Local Territorial Practices Inform Co-Production of a Rewilding Project in the Chilean Andes

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Mixed Methods

2.3. Interviews

2.4. Questionnaire

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Ethics

3. Results

3.1. Interviews

3.1.1. Local Territorial Practices in the Mountains

“…200 [years] the peasants have been here and those peasants, over time, became arrieros. What does that mean? That they started to herd livestock, that they were the only ones who had the capacity and the shrewdness, that they knew the strategic points where to pass through and where to go (…) Arrieros transported and bartered, in the old days, barter, here and there and thanks to this, the conversion [to being arrieros] started.”

“Arrieros in general herd their animals in lands that are national lands or some fundo [private landholding]. If an arriero had a fundo, he wouldn’t be an arriero, let’s start with that. An arriero is a person who has certain territorial characteristics and lives around moving animals in the mountains. They might be cattle, sheep, goats, or even horses.”

“I spent the whole month in charge of the animals, every day I was watching them, some pregnant cows would appear, I enjoyed myself, I had to find the little calves, lots of things, milk the cows to get rid of the milk because sometimes they accumulate a lot of milk (…) Sometimes you miss friends to go around with you (…) You are almost always by yourself, the fundos [landholdings] are closed, sometimes in the evening you have to herd the livestock and close them up in the corral and lock them in and then… sleep alone, the next day make a fire, put on the kettle, make your coffee, as was one’s tradition, in the countryside, the countryside… Yes men of the countryside, many can… I for example…had to do everything, let’s say cook for myself, make bread, so many things, lassos, the equipment for the horses, the reins… the sheep skins for the saddle.”

“They are disappearing, the people who know the mountain passes, who know how to recognize where to take refuge, who know how to read the nature of a place. So these kinds of people are disappearing. As they disappear, history is lost.”

“Yes, it has changed…of course, the difference is that for example before, the older people took their children out very little so that they would learn, so from one moment to the other livestock raising was lost, why? Because of course if… I bring my son [to the mountains] because they learn here, they like it, but imagine if I had never brought them…”

“Here there was the El Sauce stream, but it grew a lot [the stream], you cannot go on walking, you had to go through the trees, it rained, it snowed a lot and now we are scared because we are already drying up.”

“…the government wants to exterminate the livestock farmers.”

3.1.2. Local Adaptations to the Environment

“Now all those passes are closed and prohibited. Here it is prohibited, not just anyone can enter because of the issue of the gas pipeline.”

“I had [goats] for ten years…[until] Pinochet [dictator from 1973 to 1990] stopped us. The frontier was closed for three years and so the mountains were closed for the spring pastures.”

“There was an opportunity for reconversion to the extent that tourism was a source of opportunities that could be added on to the lifestyle of the arriero, which indeed involves a lot of sacrifice, because it is a very dry and hard mountain range. So, beyond the issue of grass, water and the mines, this makes the [activities] of an arriero increasingly hard to carry out.”

“In some areas yes they are united, for floods and things like that they are united, but the unity lasts for a while and then they come apart. There are sectors that are more united, [in] Río Colorado they have made associations and things like that… In San Gabriel it is not so united and in San José just from time to time.”

3.1.3. Local Ecological Knowledge

“…in the past it was very very rainy, it rained day and night, two days, three days, there were huge snowfalls…and the old people and housewives had to make a path with a shovel to get to the houses in the fundo [landholding]…”

“The drought is the biggest threat. It will be just like in the north, the desert. Maybe I won’t see it, but my children will. I remember that 20–30 years ago there was like 40 cm of snow and now imagine, it has all dried up. Now you go to the mountain range and it is just like being here, before wherever you went in any ravine it gave you pleasure to wash your face and drink water, but now you have to go for kilometers to find a ravine with water, it has all dried up.”

