Assessing the Anti-Corruption Disclosure Practices in the UK FTSE 100 Extractive Firms

Abstract

1. Introduction

RQ1. Can the deployment of reporting quality measures developed in the environmental reporting field enhance our understanding and interpretation of corruption-reporting quality and behavior?

RQ2. Does the use of these metrics provide consistent evidence that corporate ACD has responded to the introduction of the UK Bribery Act?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Anti-Corruption Disclosure Practices

“…develop Standards that bring transparency, accountability and efficiency to financial markets around the world. The Board’s work serves the public interest by fostering trust, growth and long-term financial stability in the global economy. The Conceptual Framework provides the foundation for Standards that: (a) contribute to transparency by enhancing the international comparability and quality of financial information, enabling investors and other market participants to make informed economic decisions….”(from SP1.5, page 6)

“SASB Standards identify the sustainability information that is financially material, which is to say material to understanding how an organization creates enterprise value. That information—also identified as ESG (environmental, social, and governance) information—is designed for users whose primary objective is to improve economic decisions.”

“The board should understand the views of the company’s other key stakeholders and describe in the annual report how their interests and the matters set out in section 172 of the Companies Act 2006 have been considered in board discussions and decision-making.”(Page 5. FRC, 2018)

2.2. Defining and Measuring Reporting Quality

2.3. Credibility of Assessing Reporting Disclosure and Its Quality

2.4. Measures of Assessing Reporting Quality

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Sample

3.2. Research Method: Content Analysis of Extractive Firms’ Annual Reports

3.3. Metrics of Corporate Disclosure

3.3.1. Standardized Quantity Index (SQNI)

3.3.2. Scope Index (SCI)

3.3.3. Total Quality Index (TQLI)

3.3.4. Weighted Quality Index (ACHI)

3.3.5. Weighted Quality Index (SHI)

3.3.6. Conclusions on Measures

4. Research Findings

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Research Question 1

4.2.1. Assessing ACD Using Unidimensional Metrics

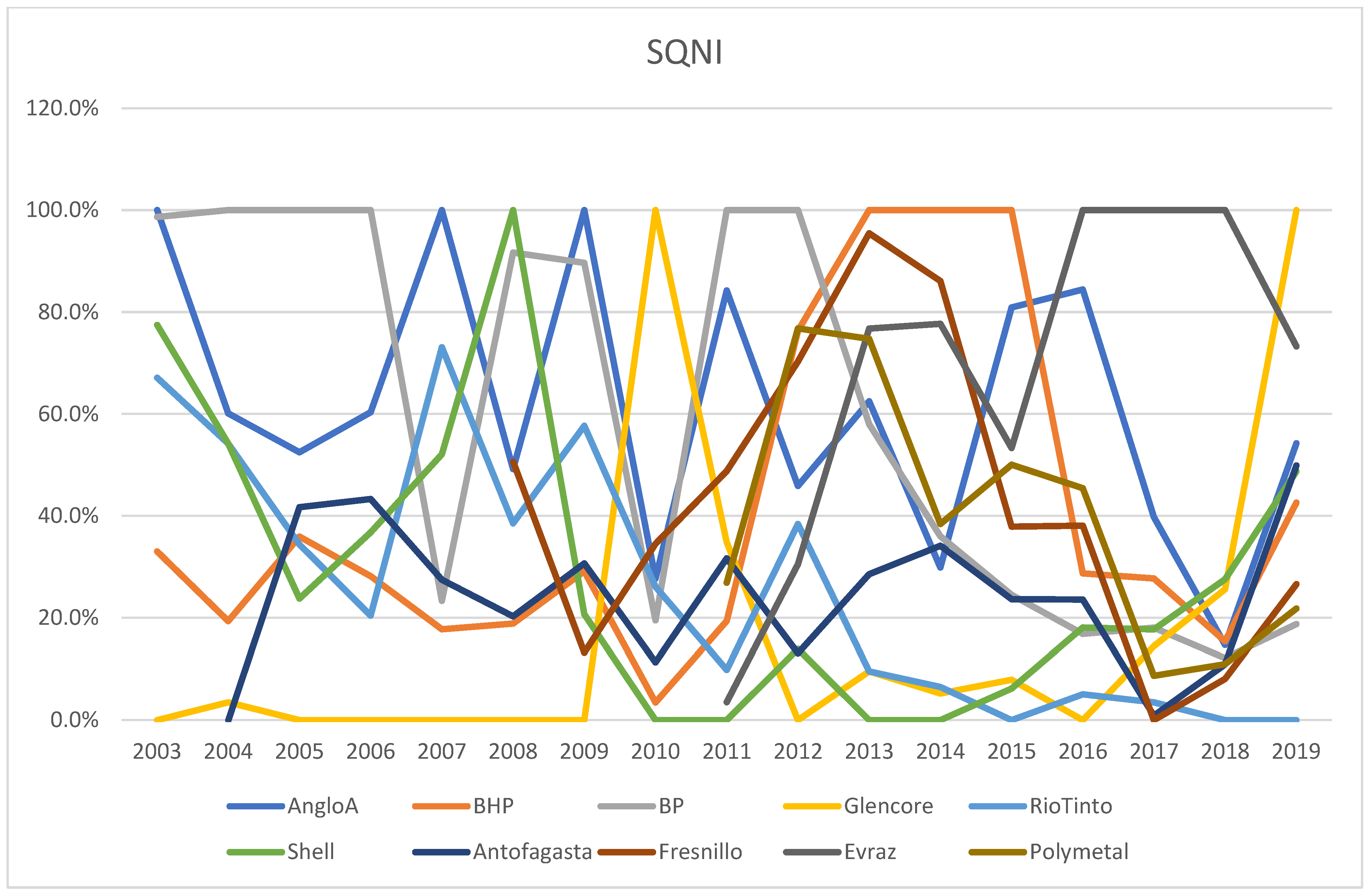

SQNI

SCI

4.2.2. Statistical Results of Multi-Dimensional Measures for UK Extractive Companies

Corporate Anti-Corruption Disclosure Findings (ACHI)

