A Systematic Review of Factors Influencing the Vitality of Public Open Spaces: A Novel Perspective Using Social–Ecological Model (SEM)

Abstract

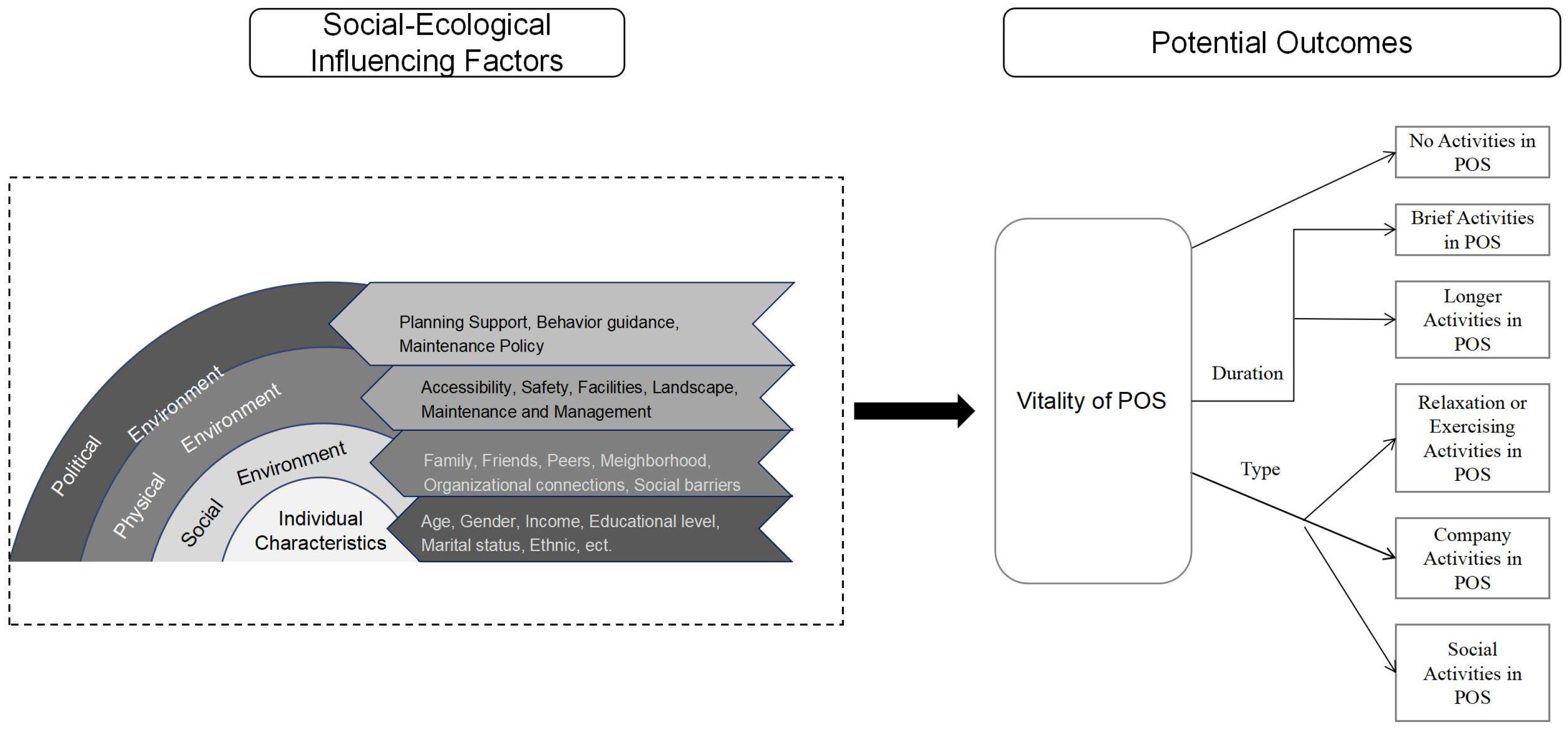

:1. Introduction

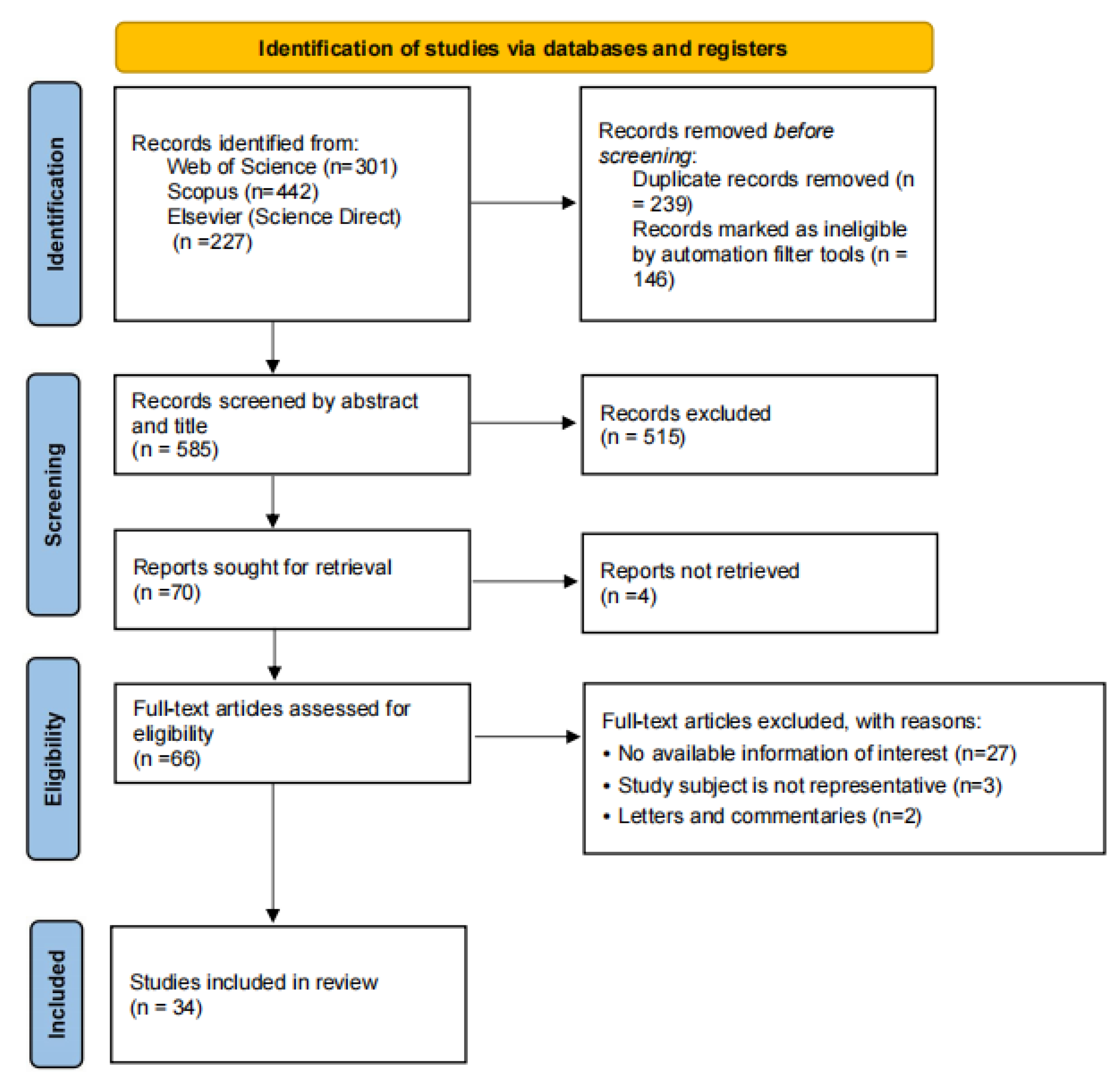

2. Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Individual Characteristics

3.2. Social Environment

3.3. Physical Environment

3.4. Political Environment

3.5. Limitation of This Literature Review

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

4.1. Neglect the Impact of Policy

4.2. Physical Environment Improvement as a Panacea

4.3. Future Development of SEM

4.4. Strategies to Enhance Vitality of POS

4.5. Identified Gaps in the Literature

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. THE 17 GOALS | Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Carr, S.; Francis, M.; Rivlin, L.G.; Stone, A.M. Public Space; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, H. Linking the quality of public spaces to quality of life. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2009, 2, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitrakar, R.; Baker, D.; Guaralda, M. Emerging challenges in the management of contemporary public spaces in urban neighbourhoods. Archnet-Ijar 2017, 11, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ismail, W.A.W.; Said, I. Integrating the community in urban design and planning of public spaces: A review in Malaysian cities. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 168, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ling, G.H.T.; Leng, P.C. Ten steps qualitative modelling: Development and validation of conceptual Institutional-social-ecological model of public open space (POS) governance and quality. Resources 2018, 7, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carmona, M. Principles for public space design, planning to do better. Urban Des. Int. 2019, 24, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khaza, M.K.B.; Rahman, M.M.; Harun, F.; Roy, T.K. Accessibility and service quality of public parks in Khulna city. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2020, 146, 04020024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micek, M.; Staszewska, S. Urban and rural public spaces: Development issues and qualitative assessment. Bull. Geogr. Socio-Econ. Ser. 2019, 45, 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Palacky, J.; Wittmann, M.; Frantisak, L. Evaluation of urban open spaces sustainability. In Proceedings of the 29th Annual AESOP 2015 Congress, Prague, Czech Republic, 13–16 June 2015; pp. 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- Colwill, S. Use and Abuse: Reading the Patina of User Actions in Public Space; Technische Universität Berlin: Berlin, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hai, W.; Difei, J. Evaluation system research on vitality of urban public space. J. Railw. Sci. Eng. 2012, 9, 56–60. [Google Scholar]

