Cultural Heritage Topics in Online Queries: A Comparison between English- and Polish-Speaking Internet Users

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Language as Cultural Heritage

2.2. Introduction to Polish Research on Verbal Communication on the Internet

2.3. English as a Dominant Language

2.4. Cultural Heritage on the Internet

2.5. Keyword Analyses

2.6. The Information Potential of Keywords

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. The Research Approach

3.2. Conclusion Mechanisms and Data Analysis

3.3. Research Tools

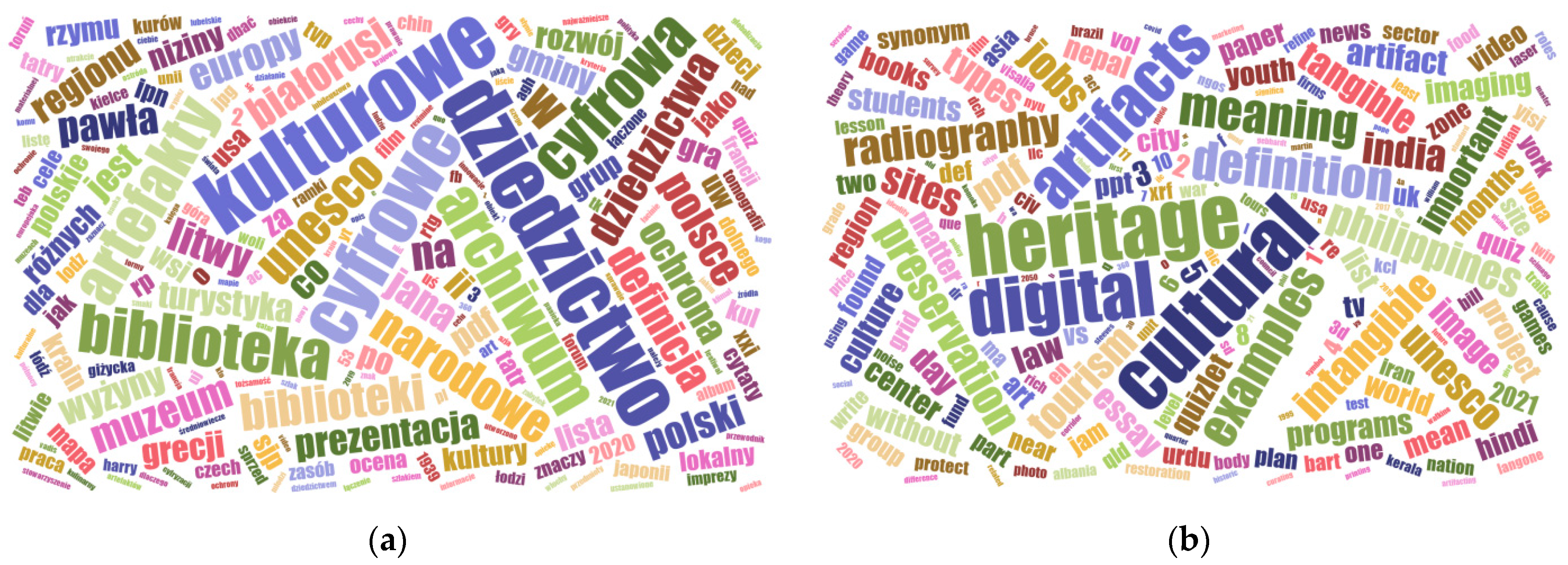

4. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. The Many Sides of Keyword Analysis

