Mapping the Knowledge Structure and Unveiling the Research Trends in Social Entrepreneurship and Inclusive Development: A Bibliometric Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Social Entrepreneurship

2.2. Inclusive Development

2.3. Bibliometric Analysis

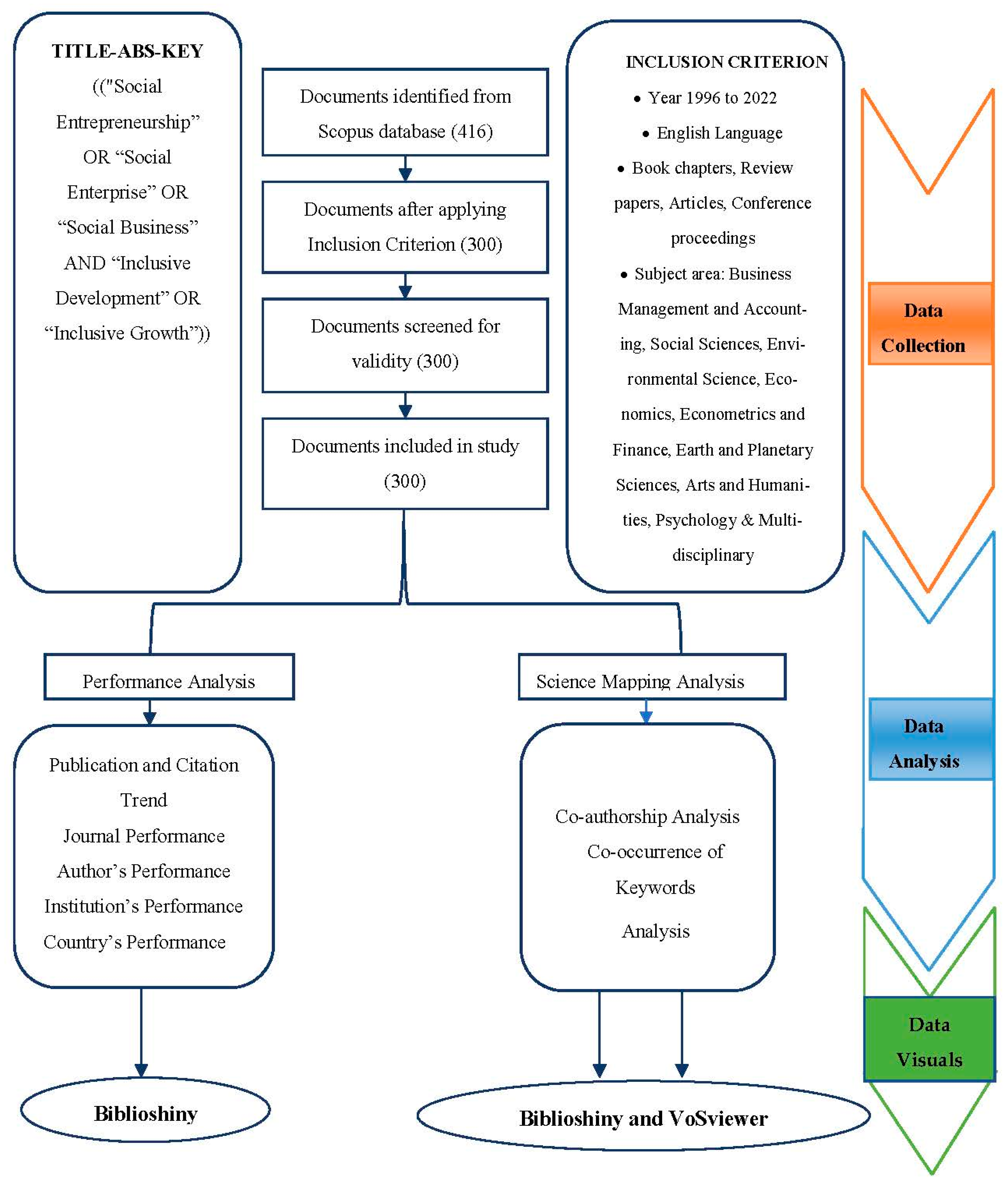

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

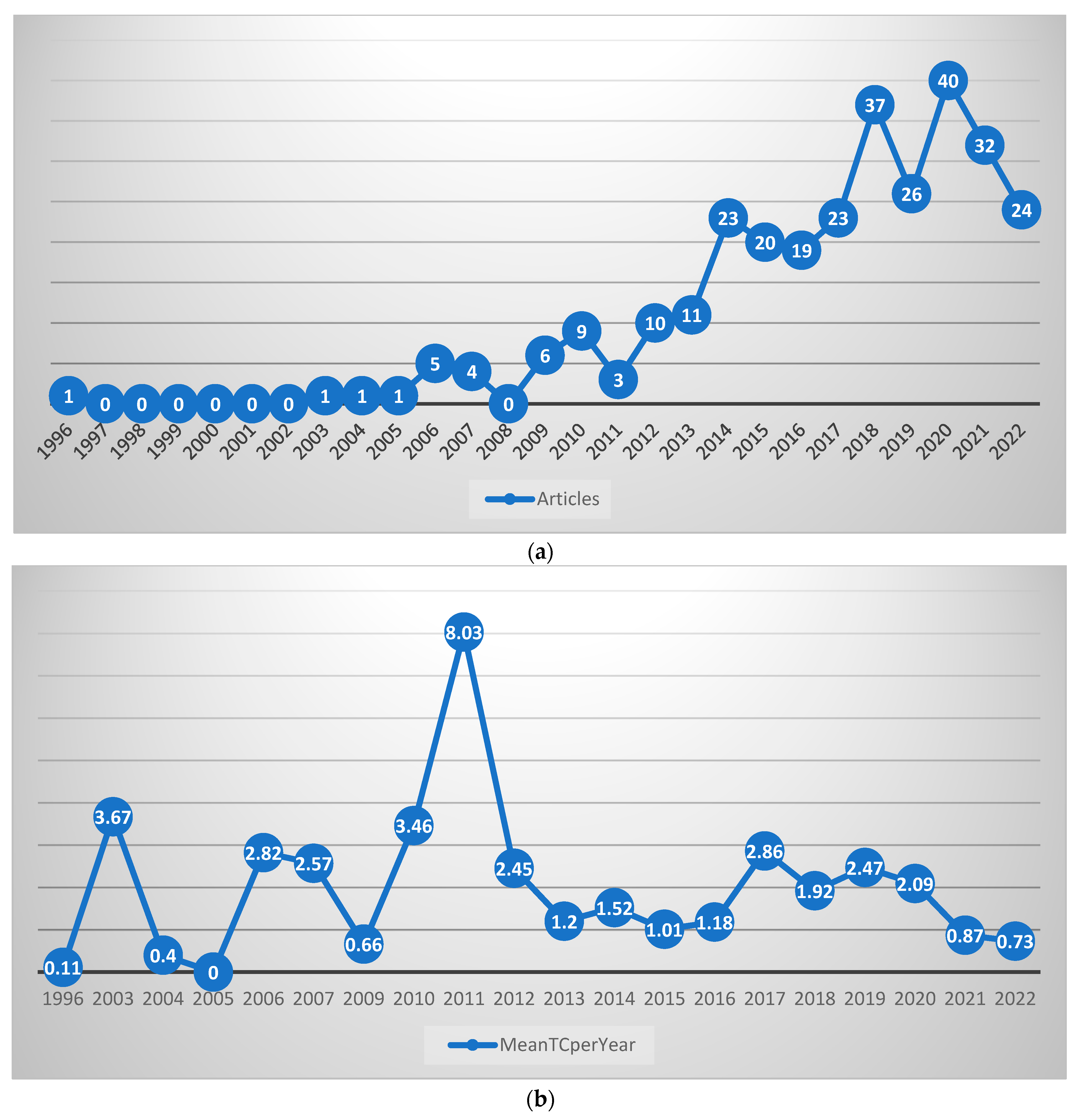

4.1. Performance Analysis

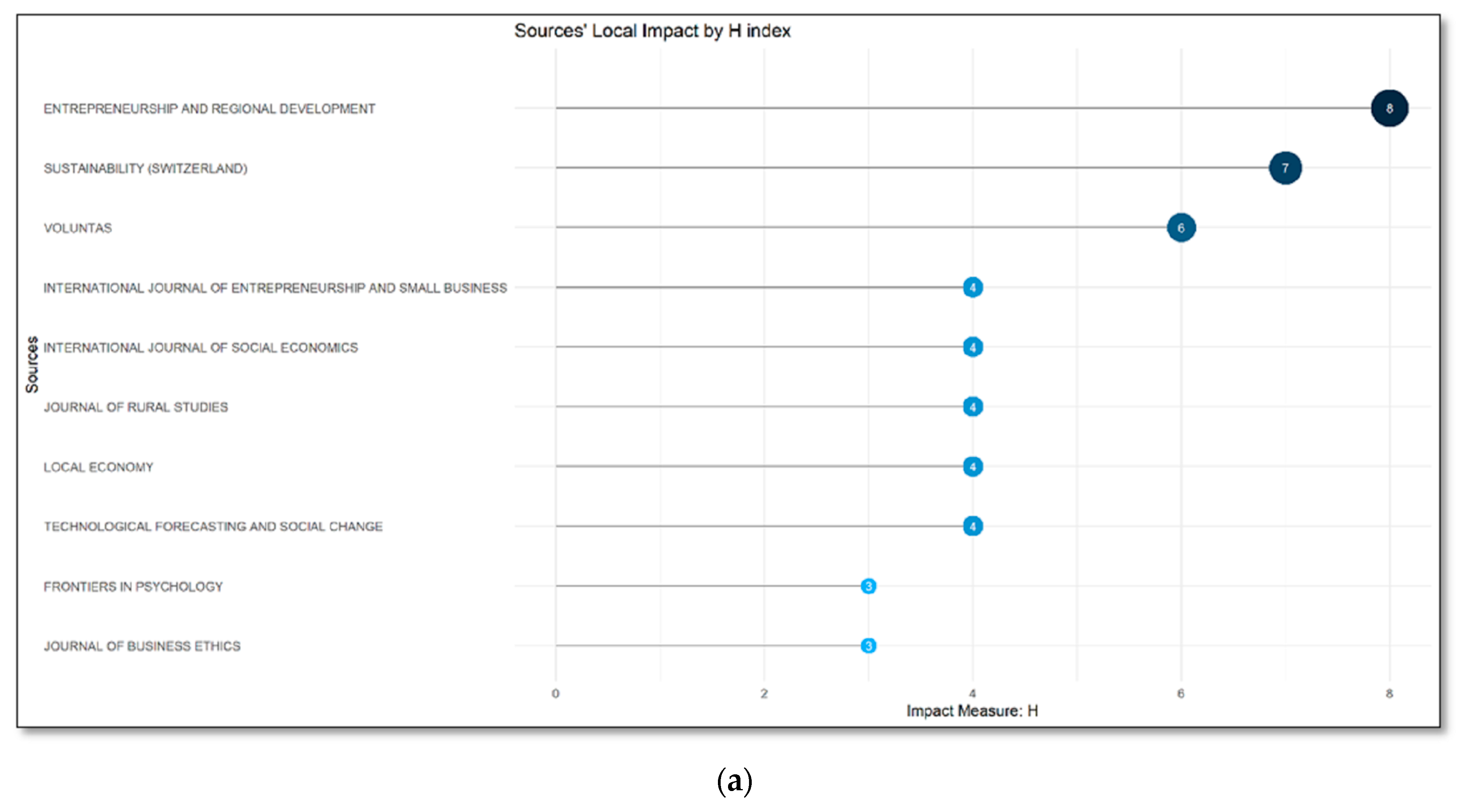

4.2. Most Influential Journals

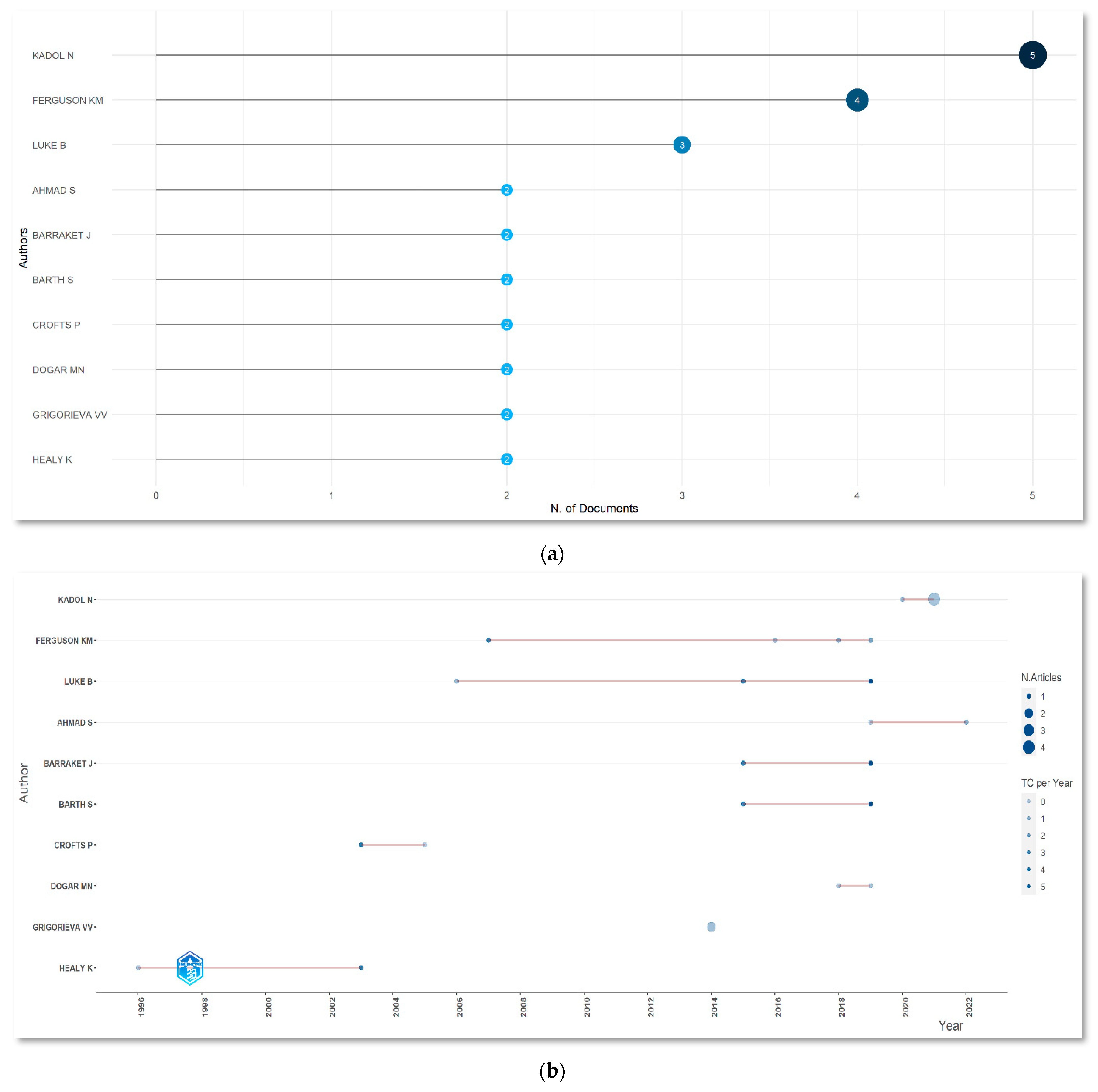

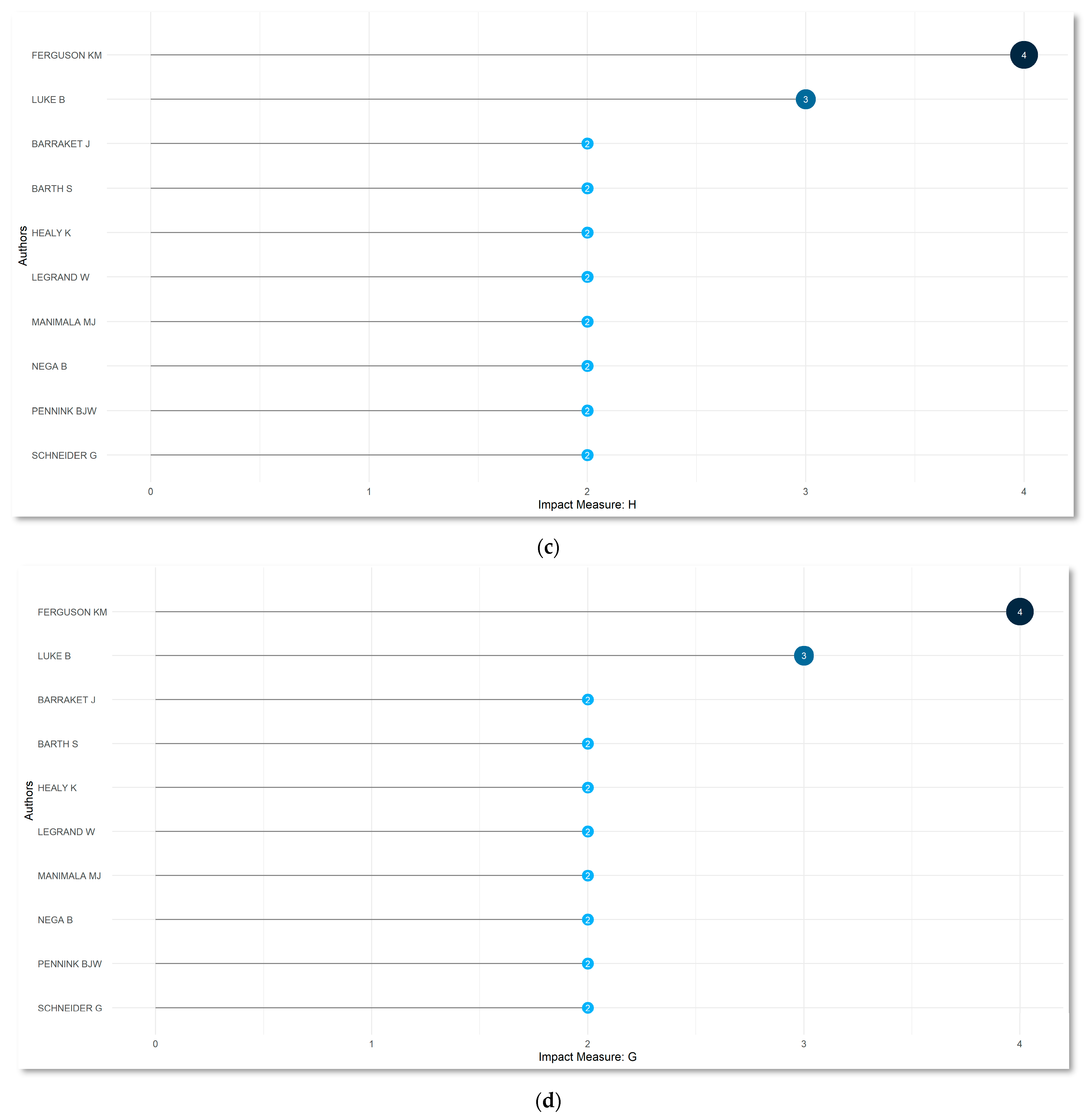

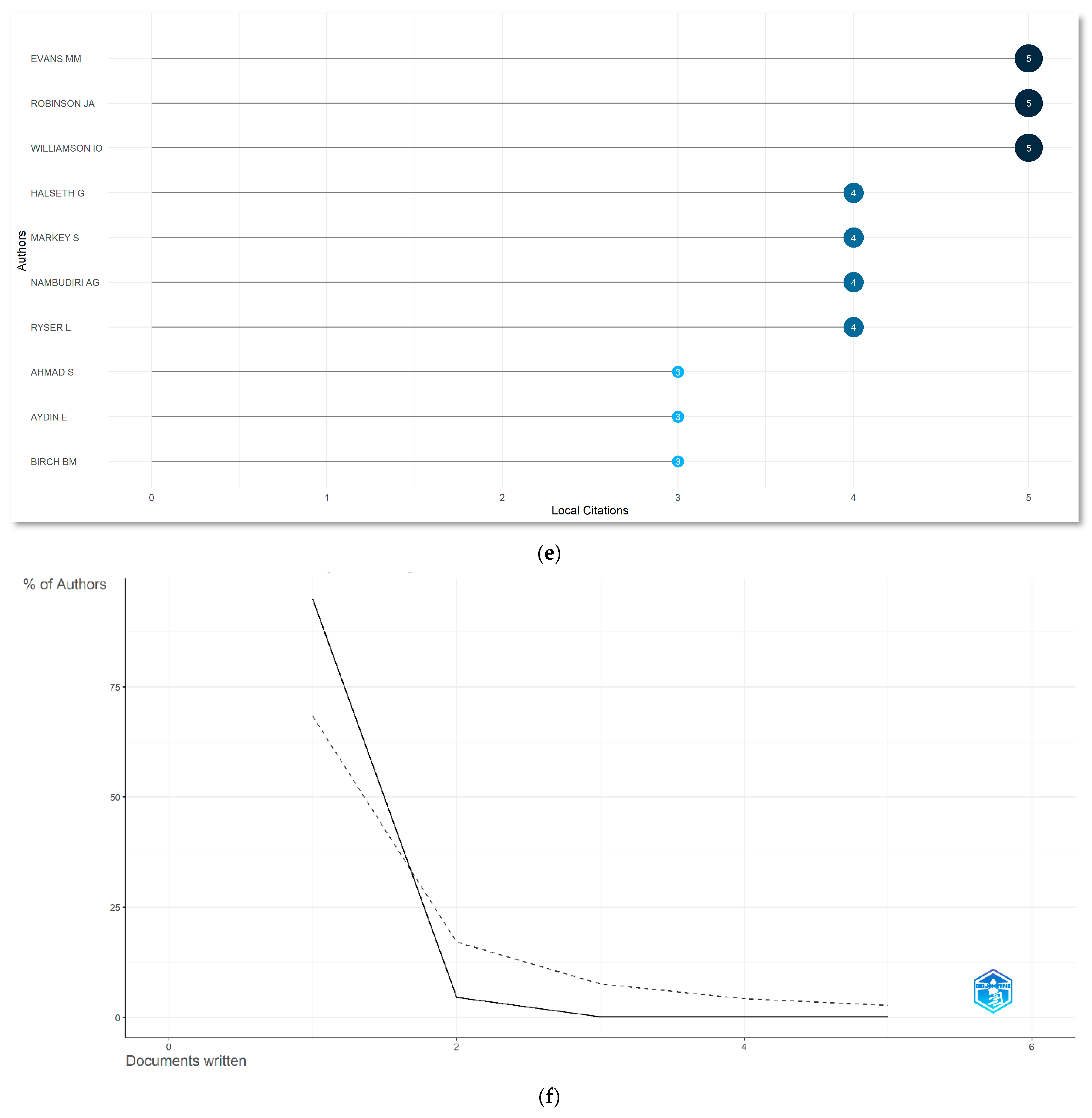

4.3. Most Influential Authors

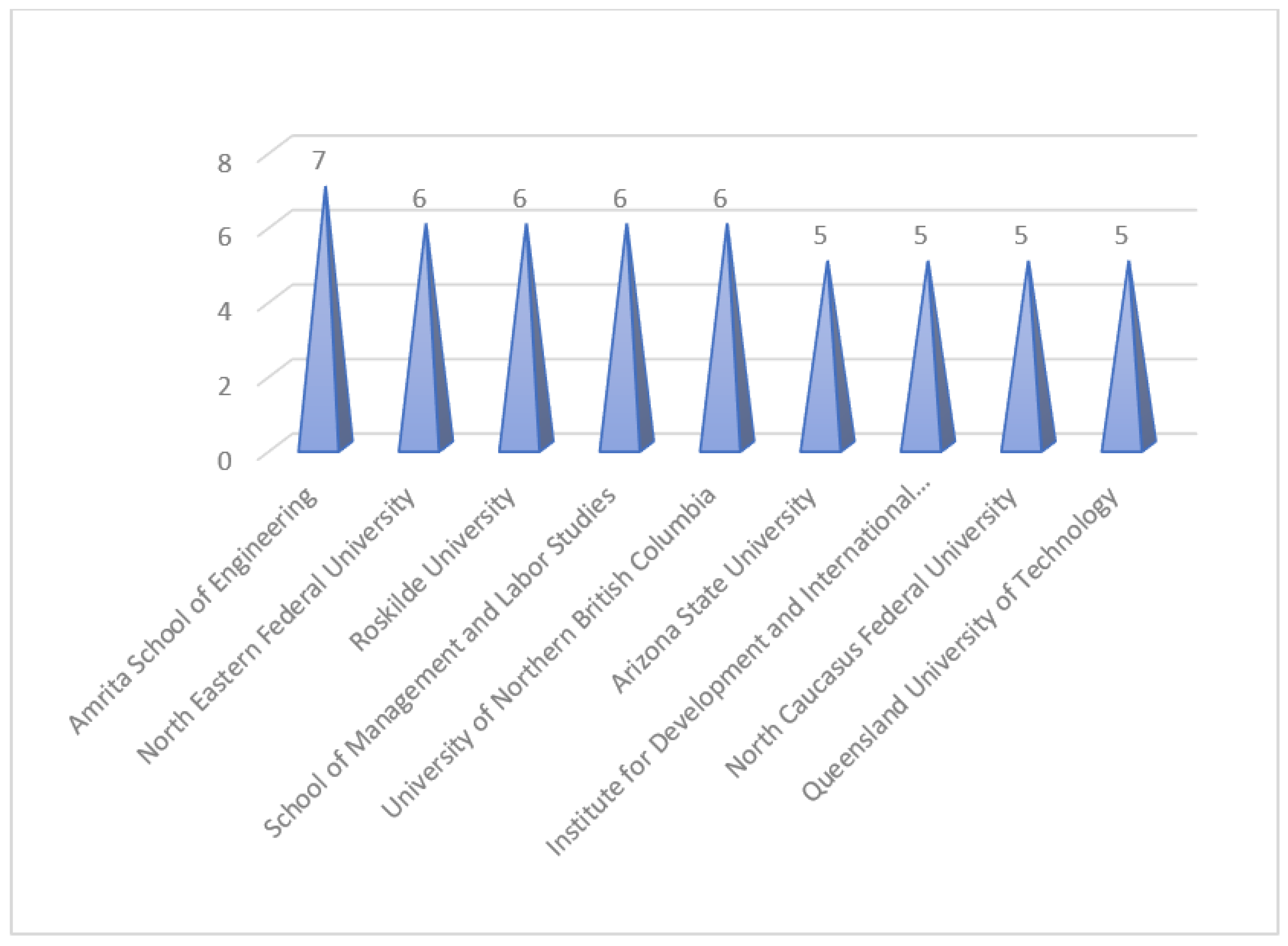

4.4. Most Productive Affiliations

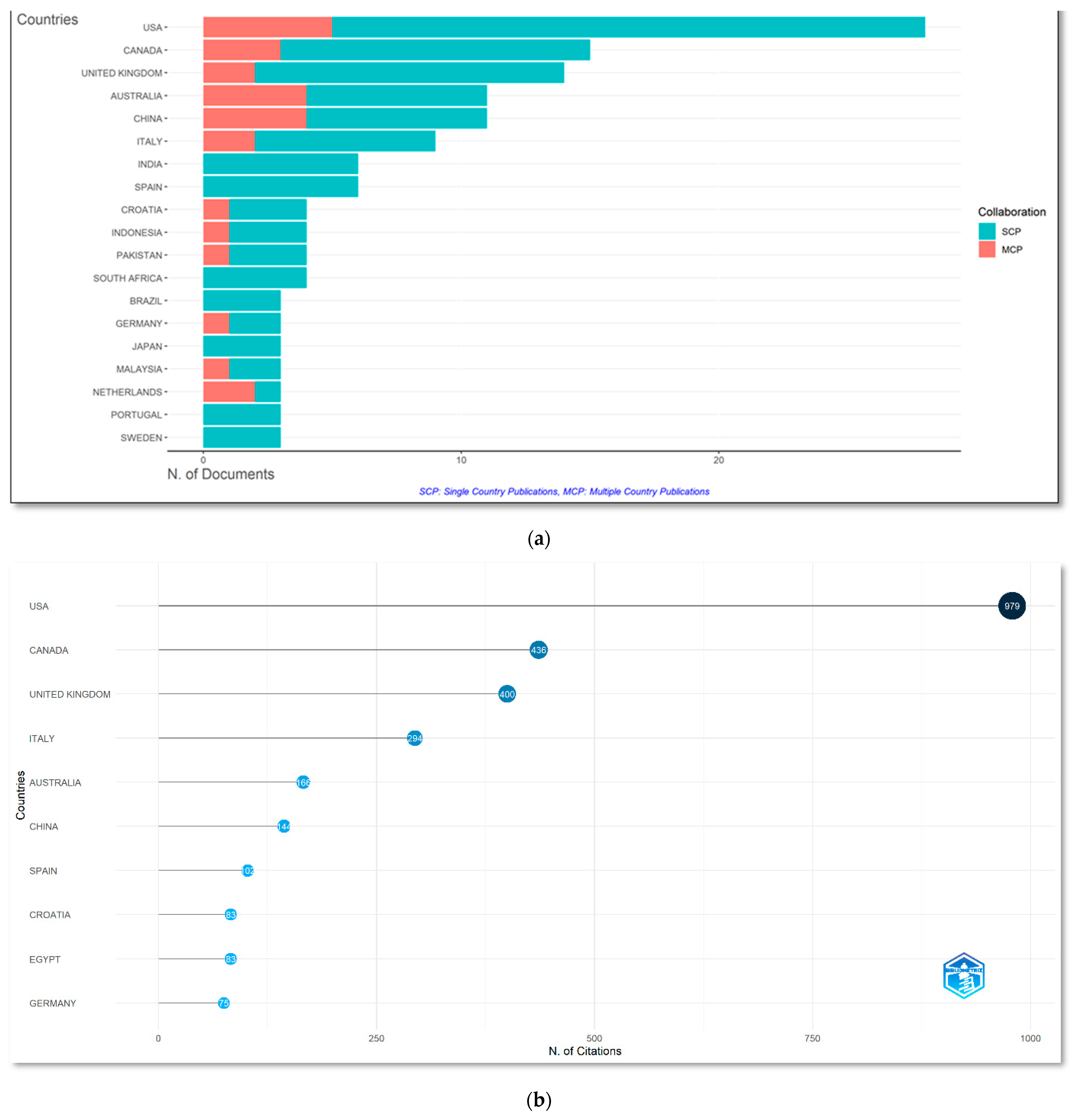

4.5. Most Contributing Countries

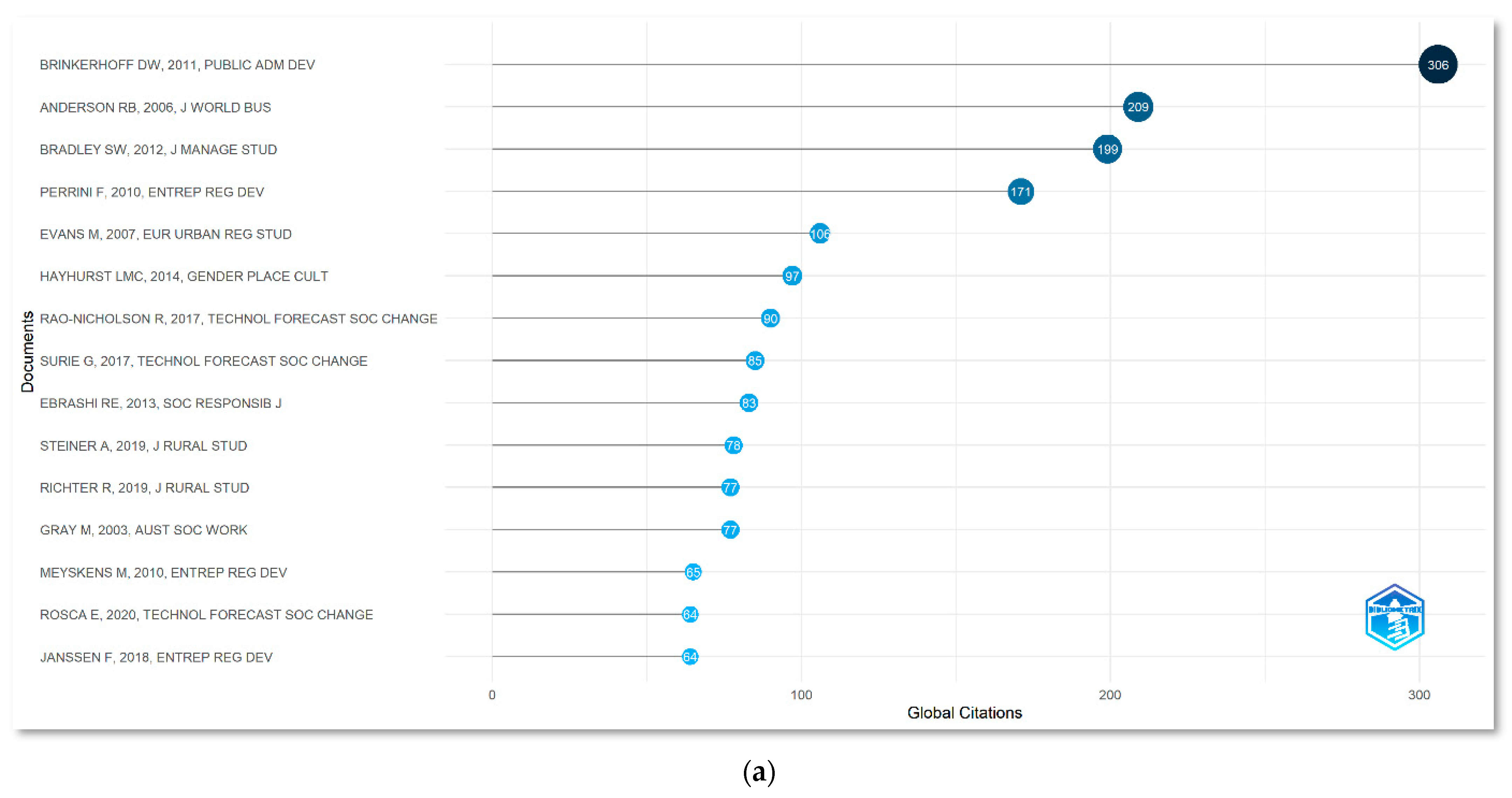

