The Social Perception of Autonomous Delivery Vehicles Based on the Stereotype Content Model

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Social Acceptability of Technological Devices

2.2. Social Perception of Devices and Their Connection to Different User Groups

2.3. Stereotypes

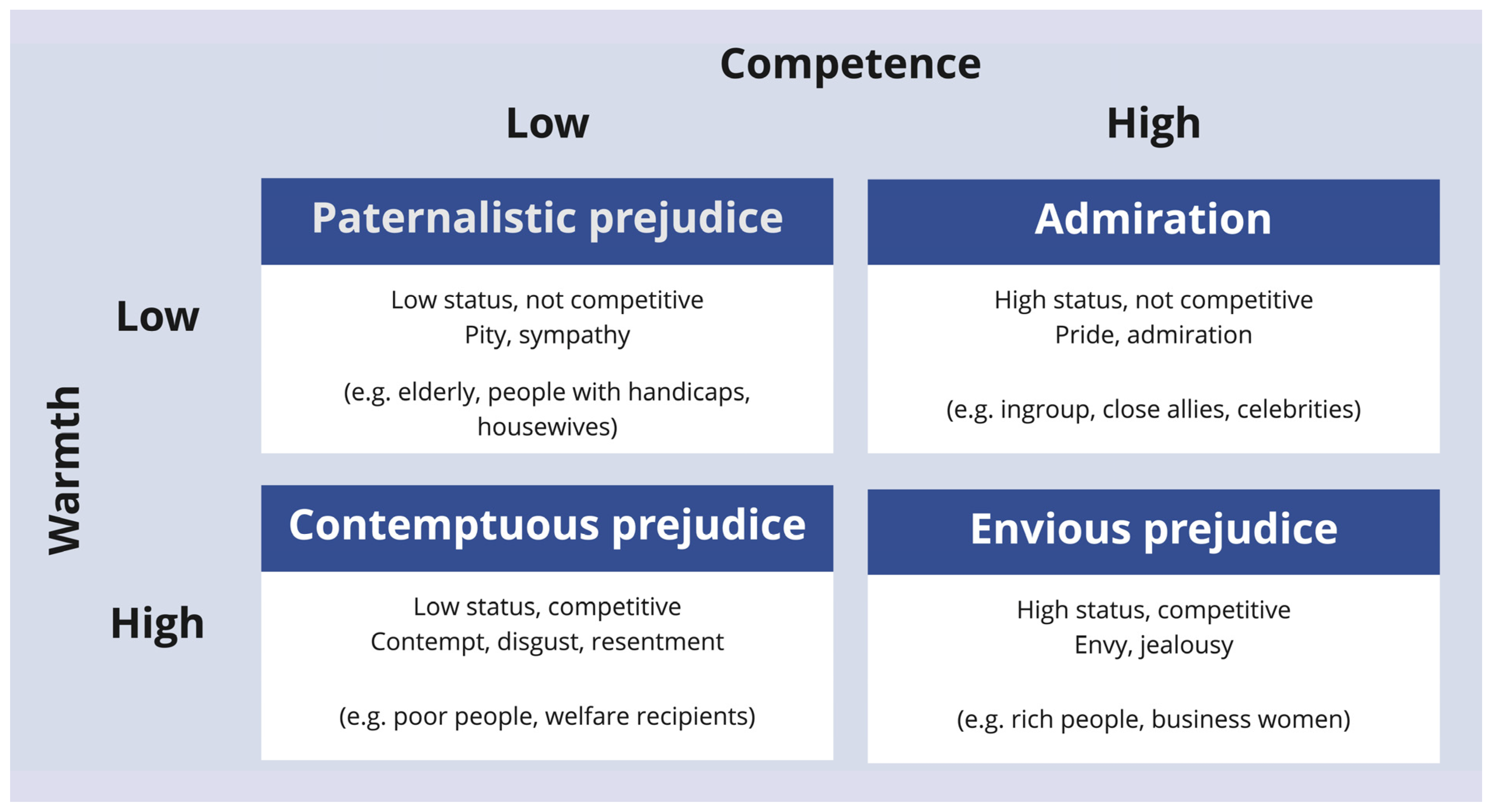

2.4. The Stereotype Content Model

2.5. Gender as a Source of Stereotypes

2.6. The SCM and the Perception of Technological Devices

2.7. The Perception of Autonomous Delivery Vehicles

2.8. Research Questions and Hypotheses

3. Method

3.1. Design

3.2. Materials

3.3. Participants

3.4. Survey Procedure

4. Results

4.1. Stereotypical Rating of Different Social Groups

4.2. Aggregation of Data

4.3. Analysis of Aggregated Data

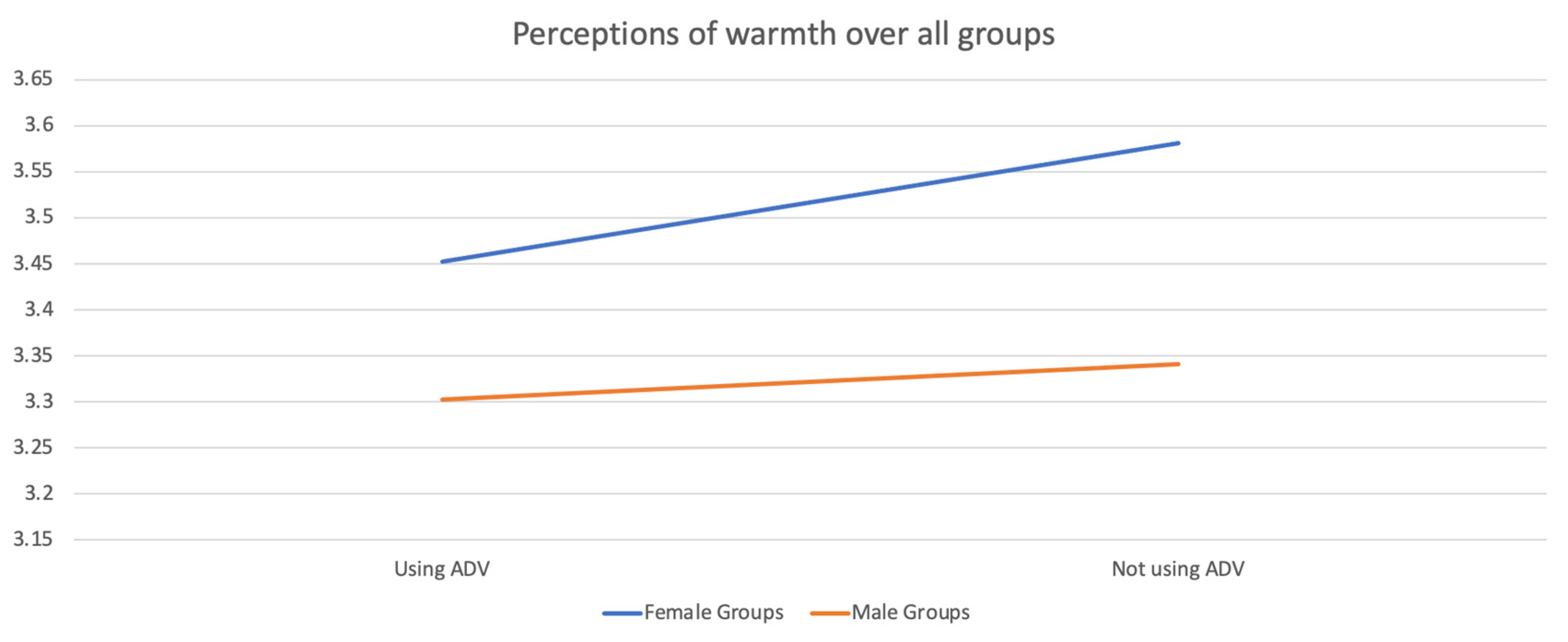

4.3.1. Warmth

- N = sample size

- F = F statistic/F value (degrees of freedom and residual degrees of freedom are in brackets)

