Determinants of Perceived Performance during Telework: Evidence from Romania

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Contextualization

2.2. Telework and Work Performance

3. Conceptual Model and Hypotheses

- Employees’ motivation;

- Employees’ dependence on coordination by a superior;

- Employees’ self-organizing ability;

- Stress perceived by an employee.

4. Summary of Research Design

Research Instruments, Data Selection and Analysis

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

5.2. Evaluation of the Model Fitness

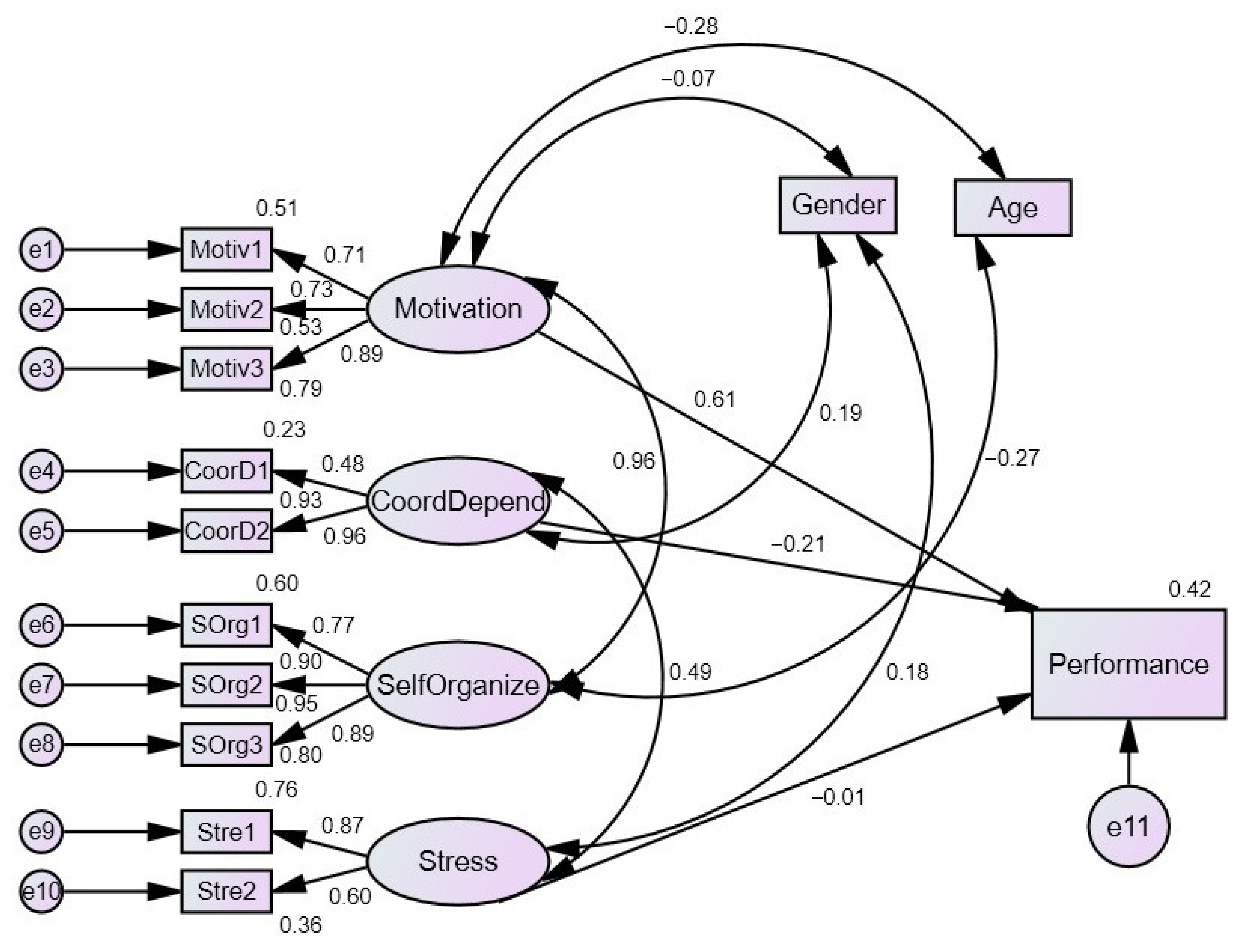

5.3. Structural Equations Modelling

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

7.1. Recommendations

- Capitalize on teleworking situations by better elaborating on everything related to the job description in order to increase motivation; employees are motivated by novelty, variety of tasks, autonomy, feedback, etc. [59].