5.2. Search Query Data for Analysing Tourists’ Online Search Behaviour

5.3. Cultural Heritage in Online Queries

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Practical Implications

6.3. Limitations of the Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Munjeri, D. Tangible and Intangible Heritage: From Difference to Convergence. Mus. Int. 2004, 56, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowenthal, D. Natural and Cultural Heritage. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2005, 11, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Król, K.; Zdonek, D. Initiatives to Preserve the Content of Vanishing Web Hosting. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecco, M. A Definition of Cultural Heritage: From the Tangible to the Intangible. J. Cult. Herit. 2010, 11, 321–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thwaites, H. Digital Heritage: What Happens When We Digitize Everything? In Visual Heritage in the Digital Age; Ch’ng, E., Gaffney, V., Chapman, H., Eds.; Springer: London, UK, 2013; pp. 327–348. ISBN 978-1-4471-5534-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, H.; Ruggles, D.F. Cultural Heritage and Human Rights. In Cultural Heritage and Human Rights; Silverman, H., Ruggles, D.F., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 3–29. ISBN 978-0-387-71312-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, T.H.; Navrud, S. Capturing the Benefits of Preserving Cultural Heritage. J. Cult. Herit. 2008, 9, 326–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowitz, E.; Ibenholt, K. Economic Impacts of Cultural Heritage—Research and Perspectives. J. Cult. Herit. 2009, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiktor-Mach, D. Cultural Heritage and Development: UNESCO’s New Paradigm in a Changing Geopolitical Context. Third World Q. 2019, 40, 1593–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Król, K. Assessment of the Cultural Heritage Potential in Poland. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruijgrok, E.C.M. The Three Economic Values of Cultural Heritage: A Case Study in the Netherlands. J. Cult. Herit. 2006, 7, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, M.; Pozzi, F. Towards a New Era for Cultural Heritage Education: Discussing the Role of ICT. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011, 27, 1365–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addis, M. New Technologies and Cultural Consumption—Edutainment Is Born! Eur. J. Mark. 2005, 39, 729–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Oliva, A.; Alvarado-Uribe, J.; Parra-Meroño, M.C.; Jara, A.J. Transforming Communication Channels to the Co-Creation and Diffusion of Intangible Heritage in Smart Tourism Destination: Creation and Testing in Ceutí (Spain). Sustainability 2019, 11, 3848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Camacho, D.; Jung, J.E. Identifying and Ranking Cultural Heritage Resources on Geotagged Social Media for Smart Cultural Tourism Services. Pers Ubiquit Comput 2017, 21, 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassiliadis, C.; Belenioti, Z.-C. Museums & Cultural Heritage via Social Media: An Integrated Literature Review. Tourismos 2017, 12, 97–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.F.; Pettijohn, J.B. Using Keyword Research Software to Assist in the Search for High-Demand, Low-Supply Online Niches: An Overview. J. Internet Commer. 2008, 6, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, A.; Motwani, R. Keyword Generation for Search Engine Advertising. In Sixth IEEE International Conference on Data Mining—Workshops (ICDMW’06); IEEE: Hong Kong, China, 2006; pp. 490–496. ISBN 978-0-7695-2702-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scholz, M.; Brenner, C.; Hinz, O. AKEGIS: Automatic Keyword Generation for Sponsored Search Advertising in Online Retailing. Decis. Support Syst. 2019, 119, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallis, R.; Isaac, A.; Charles, V.; Manguinhas, H. Recommendations for the Application of Schema. Org to Aggregated Cultural Heritage Metadata to Increase Relevance and Visibility to Search Engines: The Case of Europeana. Code4Lib J. 2017, 36. Available online: https://journal.code4lib.org/articles/12330 (accessed on 11 December 2022).