- Gumano, H.N.; Eriawan, T.; Nur, H. Kajian Tingkat Efektifitas Ruang Publik yang Tersedia Pada Pusat Kota-Kota di Provinsi Sumatera Barat Berdasarkan Metode “Good Public Space Index (GPSI)”; Abstract of Undergraduate Research; Faculty of Civil and Planning Engineering, Bung Hatta University: Sumatera Barat, Indonesia, 2016; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Siregar, J.P. Assessment of public space quality using good public space index (case study of Merjosari sub district, Municipality of Malang, Indonesia). Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 135, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, W.; Lawson, G. Meeting and greeting: Activities in public outdoor spaces outside high-density urban residential communities. Urban Des. Int. 2009, 14, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gehl, J. Life between Buildings; Van Nostrand Reinhold: New York, NY, USA, 1987; Volume 23. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, K. Reconsidering the image of the city. In Cities of the Mind; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1984; pp. 151–161. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, J. Making a city: Urbanity, vitality and urban design. J. Urban Des. 1998, 3, 93–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities: The Failure of Town Planning; Penguin Random House: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Available online: https://www.randomhousebooks.com/books/86058/ (accessed on 13 February 2023).

- Xiangyu, Z. Construction of Vitality of Public Space in New Urban Area: A Case Study of Honggutan New District of Nanchang City. Asian Agric. Res. 2020, 12, 30–33. [Google Scholar]