- Know the aspirations of teleworkers, develop coherent strategies and transparent policies for the promotion and development of one’s career within telework.

- Develop policies and strategies in order to ensure a good work-life balance, starting from the investigation of factors that can have a negative influence in this respect.

- Develop practices and to offer tools that contribute to better communication between employees and superiors, between colleagues and collaborators.

- Train managers and employees for a better adaptation to telework conditions.

- Develop policies and strategies aimed at encouraging autonomous work and improving self-organization abilities.

7.2. Implications

7.3. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- López-Igual, P.; Rodríguez-Modroño, P. Who is teleworking and where from? Exploring the main determinants of telework in Europe. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, C.L. A Review of Telework in the COVID-19 Pandemic: Lessons Learned for Work-Life Balance? COVID 2022, 2, 1405–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingel, J.I.; Neiman, B. How many jobs can be done at home? J. Public Econ. 2020, 189, 104235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sostero, M.; Milasi, S.; Hurley, J.; Fernández-Macías, E.; Bisello, M. Teleworkability and the COVID-19 Crisis: A New Digital Divide? JRC121193. Seville 2020, European Commission. Available online: https://joint-research-centre.ec.europa.eu/publications/teleworkability-and-covid-19-crisis-new-digital-divide_en (accessed on 27 May 2022).

- Roman, T. Educația superioară în vremea on-line-ului de urgență. In Abordări și Studii de Caz Relevante Orivind Managementul Organizațiilor din România, în Contextul Pandemiei COVID-19; Nicolescu, O., Popa, I., Dumitrașcu, D., Eds.; Editura Pro Universitaria: București, Romania, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Neculăesei, A.N. De la criza generată de pandemia COVID-19, la reinventare în managementul resurselor umane. In Abordări și Studii de Caz Relevante Orivind Managementul Organizațiilor din România, în Contextul Socio-economic Complex Influențat de Pandemia COVID-19, Digitalizare și Trecerea la Economia Bazată pe Cunoștințe; Nicolescu, O., Popa, I., Dumitrașcu, D., Eds.; Editura Pro Universitaria: București, Romania, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 27 May 2022).

- Beauregard, T.A.; Basile, K.A.; Canónico, E. Telework: Outcomes and facilitators for employees. In The Cambridge Handbook of Technology and Employee Behavior; Landers, R.N., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 511–543. Available online: https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/28079/ (accessed on 27 May 2022).

- Gálvez, A.; Tirado, F.; Martínez, M.J. Work–life balance, organizations and social sustainability: Analyzing female telework in Spain. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbaz, S.; Richards, J.B.; Provost Savard, Y. Teleworking and work–life balance during the COVID-19 pandemic: A scoping review. Can. Psychol. Psychol. Can. 2022. advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raišienė, H.; Tummers, L.; Bekkers, V. The benefits of teleworking in the public sector: Reality or rhetoric? Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2019, 39, 570–593. [Google Scholar]

- Cannito, M.; Scavarda, A. Childcare and Remote Work during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Ideal Worker Model, Parenthood and Gender Inequalities in Italy. Ital. Sociol. Rev. 2020, 10, 801–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meunier, S.; Bouchard, L.; Coulombe, S.; Doucerain, M.; Pacheco, T.; Auger, E. The association between perceived stress, psychological distress, and job performance during the COVID-19 pandemic: The buffering role of health-promoting management practices. Trends Psychol. 2022, 30, 549–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, S.; Barrios, A. Teleworking and technostress: Early consequences of a COVID-19 lockdown. Cogn. Technol. Work 2022, 24, 441–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoica, A.; Cosma, A.; Tudor, A.; Țoc, L.A.; Petre, A. COVID-19 pandemic and the employees experience: Motivation of the staff within an event organizing company. Manager 2020, 32, 130–137. [Google Scholar]

- Raišienė, A.G.; Rapuano, V.; Dőry, T.; Varkulevičiūtė, K. Does telework work? Gauging challenges of telecommuting to adapt to a “new normal”. Hum. Technol. 2021, 17, 126. [Google Scholar]