“Well, what happens is that the arriero has to have an education. But an education, you see it as…they laugh because what education is one going to have in the mountains, but I stupidly call it that anyway. He has to have an education, let’s call it that or we can change it and say, the respect that you have to practice in the mountains, a special respect. The arriero has to know it (…) [I]f it’s really good for going on a trip, it’s because there are some tourists who are going to pay me like 40,000 pesos per person and I have to spend like two days up there and it’s good weather, but if you see that it is bad [weather], better not to get mixed up in it.”

“When there is more snow, the springs increase, they flowed to the Maipo river and through it, the river branches that you can find around there… they had more water […] and then, it snows a lot up there, it rains, it snows, the tagua [possibly Fulica armillata] will arrive here downstream, through the ravines and they are going to go to the Maipo river and the river will grow downstream.”

“…the guanaco snatched himself off to the mountains because they belong to the high peaks.”

“…[the guanacos] would be up in the mountains so they wouldn’t influence me at all.”

“For me it would be good that there should be guanacos, for all the livestock farmers, because they are going to provide meat to the pumas. We will save ourselves because [the puma] hunts mainly guanaco.”

“[Guanacos] would just be meat for [pumas] (…) That would be good because the pumas wouldn’t attack our colts and would have their own food, obviously they wouldn’t come down here.”

“…it is to be hoped that there will be more variety of hunting for the puma, and the other is that equally nature is prettier like that with animals that are different, different from whatever the horse or the cow that we are accustomed to but those animals, for instance a fox or a couple of guanacos would look nice.”

“The condor, which around here they call a vulture, was killing the offspring right away, so the cows were giving birth and before they even gave birth the condor picked them off.”

“Many people say that the condor is a scavenger, and yes, it is a scavenger, but an animal doesn’t die every day to maintain so many condors, so the condor has to hunt, it’s the law of nature (…) They kill our calves, the cows give birth and there are no more calves.”

“[The pumas] eat foals and calves (the latter they didn’t eat before, because they say that the puma prefers prey that runs, and the calves are too curious [to run away]).”

“Before, pumas didn’t eat calves. What happened is that they are these tame pumas, the ones they [supposedly CONAF] release and bring from down below [in the lowlands]. Once the puma starts to eat calves, it starts to move among people. It will start to eat people next. Before, there were only mountain pumas that when they saw you with dogs they would run away.”

3.1.4. Perception of Guanaco Reintroductions

“Many people will come and they are going to bring them and all that, like the people who rustle livestock […] as they used to call them in the old days, they are going to come and hunt, they are going to go around at night.”

“Down here they are going to eat them or they are going to scare them. The dogs themselves will eat them.”

“It is not possible, I believe that you cannot do it, guanacos move away from people, they go away, they stay away, the guanaco is an animal that loves to live in solitude, in their mountains, for example in Argentina.”

“This idea of putting [guanacos] in a site is a business for the owners. (…) Imagine, to give you an example, here in Laguna Negra they put in some guanacos, the chamber of tourism takes charge because they are really interested in this area, they install gates, the arrieros won’t be able to enter there, nobody will be able to enter, only people in vehicles up to a certain area, they will charge an entrance fee and all that (…) What do we get out of it? Absolutely nothing, we will have to take out the livestock and will be left in a worse state than we are now.”

“The owners of fields would be negatively affected. Suppose that 100 guanacos arrive in a field […] they will eat all the pasture and the owner will not be able to rent it [as livestock pasture].”

3.1.5. Perception of Carnivores

“Dog packs or the very dogs from the tourists themselves will end up attacking guanacos. There must be education, it is like a cycle. It is not only [enough] to arrive and reintroduce them. I think there must be education for livestock farmers and arrieros, and [you must] educate the community.”

“Raising horses has no benefit now because you have to wait one year for the mare to give birth and have the colts at home. When they are 9 months old, they are released and the next day a puma has eaten the offspring. [Raising horses] is plagued by pumas.”

“[The reintroduction of guanacos] would help with puma [attacks on livestock], because the puma maybe will follow the guanaco, once the guanaco has arrived, it is going to prefer guanaco meat to foal meat.”