- Difei, J. The Theory of City Form Vitality; Nanjing Southeast University Publishing House: Nanjing, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jalaladdini, S.; Oktay, D. Urban public spaces and vitality: A socio-spatial analysis in the streets of Cypriot towns. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 35, 664–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Niu, T.; Qing, L.; Han, L.; Long, Y.; Hou, J.; Li, L.; Tang, W.; Teng, Q. Small public space vitality analysis and evaluation based on human trajectory modeling using video data. Build. Environ. 2022, 225, 109563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalili, A.; Fallah, S.N. Role of social indicators on vitality parameter to enhance the quality of women’s communal life within an urban public space (case: Isfahan’ s traditional bazaar, Iran). Front. Archit. Res. 2018, 7, 440–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Miao, W.; Si, H.; Liu, T. Urban Vitality Evaluation and Spatial Correlation Research: A Case Study from Shanghai, China. Land 2021, 10, 1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, S.L.; Sallis, J.F.; Ritenbaugh, C.; Hill, J.O.; Birch, L.L.; Frank, L.D.; Glanz, K.; Himmelgreen, D.A.; Mudd, M.; Popkin, B.M.; et al. Environmental and societal factors affect food choice and physical activity: Rationale, influences, and leverage points. Nutr. Rev. 2001, 59, S21–S36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cohen, D.A.; Scribner, R.A.; Farley, T.A. A structural model of health behavior: A pragmatic approach to explain and influence health behaviors at the population level. Prev. Med. 2000, 30, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Ecological models of human development. Int. Encycl. Educ. 1994, 3, 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Saelens, B.E.; Sallis, J.F.; Frank, L.D. Environmental correlates of walking and cycling: Findings from the transportation, urban design, and planning literatures. Ann. Behav. Med. 2003, 25, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallis, J.F.; Owen, N. Physical Activity and Behavioral Medicine; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, T. Applying the socio-ecological model to improving fruit and vegetable intake among low-income African Americans. J. Community Health 2008, 33, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elder, J.P.; Lytle, L.; Sallis, J.F.; Young, D.R.; Steckler, A.; Simons-Morton, D.; Stone, E.; Jobe, J.B.; Stevens, J.; Lohman, T.; et al. A description of the social–ecological framework used in the trial of activity for adolescent girls (TAAG). Health Educ. Res. 2007, 22, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spence, J.C.; Lee, R.E. Toward a comprehensive model of physical activity. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2003, 4, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, O.R.; Berkhout, F.; Gallopin, G.C.; Janssen, M.A.; Ostrom, E.; Van der Leeuw, S. The globalization of socio-ecological systems: An agenda for scientific research. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2006, 16, 304–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrosillo, I.; Zurlini, G.; Grato, E.; Zaccarelli, N. Indicating fragility of socio-ecological tourism-based systems. Ecol. Indic. 2006, 6, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallis, H.M.; Kareiva, P. Shaping global environmental decisions using socio-ecological models. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2006, 21, 562–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehrani, H.; Majlessi, F.; Shojaeizadeh, D.; Sadeghi, R.; Kabootarkhani, M.H. Applying socioecological model to improve women’s physical activity: A randomized control trial. Iran. Red Crescent Med. J. 2016, 18, e21072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, e1–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tan, P.Y.; Ismail, H.N.; Syed Jaafar, S.M.R. A comparative review: Distance decay in urban and rural tourism. Anatolia 2022, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Ling, G.H.T. A Systematic Review of Morphological Transformation of Urban Open Spaces: Drivers, Trends, and Methods. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kmet, L.M.; Cook, L.S.; Lee, R.C. Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers from a Variety of Fields; Education and Research Archive: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Z.; Duan, J.; Lu, Y.; Zou, W.; Lan, W. A geographical detector study on factors influencing urban park use in Nanjing, China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 59, 126996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siderelis, C.; Moore, R.L.; Leung, Y.F.; Smith, J.W. A nationwide production analysis of state park attendance in the United States. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 99, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aliyas, Z. A qualitative study of park-based physical activity among adults. J. Public Health 2020, 28, 623–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Chen, Y. Analysis of Factors Influencing Street Vitality in High-Density Residential Areas Based on Multi-source Data: A Case Study of Shanghai. Int. J. High-Rise Build. 2021, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, B.; Sun, W.; Wu, J. Analysis of Spatiotemporal Characteristics and Recreational Attraction for POS in Urban Communities: A Case Study of Shanghai. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, E.; Timperio, A.; Loh, V.H.; Deforche, B.; Veitch, J. Critical factors influencing adolescents’ active and social park use: A qualitative study using walk-along interviews. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 58, 126948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, C.; Hernández, A.; Hermosillo-Gallardo, M.E.; Gómez Gámez, C.I.; Resendiz, E.; Morales, M.; Nieto, C.; Moreno, M.; Barquera, S. Development and Validation of the Mexican Public Open Spaces Tool (MexPOS). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fongar, C.; Aamodt, G.; Randrup, T.B.; Solfjeld, I. Does perceived green space quality matter? Linking Norwegian adult perspectives on perceived quality to motivation and frequency of visits. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, S.; Yung, E.H.K.; Sun, Y. Effects of open space accessibility and quality on older adults’ visit: Planning towards equal right to the city. Cities 2022, 125, 103611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, C.; Song, Y.; He, Q.; Shen, F. Spatially explicit assessment on urban vitality: Case studies in Chicago and Wuhan. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 40, 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Shen, G.Q. Encouraging the use of urban green space: The mediating role of attitude, perceived usefulness and perceived behavioural control. Habitat Int. 2015, 50, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Lu, S. Evaluation of the use of Urban Public Space Based on PSPL—Taking the Place as an Example. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Engineering Simulation and Intelligent Control (ESAIC), Hunan, China, 10–11 August 2018; pp. 44–48. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Y.; Qiu, H. Exploring affecting factors of park use based on multisource big data: Case study in Wuhan, China. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2021, 147, 05020037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Hu, J.; Liu, K.; Xue, J.; Ning, L.; Fan, J. Exploring Park Visit Variability Using Cell Phone Data in Shenzhen, China. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addas, A. Exploring the pattern of use and accessibility of urban green spaces: Evidence from a coastal desert megacity in Saudi Arabia. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 55757–55774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaymaz, I.; Oguz, D.; Cengiz-Hergul, O.C. Factors influencing children’s use of urban green spaces. Indoor Built Environ. 2019, 28, 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schipperijn, J.; Ekholm, O.; Stigsdotter, U.K.; Toftager, M.; Bentsen, P.; Kamper-Jørgensen, F.; Randrup, T.B. Factors influencing the use of green space: Results from a Danish national representative survey. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 95, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hecke, L.; Verhoeven, H.; Clarys, P.; Van Dyck, D.; Van de Weghe, N.; Baert, T.; Deforche, B.; Van Cauwenberg, J. Factors related with public open space use among adolescents: A study using GPS and accelerometers. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2018, 17, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Lu, T.; Yishake, G. How to promote residents’ use of green space: An empirically grounded agent-based modeling approach. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 67, 127435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrows, E.; O’Mahony, M.; Geraghty, D. How urban parks offer opportunities for physical activity in Dublin, Ireland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, B.; Sun, Z.; Bao, Z. Landscape perception and recreation needs in urban green space in Fuyang, Hangzhou, China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2013, 12, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, D.G.; Teixeira, C.P.; Fernandes, C.O.; Olszewska-Guizzo, A.; Dias, R.C.; Vilaça, H.; Barros, N.; Maia, R.L. Patterns of human behaviour in public urban green spaces: On the influence of users’ profiles, surrounding environment, and space design. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 74, 127668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misiune, I.; Julian, J.P.; Veteikis, D. Pull and push factors for use of urban green spaces and priorities for their ecosystem services: Case study of Vilnius, Lithuania. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 58, 126899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhou, W. Recreational visits to urban parks and factors affecting park visits: Evidence from geotagged social media data. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 180, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanesi, G.; Chiarello, F. Residents and urban green spaces: The case of Bari. Urban For. Urban Green. 2006, 4, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, B.; Liu, C.; Mu, T.; Xu, X.; Tian, G.; Zhang, Y.; Kim, G. Spatiotemporal fluctuations in urban park spatial vitality determined by on-site observation and behavior mapping: A case study of three parks in Zhengzhou City, China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 64, 127246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zhou, B.; Han, L.; Mei, R. The motivation and factors influencing visits to small urban parks in Shanghai, China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 60, 127086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiplagat, A.K.; Koech, J.K.; Ng’etich, J.K.; Lagat, M.J.; Khazenzi, J.A.; Odhiambo, K.O. Urban green space characteristics, visitation patterns and influence of visitors’ socio-economic attributes on visitation in Kisumu City and Eldoret Municipality, Kenya. Trees For. People 2022, 7, 100175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, N.A.A.; Mokhtar, M.D.M.; Raman, T.L.; Saikim, F.H.; Nordin, N.M. Use of Urban Green Spaces: A Case Study In Taman Merdeka, Johor Bahru. Alam Cipta 2020, 13, 54–60. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, C.; Fu, L.; Xue, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y. Using multi-source data to understand the factors affecting mini-park visitation in Yancheng. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2022, 49, 754–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratiwi, W.D.; Nagari, B.K.; Margono, R.B.; Suryani, S. Visitor’s Intentions To Re-Visit Reconstructed Public Place In Jakarta Tourism Heritage Riverfront. Alam Cipta 2022, 15, 2–9. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.; Lu, H.; Zheng, T.; Rong, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, W.; Yan, Y.; Tang, L. Vitality of urban parks and its influencing factors from the perspective of recreational service supply, demand, and spatial links. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, T.; Xie, X.; Marušić, B.G. What attracts people to visit community open spaces? A case study of the Overseas Chinese Town community in Shenzhen, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liu, S.; Lai, S.Q.; Liu, C.; Jiang, L. What influenced the vitality of the waterfront open space? A case study of Huangpu River in Shanghai, China. Cities 2021, 114, 103197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinner, M.B. Social ecological perspective on intercultural communication. In The International Encyclopedia of Intercultural Communication; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Hinner, M.B. Can the Social Ecological Model Help Overcome Prejudices? In Cultural Conceptualizations in Language and Communication; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 239–256. [Google Scholar]

