The Impact of AfCFTA on Welfare and Trade: Nigeria and South Africa in Light of Core Export Competences

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Underpinnings

2.2. Empirical Understandings

2.3. Nigeria and South Africa’s Trade Liberalisation Efforts

3. Research Method

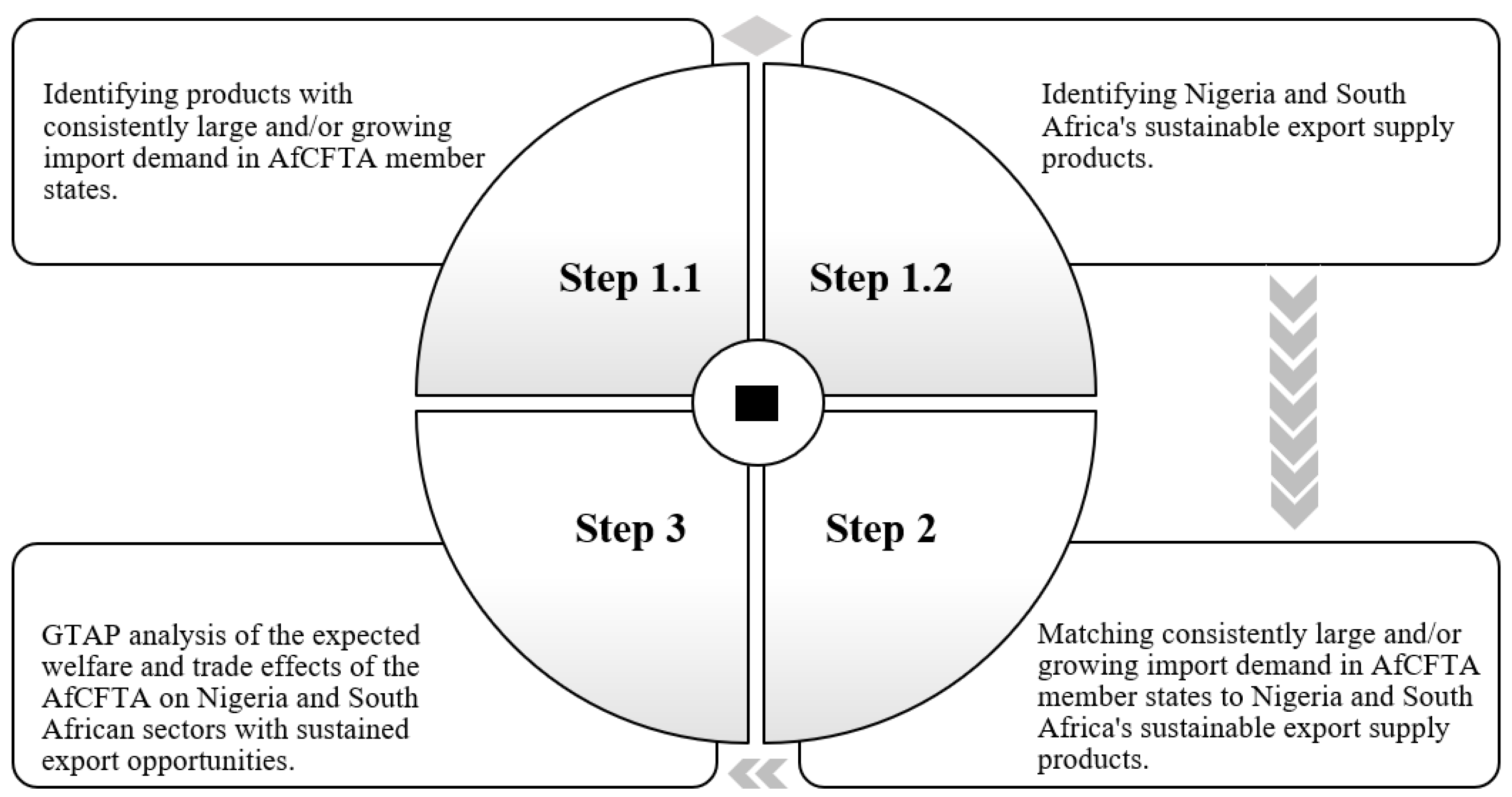

3.1. Empirical Strategy

3.2. Data Analysis

3.2.1. Step 1.1

3.2.2. Step 1.2

3.2.3. Step 2

3.2.4. Step 3

- Scenario 1:

- full elimination of the AfCFTA_24 (i.e., AfCFTA members with sustained import demand for Nigeria) import tariffs on all matched sustainable exports originating from Nigeria, and full elimination of Nigeria’s export subsidies on all its matched sustainable exports to the AfCFTA_24; and

- Scenario 2:

- full elimination of the AfCFTA_37 (i.e., AfCFTA members with sustained import demand for South Africa) import tariffs on all matched sustainable exports originating from South Africa and full elimination of South Africa’s export subsidies on all its matched sustainable exports to the AfCFTA_37.