Corporate Anti-Corruption Disclosure Findings (SHI)

Corporate Anti-Corruption Disclosure Findings (TQLI)

4.2.3. Overview of Corporate Metric Results and Meaning

4.3. Research Question 2

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Category | Explanation | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Category 1: Proportionate Procedure | ||

| 1.1. Commitment to anti-corruption | Explores whether companies publicly announced that anti-corruption is a fundamental strategy for the company. | UK Bribery Act 2010 Transparency International UNCAC |

| 1.2. Bribery and corruption; Bribery Act and other relevant legislation | Aims to ensure that companies are also committed to fighting corruption and responding to the regulations. | UK Bribery Act 2010 Transparency International |

| 1.3. Prohibition of facilitation payments | Facilitation payments are bribes under section 1 of the Bribery Act as they provide an advantage, usually a small cash payment, to induce or reward a person, usually a public official, to give preferential treatment, or to refrain from or perform a task improperly. | UK Bribery Act 2010 Transparency International |

| 1.4. Effective internal anti-corruption control system | Aims to explore whether the anti-corruption program that takes place is under control and is monitored by a strong internal control system to ensure its effectiveness. | UK Bribery Act 2010 Transparency International |

| 1.5. Charitable donations | Charitable donations carry risks; they can be a conduit for corrupt payments. For example, a government official in negotiations with a business may disclose that they are on the board of a charitable organization and request a donation to be made to the charity, or a charity could be connected to a political party or a person with a decision-making function. Therefore, this item ensures that companies disclose their charitable donations. | UK Bribery Act 2010 Transparency International |

| 1.6. Political donations | Expenditures, cash or in kind, made directly or indirectly to a political party or its local branches, elected officials, or political candidates. Therefore, such donations may lead to obtaining an improper business benefit, such as winning a public contract or securing changes to laws or regulations. | UK Bribery Act 2010 Transparency International |

| 1.7. Prohibition of all forms of corruption, e.g., offering or receiving gifts, hospitality, or expenses | In the GRI Standards, ‘corruption includes practices such as bribery, facilitation payments, fraud, extortion, collusion, and money laundering. It also includes an offer or receipt of any gift, loan, fee, reward, or other advantage to or from any person as an inducement to do something that is dishonest, illegal, or a breach of trust in the conduct of the enterprise’s businesses.’ | UK Bribery Act 2010 Transparency International GRI |

| 1.8. Violations related to bribery and corruption | Requires companies to disclose any violations generated from corruption acts. | UK Bribery Act 2010 Transparency International |

| 1.9. Disclosure of ethical codes of conduct | Aims to ensure that companies are compliant with applying ethical/conduct codes to ensure their adherence to the external codes. | Transparency International |

| 1.10. Payments made to and received by governments based on EITI | Oil, gas, and mining companies, under the UK rules and as EITI members, are obligated to disclose any payments made or received by host countries. This ensures that such payment is not used for bribery. | EITI |

| Category 2: Top-level Commitment | ||

| 2.1. Zero tolerance of corruption | Company publicly ensures anti-corruption based on a policy of zero tolerance for corruption. The company prohibits bribery and will not tolerate its directors, management, employees, or third parties related to the company being involved with bribery, whether by offering, promising, soliciting, demanding, giving, or accepting bribes or behaving corruptly while expecting a bribe or an advantage. | UK Bribery Act 2010 Transparency International |

| 2.2. Board and management are overseeing the anti-bribery/anticorruption and program. | The board of directors or equivalent body is responsible for overseeing the company in which corruption/bribery is never acceptable and for ensuring that there is an effective design and implementation of a program to counter corruption. | UK Bribery Act 2010 Transparency International UNCAC WB OECD |

| 2.3. Anti-corruption on the board agenda | Anti-corruption holds a place in the board’s agenda, thus reflecting that the company is seriously taking action against corruption. | UK Bribery Act 2010 |

| 2.4. Consistent, relevant anti-bribery/anti-corruption laws in all relevant jurisdictions | Aims to ensure that companies are compliant with all relevant laws, including relevant anti-corruption laws. However, it is typical for a company to publicize its policy state to comply or be consistent with laws and regulations in all the countries in which the company and any subsidiaries operate. | UK Bribery Act 2010 Transparency International UNCAC WB OECD |

| 2.5. Employees dismissed or disciplined for corruption | Aims to ensure that action is taken by companies by disclosing the total number of confirmed incidents in which employees were dismissed or disciplined for corruption. | GRI WB OECD UNCAC |

| Category 3: Risk Assessment | ||

| 3.1. The board or management oversees the risk assessment process | Aims to ensure that the board or management are responsible for oversight and implementation of the risk assessment process and should require regular reports. A risk assessment process provides the company with a systematic view of the corruption risks, which can help them design detailed policies and procedures. | UK Bribery Act 2010

|

| 3.2. Corruption risk assessment | The risk assessment is established based on the risk of corruption and can help companies identify the scope of corruption risk. | UK Bribery Act 2010 Transparency International |

| 3.3. Risk assessment process continues based on the assessment and prioritization of the risk of corruption | UK Bribery Act 2010 Transparency International GRI | |

| Category 4: Communication, including Training | ||

| 4.1. Training on anti-corruption for directors and employees | Can help directors and employees become more committed to the program and provide employees with the skills required to address any situations they may encounter. | UK Bribery Act 2010 Transparency International GRI WB OECD UNCAC |

| 4.2. Percentage/number of employees trained | Aims to ensure that the company publishes information on the number/percentage of employees who are trained and have read the company’s anti-bribery guidelines. | UK Bribery Act 2010 Transparency International GRI |

| 4.3. Member anti-bribery/anti-corruption initiative | Aims to determine how many anti-corruption initiatives the companies obey and apply to their anti-corruption initiatives. | |