- Podara, A.; Giomelakis, D.; Nicolaou, C.; Matsiola, M.; Kotsakis, R. Digital Storytelling in Cultural Heritage: Audience Engagement in the Interactive Documentary New Life. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortells, R.; Egozcue, J.; Ortego, M.; Garola, A. Relationship between the Popularity of Key Words in the Google Browser and the Evolution of Worldwide Financial Indices. In Compositional Data Analysis. CoDaWork 2015. Springer Proceedings in Mathematics & Statistics; Martín-Fernández, J., Thió-Henestrosa, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 187, pp. 145–165. ISBN 978-3-319-44811-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, T. Text Mining. In Studies in Big Data; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 45, ISBN 978-3-319-91815-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- vanden Broucke, S.; Baesens, B. Practical Web Scraping for Data Science; Apress: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-1-4842-3582-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Zha, S.; Li, L. Social Media Competitive Analysis and Text Mining: A Case Study in the Pizza Industry. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2013, 33, 464–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müngen, A.A. Personalised Publication Recommendation Service for Open-Access Digital Archives. J. Inf. Sci. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Chen-Chuan-Chang, K. Editorial: Special Issue on Web Content Mining. ACM SIGKDD Explor. Newsl. 2004, 6, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, R.; Katona, Z. The Role of Search Engine Optimization in Search Marketing. Mark. Sci. 2013, 32, 644–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guzman, J.; Poblete, B. On-Line Relevant Anomaly Detection in the Twitter Stream: An Efficient Bursty Keyword Detection Model. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGKDD Workshop on Outlier Detection and Description; ACM: Chicago, IL, USA, 2013; pp. 31–39. ISBN 978-1-4503-2335-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griswold, W. A Methodological Framework for the Sociology of Culture. Sociol. Methodol. 1987, 17, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Król, K.; Hernik, J. Digital Folklore of Rural Tourism in Poland. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orellana, M.F.; Martínez, D.C.; Lee, C.H.; Montaño, E. Language as a Tool in Diverse Forms of Learning. Linguist. Educ. 2012, 23, 373–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steels, L. Experiments on the Emergence of Human Communication. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2006, 10, 347–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walczak, B. Język Polski Jako Nośnik Kultury Europejskiej. Polonistyka 2003, 6, 324–328. [Google Scholar]

- Walczak, B. Język Wobec Procesów Globalizacji. Ann. Univ. Paedagog. Cracoviensis. Stud. Linguist. 2011, 6, 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- Miodunka, W. Polszczyzna Jako Język Drugi: Definicja Języka Drugiego. In Silva rerum philologicarum. Studia ofiarowane Profesor Marii Strycharskiej-Brzezinie z okazji Jej jubileuszu; Gruchała, J.S., Kurek, H., Eds.; Wydawnictwo Księgarnia Akademicka: Kraków, Polska, 2010; pp. 233–245. [Google Scholar]

- Ligara, B. Relacje Między Językiem Ogólnym a Językiem Specjalistycznym w Perspektywie Językoznawstwa Polonistycznego, Stosowanego i Glottodydaktyki. LingVaria 2011, 2, 163–181. [Google Scholar]

- Frauenfelder, M.; Bates, R. The World of Raspberry Pi Retro Gaming. In Raspberry Pi Retro Gaming; Apress: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2019; pp. 1–23. ISBN 978-1-4842-5152-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kita, M. Językoznawcy Wobec Badań Języka w Internecie. Artes Hum. 2016, 1, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajda, S. Promocja Języka i Kultury Polskiej a Procesy Uniwersalizacji i Nacjonalizacji Kulturowo-Językowej w Świecie. In Promocja Języka i Kultury Polskiej w Świecie; Mazur, J., Ed.; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Marii Curie-Skłodowskiej: Lublin, Polska, 1998; pp. 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Seweryn, A. Dominacja Języka Angielskiego We Współczesnej Komunikacji Naukowej–Bariera Czy Usprawnienie Cyrkulacji Informacji Naukowej. In Zarządzanie Informacją w Nauce; Pietruch-Reizes, D., Babik, W., Frączek, R., Eds.; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego: Katowice, Polska, 2010; pp. 75–93. [Google Scholar]