3.2. Questionnaire

3.2.1. Socio-Economic Profile

3.2.2. Plant and Animal Resources

3.2.3. Knowledge of Guanacos

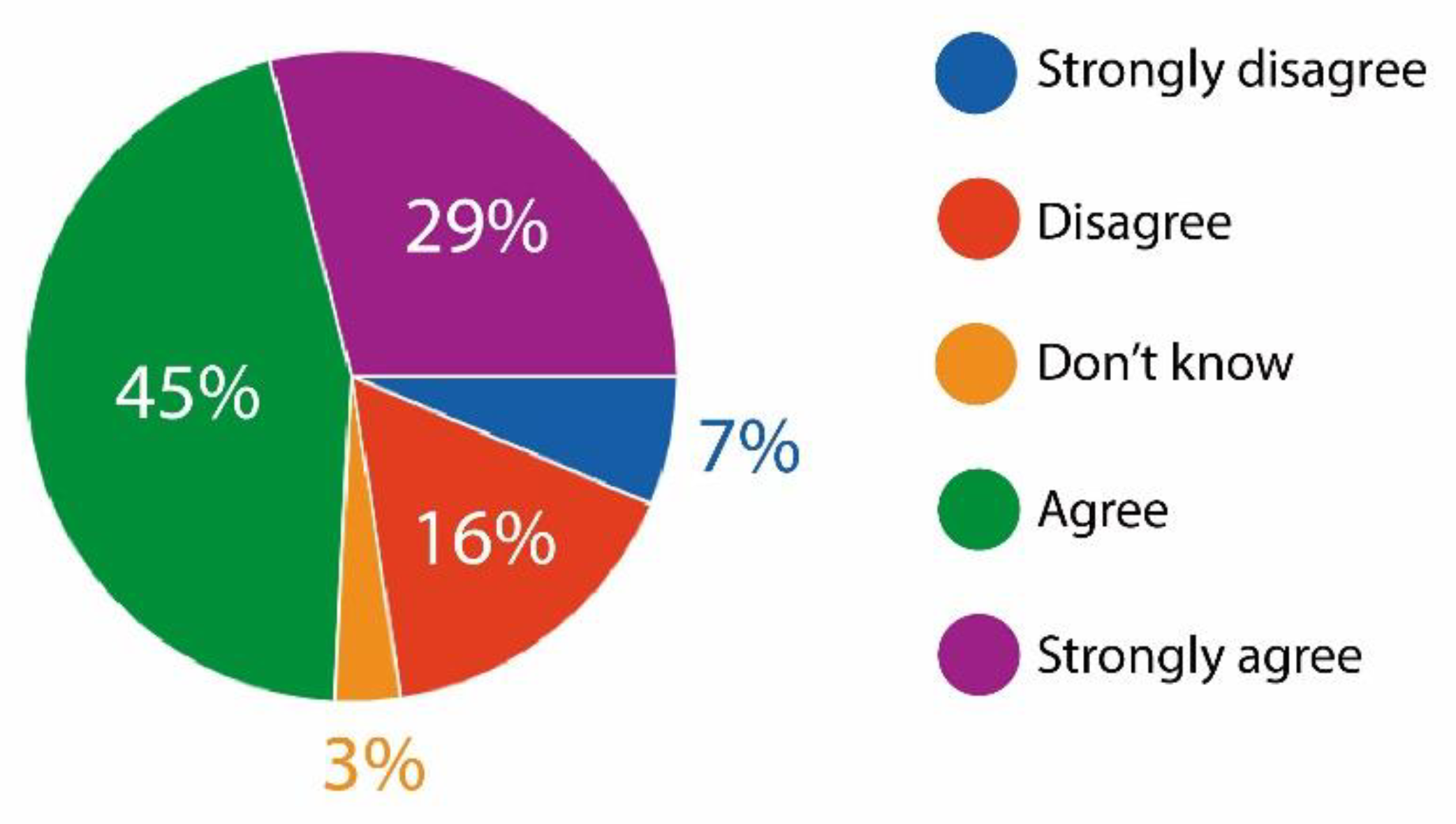

3.2.4. Attitudes to Guanaco Reintroduction

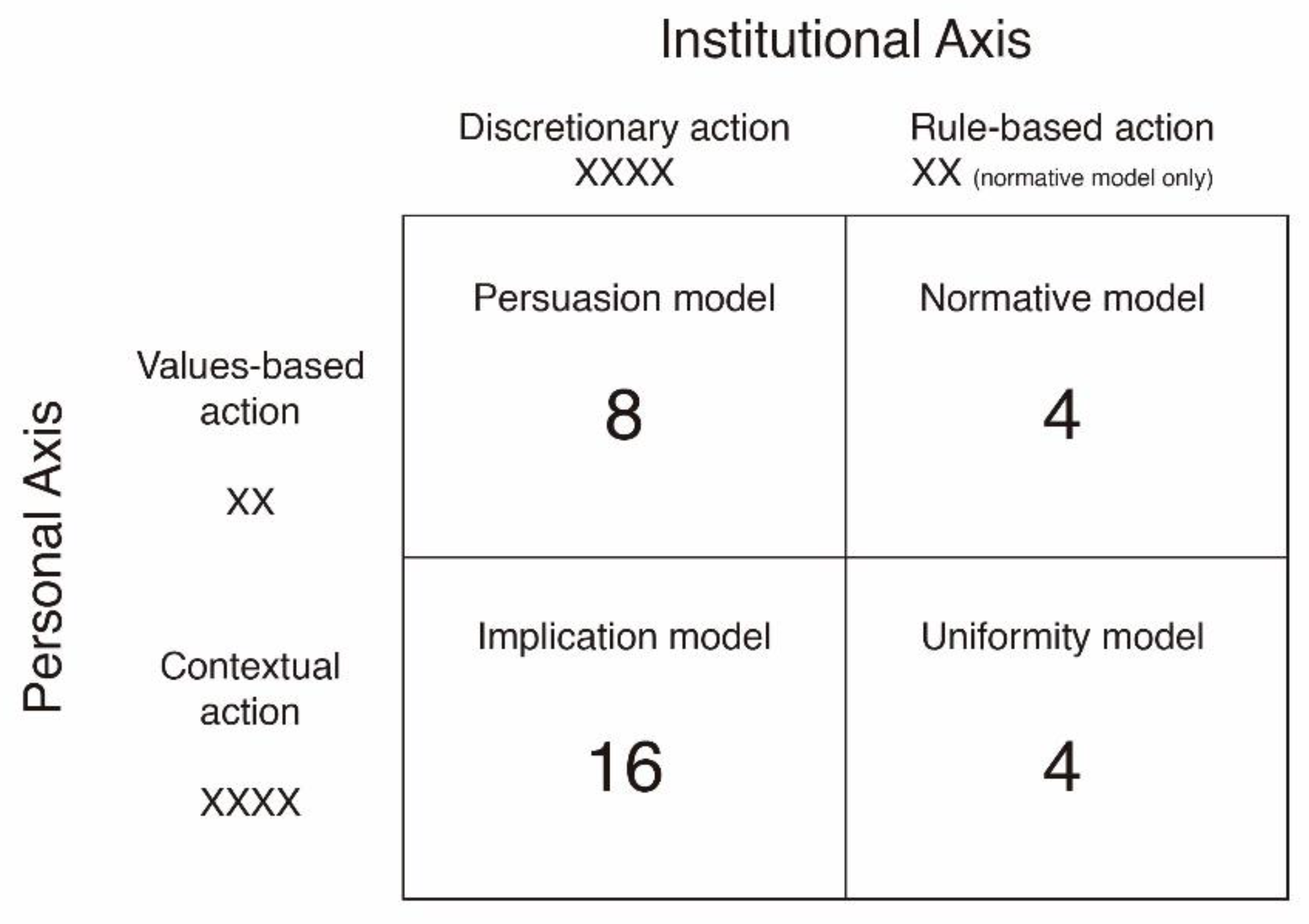

3.2.5. Design of a Reintroduction Project

3.2.6. Responsible Dog Ownership

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Berkes:, F. Rethinking Community-Based Conservation. Conserv. Biol. 2004, 18, 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyborn, C.; Datta, A.; Montana, J.; Ryan, M.; Leith, P.; Chaffin, B.; Miller, C.; van Kerkhoff, L. Co-Producing Sustainability: Reordering the Governance of Science, Policy, and Practice. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2019, 44, 319–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, N.C.; Kröger, M. The Potential of Amazon Indigenous Agroforestry Practices and Ontologies for Rethinking Global Forest Governance. For. Policy Econ. 2020, 118, 102257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagannathan, K.; Arnott, J.C.; Wyborn, C.; Klenk, N.; Mach, K.J.; Moss, R.H.; Sjostrom, K.D. Great Expectations? Reconciling the Aspiration, Outcome, and Possibility of Co-Production. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2020, 42, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latulippe, N.; Klenk, N. Making Room and Moving over: Knowledge Co-Production, Indigenous Knowledge Sovereignty and the Politics of Global Environmental Change Decision-Making. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2020, 42, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norström, A.V.; Cvitanovic, C.; Löf, M.F.; West, S.; Wyborn, C.; Balvanera, P.; Bednarek, A.T.; Bennett, E.M.; Biggs, R.; de Bremond, A.; et al. Principles for Knowledge Co-Production in Sustainability Research. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 3, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broughton, R.K.; Bullock, J.M.; George, C.; Gerard, F.; Maziarz, M.; Payne, W.E.; Scholefield, P.A.; Wade, D.; Pywell, R.F. Slow Development of Woodland Vegetation and Bird Communities during 33 Years of Passive Rewilding in Open Farmland. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0277545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Root-Bernstein, M.; Svenning, J.C. Restoring Connectivity between Fragmented Woodlands in Chile with a Reintroduced Mobile Link Species. Perspect. Ecol. Conserv. 2017, 15, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, H.M.; Navarro, L.M. Rewilding European Landscapes; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; ISBN 9783319120393. [Google Scholar]

- Zamboni, T.; di Martino, S.; Jiménez-Pérez, I. A Review of a Multispecies Reintroduction to Restore a Large Ecosystem: The Iberá Rewilding Program (Argentina). Perspect. Ecol. Conserv. 2017, 15, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindon, A.; Root-Bernstein, M. Phoenix Flagships: Conservation Values and Guanaco Reintroduction in an Anthropogenic Landscape. Ambio 2015, 44, 458–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aliste, E.; Núñez, A. Geografías del Devenir: Narración y Hermenéutica