| Category 5: Due Diligence | ||

| 5.1. Anti-corruption and anti-bribery programs known to contractors, subcontractors, and suppliers | Aims to ensure that the company is vigorous and thorough in ensuring that its program is communicated to and endorsed by all its contractors and suppliers. | UK Bribery Act 2010 Transparency International |

| 5.2. Company avoids and terminates contractors and suppliers suspected of paying bribes | Presents a clear picture that companies are strict in their action of fighting corruption by avoiding dealing with contractors and suppliers who take or offer bribes. | UK Bribery Act 2010

|

| 5.3. Company monitors contractors and suppliers to ensure they have effective anti-corruption and anti-bribery programs | Proves that companies are dealing with contractors and suppliers who are obviously establishing programs to fight against corruption. | UK Bribery Act 2010 Transparency International |

| Category 6: Monitoring and Review | ||

| 6.1. External assurance of anti-corruption program effectiveness | Aims to obtain feedback from third parties to ensure the effectiveness and robustness of the program. | UK Bribery Act 2010

|

| 6.2. Audit committee, oversight of internal controls, financial reporting processes, and related functions, including countering corruption/bribery. | Aims to ensure that the audit committee makes an independent assessment of the adequacy of the program and discloses its findings in the annual report to shareholders. | UK Bribery Act 2010 Transparency International |

References

- Islam, M.A.; Dissanayake, T.; Dellaportas, S.; Haque, S. Anti-Bribery Disclosures: A Response to Networked Governance. Account. Forum 2018, 42, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanc, R.; Cho, C.H.; Sopt, J.; Branco, M.C. Disclosure Responses to a Corruption Scandal: The Case of Siemens AG. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 156, 545–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldaz Odriozola, M.; Álvarez Etxeberria, I. Determinants of Corporate Anti-Corruption Disclosure: The Case of the Emerging Economics. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose-Ackerman, S.; Palifka, B.J. Corruption and Government: Causes, Consequences, and Reform; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Global Corruption Report 2009: Corruption and the Private Sector. Available online: https://www.transparency.org/en/publications/global-corruption-report-2009 (accessed on 7 March 2023).

- Barkemeyer, R.; Preuss, L.; Lee, L. Corporate Reporting on Corruption: An International Comparison. Account. Forum 2015, 39, 349–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, D.; Dunfee, T.W. Fighting Corruption: A Principled Approach: The C Principles (Combating Corruption). Cornell Int. Law J. 2000, 33, 593. [Google Scholar]

- Kolstad, I.; Wiig, A. Is Transparency the Key to Reducing Corruption in Resource-Rich Countries? World Dev. 2009, 37, 521–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, D. Catalyzing Corporate Commitment to Combating Corruption. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 88, 781–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiscal Monitor, April 2019: Curbing Corruption. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/FM/Issues/2019/09/27/Fiscal-Monitor-April-2019-Curbing-Corruption-46532 (accessed on 7 March 2023).

- Le Billon, P. Natural Resources and Corruption in Post-War Transitions: Matters of Trust. Third World Q. 2014, 35, 770–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, S.J.; Hellman, N.; Ivanova, M.N. Extractive Industries Reporting: A Review of Accounting Challenges and the Research Literature. Abacus 2019, 55, 42–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robb, S.W.G.; Zarzeski, L.E.S.T. Nonfinancial Disclosures across Anglo-American Countries. J. Int. Account. Audit. Tax. 2001, 10, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finance Act 1999|ICAEW. Available online: https://www.icaew.com/technical/tax/budgets-and-legislation/finance-acts/finance-act-1999 (accessed on 7 March 2023).

- Improving Business Reporting—A Customer Focus: Meeting the Information Needs of Investors and Creditors: A Comprehensive Report. Available online: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1105&context=aicpa_comm (accessed on 7 March 2023).

- Lev, B.; Zarowin, P. The Boundaries of Financial Reporting and How to Extend Them. J. Account. Res. 1999, 37, 353–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, C.J.; Jones, C.L. The Usefulness of MD&A Disclosures in the Retail Industry. J. Account. Audit. Financ. 2004, 19, 361–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasseldine, J.; Salama, A.I.; Toms, J.S. Quantity versus Quality: The Impact of Environmental Disclosures on the Reputations of UK Plcs. Br. Account. Rev. 2005, 37, 231–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooks, J.; van Staden, C.J. Evaluating Environmental Disclosures: The Relationship between Quality and Extent Measures. Br. Account. Rev. 2011, 43, 200–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahan, S.F.; De Villiers, C.; Jeter, D.C.; Naiker, V.; Van Staden, C.J. Are CSR Disclosures Value Relevant? Cross-Country Evidence. Eur. Account. Rev. 2016, 25, 579–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, N.; Rigoni, U.; Orij, R.P. Corporate Governance and Sustainability Performance: Analysis of Triple Bottom Line Performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 149, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Peng, M.; Yin, J.; Xiu, Z. Does Local Governments’ Environmental Information Disclosure Promote Corporate Green Innovations? Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2022, 58, 3164–3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J. The ‘Subject’ of Corruption. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2015, 28, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimbro, M.B. A Cross-Country Empirical Investigation of Corruption and Its Relationship to Economic, Cultural, and Monitoring Institutions: An Examination of the Role of Accounting and Financial Statements Quality. J. Account. Audit. Financ. 2002, 17, 325–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khumawala, S.; Ramchand, L. Country Level Corruption and Frequency of Issue in the U.S. Market. J. Public Budg. Account. Financ. Manag. 2005, 17, 341–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everett, J.; Neu, D.; Rahaman, A.S. Accounting and the Global Fight against Corruption. Account. Organ. Soc. 2007, 32, 513–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfaya, A.; Bui, P. Exploring the Status Quo of Adopting the 17 UN SDGs in a Developing Country—Evidence from Vietnam. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Bribery Act 2010—Guidance. 2010. Available online: https://www.justice.gov.uk/downloads/legislation/bribery-act-2010-guidance.pdf (accessed on 7 March 2023).

