1. Introduction

The technological progress of the digital age, which tends to cancel the physical distance between people, objects and places, is profoundly transforming the modes of transport of people and goods and service distribution systems. All over the world, large segments of infrastructure networks are being replaced or transformed to meet new requirements to cut connection times and to tend towards resource optimization.

In accordance with these changes, various circumstances lead to the abandonment of many railway sections. One of the main reasons is that they connect scarcely populated areas or areas with no significant economic interests because they have been created for the distribution of goods that are now considered obsolete or distributed in a faster and safer way.

The growing interest for environment protection and the global economic crisis impose the reuse of abandoned railway heritage to follow circular economy principles [

1].

According to the cradle-to-cradle principle, which takes the biological processes of metabolic production from nature as a model to create a technical metabolic flow of industrial materials, a substantial and widespread heritage such as the railway system cannot remain unused. The entire abandoned railway system can have a second life, as within natural metabolisms, where each component can be derived from continuous recycling and reuse processes [

2,

3,

4,

5]. Indeed, this principle can also be applied to building components and up to entire buildings that undergo reuse or requalification interventions to increase and integrate their performance, with the aim of adequately satisfying requirements.

The disused railway heritage consists of railway lines and numerous buildings (stations, tollgates, warehouses, etc.) scattered along the network. Its complexity and variety, as well as its very nature as a system of buildings physically connected by the network and widespread throughout the territory, make these assets strategic resources to generate transformations in large areas, according to development and enhancement spatial scale objectives. The dismantling conditions are essential to guide reuse choices.

In Italy, there are unattended stations and abandoned stations. These two different conditions offer different opportunities for reuse and, at the same time, require different solutions. The unattended stations are those that no longer require the presence of railway personnel due to the evolution of technologies. The abandoned stations, on the other hand, are no longer used because since the 1940s–50s, urban drift and the development of the automotive industry has led to the disposal of thousands of kilometres of railway lines, in addition to sections of active lines abandoned following the realization of route variants for high-speed trains. Today, there are numerous proposals and projects for the reuse of these sections for tourist purposes because of the naturalistic and cultural resources of the areas they cross [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. However, their reuse as a business case has never been considered.

So far, the issue of rail heritage reuse has been approached mainly on a case-by-case basis, disregarding a systemic view. Only in recent years, given the scale of the problem, have ad hoc research and legislative acts been developed.

Our research aim is to define criteria for the evaluation of alternative reuse strategies, appropriate to the Italian framework, which consider the track layout as one of the networks shaping the region and supporting and strengthening the network of goods and services constituting the territorial specificity. We should stop considering the abandoned railway network only as a means of transporting goods and travellers, for which the point of departure and arrival is important, as is the time needed to connect the nodes. The research presented in this article focuses on defining a method for guiding decisions on the reuse of disused railway assets, following an enhancement and upcycling approach, and considering both the characteristics of the resources to be reused and the local context. The research question addressed is how to evaluate reuse projects of railway buildings and networks considered as a whole system, while predicting the impacts that new activities will have on the context, in terms of the alteration of social and economic dynamics and the physical transformation of the settlement system. Furthermore, the required decision-aiding methodology should enable to assess the ability of reuse projects to protect the identity of existing buildings, in spite of the adaptations required by new uses, in order to preserve the identity of infrastructures revealing the technological and socio-economic evolution of territories.

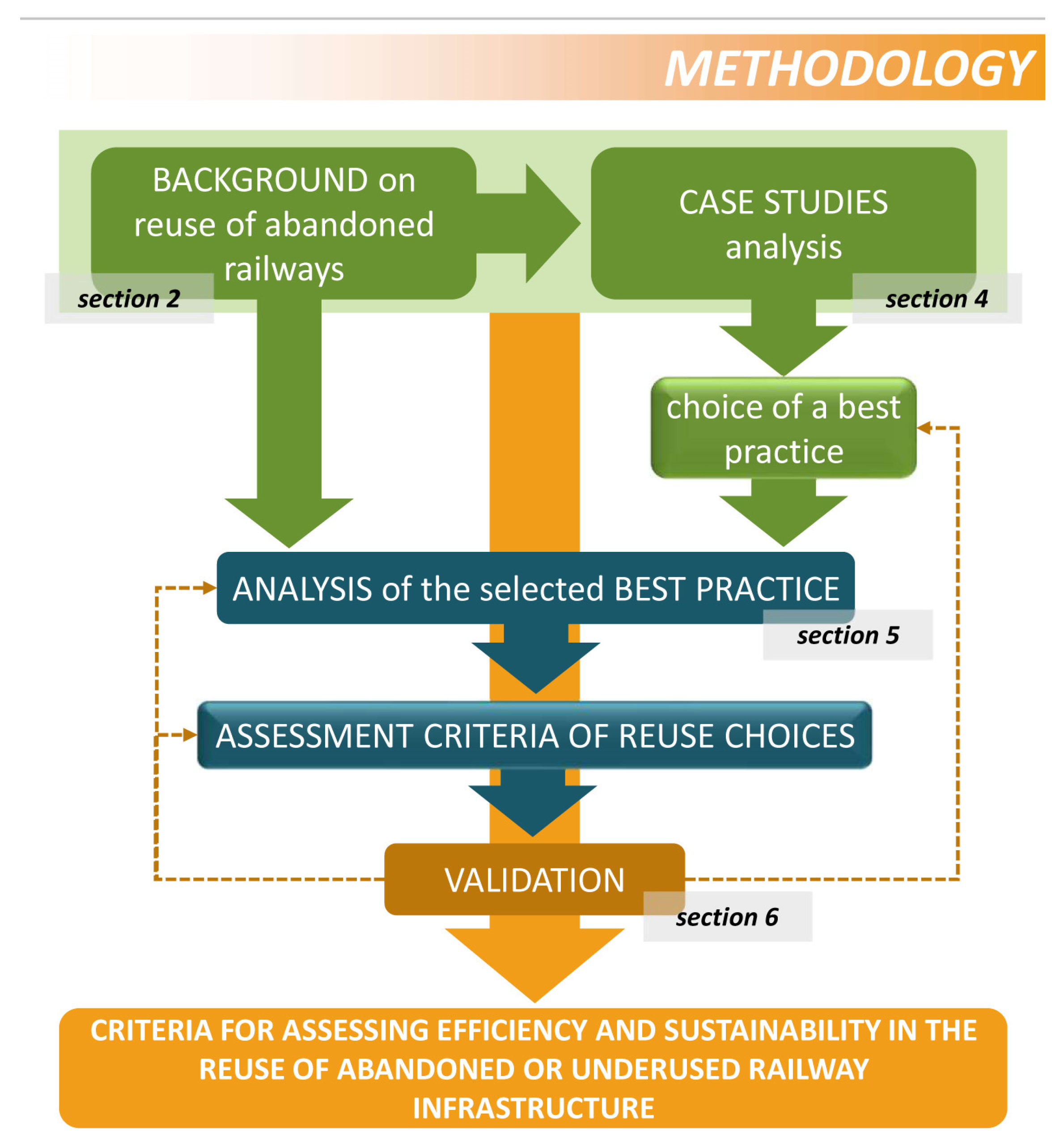

Figure 1 explains the research methodology as it relates to the articulation of the present paper.

