Abstract

Learners of heritage languages (HLs) comprise a heterogeneous population. Because of their diverse backgrounds, the ways in which their HL identity develops in a study abroad (SA) context may vary. This paper presents a case study of Chinese heritage language learners (CHLLs) from a university in Australia who participated in a short-term SA program in China. To achieve a holistic understanding of the learners’ identity development, this study adopted a three-dimensional framework of HL identity development, applied a narrative approach and focused on individual differences. Data were collected from 34 post-program journal reflections from CHLLs. The learners’ narratives indicated that they assigned different degrees of importance and distinct meanings to the SA experience with respect to their HL identity development. While some actively explored their HL identities, others took a more outsider stance and did not develop much in terms of HL identity. We identified several possible statuses of CHLLs’ identification, which were conceptualised as focused explorer, balanced explorer, partial explorer, meanderer and outsider. Future intervention could provide personalised feedback, comments and guidance on students’ post-program reflective journals, either in a more specific or holistic manner, and acknowledge each HL learner’s advantages and limitations in their reflections.

1. Introduction

Learners of heritage languages (HLs) comprise a heterogeneous population, including those who may speak a Chinese heritage language (CHL). He [1] (p.1) defined a Chinese heritage language learner (CHLL) as an individual ‘who was raised in a home where Chinese was spoken, who spoke or at least understand the language and was to some degree bilingual in Chinese and in English’. With particular reference to Australia, Mu [2] (p. 27) defined CHLLs as ‘those who have Chinese ancestry; who are educated primarily in English, and therefore may or may not speak or understand a Chinese language; and may be bilingual in a Chinese language and English’. Thus, CHLLs comprise a diverse group of people in terms of language use patterns and country of origin.

Because of their diverse backgrounds, the ways in which heritage speakers view themselves in relation to their languages and heritage communities vary greatly, with some readily adopting a dual linguistic and cultural identity and others feeling more reluctant to do so [3]. However, the heterogeneity in CHLLs’ identities and the associated social, cultural and historical ramifications have received little attention from scholars [4]. Many of the studies on CHLLs have been conducted in the sociocultural context of North America, and a demand thus exists for studies in other diasporic contexts, such as Australia [2]. Although the identity of Australian CHLLs has been investigated in the home-country context [2,5,6,7,8,9,10], little evidence has been found in the study abroad (SA) context where the dominant language is Chinese.

Previous SA studies have highlighted the heterogeneity of SA sojourners’ developmental trajectories. For example, Gu, Schweisfurth and Day [11] problematised the essentialist view of international students as a homogeneous group, especially regarding their linguistic backgrounds and possession of linguistic capital. Moreover, Jessup-Anger and Aragones [12] examined students’ self-identification in a short-term SA program and classified the participants into four types: loner, mediator, messenger and learner. Each type of student benefited from a unique set of strategies to maximise the SA experience. Similarly, Dimmock and Leong’s [13] study identified three types of SA students’ decision-making styles for career planning. Since heritage learners also comprise a heterogeneous group, it is necessary to investigate their diverse developmental trajectories when studying in the country of their ethnic heritage.

Attention to the heterogeneity of CHLLs in SA-in-China programs is relevant to culturally sustaining pedagogy (CSP) [14], which can be a significant contributor to the sustainable development of the Chinese heritage language and of multicultural regions, such as Australia. Paris [14] argues that traditional approaches to multicultural education (e.g., deficit approaches and resource/asset pedagogies) often prioritise assimilation to dominant cultural norms. Moreover, the widely accepted term ‘culturally relevant pedagogy’ [15] does not explicitly support the goal of sustaining cultural diversity. Therefore, Paris and Alim advocate for a shift towards CSP that seeks to ‘perpetuate and foster—to sustain—linguistic, literate, and cultural pluralism as part of schooling for positive social transformation’ [16] (p. 1). The authors [17] further argue that to sustain heritage and community practices, it is essential to comprehend how young people express their racial and ethnic identities, language use, literacy and cultural traditions in both conventional and evolving ways and to avoid the assumption of unidirectional correspondences between race, ethnicity, language and cultural ways of being. Research on CHLLs’ experiences of diverse patterns of identity development through participation in an SA program in China will inform educators of the ways of enhancing language and culture curricula towards the goals of CSP.

In this paper, we present a case study of CHLLs from a university in Sydney, Australia, who participated in a short-term SA program in Beijing, China. To achieve a holistic understanding of the learners’ identity development, we adopted a three-dimensional framework of heritage language (HL) identity development, applied a narrative approach and focused on individual differences. Specifically, we sought to answer the following research questions:

- What were the different patterns of HL identity development of the CHLLs in the short-term SA program?

- How can such patterns inform program practitioners and HL learners?

2. Literature Review

2.1. CHLLs’ Identity

Identity has always been at the core of HL education. In the field of CHL education, language inheritance is frequently considered a demographic factor, which predicts language learning. For example, Oh and Fuligni [18] reported a significantly positive relationship between ethnic identity subscales and the HL proficiency of Chinese descendants. Comanaru and Noels [19] found that the sense of relatedness to Chinese family and community was the most consistent predictor of a self-determined orientation to CHL learning. Xiao and Wong’s [20] study indicated that heritage identity could partly explain writing anxiety.

Other research has focused on the multifaceted and dynamic nature of CHLLs’ identity and how it is constructed through interactions and language use. Many such studies are concerned with how individuals are formed as subjects, how they adopt their subject position and how they experience social variations across time and space. Wong and Xiao [21] found that CHLLs’ identities were flexibly formed and possessed and produced and practised variably through CHL learning. Likewise, Chao [22] reported that, while CHLLs’ priority was to seek an identity in the English-speaking community when younger, during their adulthood, their ethnic identity became the impetus towards learning their native tongue. In these studies, Chinese identity was constantly renegotiated.

In Australia, Mu [2,5,6,7] used Bourdieu’s sociological framework, which consists of three core concepts—habitus (dispositions), capital (social resources) and field (current state of play of a particular social arena)—to interpret the identity of CHLLs. Identity is understood as a habitus that underpins durable cognitive structures. Mu’s studies found that students’ engagement with their CHL was closely correlated with their habitus of Chineseness and their various cultural, social and symbolic capitals.

The aforementioned studies were carried out in home-country contexts; however, we aimed to broaden the research on CHL learners’ identities by exploring the SA context. The following will turn to the literature on HL learners’ identities in the SA context.

