Empirical Evaluation of the Impact of Informal Communication Space Quality on Innovation in Innovation Districts

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Innovation District

2.2. Innovation District Informal Communication Space

2.3. Impact of Informal Communication Space on Innovation

2.4. Space Quality Assessment for Informal Exchanges

3. Methodology and Research Design

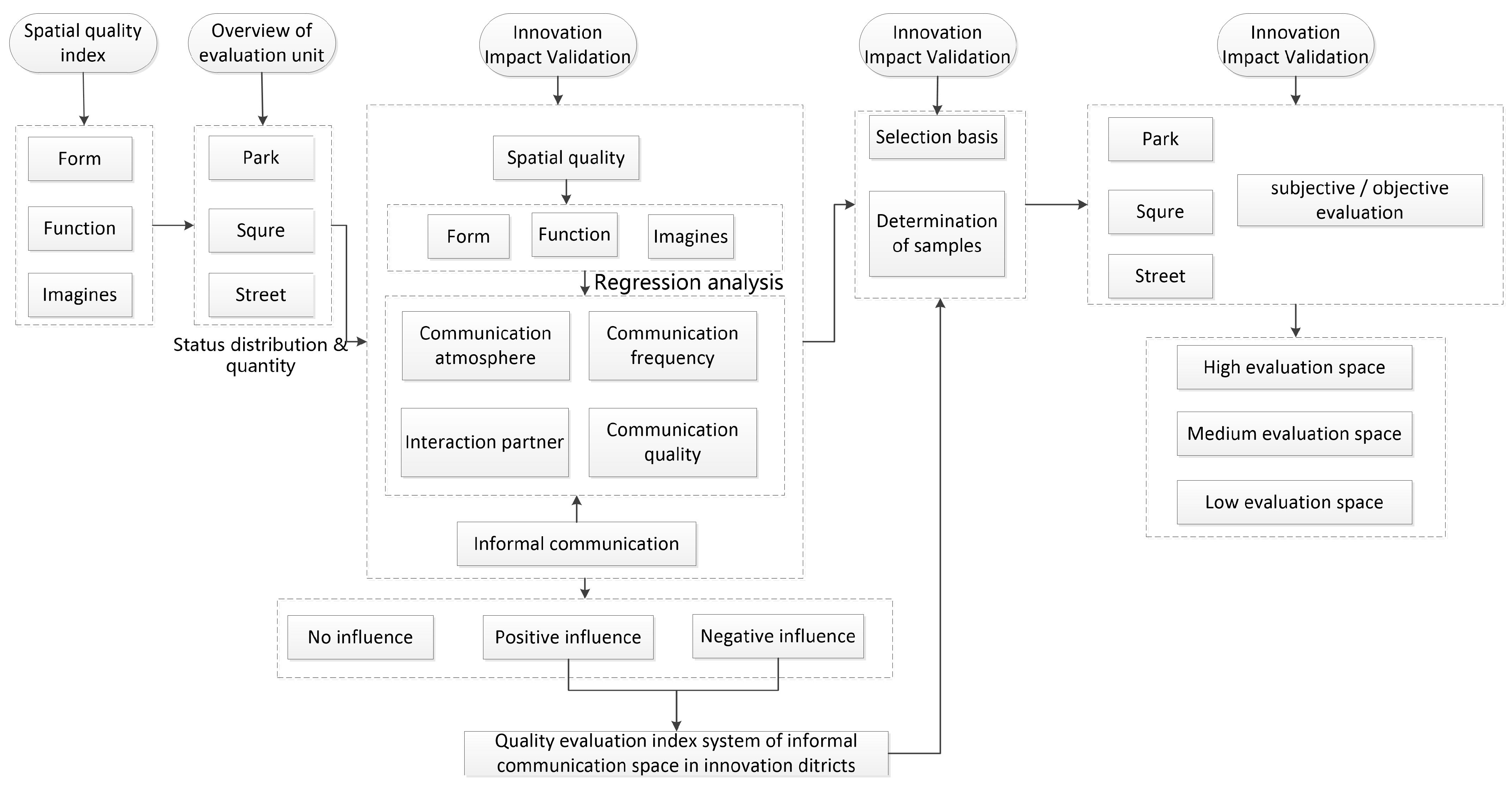

3.1. Methodology and Research Design

3.2. Construction of Spatial Quality Evaluation Index System

3.3. Case Selection and Empirical Investigation

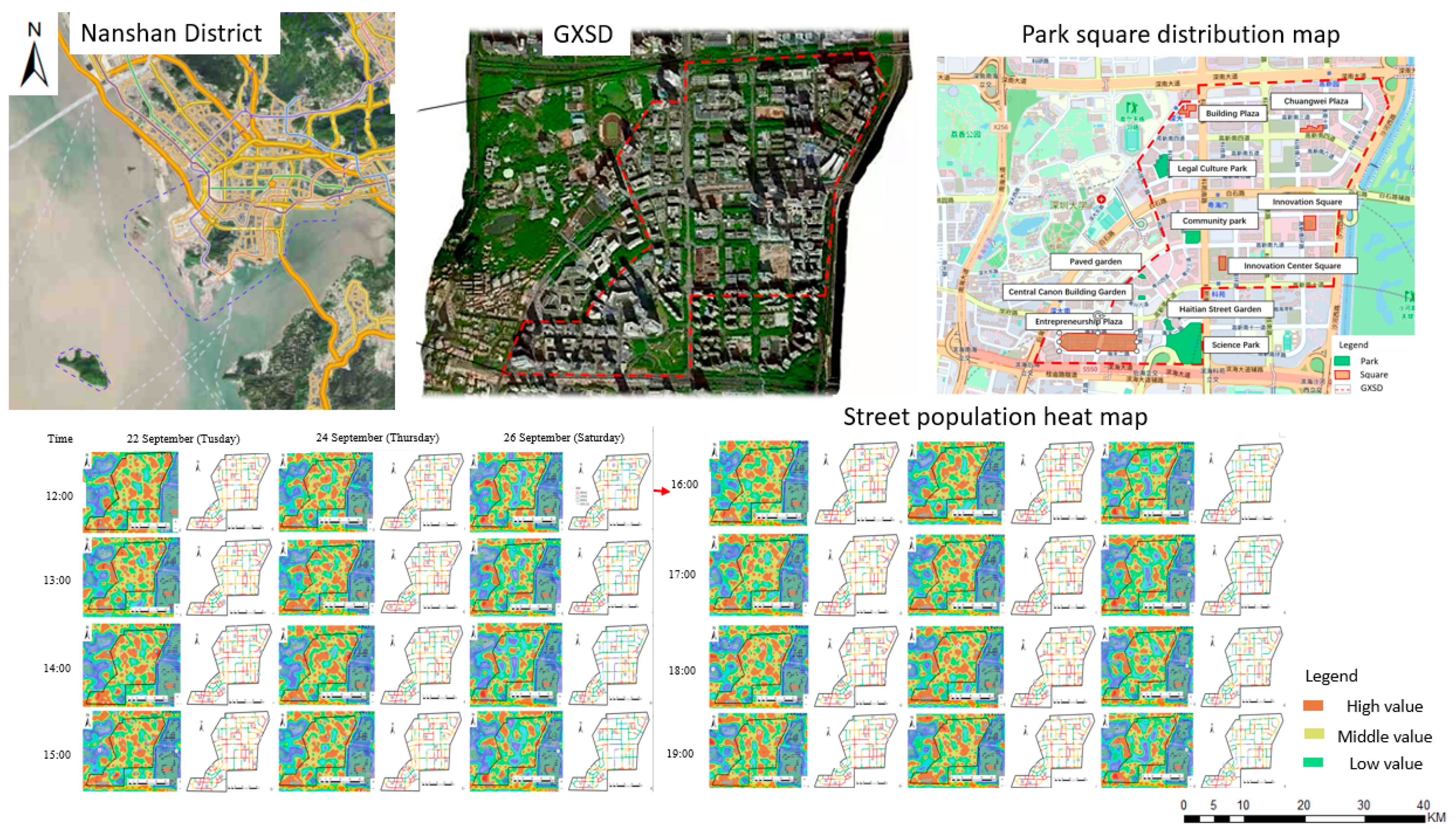

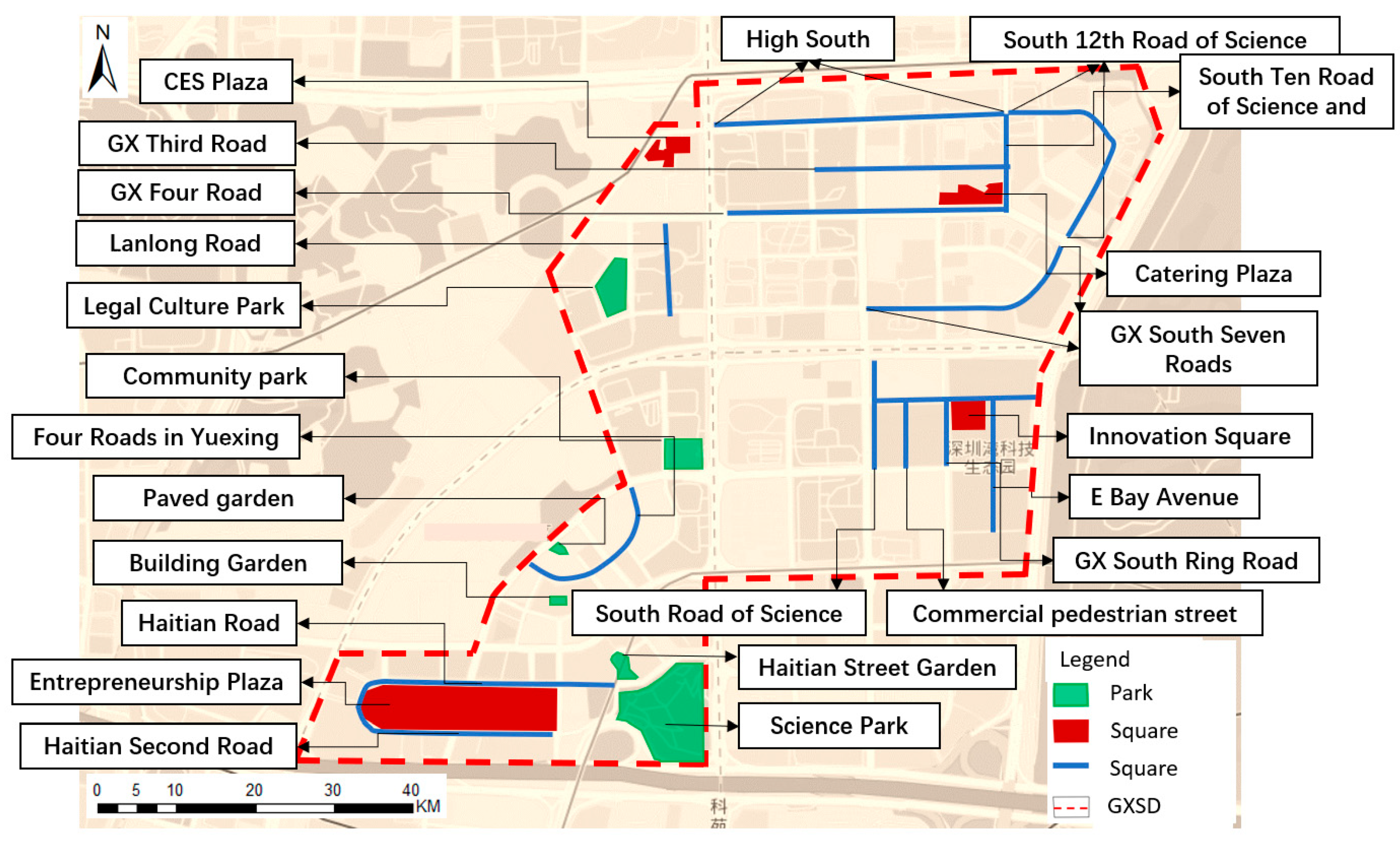

3.3.1. Case Selection

3.3.2. Empirical Investigation

4. Result

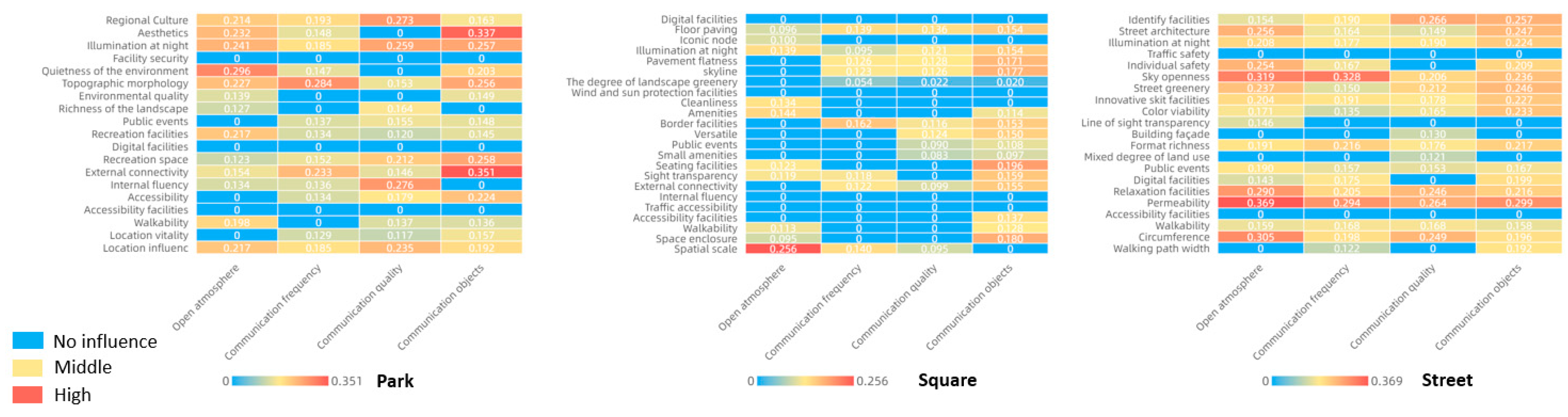

4.1. Evaluation of the Impact of Informal Communication Space Quality on Innovation

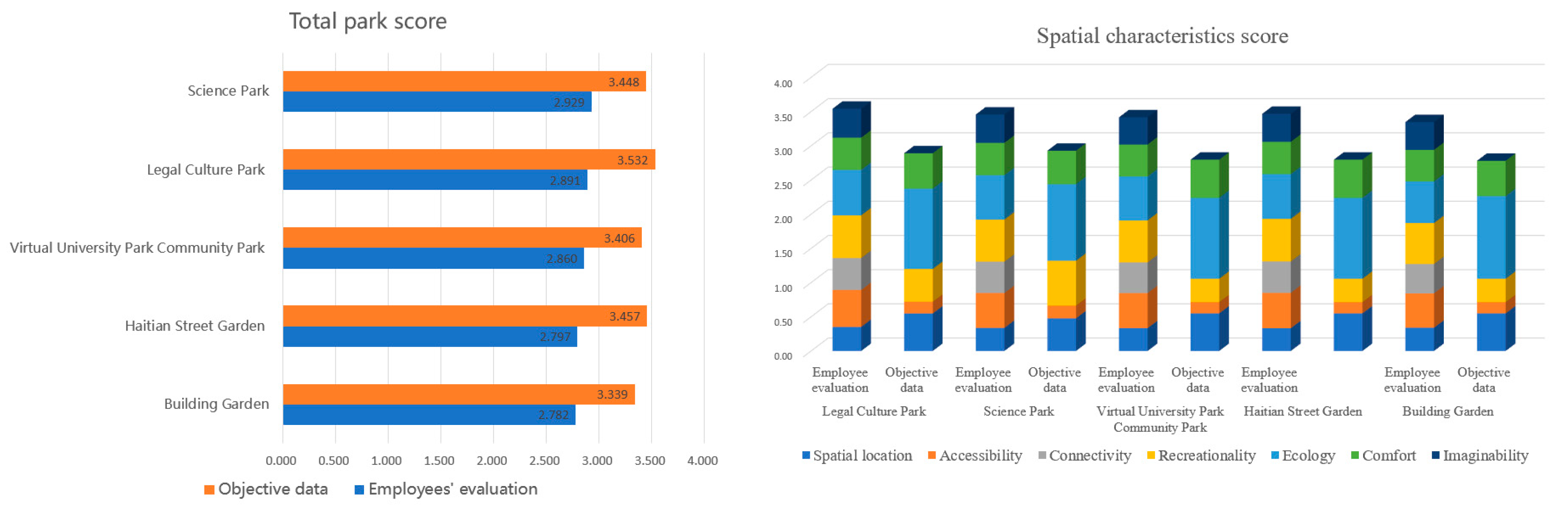

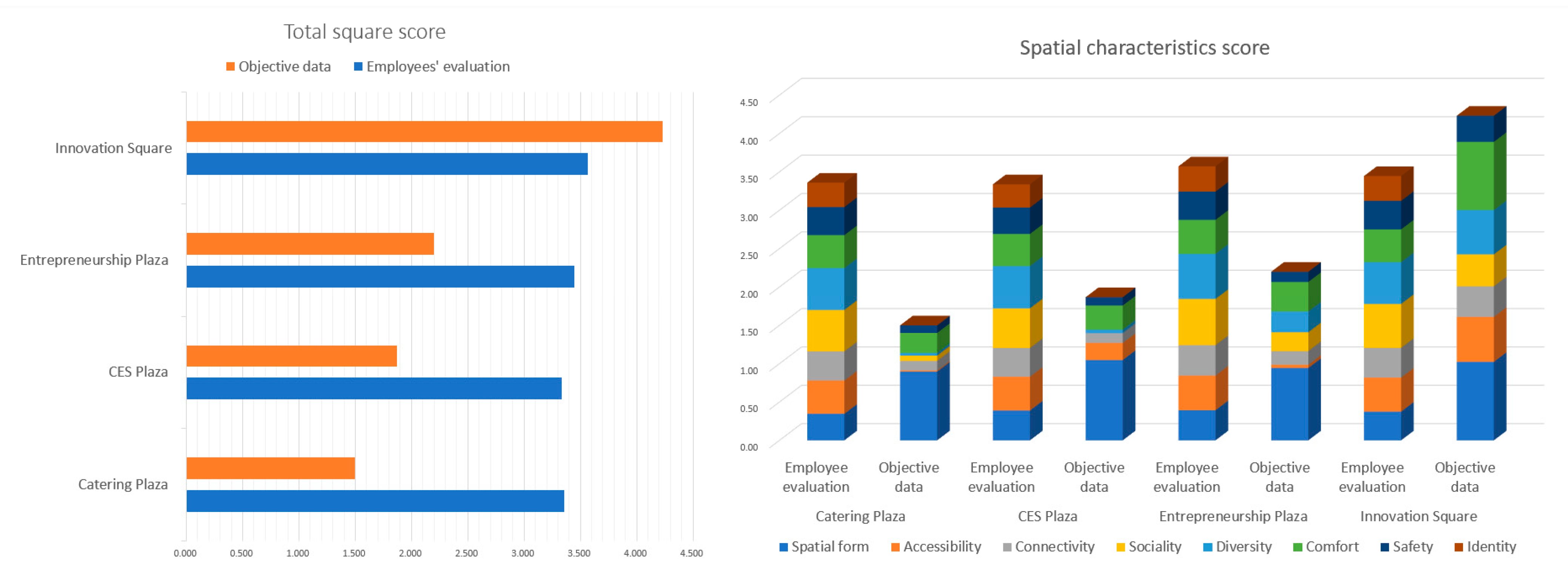

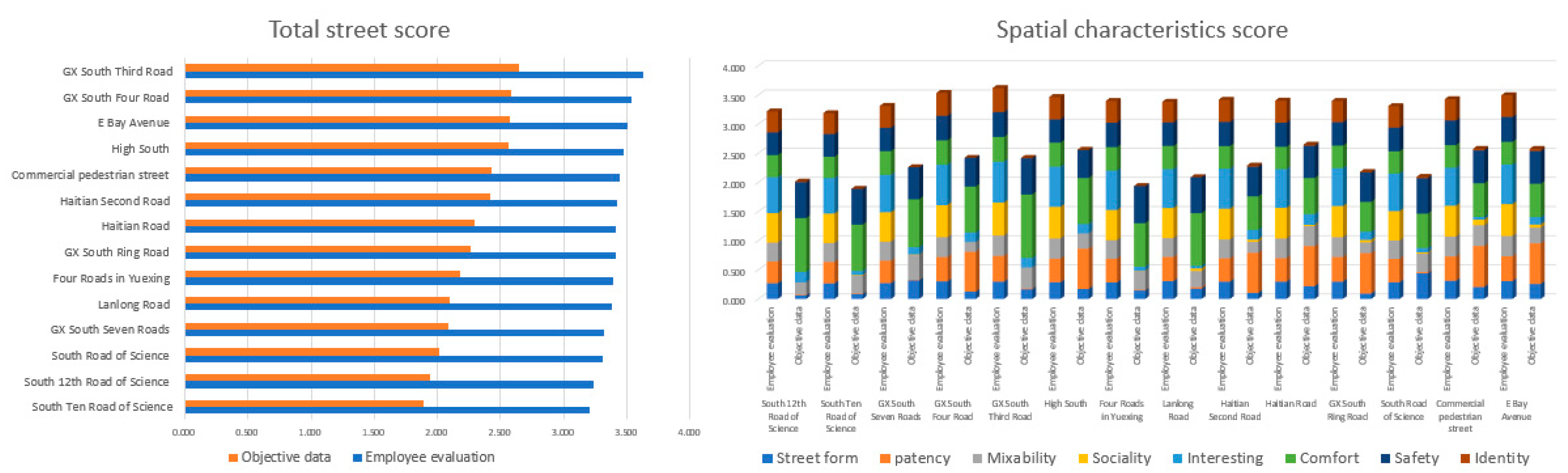

4.2. Quality Evaluation of Informal Communication Space in the Innovation District

5. Conclusions and Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chatterji, A.; Glaeser, E.; Kerr, W. Clusters of entrepreneurship and innovation. Innov. Policy Econ. 2014, 14, 129–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutton, T.A. The new economy of the inner city. Cities 2004, 21, 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florida, R.; Mellander, C. Rise of the startup city: The changing geography of the venture capital financed innovation. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2016, 59, 14–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.; Huang, H.-I.; Walsh, J.P. A typology of ‘innovation districts’: What it means for regional resilience. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2010, 3, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Winden, W.; Carvalho, L. Urbanize or perish? Assessing the urbanization of knowledge locations in Europe. J. Urban Technol. 2016, 23, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.L. Regenerating urban waterfronts—Creating better futures—From commercial and leisure market places to cultural quarters and innovation districts. Plan. Pract. Res. 2017, 32, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon, N. Attract and connect: The 22@ Barcelona innovation district and the internationalisation of Barcelona business. Innov. Policy Econ. 2008, 10, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monardo, B. Innovation districts as turbines of smart strategy policies in US and EU. Boston and barcelona experience. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on New Metropolitan Perspectives, Reggio Calabria, Italy, 22–25 May 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Yigitcanlar, T.; Inkinen, T.; Makkonen, T. Does size matter? Knowledge-based development of second-order city-regions in Finland. disP-Plan. Rev. 2015, 51, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pancholi, S.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Guaralda, M. Attributes of successful place-making in knowledge and innovation spaces: Evidence from Brisbane’s Diamantina knowledge precinct. J. Urban Des. 2018, 23, 693–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincevica-Gaile, Z.; Burlakovs, J.; Fonteina-Kazeka, M.; Wdowin, M.; Hanc, E.; Rudovica, V.; Krievans, M.; Grinfelde, I.; Siltumens, K.; Kriipsalu, M. Case Study-Based Integrated Assessment of Former Waste Disposal Sites Transformed to Green Space in Terms of Ecosystem Services and Land Assets Recovery. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, I.; Petruska, I. Operational characteristics of Hungarian innovation clusters as reflected by a qualitative research study. Period. Polytech. Soc. Manag. Sci. 2014, 22, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Huang, Q.; Dou, J.; Zhao, X. The impact of informal social interaction on innovation capability in the context of buyer-supplier dyads. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 78, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, C.M.; Woo, S.E. Untangling the networking phenomenon: A dynamic psychological perspective on how and why people network. J. Manag. 2015, 41, 1477–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenkel, A. High-tech firms’ location considerations within the metropolitan regions and the impact of their development stages. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2012, 20, 231–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arauzo-Carod, J.-M. Location determinants of high-tech firms: An intra-urban approach. Ind. Innov. 2021, 28, 1225–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Qiu, P.; Dou, J. The impact of borders and distance on knowledge spillovers—Evidence from cross-regional scientific and technological collaboration. Technol. Soc. 2022, 70, 102014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasselli, S.; Kilduff, M.; Menges, J.I. The microfoundations of organizational social networks: A review and an agenda for future research. J. Manag. 2015, 41, 1361–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volberda, H.W.; Foss, N.J.; Lyles, M.A. Perspective—Absorbing the concept of absorptive capacity: How to realize its potential in the organization field. Organ. Sci. 2010, 21, 931–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salavisa, I.; Sousa, C.; Fontes, M. Topologies