- p = probability of error

- M = mean value

- SD = standard deviation

4.3.2. Competence

4.3.3. Ingroup Favoritism

4.4. Analysis of the Influence of Gender and Autonomous Vehicle Use on the Perception of Different Social Groups

4.4.1. Social Group 1: Women and Men

4.4.2. Social Group 2: Physicians

4.4.3. Social Group 3: Homemakers

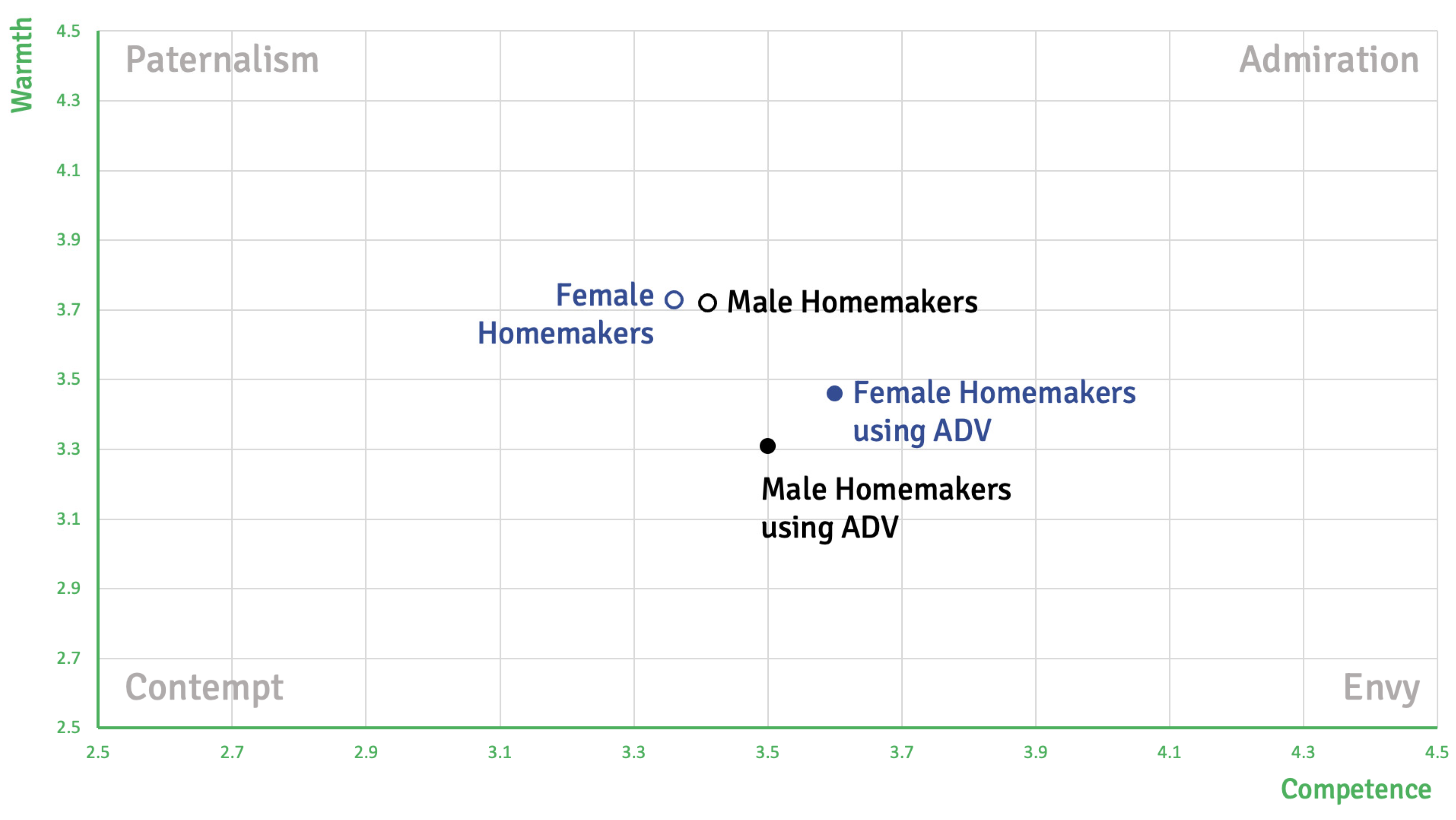

4.4.4. Social Group 4: College Students

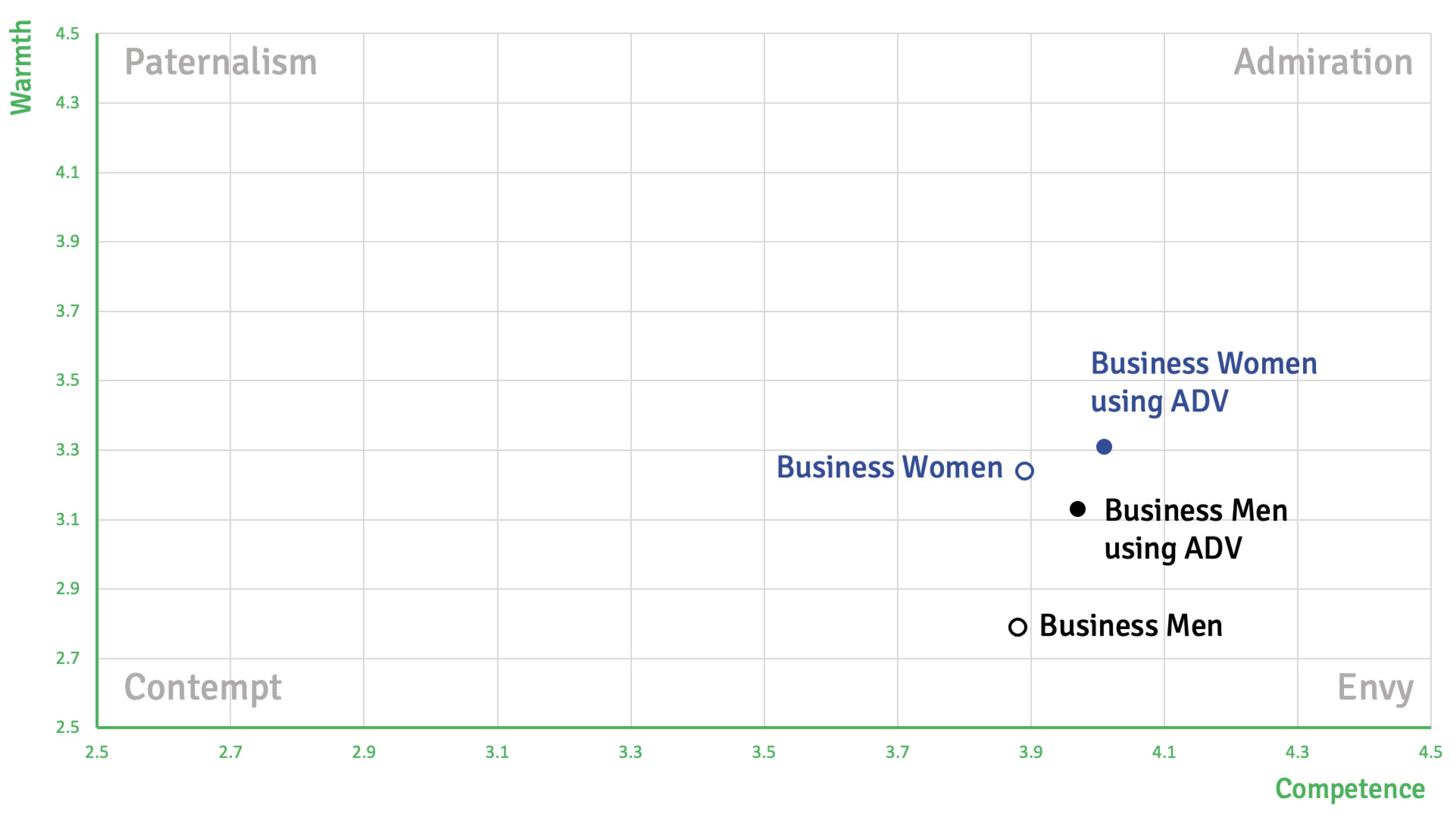

4.4.5. Social Group 5: Business Women/Men

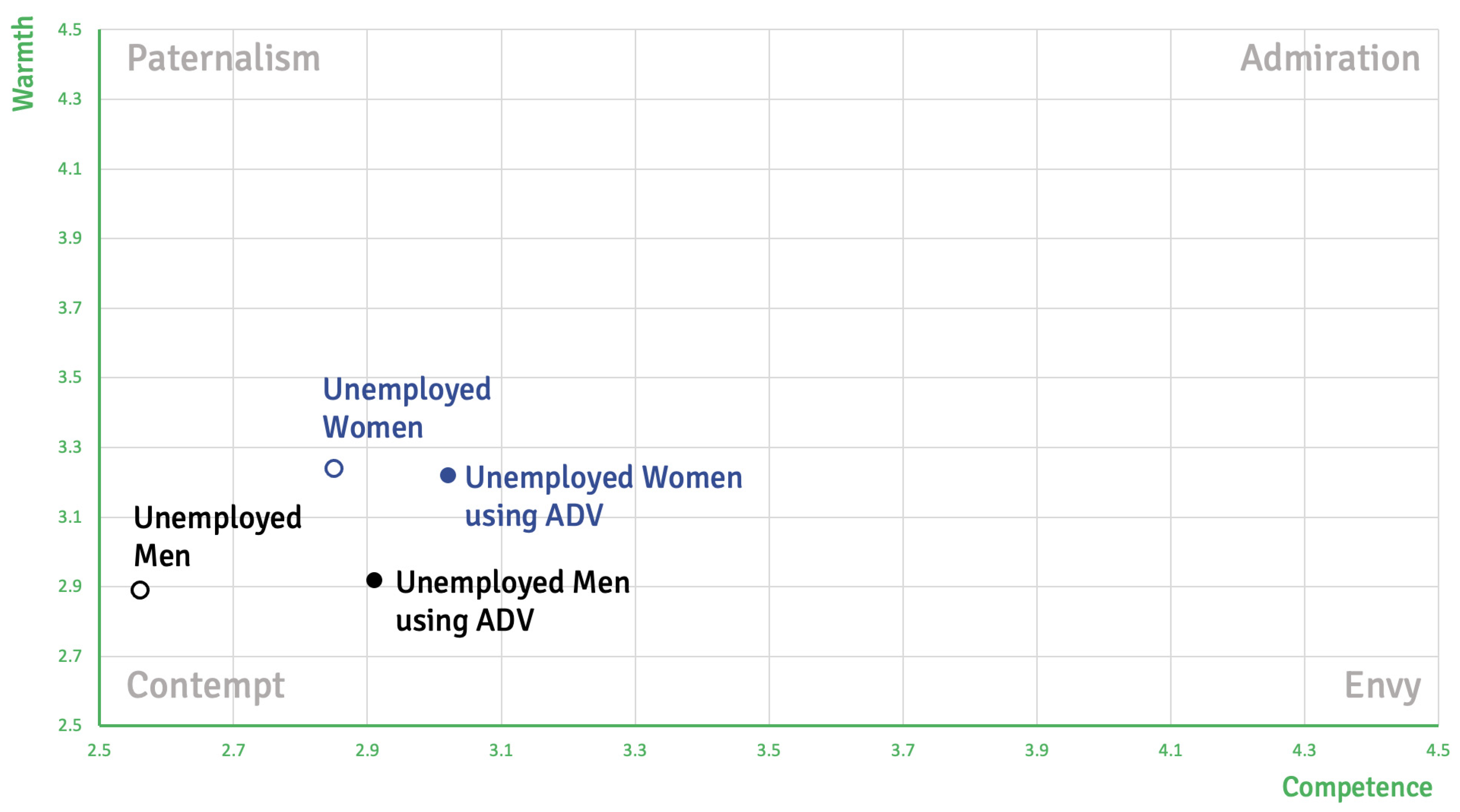

4.4.6. Social Group 6: Unemployed Women/Men

