2.1. Literature Review

COVID-19 has had enormous economic and social impacts. The impact of the pandemic on government finances has been widely analyzed [

6,

7], and this article is closely related to these studies. Because local governments are key actors in COVID-19 crisis management [

8], local budgets will suffer more due to COVID-19 than budgets at the central level [

9]. Local governments were found to adopt widely varied action strategies in response to COVID-19 [

10,

11], including containment and closure, economic response and health systems [

12], which significantly impact local government finances on both the expenditure and revenue sides of their budgets. On the one hand, the epidemic led to a decline in local fiscal revenue. Aiming at counteracting the effects of COVID-19, local governments were willing to exempt businesses from various fees and taxes [

11], and grant allowances, discounts and deferrals [

10]. Not only were tax revenues falling, but also parking fees, public transport fares, local accommodation fees, public hospital charges, fees for the use of public spaces and rental incomes [

9,

13]. On the other hand, the epidemic led to an increase in local fiscal expenditure. Local governments significantly increased public health expenditure for epidemic governance [

12]. At the same time, additional expenses for supporting residents and enterprises also increased sharply [

11]. The COVID-19 pandemic led to serious financial burdens for local governments due to falling incomes, rising expenditure and problems with budget stabilization [

14].

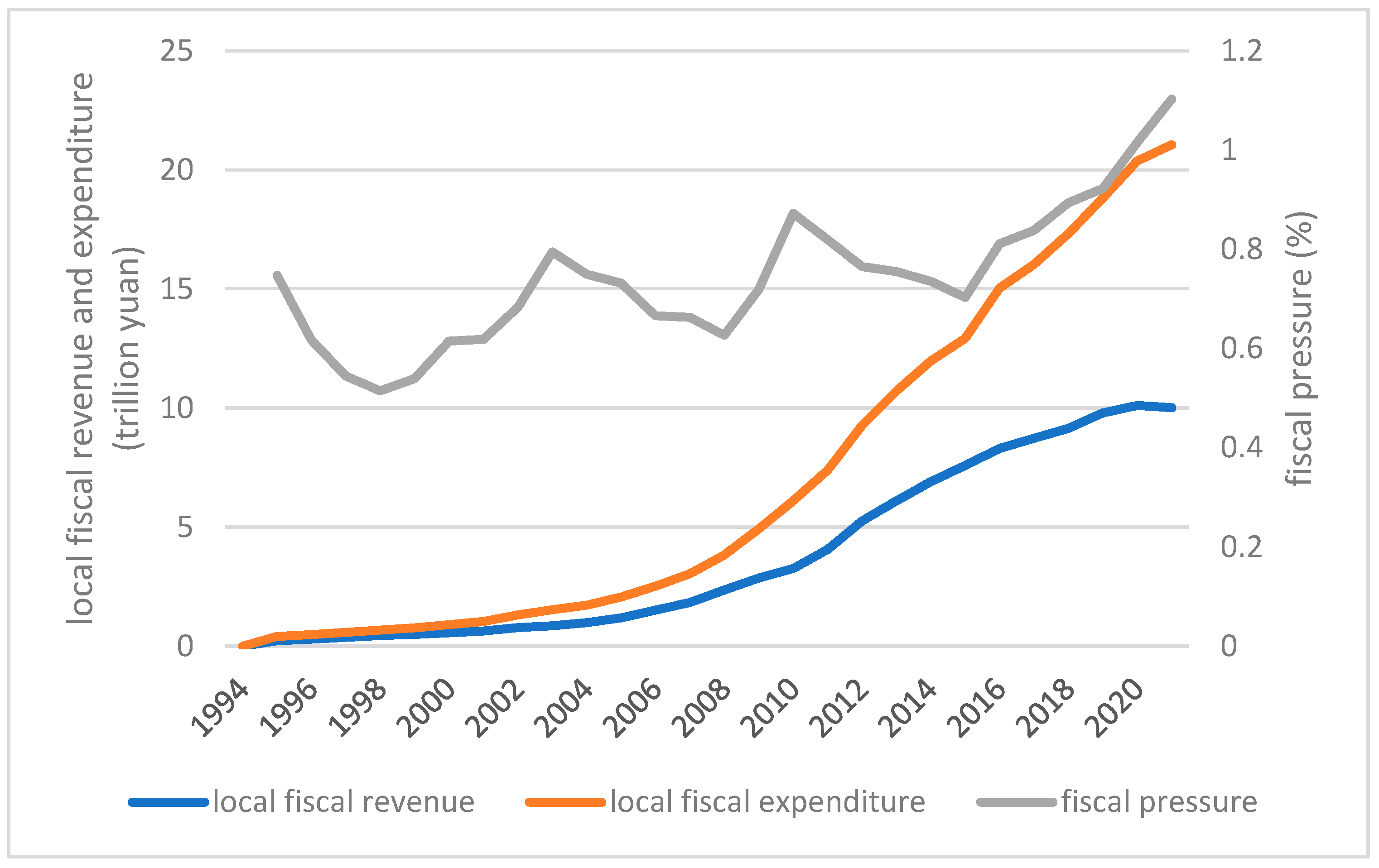

At present, scholars have not yet reached an agreement on how to measure local fiscal pressure. In the research, most scholars use “the gap between fiscal revenue and expenditure” to measure the fiscal pressure of local governments, including the difference method and ratio method. The former measures local fiscal pressure using the difference between regional fiscal expenditure and fiscal revenue, while the latter measures fiscal pressure by the ratio of the difference between regional fiscal expenditure and revenue to total fiscal revenue [

2]. However, this method of directly using statistical data to calculate the local fiscal gap ignores the role of the transfer payment system, and can easily cause endogenous problems in the research. To solve this problem, scholars have measured fiscal pressure through quasi-natural experiments of policy shocks. For example, scholars have used the rotated minister system [

15], the reform of abolishing agricultural tax [

