Educational Donors’ Expectations and Their Outcomes in the COVID-19 Era: The Moderating Role of Motivation during Sequential Evaluation Phases

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Background

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Measures

4. Results

5. Discussion

- The relationship between prior expectations (T1) and attitudes toward educational donations (T3), which had been focused on only as a conceptual idea in prior research, is positive on a longitudinal basis. Similarly, the relationships between prior expectations and the expectation of satisfaction (T2) and between the expectation of satisfaction (T2) and attitudes toward educational donations (T3) are also positive during subsequent educational donation events.

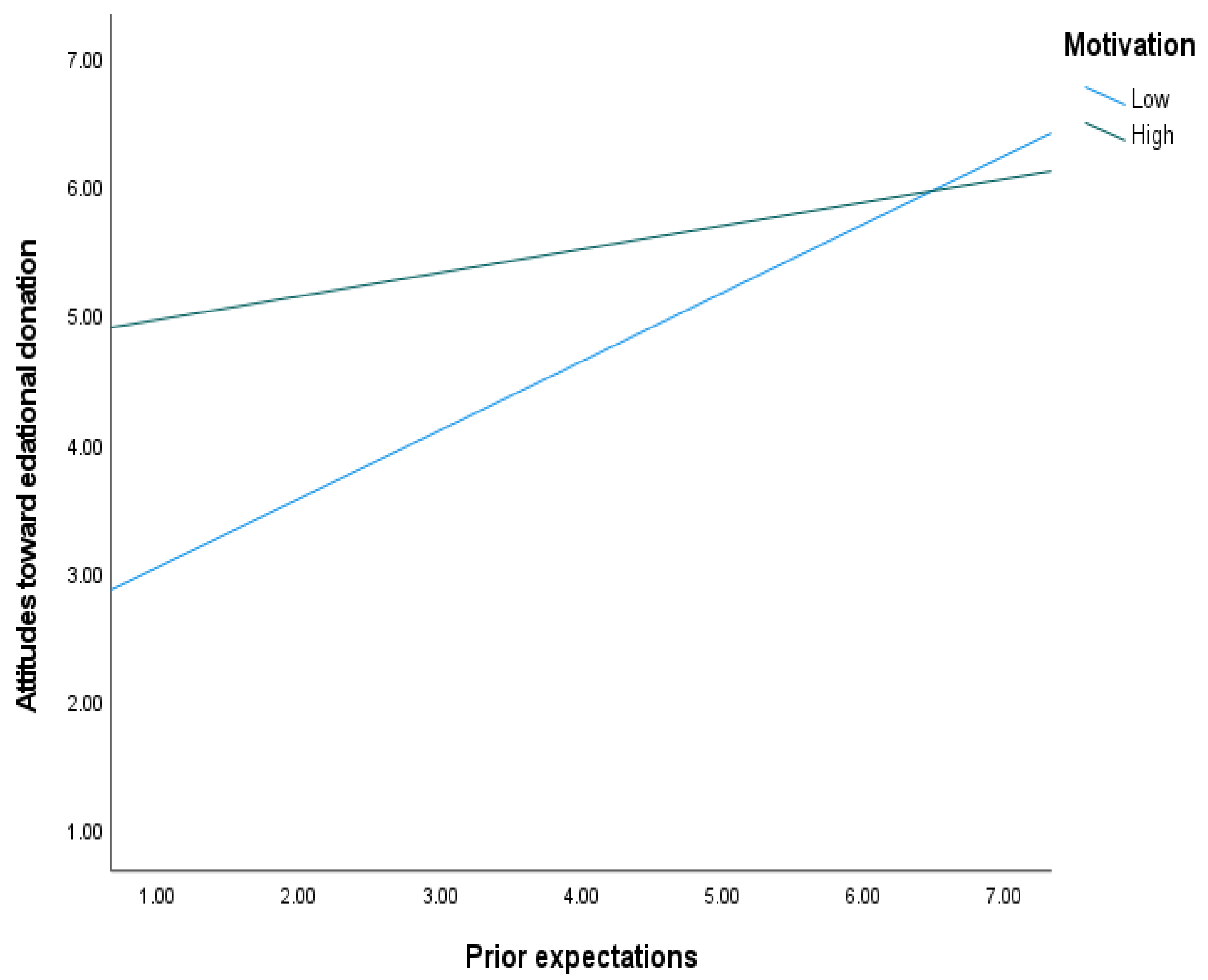

- While the linkage between prior expectations and attitudes toward educational donations is negatively moderated by the role of donor motivation, the moderator does not control the relationship between the expectation of satisfaction and attitudes toward educational donations.