2.2. HL Learners’ Identity in the SA Context

Previous research has shown that not all HL learners can be successfully integrated into the local society when going to the place of their ethnic origin, which may lead to identity negotiation. For instance, while the descendants of immigrants reported in Petrucci’s [23] study had a successful experience of integration, Riegelhaupt and Carrasco [24] suggested that a return to the ancestral country did not guarantee a warm welcome in host family settings.

In the Chinese context, Jing-Schmidt et al. [25] compared the narratives of four CHLLs participating in an SA program. While two participants affirmed the motives and goals for their study and derived positive identities from their accomplishments, the other two encountered racial bias as the locals treated them differently from their Euro-American peers. Liu [26] investigated foreign-born Chinese students’ experiences of studying in Chinese higher institutions and found that they usually suffer cultural conflicts and passive emotional barriers in China because they may be treated as outsiders by the local people. The international students of Chinese origin in Hu and Dai’s [27] study reflected various senses of identity in different stages of intercultural learning in China: when they started the learning journey, they were considered ‘international students’, but in the process of experiencing the new context, they realised that they were seen as ‘domestic’ rather than international because of their ‘Chinese’ appearance, which positioned them between different groups. To survive in the new context, these students strategically developed an identity as intercultural in-betweeners. These studies highlight the complex and ambivalent status of CHLLs’ experiences while studying abroad in China.

Our study differs from these previous studies by focusing on CHLLs’ identity developments, which are more pertinent to the linguistic dimension of the experience based on Benson et al.’s [28] second language (L2) identity framework.

2.3. The Framework of HL Identity Development

This study draws on Benson et al.’s [28] three-dimensional L2 identity development to examine identities, which are evoked and developed in the SA context. This framework focuses on the facets of identity that are projected by the use of an L2, which distinguishes it from other identity models that pay less attention to linguistically related domains. Another advantage is that the framework identifies areas of identity development related to language learning in the SA environment and is therefore drawn from the empirical findings of a wide range of SA research. The framework has been applied in several empirical studies [29,30] and is acknowledged in Kinginger’s [31] review-based article on SA.

Benson et al. [28] proposed a continuum of possible outcomes from studying abroad, ranging from L2 proficiency to personal competence, with a large part of the continuum occupied by a complex area, which is best described as L2 identity. In their model, L2 identity concerned ‘any aspect of a person’s identity that is connected to their knowledge or use of a second language’ [28] (p. 174), which corresponds to Block’s [32] concept of linguistic identity as involving several dimensions, such as expertise in language use, affiliation with users of the language and language inheritance. L2 identity development in the SA context denotes

the ways in which different facets of identity are integrated and aligned, in accordance with the need to use L2 to project identities that are in harmony with other relevant facets of the participants’ personal and social identities in the (SA) environment.[28] (p. 179)

Benson et al. [28] identified three potential areas of development in L2 identity in SA programs:

- Identity-related L2 development: Language competence, which leads to the successful expression of desired insider identities. In this dimension, learners are able to describe what they have been able to do with the L2 (e.g., problem solving and making friends), which links their L2 proficiency to their self-identification as a successful sojourner;

- Linguistic self-concept development: Self-evaluation on learning/using the L2—that is, how learners perceive their ability as language learners and their progress. A sense of becoming a user rather than a learner of the language was a key finding of Benson et al.’s research;

- L2-mediated personal development: Achievements with respect to character changes or self-exploration with the L2 as the medium. Examples of pertinent personal growth include maturity, tolerance, open mindedness, independence and cultural awareness.

In this study, we adapted this model to place explicit emphasis on HL identity development. Informed by the model, our working definition of HL identity development was ‘any aspect of a person’s identity that is connected to their knowledge or use of their HL’. It differs from L2 identity development in that the learner’s heritage background is relevant in the process of identity formation, enactment and negotiation. The potential areas for HL identity development through SA programs include the following three dimensions:

- Language development related to heritage identity: Language competence, which leads to the expression of a desired heritage identity. For example, expanding on previously limited knowledge about Chinese gained from family and taking the advantage of the HL to solve problems when studying abroad.

- HL self-concept development: Self-evaluation on learning/using the HL, that is, how learners perceive their abilities as HL learners/users and their progress.

- HL-mediated personal development: Achievements involving character changes or self-exploration with the HL as the medium, such as being inspired by the values expressed by Chinese idioms or developing an understanding of the heritage culture through the use of the HL in communication.

This study was built on our research team’s previous research [33] identifying the major themes regarding the three dimensions of HL identity development among a group of Australian-Chinese students in a short-term SA program. In that study, we enriched the extension of each dimension of Benson et al.’s [28] framework by identifying themes more pertinent to HL learning. In the dimension of language development related to heritage identity, we found that CHLLs could adapt to the local life better than their non-heritage counterparts, which gave them more opportunities to use the language in life settings. They also perceived SA as an ideal setting to explore language variations and accents. In the dimension of HL self-concept development, we found CHLLs’ self-positioning in relation to the local people provided a reference point for reflecting on what they had achieved as heritage speakers, and they developed their desire to master the HL accordingly. For the dimension of HL-mediated personal development, we found that aspects of CHLLs’ personal growth, such as independence and worldviews, were sometimes mediated by the HL through interaction.

While our previous study identified common themes among all HL learners, in this study, we focused on the distinct types of their development trajectories based on the different extents to which each of the three dimensions of HL identity were developed.

2.4. Gaps in the Literature

In summary, this study addresses the following gaps in the literature. First, there has been little research on CHLLs’ identity development in the SA context wherein students learn the heritage language in their places of ancestral origin. Second, Benson et al.’s three-dimensional identity development framework has not been employed to explore the different dimensions of HL identity development. Third, the heterogeneity of CHLLs’ identity development during SA has not been sufficiently understood or conceptualised. In addressing these gaps, this study will offer suggestions for recognising and sustaining the diversity of heritage cultures as well as Australia’s cultural pluralism.

3. Methodology

We applied a narrative approach to investigate identity. The identities in our study can be understood as sociocultural narratives [32], which were produced through a process of representation [34]. Benson et al.’s [28] study on L2 identity in the SA context also indicated that narrative is well suited to describing individuals’ personal development. Therefore, the narrative approach was considered appropriate for our study.

3.1. Participants and Data Collection

This study drew on the narratives collected from the post-program journal reflections of 34 CHLLs from an Australian university who had participated in an intensive cohort-based SA program hosted by a university in Beijing, China, over a period of three weeks. The Chinese classes at the host university were offered at three levels (fundamental, beginning-intermediate and advanced) and taught by local teachers. Before the SA program, the participants had not taken any formal language lessons at the host university, although some of them had attended Chinese language schools or learned Chinese informally. During the SA program, the host institution organised out-of-class cultural excursions to tourist attractions (e.g., The Great Wall, The Forbidden City, 798 Art District, etc.) in addition to language classes. Since the program recruited both heritage and non-heritage learners, the CHLLs in this study had lessons with their Australian peers as a cohort. In our observation of the program and informal communication with local teachers, heritage and non-heritage identities were not explicitly addressed or catered to in language classes, although the teachers were aware that heritage learners may have complex linguistic backgrounds.