2. Background

The first step of the research was the analysis of the state of the art of the reuse of railway heritage, examining the scientific literature on two specific themes:

the positive effects of building reuse and the impacts determined by the settlement of new functions on an urban and territorial scale;

the adopted approaches for the protection and reuse of railway heritage through the examination of practical experiences and scientific studies.

This first phase of investigation pointed out critical issues that led to widening the field of inquiry to the Italian context and to deepening the analysis of the process of railway decommissioning in Italy and the main legal references in force.

2.1. Scientific Literature

2.1.1. Impacts of Building Reuse

The cultural debate on building reuse began in the 1800s, when the urban development brought about by the industrial revolution led restorers to question the value of the building in relation to its “utility”. E.E. Viollet-le-Duc, regarding the reuse of historic buildings, stated “[…] the best means of preserving a building is to find a use for it, and to satisfy its requirements so completely that there shall be no occasion to make any changes” [

11] (p. 4).

The choice to reuse existing buildings derives from the fact that to each building we can assign multiple values (economic, social, cultural, functional, environmental, etc.). The aim of reuse is conservation and, when possible, to increase these values through a new harmonization between conservation actions and necessary transformations. Reuse is justified by numerous benefits: in many cases, the location value and the quality (construction, aesthetics, durability, etc.) of existing buildings make them preferable to new buildings [

12].

Extensive scientific literature on the subject of reuse highlights the potential positive effects on urban and territorial scale, in terms of increasing the market value of soils and buildings, and of social promotion and economic development that can be observed in the surrounding areas [

13]. The establishment of new functions can, in fact, encourage new public and private investments, favouring the establishment of related activities and the creation of support services in the area in which the reuse intervention is carried out [

14,

15].

The care for the conservation and enhancement of cultural resources indicates the degree of interest and appreciation communities have of their own culture. The influence industrial activities or infrastructures have had on the urban pattern is difficult to erase, even after its abandonment [

16].

Reuse contributes to the life cycle increase of buildings that are abandoned or being dismantled since use determines the need to guarantee conditions of efficiency through maintenance actions [

17]. Preventing and slowing down the processes of degradation and favouring continuity through adaptations of the built heritage to new needs of use are closely related strategies to the “sustainable development” objectives. The existing artifacts become resources that have to be preserved and reused to promote the protection of cultural identity. A correct approach to the reuse project allows the increase of knowledge and understanding of the cultural meaning of architectural solutions, of the constructive reasons, of the choice of materials and of the relationships between the elements, guaranteeing continuity with the material culture of the past [

18].

2.1.2. Approaches for the Protection and Reuse of Railway Heritage

Awareness of the importance of railway heritage as evidence of technological evolution is widely accepted in the international community [

19,

20,

21]. As an example, in the 1950s, the “Protection of Railway Heritage” movement emerged in the United Kingdom. In March 1994, the British government published a political orientation document for local authorities, which expressed the objective of reducing the need to travel. This political position has given new strategic directions for the achievement of more sustainable development models in transport planning and policy [

22]. In France, after the 1960s, historic railway stations and trains began to be used for tourism purposes. The historic stations were managed by non-profit organizations such as the French Association of Friends of Local Railways (FAFLR). Nevertheless, commercial interests, which have been strong since the early history of rail transport, have remained significant and have sometimes grown with tourist reconversion [

23]. In Germany, the first railway heritage preservation societies arose in the mid-1960s. The achieved results led to the reuse of around 100 historic buildings for tourism purposes [

24].

Similar choices were made in the United States since the 1970s. First, the “National Register of Historic Places” was established. This register indicated historic railway stations worthy of preservation. After that, legislative measures were issued to allow and promote the reuse of stations [

25]. Finally, the US government has implemented several projects in various states, involving voluntary civil society organizations.

Architectural elements and cultural landscapes related to disused railway infrastructure have been investigated from two perspectives, both concerning heritage. Some authors put the stress on the inherent heritage value [

26,

27] while others highlight the potential for local tourism development [

28,

29,

30].

In particular, railway buildings that are part of historic industrial buildings are frequently considered for reuse purposes. The change in the railway construction process due to technological evolution, railway development and the influence of the local culture allows for multiple values to be assigned to abandoned or under-utilized railway heritage [

31]. In this heritage preservation scenario, the most significant structures are the stations.

In Europe and in the United States, the protection of railway heritage is usually based on a voluntary approach and on the action of non-profit organizations. New use destinations include museums and tourism-related activities. In the remaining cases, the main support comes mainly from local governments, with the aim of contributing to regional development even if waiting lists for investments and projects funded by the public administration slow down the process.

In the scientific field, numerous researchers have addressed the issue of the reuse of railway heritage, highlighting the correlation between railway track reconversion in greenways with socio-demographic and landscape features. It is also demonstrated that the layout density, orography and presence of cultural interest elements are incentives for green roads [

32]. However, abandoned railways may have a different use apart from greenways, depending on the distances they connect, their structure (linear or network, such as multi-centre or polynuclear network cities) and the presence of an urban or rural community in the area in which they are located [

33]. In some cases, the carried-out research has developed decision-support methodologies to evaluate alternative hypotheses of reuse that improve the accessibility to environmental and cultural resources networks through disused railway connections [

34,

35].

The opportunity of opening the evaluation process of new use destinations to local communities and stakeholders interested in the future development of the area is essential to move from an urban planning exercise to a shared strategic plan. While in traditional approaches the choices are not always based on an extensive survey of the preferences expressed by the stakeholders, complex urban interventions must be representative of different values, related not only to the economic and financial dimension, but also to the environmental and social dimension [

36].

Among the priority objectives to ensure effective urban regeneration through the reuse of disused railway areas, Gehan Ahmed Nagy Radwan and Manal M. F. El-Shahat highlight the need to grant open spaces to public and urban structures to attract people from different backgrounds [

37].

Underground spaces are rather recent structures with a high potential for the future. The efficiency of underground transport and the importance of multiple uses of space in densely built urban areas are some of the advantages that these spaces can offer. However, many of the underground projects carried out are still not adequate for users. These spaces have their limits. Some qualities that are evident for buildings above ground, such as daylight or a view, are rather difficult to obtain in underground spaces. In these spaces, therefore, the word quality becomes rather critical. The literature that architects can refer to on these topics is rather fragmentary and difficult to find [

38].

Reuse strategies, as well as the expected impacts in terms of context enhancement, should be identified according to the territory peculiarities and the characteristics of the railway system to be reused.

2.2. Railway Dismantling in Italy

During the twentieth century, the history of the Italian railway system was profoundly linked to historical events and socio-economic transformations: the war destruction, the reconstruction, the demographic crisis of inland areas and the industrial development of cities. Railway dismantling is due to multiple reasons, such as the transition from an agricultural economy to industrial production concentrated in the metropolis and the expansion of the automotive industry, often favored by public incentives and the extension of the road network.

Between 1955 and 1972, over 600 km of state-run railway lines and about 1400 km of concession routes [

39] were dismantled, especially in the internal areas of the country. Over the past twenty years, investments have been concentrated mainly on high-speed lines that connect big cities, committing less profitable connections to road transport.

