Enhancing Sustainability with the Triple-Layered Business Model Canvas: Insights from the Fruit and Vegetable Industry in Spain

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Research Methods

3.1. Overall Methodological Concept

3.2. Company-Level Analysis

3.3. Company-Data Collection and Analysis

4. Results

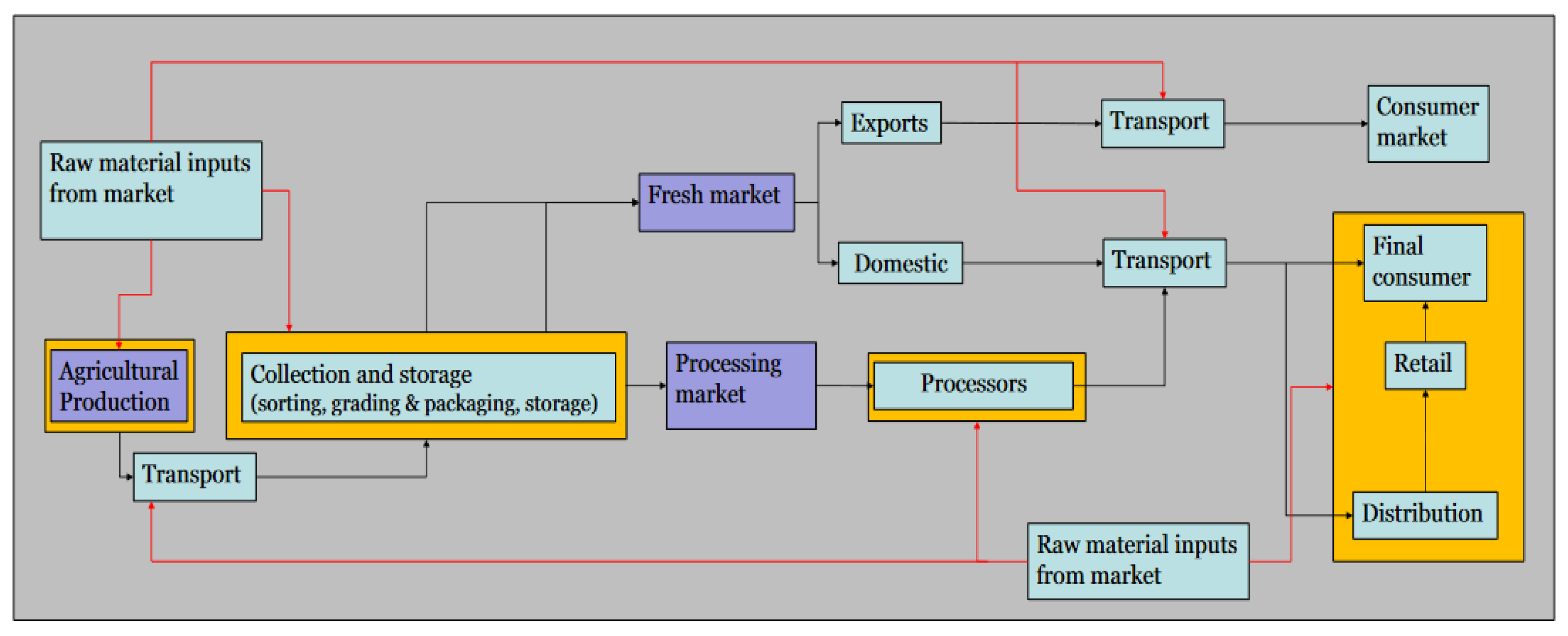

4.1. Sector-Level Analysis

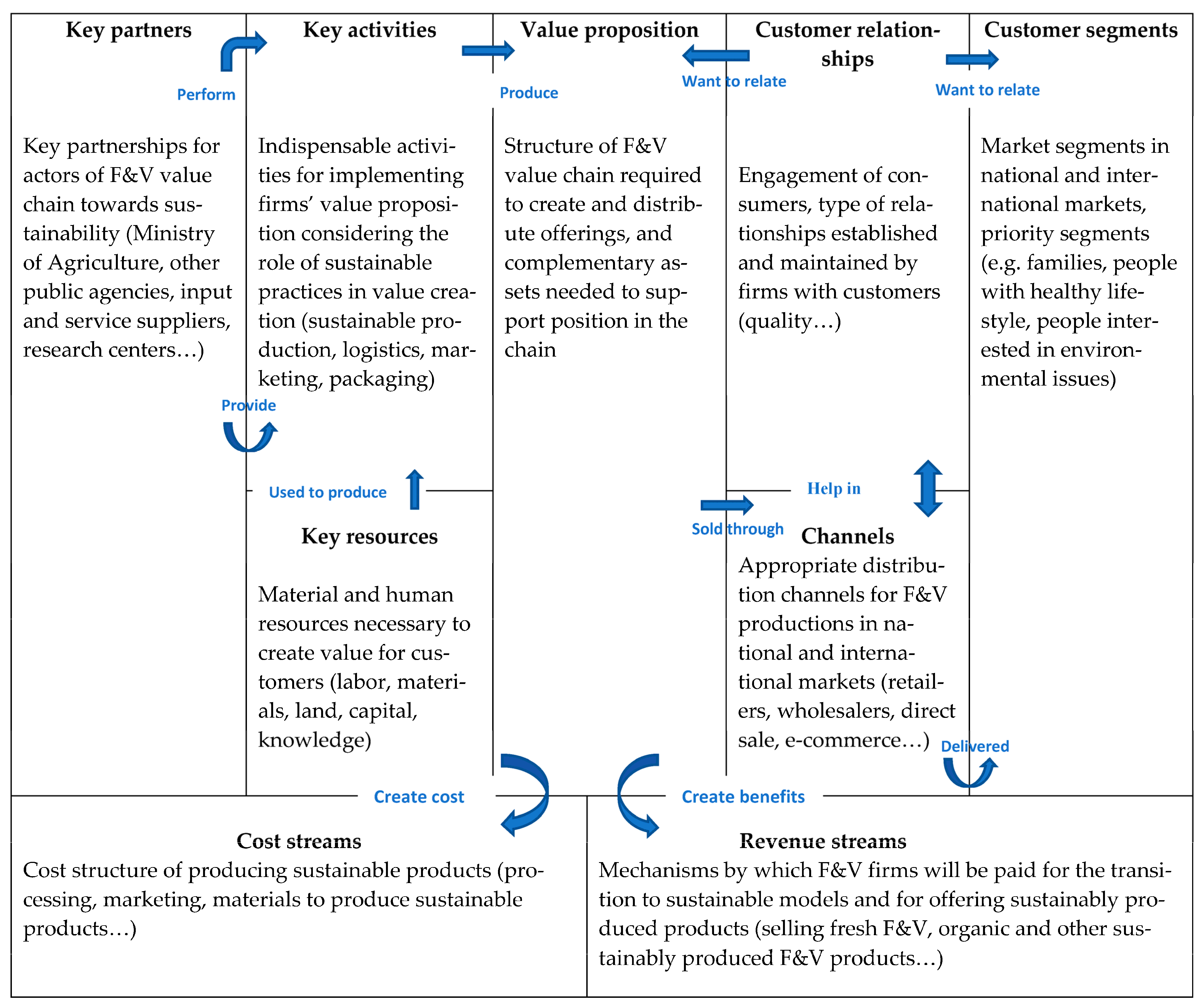

4.2. Company-Level Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hinrichs, C.C. Transitions to sustainability: A change in thinking about food systems change? Agric. Hum. Values 2014, 31, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maye, D.; Duncan, J. Understanding Sustainable Food System Transitions: Practice, Assessment and Governance. Sociol. Ruralis 2017, 57, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaitán-Cremaschi, D.; Klerkx, L.; Duncan, J.; Trienekens, J.H.; Huenchuleo, C.; Dogliotti, S.; Contesse, M.E.; Rossing, W.A.H. Characterizing diversity of food systems in view of sustainability transitions. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 39, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD. Declaration on Transformative Solutions for Sustainable Agriculture and Food Systems. 2022. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/agriculture/ministerial/documents/OECD%20Agriculture%20Ministerial%20DECLARATION%20EN.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2022).

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A.; et al. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaltegger, S.; Lüdeke-Freund, F.; Hansen, E.G. Business Models for Sustainability: A Co-Evolutionary Analysis of Sustainable Entrepreneurship, Innovation, and Transformation. Organ. Environ. 2016, 29, 264–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, H.; Ulvenblad, P.-O.; Ulvenblad, P. Towards a Conceptual Framework of Sustainable Business Model Innovation in the Agri-Food Sector: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bernardi, P.; Azucar, D. Innovative and Sustainable Food Business Models. In Innovation in Food Ecosystems. Entrepreneurship for a Sustainable Future; Springer: London, UK, 2020; pp. 189–221. [Google Scholar]