The learners were invited to tell stories of their SA experiences and comment on the ways they had developed or changed. We did not emphasise identity as a topic and allowed themes to emerge from the data. Guided questions elicited narratives with respect to the following: (1) memorable language and cultural learning experiences, (2) evaluations of the experience in relation to previous knowledge/assumptions, (3) aspects that were difficult or confusing in the program and (4) anything significant gained from the program. Follow-up questions were sent to some students for clarification or elaboration. Each of the 34 written narratives collected ranged from 500 to 1000 words. The research received ethics approval from the Australian institution (Project number: 2019/395) and Institution Approval Letter from the Chinese institution. Participation in the study was voluntary, and the participants signed a consent form. The code names given to the learners are used in this article to protect their privacy (e.g., S1 refers to Student 1).

Because this study is part of a larger project, which includes both heritage and non-heritage learners, this study was limited in that the guided reflective journal questions were not directly related to heritage identity. While such an approach resulted in some information regarding the learners’ heritage background being omitted (e.g., family structure and parental policies), it nevertheless allowed salient heritage-identity-related narratives to emerge naturally, thus well illustrating how the participants identified themselves as CHLLs in the SA program and the extent to which HL identity development was a pronounced aspect of their SA experience.

3.2. Narrative Analysis Procedures

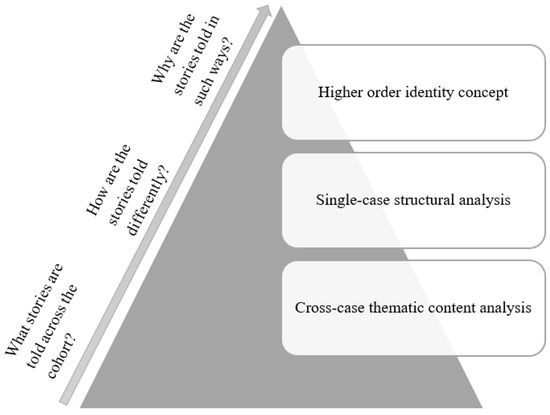

This study followed the analytical steps suggested by Menard-Warwick [35] while integrating a range of useful techniques [36] for narrative research. The procedures are illustrated by the pyramid model in Figure 1. NVivo 12 was used to facilitate the data coding and analysis process. The following research activities were carried out in each step:

Figure 1.

Narrative analysis procedures.

Step 1: Thematic analysis. Menard-Warwick [35] noted that thematic approaches in narrative analysis focus on the content of the narratives—that is, what stories are told. The content of identity development narratives often reflects an individual’s recollection of and reflection on key experiences related to their sense of self [37]. Thematic analysis was adopted in the study of Benson et al. [28] at the initial stage of their analysis of L2 identity development, which involved a process of systematic reading, thematic coding and reinterpreting texts within predefined categories. In our study, we first identified developments connected to Chinese heritage background and then categorised them into the three dimensions of HL identity development. We also identified narratives that indexed an outsider identity, which could be used as evidence of distancing from the heritage identity. This step of the thematic analysis served as the foundation for the later step of finding patterns across the dataset.

Step 2: Structural analysis. This step focused more on how the stories were told, as it looked at ‘how narratives are organised… to achieve a narrator’s strategic aims’ [35] (p. 77). In this study, we focused on how the narratives in the students’ journals were organised within the three dimensions of HL development, for instance, whether a journal focused on any specific domain of development or had a more balanced account of all three domains. This approach aimed to reveal how the different CHLLs assigned varied meanings to their SA experiences in terms of HL identity development. Specifically, we created a Framework Matrix in NVivo 12 with the cases of the learners in rows and the thematic codes in columns. We then used the ‘auto summarise’ function to generate summaries of each cell, based on which we manually composed more concise summaries to replace the original journal content. We also calculated the number of nodes (i.e., the number of journal segments coded) and the coverage (i.e., the percentage of words of a journal coded) in each cell to provide a general distribution of themes. Notably, this qualitative study only used numbers and percentages as indicative and facilitative tools. We always referred to the original texts and interpreted the codes in their context when deciding on the most appropriate narrative type of a reflective journal. The numeric results are shown in Table A1 in Appendix A. This step allowed us to observe cross-case differences and single-case characteristics.

Step 3: The previous steps led us to develop a higher level identity concept [38] for each narrative based on its unique pattern. This step ran in parallel to Steven and Doerr’s [39] approach of identifying different types of narratives. For example, where developments were irrelevant to any of the three dimensions of HL identity and showed evidence of a foreigner, traveller or Westerner identity, the narratives were categorised as the ‘outsider’ type according to their self-positioning; the narratives of those who had some form of development related to their HL identities were conceptualised as the ‘explorer’ type (which denotes that they actively explored their HL identities during the SA program) with several sub-categories to represent variations. The full list of the higher level identity concepts of the learners is provided in Table A1, Appendix A.

4. Data Analysis and Findings

The students’ narratives indicated that they assigned different degrees of importance and distinct meanings to the SA experience with respect to their HL identity development. In other words, how and the extent to which CHLLs regarded the SA-in-China context as a space for exploring their HL identities varied across the cohort. While some actively explored their HL identities, others took a more outsider stance and did not develop much in terms of HL identity. The narratives of the former group were further categorised into four subgroups, namely ‘focused explorer’, ‘balanced explorer’, ‘partial explorer’ and ‘meanderer’, each with a distinct narrative pattern.

4.1. Focused Explorer

The focused explorer students focused on one dimension of their HL identities in their narratives, which means the SA sojourn had particular significance to that domain of development. Such feature was manifest in the distribution of the coding when more codes were assigned to one dimension of HL identity development than the other two dimensions.

Some students focused on the dimension of language development related to heritage identity. Both S20 and S32 wrote extensively about how they improved their HL after conquering the initial challenges of the program. They were apprehensive about their language abilities and struggled during the initial stage:

S32: I thought I was fluent in Chinese when I first enrolled in this unit, since I spoke Chinese from a very young age. I could write, read and speak Chinese… What a surprise! I was no way near fluent compared to a local… I felt overwhelmingly unprepared for this unit [program] by the time I got in bed [on the first day of arrival].

