Abstract

The Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami struck the northeastern coastal area of Japan on 11 March 2011, resulting in the relocation of 329,000 households and the repair of 572,000 houses. Previous studies predominantly addressed the impact of demographic factors on housing recovery. However, the types of housing recoveries and the impact of individual psycho-behavioral factors have been poorly addressed. This study examined the impact of survivors’ demographic and personality-trait factors using a discriminant analysis of five types of housing recovery among 573 survivors in the five years after the disaster. The results revealed two important axes. One axis discriminated self-procured (rebuilt, repaired, and chartered housing) houses from those that were publicly available (emergency temporary and public disaster housing) affected by three personality traits (stubbornness, problem-solving, and active well-being) and survivors’ age. The other axis represented rebuilt houses affected by household size. These results demonstrate that personality traits and not just demographic factors impact three types of self-procured housing recoveries. Further exploration of personality traits that impact housing recovery can improve post-disaster reconstruction and recovery practices.

1. Introduction

Various factors determine the speed of recovery and quality of life after massive disasters. One such important factor is housing recovery. It is known that housing damage caused delays in the subjective sense of recovery [1,2] and prolonged lower levels of subjective well-being [3] in victims of the 1995 Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake. Other factors include political, institutional, and economic conditions, the sociocultural capital of communities, and the demographic characteristics of households and individuals [4,5,6,7,8,9]. Interestingly, the personality traits of the victims also influence disaster recovery [10,11,12,13]. Understanding the impact of such psycho-behavioral factors may help improve disaster resilience [13,14,15,16]. Previous studies discussed their impact in relation to the 2013 flood in Germany [17], the 2010 Chile earthquake [18], and the disasters that occurred in Oceania between 1983 and 2013 [19]. In this study, we investigated the relationship between the personality traits of disaster survivors and housing recovery in the five years after the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami.

The Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami struck northeastern coastal areas of Japan on 11 March 2011, severely damaging the Miyagi, Iwate, and Fukushima prefectures. Approximately 18,500 people died or went missing, and over 390,000 houses were destroyed [20]. Furthermore, 329,000 households were relocated, and 572,000 houses required repair [21]. In this disaster, the economic status of survivors did not necessarily play a major role in housing recovery [22]. Upon surveying disaster survivors about housing recovery after this disaster, it was found that older adults [23,24,25] and small households [25,26] reconstructed their houses after a long time. However, few studies have investigated whether the personality traits of disaster victims influenced housing recovery after the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami. Therefore, studies must address demographic as well as psycho-behavioral factors, such as the personality traits of disaster survivors.

Recently, Sato et al. [12] examined personality traits and demographic factors that promoted survivors’ life recovery after the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami. They conducted a postal survey of 3600 people who lived in the tsunami-affected areas in Miyagi prefecture in December 2013. They measured personality traits using the eight characteristics associated with the “power to live” (with disasters), which have been demonstrated to be advantageous for survival in various disaster-related contexts [16,27,28,29,30]. Those eight traits are leadership (for example, “To resolve problems, I gather together everyone involved to discuss the matter.”), problem-solving (for example, “When I am fretting about what I should do, I compare several alternative actions.”), altruism (for example, “When I see someone having trouble, I have to help them.”), stubbornness (for example, “I am stubborn and always get my own way.”), etiquette (for example, “On a daily basis, I take the initiative in greetings family members and people living in the neighborhood.”), emotional regulation (for example, “During difficult times, I endeavor not to brood.”), self-transcendence (for example, “I am aware that I am alive, have a sense of responsibility in living.”), and active well-being (for example, “In everyday life, I have habitual practices that are essential for relieving stress or giving me a change of pace.”) [27,29]. The results showed that leadership, problem-solving, emotional regulation, self-transcendence, and active well-being traits were relevant to the housing recovery of the survivors. However, the researchers [12] did not consider different types of housing recovery.