- El Bilali, H. The Multi-Level Perspective in Research on Sustainability Transitions in Agriculture and Food Systems: A Systematic Review. Agriculture 2019, 9, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. A Greener and Fairer CAP. 2022. Available online: https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2022-02/factsheet-newcap-environment-fairness_en_0.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- European Commission. Farm to Fork Strategy. For a Fair, Healthy and Environmentally-Friendly Food System. 2020. Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2020-05/f2f_action-plan_2020_strategy-info_en.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- European Commission. EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030. Bringing Nature Back into Our Lives. 2020. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:a3c806a6-9ab3-11ea-9d2d-01aa75ed71a1.0001.02/DOC1&format=PDF (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Hancock, A.; Espinoza, J. Brussels agrees details of world-first carbon border tax. Financ. Times Dec. 2022, 18, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Smetana, S.; Tamásy, C.; Mathys, A.; Heinz, V. Sustainability and regions: Sustainability assessment in regional perspective. Reg. Sci. Policy Pract. 2015, 7, 163–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duque-Acevedo, M.; Belmonte-Ureña, L.; Terán-Yépez, E.; Camacho-Ferre, F. Sustainability and circularity in fruit and vegetable production. Perceptions and practices of reduction and valorization of agricultural waste biomass in south-eastern Spain. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 316, 115270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tort, Ö.Ö.; Vayvay, Ö.; Çobanoğlu, E. A Systematic Review of Sustainable Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Supply Chains. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozancos, J.M.; Jiménez, B. Los desafíos del sector español de frutas y hortalizas en un entorno cambiante. Distrib. Consumo 2019, 158, 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food. Información del Sector de Frutas y Hortalizas en España. 2023. Available online: https://www.mapa.gob.es/es/agricultura/temas/producciones-agricolas/frutas-y-hortalizas/informacion_general.aspx (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Langreo, A.; García Azcárate, T. Las frutas y hortalizas en la economía española: Perspectivas, certezas y tendencias. Distrib. Consumo 2020, 163, 5–22. [Google Scholar]

- De Castro, L. Spanish fresh fruits and vegetables sector. In OECD Fruit and Vegetables Scheme. In Proceedings of the 18th Meeting of the Heads of National Inspection Services, Seville, Spain, 9–11 May 2018; pp. 20–30. [Google Scholar]

- Mercasa. Alimentación en España: Producción, Industria, Distribución y Consumo. 2022. Available online: https://www.mercasa.es/wpcontent/uploads/2022/07/AEE_2021_web.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- Hernández-Rubio, J.; Morillas-Guerrero, J.J.; Galdeano-Gómez, E.; Pérez-Mesa, J.C.; Aznar-Sánchez, J.A.; Fernández-Olmos, M.; Malorgio, G. Fruit and Vegetables Supply Chain Organization in Spain: Effects on Quality and Food Safety. 2016. Available online: http://repositorio.ual.es/bitstream/handle/10835/3857/SAFEMEDworking%20paper%20I%20English-R2.pdf?sequence=8&isAllowed=y (accessed on 22 September 2022).

- Parajuli, R.; Thoma, G.; Matlock, M.D. Environmental sustainability of fruit and vegetable production supply chains in the face of climate change: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 650, 2863–2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsamakas, E. Digital Transformation and Sustainable Business Models. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorić, N.; Marić, R.; Đurković-Marić, T.; Vukmirović, G. The Importance of Digitalization for the Sustainability of the Food Supply Chain. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Bocken, N.; Hultink, E. Design thinking to enhance the sustainable business modelling process—A workshop based on a value mapping process. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 1218–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basile, V. The Triple Layered Business Model Canvas in smart agriculture: The case of EVJA startup. Riv. Piccola Impresa/Small Bus. 2021, 2, 79–113. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, S.C.; Davidson, R.A. Applications of the business model in studies of enterprise success, innovation and classification: An analysis of empirical research from 1996 to 2010. Eur. Manag. J. 2013, 31, 668–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, J.G.C.; Okano, M.T.; Guerra, R.S.; Cordeiro, D.d.S.; dos Santos, H.C.L.; Fernandes, M.E. Analysis of Sustainable Business Models: Exploratory Study in Two Brazilian Logistics Companies. Sustainability 2022, 14, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit, R.; Zott, C. Business Model Innovation: Creating Value in Times of Change. 2010. Available online: https://media.iese.edu/research/pdfs/DI-0870-E.pdf (accessed on 3 October 2022).

- Johnson, M.W.; Christensen, C.M.; Kagermann, H. Reinventing Your Business Model. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2008, 86, 57–68. [Google Scholar]