In 2008, a two-million-euro funding program was dedicated to enhancing disused railway lines and converting them to greenways. This started the reuse process. Subsequently, in 2013, the Ferrovie dello Stato (FS, Italian State-owned railways) group developed a new redevelopment project for the socio-environmental reuse of unused real estate, signing a memorandum of understanding—“Community stations”—that provides for the re-functionalization of social inclusion activities for weak subjects, civil protection activities, cultural initiatives and historical and environmental enhancement [

40,

41]. This protocol was followed by further grants and, to favor the creation of motorbike and tourist cycle itineraries, the Law n. 106, 29 July 2014, granted companies, cooperatives and associations mainly constituted by young people free-of-charge use of disused railway stations for periods of time not exceeding 7 years.

The provisions of Law 106/2014 represent an affirmation of what has already been implemented by the company FS, engaged since 2001 in actions of the social reuse of disused railway stations and lines.

In 2017, with the Law n. 128, 9 August 2017, pertaining to “Provisions for the establishment of tourist railways in areas of particular naturalistic or archaeological value, through the reuse of disused lines or those in a dismantling phase”, the aim was to safeguard and enhance the railway lines of particular cultural, landscape and tourist value. The law addresses railway tracks, stations, appurtenances and historical and tourist rolling stocks.

For the FS group and the community, this reconversion has mutual advantages: if, on one hand, the group no longer has maintenance costs for the building and the surrounding green areas, on the other hand, the bailee has a free-of-charge premise for his activities.

Moreover, for the presence of companies, cooperatives or associations, the buildings and sites are protected from vandalism and the perception of safety for both customers and citizens is greater. Not all gratuitous bailment contracts, however, have yielded good results because the activities have not been supported by economic investments that could guarantee the fulfillment and continuity of the presented projects over time.

To classify the experiences launched so far all over the nation, the FS group has signed a Memoranda of Understanding with local institutions and the most important Italian organizations. The gratuitous bailment contracts, provide that spaces owned by Rete Ferroviaria Italiana (RFI, one of the companies of the FS group), that are no longer functional for railway operations can be claimed exclusively by local authorities (provinces, municipalities, etc.) and by associations operating in the social sector and, more generally, by non-profit organizations.

RFI sites that are no longer functional for railway operations are, in fact, available on gratuitous bailment only for the implementation of non-profit social services projects. As a rule, the duration of the contract is 4 years and the commitment of the bailee is to realize requalification and/or maintenance interventions.

As deducible from the 2017 Sustainability Report of the FS group, the reuse of real estate assets and dismissed railway lines is part of the corporate social responsibility (CSR) actions related to the community and social policies, responsibility issues and social enhancement of Italian railway assets. This action can be ascribed to goal n. 9 of the UN Agenda 2030, Industries, Innovation and Infrastructures, satisfying two of the proposed targets:

to develop quality, reliable, sustainable and resilient infrastructure, including regional and trans-border infrastructure, to support economic development and human well-being, with a focus on affordable and equitable access for all;

to promote inclusive and sustainable industrialization and, by 2030, significantly raise industry’s share of employment and gross domestic product, in line with national circumstances, and double its share in least developed countries.

In fact, the FS displays this goal in its materiality matrix as sustainable management of its infrastructures in relation with goal n. 5, gender equality considered as diversity and inclusion. They connected this policy to fundraising activities and to an agreement protocol with Banca Etica in which the collaboration between the FS and Banca Etica will promote and support integrated projects.

In particular, the FS will involve Banca Etica in the selection of the beneficiaries of the areas subject to redevelopment and will communicate the guidelines to use the services of Banca Etica to the selected subjects. Banca Etica, on the other hand, will promote, through dedicated calls on its crowdfunding network, the fundraising for redevelopment projects, and will promote cultural events to present projects and offer integrated banking and credit services.

In December 2018 there were 1473 gratuitous bailment contracts in force and approximately 3,623,402 square metres were available for the community. Of these, approximately 106,645 square metres are station buildings and approximately 351,657 square metres are referred to land [

42].

The quantitative dimension of the “unattended stations” phenomena will grow further in the next few years due primarily to technological innovation. This will lead to far-reaching financial implications (heritage management), sales and marketing implications (assistance to customers) and social implications (public order) to which we have to find suitable solutions in advance.

A cost reduction policy—that is anyhow a focus point for the FS budgetary policy—must also consider unattended stations. This has to be done to maximize the economic advantages that technological innovation has already brought to plant management, favoring a new reorganization of work with a significant reduction in personnel costs. It is therefore necessary to hypothesize a redefinition of the use of these buildings, for extra railway activities that do not deny the station’s intended use as a community service.

The Italian government’s strategy places emphasis on the crucial role that businesses have for communities and for the responsible management of economic activities as value building for businesses, citizens and communities. This certainty is supported by two typical features of Italian companies: the ability to settle in and to establish a deep relationship with the areas in which they operate, and the social dimension in terms of industrial relations and social commitment. A heritage of our companies that risks deterioration under the pressure of international dynamics and that the government intends to enhance and support through strategic actions is shared with all stakeholders.

In addition to having positive effects on workers and on the regions they operate in, a correct strategic approach to CSR entails an advantage for the competitiveness of companies, in terms of risk management, cost reduction, access to capital, customer relations, human resources management and innovation capacity [

43].

In recent years, large companies in the transport industry have intensified their efforts to integrate the principles of sustainability in all business activities to succeed in the contemporary world and for the awareness that their choices can affect people’s quality of life and natural balance [

44].

3. Methodology

The analysis of the scientific literature confirms the need to verify the feasibility of changing the use of railway heritage with the aim of generating local development. This process may lead to the use of the infrastructure to host and/or to connect systems of cultural heritage, accommodation facilities and valuable economic activities in order to develop a renewed geographical and spatial model of living. The interpretation of land’s physical and cultural features leads to the setting of the constraint levels, but also, and above all, to a structural hypothesis of an integrated fruition system of the various resources. The basic elements of the effectiveness of this model, which associates use and preservation purposes, can lead to the expansion of enhancement strategies, through a hypothesis of use of urban and extra-urban nodes—stations not only to provide services to stakeholders but also to influence the development trajectory in a positive way, to promote the knowledge of the sites.

The research refers to methodologies for evaluating the impacts of adaptive reuse projects that have been previously affirmed in the scientific literature. In particular, with respect to the need to protect the identity of the built heritage, evaluation criteria and indicators have been developed from previous research projects [

45,

46,

47]. Similarly, for the impacts on the socio-economic system, research conducted by several authors in the last decade [

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53] were taken as references.

Our research is focused on creating and comparing alternative strategies for the efficient and effective reuse of abandoned railways through a systemic and multicriteria approach (

Figure 2).

The aim of this research is to define a sustainable management model for abandoned railway infrastructures and to define efficiency improvement criteria for reuse. The evaluation of what has already been done on the basis of policies and regulations and the analysis of different Italian and European case studies brought us to the choice of a best practice.

The selected best practice has been thoroughly analysed thanks to data collection (data were collected through tables and questionnaires) in collaboration with the museum’s senior management and an interview with a key informant. The objective of the interview was to analyse the role of trusts in the model performance:

to identify the key benefits;

to analyse if the funding model is effective for the reuse of abandoned buildings;

to understand if the model is replicable.

The last phase of the research lead to a generalization stage compared to what was deduced from the study cases. The aim was to extrapolate general rules of conduct applicable to new/different cases to obtain eco-efficient results compliant to acceptability criteria derived from the three analysed dimensions. This inductive reasoning requires the implementation of the conclusions in punctual interventions.