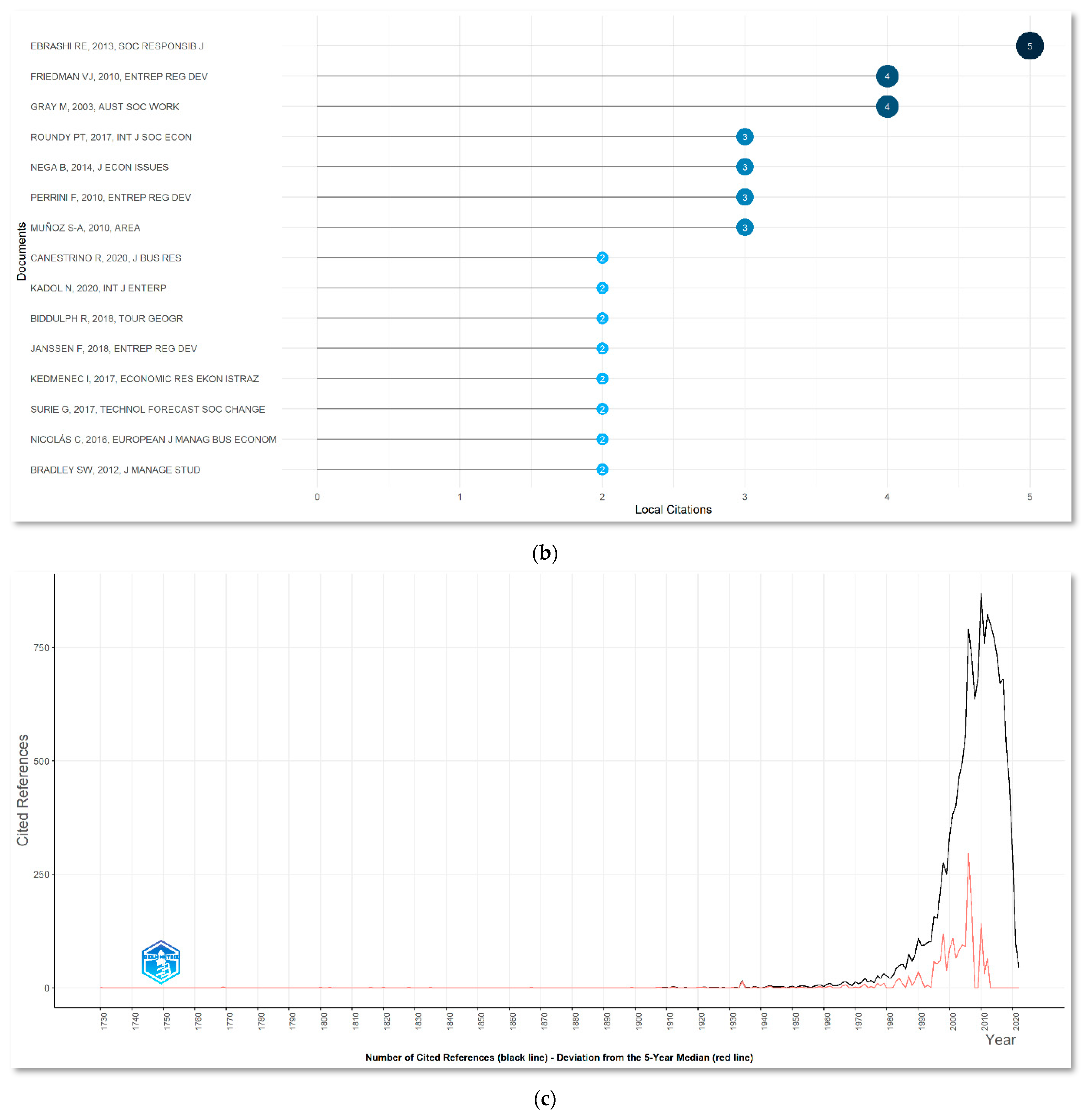

4.6. Document Analysis

Science-Mapping Analysis

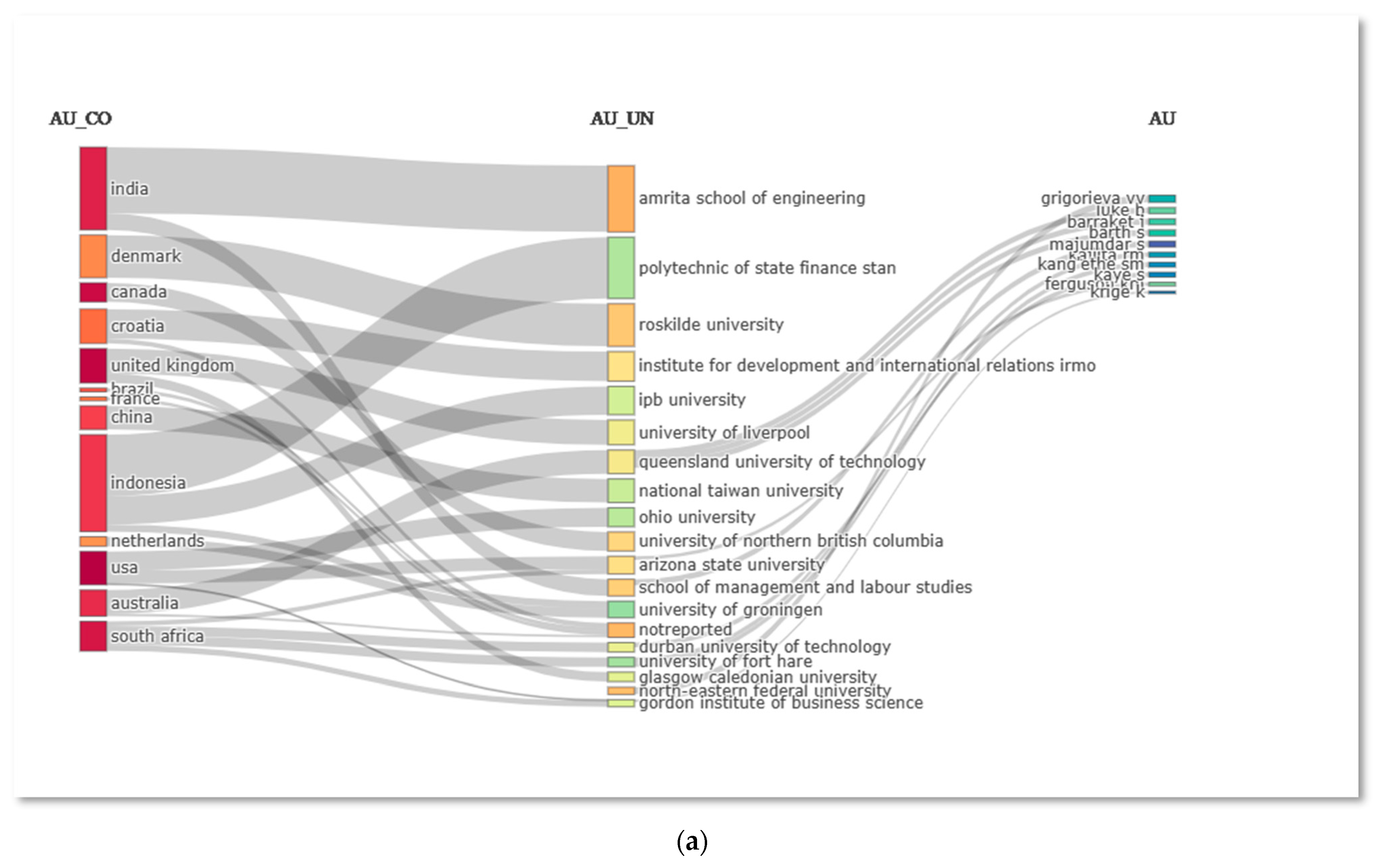

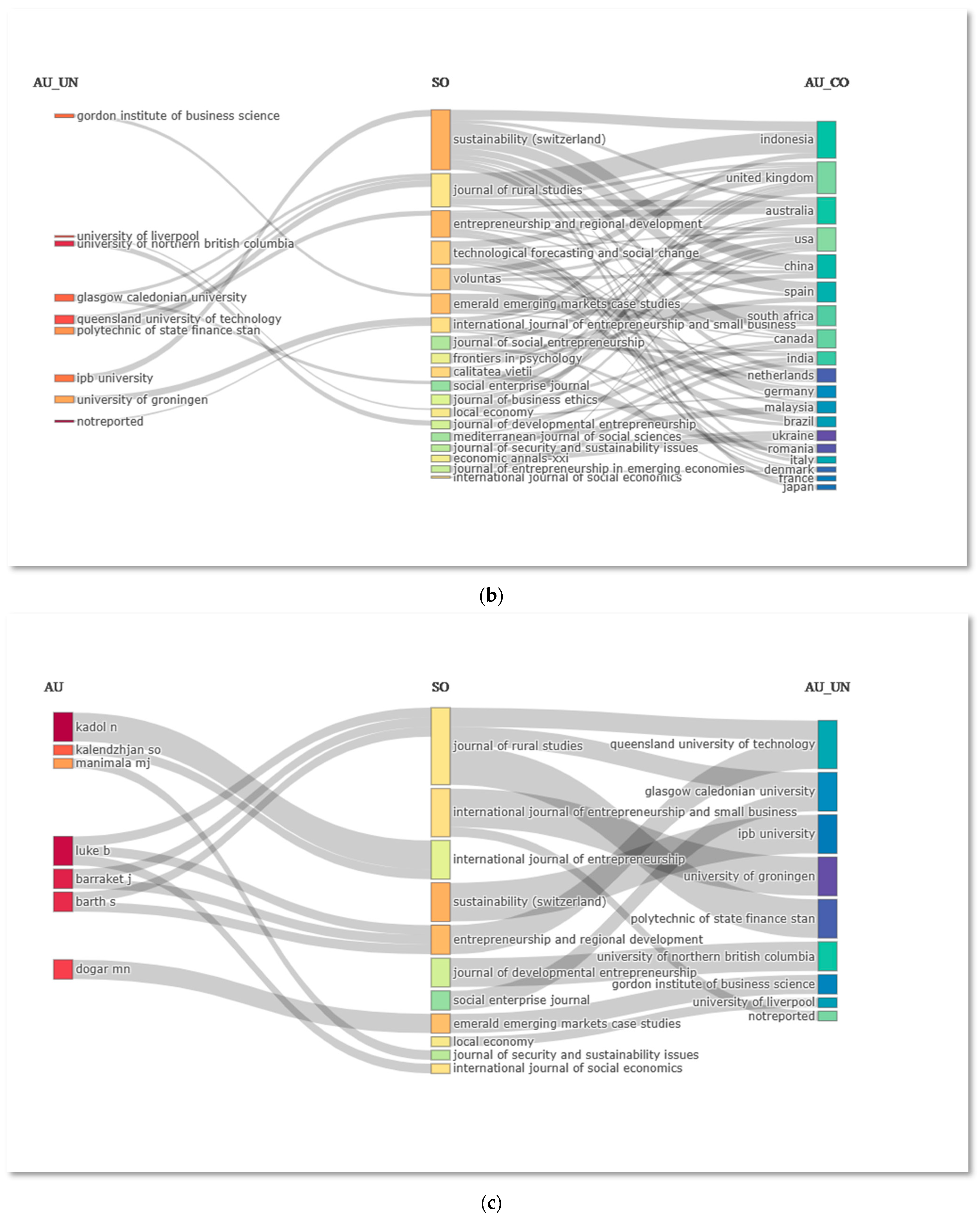

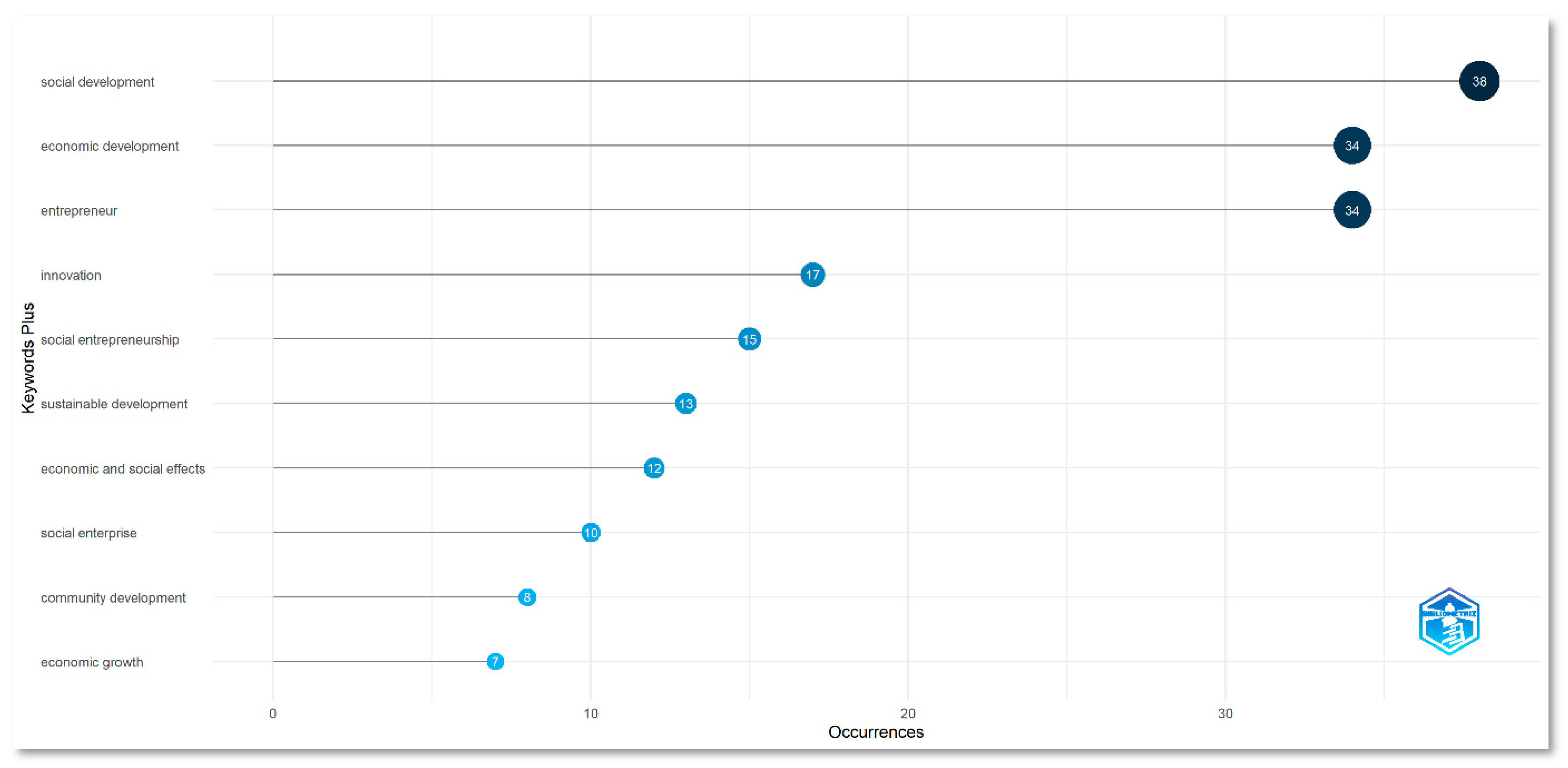

4.7. Co-Authorship Analysis

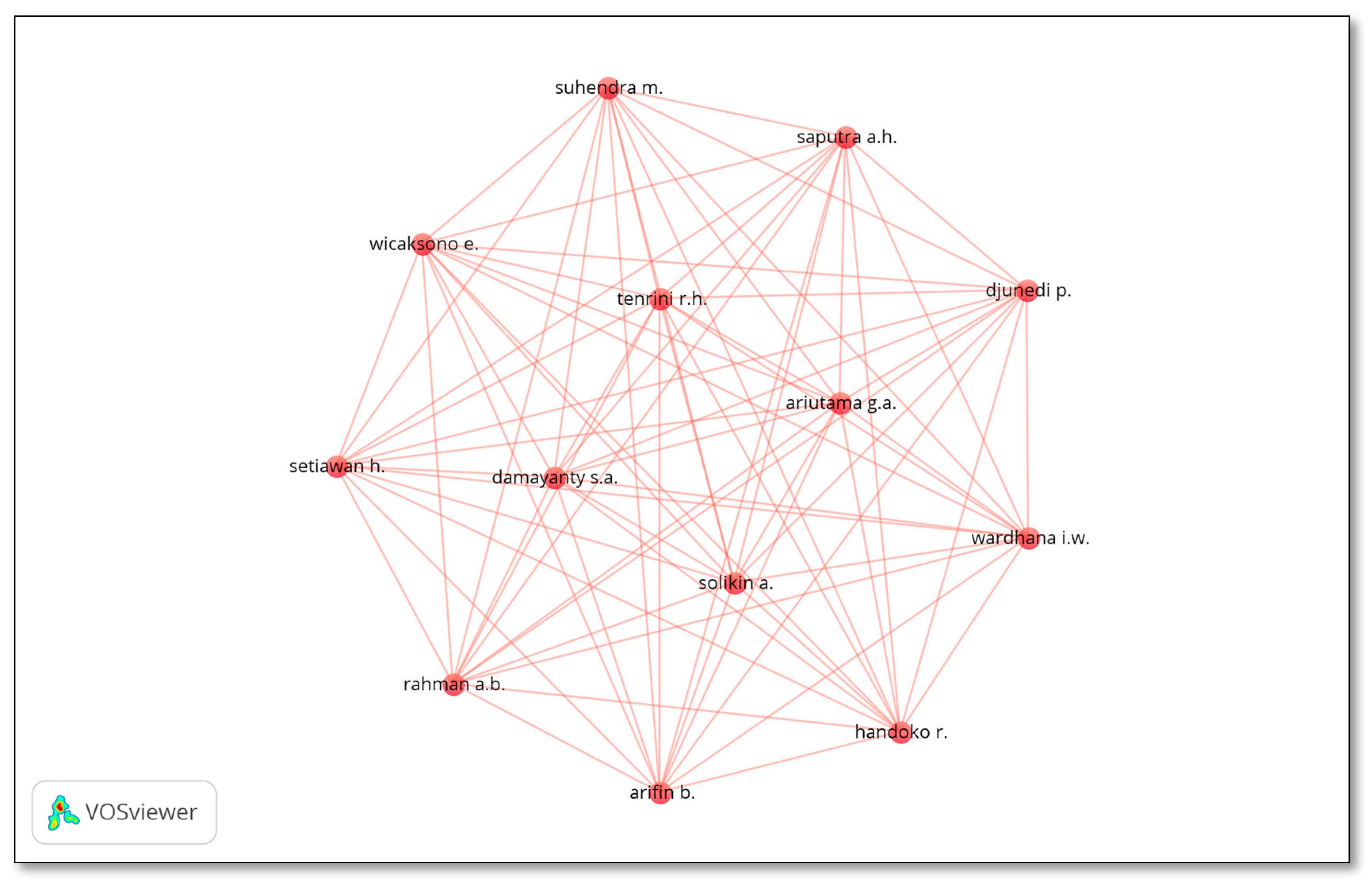

4.7.1. Centered on Authors

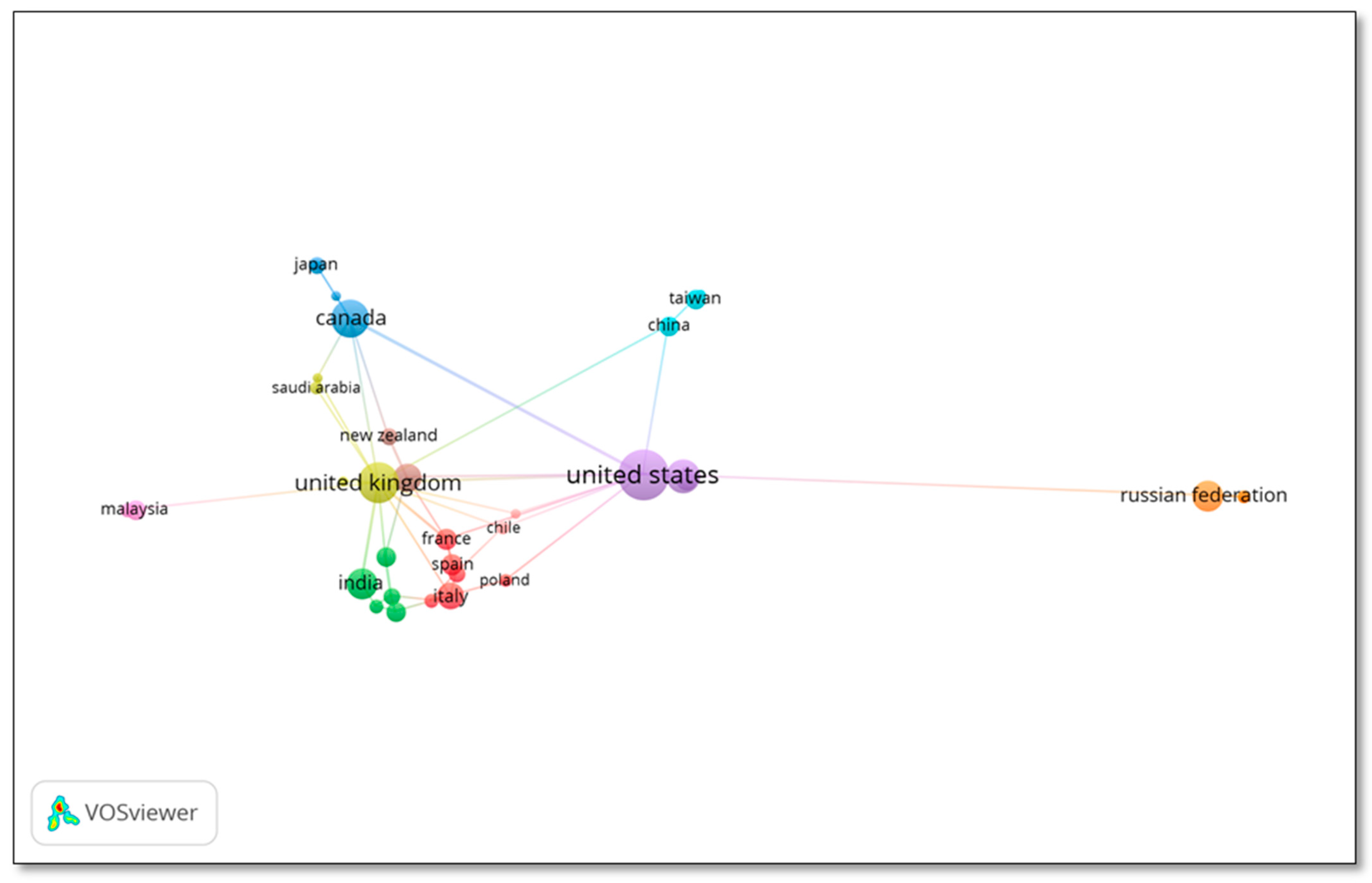

4.7.2. Centered on Countries

4.7.3. Centered on Organizations

5. Discussion

5.1. General Trends in the Literature on Social Entrepreneurship and Inclusive Development

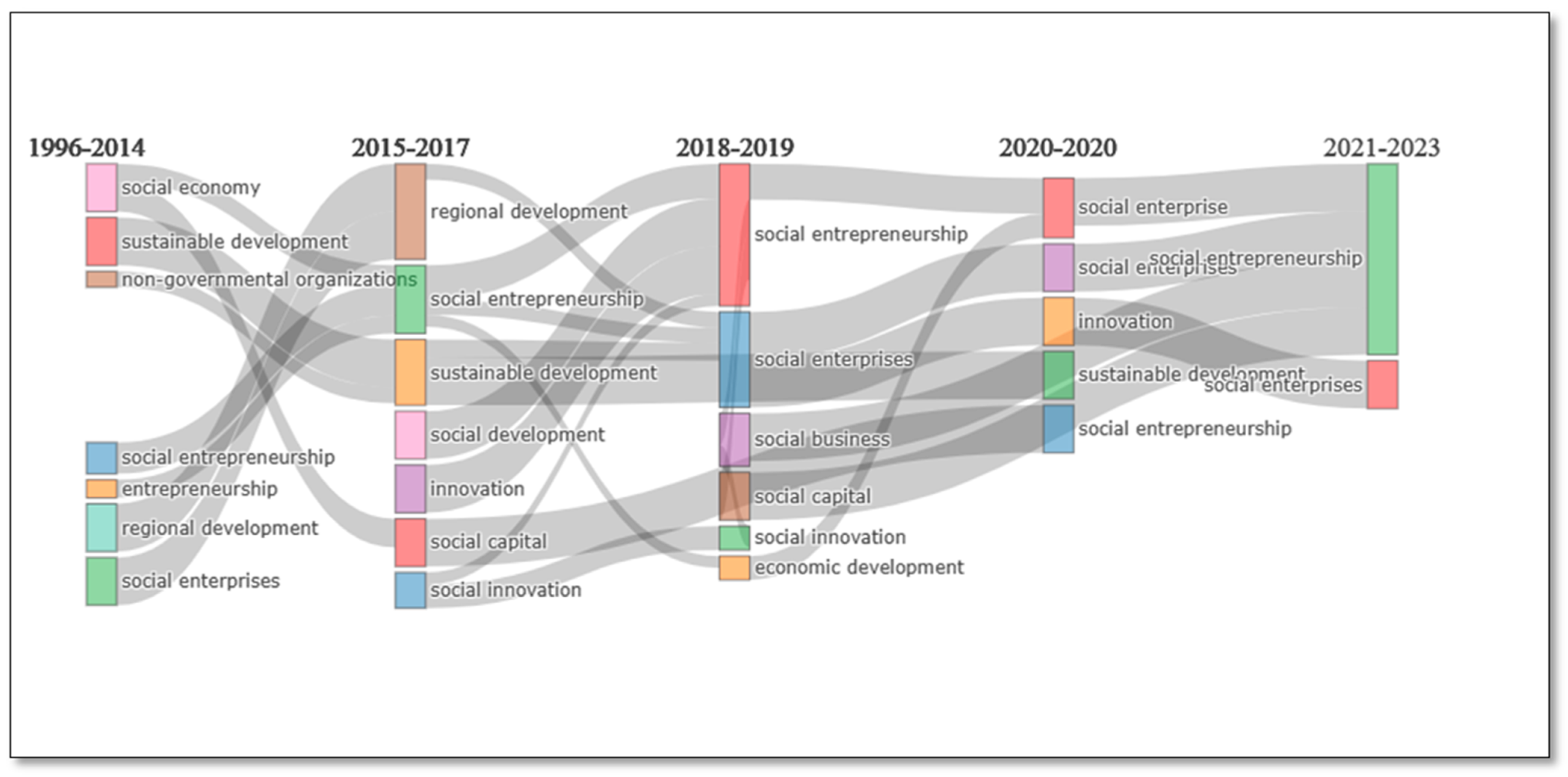

5.2. Co-Occurrence of Keywords Analysis

5.3. Thematic Evolution

5.4. Future Research Directions

- (a)

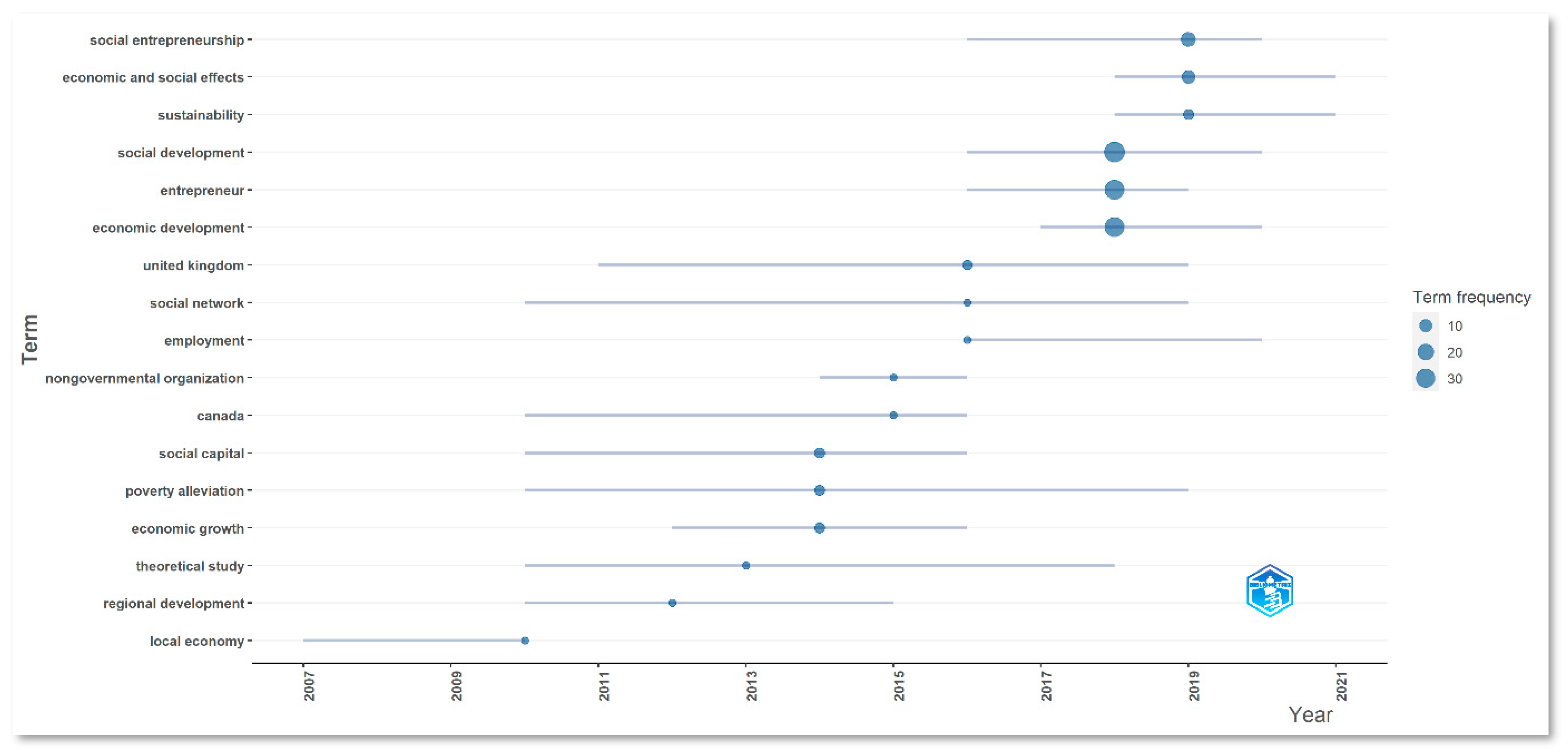

- Economic and Social Effects—Social entrepreneurship and inclusive development has emerged as the most popular topic. Social entrepreneurship, a rapidly developing field that