There were various forms of housing recovery after the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami. Emergency temporary housing, public disaster housing, and private chartered housing were provided by municipalities to individuals who chose not to engage in housing recovery. Emergency temporary housing and public disaster housing differed in terms of the living environment and the duration/tenure of the tenant’s occupancy and thus were distinct from one another. Private chartered housing was different from emergency temporary housing and public disaster housing because individuals had to look for such properties themselves [31]. Repaired and reconstructed housing were houses occupied by individuals who chose to engage in housing recovery. However, their costs may vary considerably. In addition, the impact of personality traits on survivors’ housing recovery may differ because their housing recovery continued after 2013. For instance, active well-being may be related to housing recovery because it has been found that survivors whose mental or physical health was at risk engaged in limited housing recovery [25,26]. Similarly, problem-solving and stubbornness may be associated with recovering housing after some time has passed because of the importance of survivors’ decisiveness and willpower in recovering their house [32].

In this study, we further investigated the impact of personality traits, along with demographic factors such as age and household size, on survivors’ housing recovery after the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami. More specifically, we examined the relationship between demographic and personality factors and the types of housing recovery. We analyzed data from 2016. This was an optimal time to explore the determinants of housing recovery because five years had passed since the disaster, and the number of occupied emergency housing units had been reduced by half [33].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

We used the survey data of 3470 individuals (2036 male participants, 1428 female participants, and 6 unknown) pertaining to January and February 2016 collected by the Tohoku University International Research Institute of Disaster Science and the Kahoku Shimpo Publishing Co., Ltd. (Sendai, Japan) The surveys targeted the survivors of the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami. A survey questionnaire was mailed to 373 individuals living in Miyagi Prefecture who had provided written informed consent to be included in follow-up surveys related to the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami. Among these, a total of 188 responses were received. The same questionnaire was distributed by the Kahoku Shimpo Publishing Co., Ltd. to 1200 randomly selected individuals living in temporary/public disaster housing in six municipalities (Minamisanriku, Onagawa, Yamamoto, Higashimatsushima, Shichigahama, and Watari) in the Miyagi Prefecture; 284 responses were obtained. Finally, an Internet survey using the same questionnaire items was conducted by the Survey Research Center Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan) by drawing panel respondents from the coastal municipalities of Miyagi Prefecture, and 2998 responses were obtained.

2.2. Data Analysis

We analyzed respondents’ data on housing recovery type, age, household size, and the Power to Live with Disasters (hereafter, power to live) scale. Participants were asked to report their age and indicate household size in terms of the number of people in the same household, including themselves. They were to choose from the following alternatives to indicate their housing situation at the time of the survey: Emergency temporary housing, public disaster housing, private chartered housing, repaired housing (repaired their house that was damaged during the disaster), reconstructed housing (lost their house to the disaster and rebuilt one), their own home (undamaged by the disaster), and other.

The Power to Live scale includes eight factors: Leadership, problem-solving, altruism, stubbornness, etiquette, emotional regulation, self-transcendence, and active well-being. The questionnaire comprised 34 items describing ways of thinking, daily attitudes, and habits, and each factor had three to five items [27]. Previous studies demonstrate the beneficial impact of several of these personality traits on avoiding danger and overcoming adversities during tsunami evacuation and reconstruction work [16,27,28]. They have also been found to promote mutually beneficial behaviors, such as helping others during an evacuation [29]. The internal consistency and concurrent validity of the questionnaire have been established [28,30]. Participants responded on a 6-point Likert scale (0 = not at all, 5 = very much). For each of the power-to-live factor scale scores, the item scores were summed and converted into a percentage of the total score.

We examined housing recovery based on a discriminant analysis of the housing types in response to the multitude of factors involved. This approach was used to consider the vastly different costs associated with repairing an existing dwelling and reconstructing a new one since we consider both as housing recovery types.

3. Results

Responses from 1984 individuals (1253 men and 731 women) were obtained after excluding responses that had insufficient or missing data on housing recovery type, age, household size, and the score of each of the power-to-live scale factors. The following responses were obtained from the three surveys for each housing recovery type: Mail survey (n = 108; emergency temporary housing = 48, public disaster housing = 17, reconstructed housing = 37, and repaired housing = 6), Internet survey (n = 1729; emergency temporary housing = 12, public disaster housing = 19, reconstructed housing = 51, repaired housing = 198, private chartered housing = 38, own home = 1000, and private chartered housing = 411), and posting survey (n = 147; emergency temporary housing = 93, public disaster housing = 37, reconstructed housing = 15, private chartered housing = 1, and repaired housing = 1). Responses obtained from individuals living in their “own homes” (n = 1000) were from those whose homes remained undamaged by the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami, making repair and/or reconstruction unnecessary. People living in private chartered housing (n = 411) were not responsible for rebuilding their homes. We analyzed the responses of those individuals who had the opportunity to engage in housing recovery (n = 573 (334 men and 239 women), emergency temporary housing = 153 (78 men and 75 women), private chartered housing = 39 (24 men and 15 women), public disaster housing = 73 (30 men and 43 women), reconstructed housing = 103 (63 men and 40 women), and repaired housing = 205 (139 men and 66 women)).