- Helfaya, A.; Moussa, T. Do Board’s Corporate Social Responsibility Strategy and Orientation Influence Environmental Sustainability Disclosure? UK Evidence. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 1061–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfaya, A.; Whittington, M. Does Designing Environmental Sustainability Disclosure Quality Measures Make a Difference? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 525–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfaya, A.; Whittington, M.; Alawattage, C. Exploring the Quality of Corporate Environmental Reporting: Surveying Preparers’ and Users’ Perceptions. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2018, 32, 163–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Staden, C.J.; Hooks, J. A Comprehensive Comparison of Corporate Environmental Reporting and Responsiveness. Br. Account. Rev. 2007, 39, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-H. Does Size Matter? Evaluating Corporate Environmental Disclosure in the Australian Mining and Metal Industry: A Combined Approach of Quantity and Quality Measurement. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tuwaijri, S.A.; Christensen, T.E.; Hughes, K.E. The Relations among Environmental Disclosure, Environmental Performance, and Economic Performance: A Simultaneous Equations Approach. Account. Organ. Soc. 2004, 29, 447–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beretta, S.E.; Bozzolan, S. Quality Versus Quantity: The Case of Forward-Looking Disclosure. J. Account. Audit. Financ. 2007, 23, 333–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urquiza, F.B.; Abad Navarro, M.C.; Trombetta, M. Disclosure Indices Design: Does It Make a Difference? Rev. Contab. 2009, 12, 253–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M.A. Strategic Attributions of Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management: The Business Case for Doing Well by Doing Good! Sustain. Dev. 2022, 30, 409–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, F.; Ntim, C.G. Environmental Policy, Sustainable Development, Governance Mechanisms and Environmental Performance. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 415–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelger, C. The Return of Stewardship, Reliability and Prudence—A Commentary on the IASB’s New Conceptual Framework. Account. Eur. 2020, 17, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Andrew, J. Financialisation and the Conceptual Framework: An Update. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2022, 88, 102322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beattie, V.; McInnes, B.; Fearnley, S. A Methodology for Analysing and Evaluating Narratives in Annual Reports: A Comprehensive Descriptive Profile and Metrics for Disclosure Quality Attributes. Account. Forum 2004, 28, 205–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Amar, W.; Belgacem, I. Do Socially Responsible Firms Provide More Readable Disclosures in Annual Reports? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 1009–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, E.; Coluccia, D.; Fontana, S.; Solimene, S. Factors Influencing Corporate Environmental Disclosure. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2016, 25, 178–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalu, J.U.; Buang, A.; Aliagha, G.U. Determinants of Voluntary Carbon Disclosure in the Corporate Real Estate Sector of Malaysia. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 182, 519–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokuwaduge, C.S.D.S.; Heenetigala, K. Integrating Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Disclosure for a Sustainable Development: An Australian Study. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 438–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.H.; Zeng, S.X.; Shi, J.J.; Qi, G.Y.; Zhang, Z.B. The Relationship between Corporate Environmental Performance and Environmental Disclosure: An Empirical Study in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 145, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radu, C.; Francoeur, C. Does Innovation Drive Environmental Disclosure? A New Insight into Sustainable Development. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 893–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, C.H.; Roberts, R.W.; Patten, D.M. The Language of US Corporate Environmental Disclosure. Account. Organ. Soc. 2010, 35, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, R.; Kouhy, R.; Lavers, S. Constructing a Research Database of Social and Environmental Reporting by UK Companies. Account. Audit. Account. J. 1995, 8, 78–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unerman, J. Methodological Issues—Reflections on Quantification in Corporate Social Reporting Content Analysis. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2000, 13, 667–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beattie, V.; Jones, M.J. A Six-Country Comparison of the Use of Graphs in Annual Reports. Int. J. Account. 2001, 36, 195–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.C.; Campbell, D.; Shrives, P.J. Content Analysis in Environmental Reporting Research: Enrichment and Rehearsal of the Method in a British–German Context. Br. Account. Rev. 2010, 42, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, K.; Miles, S. Assessing Quality Assessment of Corporate Social Reporting: UK Perspectives. Account. Forum 2004, 28, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, P.M.; Palepu, K.G. Information Asymmetry, Corporate Disclosure, and the Capital Markets: A Review of the Empirical Disclosure Literature. J. Account. Econ. 2001, 31, 405–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormier, D.; Magnan, M.; Van Velthoven, B. Environmental Disclosure Quality in Large German Companies: Economic Incentives, Public Pressures or Institutional Conditions? Eur. Account. Rev. 2005, 14, 3–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toms, J.S. Firm Resources, Quality Signals and The Determinants of Corporate Environmental Reputation: Some UK Evidence. Br. Account. Rev. 2002, 34, 257–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, K. Reliability in Content Analysis.: Some Common Misconceptions and Recommendations. Hum. Comm. Res. 2004, 30, 411–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, T.; Kotb, A.; Helfaya, A. An Empirical Investigation of U.K. Environmental Targets Disclosure: The Role of Environmental Governance and Performance. Eur. Account. Rev. 2022, 31, 937–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, R.I.A.; Ezeani, E.; Gerged, A.M.; Usman, M.; Alqatamin, R.M. Does the Quality of Voluntary Disclosure Constrain Earnings Management in Emerging Economies? Evidence from Middle Eastern and North African Banks. Int. J. Account. Inf. Manag. 2020, 29, 91–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S.; Burritt, R. Contemporary Environmental Accounting: Issues, Concepts and Practice; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-1-351-28252-9. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.-T.; Liu, N.-C.; Lin, J.-W. Firms’ Adoption of CSR Initiatives and Employees’ Organizational Commitment: Organizational CSR Climate and Employees’ CSR-Induced Attributions as Mediators. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 140, 626–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, D. Intra- and Intersectoral Effects in Environmental Disclosures: Evidence for Legitimacy Theory? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2003, 12, 357–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aras, G.; Crowther, D. Corporate Sustainability Reporting: A Study in Disingenuity? J. Bus Ethics 2009, 87, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beattie, V.; Jones, M.J. The Use and Abuse of Graphs in Annual Reports: Theoretical Framework and Empirical Study. Account. Bus. Res. 1992, 22, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanc, R.; Islam, M.A.; Patten, D.M.; Branco, M.C. Corporate Anti-Corruption Disclosure: An Examination of the Impact of Media Exposure and Country-Level Press Freedom. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2017, 30, 1746–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.A.; Haque, S.; Dissanayake, T.; Leung, P.; Handley, K. Corporate Disclosure in Relation to Combating Corporate Bribery: A Case Study of Two Chinese Telecommunications Companies. Aust. Account. Rev. 2015, 25, 309–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.A.; Haque, S.; Gilchrist, D. NFPOs and Their Anti-Corruption Disclosure Practices. Public Money Manag. 2017, 37, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, C.; Gunawan, J.; Sawani, Y.; Rahmat, M.; Avelind Noyem, J.; Darus, F. A Comparative Study of Anti-Corruption Practice Disclosure among Malaysian and Indonesian Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Best Practice Companies. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 2896–2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, T.K.; Cahaya, F.R.; Joseph, C. Coercive Pressures and Anti-Corruption Reporting: The Case of ASEAN Countries. J. Bus Ethics 2021, 171, 495–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.; Pavelin, S. Factors Influencing the Quality of Corporate Environmental Disclosure. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2008, 17, 120–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackston, D.; Milne, M.J. Some Determinants of Social and Environmental Disclosures in New Zealand Companies. Account. Audit. Account. J. 1996, 9, 77–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanc, R.; Branco, M.C.; Patten, D.M. Cultural Secrecy and Anti-Corruption Disclosure in Large Multinational Companies. Aust. Account. Rev. 2019, 29, 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelon, G.; Pilonato, S.; Ricceri, F. CSR Reporting Practices and the Quality of Disclosure: An Empirical Analysis. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2015, 33, 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnabsha, A.; Abdou, H.A.; Ntim, C.G.; Elamer, A.A. Corporate Boards, Ownership Structures and Corporate Disclosures: Evidence from a Developing Country. J. Appl. Account. Res. 2018, 19, 20–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahim, A.; Fattah, T.A. Corporate Governance and Initial Compliance with IFRS in Emerging Markets: The Case of Income Tax Accounting in Egypt. J. Int. Account. Audit. Tax. 2015, 24, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, P.M.; Serafeim, G. An Analysis of Firms’ Self-Reported Anticorruption Efforts. Account. Rev. 2016, 91, 489–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’onza, G.; Brotini, F.; Zarone, V. Disclosure on Measures to Prevent Corruption Risks: A Study of Italian Local Governments. Int. J. Public Adm. 2017, 40, 612–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Company | Subsector | Founded | Years in Study | Market Cap (Oct 2020) (£Billion)) | Key Countries of Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BP | Oil and Gas | 1908 | 17 (2003–2019) | 54.340 B | UK/70 countries worldwide |