This research analysed three different dimensions, physical/cultural, social and economic, related to three connected requirement classes that identify the focus to which general and specific criteria refer. The environmental dimension will not be investigated here as benefits of the examined study case and sustainability issues are taken for granted. The project itself is sustainable, implying reuse, no soil consumption and benefits for the entire neighbourhood. General criteria represent the goals and each criterion has different key factors or sub-goals. Specific criteria have been identified for each key factor describing how to calculate the indicator or specific factor. Specific factor values are calculated on a percentage basis and reflect their weight.

Then, starting from the matrix outcome measures, as a result of the preceding analysis, the data crossing and the evaluation of each transformation for each dimension, each criterion will be attributed a weight that will also reflect the importance of each dimension.

The final step involves control of the results of the assessment/validation, testing of the model reproducibility and review of the methodology, applying it to a specific case.

The observations and the results of the application lead to the definitive formulation of the analytical criteria generally applicable.

The research is structured on the possibility of identifying four sets of indicators. The first indicator describes life quality of the railway system (including buildings, tracks, platforms, etc.), providing a framework for the social and economic impacts determined from reuse. The second set of indicators aims to describe the capacity of the reuse project to restore a balance between conservation and transformation of the built heritage. The third set of indicators describes the level of cultural consensus for the examined project and the fourth, the economic and financial sustainability.

It appears essential at this point to make a distinction between the sustainability assessment of the project as a whole and the assessment on economic sustainability tout court, taking into account that, in this phase of the project (at a very early stage since it was the first year of operation), the economic and financial sustainability considers only positive and negative cash flows (financial and manufacturing capital) to estimate the investment and to maximize strategies for creating value.

Instead, the overall sustainability valuation methodology has to be examined, taking into account the concept of business sustainability, as a state where the demands placed upon the environment, the cultural heritage preservation and the social issues can be met without reducing their capacity to provide assets for future generations.

The complexity of measuring a project’s economic sustainability is given by the fact that it has to consider a very large number of key factors, among which are not only measurable factors, such as scalability, extensibility, manageability, financial capital, manufacturing capital, economic and technical feasibility, etc., but also a large number of intangibles such as natural capital, human capital, cultural heritage, social desirability and cultural consensus.

A big help can come from a sustainability report that contains all necessary data and key performance indicators. Among possible research developments, one is to measure the factors that make a project successful and to make sure that the financial information that could influence investors’ decisions is included in the financial statements. This can be achieved, setting the basis for an integrated reporting (Directive (EU) 2022/2464 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 December 2022 amending Regulation (EU) No 537/2014, Directive 2004/109/EC, Directive 2006/43/EC and Directive 2013/34/EU, as regards corporate sustainability reporting (Text with EEA relevance)) for the Postal Museum, evaluating materiality and key performance indicators.

Furthermore, measuring sustainability can help us to understand if the project is fostering regional competitiveness, as this cannot be declined as economic growth alone. According to Esser et al. [

54], the competitiveness of a region can be considered as a meta-level and expressed as the ability of an area to generate high and rising incomes and improve the livelihoods of residents. This interpretation in terms of wealth, also stated by Aiginger [

55], led to an emphasis on “soft” or intangible assets as sources of competitiveness, including, together with the productive capacity, human and cultural capital, innovative capacity and sustainability [

56].

4. Study Cases: Reused Railway Stations

This research led to the analysis of numerous cases of railway building reuse, to verify the feasibility of adapting to new functions not only from the technical point of view, i.e., the quality and effectiveness of the project solutions, but also in terms of effects on the socio-economic context.

Many railway stations around the world have been creatively and profitably reused. Five main categories of new uses have been identified: artistic and cultural production and/or fruition; retail; integration and social cohesion; tourist services, accommodation and restaurants; sports facilities and public parks. Out of the cases examined, four examples were selected for each category of new use, to define possible variations of use within a single use category. Selected examples are listed in the following figures, which show the approaches that have been adopted worldwide to reuse and to manage this critical cultural heritage.

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 summarize the practices selected for the first phase of case study investigation as follows: artistic and cultural production and/or fruition (Gare d’Orsay, Pietrarsa, Hamburger Bhanhof, Postal Museum), retail (Shopping Estaçao Curitiba, El Galpòn Market, Atocha Railway Station, Gare Maritime), integration and social cohesion (Flèche d’Or, Boscoreale, Arci La Locomotiva, Casa Mediterraneo Headquarters), tourist services, accommodation and restaurants (Bullona, Deptford Station, St. Louis Union Station Hotel, Avellino-Rocchetta) and sports facilities and public parks (Virgin Active Fitness, Promenade Planteé, NY High Line, Vias Verdes Greenways).

For each case study, the main transformations needed for the settlement of the new function were examined. In addition, advantages and critical points were identified in relation to the implementation of the reuse project, the management of the new function and the impacts on the urban and territorial context. The results of the analysis are summarized in

Table 1.

The analysis of interventions for the reuse of railway heritage has shown a wide diffusion of interventions that are limited to the reuse of railway buildings (stations, warehouses, etc.). There are fewer reuses of the infrastructure network in public parks, tourist routes and greenways. Nevertheless, there are still a few experiences of reusing the entire station/building/railway system in a comprehensive project to maximize sustainability.

Among the examined cases, the Postal Museum (the Mail Ride) in London has been identified as an example of best practice, as it shelters a new cultural use capable of producing significant impacts on the socio-economic system in a metropolitan area, while dealing with an all-underground railway network. The reuse project of the Postal Museum is a virtuous example in terms of sustainability for the following reasons: the reuse concerns both the railway station and the infrastructural network; the new use satisfies social/cultural needs; the project resulted in minimal transformations, limiting the intervention costs; and the reuse increased the attractiveness of the site, fostering the development of a degraded urban area.

5. The Postal Museum and Mail Ride, a Case Study Analysis

This research analyses the Postal Museum project after one year of operation. This best practice has been investigated by considering three different dimensions—social, economic and physical/cultural—and for each a set of parameters. Data collection (data were provided by The Postal Museum) started from general data on the museum, data for the social, economic and physical/cultural dimensions and neighbourhood data. At the same time, a key informant interview was carried out to provide a better understanding of the role of trusts in the model performance. At a time when people use the traditional postal service increasingly less, as a result of the use of new technologies, the opening of a postal museum is a very ambitious project.

The Postal Museum opened in July 2017 after transforming a disused Clerkenwell printing factory into an interactive visitor attraction. The museum brings together the archive of the Royal Mail Group PLC and Post Office Ltd. and brings back to life the Mail Rail—situated across the street—which is a stretch of underground railway opened in 1927 to transport parcel traffic and avoid overhead congestion.

The Postal Museum is in Phoenix Place within the constituency of Holborn and St. Pancras, local authority Camden, in the Region of London (

Figure 8).

In April 1965, the London Borough of Camden replaced the former metropolitan boroughs of Hampstead, Holborn, and St. Pancras. It was named after the first Earl Camden, Charles Pratt, who started the development of Camden Town in 1791.