Table 1 presents the mean values of survivors’ age, household size, and the score of each of the power-to-live scale factors according to the type of housing recovery. A multivariate analysis of variance was used to investigate the differences in age, household size, and the score of each of the power-to-live scale factors. The housing recovery types (five levels: Emergency temporary housing, private chartered housing, public disaster housing, reconstructed housing, and repaired housing) were the independent variables, and age, household size, and each of the power-to-live scale factors were the dependent variables. Resultingly, the main effect of housing recovery type was significant (F (40, 2248) = 5.19, p < 0.001). Additionally, significant main effects were observed for age (F (4, 568) = 18.60, p < 0.001) and household size (F (4, 568) = 16.92, p < 0.001). Significant main effects were also observed for all subscales on the power to live scale except for the scale of etiquette (Leadership: F (4, 568) = 4.36, p < 0.01; Problem-solving: F (4, 568) = 11.14, p < 0.001; Altruism: F (4, 568) = 5.91, p < 0.001; Stubbornness: F (4, 568) = 14.05, p < 0.001; Emotion regulation: F (4, 568) = 4.08, p < 0.01; Self-transcendence (4, 568): F = 2.86, p < 0.05; Active well-being: F (4, 568) = 7.79, p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Mean and standard deviation (M ± SD) of age, household size (number of people in the same household), and score of each of the power-to-live scale factors for each type of housing.

As there were significant differences in these variables based on the type of housing recovery, we performed a canonical discriminant analysis with age, household size, and the score of each of the power-to-live scale factors as independent variables. Two canonical discrimination functions were found to be significant at the 5% threshold (Table 2).

Table 2.

Results of canonical discriminant analysis.

