Water Framework Directive in Sweden. Ambio 2011, 40, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjärstig, T.; Thellbro, C.; Stjernström, O.; Svensson, J.; Sandström, C.; Sandström, P.; Zachrisson, A. Between protocol and reality: Swedish municipal comprehensive planning. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2018, 26, 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundqvist, L.J.; von Borgstede, C. Whose responsibility?: Swedish local decision makers and the scale of climate change abatement. Urban Aff. Rev. 2008, 43, 299–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadowcroft, J. Who is in Charge here? Governance for Sustainable Development in a Complex World*. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2007, 9, 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koglin, T.; Pettersson, F. Changes, Problems, and Challenges in Swedish Spatial Planning—An Analysis of Power Dynamics. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granberg, M.; Elander, I.; Montin, S. Between the Regulatory State and the Networked Polity: Central-Local Government Relations in Sweden. Center for Open Science, 2021. Available online: https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/a2stn (accessed on 7 March 2023).

- Lundqvist, L.J. Integrating Swedish water resource management: A multi-level governance trilemma. Local Environ. 2004, 9, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedelin, B. The EU Floods Directive trickling down: Tracing the ideas of integrated and participatory flood risk management in Sweden. Water Policy 2017, 19, 286–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prutzer, M.; Sonery, L. Samverkan Och Deltagande i Vattenråd och Vattenförvaltning; 2016:35; Havs- och vattenmyndigheten: Göteborg, Sweden, 2016; p. 54. [Google Scholar]

- Sölve, T.W.; Molin, O. SOU 1995:40, Älvsäkerhet. 1995. SOU 1995:40. Available online: https://filedn.com/ljdBas5OJsrLJOq6KhtBYC4/forarbeten/sou/1995/sou-1995-40.pdf (accessed on 7 March 2023).

- Ardesjö Lundén, K. SOU 2019:66, En utvecklad vattenförvaltning. 2019, 1 och 2. Available online: https://www.regeringen.se/rattsliga-dokument/statens-offentliga-utredningar/2019/12/sou-201966/ (accessed on 7 March 2023).

- Lindholm, K. Vattenkraftsproduktion. Available online: https://www.energiforetagen.se/energifakta/elsystemet/produktion/vattenkraft/vattenkraftsproduktion/ (accessed on 7 March 2023).

- Calles, O.; Greenberg, L. Connectivity is a two-way street: The need for a holistic approach to fish passage problems in regulated rivers. River Res. Appl. 2009, 25, 1268–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendz, A.; Boholm, Å. Indispensable, yet Invisible: Drinking water management as a local political issue in Swedish municipalities. Local Gov. Stud. 2020, 46, 800–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arheimer, B.; Lindström, G. Climate impact on floods: Changes in high flows in Sweden in the past and the future (1911–2100). Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2015, 19, 771–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannaford, J.; Buys, G.; Stahl, K.; Tallaksen, L.M. The influence of decadal-scale variability on trends in long European streamflow records. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2013, 17, 2717–2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]