1. Introduction

Urbanists, geographers, and planners consider placemaking a basic, primordial human activity. Thus, Relph [

1] depicted making places as necessary for the well-being of the individual and the society, while Tuan [

2] promoted the idea that a sense of place is an innate quality and a necessary component of human interaction. However, in planning and policy-making, placemaking is a relatively young approach [

3,

4,

5] that offers tools and methods for changing and redesigning public spaces from the bottom up, based on the needs and aspirations of residents, businesses, and owners. In the last twenty years, placemaking has become popular in North America, where it is often presented as an approach to building urban communities, and improving social and economic urban metrics; from there, it has spread throughout the world of planning [

6,

7,

8].

Researching and evaluating placemaking is as new as the field itself. On the one hand, the literature enumerates many benefits of placemaking for the city, considering social values of local identity, sense of belonging to the public space and increased interaction between residents living around a shared geographical area and economic values, such as creating jobs and attracting investments [

4,

9,

10]. On the other hand, the starting point of many papers is the absence of an inherent definition, methodology and setup for placemaking processes [

11,

12,

13,

14], which may lead to confusion [

14,

15]. This paper therefore offers a few principles that would anchor theoretical discussions of placemaking despite the inherent lack of conceptual framework, which is its merit. We do that by developing a simple typology that can help examine complete placemaking initiatives, as well as specific actions included in these processes, and evaluate their sincereness and motivations. We thus aim to contribute to the existing literature dealing with placemaking.

Placemaking was born as a critique of traditional, rigid planning carried out by the establishment and those in power. Its popularity lies in the opportunity to produce a relevant, informal alternative to planning, one that considers people’s needs and observes the feasible options in place. In a way, the absence of an agreed work process is a key part of placemaking’s philosophy [

13,

16]. The active parties are free to adapt the pace and characteristics of each project to the specific case [

5,

7], and formulate a case-sensitive planning and implementation process.

The present study adopts a critical viewpoint for evaluating the actual practice(s) evolving under the placemaking umbrella. By examining the adoption of community placemaking in Israel, and analyzing the motives and performance of the parties involved, including developers, funders and participants, we offer a typology of projects. The various community placemaking types are differentiate by the dynamics resulting from specific combinations of participants. They also serve as a warning sign of possible exploitation of processes with loose boundaries and deviations from the inclusive community ideal.

The research is based on community placemaking projects in Beersheba and Yeroham, in southern Israel, and a few small projects in these cities. We start with a concise introduction of the literature on place, placemaking and implementing placemaking. After a note on methodology and a short description of the study area, we present our findings. Focusing on the relationships between actors, we portray four models of placemaking, positioned around two main axes: the goal axis, which ranges from a broad community goal to a narrow, predetermined aim, and the motivation axis, ranging from internal to external motivation. We designate the resulting four types of placemaking: “traditional”, “governmental”, “artistic-economic” and “segregative”. Thus, despite defining all of projects under consideration as community placemaking, each model depicts a different form with specific relationships between the participants. Application of these models has far-reaching practical implications for planned space and the ability to realize the community goal, which is defined as the primary goal.

1.1. Place and Placemaking

The literature of geography puts a specific emphasis on the term “place”. In addition to encompassing the intimate relations between the individual’s identity, discursive habits and immediate environment, the place is considered responsible for sociocultural links and creating a sense of belonging within a community [

17,

18]. The lack of a sense of place is also discussed. Relph [

1] uses “placeless” to describe the standardization of places created by top-down planning and duplication, while missing locally-bound characteristics. Placelessness blocks the emergence of authenticity, the emotional link to a place, and eventually harms the creation of community.

The temptation to produce placeless places is enormous. In the age of globalization, when culture becomes a consumer product, detached from its original context, one can find urban spaces dedicated to tourism and shopping, offering homogeneous, unrelated experiences [

19]. Despite their lack of identity, such places are defined as “active urban space”. People visit them massively; time and money are spent on them. And yet, these places cannot produce authenticity, a sense of belonging or help build a community [

20]. These detached urban places are the opposite of to what [

18] defines a “place of plurality”: one with uniqueness, history and meanings, a place that is significant for varied people, activities and contexts. Castello’s claim overlaps with the central purpose of placemaking, which aims to strengthen authenticity and thus enhance the connection between people and space. Significantly, modern planning and rapidly evolving urban spaces stress the role of place as an “urban glue” that creates communities [

17,

21].