S20: …before the end of the first weekly exam, my weaknesses had become sorely obvious and left me greatly disheartened. Although my interest in Chinese had kept me decently proficient in recognising and reading, I was completely unable to write the characters from nothing. I became anxious about every assessment, and confronting my fear of failure in these tasks was what challenged me the most in terms of my language studies.

Both students actively explored ways to conquer the difficulties they faced and ultimately improved their language abilities.

S20: I endured this by keeping the thought of self-improvement always at the forefront of my mind, and I am so proud to have completed the language course and for conquering my fears… My parents and siblings joined me in Beijing during my last week of studies…, and I was most humbled and grateful to find that I had become so comfortable and confident in expressing myself that I was able to facilitate and guide them through their Beijing travels.

S32: I realised in 2 days [that] speaking Chinese to the locals not only increased my Chinese abilities, but we were less likely to get scammed… I never thought learning Chinese was a burden, but I never realised how useful it was until I needed it.

These examples demonstrate that for some CHLLs, the SA experience was prominent in that it attested to their language abilities, and they acquired more all-round development as a result of it. Many of the CHLLs had access to Chinese through family talk, but they were able to gain a better idea of their language abilities in other communication contexts. These students also had a greater sense of what they could manage to do using the HL.

Other students focused on the dimension of HL self-concept development. Based on their journal entries, the SA experience allowed them to gain a clearer idea of what makes a better HL learner and speaker.

S6: …My own identity as an Australian-born Chinese (ABC) has been shaped largely by my family and close relatives. However, I now realise that this has limited my understanding of what the Chinese language represents and its relationship with Chinese culture. [Studying abroad provided] me [with] the opportunity to test my own understanding… The formal classroom setting also revealed to me the limitations of my previously informally learnt Chinese.

S25: Another misconception that I held was that I would gain little from this program due to my Chinese heritage. Between my friend and I, I was the only person with any knowledge of Chinese. Thus, I was forced to completely rely on my own limited speaking abilities… It was this sink-or-swim situation that enabled me to rapidly develop my confidence and skills.

The data suggest that CHLLs appreciated the opportunities for formal or organised language learning in the SA program. S25 thought they would gain little from the SA program but then realised that needing to help their peers during the program as part of the organised learning was beneficial. S6 also found the ‘formal classroom setting’ desirable. They all refreshed their self-concepts as more professional, experienced learners of the HL.

Some students focused on exploring the third dimension, HL-mediated personal development, in their journals. These students emphasised how studying abroad was an enlightening experience compared to their previous connections with China, as they were able to reflect on their values, perspectives and growth through intentional learning.

S15: The local civilians enlightened my discoveries towards a common belief our teacher mentioned in class: ‘the value of the doctrine of the Mean’ (中庸之道). Personally, I believe that this idea of unity is something that has been lacking [in] Western culture…

S30: As an individual with a Chinese background, language and culture has always been of importance within my life, whether it is speaking the language to elderly family members or the cultural importance of special occasions such as Chinese New Year. However, beyond these experiences that I have grown up with, the Chinese language and historical culture has been largely unexplored. The interactions and immersion with the local community and learning about the new environment has challenged my independence through the need to communicate in Chinese.

In the examples, the learners’ personal growth was mediated by their HL. S15 was inspired by a traditional Chinese value conveyed by an idiom, while S30 developed independence as a result of having to use their HL in unfamiliar settings away from the family setting.

It is thus clear that the focused learners placed strong emphasis on how their HL identities developed through the program, meaning that the SA experience had salient value for a specific domain of their HL identity development.

4.2. Balanced Explorer

Some of the students’ narratives could be given the higher order identity of ‘balanced explorer’, since the codes for their HL identity development were distributed among all three dimensions. These students’ exploration of the three domains of HL identity potentially integrated to form a coherent whole, as shown in S5′s narrative:

(a) Having attended Chinese school for Cantonese growing up, I vividly remember the difficulties of learning a language and [the] dedication required to master it… Throughout my initial studies [in the program], I faced difficulties with distinguishing tones and pronunciation, especially with tongue placements… Despite this, I remained resilient, eager to overcome these challenges, as mastery would provide a strong foundation for future success in Mandarin. To do so, I took a two-pronged approach, listening to the audio from the textbook to practise both my pronunciation and listening skills before reinforcing this through practising with Advanced class friends and engaging with locals. This method proved to be successful, as I… progressively saw my speaking and listening skills improve. (b) I developed greater confidence in my Mandarin and… reaffirmed that I was capable [of learning] the language if I consistently practised and immersed myself within the city… (c) I was ready to put aside the comforts I had in Australia for something new and refreshing in Beijing. Subsequently, my [SA] experience was a journey of discovery, one that would allow me to gain both a better grasp of Mandarin and deeper insights into my culture and heritage.

In this narrative, part (a) was coded as language development related to heritage identity, since the student’s improvement in learning Mandarin was built on their past experience of learning Cantonese. Part (b) was coded as HL self-concept development because it was indicative of the student’s increased confidence in learning their HL. Part (c) was coded as HL-mediated personal development because the student’s self-discovery was mediated by conquering the challenges met when learning about the HL and culture (i.e., putting aside the comforts they had previously enjoyed). S5′s narrative thus indicates that the three domains of HL identity development are mutually beneficial.

4.3. Partial Explorer

Partial explorers were those who developed only slightly in one or two domains of their HL identities. Their narratives only covered one or two dimensions of the HL identity model, and each dimension contained only one code. This means that these students did not explore aspects of their HL identities in great depth like the focused explorers, nor did they reflect holistically on all three dimensions like the balanced explorers. For instance, S22 reflected on how they developed linguistically based on their prior experiences as a heritage learner:

S22: Although Chinese is not a foreign language for me, I struggle to read or write Chinese characters. Growing up, my parents stressed the importance of speaking Mandarin at home, but I never took Chinese classes, which limited my exposure to Chinese characters. Coming to Beijing allowed me to learn a vast range of new characters both in the classroom and while travelling.

However, compared to S20 and S32 (focused explorers), S22 was less articulate about what they could manage to achieve through the HL and how their struggles were resolved. Moreover, compared to S5 and S19 (balanced explorers), S22 did not connect their HL development to their self-concept and personal development as an HL learner or speaker. This pattern was also observed among the other partial explorers. For another example, S12 developed in both the domains of language development related to heritage identity (i.e., their Chinese abilities improved because the teaching content in the SA was different from their previous experience in Australian Chinese schools) and HL-mediated personal development (i.e., through interacting with the local Chinese students, they realised that the students were friendlier than originally imagined). Notwithstanding, their account of each domain of development remained short and shallow, and HL self-concept development was not described in their journal.