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. Sustained Export Opportunities for Nigeria and South Africa in the AfCFTA

4.2. Welfare Effects of the AfCFTA under the Two Scenarios

4.3. Trade Creation and Diversion of the AfCFTA under the Two Scenarios

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- African Union. Agenda 2063: The Africa We Want. 2013. Available online: https://au.int/en/agenda2063/overview (accessed on 28 January 2019).

- Trade Law Centre. Status of AfCFTA Ratification. 2019. Available online: https://www.tralac.org/resources/infographic/13795-status-of-afcfta-ratification.html (accessed on 12 February 2019).

- Erasmus, G. The AfCFTA: What has Been Achieved and When will it Become Operational? 2018. Available online: https://www.tralac.org/publications/article/13134-the-afcfta-what-has-been-achieved-and-when-will-it-become-operational.html (accessed on 19 August 2019).

- African Union. Summary of the Key Decisions and Declarations of the 31st African Union Summit. 2018. Available online: https://au.int/en/pressreleases/20180706/summary-key-decisions-and-declarations-31st-african-union-summit (accessed on 12 February 2019).

- United Nations Economic Commission for Africa. African Continental Free Trade Area. 2018. Available online: https://au.int/sites/default/files/documents/33984-doc-qa_cfta_en_rev15march.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2019).

- United Nations Economic Commission for Africa. Building a Sustainable and Inclusive Continental Free Trade Area. 2017. Available online: https://www.uneca.org/sites/default/files/PublicationFiles/policy_brief_building_sustainable_and_inclusive.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2019).

- United Nations Economic Commission for Africa. Assessing Regional Integration in Africa VIII: Bringing the CFTA About; United Nations: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. World Development Indicators. 2022. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=ZG (accessed on 20 November 2019).

- Saygili, M.; Peters, R.; Knebel, C. African Continental Free Trade Area: Challenges and Opportunities of Tariff Reductions; UNCTAD Publishing: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Abrego, M.L.; Amado, M.A.; Gursoy, T.; Nicholls, G.P.; Perez-Saiz, H. The African Continental Free Trade Agreement: Welfare Gains Estimates from a General Equilibrium Model; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zidouemba, P.R.; Jallab, M.S. The African Continental Free Trade Area and the trade facilitation agreement: Some regional macroeconomic impacts. Int. J. Trade Glob. Mark. 2021, 14, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengoa, M.; Mathur, S.; Narayanan, B.; Norberg, H.C. Environmental Effects of the African Continental Free Trade Agreement: A Computable General Equilibrium Model Approach. J. Afr. Trade 2021, 8, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyelami, L.O. Revenue, welfare and trade effects of African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AFCFTA) on Nigerian economy. J. Public Aff. 2021, 22, e2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayale, N.; Ibrahim, M.; Atta-Mensah, J. Potential trade, welfare and revenue implications of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) for Ghana: An application of partial equilibrium model. J. Public Aff. 2020, 22, e2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, T.; Zignago, S. Market Access in Global and Regional Trade; CEPII: Paris, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- World Trade Organization. Regional Trade Agreements and Preferential Trade Arrangements. 2017. Available online: https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/region_e/rta_pta_e.htm (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Moser, C.; Rose, A.K. Who benefits from regional trade agreements? The view from the stock market. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2014, 68, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Songwe, V. Intra-African Trade: A Path to Economic Diversification and Inclusion; The Brookings Institution: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Nollen, S.D.; Quinn, D.P. Free trade, fair trade, strategic trade, and protectionism in the US Congress, 1987–1988. Int. Organ. 1994, 48, 491–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Whalley, J. Trade protectionism and US manufacturing employment. Econ. Model. 2020, 96, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaldor, N. The foundations of free trade theory and their implications for the current world recession. In Unemployment in Western Countries; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 1980; pp. 85–100. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations; Methuen and Company: London, UK, 1776. [Google Scholar]