In the mid-1990s, the term “placemaking” became widespread, although its roots go back to the 1960s when the awareness of good urbanism’s characteristics started to increase in North America [

22]. The placemaking approach has evolved as an alternative to modern planning, referring to both process and purpose. In terms of process, placemaking seeks to skip over statutory planning stages and focus on concrete, relatively rapid changes in the built environment. Regarding purpose, placemaking is not targeted toward spatial development but seeks to enhance vibrant community spirit. As part of this, placemaking deals with the transformation of “standard” places into places that enhance the population living in their vicinity and serves it in a unique, coordinated manner [

16,

23].

The idea of placemaking rests on Jane Jacobs’ [

24] critique of modern design. In her view, urban planning has led to the destruction of functional urban spaces by producing standard, alienated places that prevent personal connections. Alongside the critique, Jacobs lists the values that planning should use, including diversity, density, and connectivity [

25]. The appropriate tools are broad, designed to enhance the experience of visiting the place, and differentiate it from other places by stimulating the senses of sight, smell, hearing, taste and touch. The current paper adopts the notion of placemaking as focused on planning and actions conducted in the public realm to heighten feelings of communal experience anchored in the place [

7,

17,

26]. In addition, we relate to the use of artistic methods and elements that form creative placemaking [

6,

8,

13], thus enhancing visitors’ attachment and experience of the place. The more powerful the place, the more different it is from other places without being disconnect from its surroundings, the better it serves the community.

1.2. Implementing Placemaking: The Role of NGOs and Professional Placemakers

Community development in North American cities began in the 1960s at the initiative of NGOs [

27]. In the mid-1980s, Drabek [

28] stated that the challenge for NGOs is to provide an alternative to global development and free themselves from funders’ interests. Community-based organizations have proven their ability to generate political capital, technical know-how and a whole network of inter-organizational ties. Many organizations have emerged to promote urban revitalization in the midst of significant economic and social decline. It is not necessarily a matter of protest and resistance but rather mobilizing for concrete action, such as the massive improvement of public spaces as a catalyst for the economic and social resurgence. Such actions contribute to the interests of the communities in which they operate [

11,

29].

In the 1980s, NGOs became an important force in democratic civil society. Their roles included decision-making processes, human rights protection, critique of government functioning, and providing services. Their success stems from understanding that the state is limited in its ability to represent and promote diverse needs and social groups. Gradually, these organizations expanded from the local level to the national and international spheres [

14,

30]. Placemaking has become a leading tool for NGOs seeking an unconventional way to support the communities they represent and introduce an alternative to formal and institutional planning [

31,

32].

The challenges facing placemaking projects relate to the lack of an accepted definition and the incompatible expectations of residents, participants and managers regarding the process and product. There is often a need to overcome disagreement between funding bodies, artists and creators recruited for the project, and the residents, because of their differing visions for the project. Difficulty in understanding the needs of the place can be an obstacle. Projects may also encounter difficulties recruiting collaborators because of the community’s or the leaders’ skepticism about the place’s identity and the target audience [

12,

13,

23]. Another challenge relates to the role played by professional placemakers, especially artists, in placemaking projects. Bain and Landau [

33] warn that such professionals, hired by municipalities and financers, tend to responsibilize themselves or their employees to articulate place narratives for the community rather than with them. This assignment of responsibilities is not necessarily conscious or intended but nonetheless results from the loose, case-based methodological framework.

The practice of placemaking was brought to Israel from North America by Jewish organizations such as the Jewish Agency and the Jewish Federations of North America. It soon became widespread in the public, non-profit, and private sectors [

32]. In recent years, companies and entrepreneurs, who specialize in placemaking and offer services for building communities and improving urban spaces, have sprung up (for example [

34]). Considering the lack of agreed principles for evaluating placemaking, this paper contributes a theoretical outline that would serve scholars and practitioners. The subject of this research is the variety of implications and relationships between the active organizations and participating communities that emerge from their identities (insiders/outsiders) and goals (broad, community-oriented, or specific and aesthetic).

2. Methodology

The research asks: which types of relationships between funders, professional planners, municipal authorities and community delegates drive the implementation of placemaking projects? To answer this, we applied a qualitative method based on in-depth interviews with involved parties: philanthropists (funders), initiators, artists and participants. In 2018 we investigated several placemaking initiatives in Beersheba and Yeroham, two cities located at the northern Negev in Israel [

35,

36]. We conducted 16 in-depth interviews with placemaking funders’ representatives (5 interviewees), placemaking entrepreneurs from municipalities and associations (9 interviewees) and independent artists (2 interviewees). Details are listed in the

Appendix A. Interviewees were selected in a snowball method, starting with funders’ representatives then moving to placemakers and artists. All interviewees were asked about their motivation and the participants with whom they engaged, the project’s goals in their and other participants’ eyes, and the decisions that affected the project’s outcomes. We then applied critical discourse analysis to expose the participants’ perceptions and experiences, and categorized the subjects, attitudes toward placemaking, and participants’ assertions and reactions. We chose 4 projects representing each placemaking type that were articulated based on our analysis, and highlighted the important and representative charachteristics of each type.