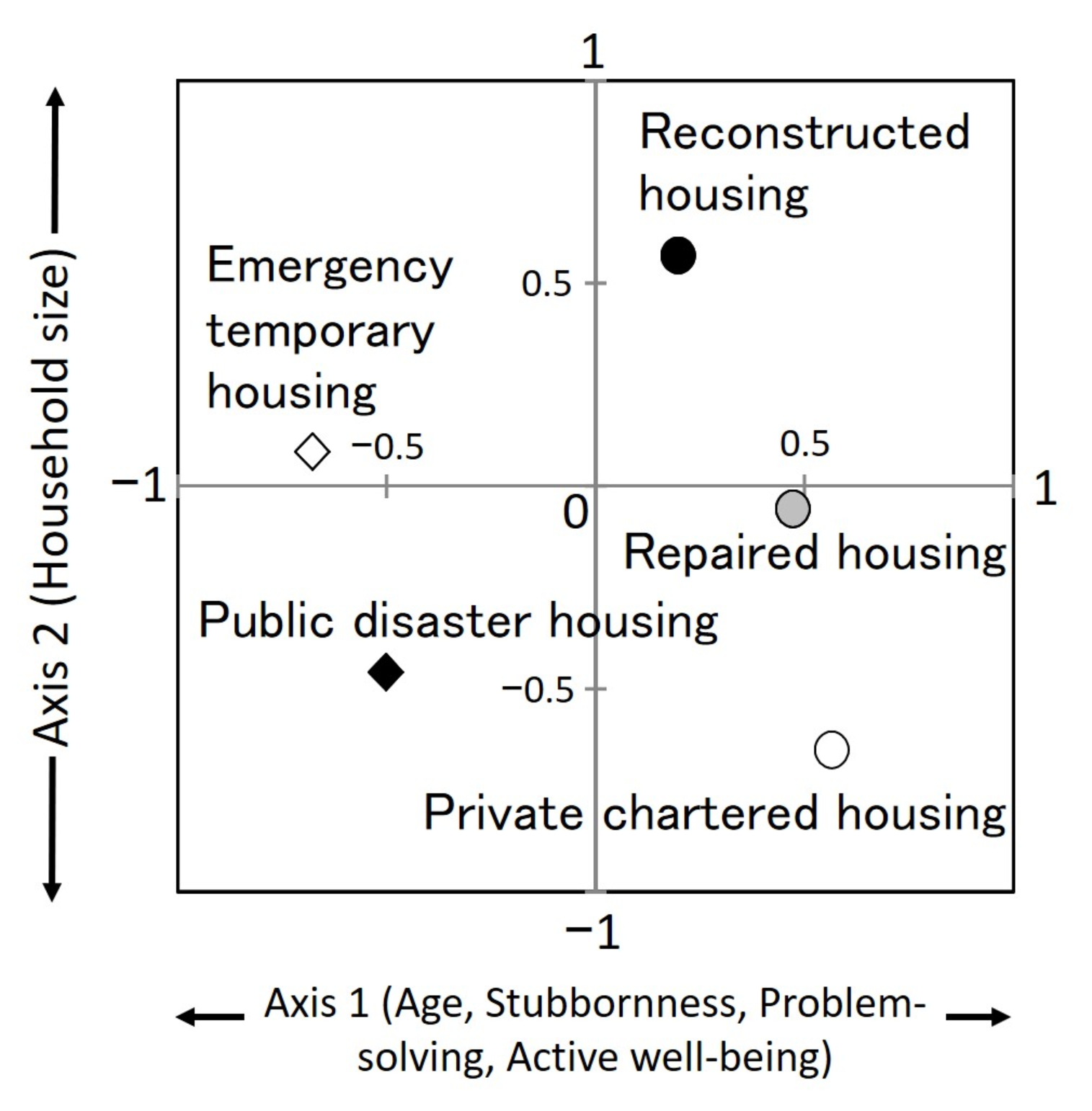

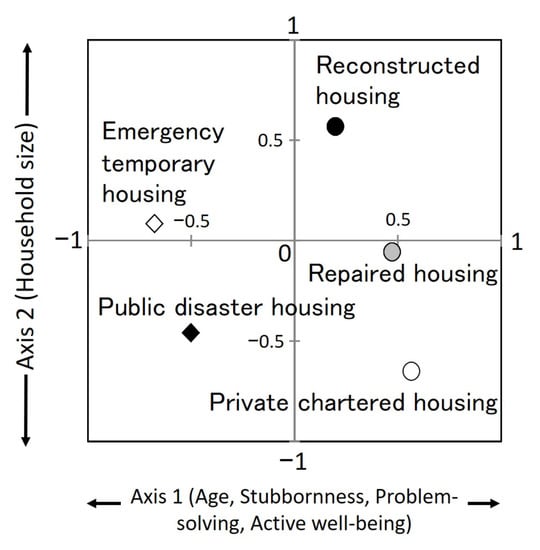

The first canonical discrimination function (Axis 1) accounted for 65.2% of the total variance (Wilk’s λ = 0.69, χ2 = 208.96, df = 40, p < 0.001). Age and the stubbornness, problem-solving, and active well-being subscales of the power-to-live scale contributed largely to Axis 1. Meanwhile, the second canonical discrimination function (Axis 2) accounted for 28.8% of the total variance (Wilk’s λ = 0.87, χ2 = 76.14, df = 27, p < 0.001). Household size contributed significantly to Axis 2. Axes 1 and 2 were set as the X- and Y-axis, respectively, and we created a plot separating emergency temporary housing, private chartered housing, public disaster housing, reconstructed housing, and repaired housing based on their canonical discrimination function values (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Separation of housing recovery types along Axes 1 and 2. The circles represent three types of self-procured housing. The black circle indicates reconstructed housing, the gray circle indicates repaired housing, and the white circle indicates private chartered housing. In contrast, the rhombuses represent two types of publicly available housing. The black rhombus represents public disaster housing, and the white rhombus represents emergency temporary housing.

The positive direction on Axis 1 (x-axis) signifies young age, high stubbornness, high problem-solving, and high active well-being. The positive direction on Axis 2 (y-axis) indicates a large household size. Individuals in emergency temporary housing (X = −0.68, Y = 0.08) were reported to be older adults and have low stubbornness, problem-solving ability, and active well-being. By contrast, individuals in private chartered housing (X = 0.57, Y = −0.65) and repaired housing (X = 0.47, Y = −0.06) were younger and showed high stubbornness, problem-solving ability, and active well-being. Individuals in private chartered housing also had small households. However, individuals in reconstructed housing (X = 0.20, Y = 0.57) reported large households. Finally, individuals in public disaster housing (X = −0.50, Y = −0.46) were reported to be older adults, have low stubbornness, problem-solving ability, and active well-being, and live in small households.