- Ricardo, D. The Principles of Political Economy and Taxation; G. Bell and Sons: London, UK, 1817. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, R.W. Factor Proportions and the Heckscher-Ohlin Theorem. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1956, 24, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leamer, E.E.; Levinsohn, J. International trade theory: The evidence. Handb. Int. Econ. 1995, 3, 1339–1394. [Google Scholar]

- Chipman, J.S. Factor price equalisation and the Stolper-Samuelson theorem. Int. Econ. Rev. 1969, 10, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvatore, D. International Economics, 8th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rahim, S. What use is the Neo-Classical Theory of International Trade? Lahore J. Econ. 1999, 4, 89–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhonyera, G.; Steenkamp, E.A.; Matthee, M. Evaluating South Africa’s utilisation of sustained export potential in sub-Saharan Africa. S. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2018, 21, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Myerson, R.B. Game Theory; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Straffin, P.D. Game Theory and Strategy; Mathematical Association of America: Washington, DC, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Abbott, K.W. The trading nation’s dilemma: The functions of the law of international trade. Harv. Int. Law J. 1985, 26, 501–532. [Google Scholar]

- Dawes, R.M.; McTavish, J.; Shaklee, H. Behaviour, communication, and assumptions about other people’s behaviour in a commons dilemma situation. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1977, 35, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, C.A.; Capra, M. Classroom games: A prisoner’s dilemma. J. Econ. Educ. 2000, 31, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, A.E.; Murnighan, J.K. Equilibrium behaviour and repeated play of the prisoner’s dilemma. J. Math. Psychol. 1978, 17, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sykes, A.O. Regulatory Protectionism and the Law of International Trade. Univ. Chic. Law Rev. 1999, 66, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrik, D. Has globalisation gone too far? Challenge 1998, 41, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kee, H.L.; Neagu, C.; Nicita, A. Is Protectionism on the Rise? Assessing National Trade Policies during the Crisis of 2008. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2013, 95, 342–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Milner, H.V. Resisting Protectionism: Global Industries and the Politics of International Trade; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Cernat, L. Assessing regional trade arrangements: Are South-South RTAs more trade diverting. Glob. Econ. Q. 2001, 2, 235–259. [Google Scholar]

- Caliendo, L.; Parro, F. Estimates of the Trade and Welfare Effects of NAFTA. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2014, 82, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Timsina, K.P.; Culas, R.J. Australia’s Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) and Potentiality of Wheat Exports: A Panel Gravity Model Approach. J. East-West Bus. 2021, 28, 61–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustilli, F. Estimating the economic gains of TTIP. Intereconomics 2015, 50, 321–327. [Google Scholar]

- Timini, J.; Viani, F. A highway across the Atlantic? Trade and welfare effects of the EU-Mercosur agreement. Int. Econ. 2022, 169, 291–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makochekanwa, A. Welfare Implications of COMESA-EAC-SADC Tripartite Free Trade Area. Afr. Dev. Rev. 2014, 26, 186–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagdambe, S.; Mouzam, S.M. Evaluating the trade, revenue and welfare implication of plantation crops under ASEAN-India FTA. J. Asian Econ. Integr. 2019, 1, 224–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biden, S.; Ker, A.P.; Duff, S. Impacts of trade liberalisation in Canada’s supply managed dairy industry. Agric. Econ. 2020, 51, 535–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertel, T.W.; Walmsley, T.; Itakura, K. Dynamic Effects of the "New Age" Free Trade Agreement between Japan and Singapore. J. Econ. Integr. 2001, 16, 446–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Siriwardana, M.; Yang, J. GTAP Model Analysis of the Economic Effects of an Australia–China FTA: Welfare and Sectoral Aspects. Glob. Econ. Rev. 2008, 37, 341–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.-W.; Yoon, G. Sectoral analysis of an Australia–India free trade agreement. J. Asia Pac. Econ. 2014, 19, 205–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, C.; Shah, S.Z.A. Quantitative assessment of Pakistan and China free trade agreement. Pak. J. Commer. Soc. Sci. 2017, 11, 293–308. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, D.; Chen, Z.; Rose, A. Estimating economic impacts of the US-South Korea free trade agreement. Econ. Syst. Res. 2019, 31, 305–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, I. East Asian regional trade agreements: Do they promote global free trade? Pac. Econ. Rev. 2006, 11, 547–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Itakura, K. The welfare and sectoral adjustment effects of mega-regional trade agreements on ASEAN countries. J. Asian Econ. 2018, 55, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Burfisher, M.E.; Lambert, F.; Matheson, M.T.D. NAFTA to USMCA: What is Gained? International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Siriwardana, M. An Analysis of the Impact of Indo-Lanka Free Trade Agreement and Its Implications for Free Trade in South Asia. J. Econ. Integr. 2004, 19, 568–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- International Trade Centre. List of Importers for the Selected Product in 2021: Total All Products. 2022. Available online: https://www.trademap.org/Country_SelProduct.aspx?nvpm (accessed on 9 June 2022).