- Even if prior expectations are low, if the donors’ motivation to participate in educational donations is high, their attitudes toward educational donations are more favorable than those of donors who are less motivated to participate in educational donations. However, even when motivation is low, if prior expectations gradually increase, their attitudes become favorable more rapidly than those of donors with high motivation.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gorst, J.; Kanji, G.; Wallace, W. Providing customer satisfaction. Total Qual. Manag. 1998, 9, 4–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.; Gursoy, D. Employee satisfaction, customer satisfaction, and financial performance: An empirical examination. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rust, R.T.; Oliver, R.L. Should we delight the customer? J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2000, 28, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwanka, R.J.; Buff, C. COVID-19 generation: A conceptual framework of the consumer behavioral shifts to be caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2021, 33, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Ha, H. An empirical test of educational donors’ satisfaction level in donating for education before and after the COVID-19 era. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. A cognitive model for the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction. J. Mark. Res. 1980, 17, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, V.; Kumar, P.; Tsiros, M. Attribute-level performance, satisfaction, and behavioral intentions over time: A consumption-system approach. J. Mark. 1999, 63, 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valvi, A.C.; West, D.C. E-loyalty is not all about trust, price also matters: Extending expectation-confirmation theory in bookselling websites. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2013, 14, 99–123. [Google Scholar]

- Li, A.; Rosenblum, A.M.; Nevis, I.F.; Garg, A.X. Adolescent classroom education on knowledge and attitudes about deceased organ donation: A systematic review. Pediatr. Transplant. 2013, 17, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abderrahman, B.H.; Saleh, M. Investigating knowledge and attitudes of blood donors and barriers concerning blood donation in Jordan. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 116, 2146–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tontus, H.O. Educate, re-educate, then re-educate: Organ donation-centered attitudes should be established in society. Transplant. Proc. 2020, 52, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Suh, Y. Why do users switch to a disruptive technology? An empirical study based on expectation-disconfirmation theory. Inf. Manag. 2014, 51, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carraher-Wolverton, C. The co-evolution of remote work and expectations in a COVID-10 world utilizing an expectation disconfirmation theory lens. J. Syst. Inf. Technol. 2022, 24, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, H.; John, D.; John, J.; Kim, N. The critical role of marketer’s information provision in temporal changes of expectations and attitudes. J. Consum. Mark. 2013, 30, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, C.J.; Norman, P.; Alganem, S.; Conner, M. Expectations are more predictive of behavior than behavioral intentions: Evidence from two prospective studies. Ann. Behav. Med. 2015, 49, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, M.D.; Herrmann, A.; Huber, F. The evolution of loyalty intentions. J. Mark. 2006, 70, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pincus, J. The consequences of unmet needs: The evolving role of motivation in consumer research. J. Consum. Behav. 2004, 3, 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, I.; Habel, J.; Jia, M.; Wei, S. Consumer stockpiling under the impact of a global disaster: The evolution of affective and cognitive motives. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 142, 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Yang, K.; Min, J.; White, B. Hope, fear, and consumer behavioral change amid COVID-19: Application of protection motivation theory. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2022, 46, 558–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohli, S.; Timelin, B.; Fabius, V.; Veranen, M. How COVID-19 Is Changing Consumer Behavior: Now and Forever. McKinsey Company Report. 2020. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/~{}/media/mckinsey/industries/retail/our%20insights/how%20covid%2019%20is%20changing%20consumer%20behavior%20now%20and%20forever/how-covid-19-is-changing-consumerbehaviornow-and-forever.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2022).

- Homburg, C.; Koschate, N.; Hoyer, W.D. The role of cognitive and affect in the formation of customer satisfaction: A dynamic perspective. J. Mark. 2006, 70, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Satisfaction: A Behavioral Perspective on the Consumer; M.E. Sharpe: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Y.; La, S. What influences the relationship between customer satisfaction and repurchase intention? Investigating the effects of adjusted expectations and customer loyalty. Psychol. Mark. 2004, 21, 351–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Lekhawipat, W. How customer expectations become adjusted after purchase. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2016, 20, 443–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H.; Chaiken, S. The Psychology of Attitudes; Harcourt College Publishing: Fort Worth, TX, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, M.T.; Cohen, J.B.; Pracejus, J.W.; Hughes, G.D. Affect monitoring and the primacy of feelings in judgment. J. Consum. Res. 2001, 28, 167–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wohlfeil, M.; Whelan, S. Consumer motivations to participate in event-marketing strategies. J. Mark. Manag. 2006, 22, 643–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, P. Emotional aspects of decision behavior: A comparison of explanation concepts. Eur. Adv. Consum. Res. 1995, 2, 246–250. [Google Scholar]

- Hus, C.H.C.; Cai, L.A.; Li, M. Expectation, motivation, and attitude: A tourist behavioral model. J. Travel Res. 2010, 49, 282–296. [Google Scholar]