uses an entrepreneurial approach to achieve social and economic effects, is essential for inclusive development and helps to strengthen a nation’s economy and societal fabric [71]. Social enterprises have the power to advance sustainability, provide cutting-edge services and goods and inspire optimism for the future. “Almost 200 million individuals are already involved in social entrepreneurship projects worldwide”, according to the European Commission, and that number is rising [72]. The creation of jobs, particularly for the less fortunate or marginalized segments of society, is one of the most evident and striking effects of social entrepreneurship. “Social enterprises operate as an intermediary between unemployment and the open labor market”, according to Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. Large-scale worker reintegration into the labor market has enormous social and economic benefits, at least from a simple quantitative standpoint. The concepts of social entrepreneurs and social enterprises are relatively hazy, despite the beneficial effects they have on the economy. For instance, there is no unified definition of social entrepreneurship [73]. Our data show that it started to be widely utilized in 2019 and has continued along this path (Figure 15).

- (b)

- Sustainable Development—The most recent set of keywords used by researchers in social entrepreneurship and inclusive development ranked it third. Social entrepreneurship offers two paths: ‘social innovation’ and ‘scaling of social innovation’—to create a solution for Sustainable Development Goals. “Young social entrepreneurs play a significant part in advancing the Sustainable Development Goals of the 2030 Agenda”, according to the UN. As a result, social