| Anglo American | Metals and Mining | 1917 | 17 (2003–2019) | 33.962 B | South Africa/15 countries |

| Rio Tinto | Metals and Mining | 1873 | 17 (2003–2019) | 93.758 B | Australia/35 countries |

| Shell | Oil and Gas | 1907 | 17 (2003–2019) | 100.464 B | Netherlands/More than 70 countries |

| Antofagasta | Metals and Mining | 1888 | 16 (2004–2019) | 14.231 B | Chile and the United States |

| Evraz | Steel | 1992 | 9 (2011–2019) | 7.325 B | Russian Federation, US, Canada, Czech Republic, Kazakhstan |

| Fresnillo | Metals and Mining | 2008 | 12 (2008–2019) | 7.929 B | Mexico |

| BHP | Metals and Mining | 1885 | 17 (2003–2019) | 159.591 B | Australia/20 countries |

| Polymetal | Metals and Mining | 1998 | 9 (2011–2019) | 7.842 B | Russia, Kazakhstan, Armenia |

| Glencore | Metals and Mining | 1974 | 17 (2003–2019) | 33.297 B | Switzerland/19 countries |

| Unidimensional (Quantity) Measures | Multidimensional (Quality) Measures | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized Quantity Index (SQNI) | Scope Index (SCI) | Total Quality Index (TQLI) | Weighted Quality Index (ACHI) | Weighted Quality Index (SHI) |

| Standardized quantity (percentage of disclosure compared to minimum and maximum of the sample) | Scope index (unweighted themes): number of anti-corruption themes disclosed (percentage of disclosed themes to the maximum possible number of themes in the disclosure checklist) | Quantity, themes, and richness of disclosure | [34] weighted index (based on the richness of themes disclosed) | [19] weighted index (themes weighed based on the richness of disclosure content) |

| SQNIi = (wordsi – min)/(max – min) | SCIi = (1/ni) ∑dj | TQLIi = 1/2 (SQNIi + RICHi) | ACHIi = Total quality score/occurrence score | SHIi = 1/ni ∑wjdj |

| Number of Words | Anglo American | BP | BHP | Glencore | RioTinto | Shell | Antofagasta | Fresnillo | Evraz | Polymetal | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003 | 955 | 943 | 352 | 55 | 659 | 752 | 619 | ||||

| 2004 | 725 | 1195 | 245 | 58 | 655 | 655 | 17 | 507 | |||

| 2005 | 438 | 782 | 318 | 58 | 307 | 230 | 360 | 356 | |||

| 2006 | 560 | 888 | 294 | 61 | 230 | 365 | 419 | 402 | |||

| 2007 | 763 | 227 | 188 | 64 | 575 | 428 | 256 | 357 | |||

| 2008 | 452 | 783 | 216 | 69 | 369 | 848 | 227 | 463 | 428 | ||

| 2009 | 914 | 827 | 318 | 73 | 558 | 247 | 331 | 184 | 432 | ||

| 2010 | 836 | 694 | 416 | 2089 | 808 | 356 | 552 | 954 | 838 | ||

| 2011 | 1831 | 2146 | 536 | 844 | 345 | 149 | 781 | 1123 | 219 | 686 | 866 |

| 2012 | 867 | 1696 | 1333 | 165 | 753 | 378 | 365 | 1241 | 632 | 1341 | 877 |

| 2013 | 1394 | 1312 | 2080 | 426 | 426 | 252 | 774 | 1997 | 1655 | 1618 | 1193 |