of innovation networks in knowledge-intensive sectors: Sectoral differences in the access to knowledge and complementary assets through formal and informal ties. Technovation 2012, 32, 380–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Diez, J.R.; Schiller, D. Interactive learning, informal networks and innovation: Evidence from electronics firm survey in the Pearl River Delta, China. Res. Policy 2013, 42, 635–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M. Spatial Qualities of Innovation Districts: How Third Places Are Changing the Innovation Ecosystem of Kendall Square; Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Huang, Y.; Ma, X. Evaluation of the accessible urban public green space at the community-scale with the consideration of temporal accessibility and quality. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 131, 108231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Feng, T.; Timmermans, H.J. Heterogeneity in outdoor comfort assessment in urban public spaces. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 790, 147941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Z.; Jiejing, W.; Bo, Q.J.L. Quantity or quality? Exploring the association between public open space and mental health in urban China. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 213, 104128. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, K.W.; Mak, C.M.; Wong, H.M. Effects of environmental sound quality on soundscape preference in a public urban space. Appl. Acoust. 2021, 171, 107570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalili, A.; Fallah, S.N. Role of social indicators on vitality parameter to enhance the quality of women׳ s communal life within an urban public space (case: Isfahan׳ s traditional bazaar, Iran). Front. Archit. Res. 2018, 7, 440–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, I.Y.; Chan, E.H.; Xu, Y.; Owusu, E.K. Inclusive public open space for all: Spatial justice with health considerations. Habitat Int. 2021, 118, 102457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kholei, A.O.; Yassein, G. Professionals’ perceptions for designing vibrant public spaces: Theory and praxis. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2022, 13, 101727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarrete-Hernandez, P.; Vetro, A.; Concha, P. Building safer public spaces: Exploring gender difference in the perception of safety in public space through urban design interventions. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 214, 104180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pancholi, S.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Guaralda, M.; Phillips, F. Place making for innovation and knowledge-intensive activities: The Australian experience. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 146, 616–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huggins, R. The Evolution of Knowledge Clusters: Progress and Policy. Econ. Dev. Q. 2008, 22, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, G. Creative cities, creative spaces and urban policy. Urban Stud. 2009, 46, 1003–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T.; Velibeyoglu, K.; Martinez-Fernandez, C. Rising knowledge cities: The role of urban knowledge precincts. J. Knowl. Manag. 2008, 12, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pancholi, S.