- Blahopoulou, J.; Ortiz-Bonnin, S.; Montañez-Juan, M.; Torrens Espinosa, G.; García-Buades, M.E. Telework satisfaction, wellbeing and performance in the digital era. Lessons learned during COVID-19 lockdown in Spain. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 41, 2507–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Athanasiadou, C.; Theriou, G. Telework: Systematic literature review and future research agenda. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, C.; Golding, S.E.; Yarker, J.; Lewis, R.; Ratcliffe, E.; Munir, F.; Windlinger, L. Future teleworking inclinations post-COVID-19: Examining the role of teleworking conditions and perceived productivity. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 863197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrușa, A.L.; Butoi, E. Approaching telework system by Romanian employees in the Pandemic Crisis. Ecoforum J. 2022, 11, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Fana, M.; Milasi, S.; Napierala, J.; Fernández-Macías, E.; Vázquez, I.G. Telework, Work Organisation and Job Quality during the COVID-19 Crisis: A Qualitative Study (No. 2020/11); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020; p. JRC122591. Available online: https://joint-research-centre.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2020-11/jrc122591.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2022).

- Turkeș, M.C.; Stăncioiu, A.F.; Băltescu, C.A. Telework during the COVID-19 Pandemic—An Approach from the Perspective of Romanian Enterprises. Amfiteatru Econ. 2021, 23, 700–717. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade, C.; Petiz Lousã, E. Telework and work–family conflict during COVID-19 lockdown in Portugal: The influence of job-related factors. Adm. Sci. 2021, 11, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Subramony, M. Understanding the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on teleworkers’ experiences of perceived threat and professional isolation: The moderating role of friendship. Stress Health 2022. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikunaga, K.; Nakata, A.; Kuwamura, M.; Odagami, K.; Mafune, K.; Ando, H.; Fujino, Y. Psychological Distress, Japanese Teleworkers, and Supervisor Support During COVID-19. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2023, 65, e68–e73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, S.; Huang, Y.; Chang, C.H.D. Supporting interdependent telework employees: A moderated-mediation model linking daily COVID-19 task setbacks to next-day work withdrawal. J. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 105, 1408–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novianti, K.R.; Roz, K. Teleworking and workload balance on job satisfaction: Indonesian public sector workers during COVID-19 pandemic. APMBA 2020, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Golden, T. Telework and the Navigation of Work-Home Boundaries. Organ. Dyn. 2021, 50, 100822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, C.L. The experience of teleworking with dogs and cats in the United States during COVID-19. Animals 2021, 11, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moens, E.; Lippens, L.; Sterkens, P.; Weytjens, J.; Baert, S. The COVID-19 crisis and telework: A research survey on experiences, expectations and hopes. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2022, 23, 729–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Yu, M.C.; Marin, S. Exploring public sentiment on enforced remote work during COVID-19. J. Appl. Psychol. 2021, 106, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufman, G.; Taniguchi, H. Working from Home and Changes in Work Characteristics during COVID-19. Socius 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sava, J.A. Remote work frequency before and after COVID-19 in the United States. Statista 2022. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1122987/change-in-remote-work-trends-after-covid-in-usa/ (accessed on 27 May 2022).

- Milasi, S.; González-Vázquez, I.; Fernández-Macías, E. Telework in the EU before and after the COVID-19: Where We Were, Where We Head to Headlines; European Union, Joint Research Centre: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2020; Available online: https://joint-research-centre.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2021-06/jrc120945_policy_brief_-_covid_and_telework_final.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2022).

- Eurostat. Rise in EU Population Working from Home. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/-/ddn-20221108-1#:~:text=The%20impact%20of%20the%20COVID,13.5%25%20(%2B1.2%20pp) (accessed on 27 May 2022).

- Vasilescu, C. The Impact of Teleworking and Digital Work on Workers and Society. Annex VII—Case Study on Romania. Study Requested by the EMPL Committee. 2021. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/66a175dc-ae7b-11eb-9767-01aa75ed71a1/language-en/format-PDF/source-search (accessed on 27 May 2022).

- Eurofound. Working during COVID-19. 2021. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/data/covid-19/working-teleworking (accessed on 27 May 2022).

- Parker, K.; Horowitz, J.M.; Minkin, R. COVID-19 Pandemic Continues to Reshape Work in America; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2022/02/16/covid-19-pandemic-continues-to-reshape-work-in-america/ (accessed on 27 May 2022).