The borough of Camden is in the northwestern part of London, comprising almost 22 square km, and is a borough of diversity and contrasts. Business centres such as Holborn, Euston and Tottenham Court Road contrast with exclusive residential districts in Hampstead and Highgate, thriving Belsize Park, the open spaces of Hampstead Heath, Parliament Hill and Kenwood, the youthful energy of Camden Town and subdivided houses in Kentish Town and West Hampstead, as well as areas of relative deprivation. The council has designated 40 conservation areas that cover approximately half the borough, while more than 5600 buildings and structures are listed as having special architectural or historic interest. Camden is well served by public transport, including three main-line railway stations (St. Pancras, King’s Cross and Euston) and St. Pancras International, with extensive bus, tube and suburban rail networks. Camden is home to 11 higher education institutions and to the largest student population in London, with more than 26,500 higher education students living in Camden, 54% of whom are from overseas. Camden’s population is ethnically diverse. In 2011, 34% of Camden residents were from black or minority ethnic groups (increased from 27% in 2001). A further 22% are non-British white residents including Irish and others originating mainly from English-speaking countries in the new world, the EU, Eastern Europe and beyond. In 2016–17, the top five nationalities of Camden residents requesting national insurance numbers to work in the UK were Italian (13%), French (12%), Spanish (7%), American (5%) and Australian (5%) [

57].

On one side, in the neighborhood, the council is involved in major development works such as King’s Cross Central area development, the Community Investment Program (CIP) and the Phoenix Place/Mount Pleasant housing development project. The Community Investment Program (CIP) is an ambitious 15-year plan to invest over GBP 1 billion in schools, homes and community facilities in Camden. The CIP provided 1365 square metres of community facilities, including the new St. Pancras Community Centre, and secured 193 apprenticeship opportunities and 141 work experience opportunities [

58]. On the other hand, Blue Sky Building on behalf of the Royal Mail Group is working on the development of two parcels at Phoenix Place and Calthorpe Street. The planning permission grants consent for 681 new homes, 163 of which will be available as affordable rented or intermediate homes, as well as commercial spaces and public realms. According to the Mount Pleasant working plan, the development will generate a range of community and economic benefits, through both the Section 106 agreement (S106 or planning obligations in the UK, are legal agreements between Local Authorities and developers linked to planning permissions) and through wider investment and job creation [

59]. As part of this overall urban district development plan, the repurposing of the old railway line for mail delivery into a Postal Museum is considered as a strategic investment.

The Postal Museum is divided into two areas: the museum itself and the Mail Rail. The museum is housed in a 1920 repurposed building adjacent to the underground railway. The museum’s collection features artefacts and objects relating to the history of the Royal Mail and its predecessors. The museum building also houses the Royal Mail Archive that contains records of the Post Office from 1636 to the present day, a discovery room with its library, a shop and a cafeteria. Although the Postal Museum is an independent charity, it is closely linked with the Royal Mail Group, not only through its object of interest, but also as it manages the Royal Mail Archive. A section of the Post Office Underground Railway is also part of the museum.

The Post Office Railway (

Figure 9 and

Figure 10), known as Mail Rail since 1987, is a 2 ft (610 mm) narrow gauge, driverless underground railway in London that was built by the Post Office with assistance from the Underground Electric Railways Company of London, to move mail between sorting offices. It operated from 1927 until 2003. The line ran from Paddington Head District Sorting Office in the west to the Eastern Head District Sorting Office at Whitechapel in the east, a distance of 6.5 m (10.5 km). It had eight stations, the largest of which was underneath Mount Pleasant, London’s largest sorting and delivery office and the main base for the railway.

Construction of the tunnels started in February 1915. In February 1927, the first section, between Paddington and the West Central District Office, was available for training. The line became available for the Christmas parcel post in 1927 and letters were carried from February 1928.

Mail Rail today is a ride into the former engineering depot of Mail Rail on board a miniature train into the original tunnels below Royal Mail’s Mount Pleasant sorting office. During the ride, visitors can see the original station platforms and see and hear the history and the people who worked on it. Thanks to the British Postal Museum and Archive (BPMA), a British independent charitable trust, and to the Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF), the Postal Museum opened on 28 July 2017 with Mail Rail opening on 4 September 2017.

The conversion and reuse of industrial heritage emphasizes cultural regeneration, preserving landscape, landmarks and collective identities in a sustainable way (

Figure 11,

Figure 12,

Figure 13,

Figure 14 and

Figure 15). Mail Rail represents a piece of industrial heritage, and as such, it had to be preserved, but the new feature is to consider, at the same time, its potential commercial value.

We can consider environmental benefits as given by the project itself; in fact, one of the main environmental benefits of building reuse is the retention of the original building’s “embodied energy”. The University of Bath defines embodied energy as the energy consumed by all of the processes associated with the production of a building, from the acquisition of natural resources to product delivery, including mining, manufacturing of materials and equipment, transport and administrative functions [

60]. By reusing buildings, their embodied energy is retained, making the project much more environmentally sustainable than an entirely new construction. At this point, the aim is to achieve three outputs at the same time: regeneration (as heritage conservation and enhancement), cultural consensus and commercial potentialities.

Regeneration intended as heritage conservation and enhancement is linked to the concept of culture as identification and conservation of the past, offering new uses [

49,

61,

62,

63,

64].

Cultural consensus is given by the involvement of the population according to the concordance and conformity of judgment and evaluation. It represents one of the elements that creates culture in a dynamic sense and aims to affirm new ideals and values by reworking social norms and convictions. It is functional to the maximization of the levels of community cohesion to obtain advantages and benefits by linking the elements of knowledge in full awareness. Commercial potentialities can be seen as an opportunity to gain revenues from a project that has strong implications in environmental, social and cultural dimensions.

5.1. Methodology Application and Analysis

For each of the three dimensions addressed—physical/cultural, social, economic—the analysis of scientific literature and case study analysis led to the identification of a class of requirements, which should be assumed as the focus of the reuse project. The identified classes of requirements (

Figure 2) are conservation of the building’s identity, cultural consensus and economic and financial sustainability. The goal was to extrapolate general rules in setting reuse choices that can be applied to new/different cases.

A list of general evaluation criteria derived from each class of requirements, and then key factors and indicators, have been specified. Using such indicators, evaluation criteria can be tested for their compliance in the observed case. This system, applied to a reuse project unanimously acknowledged to be successful, enables checking the appropriateness of the assumed valuation criteria and indicators. The validation of criteria and indicators in the London Postal Museum case study is a first step in establishing agreed guidelines for rail systems reuse project choices.

5.1.1. Physical/Cultural Dimension

The physical and cultural features of the area represent not only the constraint levels but also, and above all, a structural postulation of an integrated fruition system of the various resources. The basic elements of the effectiveness of best practice, which combines use and conservation purposes, can lead to the expansion of valorization strategies, through a hypothesis of the use of urban, extra-urban and rural node-stations to provide visitor services, to improve the knowledge of the sites and to facilitate monitoring and maintenance activities.

The table related to the physical-cultural transformations is determined by the reuse intervention lists criteria, key factors and indicators to verify the project’s ability to ensure the protection of the building’s identity (

Table 2). The list of indicators can be used both to evaluate ex post reuse work already completed and to evaluate and compare reuse project alternatives.