Beersheba and Yeroham are located in the northern Negev, a semi-arid peripheral area in Israel’s southern district. Beersheba, designated since the early 1950s as the Negev’s capital and later Israel’s southern metropolis, developed in ’pulses’ of massive governmental planning and housing construction. The city is now home to about 210,000 residents. In addition, the city hosts the regional governmental offices, a large hospital (Soroka Hospital) and Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, one of Israel’s largest and most prestigious universities [

35,

36]. On the other hand, besides the remote location, the city’s image is affected by the relative socio-economic weakness of its population [

38].

Yeroham, located about 45 km south-eastern of Beersheba is a development town constructed by the state in the early 1950s. The town’s population counts around 10,000 people. Besides the poor image of a development town, Yeroham’s image suffers from it’s remote location and relatively weak socio-economic level [

38].

3. Findings

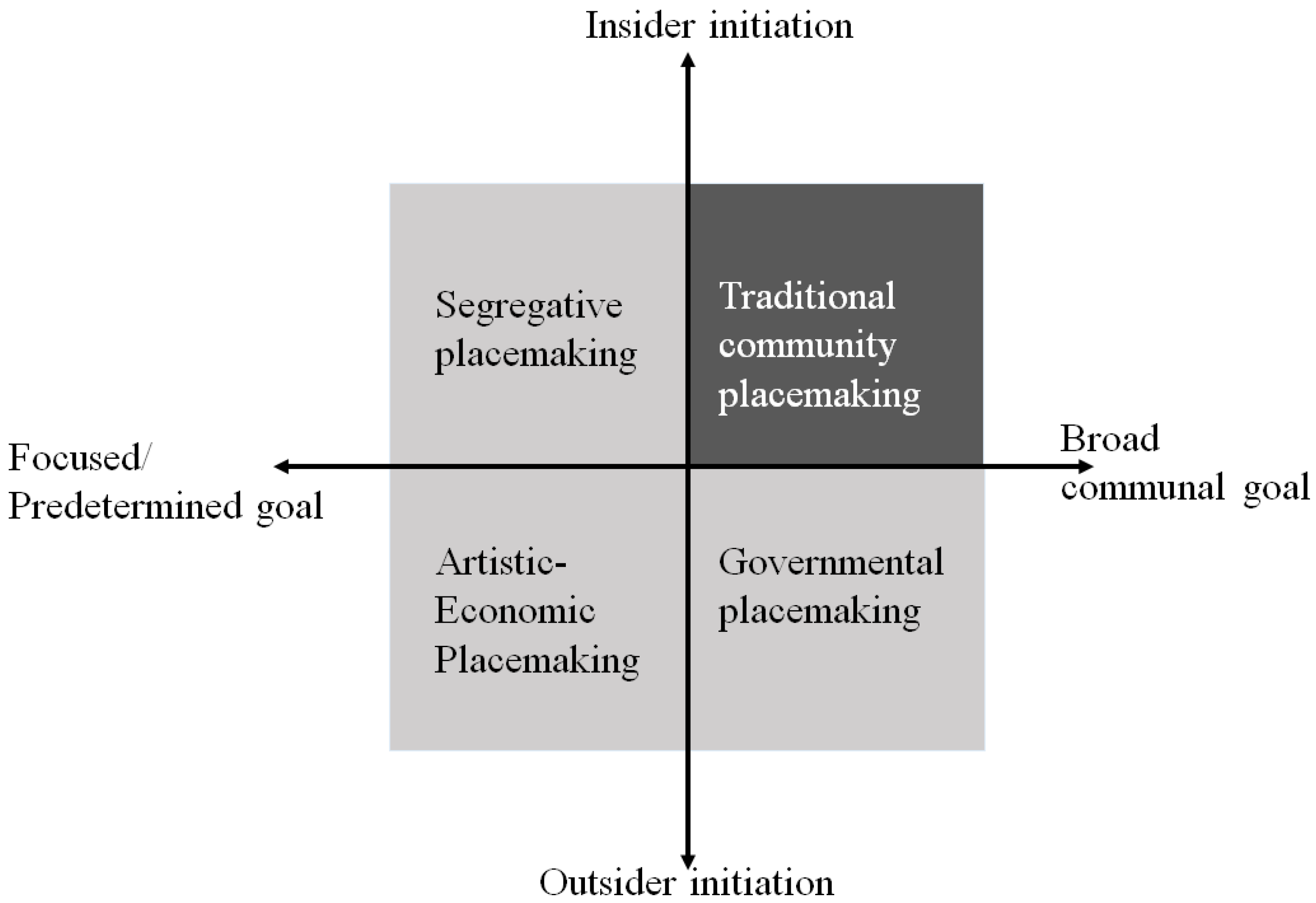

The interviewees’ responses and the information gathered from social networks enabled us to develop a model describing four types of placemaking organized around two axes. The themes collected from the discourse analyses related to the initiation of placemaking projects: the motivation to create them and the expectations related to them in terms of social relations. We base our models on these findings. The horizontal axis maps motivation, ranging from internal to external. Internal motivation refers to an initiator from within the community or one who recruits residents. External motivation refers to projects defined and managed by players from the outside. The vertical axis maps the type of goal, ranging from a specific, predetermined aim to inclusive, communal goals. The two axes describe four types of placemaking (

Figure 1):

We shall describe each type with the help of a representative project.

3.1. Traditional Community Placemaking: Insider Initiation with a Broad Communal Goal

This model derives directly from the theoretical framework and is the only one whose objectives rest on the actors’ full consent. This model describes a community process advocating the extensive participation of residents, the joint formation of local values and the idea of joint creation. The challenges faced in this model often stem from the difficulty of defining and agreeing on the concept of community. However, once these are resolved, the project is usually conducted in a good atmosphere.

The project representing this model is located in Ha’shaked (The Almond) neighborhood in Yeroham. The neighborhood is structured with a few open areas, “circles”, each surrounded by 13 to 26 private homes. For a long time, the open spaces were neglected, adding to the low image of the neighborhood.

The local council initiated a placemaking project in the neighborhood, focused on the circles. The council offered a sum of money for each circle whose surrounding residents set up a committee and proposed an agreed plan for its renovation. The council staff provided professional assistance, advice and materials, while the residents were expected to conduct the construction and renovation independently (

Figure 2). The placemaking project was intended to achieve a twofold goal. First, to get residents to take responsibility for their public space by designing, building and maintaining it. Second, to empower the residents, enhance social relationships and contribute to a sense of local pride. The community planner LS described it: “We wanted the circles’ residents to feel powerful and capable, and hopefully leverage this feeling for other matters when needed”.