enterprises have become viable options for addressing social issues through entrepreneurial prospects [74]. In addition, social entrepreneurship—the use of entrepreneurial qualities like ”creativity, innovation, and motivation along with the determination to address society’s most pressing social problems”—is necessary to face the difficulties of sustainable development [75,76,77,78]. Although sustainable development is not a new topic, interest in it has significantly increased recently, particularly since 2019, according to our statistics (Figure 15), and it is anticipated to continue to be a buzz topic, supporting social entrepreneurship and inclusive development.

- (c)

- Social Development—This is yet another term that has recently appeared in academic works on social entrepreneurship and inclusive development. As opposed to an approach that prioritizes immediate financial gains for entrepreneurs, social entrepreneurship is a process that sparks social change and meets critical societal needs [79]. In comparison to other forms of entrepreneurship, social entrepreneurship is thought to place a substantially larger premium on advancing societal value and development than on maximizing financial gain [48]. As a type of social innovation, “social entrepreneurship is good for society because it can benefit a variety of stakeholders, including businesses and socially targeted groups. For businesses, social entrepreneurship can increase revenues and profits, customer volume, loyalty and satisfaction and business reputation. For the government, it can decrease unemployment and social exclusion. According to our research, it first became widely used in 2018 and has kept going in the same direction since then” (Figure 15).