- Ulvenblad, P.-O.; Ulvenblad, P.; Tell, J. An overview of sustainable business models for innovation in Swedish agri-food production. J. Integr. Environ. Sci. 2019, 16, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boons, F.; Lüdeke-Freund, F. Business Models for Sustainable Innovation: State of the Art and Steps Towards a Research Agenda. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 45, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roome, N.; Louche, C. Journeying Toward Business Models for Sustainability: A Conceptual Model Found Inside the Black Box of Organisational Transformation. Organ. Environ. 2016, 29, 11–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upward, A.; Jones, P. An Ontology for Strongly Sustainable Business Models: Defining an Enterprise Framework Compatible with Natural and Social Science. Organ. Environ. 2016, 29, 97–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M.P.; Short, S.W.; Rana, P.; Evans, S. A literature and practice review to develop sustainable business model archetypes. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, A.; Paquin, R.L. The triple layered business model canvas: A tool to design more sustainable business models. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 1474–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y. Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- López-Nicolás, C.; Ruiz-Nicolás, J.; Mateo-Ortuño, E. Towards Sustainable Innovative Business Models. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakeel, J.; Mardani, A.; Chofreh, A.G.; Goni, F.A.; Klemes, J.J. Anatomy of sustainable business model innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 261, 12120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, W.; Chen, W.; Agyapong, M.; Mordi, C. The business model of Do-It-Yourself (DIY) laboratories—A triple-layered perspective. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 159, 120205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, I.; Sobral, P.; Peças, P.; Henriques, E. A sustainable business model to fight food waste. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 177, 262–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reardon, T.; Timmer, C.P. The Economics of the Food System Revolution. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2012, 4, 225–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bager, T. Institutional and Organisational Change in the European Food Sector: A Meso-Level Perspective. In Strategies and Structures in the Agro-Food Industries; Nilsson, J., van Dijk, G., Eds.; Van Gorcum and Comp BV: Assen, The Netherlands, 1997; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Ménard, C.; Martino, G.; de Oliveira, G.M.; Royer, A.; Saes, M.S.M.; Schnaider, P.S.B. Governing food safety through meso-institutions: A cross-country analysis of the dairy sector. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2022, 44, 1722–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Vladimirova, D.; Evans, S. Creating and Capturing Value Through Sustainability. Res. Manag. 2017, 60, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericsson. Sustainability is a Value Creator for Business and Society; The Ericsson Blog. 2020. Available online: https://www.ericsson.com/en/blog/2020/3/sustainability-value-creator-business-society (accessed on 25 September 2022).

- Maletič, M.; Maletič, D.; Dahlgaard, J.J.; Dahlgaard-Park, S.M.; Gomišcek, B. Do corporate sustainability practices enhance organizational economic performance? Int. J. Qual. Serv. Sci. 2015, 7, 184–200. [Google Scholar]

- Ghauri, P. Designing and conducting case studies in international business research. In Handbook of Qualitative Research Methods for International Business; Piekkari, R., Welch, C., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenhan, UK, 2004; pp. 109–124. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, Y.; Rashid, A.; Warraich, M.A.; Sabir, S.S.; Waseem, A. Case study method: A step-by-step guide for business researchers. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2019, 18, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, I.; Holton, J.A.; Bailyn, L.; Fernandez, W.; Levina, N.; Glaser, B. What Grounded Theory Is…A Critically Reflective Conversation Among Scholars. Organ. Res. Methods 2015, 18, 581–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, K.Y. Applications of Case Study Research; Sage: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Abdul Rahim, M.; Wan Daud, W.N. The Case Study Method in Business. Sch. J. Arts Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2015, 3, 105–109. [Google Scholar]

- Seawright, J.; Gerring, J. Case Selection Techniques in Case Study Research: A Menu of Qualitative and Quantitative Options. Political Res. Q. 2008, 61, 294–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, B.W. Digital Business Models: Concepts, Models, and the Alphabet Case Study; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hienerth, C.; Keinz, P.; Lettl, C. Exploring the Nature and Implementation Process of User-Centric Business Models. Long Range Plan. 2011, 44, 344–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumble, R.; Mangematin, V. Business Model Implementation: The Antecedents of Multi-Sidedness. Adv. Strateg. Manag. 2015, 33, 97–131. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, C. Conceptualizing, Analyzing and Communicating the Business Model. Aalb. Univ. Work. Pap. Ser. 2010, 2, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Zujewski, B. The Return on Investment (ROI) of Sustainable Business. 2022. Available online: https://greenbusinessbureau.com/topics/sustainability-benefits-topics/the-return-on-investment-roi-of-sustainable-business/ (accessed on 19 January 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mili, S.; Loukil, T. Enhancing Sustainability with the Triple-Layered Business Model Canvas: Insights from the Fruit and Vegetable Industry in Spain. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6501. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086501

Mili S, Loukil T. Enhancing Sustainability with the Triple-Layered Business Model Canvas: Insights from the Fruit and Vegetable Industry in Spain. Sustainability. 2023; 15(8):6501. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086501

Chicago/Turabian StyleMili, Samir, and Tasnim Loukil. 2023. "Enhancing Sustainability with the Triple-Layered Business Model Canvas: Insights from the Fruit and Vegetable Industry in Spain" Sustainability 15, no. 8: 6501. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086501

APA StyleMili, S., & Loukil, T. (2023). Enhancing Sustainability with the Triple-Layered Business Model Canvas: Insights from the Fruit and Vegetable Industry in Spain. Sustainability, 15(8), 6501. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086501