4.4.7. Social Group 7: Women/Men with Handicaps

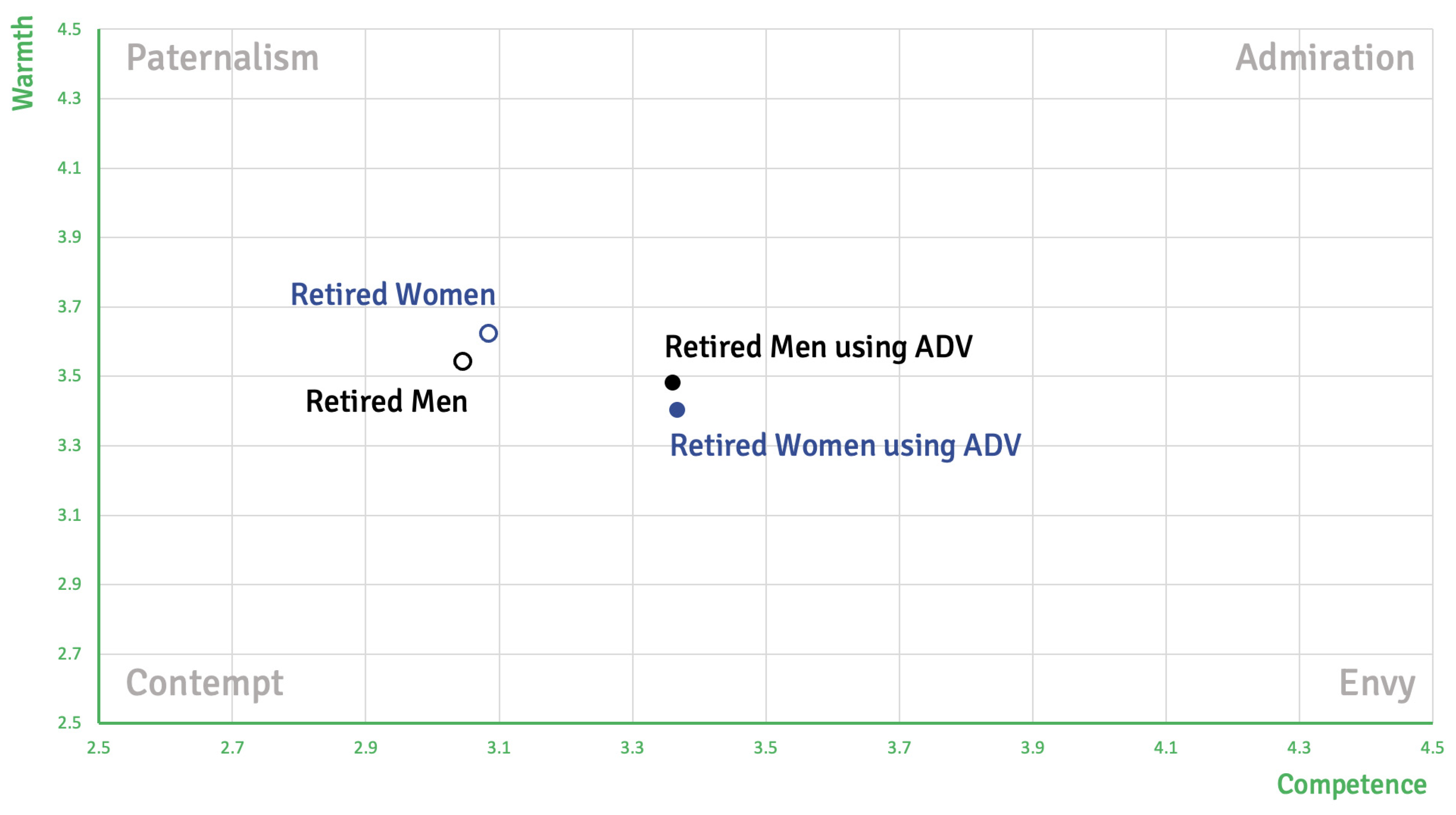

4.4.8. Social Group 8: Retired Women/Men

4.5. General Attitude towards Autonomous Delivery Vehicles

5. Discussion

6. Limitations and Future Work

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. List of All Groups Used in the Study Described as “Using Autonomous Delivery Vehicles (ADV)” or Not Using Autonomous Delivery Vehicles (ADV) in German

| 1 Männer im Umgang mit selbstfahrenden und selbststeuernden Lieferfahrzeugen |

| 2 Männer |

| 3 Frauen im Umgang mit selbstfahrenden und selbststeuernden Lieferfahrzeugen |

| 4 Frauen |

| 5 Ärzte im Umgang mit selbstfahrenden und selbststeuernden Lieferfahrzeugen |

| 6 Ärzte |

| 7 Ärztinnen im Umgang mit selbstfahrenden und selbststeuernden Lieferfahrzeugen |

| 8 Ärztinnen |

| 9 Hausfrauen im Umgang mit selbstfahrenden und selbststeuernden Lieferfahrzeugen |

| 10 Hausfrauen |

| 11 Hausmänner im Umgang mit selbstfahrenden und selbststeuernden Lieferfahrzeugen |

| 12 Hausmänner |

| 13 Studenten im Umgang mit selbstfahrenden und selbststeuernden Lieferfahrzeugen |

| 14 Studenten |

| 15 Studentinnen im Umgang mit selbstfahrenden und selbststeuernden Lieferfahrzeugen |