4.4. Meanderer

The meanderer category refers to someone who developed in some domains of their HL identity, but they also took an outsider stance at some points in their narrative, suggesting that they switched between different subject positionings when narrating their SA story. Although other CHLLs may have also taken an in-between stance, only the meanderers used identity markers for outsiders in their narratives. These CHLLs tried to explore their heritage identities to some extent, but the obstacles to integration were pronounced, or they may have maintained some bias or essentialist views on cultural differences. A typical example is S28, who developed in HL self-concept as a more knowledgeable person of their ethnic heritage:

S28: We also took home countless historical lessons that were especially fascinating. Although this wasn’t my initial plan, as an Australian with a Chinese background, I can finally return to my parents and tell them to stop pestering me about my lack of knowledge of the history of China.

However, improved knowledge of China did not guarantee an increased affinity to the place of ethnic origin:

S28: While conversing with my language partner (a doctorate student at [the host institution]), I came to a very important realisation about my life growing up in Sydney. Listening to descriptions of the harsh reality for Chinese students, the ever increasing competition and the unsympathetic pressures induced by their parents, I realised just how lucky I am to have experienced childhood in Australia. This was an unexpected discovery that I never thought I’d be making. Never have I thought that after staying at [the host institution], I’d develop a newfound appreciation for my parents who decided to raise me in Australia.

S28′s newfound appreciation for being raised in Australia is arguably a kind of ‘HL-mediated personal development’; however, the outsider identity prevented them from exploring the cultural differences they encountered in greater depth. For instance, the student could have queried why Chinese students had such competition and how the underlying reasons are related to China’s current developmental stage and speed. This may have helped the student resonate more with the cultural and historical logic behind the phenomena. However, the student did not attempt to probe these issues and simply interpreted the phenomena as them being lucky to have been raised in Australia. Other meanderers’ narratives showed a similar pattern, that is, they regarded their home country cultural identity as a dominated subjectivity when encountering cultural conflicts and differences in the SA context (see also [27]). CHLLs tended to take an outsider stance, like that of foreigners, Westerners or Australians, when they narrated these encounters.

4.5. Outsider

In the outsiders’ narratives, we found no evidence that these CHLLs’ development through the SA program related to their heritage background. Their HL identity development was rarely actively explored, and their outsider identities were more prominent. For example:

S3: I learnt how navigating unknown streets in a foreign city can easily get overwhelming, and although most people are courteous, a few will try to take advantage of your foreigner status to rip you off… The difficulty of learning and speaking a second language has made me appreciate and respect international students and immigrants more and has honed key intercultural skills.

S11: The [program] has had a momentous impact on myself, stemming from my initial expectations that I would merely learn basic and useless phrases in Chinese and see tourist attractions with my pre-existing friendship group. While my expectations were met, an unanticipated appreciation for exchange programs was developed, compounded with the growth of new friendships and cherished memories. I believe this [can be] attributed to the diverse group of… other students who commenced a similar journey with me.

S13: My trip to China gave me valuable insights into a different culture… I refrained from being ethnocentric and did not evaluate Chinese culture from my perspective but instead ‘lived in their shoes’.

S3′s narrative showed a strong foreigner identity, which was strengthened by their experiences of being overwhelmed and taken advantage of as a foreign student in China. Being a CHLL did not constitute a significant aspect of the sojourn experience. Similarly, S11′s narrative featured a tourist–student identity. Their perception of personal development was related to establishing new friendships with Australian peers. Although S13 mentioned that they ‘tried to see life from the perspective of the Chinese people’, the use of the term ‘ethnocentric’ indicated that the learner did not identify as Chinese in terms of ethnicity. They may have improved their intercultural understanding, but it had little to do with their heritage identity. All these examples suggest that the outsider students did not actively explore their HL identities through the SA program, and their HL identity development was minimal.

5. Discussion

We drew on CHLLs’ post-program reflective journal narratives to uncover different trajectories of HL identity development through a short-term SA program. Our contribution to the literature is thus our recognition of distinguishable patterns in CHLLs’ identity development during their SA experiences. The findings provide a more holistic and comprehensive picture of CHLLs by highlighting their diversity and heterogeneity, which aligns with the pursuit of CSP that explicitly advocates sustaining and extending the richness of our pluralist society.

Our data analysis demonstrated that some heritage learners were more active in exploring their HL identity development than others, and the development trajectories differed not only in degree of significance but also in pattern. SA program practitioners and instructors should be informed about and prepared for HL learners’ diverse expectations, levels of readiness and investment in SA programs as a venue for HL identity development. Our findings may serve to inspire stakeholders given the theoretical and practical issues.

Theoretically, the three-dimensional HL identity development framework, which was adapted from Benson et al.’s [28] L2 identity development framework, is a useful tool to understand how HL learners’ projection of identity is related to their knowledge or use of their HL. In the SA context, the framework can help determine how different facets of a learner’s HL identity are ‘integrated and aligned’ and ‘in harmony with other relevant facets of the participants’ personal and social identities in the [SA] environment’ [28] (p. 179). Analysing the distribution of development among the three dimensions of the framework enabled us to determine the extent to which different dimensions of the HL identity are integrated and aligned. Interpreting HL identity development in relation to the occurrence of outsider identity markers helped us explore the relationship between HL identity and other facets of personal and social identities, such as foreigner and tourist–student identities, in the SA context.

As proponents of CSP suggest, young people both rehearse traditional versions of ethnic and linguistic difference and offer new visions of it [40,41]. Therefore, CSP emphasises the plural and evolving nature of youth identity and cultural practices [17]. This study demonstrates how young college students’ heritage language identity is intertwined with other facets of their youth identity. Taking into account the contemporary and evolving features of youth identity is important for sustaining heritage and community practices, since it sensitises us to the fact that youth continue to live in a world in which ‘cultural and linguistic recombinations flow with purpose’ [17] (p.90), and they need pedagogies that respond to this new reality. Meanwhile, CSP is also committed to reflecting critically on how youth culture can perpetuate systemic inequities [17]. As the data in this study showed, less active explorers, such as meanderers and outsiders, may lack mindfulness in heritage cultural preservation and may perpetuate a sense of dominant culture superiority. This is not conducive to sustaining cultural pluralism and social equity in multicultural Australia, and it is a primary concern of CSP. Therefore, more effort is needed to raise these students’ awareness of the impacts of their cultural practices as CHLLs on the sustainable development of the heritage language and of a multicultural society. As mentioned in the Methodology section, identity issues were not explicitly catered to either in classes or in out-of-class activities. We advocate for collaboration between program practitioners at both host and home universities in experimenting with embedding CSP in their program designs.