Geográfica; Librería LOM: Santiago, Chile, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Di Méo, G. Géographies Tranquilles du Quotidien. Une Analyse de la Contribution des Sciences Sociales et de La Géographie à l’étude des Pratiques Spatiales. Cah. Géogr. Qué. 2005, 43, 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Di Méo, G.; Buléon, P. L’espace Social: Lecture Géographieque Des Sociétés. Investig. Geogr. 2007, 64, 153–155. [Google Scholar]

- Escobar, A. El Lugar de La Naturaleza y La Naturaleza Del Lugar: Globalización o Postdesarrollo? In La Colonialidad del Saber: Eurocentrismo y Ciencias Sociales. Perspectivas Latinoamericanas; CLACSO—Consejo Latinoamericano de Ciencias Sociales: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2000; pp. 68–87. ISBN 9781626239777. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. Justicia, Naturaleza y la Geografía de la Diferencia; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 1996; ISBN 9788494806827. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, D. Un Sentido Global Del Lugar. In Doreen Massey. Un Sentido Global del Lugar; Albet, A., Benach, N., Eds.; Icaria Editorial: Barcelona, Spain, 2012; pp. 112–129. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, D. Geometrías Del Poder y La Conceptualización Del Espacio. Conf. Dictada Univ. Cent. Venez. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Escobar, A. Sentipensar Con La Tierra Nuevas Lecturas Sobre Desarrollo, Territorio y Diferencia; Ediciones Unaula: Medellín, Colombia, 2014; ISBN 9789588869148. [Google Scholar]