| 16 Studentinnen |

| 17 Geschäftsmänner im Umgang mit selbstfahrenden und selbststeuernden Lieferfahrzeugen |

| 18 Geschäftsmänner |

| 19 Geschäftsfrauen im Umgang mit selbstfahrenden und selbststeuernden Lieferfahrzeugen |

| 20 Geschäftsfrauen |

| 21 arbeitslosen Frauen im Umgang mit selbstfahrenden und selbststeuernden Lieferfahrzeugen |

| 22 arbeitslosen Frauen |

| 23 arbeitslosen Männer im Umgang mit selbstfahrenden und selbststeuernden Lieferfahrzeugen |

| 24 arbeitslosen Männer |

| 25 Männer mit Handicap im Umgang mit selbstfahrenden und selbststeuernden Lieferfahrzeugen |

| 26 Männer mit Handicap |

| 27 Frauen mit Handicap im Umgang mit selbstfahrenden und selbststeuernden Lieferfahrzeugen |

| 28 Frauen mit Handicap |

| 29 Rentner im Umgang mit selbstfahrenden und selbststeuernden Lieferfahrzeugen |

| 30 Rentner |

| 31 Rentnerinnen im Umgang mit selbstfahrenden und selbststeuernden Lieferfahrzeugen |

| 32 Rentnerinnen |

Appendix A.2. A Short Version the SCM-Scale Based on Cuddy, Fiske & Glick [16,22] and Asbrock [100] (Translated by the Authors)

- Wie kompetent sind nach Ansicht der Gesellschaft <Gruppennamen (im Umgang mit selbststeuernden und selbstfahrenden Lieferfahrzeugen)>

- 2.

- Wie eigenständig sind nach Ansicht der Gesellschaft <Gruppennamen (im Umgang mit selbststeuernden und selbstfahrenden Lieferfahrzeugen

- 3.

- Wie konkurrenzfähig sind nach Ansicht der Gesellschaft <Gruppennamen (im Umgang mit selbststeuernden und selbstfahrenden Lieferfahrzeugen)>

- Wie warmherzig sind nach Ansicht der Gesellschaft <Gruppennamen (im Umgang mit selbststeuernden und selbstfahrenden Lieferfahrzeugen)>

- 2.

- Wie sympathisch sind nach Ansicht der Gesellschaft <Gruppennamen (im Umgang mit selbststeuernden und selbstfahrenden Lieferfahrzeugen)>

- 3.

- Wie freundlich sind nach Ansicht der Gesellschaft <Gruppennamen (im Umgang mit selbststeuernden und selbstfahrenden Lieferfahrzeugen)>

References

- Koelle, M.; Boll, S.; Olsson, T.; Williamson, J.; Profita, H.; Kane, S.; Mitchell, R. (Un) Acceptable!?! Re-thinking the Social Acceptability of Emerging Technologies. In Proceedings of the Extended Abstracts of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 21–26 April 2018; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, J. Usability Engineering; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Koelle, M.; Ananthanarayan, S.; Boll, S. Social acceptability in HCI: A survey of methods, measures, and design strategies. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 25–30 April 2020; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Schwind, V.; Deierlein, N.; Poguntke, R.; Henze, N. Understanding the Social Acceptability of Mobile Devices Using the Stereotype Content Model. In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Glasgow, UK, 4–9 May 2019; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, E. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life; Doubleday: Garden City, NY, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Shinohara, K.; Wobbrock, J.O. In the shadow of misperception: Assistive technology use and social interactions. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 7–12 May 2011; pp. 705–714. [Google Scholar]

- Koelle, M.; Kranz, M.; Möller, A. Don’t look at me that way! understanding user attitudes towards data glasses usage. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services, Copenhagen, Denmark, 24–27 August 2015; pp. 362–372. [Google Scholar]

- Koelle, M.; El Ali, A.; Cobus, V.; Heuten, W.; Boll, S.C. All about acceptability? Identifying factors for the adoption of data glasses. In Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Denver, CO USA, 6–11 May 2017; pp. 295–300. [Google Scholar]

- Profita, H.P. Designing wearable computing technology for acceptability and accessibility. SIGACCESS Access. Comput. 2016, 114, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwind, V.; Reinhardt, J.; Rzayev, R.; Henze, N.; Wolf, K. Virtual reality on the go? A study on social acceptance of vr glasses. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services Adjunct, Barcelona, Spain, 3–6 September 2018; pp. 111–118. [Google Scholar]

- Schwind, V.; Henze, N. Anticipated User Stereotypes Systematically Affect the Social Acceptability of Mobile Devices. In Proceedings of the 11th Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction: Shaping Experiences, Shaping Society, Tallinn, Estonia, 25–29 October 2020; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, N.; Gilbert, S. The WEAR scale: Developing a measure of the social acceptability of a wearable device. In Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, San Jose, CA, USA, 7–12 May 2016; pp. 2864–2871. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, K.; Schmidt, A.; Bexheti, A.; Langheinrich, M. Lifelogging: You’re wearing a camera? IEEE Pervasive Comput. 2014, 13, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Profita, H.; Albaghli, R.; Findlater, L.; Jaeger, P.; Kane, S.K. The AT effect: How disability affects the perceived social acceptability of head-mounted display use. In Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, San Jose, CA, USA, 7–12 May 2016; pp. 4884–4895. [Google Scholar]

- Pohl, D.; de Tejada Quemada, C.F. See what I see: Concepts to improve the social acceptance of HMDs. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Virtual Reality (VR), Greenville, SC, USA, 9–23 March 2016; pp. 267–268. [Google Scholar]

- Cuddy, A.J.; Fiske, S.T.; Glick, P. The BIAS map: Behaviors from intergroup affect and stereotypes. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 92, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fiske, S.T.; Xu, J.; Cuddy, A.C.; Glick, P. (Dis) respecting versus (dis) liking: Status and interdependence predict ambivalent stereotypes of competence and warmth. J. Soc. Issues 1999, 55, 473–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaska, V.; Tsiakas, K.; Giakoumis, D.; Kostavelis, I.; Folinas, D.; Gasteratos, A.; Tzovaras, D. A Viewpoint on the Challenges and Solutions for Driverless Last-Mile Delivery. Machines 2022, 10, 1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckes, T. Geschlechterstereotype: Von Rollen, Identitäten und Vorurteilen. In Handbuch Frauen- und Geschlechterforschung; Becker, R., Kortendiek, B., Eds.; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2008; pp. 171–182. [Google Scholar]