The project is considered a success, as all circles were renovated and are well maintained to date (end of 2022). Most are used for children’s games, and include shaded sitting areas. Interviewees report that the relationship between the neighbors has been strengthened thanks to the process.

3.1.1. Process Characteristics

The model rests on full cooperation between the initiators and the residents, from developing the idea through planning and execution. This model has great potential to bring the population closer, and arouse interest and a desire to participate. Instances of opposition to the process provoke discussion and often contribute to the community’s formation and self-definition.

This model’s central value is the residents’ involvement and the gradual transfer of responsibility to their hands. The initiators saw themselves as a thread that connects the project to the residents, to help initiate it and then eventually pass it on. The development of specific public places results from the involvement of the residents along the way. Thus, LS said that placemakers—professional planners assigned by the local council—met with the residents, studied the places together and discussed matters with the participants at several consecutive meetings. The feeling was of “quiet intervention” that included informing the participants about the current stage, allowing access to information and supporting the residents’ thinking process. “We sit with notebooks, each circle at a time, and write what they [the residents] think and want. After reaching agreements on various points, we try to pass the responsibility to them”, reported LS. The central role played by the residents and their freedom to present ideas and talk about their living environment was highlighted.

Insisting on residents’ viewpoints is a central trait typifying this model. This is not necessarily an agreed baseline in placemaking projects, as reflected in an incident described by CS. She is an artist, runs an art workshop in Yeroham and was part of the circles project. She tells of a funder who asked her to implement a specific placemaking project he had conceived. The economic temptation was tremendous, but the proposal did not fit the community action model. She said:

We took a step back. They wanted to bring in a lot of money, which could have funded many of my activities, but I did not want to do something dictated to me by an outsider… Because those who sat at the round table, the school principals, the teachers and the designers who live and work here, told me: “It does not interest us. This is not a contributive action”. The donors who have big money sometimes offer irrelevant projects.

The mismatch between the financier’s approach and the communal worldview tipped the scales for CS in that project. However, such a dilemma did not exist in the circles project.

3.1.2. A Note on the Artist/Placemaker

CS related to the dynamics at the circles project, and stated her worldview:

I think successful placemaking rises from the ground and does not land from above… We hardly do placemaking based on artistic initiatives… I support initiatives that come from below, from the residents. We do not say “we want to do something in the mall” but listen to the residents’ wishes and visions.

Her worldview is to encourage residents to take action in the public space.