- Porto-Gonçalves, C.W. Da Geografia Às Geo-Grafias. Um Mundo Em Busca de Novas Territorialidades. Instituto de Investigaciones Histórico-Sociales, Universidad Veracruzana: Xalapa, Mexico, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Amigo-Jorquera, C.; Urquiza Gómez, A. Transdisciplina e Interfaz: Dos Lados de Una Misma Forma. In Inter-y Transdisciplina en la Educación Superior Latinoamericana; Universidad de Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2022; pp. 13–34. [Google Scholar]

- Molnár, Z.; Babai, D. Inviting Ecologists to Delve Deeper into Traditional Ecological Knowledge. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2021, 36, 679–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Root-Bernstein, M.; du Plessis, P.; Guerrero-Gatica, M.; Narayan, T.; Roturier, S.; Wheeler, H. What Are Indigenous and Local Knowledges in Relation to Science? Using the ‘Ethic of Equivocation’ to Co-Produce New Knowledge For. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingold, T. The Temporality of the Landscape. World Archaeol. 1993, 25, 152–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stépanoff, C.; Marchina, C.; Fossier, C.; Bureau, N. Animal Autonomy and Intermittent Coexistences: North Asian Modes of Herding. Curr. Anthropol. 2017, 58, 57–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingold, T. The Perception of the Environment; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2000; ISBN 9788578110796. [Google Scholar]

- Joks, S.; Østmo, L.; Law, J. Verbing Meahcci: Living Sámi Lands. Sociol. Rev. 2020, 68, 305–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barthel, S.; Folke, C.; Colding, J. Social-Ecological Memory in Urban Gardens-Retaining the Capacity for Management of Ecosystem Services. Glob. Environ. Change 2010, 20, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C.; Hahn, T.; Olsson, P.; Norberg, J. Adaptive Governance of Social-Ecological Systems. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2005, 30, 441–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Olsson, P.; Gunderson, L.H.; Carpenter, S.R.; Ryan, P.; Lebel, L.; Folke, C.; Holling, C.S. Shooting the Rapids: Navigating Transitions to Adaptive Governance of Social-Ecological Systems. Ecol. Soc. 2006, 11, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Urquiza Gómez, A.; Cadenas, H. Sistemas Socio-Ecológicos: Elementos Teóricos y Conceptuales Para La Discusión En Torno a Vulnerabilidad Hídrica. L’Ordin. Am. 2015, 218, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Despret, V.; Meuret, M. Cosmoecological Sheep and the Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet. Environ. Humanit. 2016, 8, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hunn, E.S.; Johnson, D.R.; Russell, P.N.; Thornton, T.F. Huna Tlingit Traditional Environmental Knowledge, Conservation, and the Management of a “Wilderness” Park. Curr. Anthropol. 2003, 44, S79–S103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armesto, J.J.; Manuschevich, D.; Mora, A.; Smith-Ramirez, C.; Rozzi, R.; Abarzúa, A.M.; Marquet, P.A. From the Holocene to the Anthropocene: A Historical Framework for Land Cover Change in Southwestern South America in the Past 15,000 Years. Land Use Policy 2010, 27, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, T. Landowners and Reform in Chile: The Sociedad Nacional de Agricultura 1919–1940; University of Illinois Press: Champaign, IL, USA, 1983; ISBN 0018-2168. [Google Scholar]