16,

17,

18], the reform of income tax sharing [

19], the “business tax to VAT” policy [

20], the real estate purchase restriction policy and the reform of educational authority as exogenous shocks of fiscal pressure [

21,

22], and constructed quasi-natural experiments to measure the changes in fiscal pressure of local governments.

Regarding the environmental effect of fiscal pressure, scholars have mainly discussed the impact of local government behavior on environmental quality from the perspective of fiscal pressure. Under the promotion incentive mechanism of “political tournament” in China, the local government tended to prioritize to economic development over environmental protection [

23,

24]. When faced with fiscal pressure, to promote local economic development and thus increase fiscal revenue, the local government is motivated to relax environmental control and adopt the “race to the bottom” strategy in exchange for economic growth [

25,

26]. Specifically, the increase in local fiscal pressure leads to an increase in the local industrial pollution level [

27], a significant increase in local carbon emissions [

22] and a deterioration in local air quality [

28]. The greater the local fiscal pressure, the more obvious the boundary effect of air pollution [

29]. In addition, under fiscal pressure, the local government relaxes environmental regulations. On the one hand, it can attract polluting enterprises with a high output value to settle down and develop locally [

30]. On the other hand, it is beneficial to support local industrial enterprises with key tax sources to expand their production scale. This behavior is conducive to achieving economic growth and fiscal revenue targets, but it also leads to environmental pollution. It also reduces the environmental governance efficiency of the local government. The greater the fiscal pressure, the lower the local government’s environmental governance efficiency [

31].

Based on the related literature, it can be observed that the existing research mainly has the following two shortcomings. On the one hand, the existing research on the environmental effects of local fiscal pressure was conducted mostly from a macro-enterprise perspective and rarely from the perspective of micro-enterprises. On the other hand, most related studies have paid attention to the pollution effect of fiscal pressure from the perspective of pollution emission and little attention has been paid to pollution control. Compared with the previous literature, the potential contributions of this paper are mainly reflected in the following aspects.