4. Discussion

This study identified two axes based on the discriminant analysis of the types of housing recovery. Reconstructed, repaired, and private chartered housing, that is, self-procured housing, were discriminated from emergency temporary housing and public disaster housing on Axis 1, which reflected age, stubbornness, problem-solving, and active well-being. Axis 2 reflected household size; it had reconstructed housing on its positive side and private chartered housing and public disaster housing on its negative side. Therefore, in addition to younger age, high stubbornness, high problem-solving, and high active well-being (three personality traits) positively impacted an individual’s ability to secure housing for themselves and their families. Independent of these factors, a large household size contributed to individuals’ decision to pursue housing recovery.

The findings of this study indicate the impact of stubbornness, problem-solving, and active well-being on self-procured housing recovery in the five years after the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami. The impacts of problem-solving and active well-being were consistent with a previous study in which the impact of personality traits on housing recovery was examined without consideration of the different types of housing recovery [12]. Stubbornness represents the personality trait, attitude, or habit of sticking to one’s desires or beliefs [27,29]. Honda et al. [34] reported that stubbornness is associated with other personality traits related to achieving long-term goals, such as grit [35,36,37,38,39] and self-control [40,41,42,43,44]. Matsukawa et al. [24] pointed out that strong social capital and the resulting peer pressure in emergency temporary housing may inhibit survivors from engaging in housing recovery. Meanwhile, in neuroscience, it has been demonstrated that stubborn individuals are not highly concerned about others’ opinions [45]. Thus, stubbornness may have positively affected housing recovery by providing resistance to this peer pressure. Problem-solving refers to the attitude or habit of strategically tackling problems [27,29]. It has been proven to be advantageous during all phases of a disaster [16,27,28,29,30]. Its association with the efficiency of response strategies has also been demonstrated at the neural level [46]. Shigekawa et al. [31] reported that survivors who began to act immediately after a disaster and those who proactively sought information from their friends and acquaintances were able to secure private chartered housing. Therefore, our finding that the problem-solving trait influences self-procured housing recovery is consistent with the findings of previous studies [12,31,46]. Active well-being refers to the daily practice of maintaining or improving one’s physical, mental, and intellectual status [27,29]. Previous studies suggest [23,25] that it is related to survivors’ health status and housing recovery, aligning with our finding that active well-being is associated with housing recovery.

This study demonstrates that demographic factors and personality traits influenced three types of self-procured housing recoveries in the five years after the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami. Specifically, our results showed that self-procurement of houses (rebuilt, repaired, and chartered housing) from those that were publicly available (emergency temporary and public disaster housing) was affected by three personality traits (stubbornness, problem-solving, and active well-being) and survivors’ age. In the future, providing psychological support to older survivors that lack these three personality traits may help encourage housing recovery post-disasters. In particular, those with low levels of these personality traits are likely to have difficulty rebuilding their homes on their own. Therefore, practitioners should develop psychological interventions and social support to strengthen these personality traits. We also believe that further exploration of personality traits that influence housing recovery can contribute to improving post-disaster reconstruction and recovery practices because housing damage causes delays in the subjective sense of recovery [1,2] and prolonged lower levels of subjective well-being [3].

This study has a few limitations. It focuses on disaster survivors and does not gauge whether the eight personality traits are associated with housing recovery in normal circumstances. Furthermore, the generalizability of our findings to survivors of other disasters remains unclear. Responses from survivors in this study were obtained from residents in Miyagi Prefecture. Therefore, it is unclear whether the same results would be obtained in Iwate and Fukushima prefectures, which were affected areas by the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami [26,47,48]. Particularly in Fukushima prefecture, the results may differ from the present study, considering the public’s reaction to the Fukushima nuclear accident [49,50,51,52,53,54]. Finally, we believe that all participants responded honestly to the questionnaire, but there is no guarantee of this. Future research should address these limitations.