Regarding the artists’ role in placemaking projects, CS says: “I would not want my name in the headlines; that’s not the point. The artist is not at the center; the action is at the center”. In the current model of a community process, the artist’s attitude and treatment is a tool that serves the will of the public and not otherwise. “We only work with artists and designers who are willing to be attentive to the community, not those who dream of building the sculpture they fantasize about”. CS admits that she fights the daily pressures to use the sponsors’ logos. “I care that the products will be pleasant, of high quality and long-lasting. Even though I am an artist myself, I do not care if the artist or the funding source receives credit. That’s not the point”.

3.2. Governmental Placemaking: Outsider Initiation with a Broad Communal Goal

This model refers to a placemaking process driven by an outside entrepreneur who seeks to enhance an existing or future community. The salient feature is the lack of active public involvement in the planning and implementation of the project. At the information-gathering stage, a connection between the initiator and the residents may be established, but it is superficial and occasional. The initiators exhibit good intentions but usually make independent decisions that do not involve the residents. Whether private or public, the funder donates a generous sum and demonstrates creative thinking for building and strengthening the community, yet expects to control the process and the product.

An example of a governmental process is given through a placemaking process in Ringelblum neighborhood, Beersheba, near the Ben-Gurion University of the Negev and part of the student bubble surrounding it [

35]. In this case, the local student association initiated an ongoing event called “Making a Street”, to strengthen the relationships between the residents of the neighborhood and the students. One notable project was establishing a dog park, hoping students and residents would meet in there, get to know each other, and connect. AK, the director of the Making a Street project in the student association, said that the project converted a neglected public space in the neighborhood into a beautiful dog park, which become popular with dog owners, mostly students (

Figure 3). However, he said, “due to the inadequacy of the dog park for other residents of the neighborhood, and the many complaints received about it, we had to close the dog park three months after its launch.” Currently, “Making a Street” run a communal garden nearby.

Governmental placemaking is not necessarily a recipe for failure. Still, it is a project that meets the needs and thoughts of those operating the project, not necessarily those of the local community.

3.2.1. Process Characteristics

Governmental placemaking starts when an administrative body seeks to invest in the public space in order to achieve socio-economic goals or change the image of a place: “to create a movement in these centers and not just renovate. To see that people come, visit, stay; how we make this a place of creativity… A place where people want to be, that people are attracted to” (AK). There was goodwill; the student association wished to serve the residents and provide them with an attractive public space to promote a healthy lifestyle and community.

Still, governmental placemaking is based on detached, top-down decision-making. The first layer affected is the participation of the residents in the project’s programming. Responding to a question regarding public participation, AK of the student association replied: “First of all, there was a tour with the municipality and with guys who understand more about establishing parks in the city. Then, there are some talks with people from the place”. EL, a representative of a North American community that funded the project, among other placemaking initiatives in Beersheba, also explains: “This story of public participation is not something that has been proven essential or an ‘absolute step’ for moving forward. It sounds very undemocratic, but sometimes it is not necessary. The public need not be involved at any cost”. Both speakers did not see public participation in the process as a necessary stage.

In many cases, funding for governmental placemaking comes from external funds, for whom the governmental body must “sell” the idea. AK from the student association recounts:

I had a delegation here last year of people from Montreal, and then I said to myself, “Listen, this could be a win-win”. That is, we will support the establishment of a project we really want to erect and the guests will feel that they are contributing much more than money… The artists were there and they prepared the area and everything; all the guests (the delegation) needed to do was paint. I mean, they painted the fences with the artists in each of these centers and did other things as well, but for me, it was a win-win.

Thus, governmental placemaking is also a matter of establishing long-lasting relationships between the governmental bodies and the donors.

The representative of the donor community also has an interest in this relationship and in the placemaking that we call “governmental”. EL, the donor’s representative, confesses: “What attracts us is also our interest as a federation… Why is it important? It was important to show our donors that what we do is not detached from the community needs expressed in these projects”. The donor representative wants to show that the donation is being used to create a space that helps the community. Here, too, the community is presented schematically and is not perceived as a partner in the process.

No wonder, therefore, that AK describes the community’s response as follows: “The residents didn’t stop. They complained to the municipality, all the residents. Conversations, endless talks. They complained about noise, the dogs stirred up dust [that bothered] all the buildings. It just did not suit the neighborhood and the residents”.

3.2.2. A Note on the Artist/Placemaker

In government placemaking, the artists who design the place are also perceived of as service providers. The artists we interviewed said that the initiators—the student association or one of the associations supported by the North American donors—are the ones who determine the location and invite the artists to offer ideas. MS, a placemaker active in Beersheba, says, “The student association suggested that I submit an idea for another placemaking project. They told me where it was supposed to be and gave me a free hand to offer what I wanted. They said that there is a budget dedicated to this place”. The artistic aspect is, therefore, marginal, and the governmental goal leads the placemaking project.