First, from the perspective of micro-enterprises, based on the data of A-share-listed companies from heavily polluting industries in China, this paper systematically studied the impact of local fiscal pressure on the environmental protection investment of enterprises and its internal mechanism. The existing literature has paid little attention to the relationship between local fiscal pressure and enterprise environmental protection investment. This paper innovatively discusses the relationship between them, enriching the related research on local fiscal pressure and environmental governance.

Second, it can be seen from previous studies that COVID-19 has had a significant impact on local public finance. The COVID-19 epidemic has been used as an exogenous shock to reflect the change in local fiscal pressure, which further enriches the measurement method of fiscal pressure. This work not only overcomes the endogenous problem of measuring local fiscal pressure, but also reflects the current situation with the latest data.

Third, this paper further verifies the key role of public finance in environmental governance by placing local fiscal pressure, government behavior and enterprise environmental protection investment into the unified analysis framework. The conclusion of this paper is significant to the future environmental governance of China, and it is necessary to focus on solving the local fiscal pressure dilemma to increase green investment and achieve green development.

2.2. Theoretical Hypotheses

In the face of fiscal pressure, local governments often choose the way of “increasing revenue and cutting expenditure” to alleviate the pressure from the income side and the expenditure side, respectively. In terms of revenue, scholars generally believe that the local government’s market access to fiscal revenue is the main approach to deal with fiscal pressure. Research has investigated in depth the relationship between fiscal pressure and local government financial resources cultivation, local government debt issuance, tax collection and administration, non-tax revenue collection and management. These behaviors are common choices for local governments to alleviate fiscal pressure.

First of all, as for the cultivation of financial resources, under the “pressure-type” fiscal incentives, local governments increase fiscal revenue and expand the tax base by vigorously developing the secondary industry and even relaxing environmental regulations to introduce enterprises with overcapacity [

32]. The cultivation of financial resources by promoting local economic growth, the so-called “releasing water to raise fish”, does help local governments to fundamentally solve the fiscal pressure problem, but it often takes a long time to cultivate financial resources, which cannot alleviate the fiscal pressure caused by the COVID-19 epidemic in a short time.

Secondly, in terms of debt issuance, there are two limitations in dealing with fiscal pressure by issuing local government debt. On the one hand, the local government debt scale is subject to limited management, and it cannot exceed the approved limit. On the other hand, there is a certain lag in alleviating fiscal pressure through debt expansion [

33].

Thirdly, as for the land transfer system, some scholars consider that land transfer is an important channel for local governments to ease fiscal pressure [

34], but some scholars hold different opinions. The study by Fan (2015) found that the real reason for local governments to sell land is not fiscal pressure, but rather the impulsive investment behavior of local governments [

15]. Faced with fiscal pressure, local governments will even reduce the transfer of industrial land [

35].

Fourthly, in terms of tax collection and management, strengthening the tax collection and management of enterprises and transferring fiscal pressure to the enterprises within their jurisdiction are important ways for local governments to increase fiscal revenue and ease fiscal pressure [

16]. However, strengthening tax collection and management undoubtedly increase the tax burden of enterprises, which is contrary to the tax reduction policy that China is vigorously promoting at present.

Finally, in the collection and management of non-tax revenue, local governments have the authority to set up and collect non-tax revenue, and can adjust the scale and intensity of non-tax revenue collection and management according to the current fiscal revenue and expenditure situation [

36]. It can even be said that non-tax revenue is one of the areas where the local governments have the highest flexibility, the strongest intervention ability and the least restriction on collection and management among all financing means [

37]. Therefore, non-tax revenue has become an important channel for local governments to relieve fiscal pressure [

19].