Author Contributions

All authors were involved in study design, data analysis, and data interpretation. A.H. performed writing—original draft preparation. S.S., M.S. and F.I. contributed to data acquisition. A.H. and M.S. were involved in writing and funding acquisition. A.H. and T.A. performed formal analysis and visualization. A.H. and M.S. contributed writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by a Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) (Grant Number: 17H06219), Tohoku University International Research Institute of Disaster Science Joint Research Project, Japan Science and Technology Agency, and Nankai Trough Wide Area Earthquake Disaster Prevention Project commissioned by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the International Research Institute of Disaster Sciences, Tohoku University (Protocol code: 2015-044).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all volunteers who participated in this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kimura, R.; Tomoyasu, K.; Yajima, Y.; Mashima, H.; Furukawa, K.; Toda, Y.; Watanabe, K.; Kawahara, T. Current status and issues of life recovery process three years after the Great East Japan earthquake questionnaire based on subjective estimate of victims using life recovery calendar method. J. Disaster Res. 2011, 9, 673–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, R.; Tamura, K.; Inoguchi, M.; Hayashi, H.; Tatsuki, S. Current situation and problems of the victims in the life recovery process of more than ten years: The survey on socio-economic recovery of sixteen years after the Great Hanshin-Awaji (Kobe) Earthquake Disaster. J. Soc. Saf. Sci. 2015, 27, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oishi, S.; Kimura, R.; Hayashi, H.; Tatsuki, S.; Tamura, K.; Ishii, K.; Tucker, J. Psychological adaptation to the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake of 1995: 16 years later victims still report lower levels of subjective well-being. J. Res. Personal. 2015, 55, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, D.P. The power of people: Social capital’s role in recovery from the 1995 Kobe earthquake. Nat. Hazards 2011, 56, 595–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, D.P. Building Resilience: Social Capital in Post-Disaster Recovery; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Aßheuer, T.; Thiele-Eich, I.; Braun, B. Coping with the impacts of severe flood events in Dhaka’s slums: The role of social capital. Erdkunde 2013, 67, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, F.H.; Stevens, S.P.; Pfefferbaum, B.; Wyche, K.F.; Pfefferbaum, R.L. Community resilience as a metaphor, theory, set of capacities, and strategy for disaster readiness. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2008, 41, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panday, S.; Rushton, S.; Karki, J.; Balen, J.; Barnes, A. The role of social capital in disaster resilience in remote communities after the 2015 Nepal earthquake. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduc. 2021, 55, 102112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaisie, E.; Han, S.S.; Kim, H.M. Complexity of resilience capacities: Household capitals and resilience outcomes on the disaster cycle in informal settlements. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduc. 2021, 60, 102292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, D.M.; Stehling-Ariza, T.; Park, Y.S.; Walsh, L.; Culp, D. Measuring individual disaster recovery: A socioecological framework. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2010, 4, S46–S54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golazad, S.; Heravi, G.; AminShokravi, A. People’s post-disaster decisions and their relations with personality traits and decision-making styles: The choice of travel mode and healthcare destination. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduc. 2022, 83, 103395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, S.; Ishibashi, R.; Sugiura, M. Two major elements of life recovery after a disaster: Their impacts dependent on housing damage and the contributions of psycho-behavioral factors. J. Disaster Res. 2021, 16, 1107–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, E.G.; Echols, E.T. Effects of optimism on recovery and mental health after a tornado outbreak. Psychol. Health 2017, 32, 530–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, H.; Wachtendorf, T.; Kendra, J.; Trainor, J. A snapshot of the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami: Societal impacts and consequences. Disaster Prev. Manag. 2006, 15, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rufat, S.; Tate, E.; Burton, C.G.; Maroof, A.S. Social vulnerability to floods: Review of case studies and implications for measurement. Int. J. Disaster Risk. 2015, 14, 470–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiura, M.; Ishibashi, R.; Abe, T.; Nouchi, R.; Honda, A.; Sato, S.; Muramoto, T.; Imamura, F. Self-help and mutual assistance in the aftermath of a tsunami: How individual factors contribute to resolving difficulties. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0258325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apel, D.; Coenen, M. Motivational and educational starting points to enhance mental and physical health in volunteer psycho-social support providers after the 2013 flood disaster in Germany. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduc. 2020, 43, e101359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maki, A.; Dwyer, P.C.; Blazek, S.; Snyder, M.; González, R.; Lay, S. Responding to natural disasters: Examining identity and prosociality in the context of a major earthquake. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2019, 58, 66–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaniasty, K.; de Terte, I.; Guilaran, J.; Bennett, S. A scoping review of post-disaster social support investigations conducted after disasters that struck the Australia and Oceania continent. Disasters 2020, 44, 336–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekiguchi, T.; Hagiwara, Y.; Sugawara, Y.; Tomata, Y.; Tanji, F.; Yabe, Y.; Itoi, E.; Tsuji, I. Moving from prefabricated temporary housing to public reconstruction housing and social isolation after the Great East Japan Earthquake: A longitudinal study using propensity score matching. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e026354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. Housing in Japan from the Viewpoint of Statistics (from the Results of ‘2013 Housing and Land Statistics Survey (Confirmed Report)’): Impact of Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami on Housing and Households. 2015. Available online: https://www.stat.go.jp/data/jyutaku/topics/topi862.html (accessed on 30 January 2023).