This study’s evaluation of the adequacy of design solutions related to the physical/cultural perspectives concern the following criteria: the protection of the perceptive-cultural, morphological-dimensional and material-constructive features of the building. For each criterion, several general factors have been identified and defined (sub-objectives) and subsequently translated into specific criteria. These are the indicators that describe the ability of the project to meet the objectives. Each indicator was then defined according to the nature of information we needed to collect and to the indicator direction (+/−) that specifies whether a high result constitutes a positive or negative element to achieve the original building protection objectives. Collected data were both qualitative and quantitative.

Within the aim of protecting perceptive-cultural features, the identified general factors are the following:

Transformations recognizability is the possibility of clearly distinguishing the new elements from the pre-existing ones. This is verified through the incidence of difference from the pre-existing construction systems, materials and finishes used to realize the elements of new construction.

Transformations reversibility is the possibility of removing the added elements or materials or to restore those that have been removed, in the hypothesis of bringing the building back to its original use or assigning it a new function. Reversibility is verified by the incidence of loss of material or removal of parts of the building that cannot be restored.

Transformations acceptability is the ability to ensure that variations of use destination and interventions on pre-existing elements are admissible for the client and for the direct, indirect and potential users of the building. Acceptability is verified by analysing what is preserved of the original features.

Respect for collective memory is the ability to guarantee that the transformations do not alter the recognizability of the asset as a representative element of the identity of social groups that ascribe symbolic values to it. Respect for the collective memory is evaluated according to the permanence of decorative elements, signs, plant components and equipment that characterized the original use.

Within the aim of protecting morphological-dimensional characters, the identified general factors are the following:

Protection of the features of geometric configuration of the building shell and preservation of aesthetic relations within the context is the ability to preserve the morphological, dimensional relationship and proportions of the building shell and its parts, in relation to the urban context. This factor is verified by examining the possible addition or removal of aboveground volumes or the impact of the transformations of the building shell.

Protection of the original dimensions of the building is the ability to not modify the size of the original building through the construction of new buildings. The protection of the original dimensions is verified by observing the construction of new volumes, detached from the pre-existing building.

Protection of the geometric configuration features of the interior spaces is the ability to preserve the shapes, dimensions and proportions of the internal spaces of the building. These features have specific perceptive-cultural values. This factor is verified by examining the internal spaces with specific values that have been divided or merged using systems that allow the perception of the original space articulation.

Within the aim of protecting material-constructive features, the identified general factors are the following:

Constructive logic preservation is the ability to protect the elements of the construction system and the relationships that bind them as proof of the material culture of a given historical moment or of the evolution of material culture over time. This factor is verified by considering the capacity of the reuse project to preserve the original construction system and its operating rules;

Technical elements conservation is the ability to guarantee the continuity of the current technical elements through the use of new compatible materials and products and of technological solutions that can reduce substitutions. This factor is verified according to the quantity of constructive elements that have preserved their functions after the reuse intervention.

Finishing materials preservation is the ability to guarantee the persistence of the present materials using new compatible materials and products and technological solutions that allow for minimal loss of material. This factor is verified according to the quantity of finishing elements that have preserved their functions and their original appearance.

Transformations compatibility is the opportunity to use new materials and techniques or change the elements or space configuration without damaging the building or accelerating the degradation process. This factor is verified by considering the number of carried out transformations using elements or materials that intensify the degradation of the pre-existing structure.

Transformations durability is the ability to prevent a rapid degradation process of the interventions. This factor is verified in relation to the durability of materials and components used for the transformations.

In order to evaluate the actual impact of the reuse intervention in relation to the defined evaluation criteria, information related to the pre-existing building system and to the transformations following the intervention, have been detected. The analysis was carried out by observing the following building elements:

vertical structural support (e.g., bearing walls, pillars, etc.): limited demolition of internal walls when there was limited historical interest; a new entrance way was created by making an opening in the existing structure; new fire escape exit;

roof and roof covering: no changes, as the station is within an underground space;

partitions: no changes, as there are no partitions;

slabs: partial and restricted to one area, demolition of a floor slab for the placement of a dirty water storage tank for toilets;

stairs/elevators: a new set of stairs was created from the entrance welcome space into the main depot below street level; an existing set of stairs into the main Royal Mail sorting office above were removed; a pedestrian platform lift was installed to enable step-free access;

horizontal distribution system (aisles, tunnels, etc.): no changes;

window frames: no changes, as there are no windows within the space;

door frames: replacement and addition of some doors, meeting fire regulations;

finishings (plaster, painting, flooring, etc.): minimal work, to comply with modern regulations;

other characterizing elements or equipment (e.g., clocks, post boxes, signage, etc.): equipment partial conservation; integration of some elements within the exhibition, including trains, control equipment and associated rail equipment; some trains used as set dressing around the route of the train ride;

outdoor spaces: no outdoor space; the courtyard in the main museum is used primarily for seating for the café and occasionally outside learning sessions or theatre performances.

Design choices were also examined:

materials and techniques used for the renovation interventions on the buildings (station and new building): concrete and plaster board installations where required; steel structures in structural work as required; the flooring was steel plate with rubberised flooring surface; due to being an underground space, materials have been chosen carefully to reduce fire load.

Overall, minimal interventions were made, especially to allow access for those with disabilities and to introduce fire exits and systems to comply with regulations. Fire detection and smoke extraction systems were also needed.

5.1.2. The Social and the Economic Dimensions

Today, new forms of collaboration among different subjects for the achievement of common objectives generate social welfare. Cultural consensus becomes the tool to promote life context regeneration interventions encouraged by new social innovation ideas such as products, services and models. Nonetheless, the interaction between social acceptances, intended as community, and socio-political acceptance and market acceptance is essential [

65].

Acceptance by key stakeholders and policy makers, communities’ trust towards a new project and consumers and investors and inter-firm acceptance are the basis for the successful outcome of a project. The proposed tables (

Table 3 and

Table 4) indicate levels of adaptability, admissibility of the project, investment in human capital and acceptance from an economic point of view.

The analysis of the two dimensions synthetizes the output given by data interpretation to define the impact of a reuse project and a sustainable management model. Sustainability is about integrating economic, environmental and social aspects, as well as integrating short-term and long-term aspects and consuming the income and not the capital [

66].

The first step was to identify a requirement class that identifies the focus to which general and specific criteria refer. For the social dimension, the requirement class is cultural consensus, and for the economic dimension, it is economic and financial sustainability.

General criteria represent the goals and each criterion has different key factors or subgoals. Specific criteria have been identified for each key factor describing how to calculate the indicator or specific factor. Specific factor (indicators) values are calculated on a percentage basis and reflect their weight. They describe the project’s ability to meet the objectives [

48].

For each indicator, the type of information required and the direction (+/−) were defined. The direction indicates whether a high result constitutes a positive or negative element for the achievement of the objectives. Collected data were both qualitative and quantitative.

For the social dimension, the general criteria are the following:

Bottom-up aggregation as positive (associations) or negative (NIMBY) interest in a project and museum fruition, both from a physical point of view and from the social inclusion of minority groups point of view, to estimate public interest level and possibility of use/fruition. This is verified by expected or carried out negative actions against the new project (e.g., NIMBY) and creation of social activities and services for minority groups.

Active involvement as creation of independently managed meeting places and common areas for citizens. This is verified by the creation/number of common activities for citizens and neighbourhood inhabitants in the museum.