- Happ, E.; Hofmann, V.; Schnitzer, M. A look at the present and future: The power of emotions in the interplay between motivation, expectation and attitude in long-distance hikers. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 19, 100527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, J.M.; Johnson, M.E.; Twynam, G.D. Volunteer motivation, satisfaction, and management at an elite sporting competition. J. Sport. Manag. 1998, 12, 288–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Reisinger, Y.; Kim, M.J.; Yoon, S. The influence of volunteer motivation on satisfaction, attitudes, and support for a mega-event. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 40, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millette, V.; Gagné, M. Designing volunteers’ tasks to maximize motivation, satisfaction and performance: The impact of job characteristics on volunteer engagement. Motiv. Emot. 2008, 32, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, J.E.; Kotrlik, J.W.; Higgins, C.C. Organizational research: Determining appropriate sample size in survey research. Inf. Technol. Learn. Perform. J. 2001, 19, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, I.A.; Dioko, L. Understanding the mediated moderation role of customer expectations in the customer satisfaction model: The case of casinos. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindenberg, S.; Steg, L. Normative, gain, and hedonic goal frames guiding environmental behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2007, 63, 117–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zyminkowska, K.; Perek-Bialas, J.; Humenny, G. The effect of product category on customer motivation for customer engagement behavior. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2023, 47, 299–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, D.E.; Wright, R.T. Shut-up I don’t care: Understanding the role of relevance and interactivity on customer attitudes toward repetitive online advertising. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2008, 9, 62–76. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.S.; Hershberger, S.L. Assessing context validity and content equivalence using structural equation modeling. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 2002, 9, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babin, B.J.; Svensson, G. Structural equation modeling in social science research: Issues of validity and reliability in the research process. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2012, 24, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Henseler, J. Bridging design and behavioral research with variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Advert. 2017, 46, 178–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F.; Scharkow, M. The relative trustworthiness of inferential tests of the indirect effect in statistical mediation analysis: Does method really matter? Psychol. Sci. 2013, 24, 1918–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F.; Rockwood, N.J. Regression-based statistical mediation and moderation analysis in clinical research: Observations, recommendations, and implementation. Behav. Res. Ther. 2017, 98, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overwalle, F.V.; Siebler, F. A connectionist model of attitude formation and change. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2005, 9, 231–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scale Items | Loading | AVE |

|---|---|---|

| Prior expectations (T1) (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.83; CR = 0.90) I expect the program to motivate me to participate. I expect the program to be useful to students. How successful do you expect the program to be, overall? Expectation of satisfaction (T2) (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.78; CR = 0.90) I am overall satisfied with the educational donation program.To what extent did the overall performance of the educational donation program meet your expectations? Donor motivations (T2) (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.86; CR = 92) Program enjoyment. Helping students develop their talents. Gaining self-esteem. Attitude toward educational donation (T3) (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.80; CR = 88) Bad/Good | 0.74 0.83 0.78 0.79 0.82 0.91 0.80 0.77 0.76 | 0.61 0.64 0.68 0.62 |

| Dislike/Like Unfavorable/Favorable | 0.74 0.87 |

| Mean (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fornell–Larcker Criteria | |||||

| 1. Prior expectations | 5.11 (1.31) | 0.61 | |||

| 2. Expectations of satisfaction | 5.21 (1.38) | 0.32 | 0.64 | ||

| 3. Donor motivation | 5.49 (1.28) | 0.27 | 0.28 | 0.68 | |

| 4. Attitudes | 5.48 (1.34) | 0.40 | 0.44 | 0.42 | 0.62 |

| Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) | |||||

| 1. Prior expectations | |||||

| 2. Expectations of satisfaction | 0.38 | ||||

| 3. Donor motivation | 0.31 | 0.34 | |||

| 4. Attitudes | 0.48 | 0.55 | 0.50 |

| Path | B | t-value | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior expectations—satisfaction (H1) | 0.64 | 3.47 ** | 0.2722 | 1.0055 |

| Prior expectation—attitudes (H2) | 0.88 | 4.78 ** | 0.5199 | 1.2473 |

| Satisfaction—attitudes (H3) | 0.46 | 2.78 ** | 0.1348 | 0.7893 |

| Prior expectations × Motivation (H4) | −0.25 | −0.21 * | −0.4888 | −0.0173 |

| Prior expectations × satisfaction (H5) | −0.12 | −0.09 (ns) | −0.3379 | 0.0973 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pan, H.; Ha, H.-Y. Educational Donors’ Expectations and Their Outcomes in the COVID-19 Era: The Moderating Role of Motivation during Sequential Evaluation Phases. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6249. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15076249

Pan H, Ha H-Y. Educational Donors’ Expectations and Their Outcomes in the COVID-19 Era: The Moderating Role of Motivation during Sequential Evaluation Phases. Sustainability. 2023; 15(7):6249. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15076249

Chicago/Turabian StylePan, Huifeng, and Hong-Youl Ha. 2023. "Educational Donors’ Expectations and Their Outcomes in the COVID-19 Era: The Moderating Role of Motivation during Sequential Evaluation Phases" Sustainability 15, no. 7: 6249. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15076249

APA StylePan, H., & Ha, H.-Y. (2023). Educational Donors’ Expectations and Their Outcomes in the COVID-19 Era: The Moderating Role of Motivation during Sequential Evaluation Phases. Sustainability, 15(7), 6249. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15076249