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Austin, J.; Stevenson, H.; Wei–Skillern, J. Social and Commercial Entrepreneurship: Same, Different, or Both? Entrep. Theory Pract. 2006, 30, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chell, E.; Spence, L.J.; Perrini, F.; Harris, J.D. Social Entrepreneurship and Business Ethics: Does Social Equal Ethical? J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 133, 619–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Banks, J.A. The Sociology of Social Movements; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Alvord, S.H.; Brown, L.D.; Letts, C.W. Social Entrepreneurship and Societal Transformation: An Exploratory Study. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2004, 40, 260–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pless, N.M. Social Entrepreneurship in Theory and Practice—An Introduction. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 111, 317–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sassmannshausen, S.P.; Volkmann, C. A Bibliometric Based Review on Social Entrepreneurship and Its Establishment as a Field of Research; Schumpeter Discussion Papers. 2013. Available online: https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/97203/1/748707158.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Conway Dato-on, M.; Kalakay, J. The Winding Road of Social Entrepreneurship Definitions: A Systematic Literature Review. Soc. Enterp. J. 2016, 12, 131–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey-Martí, A.; Ribeiro-Soriano, D.; Sánchez-García, J.L. Giving Back to Society: Job Creation through Social Entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2067–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannampuzha, M.; Hockerts, K. Organizational Social Entrepreneurship: Scale Development and Validation. Soc. Enterp. J. 2019, 15, 290–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huda, M.; Qodriah, S.L.; Rismayadi, B.; Hananto, A.; Kardiyati, E.N.; Ruskam, A.; Nasir, B.M. Towards Cooperative With Competitive Alliance: Insights Into Performance Value in Social Entrepreneurship. Available online: https://www.igi-global.com/chapter/towards-cooperative-with-competitive-alliance/www.igi-global.com/chapter/towards-cooperative-with-competitive-alliance/208413 (accessed on 22 February 2023).

- Bygrave, W.; Minniti, M. The Social Dynamics of Entrepreneurship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2000, 24, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban-Santos, L.; García Medina, I.; Carey, L.; Bellido-Pérez, E. Fashion Bloggers: Communication Tools for the Fashion Industry. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2018, 22, 420–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedi, H.S.; Yadav, N. Social Entrepreneurship: A Conceptual Clarity 2019. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3541919 (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Urbano, D.; Toledano, N.; Soriano, D.R. Analyzing Social Entrepreneurship from an Institutional Perspective: Evidence from Spain. J. Soc. Entrep. 2010, 1, 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dees, J.G.; Emerson, J.; Economy, P. Strategic Tools for Social Entrepreneurs: Enhancing the Performance of Your Enterprising Nonprofit; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Mamabolo, A. Performance Measurement in Emerging Market Social Enterprises Using a Balanced Scorecard. J. Soc. Entrep. 2020, 11, 65–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newbert, S.L.; Hill, R.P. Setting the Stage for Paradigm Development: A ‘Small-Tent’ Approach to Social Entrepreneurship. J. Soc. Entrep. 2014, 5, 243–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahfuz Ashraf, M.; Razzaque, M.A.; Liaw, S.-T.; Ray, P.K.; Hasan, M.R. Social Business as an Entrepreneurship Model in Emerging Economy: Systematic Review and Case Study. Manag. Decis. 2018, 57, 1145–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacq, S.; Janssen, F. The Multiple Faces of Social Entrepreneurship: A Review of Definitional Issues Based on Geographical and Thematic Criteria. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2011, 23, 373–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, W.; Lee, H.; Ghobadian, A.; O’Regan, N.; James, P. Social Innovation and Social Entrepreneurship: A Systematic Review. Group Organ. Manag. 2015, 40, 428–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawhouser, H.; Cummings, M.; Newbert, S.L. Social Impact Measurement: Current Approaches and Future Directions for Social Entrepreneurship Research. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2019, 43, 82–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Modoi, O.-C.; Vescan, A. Environmental Protection and Social Entrepreneurship Activities: The Vision of the Young People. Environ. Sci. Proc. 2021, 9, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, E.; Yoo, H. A Systematic Literature Review of Women in Social Entrepreneurship. Serv. Bus. 2022, 16, 935–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherrier, H.; Goswami, P.; Ray, S. Social Entrepreneurship: Creating Value in the Context of Institutional Complexity. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 86, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A.; Gedajlovic, E.; Neubaum, D.O.; Shulman, J.M. A Typology of Social Entrepreneurs: Motives, Search Processes and Ethical Challenges. J. Bus. Ventur. 2009, 24, 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saebi, T.; Foss, N.J.; Linder, S. Social Entrepreneurship Research: Past Achievements and Future Promises. J. Manag. 2019, 45, 70–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, J.; Noboa, E. Social Entrepreneurship: How Intentions to Create a Social Venture Are Formed. In Social Entrepreneurship; Mair, J., Robinson, J., Hockerts, K., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan UK: London, UK, 2006; pp. 121–135. ISBN 978-0-230-62565-5. [Google Scholar]

- Millman, C.; Li, Z.; Matlay, H.; Wong, W. Entrepreneurship Education and Students’ Internet Entrepreneurship Intentions: Evidence from Chinese HEIs. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2010, 17, 569–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peredo, A.M.; McLean, M. Social Entrepreneurship: A Critical Review of the Concept. J. World Bus. 2006, 41, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, S.; Sen, A. The Income Component of the Human Development Index. J. Hum. Dev. 2000, 1, 83–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.; Stern, S.; Green, M. Social Progress Imperative. Available online: https://www.socialprogress.org/ (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Phillips, R.; Holden, M.; Kee, Y.; Michalos, A.; Rahtz, D.; Joseph, S. Community Quality-of-Life and Well-Being; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo-Vergara, M.; Alvarez-Marin, A.; Placencio-Hidalgo, D. A Bibliometric Analysis of Creativity in the Field of Business Economics. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 85, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, X.Y.; Sun, J.; Bai, B. Bibliometrics of Social Media Research: A Co-Citation and Co-Word Analysis. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 66, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-W.; Huang, M.-H.; Lin, C.-W. Evolution of Research Subjects in Library and Information Science Based on Keyword, Bibliographical Coupling, and Co-Citation Analyses. Scientometrics 2015, 105, 2071–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan Tan, L. Bibliometrics of Social Entrepreneurship Research: Cocitation and Bibliographic Coupling Analyses. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2022, 9, 2124594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey-Martí, A.; Ribeiro-Soriano, D.; Palacios-Marqués, D. A Bibliometric Analysis of Social Entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1651–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao-Nicholson, R.; Vorley, T.; Khan, Z. Social Innovation in Emerging Economies: A National Systems of Innovation Based Approach. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2017, 121, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vázquez-Parra, J.C.; Cruz-Sandoval, M.; Carlos-Arroyo, M. Social Entrepreneurship and Complex Thinking: A Bibliometric Study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granados, M.L.; Hlupic, V.; Coakes, E.; Mohamed, S. Social Enterprise and Social Entrepreneurship Research and Theory: A Bibliometric Analysis from 1991 to 2010. Soc. Enterp. J. 2011, 7, 198–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dettori, A.; Floris, M. Technology in Social Entrepreneurship Studies: A Bibliometric Analysis (1990-2019). Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2021, 16, p41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco-Muñoz, J.F.; Aznar-Sánchez, J.A.; Belmonte-Ureña, L.J.; Román-Sánchez, I.M. Sustainable Water Use in Agriculture: A Review of Worldwide Research. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aydin, C.; Senel, E. Impotence Literature: Scientometric Analysis of Erectile Dysfunction Articles between 1975 and 2018. Andrologia 2020, 52, e13520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broadus, R.N. Toward a Definition of “Bibliometrics”. Scientometrics 1987, 12, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, M.; Oppenheim, C. Comparing Alternatives to the Web of Science for Coverage of the Social Sciences’ Literature. J. Informetr. 2007, 1, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comerio, N.; Strozzi, F. Tourism and Its Economic Impact: A Literature Review Using Bibliometric Tools. Tour. Econ. 2019, 25, 109–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zupic, I.; Čater, T. Bibliometric Methods in Management and Organization. Organ. Res. Methods 2015, 18, 429–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkerhoff, D.W.; Brinkerhoff, J.M. Public–Private Partnerships: Perspectives on Purposes, Publicness, and Good Governance. Public Adm. Dev. 2011, 31, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.B.; Dana, L.P.; Dana, T.E. Indigenous Land Rights, Entrepreneurship, and Economic Development in Canada: “Opting-in” to the Global Economy. J. World Bus. 2006, 41, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bradley, S.W.; McMullen, J.S.; Artz, K.; Simiyu, E.M. Capital Is Not Enough: Innovation in Developing Economies. J. Manag. Stud. 2012, 49, 684–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrini, F.; Vurro, C.; Costanzo, L.A. A Process-Based View of Social Entrepreneurship: From Opportunity Identification to Scaling-up Social Change in the Case of San Patrignano. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2010, 22, 515–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.; Syrett, S. Generating Social Capital?: The Social Economy and Local Economic Development. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2007, 14, 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hayhurst, L.M.C. The ‘Girl Effect’ and Martial Arts: Social Entrepreneurship and Sport, Gender and Development in Uganda. Gend. Place Cult. 2014, 21, 297–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surie, G. Creating the Innovation Ecosystem for Renewable Energy via Social Entrepreneurship: Insights from India. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2017, 121, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ebrashi, R. Social Entrepreneurship Theory and Sustainable Social Impact. Soc. Responsib. J. 2013, 9, 188–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, A.; Teasdale, S. Unlocking the Potential of Rural Social Enterprise. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 70, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, R. Rural Social Enterprises as Embedded Intermediaries: The Innovative Power of Connecting Rural Communities with Supra-Regional Networks. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 70, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, M.; Healy, K.; Crofts, P. Social Enterprise: Is It the Business of Social Work? Aust. Soc. Work 2003, 56, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meyskens, M.; Carsrud, A.L.; Cardozo, R.N. The Symbiosis of Entities in the Social Engagement Network: The Role of Social Ventures. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2010, 22, 425–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosca, E.; Agarwal, N.; Brem, A. Women Entrepreneurs as Agents of Change: A Comparative Analysis of Social Entrepreneurship Processes in Emerging Markets. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 157, 120067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, F.; Fayolle, A.; Wuilaume, A. Researching Bricolage in Social Entrepreneurship. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2018, 30, 450–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, V.J.; Desivilya, H. Integrating Social Entrepreneurship and Conflict Engagement for Regional Development in Divided Societies. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2010, 22, 495–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roundy, P.T. Social Entrepreneurship and Entrepreneurial Ecosystems: Complementary or Disjoint Phenomena? Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2017, 44, 1252–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nega, B.; Schneider, G. Social Entrepreneurship, Microfinance, and Economic Development in Africa. J. Econ. Issues 2014, 48, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, S.-A. Towards a Geographical Research Agenda for Social Enterprise. Area 2010, 42, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canestrino, R.; Ćwiklicki, M.; Magliocca, P.; Pawełek, B. Understanding Social Entrepreneurship: A Cultural Perspective in Business Research. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 110, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddulph, R. Social Enterprise and Inclusive Tourism. Five Cases in Siem Reap, Cambodia. Tour. Geogr. 2018, 20, 610–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kedmenec, I.; Strašek, S. Are Some Cultures More Favourable for Social Entrepreneurship than Others? Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraživanja 2017, 30, 1461–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nicolás, C.; Rubio, A. Social Enterprise: Gender Gap and Economic Development. Eur. J. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2016, 25, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kadol, N. The process of formation and directions of social entrepreneurship development in the countries of the Eurasian Economic Union. Int. J. Entrepreneurship 2020, 24, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Doherty, B.; Haugh, H.; Lyon, F. Social Enterprises as Hybrid Organizations: A Review and Research Agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2014, 16, 417–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pache, A.-C.; Santos, F. Inside the Hybrid Organization: Selective Coupling as a Response to Competing Institutional Logics. Acad. Manage. J. 2013, 56, 972–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tracey, P.; Phillips, N.; Jarvis, O. Bridging Institutional Entrepreneurship and the Creation of New Organizational Forms: A Multilevel Model. Organ. Sci. 2011, 22, 60–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Sarachaga, J.M.; Ariza-Montes, A. The Role of Social Entrepreneurship in the Attainment of the Sustainable Development Goals. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 152, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Reji, E.M. Social Entrepreneurship and Sustainable Development. Available online: https://www.routledge.com/Social-Entrepreneurship-and-Sustainable-Development/Singh-Reji/p/book/9780367501761 (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- Kaswan, M.S.; Rathi, R.; Cross, J.; Garza-Reyes, J.A.; Antony, J.; Yadav, V. Integrating Green Lean Six Sigma and Industry 4.0: A Conceptual Framework. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2022, 34, 87–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathi, R.; Kaswan, M.S.; Antony, J.; Cross, J.; Garza-Reyes, J.A.; Furterer, S.L. Success Factors for the Adoption of Green Lean Six Sigma in Healthcare Facility: An ISM-MICMAC Study. Int. J. Lean Six Sigma 2022. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, V.; Gahlot, P.; Kaswan, M.S.; Rathi, R. Green Lean Six Sigma Critical Barriers: Exploration and Investigation for Improved Sustainable Performance. Int. J. Six Sigma Compet. Advant. 2021, 13, 101–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, J.; Martí, I. Social Entrepreneurship Research: A Source of Explanation, Prediction, and Delight. J. World Bus. 2006, 41, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Depiction | Outcomes |