- Hamel, R.E. The Dominance of English in the International Scientific Periodical Literature and the Future of Language Use in Science. Aila Rev. 2007, 20, 53–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, G.; Pérez-Llantada, C.; Plo, R. English as an International Language of Scientific Publication: A Study of Attitudes: English as an International Language of Scientific Publication. World Engl. 2011, 30, 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, I.K. English for Special Purposes: Specialized Languages and Problems of Terminology. Acta Univ. Sapientiae Philol. 2014, 6, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Król, K.; Zdonek, D. Digital Assets in the Eyes of Generation Z: Perceptions, Outlooks, Concerns. JRFM 2022, 16, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyvönen, E. Semantic Portals for Cultural Heritage. In Handbook on Ontologies; Staab, S., Studer, R., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 757–778. ISBN 978-3-540-70999-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Machidon, O.-M.; Tavčar, A.; Gams, M.; Duguleană, M. CulturalERICA: A Conversational Agent Improving the Exploration of European Cultural Heritage. J. Cult. Herit. 2020, 41, 152–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kho, J.; Cho, K.; Cho, Y. A Study on Recent Research Trend in Management of Technology Using Keywords Network Analysis. J. Intell. Inf. Syst. 2013, 19, 101–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bigliardi, B.; Filippelli, S. Investigating Circular Business Model Innovation through Keywords Analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C.; Li, G.; Kamarthi, S.; Jin, X.; Moghaddam, M. Trends in Intelligent Manufacturing Research: A Keyword Co-Occurrence Network Based Review. J Intell Manuf 2022, 33, 425–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a Methodology for Developing Evidence-Informed Management Knowledge by Means of Systematic Review. Br J Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadlalla, A.; Amani, F. A Keyword-Based Organizing Framework for ERP Intellectual Contributions. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2015, 28, 637–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Xiao, H.; Dong, X.; Wang, M.; Xue, L. Tourism Knowledge Domains: A Keyword Analysis. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2012, 17, 355–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Wen, Q.; Qiang, M. Understanding Demand for Project Manager Competences in the Construction Industry: Data Mining Approach. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020, 146, 04020083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de las Heras-Pedrosa, C.; Sánchez-Núñez, P.; Peláez, J.I. Sentiment Analysis and Emotion Understanding during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Spain and Its Impact on Digital Ecosystems. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singrodia, V.; Mitra, A.; Paul, S. A Review on Web Scrapping and Its Applications. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Computer Communication and Informatics (ICCCI), Coimbatore, India, 23–25 January 2019; IEEE: Coimbatore, India, 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H. Rvest Doc. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/rvest/index.html (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- Chang, W. Downloader Doc. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/downloader/index.html (accessed on 11 December 2022).

- Reitz, K. Request-HTML Doc. Available online: https://docs.python-requests.org/projects/requests-html/en/latest/ (accessed on 14 November 2022).

- Dogucu, M.; Çetinkaya-Rundel, M. Web Scraping in the Statistics and Data Science Curriculum: Challenges and Opportunities. J. Stat. Data Sci. Educ. 2021, 29, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, K. Intro to APIs: History of APIs. Available online: https://blog.postman.com/intro-to-apis-history-of-apis (accessed on 25 January 2021).

- Tsou, M.-H.; Kim, I.-H.; Wandersee, S.; Lusher, D.; An, L.; Spitzberg, B.; Gupta, D.; Gawron, J.M.; Smith, J.; Yang, J.-A.; et al. Mapping Ideas from Cyberspace to Realspace: Visualizing the Spatial Context of Keywords from Web Page Search Results. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2014, 7, 316–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brynjolfsson, E.; Hu, Y.; Simester, D. Goodbye Pareto Principle, Hello Long Tail: The Effect of Search Costs on the Concentration of Product Sales. Manag. Sci. 2011, 57, 1373–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Turner, S.J. Website Statistics 2.0: Using Google Analytics to Measure Library Website Effectiveness. Tech. Serv. Q. 2010, 27, 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killoran, J.B. How to Use Search Engine Optimization Techniques to Increase Website Visibility. IEEE Trans. Prof. Commun. 2013, 56, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenoy, A.; Prabhu, A. Keyword Research and Strategy. In Introducing SEO.; Apress: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2016; pp. 73–84. ISBN 978-1-4842-1853-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginsburgh, V.; Moreno-Ternero, J.D.; Weber, S. Ranking Languages in the European Union: Before and after Brexit. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2017, 93, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fidrmuc, J.; Ginsburgh, V. Languages in the European Union: The Quest for Equality and Its Cost. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2007, 51, 1351–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berns, M. English in the European Union. Engl. Today 1995, 11, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crystal, D. English as a Global Language, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003; ISBN 978-0-521-53032-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilherme, M. English as a Global Language and Education for Cosmopolitan Citizenship. Lang. Intercult. Commun. 2007, 7, 72–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L. English as a Global Language in China: Deconstructing the Ideological Discourses of English in Language Education; English Language Education; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 2, ISBN 978-3-319-10391-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairclough, N. Language and Globalization. Semiotica 2009, 2009, 317–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Loewe, I. Globalizacja Kulturowa a Język w Mediach. In Transdyscyplinarność Badań nad Komunikacją Medialną. T. 1, Stan Wiedzy i Postulaty Badawcze; Kita, M., Ślawska, M., Eds.; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego: Katowice, Poland, 2012; pp. 142–153. [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough, N. Critical Discourse Analysis. In The Routledge Handbook of Discourse Analysis; Handford, M., Gee, J., Eds.; Routledge: England, UK, 2012; pp. 9–20. ISBN 978-0-203-80906-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewe, I. The Status, History, People, and Organizations of Polish Media Linguistics. Media Stud. 2022, 88, 1101–1112. [Google Scholar]