To sum up, this paper considered that extending the “grab hand” to enterprises and strengthening the collection and management of non-tax revenue are effective policy tools for local governments to alleviate fiscal pressure in the short term. If the local government narrows the gap between fiscal revenue and expenditure by strengthening the collection and management of non-tax revenue, it will undoubtedly increase the non-tax burden on enterprises [

19]. Non-tax expenditure, as an important part of enterprise expenditure flow, will reduce the cash flow and profitability of enterprises. The enterprises will coordinate the relationship between private marginal income and marginal cost according to their own profit target and financial situation. Due to the typical positive externality of environmental protection behavior, the private marginal income of environmental protection investment will be lower than the private marginal cost for enterprises. Therefore, enterprises are incentivized to distort the investment proportion of their production factors, tilt the production factors to the economic activities and reduce the investment in non-economic activities, such as environmental protection investment. In other words, strengthening the collection and management of non-tax revenue will lead enterprises to adjust the allocation of resources between their economic activities and non-economic activities, resulting in a crowding-out effect on environmental protection investment. Based on this, the following hypothesis is presented:

Hypothesis 1. Local governments will strengthen the collection and management of non-tax revenue under fiscal pressure, leading enterprises to reduce their environmental protection investment.

In terms of fiscal expenditure, local governments can also ease the fiscal pressure by “cutting expenditure”. Especially in western countries, because of the flexibility of the budget system, local governments have more room to adjust the scale of fiscal expenditure flexibly. Scholars have found that, under fiscal pressure, the scale of local government expenditure shows a significant downward trend [

38,

39,

40]. However, in China, the incentive from the economic growth target under the “political tournament” and the budget constraint caused by the increasing public demand make it difficult to flexibly change the local fiscal expenditure level. The fiscal expenditure of local government has a significant downward rigidity [

41]. Therefore, in the face of fiscal pressure, the space for local governments to control simply by reducing the scale of fiscal expenditure is relatively limited, and they are more dependent on the adjustment of the fiscal expenditure structure [

42].

First of all, fiscal pressure leads to the distortion of the public expenditure structure of local governments, showing a bias towards “emphasizing production and neglecting people’s livelihood” [

43]. Fiscal productive expenditure is conducive to promoting the development of the local economy, thus bringing more tax sources. Therefore, for local governments, productive expenditures are often characterized by exclusive marginal income, high economic efficiency and a short investment cycle. On the contrary, the expenditure on people’s livelihood shows a significant income spillover effect, and it takes a long time to become effective. Under fiscal pressure, the local governments shift their limited financial funds from the people’s livelihood to the production field by adjusting the expenditure structure, prioritizing the realization of economic and tax targets. Secondly, among all types of people’s livelihood expenditures, the supply order of public goods, such as education, medical care and employment, still takes precedence over environmental governance [

44]. Therefore, to alleviate fiscal pressure, local governments will further reduce environmental-protection-related expenditures and reduce environmental subsidies to enterprises.

Environmental protection subsidies are important tools for environmental regulation in China. It is a special subsidy provided by the government to encourage enterprises to actively invest in environmental protection, which is beneficial to internalizing the externalities of environmental governance [

45]. According to the “Several Provisions on Strengthening the Management of Environmental Protection Subsidy Funds”, the environmental protection subsidy funds are earmarked for the environmental protection investment projects of enterprises, such as key pollution sources control and comprehensive environmental management. Environmental subsidies provide direct financial support for enterprises to participate in environmental governance activities and reduce the cost of environmental protection investment [

46]; at the same time, they reduce the occupation of production funds by environmental protection investment and alleviate the shortage of funds for enterprises. The environmental subsidies are conducive to internalizing the positive externalities of enterprise environmental governance, thus encouraging enterprises. Once the government reduces the expenditure of environmental protection subsidies under fiscal pressure, the cash flow that enterprises can directly invest in environmental protection investment is reduced, and the enterprises are expected to reduce environmental protection investment. Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2. Local governments will reduce environmental subsidies under fiscal pressure, leading enterprises to reduce their environmental protection investment.