The Nonlinear Relationship between Intellectual Property Protection and Farmers’ Entrepreneurship: An Empirical Analysis Based on CHFS Data

Abstract

:1. Introduction

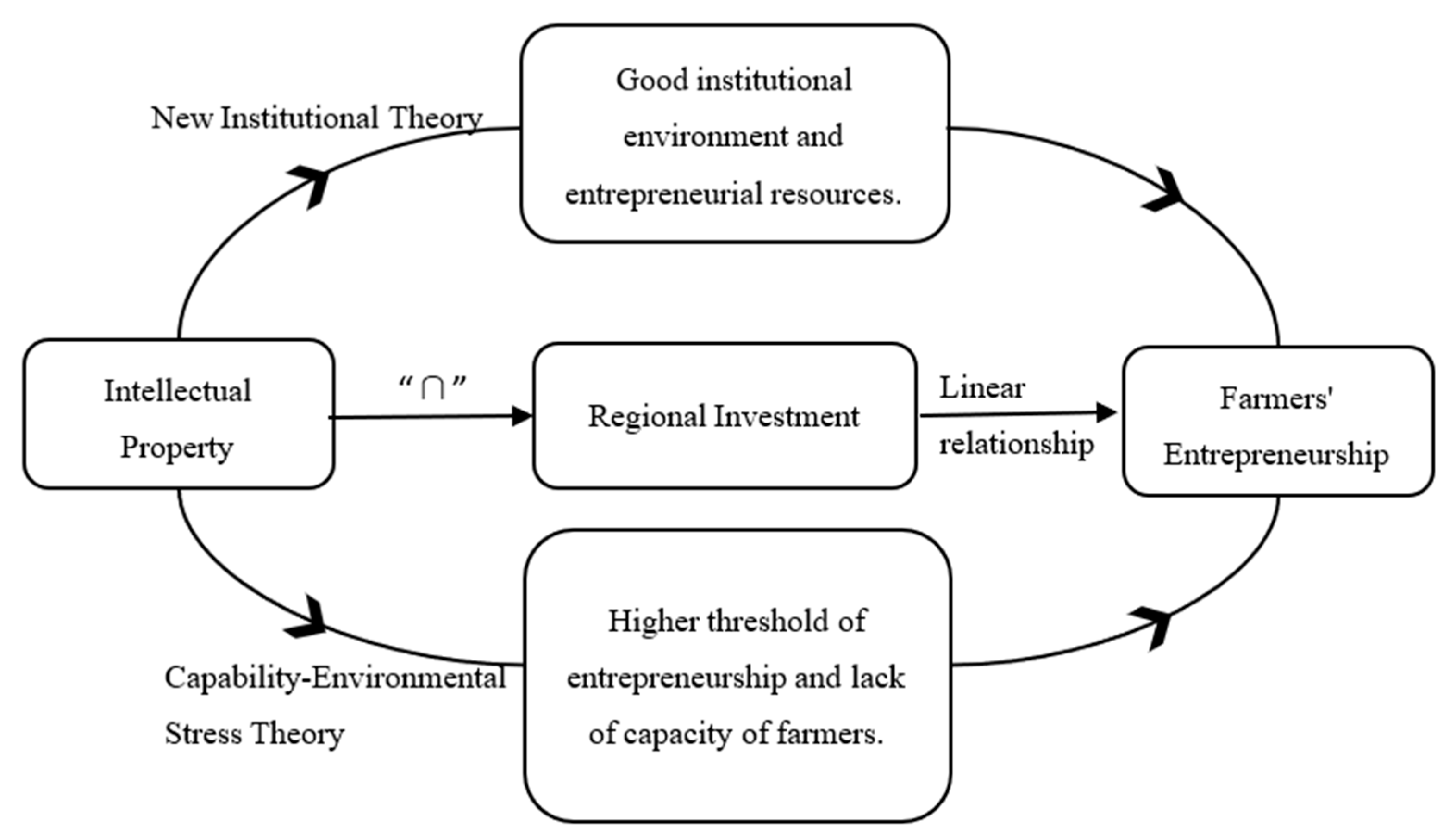

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

2.1. Direct Effect of Intellectual Property Protection and Farmer Entrepreneurship

2.2. Indirect Effects of IP Protection and Farmer Entrepreneurship: The Role of Regional Investment

3. Data Source and Model Setting

3.1. Data Sources

3.2. Model Setting

3.3. Variable Selection and Descriptive Statistics

3.3.1. Explained Variables

3.3.2. Explanatory Variables

3.3.3. Intermediary Variable: Number of Regional Investments

3.3.4. Control Variables

4. Analysis of Empirical Results

4.1. Impact of Intellectual Property Protection on Farm Household Entrepreneurship

4.2. Endogenous Processing

4.3. Robustness Tests

4.3.1. Substitution Variables

4.3.2. Delete Some Samples

4.3.3. Replacement Database

4.4. Intermediary Mechanism Test

5. Further Analyses

5.1. Heterogeneity Analysis of Farmers’ Entrepreneurship Types

5.2. Impact of IPR Protection on Farmers’ Entrepreneurial Performance

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

6.1. Research Findings

6.2. Policy Recommendations

6.3. Shortcomings and Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, T. Institutional environments and entrepreneurial start-ups: An international study. Manag. Decis. 2021, 59, 1929–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.; Liu, Z.; Gao, Z.; Wen, Q.; Geng, X. Consumer preferences for agricultural product brands in an E-commerce environment. Agribusiness. 2022, 38, 312–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustina, L.; Utami, D.A.; Wicaksono, P. The role of cognitive skills, non-cognitive skills, and internet use on entrepreneurs’ success in Indonesia. J. Econ. 2020, 16, 130–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H. Digital Inclusive Finance, Multidimensional Education, and Farmers’ Entrepreneurial Behavior. Math. Probl. Eng. 2021, 2021, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.S.; Stevenson, R.M.; O’Boyle, E.H.; Seibert, S. What matters more for entrepreneurship success? A meta-analysis comparing general mental ability and emotional intelligence in entrepreneurial settings. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2021, 15, 352–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vladasel, T.; Lindquist, M.J.; Sol, J.; van Praag, M. On the origins of entrepreneurship: Evidence from sibling correlations. J. Bus. Ventur. 2021, 36, 106017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribas, R.P. Liquidity constraints, Spillovers and Entrepreneurship: Evidence from a cash transfer program. Small Bus. Econ. 2020, 55, 1131–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xie, C.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, Q. How digital business penetration influences farmers’ sense of economic gain: The role of farmers’ entrepreneurial orientation and market responsiveness. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 187744–187753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. Agricultural Subsidies and Rural Family Entrepreneurship—Empirical Analysis Based on Chinese Microdata. Am. J. Ind. Bus. Manag. 2018, 8, 963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bu, D.; Liao, Y. Land property rights and rural enterprise growth: Evidence from land titling reform in China. J. Dev. Econ. 2022, 157, 102853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarachuk, K.; Miler-Behr, M. Is ultra-Broadland Enough? The Relationship between High-Speed internet an entrepreneurship in Brandenburg. Int. J. Technol. 2020, 11, 1103–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndubisi, N.O. Entrepreneurship and service innovation. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2014, 29, 449–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laplume, A.O.; Pathak, S.; Xavier-Oliveira, E. The politics of intellectual property rights regimes: An empirical study of new technology use in entrepreneurship. Technovation 2014, 34, 807–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, S.; Muralidharan, E. A two-staged approach to technology entrepreneurship: Differential effects of intellectual property rights. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2020, 10, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Q.; Su, J. A perfect couple? Institutional theory and entrepreneurship research. Chin. Manag. Stud. 2019, 13, 616–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbano, D.; Audretsch, D.; Aparicio, S.; Noguera, M. Does entrepreneurial activity matter for economic growth in developing countries? The role of the institutional environment. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2020, 16, 1065–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazali, E.M.; Mutum, D.S.; Javadi, H.H. The impact of the institutional environment and experience on social entrepreneurship: A multi-group analysis. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2021, 27, 1329–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Kellermanns, F.W.; Jin, L. Between-and within-person consequences of daily entrepreneurial stressors on discrete emotions in entrepreneurs: The moderating role of personality. Stress. Health 2022, 38, 568–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Meng, J.; Ling, Y.; Liao, M.; Cao, M. Localisation economies, intellectual property rights protection and entrepreneurship in China: A Bayesian analysis of multi-level spatial correlation. Struct. Chang. Econ. D. 2022, 61, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardi, C.D.; Pedrini, M. Entrepreneurial behaviour: Getting eco-drunk by feeling environmental passion. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 256, 120367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mickiewicz, T.; Rebmann, A. Entrepreneurship as trust. Found. Trends Entrep. 2020, 16, 244–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugur, M. Intellectual property protection, innovation, and knowledge diffusion. In Elgar Encyclopedia on the Economics of Knowledge and Innovation; Antonelli, C., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2022; pp. 264–270. [Google Scholar]