Consensus as direct return from the new project’s functions or features such as benefits to a specific group of people. These can consist in the strenght given by connections encouraged by sharing common principles and judgements and by the perception of a common identity from the sense of belonging to the same community, by the estimation of social benefits, integration of advantages for citizens and maximization of cohesion levels. This is verified by direct advantages or benefits to citizens from the new museum project, social services interventions and expenses for the user base and number of industrial, commercial and residential users that decide to adopt a collective approach based on a smart management of resources deriving from the new project.

Spatial and temporal adaptability of the museum’s potential to be used by multiple categories of users at different times and the museum’s potential to be used by several categories of users at the same time, to estimate use by multiple consumers at different times and use by multiple consumers simultaneously. This is verified by the number of different users/visitors for the different attractions and the number of compatible functions.

Admissibility as making integrated services more attractive, decreasing the level of social distress, new opportunities for future generations, determining how much the population would be willing to pay to get the benefits from this new system or avoid a loss in its level of well-being, sharing transformation scenarios and the creation of the least possible amount of problems for individuals not directly involved in the new project. This is estimated by considering the promotion of the new project with other initiatives, opposition to societal malaise, maximization of intertemporal equity, willingness to pay, involvement in management and maximization of interlocal equity. This is verified by the number of additional services/attractions beyond the visit to the museum, a decrease in the level of dirt on the streets, a decrease in crime, amount of vandalism, amount of violence since the museum opened, the number of services guaranteed to future generations, how much citizens would be willing to pay to get the benefits of the museum and reuse of the station or avoid a loss in their level of well-being, participation of citizens in the decision-making process and if there are negative externalities.

Investment in human capital (knowledge) as economic opportunities, landscape enhancement, jobs as a percentage of the resident population and specialization and local and regional development, estimated by considering revitalization of the job market and promotion of professional development. This is verified by the presence of new jobs connected with the museum and station reuse as a percentage of the resident population and an increase in the number of workers with an apprenticeship contract for qualified labour.

For the economic dimension, the general criteria are the following:

Revenues as the total amount of inflows and positive cash flows phenomena, estimated by considering inflows and incentives. This is verified by revenue derived from the sale of museum tickets, gadgets/merchandising and the mail rail ride, income derived from the management of the coffee bar, incentives for construction works and incentives for the museum’s management.

Financial needs as negative cash flows phenomena/expenses, estimated by considering construction costs and management costs. This is verified by reconversion costs, employees costs, utilities costs, costs for outsourced services, ordinary maintenance costs, costs of goods, insurance costs, overheads and expenses for the use of third party assets.

5.2. Direct Analysis, the Interview

This research methodology includes key informant interviews that validate the model and offer suggestions on the reliability of the chosen parameters. For the analyzed case study, we interviewed Ms. Paola Barbarino, Trustee of The Postal Museum and Lauderdale House. The interview, comprising 11 questions, mainly focused on the funding process and model. The most important issue that emerged from the interview is that the funding model for the Postal Museum has been effective. The initial investment required to set up the museum up was only possible thanks to the vision and philanthropic support of many large donors. Funding sources included the Heritage Lottery Fund, corporate funding, trusts and foundations, other institutions and associations and private donors. The funding model’s goal was to allow the museum to be able to break even between ticket sales and other income, including regular fundraising, but the first year of operation went well beyond expectations, considering the annual number of visitors, which was 190,000 in the first year. The interview also shows evidence that the trustees are considering the wider impact to the community beyond their specific project from the outset.

Critical elements found in the funding process can be summarized as follows:

having the right human resources to fundraise;

building a case for support;

identifying a fundraising strategy (including possible channels of funding);

carrying out prospect research;

asking;

following up;

thanking, cultivating and reporting back;

repeating;

having a great database.

What also emerged from the key informant is that it is very difficult to import the funding model used for this museum in the UK to other countries. The museum is the product of a fortunate convergence of three factors:

the Post Office and Royal Mail backing the venture from the start both financially and from a management viewpoint (representatives of both organizations sit on the board);

the existence of the Heritage Lottery Fund of which, for example, there is no equivalent in Italy (Telethon being more similar in its grant-giving objectives to the Big Lottery Fund or Comic Relief);

the fortunate co-location of an important (but not so public-friendly) archive which needed a new home and a piece of fascinating railway/industrial heritage with the potential of attracting visitors.

The interview was also geared towards verifying the applicability of the reuse model examined as good practice in other contexts. In particular, a comparison with the Italian framework has been suggested. Whilst acknowledging that there are no constraints to a resource-finding system (donations) in Italy, the constraints are given by the legal nature of the role of trusts and trustees.

The Trust in Italy became operational in 1992, following the ratification of the Hague Convention of 1985, a multilateral treaty in which the signatory states established common provisions regarding the law applicable to trusts and their recognition. It is therefore a recognized legal institute in our country but, despite the numerous bills on the subject, our system is still lacking in its civil law. In addition, in Italy, the Trust is mainly used for the possession, management and conservation of heritage and in operations of generational transfer instead of philanthropic purposes.

In Italy, pursuant to art. 1 of Law Decree no. 83 of 31.5.2014, “Urgent provisions for the protection of cultural heritage, the development of culture and the revival of tourism”, converted with amendments into Law no. 106 of 29/07/2014 and subsequent amendments, a tax credit was introduced for liberal cash disbursements in support of culture and entertainment, the so-called Art Bonus, as support for patronage in favor of cultural heritage. Those who make liberal cash donations to support culture, as provided for by the law, will be able to enjoy important tax benefits in the form of tax credits.

In conclusion, the definition of management models, to be effective, must be differentiated in relation to the system of resources and constraints that exist at a local level.

6. Discussion

This proposed research hypothesis and model can be validated through a critical analysis of the results to verify if the methodology conceptually corresponds to the desired output. To analyse this point, we can answer two questions:

Generally, a simulation model of a complex system can be only approximate; nevertheless, our methodology was set up with the help of researchers, staff and trustees who work in the Postal Museum. The interaction with people that have direct access to data and that have knowledge of the simulated system contributes to model validation and reliability.

The first step was to define general indicators (general criteria, key factors, etc.) and then specific criteria depending on the case study.

The next step was to validate indicators applying the methodology to other contexts to test its transferability. This phase, which is ongoing, has already provided positive results from the first tests carried out on Italian cases of the same “main categories of new uses”. As an example, we report the results of the application of this method to the Roveto Bimmisca station, in Sicily, for which we tested the efficiency and sustainability of two alternative adaptive reuse hypotheses.

The two reviewed projects aim to reconvert the Noto-Pachino railway section to tourist facilities in the coastal strip of southeastern Sicily. Decommissioned—but not dismantled—in the 1990s, the Noto-Pachino railroad section is evidence of the productive history of the area. Built in the early 1930s, it was designated mainly for commercial use to transport fish and agricultural products to northern Sicily and, from there, to the mainland (

Figure 16).