- Sato, S.; Matsukawa, A.; Tatsuki, S. Characteristics and problems of the 2011 Great East Japan earthquake and tsunami disaster survivors who are undecided on permanent housing plans: Natori city case study. J. JSNDS 2017, 36, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyagi Prefecture: Emergency Temporary Housing, etc. (Prefabricated/Private Rental Housing) Resident Health Survey Results. Available online: https://www.pref.miyagi.jp/soshiki/kensui/oukyuukasetsujyutaku.html (accessed on 30 January 2023).

- Matsukawa, A.; Sato, S.; Tatsuki, S. The study of the effects of choice of temporary housing to the housing recovery: Based on two years data of Natori city survey data 2014 and 2015. J. Soc. Saf. Sci. 2017, 30, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusama, T.; Aida, J.; Higashi, D.; Sato, Y.; Onodera, T.; Sugiyama, K.; Tsuboya, T.; Takahashi, T.; Osaka, K. Trajectory of evacuees’ health condition after the Great East Japan earthquake: Heath survey of residents in prefabricated temporary housing and private rented housing in the Miyagi Prefecture. Nihon Koshu Eisei Zasshi 2020, 67, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, R.; Tsubota-Utsugi, M.; Sasaki, R.; Shimoda, H.; Fujino, Y.; Ikaga, T.; Kano, T.; Sakata, K. Environmental risks to housing and living arrangements among older survivors of the Great East Japan Earthquake and their relationships with housing type: The RIAS Study. Nihon Koshu Eisei Zasshi 2023, 70, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugiura, M.; Sato, S.; Nouchi, R.; Honda, A.; Abe, T.; Muramoto, T.; Imamura, F. Eight personal characteristics associated with the power to live with disasters as indicated by survivors of the 2011 Great East Japan earthquake disaster. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0130349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiura, M.; Sato, S.; Nouchi, R.; Honda, A.; Ishibashi, R.; Abe, T.; Muramoto, T.; Imamura, F. Psychological processes and personality factors for an appropriate tsunami evacuation. Geosciences 2019, 9, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiura, M.; Nouchi, R.; Honda, A.; Sato, S.; Abe, T.; Imamura, F. Survival-oriented personality factors are associated with various types of social support in an emergency disaster situation. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishibashi, R.; Nouchi, R.; Honda, A.; Abe, T.; Sugiura, M. A concise psychometric tool to measure personal characteristics for surviving natural disasters: Development of a 16-item power to live questionnaire. Geosciences 2019, 9, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigekawa, L.; Tanaka, S.; Koumoto, H.; Sato, S. Housing reconstruction of disaster victims in the designated temporary housing system: Analyzing living environment aimed at smooth transition to permanent residences. J. Hous. Res. Found. 2015, 41, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatsuki, S. Systematization of Measures to Support the Reconstruction of the Lives of Survivors in Rental Temporary Housing. 2016. Available online: https://projectdb.jst.go.jp/file/JST-PROJECT-13418847/JST_1115080_13418847_2016_%E7%AB%8B%E6%9C%A8_PER.pdf (accessed on 9 March 2023).

- Reconstruction Agency. Restoration/Reconstruction of Housing/Infrastructure: Status of Evacuees/Temporary Housing. Available online: https://www.reconstruction.go.jp/topics/main-cat15/house-etc/sumai-infura_no_hukkou.html (accessed on 30 January 2023).