- Manovich, L. The Language of New Media. Can. J. Commun. 2002, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunliffe, D. Minority Languages and Social Media. In The Palgrave Handbook of Minority Languages and Communities; Hogan-Brun, G., O’Rourke, B., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2019; pp. 451–480. ISBN 978-1-137-54065-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, K. Translating Facebook into Endangered Languages. In Language Endangerment in the 21st Century: Globalisation, Technology and New Media: Proceedings of the Conference FEL XVI.; Ka’in, T., Laoire, M.O., Ostler, N., Eds.; Auckland: Aotearoa, New Zealand, 2012; pp. 106–110. ISBN 978-0-9560210-4-5. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, D.T.; Fiske, D.W. Convergent and Discriminant Validation by the Multitrait-Multimethod Matrix. Psychol. Bull. 1959, 56, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Denzin, N.K. The Research Act: A Theoretical Introduction to Sociological Methods; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2017; ISBN 1-315-13454-3. [Google Scholar]

- Queirós, A.; Faria, D.; Almeida, F. Strengths And Limitations Of Qualitative And Quantitative Research Methods. Eur. J. Educ. Stud. 2017, 3, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarka, P. Specyfika i Komplementarność Badań Ilościowych i Jakościowych. Wiadomości Stat. 2017, 62, 16–27. [Google Scholar]

- Król, K. Geoinformation in the Invisible Resources of the Internet. GLL 2019, 3, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Wu, H.; Qi, K.; Yu, J.; Yang, S.; Yu, T.; Zheng, J.; Liu, B. A Domain Keyword Analysis Approach Extending Term Frequency-Keyword Active Index with Google Word2Vec Model. Scientometrics 2018, 114, 1031–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberhard, D.M.; Simons, G.F.; Fennig, C.D. Ethnologue: Languages of the World. Available online: http://www.ethnologue.com (accessed on 9 October 2022).

- Krol, K.; Prus, B.; Hernik, J. Cultural Heritage in Development Strategies—Example of Małopolskie Voivodeship, Poland. In Catalogue of the Cultural Heritage of Małopolska. From Past to Modern Regional Development in an International Context; Hernik, J., Krol, K., Prus, B., Eds.; Publishing House of the University of Agriculture in Krakow: Krakow, Poland, 2021; pp. 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, P.C.; Roders, A.R.P.; Colenbrander, B.J.F. Measuring Links between Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Urban Development: An Overview of Global Monitoring Tools. Cities 2017, 60, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage. Adopted by the General Conference at Its Seventeenth Session Paris, 16 November 1972. UNESCO World Heritage Convention. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/conventiontext/ (accessed on 22 August 2022).

- Charter on the Preservation of the Digital Heritage. UNESCO Digital Library. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000179529.page=2 (accessed on 27 September 2022).

- Recommendation Concerning the Preservation of, and Access to, Documentary Heritage Including in Digital Form. UNESCO Digital Library. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000244675.page=5 (accessed on 28 September 2022).

- Conway, P. Digital Transformations and the Archival Nature of Surrogates. Arch. Sci. 2015, 15, 51–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Concept of Digital Heritage. UNESCO. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/themes/information-preservation/digital-heritage/concept-digital-heritage (accessed on 4 January 2023).