- Cuddy, A.J.; Fiske, S.T.; Glick, P. When professionals become mothers, warmth doesn’t cut the ice. J. Soc. Issues 2004, 60, 701–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuddy, A.; Fiske, S.; Glick, P. Warmth and competence as universal dimensions of social perception: The stereotype content model and the BIAS map. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 40, 61–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiske, S.; Cuddy, A.; Glick, P.; Xu, J. A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 82, 878–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bye, H.H.; Solianik, V.V.; Five, M.; Agai, M.S. Stereotypes of Women and Men Across Gender Subgroups. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 881418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frischknecht, R. A social cognition perspective on autonomous technology. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 122, 106815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbanhawi, M.; Simic, M.; Jazar, R. In the passenger seat: Investigating ride comfort measures in autonomous cars. IEEE Intell. Transp. Syst. Mag. 2015, 7, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordhoff, S.; de Winter, J.; Payre, W.; Van Arem, B.; Happee, R. What impressions do users have after a ride in an automated shuttle? An interview study. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2019, 63, 252–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ranieri, L.; Digiesi, S.; Silvestri, B.; Roccotelli, M. A review of last mile logistics innovations in an externalities cost reduction vision. Sustainability 2018, 10, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kapser, S.; Abdelrahman, M.; Bernecker, T. Autonomous delivery vehicles to fight the spread of COVID-19–How do men and women differ in their acceptance? Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2021, 148, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapser, S.; Abdelrahman, M. Acceptance of autonomous delivery vehicles for last-mile delivery in Germany–Extending UTAUT2 with risk perceptions. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2020, 111, 210–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsden, N.; Bernecker, T.; Zöllner, R.; Sußmann, N.; Kapser, S. BUGA: Log–A real-world laboratory approach to designing an automated transport system for goods in Urban Areas. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Engineering, Technology and Innovation (ICE/ITMC), Stuttgart, Germany, 17–20 June 2018; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Sehrt, J.; Braams, B.; Henze, N.; Schwind, V. Social Acceptability in Context: Stereotypical Perception of Shape, Body Location, and Usage of Wearable Devices. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2022, 6, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VandenBos, G.R. APA Dictionary of Psychology; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Montero, C.S.; Alexander, J.; Marshall, M.T.; Subramanian, S. Would you do that? Understanding social acceptance of gestural interfaces. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Human Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services, Lisbon, Portugal, 7–10 September 2010; pp. 275–278. [Google Scholar]

- Avila Soto, M.; Funk, M. Look, a guidance drone! assessing the social acceptability of companion drones for blind travelers in public spaces. In Proceedings of the 20th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility, Galway, Ireland, 22–24 October 2018; pp. 417–419. [Google Scholar]

- Taniberg, A.; Botin, L.; Stec, K. Context of use affects the social acceptability of gesture interaction. In Proceedings of the 10th Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, Oslo, Norway, 29 September–3 October 2018; pp. 731–735. [Google Scholar]

- Alallah, F.; Neshati, A.; Sakamoto, Y.; Hasan, K.; Lank, E.; Bunt, A.; Irani, P. Performer vs. observer: Whose comfort level should we consider when examining the social acceptability of input modalities for head-worn display? In Proceedings of the 24th ACM Symposium on Virtual Reality Software and Technology, Tokyo, Japan, 28 November–1 December 2018; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F.D. A Technology Acceptance Model for Empirically Testing New End-User Information Systems: Theory and Results. Ph.D. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra, Y.; Galletta, D.F. Extending the technology acceptance model to account for social influence: Theoretical bases and empirical validation. In Proceedings of the 32nd Annual Hawaii International Conference on Systems Sciences, Maui, HI, USA, 5–8 January 1999; p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G. Why don’t men ever stop to ask for directions? Gender, social influence, and their role in technology acceptance and usage behavior. MIS Q. 2000, 24, 115–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rico, J.; Brewster, S. Usable gestures for mobile interfaces: Evaluating social acceptability. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Atlanta, GA, USA, 10–15 April 2010; pp. 887–896. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, Y.-T.; Jylhä, A.; Orso, V.; Gamberini, L.; Jacucci, G. Designing a willing-to-use-in-public hand gestural interaction technique for smart glasses. In Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, San Jose, CA, USA, 7–12 May 2016; pp. 4203–4215. [Google Scholar]

- Lucero, A.; Vetek, A. NotifEye: Using interactive glasses to deal with notifications while walking in public. In Proceedings of the 11th Conference on Advances in Computer Entertainment Technology, Funchal, Portugal, 11–14 November 2014; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Bargh, J.A. Social Psychology and the Unconscious: The Automaticity of Higher Mental Processes; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Banaji, M.R.; Bhaskar, R.; Brownstein, M. When bias is implicit, how might we think about repairing harm? Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2015, 6, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E.T. Knowledge activation: Accessibility, applicability, and salience. In Social Psychology: Handbook of Basic Principles; Higgins, E.T., Kruglanski, A., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996; pp. 133–168. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald, A.G.; McGhee, D.E.; Schwartz, J.L. Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: The implicit association test. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 74, 1464–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiske, S.T. Stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination at the seam between the centuries: Evolution, culture, mind, and brain. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 30, 299–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banaji, M.R.; Hardin, C.D. Automatic stereotyping. Psychol. Sci. 1996, 7, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiske, S.; Cuddy, A.; Glick, P. Universal dimensions of social cognition: Warmth and competence. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2007, 11, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abele, A.E.; Ellemers, N.; Fiske, S.T.; Koch, A.; Yzerbyt, V. Navigating the social world: Toward an integrated framework for evaluating self, individuals, and groups. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 128, 290–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, M.H.; Kwan, V.S.; Cheung, A.; Fiske, S.T. Stereotype content model explains prejudice for an envied outgroup: Scale of anti-Asian American stereotypes. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2005, 31, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuddy, A.J.; Fiske, S.T. Doddering but dear: Process, content, and function in stereotyping of older persons. Ageism Stereotyping Prejud. Against Older Pers. 2002, 3, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Eckes, T. Paternalistic and Envious Gender Stereotypes: Testing Predictions from the Stereotype Content Model. Sex Roles 2002, 47, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glick, P.; Diebold, J.; Bailey-Werner, B.; Zhu, L. The Two Faces of Adam: Ambivalent Sexism and Polarized Attitudes Toward Women. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1997, 23, 1323–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, W.; Eagly, A.H. Biosocial construction of sex differences and similarities in behavior. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 46, 55–123. [Google Scholar]