- Humbert, M.L.; Chad, K.E.; Spink, K.S.; Muhajarine, N.; Anderson, K.D.; Bruner, M.W.; Girolami, T.M.; Odnokon, P.; Gryba, C.R. Factors that influence physical activity participation among high-and low-SES youth. Qual. Health Res. 2006, 16, 467–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, D.; Sallis, J.F.; Conway, T.L.; Saelens, B.E.; Frank, L.D.; Cain, K.L.; Slymen, D.J. Interactive effects of built environment and psychosocial attributes on physical activity: A test of ecological models. Ann. Behav. Med. 2012, 44, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.Y.; Cameron, C.; DesMeules, M.; Morrison, H.; Craig, C.L.; Jiang, X. Individual, social, environmental, and physical environmental correlates with physical activity among Canadians: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2009, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maslow, A. Motivation and Personality; Harper & Rows: New York, NY, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Langille, J.L.D.; Rodgers, W.M. Exploring the influence of a social ecological model on school-based physical activity. Health Educ. Behav. 2010, 37, 879–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z. The Change and Reconstruction of Rural Public Space in the Process of Urbanization. Urban Stud. 2021, 28, 58–64. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid, T.L.; Pratt, M.; Witmer, L. A framework for physical activity policy research. J. Phys. Act. Health 2006, 3, S20–S29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, L. Rural Public Space Evolution and Reconstruction of Western Sichuan. Ph.D. Thesis, Southwest Jiaotong University, Chengdu, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, G.H.T.; Leng, P.C.; Ho, C.S. Effects of diverse property rights on rural neighbourhood public open space (POS) governance: Evidence from Sabah, Malaysia. Economies 2019, 7, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Clark, D. Number of Employees Worldwide from 1991 to 2022. Technical Report, 2022. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1258668/global-employment-figures-by-gender/ (accessed on 13 February 2023).

- Yang, G.; Hesheng, F. Reflection and reconstruction: The construction of rural public space from the perspective of Rural Revitalization. J. Inn. Mong. Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2019, 21, 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Swearer, S.M.; Hymel, S. Understanding the psychology of bullying: Moving toward a social-ecological diathesis–stress model. Am. Psychol. 2015, 70, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Golden, S.D.; Earp, J.A.L. Social ecological approaches to individuals and their contexts: Twenty years of health education & behavior health promotion interventions. Health Educ. Behav. 2012, 39, 364–372. [Google Scholar]