- Mikalef, P.; Boura, M.; Lekakos, G.; Krogstie, J. Big data analytics capabilities and innovation: The mediating role of dynamic capabilities and moderating effect of the environment. Brit. J. Manag. 2019, 30, 272–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.F.; Pan, C.; Xue, R.; Yang, X.T.; Wang, C.; Ji, X.Z.; Shan, Y.L. Corporate innovation and environmental investment: The moderating role of institutional environment. Adv. Clim. Chang. Res. 2020, 11, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaelani, A.K.; Handayani, I.; Karjoko, L. Development of tourism based on geographic indication towards to welfare state. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 29, 1227–1234. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, G.B.; Huang, X.J. The impact of city-level intellectual property protection on foreign investment introduction by Chinese firms. Financ. Trade Econ. 2019, 40, 143–157. [Google Scholar]

- Gurry, F.; Fink, C.; Khan, M.; Bergquist, K.; Lamb, R.; Feuvre, B.L.; Zhou, H. World Intellectual Property Indicators 2018; WIPO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Reis, D.; Moura, F.; Aragão, I. Entrepreneurship, intellectual property and innovation ecosystems. Int. J. Innov. Educ. Res. 2021, 9, 108–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, U. Entrepreneurs’ mental health and well-being: A review and research agenda. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 32, 290–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- He, J.; Nazari, M.; Zhang, Y.; Cai, N. Opportunity-based entrepreneurship and environmental quality of sustainable development: A resource and institutional perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 256, 120390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, R.; Rubinstein, Y. Smart and illicit: Who becomes an entrepreneur and do they earn more? Q. J. Econ. 2017, 132, 963–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Variable Name | Number of Samples | Average Value | Definition | Minimum Value | Maximum Value | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurial behavior | 6758 | 0.0886 | 1 means start-up, 0 means no start-up | 0 | 1 | 0.284 |

| Intellectual Property Protection | 6758 | 0.725 | The ratio of the number of intellectual property cases to the ratio of regional GDP | 0.01 | 5.977 | 0.930 |

| Age | 6758 | 58.15 | Age of head of household | 17 | 97 | 11.90 |

| Gender | 6758 | 0.801 | 1 for male, 0 for female | 0 | 1 | 0.400 |

| Marriage Status | 6758 | 0.955 | 1 means married, 0 means unmarried | 0 | 1 | 0.207 |

| Years of education | 6758 | 6.873 | Years of education | 0 | 19 | 3.533 |

| Physical Condition | 6758 | 2.906 | Self-assessed health status (very healthy = 1, healthy = 2, relatively healthy = 3, average = 4, unhealthy = 5) | 1 | 5 | 1.043 |

| Old-age insurance | 6758 | 0.770 | Whether to participate in pension insurance (Yes = 1, No = 0) | 0 | 1 | 0.421 |

| Medical Insurance | 6758 | 0.938 | Whether to participate in health insurance (Yes = 1, No = 0) | 0 | 1 | 0.241 |

| Homeownership | 6758 | 0.927 | 1 means own property, 0 means no own property | 0 | 1 | 0.260 |

| Family size | 6758 | 2.681 | Number of people in the respondent’s household | 1 | 12 | 1.414 |

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probit | OLS | |||||

| Intellectual Property Protection | 0.1279 ** (0.0562) | 0.1471 *** (0.0589) | 0.1589 *** (0.0593) | 0.0208 ** (0.0089) | 0.0242 *** (0.0090) | 0.0254 *** (0.0089) |

| Intellectual Property Squared | −0.0239 * (0.0137) | −0.0264 * (0.0144) | −0.0289 ** (0.0145) | −0.0037 * (0.0021) | −0.0042 ** (0.0003) | −0.0045 ** (0.0021) |

| Age | −0.0175 *** (0.0019) | −0.0149 *** (0.0021) | −0.0027 *** (0.0106) | −0.0024 *** (0.0003) | ||

| Gender | 0.0233 *** (0.0649) | 0.2071 *** (0.0655) | 0.0271 *** (0.0077) | 0.0237 *** (0.0077) | ||

| Marriage Status | 0.3479 *** (0.1277) | 0.2519 * (0.1289) | 0.0458 *** (0.0134) | 0.0365 *** (0.0137) | ||

| Years of education | 0.0285 *** (0.0073) | 0.0287 *** (0.0075) | 0.0036 *** (0.0010) | 0.0035 *** (0.0010) | ||

| Physical Condition | −0.1277 *** (0.0223) | −0.1279 *** (0.0224) | −0.0192 (0.0033) | −0.0193 *** (0.0033) | ||