| 2014 | 944 | 1090 | 2617 | 356 | 387 | 232 | 1046 | 2285 | 2085 | 1148 | 1219 |

| 2015 | 2041 | 772 | 2471 | 398 | 220 | 359 | 752 | 1073 | 1420 | 1346 | 1085 |

| 2016 | 2138 | 771 | 1011 | 430 | 532 | 796 | 907 | 1200 | 2453 | 1349 | 1159 |

| 2017 | 1691 | 1159 | 1396 | 1071 | 802 | 1151 | 738 | 717 | 3166 | 930 | 1282 |

| 2018 | 1270 | 1166 | 1298 | 1712 | 674 | 1792 | 1117 | 1001 | 4729 | 1118 | 1588 |

| 2019 | 1730 | 835 | 1436 | 2885 | 361 | 1591 | 1620 | 1032 | 2210 | 912 | 1461 |

| Average | 1150 | 1017 | 972 | 636 | 509 | 622 | 641 | 1106 | 2063 | 1161 | 988 |

| Questions Answered (Max 26) | Anglo American | BHP | BP | Glencore | RioTinto | Shell | Antofagasta | Fresnillo | Evraz | Polymetal | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 3.5 | ||||

| 2004 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 1 | 3.3 | |||

| 2005 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 3.7 | |||

| 2006 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 2 | 5 | 8 | 2 | 4.6 | |||

| 2007 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 11 | 2 | 4.6 | |||

| 2008 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 9 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 4.8 | ||

| 2009 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 8 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 4.8 | ||

| 2010 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 8 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 11 | 6.8 | ||

| 2011 | 13 | 9 | 15 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 13 | 13 | 3 | 11 | 9.1 |

| 2012 | 14 | 12 | 14 | 2 | 7 | 4 | 11 | 13 | 10 | 12 | 9.9 |

| 2013 | 14 | 13 | 16 | 2 | 6 | 4 | 13 | 13 | 8 | 12 | 10.1 |

| 2014 | 9 | 14 | 13 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 15 | 9.1 |

| 2015 | 13 | 12 | 9 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 12 | 4 | 4 | 14 | 7.7 |

| 2016 | 13 | 8 | 12 | 3 | 6 | 7 | 16 | 7 | 11 | 12 | 9.5 |

| 2017 | 15 | 12 | 17 | 13 | 7 | 13 | 17 | 5 | 13 | 14 | 12.6 |

| 2018 | 16 | 15 | 16 | 13 | 9 | 15 | 18 | 11 | 19 | 14 | 14.6 |

| 2019 | 14 | 17 | 11 | 16 | 4 | 12 | 17 | 7 | 16 | 14 | 12.8 |

| Average | 9.2 | 8.4 | 9.8 | 4.8 | 6.1 | 6.4 | 9.0 | 8.5 | 10.4 | 13.1 | 8.6 |

| Observations | SQNI | SCI-Q | SCI-C | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 148 | 39.6% | 0.31 | 0.54 |

| Stdev | 148 | 32.8% | 0.19 | 0.31 |

| Min | 148 | 0.0% | 0.04 | 0.17 |

| Max | 148 | 100.0% | 0.69 | 1.00 |

| SQNI | SCI—Questions Based | SCI—Category Based | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Company | No of Years | Min | Max | Mean | Std. Dev | Min | Max | Mean | Std. Dev | Min | Max | Mean | Std. Dev |

| Anglo American | 17 | 14.7% | 100.0% | 61.5% | 26.5% | 0.12 | 0.62 | 0.36 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 1.00 | 0.65 | 0.35 |

| BHP | 17 | 3.5% | 100.0% | 40.9% | 32.1% | 0.12 | 0.65 | 0.32 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 1.00 | 0.44 | 0.31 |

| BP | 17 | 12.1% | 100.0% | 59.2% | 38.6% | 0.15 | 0.65 | 0.37 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 1.00 | 0.61 | 0.31 |

| Glencore | 17 | 0.0% | 100.0% | 17.7% | 32.5% | 0.08 | 0.62 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 1.00 | 0.39 | 0.28 |

| RioTinto | 17 | 0.0% | 73.1% | 26.1% | 25.0% | 0.08 | 0.35 | 0.23 | 0.07 | 0.17 | 0.67 | 0.41 | 0.19 |

| Shell | 17 | 0.0% | 100.0% | 29.2% | 29.0% | 0.08 | 0.62 | 0.25 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 1.00 | 0.39 | 0.28 |

| Antofagasta | 16 | 0.0% | 49.9% | 24.4% | 14.5% | 0.04 | 0.69 | 0.35 | 0.24 | 0.17 | 1.00 | 0.60 | 0.39 |

| Fresnillo | 12 | 0.0% | 95.5% | 42.5% | 29.8% | 0.12 | 0.69 | 0.41 | 0.20 | 0.17 | 1.00 | 0.63 | 0.26 |

| Evraz | 9 | 3.5% | 100.0% | 68.3% | 33.6% | 0.12 | 0.50 | 0.31 | 0.13 | 0.17 | 1.00 | 0.72 | 0.31 |

| Polymetal | 9 | 8.7% | 76.8% | 39.3% | 25.0% | 0.42 | 0.54 | 0.50 | 0.04 | 0.67 | 1.00 | 0.81 | 0.10 |

| Obs | TQLI | ACHI | SHI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 148 | 0.496 | 1.92 | 0.60 |

| Stdev | 148 | 0.276 | 0.37 | 0.36 |

| Min | 148 | 0.058 | 1.00 | 0.08 |

| Max | 148 | 1.173 | 3.00 | 1.73 |

| TQLI | ACHI | SHI | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Company | No of Years | Min | Max | Mean | Std. Dev | Min | Max | Mean | Std. Dev | Min | Max | Mean | Std. Dev |