- South Africa, Department of Trade and Industry. Trade, Exports and Investment. 2017. Available online: https://www.thedti.gov.za/trade_investment/ited_trade_agreement.jsp (accessed on 20 November 2019).

- South Africa, Industrial Development Corporation. Export Opportunities for SOUTH Africa in Selected African Countries. 2014. Available online: http://www.idc.co.za/home/financial-results/research-reports.html (accessed on 16 October 2019).

- South Africa, Department of Trade and Industry. Memorandum. 2018. Available online: https://www.thedti.gov.za/parliament/2018/TFTA%20_COMESA_EAC_SADC.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2019).

- Cuyvers, L.; De Pelsmacker, P.; Rayp, G.; Roozen, I.T.M. A decision support model for the planning and assessment of export promotion activities by government export promotion institutions: The Belgian case. Int. J. Res. Mark. 1995, 12, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuyvers, L.; Viviers, W. Export Promotion: A Decision Support Model Approach; African Sun Media: Stellenbosch, South Africa, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hertel, T.W. Global Trade Analysis: Modeling and Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Cuyvers, L. Identifying export opportunities: The case of Thailand. Int. Mark. Rev. 2004, 21, 255–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willemé, P.; Van Steerteghem, D. Een Normatief Model Voor de Planning van Export-Bevorderende Activiteiten van de Vlaamse Dienst voor de Buitenlandse Handel. Unpublished work. 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Balassa, B. Trade Liberalisation and Revealed Comparative Advantage; Yale University Growth Centre: New Haven, CT, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Reis, J.G.; Farole, T. The Trade Competitiveness Diagnostics Toolkit; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mhonyera, G. Identifying Priority Products and Sectors for Bilateral Trade Negotiations: The Case of AGOA beyond 2025. Ph.D. Thesis, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Vollrath, T.L. A theoretical evaluation of alternative trade intensity measures of revealed comparative advantage. Rev. World Econ. 1991, 127, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armington, P.S. A Theory of Demand for Products Distinguished by Place of Production. Staff. Pap. Int. Monet. Fund 1969, 16, 159–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, A.; Chepeliev, M.; Corong, E.L.; McDougall, R.; Van Der Mensbrugghe, D. The GTAP Data Base: Version 10. J. Glob. Econ. Anal. 2019, 4, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Burfisher, M.E. Introduction to Computable General Equilibrium Models; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Viner, J. The Customs Union Issue; Carnegie Endowment for International Peace: New York, NY, USA, 1950. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Classification | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| Short-term import market growth | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Long-term import market growth | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Relative import market size | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Nigeria | Total | |

| Step 1.1 | Product–country combinations identified with consistently large and/or growing import demand in the AfCFTA from 2014 to 2018 | 494 |

| Step 1.2 | Products consistently competitively exported by Nigeria (i.e., sustainable exports selected in Step 1.2, with RCA > 0.7 and RTA > 0 from 2014 to 2018) | 320 |

| Step 2 | Product–country combinations identified with consistently large and/or growing import demand in the AfCFTA from 2014 to 2018, matching Nigeria’s sustainable exports | 61 |

| South Africa | Total | |

| Step 1.1 | Product–country combinations identified with consistently large and/or growing import demand in the AfCFTA from 2014 to 2018 | 725 |

| Step 1.2 | Products consistently competitively exported by South Africa (i.e., sustainable exports selected in Step 1.2, with RCA > 0.7 and RTA > 0 in 2014 to 2018) | 559 |

| Step 2 | Product–country combinations identified with consistently large and/or growing import demand in the AfCFTA from 2014 to 2018 matching South Africa’s sustainable exports | 145 |

| Allocative Efficiency Effect | Endowment Effect | Terms of Trade Effect | Investment-Savings Effect | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario 1 | |||||