| Old-age insurance | −0.0611 (0.0524) | −0.0119 (0.0084) | ||||

| Medical Insurance | 0.1875 * (0.1042) | 0.0202 * (0.0123) | ||||

| Owned Housing | 0.1253 (0.0983) | 0.0082 (0.0109) | ||||

| Family size | 0.0939 *** (0.0159) | 0.0103 *** (0.0027) | ||||

| Constants | −1.2458 ** (0.0507) | −0.7058 *** (0.1874) | −1.2166 *** (0.2244) | 0.1083 ** (0.0094) | 0.2173 *** (0.0258) | 0.1724 *** (0.0302) |

| Year and city fixed effects | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Number of samples | 6758 | 6758 | 6758 | 6758 | 6758 | 6758 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.0057 | 0.0591 | 0.0696 | 0.0037 | 0.0334 | 0.0364 |

| Variable | IV-Probit | 2SLS |

|---|---|---|

| Intellectual Property Protection | 0.8219 *** (0.1503) | 0.1330 *** (0.0263) |

| Intellectual Property Protection Squared | −0.1788 *** (0.0353) | −0.0286 *** (0.0058) |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.8742 | 0.8743 |

| Phase I F-value | 4270 | 1830.33 |

| Tool variable T value | 36.31 | 51.27 |

| Wald test | 24.51 (0.0000) | 257.93 (0.0000) |

| DWH test Chi2 | - | 20.66 (0.0000) |

| Underidentification test | - | 333.159 |

| p-value | - | 0.0000 |

| Wald-F | - | 1318.69 |

| KP Wald-F | - | 594.29 |

| Control variables | Control | Control |

| Year and city fixed effects | Control | Control |

| Data volume | 6758 | 6758 |

| Variables | (7) | (8) | (9) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Farmers’ Entrepreneurship | Farmers’ Entrepreneurship | Farmers’ Entrepreneurship | |

| Intellectual Property | 0.1136 *** (0.0229) | 0.2653 *** (0.0739) | 0.3976 *** (0.1428) |

| Intellectual Property Squared | −0.2970 *** (0.0874) | −0.0466 *** (0.0180) | −0.0896 ** (0.0436) |

| Control variables | Control | Control | Control |

| Year and city fixed effects | Control | Control | Control |

| _cons | −0.9319 *** (0.2699) | −1.7836 *** (0.2384) | −1.5526 *** (0.2763) |

| N | 6758 | 3575 | 2878 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.0791 | 0.0327 | 0.0707 |

| Variables | (10) Farmers’ Entrepreneurship | (11) Foreign Investment | (12) Farmers’ Entrepreneurship |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intellectual Property Protection | 0.1589 *** (0.0593) | 0.5163 *** (0.0217) | 0.1583 ** (0.0649) |

| Intellectual Property Protection Squared | −0.0289 ** (0.0145) | −0.0769 *** (0.0049) | −0.0280 * (0.0147) |

| Number of inward investment | 0.1051 *** (0.0402) | ||

| Constant term | −1.2166 *** (0.2244) | 3.5624 *** (0.0825) | −1.7812 *** (0.2753) |

| Control variables | Control | Control | Control |

| Year and city fixed effects | Control | Control | Control |

| N | 6758 | 6758 | 6758 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.0696 | 0.1308 | 0.0659 |

| Variables | (13) Opportunistic Entrepreneurship | (14) Proactive Entrepreneurship |

|---|---|---|

| Intellectual Property | 0.2586 *** | −0.0538 |

| (0.0704) | (0.0771) | |

| Intellectual Property Squared | −0.0464 *** | 0.0075 |

| (0.0177) | (0.0176) | |

| _cons | −1.5687 *** | 1.8834 *** |

| (0.2793) | (0.3039) | |

| Control variables | Control | Control |

| Year and city fixed effects | Control | Control |

| N | 6758 | 6758 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.0866 | 0.0292 |

| Variables | (15) Entrepreneurial Performance |

|---|---|

| Intellectual Property Protection | 0.3188 *** (0.0799) |

| Constant term | 9.5913 *** (0.8188) |

| Control variables | Control |

| Year and city fixed effects | Control |

| N | 6758 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.0350 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, X.; Zheng, Y.; Yu, W. The Nonlinear Relationship between Intellectual Property Protection and Farmers’ Entrepreneurship: An Empirical Analysis Based on CHFS Data. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6071. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15076071

Liu X, Zheng Y, Yu W. The Nonlinear Relationship between Intellectual Property Protection and Farmers’ Entrepreneurship: An Empirical Analysis Based on CHFS Data. Sustainability. 2023; 15(7):6071. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15076071

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Xinmin, Yue Zheng, and Wencheng Yu. 2023. "The Nonlinear Relationship between Intellectual Property Protection and Farmers’ Entrepreneurship: An Empirical Analysis Based on CHFS Data" Sustainability 15, no. 7: 6071. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15076071