Practically, this study suggests that different types of HL learners can maximise their SA experience by applying different approaches. The heterogeneity of CHLLs, immigrants and their conception of ‘Chineseness’ has been discussed in previous studies [42]. Caution is therefore needed when making over-generalised or over-simplified assumptions about CHLLs’ motivations and goals for SA programs. While Jing–Schmidt et al. [25] recommended that programmatic intervention should align the SA program design with CHLLs’ learning goals, we also stress that HL learning goals and priorities may vary. We could learn more about these diverse possibilities through sophisticated qualitative analyses of individual differences. The typology of narratives identified in this study does not suggest that the students’ HL identities were fixed; instead, their HL identities were constantly shaped and reshaped. However, we could glimpse the subject position taken by the students at the point where they reflected on their progress made through the SA program.

We identified several possible statuses of CHLLs’ identification, which were conceptualised as focused explorer, balanced explorer, partial explorer, meanderer and outsider. Future intervention could provide personalised feedback, comments and guidance on students’ post-program reflective journals, either in a more specific or holistic manner, and acknowledge each HL learner’s advantages and limitations in their reflections. Below are suggestions for different types of learners:

- For focused and balanced explorers, we could acknowledge the advantages in their depth and breadth of exploration while suggesting possibilities for further reflection.

- For partial explorers and meanderers, more emphasis may be placed on guidance for understanding their difficulties and cultural differences; this is because both types of learners are willing to explore but encounter obstacles to more in-depth engagement or thorough understanding. Both this and previous studies have demonstrated that one of the major challenges HL learners face is a lowered self-esteem and sense of empowerment if they speak a non-prestigious variety of their HL [43] or if the traditional Chinese culture instilled in them by their family is different from the Chinese culture they experience in person in China [27]. The data from more active explorers showed that conquering these difficulties and interpreting them as the richness and diversity of their cultural heritage helped channel their negative emotions and contribute to positive HL identity growth.

- Outsiders may not be as ready to actively explore their HL identities, and their subject positioning should be respected. Their renewed appreciation of their identities related to their home countries or cultural belonging, in the case of presence, should also be recognised. Previous literature has suggested that a comprehensive recognition of their home culture helps learners alternate between cultural identities [44], which is inducive to the formation of an intercultural identity [45]. The outsiders in this study all developed some form of intercultural or global identity, which is plausible. However, it should also be recognised that the opportunity to explore their heritage identities through the SA experience was not fully utilised. Since stronger heritage identification is associated with better HL proficiency and language maintenance [18,19], evoking these outsiders’ interest in exploring their HL identities is a necessary consideration for SA program interventions.

Our practical recommendations for providing personalised post-reflection feedback are especially useful for short-term cohort-based SA programs, such as the one in this study. The cohort nature of the program means that many of the suggestions made in previous studies on HL schools and other HL-learner-only learning contexts were not applicable. Since heritage and non-heritage learners are intermingled, tailoring instructions and learning activities to meet the specific learning goals of HL learners (e.g., focusing on grammar and literacy skills; see Ref [27]) may not always be achievable. Moreover, the motivations and goals of HL learners can vary. Personalised feedback informed by theory and empirical data on post-program reflective journals is more feasible. Since an SA program can potentially renew or enrich the funds of knowledge [10,46] students have gained from family and develop their HL identities through different trajectories, they may gain various funds of knowledge not available in their home country settings. Proper guidance based on students’ own knowledge and reflections through post-program reflective journal feedback may help HL learners construct more positive re-entry identities—a prominent issue in SA sojourners’ longer term development through short-term programs in the SA literature (e.g., Ref [47]).

6. Conclusions

People may have assumptions about HL learners’ identities and expectations regarding their integration in their place of ancestral origin. However, these presumptions may neglect the heterogeneity of this population and the multidimensional features of heritage identity. In this study, we adopted a three-dimensional HL identity framework to analyse CHLLs’ identity development during an SA program in China. Using a narrative approach and within-person analyses of individual cases, we scrutinised how and to what extent different aspects of their HL identities were evoked, negotiated and developed to become an integral part of each learner’s personal and social identities as a holistic person in the SA environment. The findings highlight how CHLLs experience diverse patterns of identity development through participating in an SA program in China. This will inform us of the ways of enhancing our language and culture curricula towards the goals of culturally sustaining pedagogy.

A limitation of this study was the small number of CHLLs. The findings therefore cannot be generalised to other study settings, such as long-term SA programs. Further, the domains of identity development in this cohort and the main patterns listed in this paper do not provide a full representation of all CHLLs. Moreover, the impact of different class levels on students’ HL development was not fully explored. Table A1 seems to indicate that more advanced learners tended to be more active explorers, whereas there was a bigger chance that fundamental-level learners were meanderers and outsiders. However, the study is inconclusive in this regard due to its limited sample and scope. We recommend that future studies extend the HL identity development model to a larger cohort of CHLLs to validate the generalisability of the findings or add to them.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, P.T. and L.T.; methodology, P.T. and L.T.; formal analysis, P.T. and L.T.; writing—original draft preparation, P.T.; writing—review and editing, L.T.; visualisation, P.T.; supervision, L.T.; project administration, P.T.; funding acquisition, L.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of University of Sydney (Project number: 2019/395).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy concerns.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the two reviewers who generously gave their time to provide insightful and constructive feedback on this article. Their thoughtful comments and suggestions have greatly improved the quality of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Matrix query for thematic codes across cases.

Table A1.

Matrix query for thematic codes across cases.

| No. | Code Name | Journal Word | Level of Class | Theme 1 1 (NoC/ NoW/ CC) 2 | Theme 2 (NoC/ NoW/ CC) | Theme 3 (NoC/ NoW/ CC) | Theme 4 (NoC/ NoW/ CC) | Higher Order Identity Concept |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | S20 | 535 | Advanced | 2 201 37.57%3 | 1 133 24.86% | 0 0 0.00% | 0 0 0.00% | focused explorer (theme 1 focused) |

| 2 | S32 | 657 | Advanced | 2 191 29.07% | 1 36 5.48% | 0 0 0.00% | 0 0 0.00% | focused explorer (theme 1 focused) |

| 3 | S01 | 527 | Beginning-Intermediate | 0 0 0.00% | 2 73 13.85% | 0 0 0.00% | 0 0 0.00% | focused explorer (theme 2 focused) |

| 4 | S06 | 949 | Fundamental | 1 205 21.60% | 3 394 41.52% | 0 0 0.00% | 0 0 0.00% | focused explorer (theme 2 focused) |