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Guaralda, M. Does place quality matter for innovation districts? Determining the essential place characteristics from Brisbane’s knowledge precincts. Land Use Policy 2018, 79, 734–747. [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishnan, M.; Shrestha, A.; Soar, J. Innovation centric knowledge commons—A systematic literature review and conceptual model. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, B.; Wagner, J. The Rise of Innovation Districts: A New Geography of Innovation in America; Brookings Institution: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; Available online: http://www.brookings.edu/ (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Julie, W.; Bruce, K.; Osha, T. The Evloution of Innovation District. 2019. Available online: https://www.giid.org/the-evolution-of-innovation-districts/ (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Morisson, A. A Framework for Defining Innovation Districts—Case Study from 22@ Barcelona; Social Science Electronic Publishing: Rochester, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Saxenian, A. Regional Advantage: Culture and Competition In Silicon Valley and Route 128, with a New Preface by the Author; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Oldenburg, R.; Brissett, D. The third place. Qual. Sociol. 1982, 5, 265–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florida, R. Cities and the creative class. City Community 2003, 2, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zukin, S. Naked City: The Death and Life of Authentic Urban Places; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Evers, H.-D. Knowledge Hubs and Knowledge Clusters: Designing a Knowledge Architecture for Development; Munich Personal RePEc Archive: Munich, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Y. Making space and place for the knowledge economy. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2010, 18, 1769–1786. [Google Scholar]