- Ellemers, N. Gender stereotypes. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2018, 69, 275–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eagly, A.H.; Wood, W. Social role theory. In Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Cuddy, A.; Fiske, S.; Kwan, V.; Glick, P.; Demoulin, S.; Leyens, J.P.; Bond, M.H.; Croizet, J.C.; Ellemers, N.; Sleebos, E. Stereotype content model across cultures: Towards universal similarities and some differences. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 48, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscatelli, S.; Menegatti, M.; Ellemers, N.; Mariani, M.G.; Rubini, M. Men should be competent, women should have it all: Multiple criteria in the evaluation of female job candidates. Sex Roles 2020, 83, 269–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines, E.L.; Deaux, K.; Lofaro, N. The times they are a-changing… or are they not? A comparison of gender stereotypes, 1983–2014. Psychol. Women Q. 2016, 40, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Diekman, A.B.; Eagly, A.H. Stereotypes as dynamic constructs: Women and men of the past, present, and future. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2000, 26, 1171–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson Sendén, M.; Klysing, A.; Lindqvist, A.; Renström, E.A. The (not so) changing man: Dynamic gender stereotypes in Sweden. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eagly, A.H.; Nater, C.; Miller, D.I.; Kaufmann, M.; Sczesny, S. Gender stereotypes have changed: A cross-temporal meta-analysis of US public opinion polls from 1946 to 2018. Am. Psychol. 2020, 75, 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Athenstaedt, U.; Heinzle, C.; Lerchbaumer, G. Gender subgroup self-categorization and gender role self-concept. Sex Roles 2008, 58, 266–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckes, T. Features of men, features of women: Assessing stereotypic beliefs about gender subtypes. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 33, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, M.L.; Brewer, M.B. The structure of female subgroups: An exploration of ambivalent stereotypes. Sex Roles 2006, 54, 753–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friehs, M.T.; Aparicio Lukassowitz, F.; Wagner, U. Stereotype content of occupational groups in Germany. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2022, 52, 459–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiske, S.T.; Durante, F. Never trust a politician? Collective distrust, relational accountability, and voter response. In Power, Politics, and Paranoia: Why People Are Suspicious of Their Leaders; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014; pp. 91–105. [Google Scholar]

- Fiske, S.T.; Dupree, C. Gaining trust as well as respect in communicating to motivated audiences about science topics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 13593–13597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Strinić, A.; Carlsson, M.; Agerström, J. Occupational stereotypes: Professionals warmth and competence perceptions of occupations. Pers. Rev. 2021, 51, 603–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.C.; Kang, S.K.; Tse, K.; Toh, S.M. Stereotypes at work: Occupational stereotypes predict race and gender segregation in the workforce. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 115, 103318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irmen, L.; Linner, U. Die Repräsentation generisch maskuliner Personenbezeichnungen. J. Psychol. 2005, 213, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purdie-Vaughns, V.; Eibach, R.P. Intersectional invisibility: The distinctive advantages and disadvantages of multiple subordinate-group identities. Sex Roles 2008, 59, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glick, P. Trait-based and sex-based discrimination in occupational prestige, occupational salary, and hiring. Sex Roles 1991, 25, 351–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glick, P.; Wilk, K.; Perreault, M. Images of occupations: Components of gender and status in occupational stereotypes. Sex Roles 1995, 32, 565–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.J.; White, G.B. Implicit and explicit occupational gender stereotypes. Sex Roles 2006, 55, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghavami, N.; Peplau, L.A. An intersectional analysis of gender and ethnic stereotypes: Testing three hypotheses. Psychol. Women Q. 2013, 37, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.K.; Bodenhausen, G.V. Multiple identities in social perception and interaction: Challenges and opportunities. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2015, 66, 547–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klysing, A.; Lindqvist, A.; Björklund, F. Stereotype content at the intersection of gender and sexual orientation. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 713839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudman, L.A. Self-promotion as a risk factor for women: The costs and benefits of counterstereotypical impression management. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 74, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivens, B.S.; Leischnig, A.; Muller, B.; Valta, K. On the role of brand stereotypes in shaping consumer response toward brands: An empirical examination of direct and mediating effects of warmth and competence. Psychol. Mark. 2015, 32, 808–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kervyn, N.; Fiske, S.T.; Malone, C. Brands as intentional agents framework: How perceived intentions and ability can map brand perception. J. Consum. Psychol. 2012, 22, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chattalas, M.; Kramer, T.; Takada, H. The impact of national stereotypes on the country of origin effect: A conceptual framework. Int. Mark. Rev. 2008, 25, 54–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Antonetti, P.; Maklan, S. Hippies, greenies, and tree huggers: How the “warmth” stereotype hinders the adoption of responsible brands. Psychol. Mark. 2016, 33, 796–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hohenberger, C.; Spörrle, M.; Welpe, I.M. How and why do men and women differ in their willingness to use automated cars? The influence of emotions across different age groups. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2016, 94, 374–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersson, I.; Karlsson, I.M. Setting the stage for autonomous cars: A pilot study of future autonomous driving experiences. IET Intell. Transp. Syst. 2015, 9, 694–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.A.; Hopkins, D. Autonomous vehicles and the future of urban tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 74, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taeihagh, A.; Lim, H.S.M. Governing autonomous vehicles: Emerging responses for safety, liability, privacy, cybersecurity, and industry risks. Transp. Rev. 2019, 39, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hevelke, A.; Nida-Rümelin, J. Responsibility for crashes of autonomous vehicles: An ethical analysis. Sci. Eng. Ethics 2015, 21, 619–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Awad, E.; Levine, S.; Kleiman-Weiner, M.; Dsouza, S.; Tenenbaum, J.B.; Shariff, A.; Bonnefon, J.-F.; Rahwan, I. Blaming humans in autonomous vehicle accidents: Shared responsibility across levels of automation. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1803.07170. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.; Seppelt, B.; Reimer, B.; Mehler, B.; Coughlin, J.F. Acceptance of vehicle automation: Effects of demographic traits, technology experience and media exposure. Proc. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. Annu. Meet. 2019, 63, 2066–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotopoulos, I.; Dimitrakopoulos, G. An empirical investigation on consumers’ intentions towards autonomous driving. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2018, 95, 773–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegner, S.M.; Beldad, A.D.; Brunswick, G.J. In automatic we trust: Investigating the impact of trust, control, personality characteristics, and extrinsic and intrinsic motivations on the acceptance of autonomous vehicles. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2019, 35, 1769–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; Lim, J.; Cho, Y. Understanding the emergence and social acceptance of electric vehicles as next-generation models for the automobile industry. Sustainability 2018, 10, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pani, A.; Mishra, S.; Golias, M.; Figliozzi, M. Evaluating public acceptance of autonomous delivery robots during COVID-19 pandemic. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2020, 89, 102600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapser, S. User Acceptance of Autonomous Delivery Vehicles—An Empirical Study in Germany. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Northumbria at Newcastle, Newcastle, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, K.; Wien, J.; Molin, E.; Cats, O.; Morsink, P.; Van Arem, B. Taking the self-driving bus: A passenger choice experiment. In Proceedings of the 2019 6th International Conference on Models and Technologies for Intelligent Transportation Systems (MT-ITS), Cracow, Poland, 5–7 June 2019; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Hellinger, M.; Motschenbacher, H. Gender Across Languages: Volume 4; John Benjamins Publishing Company: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Asbrock, F. Die Systematik Diskriminierenden Verhaltens Gegenüber Unterschiedlichen Gesellschaftlichen Gruppen. 2008. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/15979193.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2023).