| 5 | S25 | 553 | Beginning-Intermediate | 1 20 3.62% | 2 65 11.75% | 0 0 0.00% | 0 0 0.00% | focused explorer (theme 2 focused) |

| 6 | S29 | 1022 | Beginning-Intermediate | 0 0 0.00% | 2 152 14.87% | 1 79 7.73% | 0 0 0.00% | focused explorer (theme 2 focused) |

| 7 | S15 | 539 | Advanced | 0 0 0.00% | 1 46 8.53% | 2 119 22.08% | 0 0 0.00% | focused explorer (theme 3 focused) |

| 8 | S18 | 503 | Beginning-Intermediate | 1 36 7.16% | 0 0 0.00% | 2 189 37.57% | 0 0 0.00% | focused explorer (theme 3 focused) |

| 9 | S30 | 501 | Beginning-Intermediate | 0 0 0.00% | 0 0 0.00% | 2 183 36.53% | 0 0 0.00% | focused explorer (theme 3 focused) |

| 10 | S05 | 548 | Fundamental | 1 193 35.22% | 1 21 3.83% | 1 85 15.51% | 0 0 0.00% | balanced explorer |

| 11 | S19 | 900 | Advanced | 1 24 2.67% | 1 83 9.22% | 1 55 6.11% | 0 0 0.00% | balanced explorer |

| 12 | S33 | 890 | Advanced | 1 122 13.71% | 1 94 10.56% | 1 30 3.37% | 0 0 0.00% | balanced explorer |

| 13 | S08 | 550 | Advanced | 0 0 0.00% | 1 99 18.00% | 1 69 12.55% | 0 0 0.00% | partial explorer |

| 14 | S12 | 519 | Advanced | 1 72 13.87% | 0 0 0.00% | 1 69 13.29% | 0 0 0.00% | partial explorer |

| 15 | S14 | 867 | Advanced | 1 25 2.88% | 1 94 10.84% | 0 0 0.00% | 0 0 0.00% | partial explorer |

| 16 | S04 | 959 | Beginning-Intermediate | 1 123 12.83% | 0 0 0.00% | 0 0 0.00% | 0 0 0.00% | partial explorer |

| 17 | S02 | 566 | Beginning-Intermediate | 0 0 0.00% | 1 97 17.14% | 1 58 10.25% | 0 0 0.00% | partial explorer |

| 18 | S22 | 971 | Beginning-Intermediate | 1 62 6.39% | 0 0 0.00% | 0 0 0.00% | 0 0 0.00% | partial explorer |

| 19 | S31 | 895 | Beginning-Intermediate | 0 0 0.00% | 1 39 4.36% | 0 0 0.00% | 0 0 0.00% | partial explorer |

| 20 | S21 | 923 | Beginning-Intermediate | 1 105 11.38% | 0 0 0.00% | 0 0 0.00% | 2 64 6.93% | meanderer |

| 21 | S16 | 519 | Advanced | 0 0 0.00% | 0 0 0.00% | 1 32 6.17% | 1 146 28.13% | meanderer |

| 22 | S17 | 1143 | Beginning-Intermediate | 1 25 2.19% | 3 180 15.75% | 0 0 0.00% | 1 79 6.91% | meanderer |

| 23 | S28 | 550 | Beginning-Intermediate | 0 0 0.00% | 1 38 6.91% | 0 0 0.00% | 1 95 17.27% | meanderer |

| 24 | S26 | 929 | Advanced | 1 98 10.55% | 1 32 3.44% | 0 0 0.00% | 1 180 19.38% | meanderer |

| 25 | S03 | 504 | Fundamental | 0 0 0.00% | 0 0 0.00% | 0 0 0.00% | 2 61 12.10% | outsider |

| 26 | S07 | 538 | Beginning-Intermediate | 0 0 0.00% | 0 0 0.00% | 0 0 0.00% | 1 19 3.53% | outsider |

| 27 | S09 | 934 | Fundamental | 0 0 0.00% | 0 0 0.00% | 0 0 0.00% | 1 66 7.07% | outsider |

| 28 | S10 | 549 | Beginning-Intermediate | 0 0 0.00% | 0 0 0.00% | 0 0 0.00% | 1 98 17.85% | outsider |

| 29 | S11 | 550 | Fundamental | 0 0 0.00% | 0 0 0.00% | 0 0 0.00% | 1 145 26.36% | outsider |

| 30 | S13 | 937 | Fundamental | 0 0 0.00% | 0 0 0.00% | 0 0 0.00% | 1 76 8.11% | outsider |

| 31 | S23 | 537 | Beginning-Intermediate | 0 0 0.00% | 0 0 0.00% | 0 0 0.00% | 3 79 14.71% | outsider |

| 32 | S24 | 823 | Advanced | 0 0 0.00% | 0 0 0.00% | 0 0 0.00% | 1 45 5.47% | outsider |

| 33 | S27 | 550 | Fundamental | 0 0 0.00% | 0 0 0.00% | 0 0 0.00% | 2 65 11.82% | outsider |

| 34 | S34 | 554 | Beginning-Intermediate | 0 0 0.00% | 0 0 0.00% | 0 0 0.00% | 2 141 25.45% | outsider |

1. Theme 1 = Language development related to heritage identity; Theme 2 = HL self-concept development; Theme 3 = Personal development mediated by HL; Theme 4 = Outsider identity. 2. NoC = Number of codes; NoW = Number of words of all codes; CC = Coding coverage; the numbers in the columns are the values for these items. 3. The colouring of cells was generated in Nvivo based on NoC. The larger the NoC, the darker the cell colour. This provides a general visual representation of the pattern; however, we also considered NoW and CC and went back to the original text when interpreting the data and determining the type of higher order identity concept expressed in a journal reflection.