| Anglo American | 17 | 0.35 | 0.86 | 0.63 | 0.18 | 1.38 | 2.33 | 1.85 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 1.27 | 0.65 | 0.37 |

| BHP | 17 | 0.20 | 0.96 | 0.52 | 0.29 | 1.69 | 2.25 | 1.98 | 0.17 | 0.23 | 1.27 | 0.63 | 0.37 |

| BP | 17 | 0.25 | 1.02 | 0.70 | 0.22 | 1.69 | 2.53 | 2.11 | 0.26 | 0.27 | 1.73 | 0.81 | 0.41 |

| Glencore | 17 | 0.06 | 1.04 | 0.27 | 0.31 | 1.00 | 2.50 | 2.03 | 0.51 | 0.08 | 1.08 | 0.37 | 0.36 |

| RioTinto | 17 | 0.06 | 0.62 | 0.33 | 0.17 | 1.17 | 2.17 | 1.75 | 0.37 | 0.12 | 0.69 | 0.41 | 0.15 |

| Shell | 17 | 0.10 | 0.75 | 0.39 | 0.24 | 1.00 | 2.50 | 1.93 | 0.33 | 0.08 | 1.23 | 0.49 | 0.33 |

| Antofagasta | 16 | 0.06 | 0.85 | 0.42 | 0.20 | 1.31 | 3.00 | 2.04 | 0.54 | 0.08 | 1.19 | 0.59 | 0.37 |

| Fresnillo | 12 | 0.17 | 0.85 | 0.47 | 0.23 | 1.00 | 2.33 | 1.68 | 0.35 | 0.27 | 0.88 | 0.52 | 0.22 |

| Evraz | 9 | 0.13 | 1.17 | 0.73 | 0.35 | 1.38 | 2.25 | 1.85 | 0.30 | 0.23 | 1.35 | 0.77 | 0.42 |

| Polymetal | 9 | 0.54 | 0.81 | 0.67 | 0.10 | 1.67 | 2.07 | 1.88 | 0.15 | 0.77 | 1.19 | 0.94 | 0.14 |

| Dimensions | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TLQI | Anglo American | 0.63 | 0.44 | 0.38 | 0.46 | 0.65 | 0.38 | 0.67 | 0.35 | 0.84 | 0.69 | 0.83 | 0.48 | 0.83 | 0.86 | 0.78 | 0.71 | 0.81 |

| BHP | 0.28 | 0.21 | 0.35 | 0.29 | 0.20 | 0.27 | 0.30 | 0.23 | 0.42 | 0.79 | 0.92 | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.43 | 0.70 | 0.71 | 0.85 | |

| BP | 0.67 | 0.71 | 0.81 | 0.83 | 0.25 | 0.71 | 0.70 | 0.33 | 1.02 | 1.02 | 0.83 | 0.62 | 0.47 | 0.58 | 0.96 | 0.85 | 0.57 | |

| Glencore | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.83 | 0.35 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.61 | 0.65 | 1.04 | |

| RioTinto | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0.36 | 0.29 | 0.62 | 0.44 | 0.62 | 0.42 | 0.24 | 0.44 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.06 | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.35 | 0.15 | |

| Shell | 0.54 | 0.31 | 0.25 | 0.53 | 0.70 | 0.75 | 0.26 | 0.19 | 0.12 | 0.22 | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.22 | 0.30 | 0.59 | 0.75 | 0.71 | |

| Antofagasta | 0.06 | 0.30 | 0.31 | 0.18 | 0.26 | 0.31 | 0.25 | 0.49 | 0.53 | 0.62 | 0.42 | 0.50 | 0.62 | 0.49 | 0.52 | 0.85 | ||

| Fresnillo | 0.39 | 0.24 | 0.44 | 0.69 | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.85 | 0.34 | 0.40 | 0.17 | 0.25 | 0.36 | ||||||

| Evraz | 0.13 | 0.42 | 0.60 | 0.73 | 0.44 | 0.94 | 1.12 | 1.17 | 0.98 | |||||||||

| Polymetal | 0.56 | 0.81 | 0.76 | 0.79 | 0.71 | 0.63 | 0.54 | 0.59 | 0.61 | |||||||||

| ACHI | Anglo American | 1.75 | 2.33 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 1.75 | 1.50 | 1.38 | 1.69 | 1.71 | 1.86 | 2.00 | 1.69 | 1.77 | 2.00 | 2.06 | 2.00 |

| BHP | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.25 | 2.00 | 2.20 | 1.89 | 1.75 | 1.69 | 1.71 | 1.92 | 1.88 | 2.23 | 2.20 | 1.94 | |

| BP | 2.25 | 2.20 | 2.29 | 2.43 | 1.75 | 2.17 | 2.17 | 2.40 | 1.86 | 1.93 | 1.69 | 1.77 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.53 | 2.38 | 2.09 | |

| Glencore | 2.50 | 2.50 | 2.50 | 2.50 | 2.50 | 2.50 | 2.50 | 2.13 | 1.50 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.67 | 2.08 | 1.92 | 1.75 | |

| RioTinto | 2.00 | 1.71 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.17 | 1.44 | 2.13 | 2.14 | 2.00 | 1.86 | 1.17 | 1.17 | 1.50 | 1.17 | 1.29 | 2.00 | 2.00 | |

| Shell | 2.00 | 1.00 | 2.33 | 2.25 | 1.91 | 1.86 | 2.00 | 2.50 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 1.75 | 1.67 | 2.00 | 1.57 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | |

| Antofagasta | 3.00 | 2.50 | 2.50 | 2.50 | 2.67 | 2.67 | 2.00 | 1.31 | 2.18 | 1.92 | 1.44 | 1.67 | 1.63 | 1.47 | 1.33 | 1.82 | ||

| Fresnillo | 2.33 | 1.80 | 1.27 | 1.77 | 1.69 | 1.56 | 2.10 | 1.75 | 1.43 | 1.80 | 1.00 | 1.71 | ||||||