- Eurofound. Living, Working and COVID-19; COVID-19 series; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020; p. 33. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/sites/default/files/ef_publication/field_ef_document/ef20059en.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2022).

- Lund, R. Researching crisis—Recognizing the unsettling experience of emotions. Emot. Space Soc. 2012, 5, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D. Thinking, Fast and Slow; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Paulus, D.; Fathi, R.; Fiedrich, F.; de Walle, B.V.; Comes, T. On the interplay of data and cognitive bias in crisis information management: An exploratory study on epidemic response. Inf. Syst. Front. 2022, 1–25. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10796-022-10241-0 (accessed on 27 May 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moroń, M.; Biolik-Moroń, M. Trait emotional intelligence and emotional experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak in Poland: A daily diary study. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 168, 110348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renström, E.A.; Bäck, H. Emotions during the COVID-19 pandemic: Fear, anxiety, and anger as mediators between threats and policy support and political actions. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2021, 51, 861–877. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/jasp.12806 (accessed on 27 May 2022). [CrossRef]

- Schelhorn, I.; Schlüter, S.; Paintner, K.; Shiban, Y.; Lugo, R.; Meyer, M.; Sütterlin, S. Emotions and emotion up-regulation during the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Xue, C.; Cheng, Y.; Lim, E.T.; Tan, C.W. Understanding work experience in epidemic-induced telecommuting: The roles of misfit, reactance, and collaborative technologies. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 154, 113330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindler, J. How to Watch for Bias during Crisis, Forbes. 2020. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbescoachescouncil/2020/09/09/how-to-watch-for-bias-during-crisis/ (accessed on 27 May 2022).

- Moglia, M.; Hopkins, J.; Bardoel, A. Telework, hybrid work and the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals: Towards policy coherence. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionescu, C.A.; Fülöp, M.T.; Topor, D.I.; Duică, M.C.; Stanescu, S.G.; Florea, N.V.; Coman, M.D. Sustainability Analysis, Implications, and Effects of the Teleworking System in Romania. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoian, C.A.; Caraiani, C.; Anica-Popa, I.F.; Dascălu, C.; Lungu, C.I. Telework Systematic Model Design for the Future of Work. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boston Consulting Group. BCG Digital Maturity Global Study. Available online: https://media-publications.bcg.com/BCGX-mind-the-tech-gap.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2022).

- COM. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, The Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions 2030 Digital Compass: The European way for the Digital Decade; Document 52021DC0118; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52021DC0118 (accessed on 27 May 2022).

- Allen, T.D.; Golden, T.D.; Shockley, K.M. How effective is telecommuting? Assessing the status of our scientific findings. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2015, 16, 40–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, M. The (not so simple) case for teleworking: A study at Lloyd’s of London. New Technol. Work Employ. 2005, 20, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illegems, V.; Verbeke, A. Telework: What does it mean for management? Long Range Plan. 2004, 37, 319–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böll, S.; Cecez-Kecmanovic, D.; Campbell, J. Telework and the nature of work: An assessment of different aspects of work and the role of technology. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS) 2014, Tel Aviv, Israel, 9–11 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Parliament of Romania. Law No. 81/2018 of 30 March 2018, on the Regulation of Telework Activity. Official Gazette No. 296 of 2 April 2018. Available online: https://static.anaf.ro/static/10/Anaf/legislatie/L_81_2018.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2022).