- Pancholi, S.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Guaralda, M. Governance that matters: Identifying place-making challenges of Melbourne’s Monash Employment Cluster. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2017, 10, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, J. The extended workplace in a creative cluster: Exploring space (s) of digital work in silicon roundabout. J. Urban Des. 2015, 20, 125–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuffrida, G.; Clark, J.; Cross, S. Putting Innovation in Place: Georgia Tech’s Innovation Neighbourhood of Tech Square. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Innovation and Entrepreneurship, Genoa, Italy, 17–18 September 2015. [Google Scholar]

- McCann, P. Sketching out a model of innovation, face-to-face interaction and economic geography. Spat. Econ. Anal. 2007, 2, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storper, M.; Venables, A.J. Buzz: Face-to-face contact and the urban economy. J. Econ. Geogr. 2004, 4, 351–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peschl, M.F.; Fundneider, T. Spaces enabling game-changing and sustaining innovations: Why space matters for knowledge creation and innovation. J. Organ. Transform. Soc. Chang. 2012, 9, 41–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeilpoorarabi, N.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Guaralda, M. Towards an urban quality framework: Determining critical measures for different geographical scales to attract and retain talent in cities. Int. J. Knowl.-Based Dev. 2016, 7, 290–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azudin, N.; Ismail, M.N.; Taherali, Z. Knowledge sharing among workers: A study on their contribution through informal communication in Cyberjaya, Malaysia. Knowl. Manag. E-Learn. Int. J. 2009, 1, 139–162. [Google Scholar]

- Jarrahi, M.; Sawyer, S. Informal Networks of Innovation. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Academy of Management, Montréal, QC, Canada, 6–10 August 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Giuliani, E. Networks of innovation. In Handbook of Regional Innovation and Growth; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kloosterman, R.C.; Trip, J.J. Planning for quality? Assessing the role of quality of place in current Dutch planning practice. J. Urban Des. 2011, 16, 455–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X. Cultural industries and creative clusters in Shanghai. City Cult. Soc. 2014, 5, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballas, D. What makes a ‘happy city’? Cities 2013, 32, S39–S50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darchen, S.; Tremblay, D.-G. What attracts and retains knowledge workers/students: The quality of place or career opportunities? The cases of Montreal and Ottawa. Cities 2010, 27, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PPS. What Make a Successful Place. 2018. Available online: https://www.pps.org (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Esmaeilpoorarabi, N.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Guaralda, M. Place quality in innovation clusters: An empirical analysis of global best practices from Singapore, Helsinki, New York, and Sydney. Cities 2018, 74, 156–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mafi-Gholami, D.; Feghhi, J.; Danehkar, A.; Yarali, N. Classification and Prioritization of Negative Factors Affecting on Mangrove Forests Using Delphi Method (a Case Study: Mangrove Forests of Hormozgan Province, Iran). Adv. Biores. 2015, 6, 78–92. [Google Scholar]

- Norouzian-Maleki, S.; Bell, S.; Hosseini, S.-B.; Faizi, M. Developing and testing a framework for the assessment of neighbourhood liveability in two contrasting countries: Iran and Estonia. Ecol. Indic. 2015, 48, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biagioli, M. The case for informal spaces in the workplace. In Integrating Art and Creativity into Business Practice; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2017; pp. 55–73. [Google Scholar]