| Evraz | 2.00 | 1.40 | 1.38 | 1.80 | 2.25 | 1.77 | 2.13 | 1.94 | 2.00 | |||||||||

| Polymetal | 2.00 | 1.83 | 1.67 | 2.07 | 1.71 | 1.75 | 1.86 | 2.00 | 2.00 | |||||||||

| SHI | Anglo American | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.23 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.27 | 0.35 | 0.42 | 0.85 | 0.92 | 1.04 | 0.65 | 0.85 | 0.88 | 1.15 | 1.27 | 1.08 |

| BHP | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.35 | 0.31 | 0.23 | 0.35 | 0.31 | 0.42 | 0.65 | 0.81 | 0.85 | 0.92 | 0.88 | 0.58 | 1.12 | 1.27 | 1.27 | |

| BP | 0.35 | 0.42 | 0.62 | 0.65 | 0.27 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.46 | 1.04 | 1.04 | 1.08 | 0.88 | 0.69 | 1.00 | 1.73 | 1.58 | 0.96 | |

| Glencore | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.65 | 0.35 | 0.23 | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.19 | 1.08 | 1.04 | 1.08 | |

| RioTinto | 0.31 | 0.46 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.65 | 0.58 | 0.38 | 0.50 | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.12 | 0.27 | 0.35 | 0.69 | 0.31 | |

| Shell | 0.31 | 0.08 | 0.27 | 0.69 | 0.88 | 0.50 | 0.31 | 0.38 | 0.23 | 0.31 | 0.27 | 0.19 | 0.38 | 0.42 | 1.00 | 1.23 | 0.92 | |

| Antofagasta | 0.12 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.08 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.38 | 0.65 | 0.92 | 0.96 | 0.50 | 0.77 | 1.00 | 0.96 | 0.92 | 1.19 | ||

| Fresnillo | 0.27 | 0.35 | 0.54 | 0.88 | 0.85 | 0.58 | 0.85 | 0.31 | 0.42 | 0.35 | 0.42 | 0.46 | ||||||

| Evraz | 0.23 | 0.54 | 0.42 | 0.69 | 0.35 | 0.88 | 1.23 | 1.35 | 1.23 | |||||||||

| Polymetal | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.77 | 1.19 | 0.92 | 0.81 | 1.00 | 1.08 | 1.00 |

| Total Period | SQNI | SCI-Q | SCI-Cat | SHI | ACHI | TQLI | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anglo American | 2 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 4 | 4 |

| BHP | 5 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| BP | 3 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Glencore | 10 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 3 | 10 | 9 |

| RioTinto | 8 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| Shell | 7 | 8 | 9 | 8 | 5 | 8 | 8 |

| Antofagasta | 9 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 7 | 6 |

| Fresnillo | 4 | 7 | 4 | 7 | 10 | 6 | 7 |

| Evraz | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 8 | 1 | 2 |

| Polymetal | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 3 | 3 |

| 2011–2019 | SQNI | SCI-Q | SCI-Cat | SHI | ACHI | TQLI | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anglo American | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 2 |

| BHP | 2 | 5 | 7 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| BP | 5 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Glencore | 8 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 7 | 9 | 9 |

| RioTinto | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Shell | 9 | 8 | 9 | 8 | 3 | 8 | 8 |

| Antofagasta | 7 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 9 | 6 | 6 |

| Fresnillo | 4 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 7 | 7 |

| Evraz | 1 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 5 |

| Polymetal | 6 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 4 |

| SQNI | SCI-Q | SCI-C | ACHI | SHI | TQLI (Revised) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SQNI | 1.000 | |||||

| SCI-Q | −0.283 | 1.000 | ||||

| SCI-C | −0.316 | 0.966 ** | 1.000 | |||

| ACHI | 0.130 | −0.673 * | −0.706 * | 1.000 | ||

| SHI | −0.348 | 0.983 ** | 0.961 ** | −0.659 * | 1.000 | |

| TQLI | −0.039 | 0.907 ** | 0.895 ** | −0.650 * | 0.902 ** | 1.000 |

| Measure | Before/After | N | Mean | Std. Deviation | Significance | Equal Var? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SQNI | 0 | 58 | 0.425 | 0.334 | ||

| 1 | 90 | 0.375 | 0.323 | 0.755 | Yes | |

| SCI-Q | 0 | 58 | 0.174 | 0.088 | ||

| 1 | 90 | 0.405 | 0.174 | 0.000 *** | NO | |

| SCI-C | 0 | 58 | 0.275 | 0.169 | ||

| 1 | 90 | 0.712 | 0.262 | 0.000 *** | NO | |

| SHI | 0 | 58 | 0.354 | 0.164 | ||

| 1 | 90 | 0.753 | 0.369 | 0.000 *** | NO | |

| ACHI | 0 | 58 | 2.12 | 0.368 | ||

| 1 | 90 | 1.79 | 0.301 | 0.153 | Yes | |

| TQLI | 0 | 58 | 0.390 | 0.214 | ||

| 1 | 90 | 0.565 | 0.289 | 0.008 *** | NO |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ghazwani, M.; Whittington, M.; Helfaya, A. Assessing the Anti-Corruption Disclosure Practices in the UK FTSE 100 Extractive Firms. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5155. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065155

Ghazwani M, Whittington M, Helfaya A. Assessing the Anti-Corruption Disclosure Practices in the UK FTSE 100 Extractive Firms. Sustainability. 2023; 15(6):5155. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065155

Chicago/Turabian StyleGhazwani, Musa, Mark Whittington, and Akrum Helfaya. 2023. "Assessing the Anti-Corruption Disclosure Practices in the UK FTSE 100 Extractive Firms" Sustainability 15, no. 6: 5155. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065155

APA StyleGhazwani, M., Whittington, M., & Helfaya, A. (2023). Assessing the Anti-Corruption Disclosure Practices in the UK FTSE 100 Extractive Firms. Sustainability, 15(6), 5155. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065155