- Hackman, J.R.; Oldham, G.R. Motivation through the design of work: Test of a theory. Organ. Behav. Human Perform. 1976, 16, 250–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackman, J.R.; Pearce, J.L.; Wolfe, J.C. Effects of changes in job characteristics on work attitudes and behaviors: A naturally occurring quasi-experiment. Organ. Behav. Human Perform. 1978, 21, 289–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerasoli, C.P.; Nicklin, J.M.; Ford, M.T. Intrinsic motivation and extrinsic incentives jointly predict performance: A 40-year meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2014, 140, 980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, K.A. Transformational leadership and employee psychological well-being: A review and directions for future research. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalleberg, A.L.; Nesheim, T.; Olsen, K.M. Is participation good or bad for workers? Effects of autonomy, consultation and teamwork on stress among workers in Norway. Acta Sociol. 2009, 52, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Yperen, N.W.; Wörtler, B.; De Jonge, K.M. Workers’ intrinsic work motivation when job demands are high: The role of need for autonomy and perceived opportunity for blended working. Comput. Human Behav. 2016, 60, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earl-Wilcox, K.A. Autonomy and Engagement as Intrinsic Motivation Factors for Remote Workers. Ph.D. Dissertation, Grand Canyon University, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Petrova, K. Empirical investigation of autonomy and motivation. Int. J. Humanit. Social Sci. 2011, 1, 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Hamouche, S.; Parent-Lamarche, A. Teleworkers’ job performance: A study examining the role of age as an important diversity component of companies’ workforce. J. Organ. Eff. People Perform. 2022. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, T.S.H.; Lim, V.K.G. Factorial dimensions and differential effects of gender on perceptions of teleworking. Women Manag. Rev. 1998, 13, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 3rd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, E.J.; Harrington, K.M.; Clark, S.L.; Miller, M.W. Sample size requirements for structural equation models: An evaluation of power, bias, and solution propriety. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2013, 73, 913–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sideridis, G.; Simos, P.; Papanicolaou, A.; Fletcher, J. Using structural equation modeling to assess functional connectivity in the brain: Power and sample size considerations. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2014, 74, 733–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with Amos Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 2nd ed.; Taylor and Francis Group: New York, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, R.; Chetty, P. Criteria for Reliability and Validity in SEM Analysis. Available online: https://www.projectguru.in/criteria-for-reliability-and-validity-in-sem-analysis/ (accessed on 23 January 2023).

- Asparouhov, T.; Hamaker, E.L.; Muthén, B. Dynamic structural equation models. Struct. Equ. Model. 2018, 25, 359–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2014, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Black, B.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R.; Tatham, R. Multivariate Data Analysis, 6th ed.; Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 102–111. [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum, R.C.; Browne, M.W.; Sugawara, H.M. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychol. Methods 1996, 1, 130–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, D. Structural Equation Modeling: Foundations and Extensions, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 124–133. [Google Scholar]

- Tănăsescu, R.I.; Leon, R.D. Emotional intelligence, occupational stress and job performance in the Romanian banking system: A case study approach. Manag. Dyn. Knowl. Econ. 2019, 7, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.; McDonald, C. Defining a conceptual framework for telework research. In Proceedings of the 18th Australasian Conference on Information Systems ACIS 2007, Toowoomba, Australia, 4–7 December 2007; p. 120. [Google Scholar]

| Work from Home Preference | EU 27 | Romania |

|---|---|---|

| Jun/Jul 2020 | 13.3% | 14.4% |

| Feb/Mar 2021 | 15.7% | 17.9% 1 |

| Definitions of Telework | Authors |

|---|---|

| telework as an activity which “includes all work-related substitutions of telecommunications and related information technologies for travel” | Jack Nilles, 1973, Apud Collins, 2005 [54] |

| “we define telework as paid work from home, a satellite office, a telework center or any other work station outside of the main office for at least one day per workweek” | Illegems, Verbeke, 2004, pp. 319–320 [55] |

| “telework or telecommuting describes work undertaken away from traditional offices by means of technology” | Böll et al., 2014, p. 1 [56] |

| “telecommuting is a work practice that involves members of an organization substituting a portion of their typical work hours (ranging from a few hours per week to nearly full-time) to work away from a central workplace—typically principally from home—using technology to interact with others as needed to conduct work tasks” | Allen et al., 2015, p. 44 [53] |

| “telework (remote work, telecommuting, flexible work, virtual work) is a work practice that involves working away from the corporate office for a portion of the work week, typically from home, and using technology as needed to conduct work” | Golden, 2021, p. 1 [28] |

| “the form of work organization through which the employee, regularly and voluntarily, fulfills his attributions specific to the position, occupation, or profession he holds, in another place than the work organized by the employer, at least one day a month, using information and communication technology” | Law No. 81/2018 of 30 March 2018, Romania Article no. 2/a [57] |

| Gender | Frequency | Percent | Education | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masculine | 58 | 26.5 | High school | 19 | 8.7 |