References

- He, A. Toward an identity theory of the development of Chinese as a heritage language. Herit. Lang. J. 2006, 4, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, G.M. Learning Chinese as a Heritage Language: An Australian Perspective; Multilingual Matters: Blue Ridge Summit, PA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dressler, R. “There is no Space for Being German”: Portraits of Willing and reluctant Heritage Language Learners of German. Herit. Lang. J. 2010, 7, 162–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, A.W. An Identity-Based Model for the Development of Chinese as a Heritage Language. In Chinese as a Heritage Language: Fostering Rooted World Citizenry; He, A., Xiao, Y., Eds.; National Foreign Language Resource Center, University of Hawai’i at Manoa: Manoa, HI, USA, 2008; pp. 109–122. [Google Scholar]

- Mu, G.M. Heritage Language learning for Chinese Australians: The role of habitus. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 2014, 35, 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, G.M. Learning Chinese as a heritage language in Australia and beyond: The role of capital. Lang. Educ. 2014, 28, 477–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, G.M. Looking Chinese and Learning Chinese as a Heritage Language: The Role of Habitus. J. Lang. Identity Educ. 2016, 15, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y. L2 Self of Beginning-Level Heritage and Nonheritage Postsecondary Learners of Chinese. Foreign Lang. Ann. 2014, 47, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.L.; Moloney, R. Identifying Chinese heritage learners’ motivations, learning needs and learning goals: A case study of a cohort of heritage learners in an Australian university. Lang. Learn. High. Educ. 2014, 4, 365–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.L.; Moloney, R. Moving Between Diverse Cultural Contexts: How Important is Intercultural Learning to Chinese Heritage Language Learners? In Interculturality in Chinese Language Education; Jin, T., Dervin, F., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2017; pp. 151–176. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Q.; Schweisfurth, M.; Day, C. Learning and Growing in a “foreign” Context: Intercultural Experiences of International Students. Compare 2010, 40, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessup-Anger, J.E.; Aragones, A. Students’ Peer Interactions Within a Cohort and in Host Countries During a Short-Term Study Abroad. J. Stud. Aff. Res. Pract. 2013, 50, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimmock, C.; Leong, J.O.S. Studying overseas: Mainland Chinese students in Singapore. Compare 2010, 40, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, D. Culturally Sustaining Pedagogy: A Needed Change in Stance, Terminology, and Practice. Educ. Res. 2012, 41, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladson-Billings, G. Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. Am. Educ. Res. J. 1995, 32, 465−491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alim, H.S.; Paris, D. What is culturally sustaining pedagogy and why does it matter? In Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies: Teaching and Learning for Justice in a Changing World; Paris, D., Alim, H.S., Eds.; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Paris, D.; Alim, H.S. What are we seeking to sustain through culturally sustaining pedagogy? A loving critique forward. Harv. Educ. Rev. 2014, 81, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.S.; Fuligni, A.J. The Role of Heritage Language Development in the Ethnic Identity and Family Relationships of Ado-lescents from Immigrant Backgrounds. Soc. Dev. 2010, 19, 202–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comanaru, R.; Noels, K.A. Self-Determination, Motivation, and the Learning of Chinese as a Heritage Language. Can. Mod. Lang. Rev. 2009, 66, 131–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Wong, K.F. Exploring Heritage Language Anxiety: A Study of Chinese Heritage Language Learners. Mod. Lang. J. 2014, 98, 589–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.F.; Xiao, Y. Diversity and Difference: Identity Issues of Chinese Heritage Language Learners from Dialect Back-grounds. Herit. Lang. J. 2010, 7, 153–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, D.-L. Chinese for Chinese Americans: A Case Study. J. Chin. Lang. Teach. Assoc. 1997, 32, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Petrucci, P. Heritage scholars in the ancestral homeland: An overlooked identity in study abroad research. Socioling. Stud. 2007, 1, 275–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riegelhaupt, F.; Carrasco, R.L. Mexico host family reactions to a bilingual Chicana teacher in Mexico: A case study of language and culture clash. Biling. Res. J. 2000, 24, 405–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing–Schmidt, Z.; Chen, J.Y.; Zhang, Z. Identity Development in the Ancestral Homeland: A Chinese Heritage Perspective. Mod. Lang. J. 2016, 100, 797–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S. Searching for a sense of place: Identity negotiation of Chinese immigrants. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2015, 46, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Dai, K. Foreign-born Chinese students learning in China: (Re)shaping intercultural identity in higher education institution. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2021, 80, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, P.; Barkhuizen, G.; Bodycott, P.; Brown, J. Study abroad and the development of second language identities. Appl. Linguist. Rev. 2012, 3, 173–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkhuizen, G. Investigating multilingual identity in study abroad contexts: A short story analysis approach. System 2017, 71, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.; Tracy-Ventura, N.; McManus, K. Anglophone Students Abroad: Identity, Social Relationships and Language Learning; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kinginger, C. Identity and Language Learning in Study Abroad. Foreign Lang. Ann. 2013, 46, 339–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, D. Second Language Identities; Continuum: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, P.; Liang, C.; Liu, Y. Australian-Chinese heritage language identity development in a short-term study abroad pro-gramme. Chin. Appl. Linguist. Res. (Chin. J.) 2019, 9, 134–158. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, E.E.; Langellier, K.M. The performance turn in narrative studies. Narrat. Inq. 2006, 16, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menard-Warwick, J. A Methodological Reflection on the Process of Narrative Analysis: Alienation and Identity in the Life Histories of English Language Teachers. TESOL Q. 2011, 45, 564–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riessman, C.K. Narrative Methods for the Human Sciences; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kuper, L.E.; Mustanski, B.S. Using Narrative Analysis to Identify Patterns of Internet Influence on the Identity Development of Same-Sex Attracted Youth. J. Adolesc. Res. 2014, 29, 499–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, E.; Bell, N.J.; Corson, K.; Kostina-Ritchey, E.; Frederick, H. Girls Discuss Choice of an All-Girl Middle School: Narrative Analysis of an Early Adolescent Identity Project. J. Early Adolesc. 2012, 32, 465–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, P.; Doerr, B. Trauma of discorvery: Women’s narratives of being informed they are HIV-infected. AIDS Care 1997, 9, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paris, D. Language across Difference: Ethnicity, Communication, and Youth Identities in Changing Urban Schools; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Alim, H.S.; Reyes, A. Complicating race: Articulating race across multiple social dimensions. Discourse Soc. 2011, 22, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J. Discourses of ‘Chineseness’ and superdiversity. In The Routledge Handbook of Language and Superdiversity; Creese, A., Blackledge, A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 181–193. [Google Scholar]

- Roca, A.; Gutiérrez, J. Sociolinguistic Considerations. In Professional Development Series Handbook for Teachers K–16: Spanish for Native Speakers; American Association of Teachers of Spanish and Portuguese, Ed.; Harcourt College: Fort Worth, TX, USA, 2000; pp. 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, A.M.; Barker, G.G. Confused or multicultural: Third culture individuals’ cultural identity. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2012, 36, 553–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X. Construction of intercultural identity: A two-directional extension model. Intercult. Commun. Res. 2009, 1, 154–165. [Google Scholar]

- González, N.; Moll, L.C.; Amanti, C. Funds of Knowledge: Theorizing Practices in Households, Communities, and Classrooms; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, P.; Tsung, L. Learning Chinese in a Multilingual Space: An Ecological Perspective on Studying Abroad; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).