3.3. Artistic-Economic Placemaking: Outsider Initiation with a Focused/Predetermined Goal

This model refers to a place-making process that is driven by two main motivations, connecting art and money. The bodies running this type of placemaking include initiators (foundations or donors who use placemaking as a communal tool) and creators (artists or designers) who hope to gain resources and reputation that will enable them to stay active in the placemaking market. The foundations wish to display their abilities and attract budgets and contributions for further actions. At the same time, the creators aim to produce an aesthetic, impressive product that represents them and illustrates their artistic ability. Either way, this type of motivation may be at odds with the community’s vision or needs. Most processes in this model are carried out by “experts” in various fields, whether activists of associations or independent creators and placemakers, and not by residents or community bodies. The resulting projects have a prominent presence in the urban space but not necessarily in the context of any social activity.

One example representing this model is the There is Here project in Yeroham, an outdoor exhibit located in the center of the city that presents photos and videos from the unique desert environment in which the city is located. The exhibition shows the Yeroham Crater on one side and Yeroham Lake on the other. It was carried out under the supervision of the local council and the auspices of the municipal economic company, and implemented by local artists.

They wanted to do a project that would be cool, that would be placed in the public space and stimulate pride… I do not think it is one hundred percent placemaking, because it is not a place that belongs to the community. This project has no local users. It serves passers-by and the general public.

This explanation, given by HM, the head of the Artists Association in Yeroham, notes the focus on the final product and the opportunity for artists to use public art under community cover, even though there is no community in place.

Another example is a project called Street Games (

Figure 4) implemented by the town’s Design Terminal in collaboration with the municipality and a private design studio. One day in April 2018, the parents of children in kindergarten were invited to come for the afternoon, and bring their children to the public park where the project is located. The purpose was to photograph children using the new games that had been installed as part of the placemaking initiative. HT, an industrial designer living in Yeroham and active in the urban Design Terminal, was also involved in the Street Games project. He explained: “It ended up being a business. People want to be paid for their project and move forward. For that matter, we provide design services and it’s our business card. We want to market it and show we are placemakers”. This is the essence of artistic-economic placemaking. It crossed the line of encouraging the making of places, and has begun marketing them. Placemaking is used to conceal hidden marketing tactics of organizations and companies seeking their next project.

3.3.1. Process Characteristics

Artistic-economic placemaking raises the question of whether any art project in the public space and carried out by donors and local authorities deserves to be called placemaking. Placemaking projects in this model are planned and implemented from top to bottom, with almost no public involvement. In the examples above, the Yeroham Council proposed to enhance community relationships by marking unique places. In the process of planning and implementation, the aim has slightly changed to stress the need to beautify the city. The involved artists and placemakers were responsible for locating and designing the projects, and selected them with minimal public involvement.

3.3.2. Professional Placemaker’s Role

The developers’ attitude towards the public is evident. This is how SS, a young artist and partner in many placemaking projects in the city, summarized her position: “Users are not part of the story. They have no influence, although they indicate the product’s success”. When asked how she defines placemaking, she replied: “I will not say ‘with residents’ the participation’ because it means nothing to me. Yes, residents are informed and can express their opinions, but they cannot decide on the results or design the project”. SS views herself as a professional, and won’t let the inhabitants replace her.

HT, another artist who participates in placemaking projects in Yeroham, recounts setting up the exhibition in the city center: “There was a public meeting, but only once, and then we’ve just gone our separate ways, went to work, developed things ourselves, entirely detached from the world”. The public meeting was important for gathering information, not for cooperation with the residents.

3.4. Segregative Placemaking: Insider Initiation with a Focused/Predetermined Goal

This model refers to applying placemaking to tighten a community’s spatial relationships and thereby, intentionally or not, leading to the repression of a population not associated with the specific group. Placemaking initiatives may help communities, knowingly or unknowingly, address the place as their own space for the use and representation of community members. A defined community’s appropriation of public space may result in spatial segregation and exclusion of other populations, communities, or individuals.

The Network (HaReshet, in Hebrew), an active community in Neighborhood B, Beersheba, is an example of segregative placemaking. The Network is an organization founded by former students of the Ben-Gurion University of the Negev with the goal of producing community initiatives, and thus encourage university graduates to stay in the city and settle there rather than leave after graduation, as most students, who come to a university from elsewhere tend to do [

36]. The Network collaborates with several actors in the city from the public and third sectors, and implements a variety of placemaking initiatives in the public space. Although, it consists of some 700 hundred young men and women scattered throughout the city, its unofficial center is Neighborhood B because many community members live there, and its commercial center, the Chen center, hosts several community initiatives.