- Skiera, B.; Eckert, J.; Hinz, O. An Analysis of the Importance of the Long Tail in Search Engine Marketing. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2010, 9, 488–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budhiraja, A.; Reddy, P.K. An Improved Approach for Long Tail Advertising in Sponsored Search. In Database Systems for Advanced Applications; Candan, S., Chen, L., Pedersen, T.B., Chang, L., Hua, W., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 10178, pp. 169–184. ISBN 978-3-319-55698-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lucia, C.; Pazienza, P.; Balena, P.; Caporale, D. Exploring Local Knowledge and Socio-economic Factors for Touristic Attractiveness and Sustainability. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 22, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casillo, M.; Clarizia, F.; D’Aniello, G.; De Santo, M.; Lombardi, M.; Santaniello, D. CHAT-Bot: A Cultural Heritage Aware Teller-Bot for Supporting Touristic Experiences. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2020, 131, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, S.M.C.; Guerreiro, J.; Ali, F. 20 Years of Research on Virtual Reality and Augmented Reality in Tourism Context: A Text-Mining Approach. Tour. Manag. 2020, 77, 104028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Rita, P.; Moro, S.; Oliveira, C. Insights from Sentiment Analysis to Leverage Local Tourism Business in Restaurants. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2022, 16, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, S.-P.; Yoo, H.S.; Choi, S. Ten Years of Research Change Using Google Trends: From the Perspective of Big Data Utilizations and Applications. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2018, 130, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitting, K.-M.; Lammers-van der Holst, H.M.; Yuan, R.K.; Wang, W.; Quan, S.F.; Duffy, J.F. Google Trends Reveals Increases in Internet Searches for Insomnia during the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Global Pandemic. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2021, 17, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyoubzadeh, S.M.; Ayyoubzadeh, S.M.; Zahedi, H.; Ahmadi, M.; Niakan Kalhori, S.R. Predicting COVID-19 Incidence Through Analysis of Google Trends Data in Iran: Data Mining and Deep Learning Pilot Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill 2020, 6, e18828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavelea, A.; Nisioi, S. Ștefana Is It Over Yet? A Socio-Psychological Analysis of the Romanians’ Behaviour during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Styles Commun. 2022, 14, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens-Davidowitz, S. The Cost of Racial Animus on a Black Candidate: Evidence Using Google Search Data. J. Public Econ. 2014, 118, 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.Y.; Rojas, R.R.; Convery, P.D. Forecasting Stock Market Movements Using Google Trend Searches. Empir. Econ. 2020, 59, 2821–2839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, M.-H.; Chen, M.-Y.; Liao, E.-C. A Deep Learning Approach for Financial Market Prediction: Utilization of Google Trends and Keywords. Granul. Comput. 2021, 6, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, T.L.D. Which Google Keywords Influence Entrepreneurs? Empirical Evidence from Vietnam. APJIE 2019, 13, 214–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangwayo-Skeete, P.F.; Skeete, R.W. Can Google Data Improve the Forecasting Performance of Tourist Arrivals? Mixed-Data Sampling Approach. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 454–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhme, M.H.; Gröger, A.; Stöhr, T. Searching for a Better Life: Predicting International Migration with Online Search Keywords. J. Dev. Econ. 2020, 142, 102347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowlands, I.; Nicholas, D.; Williams, P.; Huntington, P.; Fieldhouse, M.; Gunter, B.; Withey, R.; Jamali, H.R.; Dobrowolski, T.; Tenopir, C. The Google Generation: The Information Behaviour of the Researcher of the Future. Aslib Proc. 2008, 60, 290–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kumar, M.; Bindal, A.; Gautam, R.; Bhatia, R. Keyword Query Based Focused Web Crawler. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2018, 125, 584–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, M.K. White Paper: The Deep Web: Surfacing Hidden Value. J. Electron. Publ. 2001, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höpken, W.; Eberle, T.; Fuchs, M.; Lexhagen, M. Google Trends Data for Analysing Tourists’ Online Search Behaviour and Improving Demand Forecasting: The Case of Åre, Sweden. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2019, 21, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Wöber, K.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Representation of the Online Tourism Domain in Search Engines. J. Travel Res. 2008, 47, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z.; Pan, B. Travel Queries on Cities in the United States: Implications for Search Engine Marketing for Tourist Destinations. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Pan, B.; Law, R.; Huang, X. Forecasting Tourism Demand with Composite Search Index. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dergiades, T.; Mavragani, E.; Pan, B. Google Trends and Tourists’ Arrivals: Emerging Biases and Proposed Corrections. Tour. Manag. 2018, 66, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siliverstovs, B.; Wochner, D.S. Google Trends and Reality: Do the Proportions Match? J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2018, 145, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Pan, B.; Evans, J.A.; Lv, B. Forecasting Chinese Tourist Volume with Search Engine Data. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 386–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Keyword in PL/ENG | Definition | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dziedzictwo kulturowe/cultural heritage * | Heritage is the cultural legacy which we receive from the past, which we live in the present, and which we will pass on to future generations. | [89] |