- Asbrock, F. Stereotypes of social groups in Germany in terms of warmth and competence. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 41, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duden. Cornelsen Verlag GmbH. 2022. Available online: https://www.duden.de/rechtschreibung/gutmuetig (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Rudman, L.A.; Glick, P. Prescriptive Gender Stereotypes and Backlash Toward Agentic Women. J. Soc. Issues 2001, 57, 743–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudman, L.A.; Fairchild, K. Reactions to counterstereotypic behavior: The role of backlash in cultural stereotype maintenance. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 87, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pröbster, M.; Marsden, N. Real Gender Barriers to Virtual Realities? In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Engineering, Technology and Innovation (ICE/ITMC), Cardiff, UK, 21–23 June 2021; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Nisbett, R.E.; Wilson, T.D. The halo effect: Evidence for unconscious alteration of judgments. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1977, 35, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldoory, L.; Jiang, H.; Toth, E.L.; Sha, B.-L. Is it still just a women’s issue? A study of work-life balance among men and women in public relations. Public Relat. J. 2008, 2, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neil, J.M. Summarizing 25 years of research on men’s gender role conflict using the Gender Role Conflict Scale: New research paradigms and clinical implications. Couns. Psychol. 2008, 36, 358–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, T. How Important Are Ethical Dilemmas to Potential Adopters of Autonomous Vehicles? Ethics Inf. Technol. 2021, 23, 657–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Payre, W.; Cestac, J.; Delhomme, P. Intention to use a fully automated car: Attitudes and a priori acceptability. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2014, 27, 252–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Groups | Competence | Warmth |

|---|---|---|

| Men using ADV | 3.67 (0.78) | 3.24 (0.75) |

| Men | 3.65 (0.74) | 3.22 (0.73) |

| Women using ADV | 3.79 (0.80) | 3.52 (0.77) |

| Women | 3.68 (0.74) | 3.89 (0.61) |

| Male physicians using ADV | 3.91 (0.80) | 3.35 (0.74) |

| Male physicians | 3.78 (0.75) | 3.32 (0.61) |

| Female physicians using ADV | 3.90 (0.81) | 3.44 (0.76) |

| Female physicians | 3.93 (0.77) | 3.53 (0.71) |

| Female homemakers using ADV | 3.60 (0.84) | 3.46 (0.78) |

| Female homemakers | 3.36 (0.79) | 3.73 (0.79) |

| Male homemakers using ADV | 3.50 (0.83) | 3.31 (0.71) |

| Male homemakers | 3.41 (0.80) | 3.72 (0.72) |

| Male college students using ADV | 3.79 (0.84) | 3.46 (0.68) |

| Male college students | 3.64 (0.73) | 3.66 (0.71) |

| Female college students using ADV | 3.86 (0.78) | 3.64 (0.70) |

| Female college students using ADV | 3.83 (0.66) | 3.71 (0.80) |

| Business men using ADV | 3.97 (0.66) | 3.13 (0.67) |

| Business men | 3.88 (0.71) | 2.79 (0.72) |

| Business women using ADV | 4.01 (0.75) | 3.31 (0.79) |

| Business women | 3.89 (0.70) | 3.24 (0.63) |

| Unemployed women using ADV | 3.02 (0.90) | 3.22 (0.82) |

| Unemployed women | 2.85 (0.77) | 3.24 (0.74) |

| Unemployed men using ADV | 2.91 (0.86) | 2.92 (0.71) |

| Unemployed men | 2.56 (0.67) | 2.89 (0.58) |

| Men with handicaps using ADV | 3.43 (0.83) | 3.53 (0.73) |

| Men with handicaps | 3.16 (0.90) | 3.58 (0.78) |

| Women with handicaps using ADV | 3.44 (0.79) | 3.62 (0.63) |

| Women with handicaps | 3.14 (0.80) | 3.71 (0.80) |

| Retired men using ADV | 3.36 (0.85) | 3.48 (0.73) |

| Retired men | 3.05 (0.68) | 3.54 (0.67) |

| Retired women using ADV | 3.37 (0.87) | 3.40 (0.75) |

| Retired women | 3.08 (0.84) | 3.62 (0.77) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pröbster, M.; Marsden, N. The Social Perception of Autonomous Delivery Vehicles Based on the Stereotype Content Model. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5194. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065194

Pröbster M, Marsden N. The Social Perception of Autonomous Delivery Vehicles Based on the Stereotype Content Model. Sustainability. 2023; 15(6):5194. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065194

Chicago/Turabian StylePröbster, Monika, and Nicola Marsden. 2023. "The Social Perception of Autonomous Delivery Vehicles Based on the Stereotype Content Model" Sustainability 15, no. 6: 5194. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065194

APA StylePröbster, M., & Marsden, N. (2023). The Social Perception of Autonomous Delivery Vehicles Based on the Stereotype Content Model. Sustainability, 15(6), 5194. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065194