3.4.1. Process Characteristics

MB, a resident of Neighborhood B and an activist in The Network, defines placemaking as a practice for substantial and physical public space change through institutions and individuals. She sees the activity as intended “to adjust the public space for the community’s needs and to encourage as many initiatives and diverse activities within this space as possible… Placemaking is about changing the space together with the community, more or less, in my opinion”. Indeed, the public space of Neighborhood B is replete with elements serving and presenting The Network. These include the public park with scattered seating and play areas, where the group holds yoga classes; Everything You Need (“Kolboynik”, in the local slang), a cooperative equipment warehouse located in the Chen center that lends home equipment, tools and objects; an open carpentry shop staffed by volunteers and used to repair furniture, houseware and toys; a “give-and-take” circle that allows those interested in contributing and participating in free lectures or training; Cinema Chen (

Figure 5), an open-air movie screening for children and more.

MB says that the relationship between The Network and the Beersheba municipality is good and reciprocal. She admits, however, that the community’s activities in Neighborhood B don’t always receive explicit approval from the city, with the understanding that the authorities will approve in retrospect: “Often in the past, we would wait for the municipality’s approval or budget to act, for building a bench or putting a sign. In time we learned to work. People ask, ‘How did the municipality approve it?’ Well, it isn’t always pre-approved.” The ability to take action before receiving institutional approval is made possible by the organization’s view, supported by the tacit agreement by the municipality, that its activity is improving the weary neighborhood.

As part of the activity, The Network collaborate with businesses in the Chen center, producing public events or initiating a communal discount in local shops. MB says: “Cooperation with the businesses is a nice thing. It is elementary for us to work with the pubs and the grocery store because their target audience is similar to ours. We want to address young people, and that is their audience, too”. When asked about the needs of the other neighborhood’s residents, she admits: “I cannot say that our activities represent the neighboring residents”. This intensive activity of placemaking in the public space of Neighborhood B does not necessarily address the residents who are not members of The Network. MB is aware of this but says: “At least they [residents who are not part of the community] should feel that it does not hurt them. It seems to me, by and large, that it does not harm them”.

GA, another activist of The Network in Neighborhood B, says, “The events show that The Network did a good job making Chen center its home”. It seems that the goal of The Network’s activists has been achieved, and community members are comfortable in the public spaces of Neighborhood B and Chen center, although many live in other parts of the city (

Figure 5). This is not necessarily the case with other local inhabitants.

3.4.2. Professional Placemaker’s Role

The placemaker in this type of project appears to be collaborative, engaging in cooperative activity and highly attentive, although dedicated mainly to the voices of the specific group. When asked about the participants in the events and services that The Network promotes, MB, The Network activist, admits: “Most of our public are members of The Network. There are a lot of families, but between you and me, they’re not active participants, but because the Chen center is their backyard”. The rare participation of neighbors in activities reflects their remoteness and that they do not necessarily feel comfortable with The Network. The activists do not aim to challenge this. While the community creates active places laden with initiatives, the neighborhood residents remain backstage. Their participation is reserved and partial.

4. Concluding Discussion

Placemaking processes affect the function of the space, its quality and the degree to which it is suitable for the residents. They are becoming popular among local authorities, donors, artists and communities in Israel, as in other places. The typology we offered contributes to the existing literature on placemaking and applies to planners and placemakers. It illustrates that the placemaking idea takes on various forms and modes. Despite the similar end products, both aesthetically and in terms of financial investment, even the ways the projects were formulated and implemented are diverse. This is caused by the lack of a clear definition, an agreed methodology, or an absolute goal for placemaking.

The present study focuses on uses of placemaking in Israel’s southern region. Our findings suggest defining the relationships between the various actors, including funders, professional planners, municipal authorities and community delegates, through forms of placemaking: traditional, governmental, artistic-economic and segregative. Thus, observing different types of motivation for the placemaking process (

Figure 1,

X-axis,

Table 1) teaches us that intrinsic motivations may stem from the community’s desire to have meaningful public spaces and to become stronger, as described in the literature [

13,

16]. However, it may also lead to segregated public spaces, in which people from a specific community feel welcome while others may feel unwanted. When projects are driven and motivated by external parties, such as donors, artists, local authorities, and other interested in the space, the relationships between parties are also affected.

We also observed the target types of placemaking projects (

Figure 1,

Y-axis,

Table 1), demonstrating a range of targets. Broad goals are inclusive by nature, strengthening community resilience and empowering residents, while specific, predetermined and targeted goals may advance the involved artists and empower the governmental or political bodies while adapting public spaces to their needs. Broad goals usually contain and enable various needs and allow for change and adjustment while in motion, but narrow, focused goals push the project in the direction of a particular facility or single element in space.