- Honda, A.; Sugiura, M.; Abe, T.; Muramoto, T. Personality determinants of power to live with disasters: Gratitude, grit, and self-control. Jpn. J. Res. Emot. 2019, 27, ps28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckworth, A.L.; Peterson, C.; Matthews, M.D.; Kelly, D.R. Grit: Perseverance and passion for long-term goals. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 92, 1087–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckworth, A.L.; Quinn, P.D. Development and validation of the Short Grit Scale (GRIT–S). J. Personal. Assess. 2009, 91, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishikawa, K.; Okugami, S.; Amemiya, T. Development of the Japanese Short Grit Scale (Grit-S). Jpn. J. Personal. 2015, 24, 167–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Credé, M.; Tynan, M.C.; Harms, P.D. Much ado about grit: A meta-analytic synthesis of the grit literature. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2017, 113, 492–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, K.K.L.; Zhou, M. Grit and academic achievement: A comparative cross-cultural meta-analysis. J. Educ. Psychol. 2022, 114, 597–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangney, J.P.; Baumeister, R.F.; Boone, A.L. High self-control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. J. Personal. 2004, 72, 271–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozaki, Y.; Goto, T.; Kobayashi, M.; Kutsuzawa, G. Reliability and validity of the Japanese translation of Brief Self-Control Scale (BSCS-J). Jpn. J. Psychol. 2016, 87, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willems, Y.E.; Boesen, N.; Li, J.; Finkenauer, C.; Bartels, M. The heritability of self-control: A meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2019, 100, 324–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, T. What does “being good at self-control” means? Reconceptualizing by dissociating “being good at conflict resolving” from “being good at goal achievement”. Jpn. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 63, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wennerhold, L.; Friese, M. Challenges in the conceptualization of trait self-control as a psychological construct. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2022, 17, e12726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, N.; Sugiura, M.; Nozawa, T.; Yamamoto, Y.; Sasaki, Y.; Hamamoto, Y.; Yamazaki, S.; Hirano, K.; Takahashi, M.; Kawashima, R. Taking another’s perspective promotes right parieto-frontal activity that reflects open-minded thought. Soc. Neurosci. 2020, 15, 282–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, N.; Yoshii, K.; Takahashi, M.; Sugiura, M.; Kawashima, R. Functional MRI on the ability to handle unexpected events in complex socio-technological systems: Task performance and problem-solving characteristics are associated with low activity of the brain involved in problem solving. Trans. Hum. Interface Soc. 2020, 22, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsubota-Utsugi, M.; Yonekura, Y.; Suzuki, R.; Sasaki, R.; Tanno, K.; Shimoda, H.; Ogawa, A.; Kobayashi, S.; Sakata, K. Psychological distress in responders and nonresponders in a 5-year follow-up health survey: The RIAS Study. J. Epidemiol. 2022, 32, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asanuma-Brice, C.; Evrard, O.; Chalaux, T. Why did so few refugees return to the Fukushima fallout-impacted region after remediation? An interdisciplinary case study from Iitate village, Japan. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduc. 2023, 85, 103498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, A.; Wiwattanapantuwong, J.; Abe, T. Japanese university students’ attitudes toward the Fukushima nuclear disaster. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, Y.; Yoshida, Y.; Isogai, E.; Hayase, T.; Nakamura, K.; Saito, M.; Arizono, K. Level of perception of technical terms regarding the effect of radiation on the human body by residents of Japan. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2017, 22, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, L. After Fukushima: How do news media impact Japanese public’s risk perception and anxiety regarding nuclear radiation. Environ. Commun. 2020, 14, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orui, M.; Nakayama, C.; Moriyama, N.; Tsubokura, M.; Watanabe, K.; Nakayama, T.; Sugita, M.; Yasumura, S. Current psychological distress, post-traumatic stress, and radiation health anxiety remain high for those who have rebuilt permanent homes following the Fukushima nuclear disaster. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukasawa, M.; Umeda, M.; Akiyama, T.; Horikoshi, N.; Yasumura, S.; Yabe, H.; Suzuki, Y.; Bromet, E.J.; Kawakami, N. Worry about radiation and its risk factors five to ten years after the Fukushima nuclear power plant disaster. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen, B.; Opejin, A.; Pijawka, K.D. Risk perceptions and amplification effects over time: Evaluating Fukushima longitudinal surveys. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).