- Root-Bernstein, M. L’ange Gabriel Dans La Forêt Du Centre Du Chili. Proj. Paysage 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falabella, F. Prehistoria en Chile: Desde sus Primeros Habitantes Hasta Los Incas; Editorial Universitaria: Santiago, Chile, 2016; ISBN 9561125137. [Google Scholar]

- Molina, G.I. Saggio Sulla Storia Naturale Del Chili; Stamperia Di S. Tommaso d’Aquino: Bologna, Italy, 1782. [Google Scholar]

- Marín, J.C.; Spotorno, A.E.; González, B.A.; Bonacic, C.; Wheeler, J.C.; Casey, C.S.; Bruford, M.W.; Palma, R.E.; Poulin, E. Mitochondrial DNA Variation and Systematics of the Guanaco (Lama guanicoe, Artiodactyla: Camelidae). J. Mammal. 2008, 89, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marin, J.C.; González, B.A.; Poulin, E.; Casey, C.S.; Johnson, W.E. The Influence of the Arid Andean High Plateau on the Phylogeography and Population Genetics of Guanaco (Lama guanicoe) in South America. Mol. Ecol. 2013, 22, 463–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Murray, W. From Dependency to Reform and Back Again: The Chilean Peasantry during the Twentieth Century. J. Peasant Stud. 2002, 29, 190–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayol, A.; Rosenkranz, C.A.; Ortiz, C.A. El Chile Profundo: Modelos Culturales de La Desigualdad y Sus Resistencias; Liberalia Ediciones Ltd.: Santiago, Chile, 2013; ISBN 9568484299. [Google Scholar]

- Di Giminiani, P. Entrepreneurs in the Making: Indigenous Entrepreneurship and the Governance of Hope in Chile. Lat. Am. Caribb. Ethn. Stud. 2018, 13, 259–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Root-Bernstein, M.; Vargas, B.H.; Bondoux, A.; Guerrero-Gatica, M.; Zorondo-Rodríguez, F.; Huerta, M.; Valenzuela, R.; Bello, Á.V. Silvopastoralism, Local Ecological Knowledge and Woodland Trajectories in a Category V-Type Management Area. Biodivers. Conserv. 2022, 31, 543–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Root-Bernstein, M. Tacit Working Models of Human Behavioural Change I: Implementation of Conservation Projects. Ambio 2020, 49, 1639–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowman, D.M.J.S.; Moreira-Muñoz, A.; Kolden, C.A.; Chávez, R.O.; Muñoz, A.A.; Salinas, F.; González-Reyes, Á.; Rocco, R.; de la Barrera, F.; Williamson, G.J. Human–Environmental Drivers and Impacts of the Globally Extreme 2017 Chilean Fires. Ambio 2019, 48, 350–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garreaud, R.D.; Alvarez-Garreton, C.; Barichivich, J.; Boisier, J.P.; Christie, D.; Galleguillos, M.; LeQuesne, C.; McPhee, J.; Zambrano-Bigiarini, M. The 2010–2015 Megadrought in Central Chile: Impacts on Regional Hydroclimate and Vegetation. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2017, 21, 6307–6327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. CENSO 2017 Memoria; Ministerio de Economía, Fomento y Turismo: Santiago, Chile, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Newing, H.; Eagle, C.M.; Puri, R.K.; Watson, C.W. Conducting Research in Conservation. A Social Science Perspective; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2011; ISBN 9780415457910. [Google Scholar]

- Biggs, R.; de Vos, A.; Preiser, R.; Clements, H.; Maciejewski, K.; Schlüter, M. The Routledge Handbook of Research Methods for Social-Ecological Systems; OAPEN Foundation: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2021; ISBN 9781000401516. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN. Guidelines for Reintroductions and Other Conservation Translocations; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Root-Bernstein, M.; Bondoux, A.; Guerrero-Gatica, M.; Zorondo-Rodriguez, F. Tacit Working Models of Human Behavioural Change II: Farmers’ Folk Theories of Conservation Programme Design. Ambio 2020, 49, 1658–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narayan, T.; Sherub, S.; Root-Bernstein, M. A Culturally Appropriate Redesign of the Roles of Protected Areas and Community Conservation: Understanding the Features of the Wangchuck Centennial National Park, Bhutan. Biodivers. Conserv. 2022, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CNIL. Commission Nationale de l’Informatique et Des Libertés. Raport 2018. 2018. Available online: https://www.cnil.fr/sites/default/files/atoms/files/cnil-39e_rapport_annuel_2018.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2022).