| Nigeria | 27.77 | 53.53 | 80.49 | −15.66 | 146.12 |

| AfCFTA_24 | 23.47 | 110.16 | −33.51 | −7.02 | 93.10 |

| Rest of AfCFTA | −0.78 | 0.03 | −0.43 | 0.07 | −1.11 |

| Rest of World | −9.02 | 0.00 | −46.58 | 22.61 | −32.99 |

| Total (World) | 41.44 | 163.72 | −0.03 | 0.01 | 205.13 |

| Scenario 2 | |||||

| South Africa | 685.89 | 911.24 | −132.14 | −5.92 | 1459.07 |

| AfCFTA_37 | −26.00 | 1255.95 | 558.81 | −65.21 | 1723.54 |

| Rest of AfCFTA | −2.38 | −2.20 | 10.65 | 0.26 | 6.33 |

| Rest of World | −273.54 | 0.00 | −436.84 | 70.87 | −639.50 |

| Total (World) | 383.97 | 2164.99 | 0.48 | 0.00 | 2549.45 |

| Sector | Change in Real AfCFTA_24 Imports from Nigeria | Change in Real AfCFTA_24 Imports from Other Regions |

|---|---|---|

| Animal products not elsewhere specified | 0.00 | −0.04 |

| Beverages and tobacco products | 58.04 | −18.83 |

| Bovine cattle, sheep and goats | 0.00 | −0.06 |

| Bovine meat products | 0.01 | −0.61 |

| Chemical products | 83.69 | −62.62 |

| Crops not elsewhere specified | 6.74 | −3.24 |

| Ferrous metals | 6.02 | −3.61 |

| Food products not elsewhere specified | 72.86 | −33.10 |

| Forestry | 0.07 | −0.02 |

| Leather products | 125.79 | −78.28 |

| Manufactures not elsewhere specified | 15.47 | −10.49 |

| Metal products | 8.24 | −6.04 |

| Metals not elsewhere specified | 24.21 | −16.38 |

| Oil seeds | 1.18 | −1.13 |

| Petroleum, coal products | 16.03 | −8.09 |

| Processed rice | 0.29 | −0.73 |

| Sugar | 0.24 | −0.99 |

| Textiles | 199.87 | −135.38 |

| Vegetable oils and fats | 0.40 | −1.94 |

| Vegetables, fruit, nuts | 0.82 | −0.88 |

| Total | 619.97 | −382.46 |

| Sector | Change in Real AfCFTA_37 Imports from South Africa | Change in Real AfCFTA_37 Imports from Other Regions |

|---|---|---|

| Beverages and tobacco products | 64.74 | −17.07 |

| Chemical products | 530.37 | −390.93 |

| Crops not elsewhere specified | 1.66 | −0.99 |

| Dairy products | 44.77 | −24.97 |

| Ferrous metals | 84.77 | −75.00 |

| Fishing | 0.10 | 0.30 |

| Food products not elsewhere specified | 164.22 | −66.82 |

| Forestry | −0.54 | 0.39 |

| Machinery and equipment not elsewhere specified | 1152.19 | −893.32 |

| Manufactures not elsewhere specified | 150.13 | −86.50 |

| Metal products | 274.55 | −166.54 |

| Metals not elsewhere specified | 10.10 | −8.93 |

| Mineral products not elsewhere specified | 31.35 | −16.50 |

| Minerals not elsewhere specified | 0.34 | 7.35 |

| Motor vehicles and parts | 999.13 | −727.86 |

| Oil | 0.00 | −41.37 |

| Paper products, publishing | 151.96 | −98.24 |

| Petroleum, coal products | 1800.89 | −1175.18 |

| Rubber and plastic products | 181.82 | −126.38 |

| Textiles | 101.46 | −57.22 |

| Vegetable oils and fats | 14.63 | −9.70 |

| Vegetables, fruit, nuts | 114.88 | −41.51 |

| Wearing apparel | 88.96 | −41.43 |

| Wood products | 18.64 | −10.51 |

| Wool, silk-worm cocoons | 2.96 | −1.90 |

| Total | 5984.08 | −4070.83 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mhonyera, G.; Meyer, D.F. The Impact of AfCFTA on Welfare and Trade: Nigeria and South Africa in Light of Core Export Competences. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5090. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065090

Mhonyera G, Meyer DF. The Impact of AfCFTA on Welfare and Trade: Nigeria and South Africa in Light of Core Export Competences. Sustainability. 2023; 15(6):5090. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065090

Chicago/Turabian StyleMhonyera, Gabriel, and Daniel Francois Meyer. 2023. "The Impact of AfCFTA on Welfare and Trade: Nigeria and South Africa in Light of Core Export Competences" Sustainability 15, no. 6: 5090. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065090