|---|---|

| Duration | 1996:2022 |

| Sources (Journals, Books, etc.) | 207 |

| Articles | 300 |

| Annual Rate of Growth (%) | 5.27 |

| Mean Age of Article | 6.08 |

| Mean Citations Per Article | 13.79 |

| References | 15,249 |

| Keywords Plus | 482 |

| Author’s Keywords | 785 |

| Authors | 673 |

| Authors of Single-authored Article | 87 |

| Single-authored Article | 94 |

| Co-authors Per Article | 2.38 |

| International Co-authorship (%) | 15.67 |

| Countries | 69 |

| Organizations | 496 |

| Element | H-Index | G-Index | M-Index | TC | NP | PY_Start |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurship and Regional Development | 8 | 9 | 0.571 | 436 | 9 | 2010 |

| Sustainability Switzerland | 7 | 11 | 1.167 | 143 | 12 | 2018 |

| Voluntas | 6 | 7 | 0.667 | 77 | 7 | 2015 |

| International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business | 4 | 4 | 0.400 | 52 | 4 | 2014 |

| International Journal of Social Economics | 4 | 4 | 0.222 | 99 | 4 | 2006 |

| Journal of Rural Studies | 4 | 4 | 0.800 | 198 | 4 | 2019 |

| Local Economy | 4 | 4 | 0.364 | 33 | 4 | 2013 |

| Technological Forecasting and Social Change | 4 | 5 | 0.444 | 270 | 5 | 2015 |

| Frontiers in Psychology | 3 | 3 | 0.750 | 77 | 3 | 2020 |

| Journal of Business Ethics | 3 | 3 | 0.214 | 121 | 3 | 2010 |

| Authors | Articles | Articles Fractionalized |

|---|---|---|

| Kadol, N. | 5 | 4.00 |

| Ferguson, K.M. | 4 | 2.75 |

| Luke, B. | 3 | 1.00 |

| Ahmad, S. | 2 | 1.50 |

| Barraket, J. | 2 | 0.50 |

| Barth, S. | 2 | 0.50 |

| Crofts, P. | 2 | 0.83 |

| Dogar, M.N. | 2 | 2.00 |

| Grigorieva, V.V. | 2 | 0.7 |

| Healy, K. | 2 | 1.33 |

| Authors | H-Index | G-Index | M-Index | TC | NP | PY_Start |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ferguson, K.M. | 4 | 4 | 0.235 | 77 | 4 | 2007 |

| Luke, B. | 3 | 3 | 0.167 | 69 | 3 | 2007 |

| Barraket, J. | 2 | 2 | 0.222 | 59 | 2 | 2015 |

| Barth, S. | 2 | 2 | 0.222 | 59 | 2 | 2015 |

| Healy, K. | 2 | 2 | 0.071 | 80 | 2 | 1996 |

| Legrand, W. | 2 | 2 | 0.182 | 39 | 2 | 2013 |

| Manimala, M.J. | 2 | 2 | 0.154 | 10 | 2 | 2011 |

| Nega, B. | 2 | 2 | 0.200 | 53 | 2 | 2014 |

| Pennink, B.J.W. | 2 | 2 | 0.200 | 12 | 2 | 2014 |

| Schneider, G. | 2 | 2 | 0.200 | 53 | 2 | 2014 |

| Articles Written | Number of Authors | Ratio of Authors |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 639 | 0.949 |

| 2 | 31 | 0.046 |

| 3 | 1 | 0.001 |

| 4 | 1 | 0.001 |

| 5 | 1 | 0.001 |

| Country | Aggregate Citations | Mean Article Citations |

|---|---|---|

| USA | 979 | 35.00 |

| Canada | 436 | 29.10 |

| UK | 400 | 28.60 |

| Italy | 294 | 32.70 |

| Australia | 166 | 15.10 |

| China | 144 | 13.10 |

| Spain | 102 | 17.00 |

| Croatia | 83 | 20.80 |

| Egypt | 83 | 83.00 |

| Germany | 75 | 25.00 |

| Paper | DOI | Total Citations | TC per Year | Normalized TC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRINKERHOFF DW, 2011, PUBLIC ADM DEV [48] | 10.1002/pad.584 | 306 | 23.54 | 2.93 |

| ANDERSON RB, 2006, J WORLD BUS [49] | 10.1016/j.jwb.2005.10.005 | 209 | 11.61 | 4.11 |

| BRADLEY SW, 2012, J MANAGE STUD [50] | 10.1111/j.1467-6486.2012. 01043.x | 199 | 16.58 | 6.77 |

| PERRINI F, 2010, ENTREP REG DEV [51] | 10.1080/08985626.2010.488402 | 171 | 12.21 | 3.53 |

| EVANS M, 2007, EUR URBAN REG STUD [52] | 10.1177/0969776407072664 | 106 | 6.24 | 2.42 |

| HAYHURST LMC, 2014, GENDER PLACE CULT [53] | 10.1080/0966369X.2013.802674 | 97 | 9.70 | 6.37 |

| RAO-NICHOLSON R, 2017, TECHNOL FORECAST SOC CHANGE [38] | 10.1016/j.techfore.2017.03.013 | 90 | 12.86 | 4.49 |

| SURIE G, 2017, TECHNOL FORECAST SOC CHANGE [54] | 10.1016/j.techfore.2017.03.006 | 85 | 12.14 | 4.24 |

| EBRASHI RE, 2013, SOC RESPONSIB J [55] | 10.1108/SRJ-07-2011-0013 | 83 | 7.55 | 6.30 |

| STEINER A, 2019, J RURAL STUD [56] | 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2017.12.021 | 78 | 15.60 | 6.32 |

| RICHTER R, 2019, J RURAL STUD [57] | 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2017.12.005 | 77 | 15.40 | 6.24 |

| GRAY M, 2003, AUST SOC WORK [58] | 10.1046/j.0312-407X.2003. 00060.x | 77 | 3.67 | 1.00 |

| MEYSKENS M, 2010, ENTREP REG DEV [59] | 10.1080/08985620903168299 | 65 | 4.64 | 1.34 |

| ROSCA E, 2020, TECHNOL FORECAST SOC CHANGE [60] | 10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120067 | 64 | 16.00 | 7.66 |

| JANSSEN F, 2018, ENTREP REG DEV [61] | 10.1080/08985626.2017.1413769 | 64 | 10.67 | 5.55 |

| Document | DOI | Year | Local Citations | Global Citations | LC/GC Ratio (%) | Normalized Local Citations | Normalized Global Citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EBRASHI RE, 2013, SOC RESPONSIB J [55] | 10.1108/SRJ-07-2011-0013 | 2013 | 5 | 83 | 6.02 | 9.17 | 6.30 |

| FRIEDMAN VJ, 2010, ENTREP REG DEV [62] | 10.1080/08985626.2010.488400 | 2010 | 4 | 53 | 7.55 | 3.00 | 1.09 |

| GRAY M, 2003, AUST SOC WORK [58] | 10.1046/j.0312-407X.2003. 00060.x | 2003 | 4 | 77 | 5.19 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| ROUNDY PT, 2017, INT J SOC ECON [63] | 10.1108/IJSE-02-2016-0045 | 2017 | 3 | 62 | 4.84 | 6.90 | 3.09 |

| NEGA B, 2014, J ECON ISSUES [64] | 10.2753/JEI0021-3624480210 | 2014 | 3 | 32 | 9.38 | 9.86 | 2.10 |

| PERRINI F, 2010, ENTREP REG DEV [51] | 10.1080/08985626.2010.488402 | 2010 | 3 | 171 | 1.75 | 2.25 | 3.53 |

| MUÑOZ S-A, 2010, AREA [65] | 10.1111/j.1475-4762.2009. 00926.x | 2010 | 3 | 52 | 5.77 | 2.25 | 1.07 |

| CANESTRINO R, 2020, J BUS RES [66] | 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.01.006 | 2020 | 2 | 50 | 4.00 | 13.33 | 5.99 |

| BIDDULPH R, 2018, TOUR GEOGR [67] | 10.1080/14616688.2017.1417471 | 2018 | 2 | 16 | 12.50 | 10.57 | 1.39 |

| JANSSEN F, 2018, ENTREP REG DEV [61] | 10.1080/08985626.2017.1413769 | 2018 | 2 | 64 | 3.13 | 10.57 | 5.55 |

| KEDMENEC I, 2017, ECONOMIC RES EKON ISTRAZ [68] | 10.1080/1331677X.2017.1355251 | 2017 | 2 | 59 | 3.39 | 4.60 | 2.94 |

| SURIE G, 2017, TECHNOL FORECAST SOC CHANGE [54] | 10.1016/j.techfore.2017.03.006 | 2017 | 2 | 85 | 2.35 | 4.60 | 4.24 |

| NICOLÁS C, 2016, EUROPEAN J MANAG BUS ECONOM [69] | 10.1016/j.redeen.2015.11.001 | 2016 | 2 | 26 | 7.69 | 12.67 | 2.76 |

| BRADLEY SW, 2012, J MANAGE STUD [50] | 10.1111/j.1467-6486.2012. 01043.x | 2012 | 2 | 199 | 1.01 | 6.67 | 6.77 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Satar, M.S.; Aggarwal, D.; Bansal, R.; Alarifi, G. Mapping the Knowledge Structure and Unveiling the Research Trends in Social Entrepreneurship and Inclusive Development: A Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5626. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15075626

Satar MS, Aggarwal D, Bansal R, Alarifi G. Mapping the Knowledge Structure and Unveiling the Research Trends in Social Entrepreneurship and Inclusive Development: A Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability. 2023; 15(7):5626. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15075626

Chicago/Turabian StyleSatar, Mir Shahid, Deepanshi Aggarwal, Rohit Bansal, and Ghadah Alarifi. 2023. "Mapping the Knowledge Structure and Unveiling the Research Trends in Social Entrepreneurship and Inclusive Development: A Bibliometric Analysis" Sustainability 15, no. 7: 5626. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15075626