| 2 | Cyfrowe dziedzictwo kulturowe/digital cultural heritage ** | The digital heritage consists of unique resources of human knowledge and expression. It embraces cultural, educational, scientific, and administrative resources, as well as technical, legal, medical, and other kinds of information created digitally, or converted into digital form from existing analogue resources. | [90,91] |

| 3 | Cyfrowe artefakty/digital artefacts *** | Digital artefacts may be accessible from their beginnings in an electronic format (born digital) or may be a result of digitisation, i.e., a digital representation, replica, or digital substitute. Digital substitutes can take on the form of (faithful) virtual representations (3D), or may be digital phantoms or only an ersatz of the original (a so-called digital proxy), e.g., small illustrative graphics. | [10,92] |

| Item | Keyword Tool 1 | Keyphrases | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural Heritage | Digital Cultural Heritage | Digital Artefacts | |||||

| PL | EN | PL | EN | PL | EN | ||

| 1. | Keyword suggestions | 210 | 309 | 45 | 54 | 56 | 82 |

| 2. | Questions | 29 | 84 | 25 | 3 | 11 | 11 |

| 3. | Prepositions | 63 | 121 | 22 | 15 | 43 | 24 |

| Total | 302 | 514 | 92 | 72 | 110 | 117 | |

| Keyphrase | Online Application | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kparser 1 | SISTRIX Keyword Tool 2 | |||

| PL | EN | PL | EN | |

| cultural heritage | 165 | 409 | 200 | 188 |

| digital cultural heritage | 18 | 91 | 100 | 133 |

| digital artefacts | 14 | 84 | 56 | 109 |

| Total | 197 | 584 | 356 | 430 |

| Keyphrases 1 | PL | EN | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Keyphrases | Percentage (%) | Number of Keyphrases | Percentage (%) | |

| cultural heritage | 192 | 33.3 | 204 | 60.2 |

| digital cultural heritage | 196 | 34.0 | 49 | 14.5 |

| digital artefacts | 189 | 32.8 | 86 | 25.4 |

| Total | 577 | 100 | 339 | 100 |

| Keyphrases | Cultural Heritage | Digital Cultural Heritage | Digital Artefacts | Total | Percentage (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | Query Language | PL | EN | PL | EN | PL | EN | ||

| 1. | Keyword Tool | 302 | 514 | 92 | 72 | 110 | 117 | 1207 | 32.7 |

| 2. | Kparser | 165 | 409 | 18 | 91 | 14 | 84 | 781 | 21.2 |

| 3. | SISTRIX Keyword Tool | 200 | 188 | 100 | 133 | 56 | 109 | 786 | 21.3 |

| 4. | Keyword Sheeter | 192 | 204 | 196 | 49 | 189 | 86 | 916 | 24.8 |

| Total | 859 | 1315 | 406 | 345 | 369 | 396 | 3690 | 100 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Król, K.; Zdonek, D. Cultural Heritage Topics in Online Queries: A Comparison between English- and Polish-Speaking Internet Users. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5119. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065119

Król K, Zdonek D. Cultural Heritage Topics in Online Queries: A Comparison between English- and Polish-Speaking Internet Users. Sustainability. 2023; 15(6):5119. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065119

Chicago/Turabian StyleKról, Karol, and Dariusz Zdonek. 2023. "Cultural Heritage Topics in Online Queries: A Comparison between English- and Polish-Speaking Internet Users" Sustainability 15, no. 6: 5119. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065119