- Alfonzo, M.A. To walk or not to walk? The hierarchy of walking needs. Environ. Behav. 2005, 37, 808–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NAZARI, Z. The Study of Barriers to the Satisfactory Condition of Urban Improvement for the Disabled in Ahvaz City. Geogr. Hum. Relatsh. 2019, 2, 168–180. [Google Scholar]

| Articles Inclusion Criteria: |

|---|

| Studies of English writing |

| Publish time: 2000–2022 |

| Scholarly papers |

| The studies had to present original peer-reviewed research providing quantitative information about the relationship between the vitality of public open spaces and users’ individual, the physical environment, and social environment and policy factors. |

| Exclusion criteria: |

| Papers that are duplicated within the search documents |

| Papers that are not accessible, review papers |

| Papers that are not primary/original research |

| Study (Authors and Year) | Context | Sample Size and Data Collection | Influencing Factors | Results of POS Use | SEM Perspective |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fan et al., 2021 [42] | Urban | 178 POS Baidu heat map data Geographical detector | Park size, landscape shape index, park facilities, water size, vegetation coverage, road density, traffic convenience, distance from the urban center, park-surrounding facilities | Facilities around are the most significant drivers of park use, and there is a bi-variate enhancement or non-linear enhancement of the interaction effect manifested between each pair of drivers. | Physical Environment Social Environment |

| Siderelis et al., 2012 [43] | Urban, Periphery, Rural | 1350 POS Annual Information Exchange (AIX) | Numbers of workers, facilities of park-lands, capital investments. | Increased labor to maintain parkland increases park attendance, but more capital is noted, and the number of facilities does not increase park utilization. | Physical Environment Political Environment |

| Aliyas, 2020 [44] | Urban | 40 People Semi-Structured Interviews. | Characteristics of parks (e.g., size, facilities, accessibility, natural landscape, and safety)/Social factors (e.g., bad behavior and social support)/Individual factors (e.g., time, weather, negative attitudes, and health condition). | Physical characteristics of parks, social factors, and personal factors influence the selection of parks for physical activity. In addition, the combination of these factors influences the selection of physical activity parks for all age groups. | Individual Characteristics Social Environment Physical Environment |

| Yuan et al., 2021 [45] | Urban | 441 POS Field surveys | Transportation, built environment, population, the density of residential entrances and exits, walkable areas, and density of retail and service facilities. | The vitality of a street is related to the density of the population in the environment, the density of the residential entrances and exits, the proportion of walkable areas, and the density of retail and service facilities. | Physical Environment. |

| Yu et al., 2022 [46] | Urban | 1200 People GPS Path Tracking Geographical detector | Percentage of POS area, accessibility, population, percentage of commercial land, an area occupied per capita, percentage of residential land, and transportation convenience. | The percentage of public open-space area, accessibility, population density, percentage of commercial land use, and per capita occupancy influence the intensity of public open space use. | Physical Environment |

| Rivera et al., 2021 [47] | N/A | 34 People Interviews | Park’s natural features, sports facilities, aesthetics, location, green spaces, barbecue areas, seating, organized activities, shelters, safety, and social factors. | The park’s natural features, sports facilities, aesthetics, safety, social factors, and location will promote park visitation. Sports facilities and green spaces will promote physical activities. Furthermore, barbecue areas, sports features, seating, organized activities, and shelters will encourage socialization. | Physical Environment Social Environment |

| Medina et al., 2022 [48] | Urban | 944 POS Field surveys | Food and wellness environment, maintenance, amenities, legibility, security, perceived environment, and urban environment. | Food and wellness environment, maintenance, amenities, legibility, security, and environment will impact participants’ attendance in public open spaces. | Physical Environment Political Environment |

| Fongar et al., 2019 [49] | Urban Suburban Rural | 1010 People Questionnaire | Age, gender, the degree of urbanization, households with children under 18 years of age, perceived quality, distance, education, and noise. | Norwegians perceive their green spaces to be of good quality, and the perception of higher quality has a positive impact on green space visitation. | Individual Characteristics Physical Environment |

| Wang et al., 2022 [50] | Urban | 238 POS Map data | Accessibility, surrounding facilities, integration, number, area, public transport, facility type and quality, landscape, maintenance, and quietness. | The quality of open space has a more significant impact on the number of elderly visitors than accessibility factors. | Physical Environment Political Environment |

| Chen et al., 2018 [51] | Urban | 686 POS GPS data | Accessibility, surrounding facilities, POS integration, POS number and area, public transport, facilities, landscape, maintenance, and quietness. | The quality of an open space has a more significant impact on the number of elderly visitors than accessibility factors. | Physical Environment Political Environment |

| Wan et al., 2015 [52] | Urban | 263 People Questionnaire | Facilities, perceived naturalness, accessibility, attitude, usefulness, subjective norm, behavioral control, behavioral intention, behavior. | Perceived provision of facilities, accessibility, attitude, subjective norms, PBC, behavioral intention, and usefulness relate positively to the behavioral intention to use urban green spaces. | Physical Environment Individual Characteristics |

| Jiang et al., 2018 [53] | Urban | 91 People Questionnaire | Age, time, walking system, rest space, square landscape and facilities design, seasons, social interaction, media art. | Comfort, diversity, public activities, and social interaction will enhance the vitality of public spaces. | Individual Characteristics Physical Environment Social Environment |