| Feminine | 161 | 73.5 | Other | 5 | 2.3 |

| Age | Frequency | Percent | Bachelor | 84 | 38.4 |

| Under 25 years | 111 | 50.7 | Master | 101 | 46.1 |

| 26–35 years | 50 | 22.8 | PhD | 10 | 4.6 |

| 36–45 years | 33 | 15.1 | Company size | Frequency | Percent |

| 46–55 years | 24 | 11 | Between 1–9 employees | 34 | 15.5 |

| Over 56 years | 1 | 0.5 | Between 10–49 employees | 60 | 27.4 |

| Field of work | Frequency | Percent | Between 50–99 employees | 29 | 13.2 |

| Agriculture | 2 | 0.9 | Between 100–249 employees | 19 | 8.7 |

| Industry | 3 | 1.4 | Over 250 employees | 77 | 35.2 |

| Services | 59 | 26.9 | Seniority on position | Frequency | Percent |

| Retail sales | 19 | 8.7 | Under 1 year | 68 | 31.1 |

| Hospitality industry | 7 | 3.2 | 1–3 years | 78 | 35.6 |

| IT | 41 | 18.7 | 3–5 years | 27 | 12.3 |

| Education | 31 | 14.6 | 5–10 years | 12 | 5.5 |

| Other | 56 | 25.6 | Over 10 years | 34 | 15.5 |

| Construct | Item | Loading | Cronbach’s Alpha | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motivation | Motiv1—The novelty of telework has pushed me to be more productive | 0.715 | 0.820 | 0.824 | 0.612 |

| Motiv2—I think that the prospects of my future career are better when I telework | 0.729 | ||||

| Motiv3—I think that telework ensures a better work-life balance, which positively influences the quality and quantity of the work performed | 0.890 | ||||

| Coordination dependence (CoordDepend) | CoorD1—The chief’s support is important to perform the tasks well | 0.488 | 0.631 | 0.712 | 0.577 |

| CoorD2—It is important that the boss give me clear indications about what I have to do to have good performance during telework | 0.957 | ||||

| Self-organization (SelfOrganize) | SOrg1—The time I wasted in traffic was better used during telework | 0.774 | 0.902 | 0.907 | 0.765 |

| SOrg2—The comfort of home helped me/helps me work better and more efficiently | 0.948 | ||||

| SOrg3—I organize my work time better when I’m home | 0.893 | ||||

| Stress | Stre1—Fear that I will lose my job made me work more during telework | 0.875 | 0.688 | 0.713 | 0.563 |

| Stre2—Fear of the virus affected/affects my work | 0.600 |

| Hypothesis | Relationship | Estimate | Acceptance or Rejection of the Hypothesis |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Motivation → Performance | 0.612 *** 1 | Accept (Major impact) |

| 2 | CoordDepend → Performance | −0.205 ** | Accept (Minor-Medium impact) |

| 3 | Stress → Performance | −0.021 | Reject (Non-significant) |

| 4 | CoordDepend ↔ Stress | 0.490 *** | Accept (Moderate relationship) |

| 5 | Motivation ↔ SelfOrganize | 0.960 *** | Accept (Very strong relationship) |

| Parameter | Estimation Approach | |

|---|---|---|

| ML | Bayesian | |

| Motiv1 ← Motivation | 0.853 | 0.860 |

| Motiv2 ← Motivation | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Motiv3 ← Motivation | 1.296 | 1.300 |

| CoorD1 ← CoordDepend | 0.430 | 0.428 |

| CoorD2 ← CoordDepend | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| SOrg1 ← SelfOrganizing | 0.717 | 0.716 |

| SOrg2 ← SelfOrganizing | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| SOrg3 ← SelfOrganizing | 1.016 | 1.017 |

| Stre1 ← Stress | 1.510 | 1.532 |

| Stre2 ← Stress | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Performance ← Motivation | 0.723 | 0.726 |

| Performance ← CoordDepend | −0.170 | −0.170 |

| Performance ← Stress | −0.021 | −0.026 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Neculaesei, A.N.; Tocar, S. Determinants of Perceived Performance during Telework: Evidence from Romania. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6334. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086334

Neculaesei AN, Tocar S. Determinants of Perceived Performance during Telework: Evidence from Romania. Sustainability. 2023; 15(8):6334. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086334

Chicago/Turabian StyleNeculaesei, Angelica Nicoleta, and Sebastian Tocar. 2023. "Determinants of Perceived Performance during Telework: Evidence from Romania" Sustainability 15, no. 8: 6334. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086334

APA StyleNeculaesei, A. N., & Tocar, S. (2023). Determinants of Perceived Performance during Telework: Evidence from Romania. Sustainability, 15(8), 6334. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086334