- Di Giminiani, P.; Fonck, M. Emerging Landscapes of Private Conservation: Enclosure and Mediation in Southern Chilean Protected Areas. Geoforum 2018, 97, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Gatica, M.; Root-Bernstein, M. Challenges and Limitations for Scaling up to a Rewilding Project: Scientific Knowledge, Best Practice, and Risk. Biodiversity 2019, 20, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putman, R.; Flueck, W.T. Intraspecific Variation in Biology and Ecology of Deer: Magnitude and Causation. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2011, 51, 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barton, J.R.; Krellenberg, K.; Harris, J.M. Collaborative Governance and the Challenges of Participatory Climate Change Adaptation Planning in Santiago de Chile. Clim. Dev. 2015, 7, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyanedel, R.; Marín, A.; Castilla, J.C.; Gelcich, S. Establishing Marine Protected Areas through Bottom-up Processes: Insights from Two Contrasting Initiatives in Chile. Aquat. Conserv. 2016, 26, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovejoy, T.E. Large Herbivore Loss Threatens Biodiversity. Sci. Adv. 2015, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzini, F.; Relva, M.A.; Malizia, L.R. Impacts of Domestic Cattle on Forest and Woody Ecosystems in Southern South America. Plant Ecol. 2018, 219, 913–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Df | Sum Squares | Mean of Squares | F Value | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grasslands | 1 | 4.432 | 4.432 | 3.426 | 0.0765 |

| Shrub habitats | 1 | 11.699 | 11.699 | 11.699 | 0.0061 |

| Espinals | 1 | 6.393 | 6.393 | 4.942 | 0.0359 |

| High mountains | 1 | 7.963 | 7.963 | 6.155 | 0.0205 |

| Low mountains | 1 | 7.681 | 7.681 | 5.937 | 0.0226 |

| Central Chile | 1 | 0.329 | 0.329 | 0.254 | 0.6189 |

| Residuals | 24 | 31.051 | 1.294 |

| Df | Sum of Squares | Mean of Squares | F Value | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural outcomes | 1 | 2.50 | 2.496 | 1.592 | 0.217 |

| Daily life outcomes | 1 | 9.55 | 9.549 | 6.092 | 0.020 |

| Residuals | 28 | 43.89 | 1.568 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guerrero-Gatica, M.; Reyes, T.E.; Rochefort, B.S.; Fernández, J.; Elorrieta, A.; Root-Bernstein, M. Local Territorial Practices Inform Co-Production of a Rewilding Project in the Chilean Andes. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5966. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15075966

Guerrero-Gatica M, Reyes TE, Rochefort BS, Fernández J, Elorrieta A, Root-Bernstein M. Local Territorial Practices Inform Co-Production of a Rewilding Project in the Chilean Andes. Sustainability. 2023; 15(7):5966. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15075966

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuerrero-Gatica, Matías, Tamara Escobar Reyes, Benjamín Silva Rochefort, Josefina Fernández, Andoni Elorrieta, and Meredith Root-Bernstein. 2023. "Local Territorial Practices Inform Co-Production of a Rewilding Project in the Chilean Andes" Sustainability 15, no. 7: 5966. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15075966

APA StyleGuerrero-Gatica, M., Reyes, T. E., Rochefort, B. S., Fernández, J., Elorrieta, A., & Root-Bernstein, M. (2023). Local Territorial Practices Inform Co-Production of a Rewilding Project in the Chilean Andes. Sustainability, 15(7), 5966. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15075966