- Penn, A.; Desyllas, J.; Vaughan, L. The space of innovation: Interaction and communication in the work environment. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 1999, 26, 193–218. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Yaseen, A.M. The Physical Settings and Informal Interaction in Workplaces, the Role of Spatial Structure in Supporting Informal Communication in Organisations; Stax: Perth, Australia, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlan, A.S. The Impact of Facilities on Informal Communication in Workplaces; Stax: Perth, Australia, 1997. [Google Scholar]

| Theme | Category | Indicator | Category | Indicator | Category | Indicator |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Park | Square | Street | ||||

| Form | Spatial location | Location influence | Spatial morphology | Spatial scale | Street morphology | Walking path width |

| Location vitality | Space enclosure | Circumference | ||||

| Accessibility | Walkability | Accessibility | Walkability | Patency | Walkability | |

| Accessibility facilities | Accessibility facilities | Accessibility facilities | ||||

| Traffic accessibility | Traffic accessibility | Permeability | ||||

| Connectivity | Internal fluency | Connectivity | Internal fluency | — | — | |

| External connectivity | External connectivity | — | ||||

| — | Sight transparency | — | ||||

| Function | Recreational | Recreation space | Sociable | Seating facilities | Sociable | Relaxation facilities |

| Digital doilies | Small amenities | Digital facilities | ||||

| Recreation facilities | Public events | Public events | ||||

| Public events | — | — | ||||

| Ecology | The richness of the landscape | Diversity | Versatile | Mixability | Mixed degree of land use | |

| Environmental quality | Border facilities | Format richness | ||||

| Topographic morphology | Amenities | Interesting | Building façade | |||

| — | — | — | — | Line of sight transparency | ||

| — | — | Color viability | ||||

| — | — | Innovative skit facilities | ||||

| Image | Comfort | The quietness of the environment | Comfort | Cleanliness | Comfort | Street greenery |

| Facility security | Wind and sun protection facilities | Sky openness | ||||

| Illumination at night | The degree of landscape greenery | — | ||||

| Can be imagery | Aesthetics | skyline | — | |||

| Regional culture | Security | Pavement flatness | Security | Individual safety | ||

| — | — | Illumination at night | Traffic safety | |||

| — | — | Illumination at night | ||||

| — | Identity | Iconic node | Identity | Street architecture | ||

| — | Digital facilities | Identify facilities | ||||

| — | Floor paving | — | ||||

| Type | Park | Square | Street | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Questionnaire content | Innovation Impact Scale | Quality Evaluation | Innovation Impact Scale | Quality Evaluation | Innovation Impact Scale | Quality Evaluation |

| Number of indicators | 23 | —— | 27 | —— | 25 | —— |

| Recycle questionnaires | 281 | 403 | 426 | 506 | 364 | 432 |

| Total valid questionnaire | 265 | 389 | 396 | 472 | 336 | 408 |

| Questionnaires are efficient | 94.31% | 96.53% | 92.96% | 93.28% | 92.31% | 94.44% |

| Cronbach’s α | 0.83 | 0.91 | 0.70 | 0.87 | 0.86 | 0.92 |

| Subjective–Objective Rating | Informal Space Name | |

|---|---|---|

| High evaluation | ‘High–High’ | E Bay Avenue |

| Mid evaluation | ‘Medium–Medium’ | Virtual University Park Community Park, Haitian Street Garden, High-tech South Road, Lanlong Road, High-tech South Ring Road, High-tech South Seven Road, Haitian Second Road |

| ‘High–Middle’ | Entrepreneurship Square, Legal Culture Park, High-tech South Third Road, and High-tech South Fourth Road | |

| ‘Medium–High’ | Science Park, Innovation Square, Commercial Pedestrian Street, Haitian Road | |

| Low evaluation | ‘Low–Low’ | Street Garden of Civil-military Integration, South Tenth Road of Science and Technology, South Twelveth Road of Science and Technology |

| ‘Medium–Low’ | Catering Square, Four Roads in Yuexing | |

| ‘Low–Middle’ | Garden, CES Plaza, South Road of Science and Technology, China Connor Building | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tan, Y.; Qian, Q.; Chen, X. Empirical Evaluation of the Impact of Informal Communication Space Quality on Innovation in Innovation Districts. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5761. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15075761

Tan Y, Qian Q, Chen X. Empirical Evaluation of the Impact of Informal Communication Space Quality on Innovation in Innovation Districts. Sustainability. 2023; 15(7):5761. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15075761

Chicago/Turabian StyleTan, Youwei, Qinglan Qian, and Xiaolan Chen. 2023. "Empirical Evaluation of the Impact of Informal Communication Space Quality on Innovation in Innovation Districts" Sustainability 15, no. 7: 5761. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15075761

APA StyleTan, Y., Qian, Q., & Chen, X. (2023). Empirical Evaluation of the Impact of Informal Communication Space Quality on Innovation in Innovation Districts. Sustainability, 15(7), 5761. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15075761