| Ye & Qiu, 2021 [54] | Urban | 70 POS Social-media data Message Board | Park age, square, facilities, water, accessibility, park attributes, distance to the city center, accessible area for a 10 min trip, surrounding point of interest, and population. | Large areas, adequate facilities, reasonable layout, accessibility, recreational facilities, services near points of interest, and prosperous organization of activities contribute to the improvement of park utilization. | Physical Environment Social Environment |

| He et al., 2022 [55] | Urban | 56 POS Gaode Maps Google Images | Age, gender, park attributes, park vegetation, surrounding, and serviceability. | Gender, age and park aggregation influence users’ participation in parks. | Individual Characteristics Physical Environment |

| Addas, 2022 [56] | Urban | 409 People Questionnaire | Gender, nationality, educational level, occupation, socio-demographic attributes, seasonal variation, the pattern of use, accessibility, benefits or purpose of park use, park attributes, and policy. | Urban parks are mainly used for spending time with others, followed by mental relaxation, sports activities, and children’s company. Seasonal changes, socio-demographic attributes, and urban management largely affect the park’s use. | Individual Characteristics Physical Environment Political Environment |

| Kaymaz et al., 2019 [57] | Urban | 1299 People Questionnaire | Age, gender, property type, outdoor activity preferences, neighborhood’s built environment, accessibility, safety, space design, temperature, density vegetation, shady areas, facilities, duration of living in the neighborhood. | The benefits of outdoor activities, safety concerns, and design features are the three main factors that influence the use of green space by parents and children. Social, cultural, and physical environments are all influences on children’s green space use. | Individual Characteristics Social Environment Physical Environment |

| Schipperijn et al., 2010 [58] | N/A | 11,238 People Questionnaire | Distance, accommodation type, size of the municipality, ethnic background, reasons for visiting green space. | Enjoying the weather and fresh air were the mainly reasons for respondents to visit green spaces. For most Danes, distance to green spaces is not a limiting factor for visiting green spaces. | Physical Environment Individual Characteristics |

| Van Hecke et al., 2018 [59] | Urban | 173 People Questionnaire GPS Interview | Education, ethnicity, location, gender, age, sports club membership | The purpose of visiting public open spaces was recreational, and participants spent more time when accompanied. Boys and less-educated adolescents were more likely to use public spaces. | Individual Characteristics |

| Liang et al., 2022 [60] | Urban | 402 People Questionnaire | Exercises, safety, accessibility, social interaction, consumption, public participation, environment, age, income, education, policy intensity, the effectiveness of a policy, and gender. | The primary needs of residents for green space are environmental connection, safety, and accessibility, and the needs vary by gender, education level, and income. | Individual Characteristics Social Environment Physical Environment Political Environment |

| Burrows et al., 2018 [61] | Urban | 865 People Questionnaire | Gender, age, visit the park alone or with others, proximity of residents to the park, quiet, visit reason. | When and why individuals go to the park, the distance from the park has a more significant impact on the visit frequency than age, gender, and impressions of park sound levels. | Individual Characteristics Social Environment |

| Zhang et al., 2013 [62] | Rural | 364 People Site survey Questionnaire | Gender, age, education, occupation, income, household size, residence, house size, dwelling location, vegetation, topography, garden ornaments, historicity, and recreation facility. Safety, naturalness, uniqueness. | Differences in age, gender, income, and education level determine the demand for green space recreation. Green space environment and accessibility are the two main factors that influence residents’ choices. | Individual Characteristics Physical Environment |

| Vidal et al., 2022 [63] | Urban | 979 People Observation | Age, physical activity level, status, mobility, weather, day period, temperature, size, deprivation cluster, socio-economic profile, space shape, vegetation, urban furniture, and surroundings. | The use of urban public green space is related to the situation of the users, the poverty level of the surrounding environment, and the design of the space. | Individual Characteristics Physical Environment |

| Misiune et al., 2021 [64] | Urban | 444 People Questionnaire | Ecosystem services, nature benefits, distance, recreational infrastructure, safety concerns, noise, vegetation allergies, accessibility, free time. | The most important factors that attract people to green spaces include distance and safety, leisurely walks, enjoyment of fresh air, observation of nature, relaxation, and recreation. | Individual Characteristics Physical Environment |

| Zhang et al., 2018 [65] | Urban | 127 POS Social-media data | Park size, entrance fee, presence of water, vegetation cover rate, number of bus stops, population density, average housing price, number of nearby parks, distance to urban center. | The number of bus stops is positively correlated with park visitation. Improving park accessibility through public transportation and planning small, accessible green spaces are effective in improving park use. | Physical Environment Social Environment |

| Sanesi et al., 2006 [66] | Urban | 351 People Questionnaire | Age, sex, function, size, maintenance and structures, facilities, safety, marital status, area of residence. | The use of public green space is closely related to age, gender, marital status, and area of residence. | Individual Characteristics |