Accordingly, we have seen that traditional placemaking contains many characteristics essential to the original form described in the literature. Traditional placemaking goes hand-in-hand with the ideas of New Urbanism, which aim to improve urban space by building urban communities, human diversity, and multiplicity of interactions [

17]. The findings show that community members accompany such placemaking projects from inception to finished product. According to the literature, this type of placemaking involves people or groups living around a shared public space [

7,

20,

25,

26,

37]. Lin and Dong [

29] stress that such involvement is critical for groups that want to provide the place with meaning and identity. External bodies, such as donors and community planners, participating in the process are also aware of the importance of high participation and involvement of community members in planning and implementation. Accordingly, we found that the end products in projects of this type had a medium level of finish because they were created by local participants from the community, not necessarily professional experts. In traditional placemaking, a key characteristic is the emphasis on the process, rather than the result, while creating a sense of place and creating a space with a local and community identity.

However, community placemaking also includes projects driven by outsiders, again affecting the relationships between residents, donors and placemakers. The study exposed organizational motivation leading to governmental placemaking. These projects stem from the willingness of an organization or local authority to address social issues, land values, or neglect of public space through placemaking. In the example presented above, the student association of Ben-Gurion University endeavors to operate near the campus and drive specific social and spatial processes. Other entrepreneurs, such as authorities and even philanthropic associations, sometimes make placemaking a “product”. Placemaking is offered as a synthetic tool for improving public space. The weak point is that governmental placemaking does not “belong” to the community, but the entrepreneurs run the project, changing the essence and sterilizing the central idea. The study finds more broadly that when an external factor is detached from the community, many interests hide under the guise of placemaking and the creation of local communities. This also fits with the claim that hidden political interests influence the nature of placemaking projects in collaboration between different sectors [

14].

The very arrival of outsiders, whose familiarity with the specific space is limited and whose specialization is in the design or construction of public space projects, highlights that placemaking has become a product and a channel for transferring funds. This is how artistic-economic placemaking develops; it is driven by donors, artists, or entrepreneurs who want to create a beautiful place representing their creativity. In the example we presented, the developers and artists want to emphasize that they are active placemakers and add another beautiful project to the list. In both of these motivations, the relationship with the community is partial. Despite the many efforts, the result may be a “white elephant” that does not communicate with or contribute to the environment. In other cases too, but especially in the context of economic-artistic placemaking, the result is usually a beautiful and aesthetic result. Yet, the community context is relatively weak and its contribution to the values of community strengthening is secondary.

An entirely different motivation drives the last type, segregative placemaking, which begins with a high motivation to build a community and design a proper public space to serve it. Still, once the place is dedicated to a specific community, it might exclude residents who are not part of it. In such projects, the public space is designed to realize the identity and needs of a particular community. This type of placemaking demonstrates how a group with power can appropriate the public space by imparting a distinct identity. The Network was presented as an example of a relatively homogeneous group seeking to build a community life for itself. The group has a great deal of dominance in creating space, but its point of view is internal, and the interest in involving residents who are not part of the community is low. It is precisely the placemaking methodology that associates the place with the community. Even when public participation evenings take place, those present are active community members. Thus, a process of spatial segregation is created.

Community placemaking was thus born as an alternative to planning processes carried out by professionals and government bodies who are not the ones using the space. In addition, placemaking is an effective alternative to complex and lengthy planning procedures. Jane Jacobs [

24] (p. 238) claimed: “Cities have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody”. Placemaking has proven its potential to do that and also empower residents and deepen their sense of belonging.

Besides appreciating placemaking ideas, the present study offers a critical perspective on the loose definition of the concept, and highlights some the lurking drawbacks. We point out the overuse of the placemaking concept and technique in ways that are not necessarily optimal and may even harm an existing community fabric. The study illustrates the complex relationship between the various factors and their direct impact on the process. Because of these relationships, the general title that defines a project as community placemaking can be used to embellish a less communal or non-communal process due to the complex relationship. Further research might deepen the connection between different types of placemaking, the spatial product, and its effect on the social fabric. Follow-up research is important because placemaking has entered formal planning and there is need to examine how this tool helps meet existing needs.

Professional planners could use this research to examine the goal and initiation of the placemaking projects they engage in. Establishing relationships between residents and other actors on the above principles can create a contributive social atmosphere. Particularly, planners are invited to apply the suggested outline for enhancing their projects and escaping the governmental, artistic-economic and segregative placemaking traps.