The Roveto Bimmisca Station today plays a potential strategic role over tourism routes, as it is located in the Vendicari Natural Reserve, in a position connecting several settlements and sites of archaeological, natural and cultural interest. The two evaluation projects alternatives are based on different reuse approaches. Both projects aim to facilitate the interpretation and understanding of the sites and ensure a system of integrated services for users, while limiting transformations of the natural and built environment. The aim is the enhancement of local resources, counteracting the fragmentation of cultural attractions and facilitating accessibility. In both cases, visitor services (ticketing, luggage storage, catering, etc.) are established in the station building. However, in the two project hypotheses, the relationships with the pre-existing buildings are different. The first project alternative involves the refurbishment of the station building and warehouses with materials and construction techniques that resemble the pre-existing ones, with a faithful reestablishment of the construction elements according to the original design. In this case, the reconstruction of the warehouses building’s roofing allows the establishment of a rental centre for light electric vehicles. These could be used to visit the Vendicari Natural Reserve and to independently reach nearby archaeological sites and historical centres. In the second scenario, the collapsed roof is not reconstructed and an outdoor exhibition area is housed in the warehouse. In this case, the transformations that affect the station building are carried out with different materials and construction systems compared to those of the pre-existing building and with clearly recognizable contemporary architectural elements.

The three sets of criteria elicited from the case studies and, in particular, from the good practice of the London Postal Museum were used to carry out a multi-criteria analysis to evaluate the two alternative adaptive reuse solutions. The indicators are specified according to the peculiarities of the area and to the project’s goals. In this first validation phase, the evaluation was conducted by the research team itself, to be able to modify directly the criteria and indicators to fit the Italian context. After this, the validation will be extended to a larger number of cases and will be carried out with the involvement of local stakeholders in the multi-criteria evaluation process.

Figure 17 shows the results of the evaluation carried out using the AHP method [

67].

The output of this first phase is that the preferable project is the one that does not recreate the collapsed roofing and that emphasizes the building’s transformations with new architectural elements (Project B,

Figure 18). This result is affected both by the lower implementation costs and by its greater ability to preserve the identity of the site, highlighting pre-existing elements and promoting the reversibility of transformations.

The analysis highlights some key points that determine the quality of the results of the proposed methodology: (1) while validation allows the confirmation of adopted criteria, the given weight must be determined in relation to the site and to the aims we want to meet with the project; (2) the indicators may vary and be increased depending on the area of intervention and on the new purposes; (3) the choice of multi-criteria evaluation methodology will have to vary according to the type of considered indicators and, in particular, according to their qualitative and/or quantitative nature. Details of the assessment can be found in the

Supplementary Materials.

7. Conclusions

This research, as summarized in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2, provides criteria for assessing efficiency and sustainability in the adaptive reuse of abandoned or underused railway cultural heritage, according to the indicated sequence.

Criteria, key issues and indicators derive from the analysis of scientific literature and a preliminary examination of case studies, selected in relation to the five identified use categories. For the best practice of the London Postal Museum, the criteria have been verified through an interview with an expert informant. The developed methodology and the identified criteria can be used in combination with multi-criteria analysis methodologies for the validation of criteria and indicators in relation to different case studies. Furthermore, graduated weights can be paired to each criterion and for each case study, based on different development goals. In particular, integration with multi-expert involvement systems in the validation (e.g., with the Fuzzy Delphi method [

68]) can improve the reliability of the results.

Figure 19, which recalls audit schemes, shows that through the overview of the analysed best practice, its performances, findings and evaluations, we can achieve an extensive and replicable output. After analysing scope and objectives and summarizing a general overview including activities and strategy, the table shows performance for the first twelve months of the venue. Performances were considered higher than expectations, especially with respect to the Mail Rail, which was a great success. As far as findings are concerned, positive elements consider the preservation of cultural heritage and its governance, the support of the development of sustainable tourism, the establishment of hubs of cultural and creative industries, the creation of local employment, the facilitation of social inclusion within cities or territories, the fostering of territorial cohesion (e.g., local identity) and the improvement of quality of life.

Disruptive elements are connected to the more general neighbourhood regeneration and development policies rather than to the project itself. This case study is considered as part of the examined area only and for the collateral effects that could affect it. Social and urban requalification actions were promoted in the neighbourhood in recent years. A part of the museum and the station requalification, a new luxury apartment building development, is under construction right across the street from the Mail Ride and the Postal Museum. This enhancement can cause problems related to social exclusion issues, generating animosity and discontent within previous residents of the neighbourhood. They would not benefit from the new amenities offered by new constructions, emphasizing the fact that there are no new funding proposals for local council housing nor from the potential new luxury commercial activities that could be out of their reach. This could cause social challenges and concerns that would affect the whole area.

The evaluation and review column tells us the scores totaled by the different examined parameters, pointing out strengths and weaknesses.

The conclusions highlight the final output obtained by summarizing the key findings derived by the validation activity.

The Postal Museum can be also pictured in relation to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and its 17 goals that recognize that “ending poverty and other deprivations must go hand-in-hand with strategies that improve health and education, reduce inequality, and spur economic growth—all while tackling climate change and working to preserve our oceans and forests” (United Nations, n.d.).

Figure 20 indicates which requirements are accomplished by the project. The goals to consider are the following: goal 11, sustainable cities and communities; goal 17, partnerships to achieve the goal; and goal 4, quality education.

Reuse can be a propulsive factor in the productivity of urban and extra-urban areas, representing an element of attraction and promotion and an opportunity to promote the development of an area with the settlement of new activities.

Italy (railway heritage being public and given under concession), up to the present day, has made various efforts for the enhancement of cultural and landscape heritage, operating, however, without an intervention coordination process and with little success in involving private operators.

The system’s complexity and the scarcity of available financial resources are the main obstacles to the implementation of effective enhancement measures. First, the short duration of the concessions limits the attractiveness for private investors, not allowing them to obtain long-term profits and strategies. Second, the feasibility of enhancement actions is closely related to the identification of financial instruments and/or tax incentives for the advancement of the project itself and of its supply chain. Therefore, it is necessary to identify new models connected to strategies that broaden the choice among new uses for buildings, to increase the concession period and to incentivize private companies to deal with insufficient public resources.

If specific interventions can trigger widespread regeneration processes, with targeted investments, certainly a coherent system of punctual interventions can result in an amplified effect in terms of the exploitation of resources and the increase of urban and regional quality.

The creation of thematic cultural and environmental resource networks contributes, in the management phase, to optimising the cost of services and to increasing promotion and usability. The integrated offer of goods and services is a competitive advantage that strengthens local identity and brings benefits to local heritage through a system that can satisfy different use requirements [

69,

70,

71,

72].

The proposed methodology was implemented on the chosen case study and allowed for multi-faceted explorations of complex issues in their real-life settings. The results, driven by parameters and indicators for the social, economic and physical dimensions, highlight the importance of cultural consensus, innovation and economic, financial and cultural sustainability.

This research leads to the creation of a replicable assessment tool that orients towards a management model for development strategies through the creation of new synergies among existing cultural, social and economic resources. The positive effects of the implemented choices and strategies will be more impactful and effective the greater their ability to extend to the territorial scale.

The increase in physical quality and use of heritage resulting from the implementation of adaptive reuse projects, determined as a driver effect, attracts investments and raises interest in that particular area, which boosts local and regional competitiveness.

All this can be the trigger, including in countries where this practice is not common, to foster the interest of public and private investors. It can also encourage local governments to support initiatives with legal provisions and dedicated funding.

The creation of a goods and services network, connected with an adaptive reuse intervention, can offer diversification and promote goods that have no attraction capacity, giving value to the landmark.