| Mu et al., 2021 [67] | Urban | 150 People Field investigations Observations Questionnaire | Age, congregation spaces, locations, facilities, type of land use, accessibility, diversity of sub-spaces and activities, plants, landscape, water quality. | Park spatial vitality varies across time and space, and spatial vitality is influenced by park location, amenities, and visitors’ age group. | Individual Characteristics Physical Environment |

| Wang et al., 2021 [68] | Urban | 634 People Questionnaire | Age, reasons for SUGS use, socio-demographic factors, personal factors, spatial attributes of residence, park features factors, with a child under seven years of age, noise, facility, income, distance, and residential green spaces. | Relaxation and rest, physical exercise, and meeting friends were the most common reasons for using SUGS. Age, willingness to access nature, having children under seven years of age, noise, and facilities were positively associated with SUGS use. Income, distance from home to park, and residential green space were negative. | Individual Characteristics Physical Environment |

| Kiplagat et al., 2022 [69] | Urban | 1030 People Observations Questionnaire | Size, accessibility, maintenance, seats, security, vegetation, activities, facilities, parking lots, distance and cost to green spaces, socio-economic attributes of users (gender, age, marital status, occupation, household size, income, education level). | Green spaces that exhibited the most attributes were heavily visited. Gender, marital status, and educational attainment were significant socio-economic predictors of greens pace use. | Individual Characteristics Physical Environment |

| Aziz et al., 2020 [70] | Urban | 356 People Questionnaire | Age, ethnicity, gender, intention, self-efficacy, health condition, activities, features, routes, characters, distance, size, attractiveness, accessibility, comfort, and safety, family, peers, professionals, and community. | The majority of users of this park are Malays, with a higher number of people in the 26–32 age group. People within a 2 km radius visit this recreational area more often to rejuvenate and escape the busy city life. | Individual Characteristics Physical Environment |

| Zhou et al., 2022 [71] | Urban | 54 POS Geospatial data | Park area, distance to SBD, seats, recreational facilities, surroundings (toilets, retail shops, restaurants, bus stops, area of comprehensive parks, area of community parks, density of the traffic roads). | Socio-economic features of surroundings (population, housing price) Higher residential populations, more public restrooms, and larger open spaces are more likely to support small park access. However, the distance from downtown, surrounding large parks, and major roads do not support remote park access. | Physical Environment |

| Pratiwi1 et al., 2022 [72] | Urban | 105 People Observations Questionnaire | Age, gender, education, monthly revenue, accessibility, physical elements (pedestrian way, street furniture, visual along the corridor, social space). | Vision, ambiance, and spaciousness are considered to be the main attractions of heritage public spaces. | Individual Characteristics Physical Environment |

| Zhu et al., 2020 [73] | Urban | 90 POS Social-media data Gaode Map | Entrance fee, vegetation, water in the park, the density of facilities, distance to the urban center, population density, density of bus stops, diversity outside the park, and urban function density outside the park. | The vitality of urban parks decreases along an urban–rural gradient. Water in parks, the density of facilities, and nearby population density had a significant positive effect on park vitality. | Physical Environment |

| Chen et al., 2016 [74] | Urban | 112 POS Interview Environment scan Observation | Accessible lawn area, woodland area, footpath length, pavement, facilities, commercial facility sites, seats, shading devices, parking facilities, trash cans, landscape, and lighting. | Large accessible lawns, well-maintained sidewalks, seating, commercial facilities, and water features are essential features that can increase the use of open space in a community. | Physical Environment |

| Liu et al., 2021 [75] | Urban | 102 POS Baidu heat map data Geographical detector | Site design characteristics (shorelines open degree, public service facility density, non-motorized vehicle lane density) Traffic accessibility (bus station coverage index, road network density, non-motorized vehicle lane accessibility) Surroundings building and population. Service facility (surrounding commercial service density, catering facilities) | Site design, surrounding population, and services have a significant positive impact, while accessibility has a negative impact on vitality. | Physical Environment Social Environment |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, D.; Ling, G.H.T.; Misnan, S.H.b.; Fang, M. A Systematic Review of Factors Influencing the Vitality of Public Open Spaces: A Novel Perspective Using Social–Ecological Model (SEM). Sustainability 2023, 15, 5235. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065235

Zhang D, Ling GHT, Misnan SHb, Fang M. A Systematic Review of Factors Influencing the Vitality of Public Open Spaces: A Novel Perspective Using Social–Ecological Model (SEM). Sustainability. 2023; 15(6):5235. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065235

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Danning, Gabriel Hoh Teck Ling, Siti Hajar binti Misnan, and Minglu Fang. 2023. "A Systematic Review of Factors Influencing the Vitality of Public Open Spaces: A Novel Perspective Using Social–Ecological Model (SEM)" Sustainability 15, no. 6: 5235. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065235