Career Planning Indicators of Successful TVET Entrepreneurs

Abstract

:1. Introduction

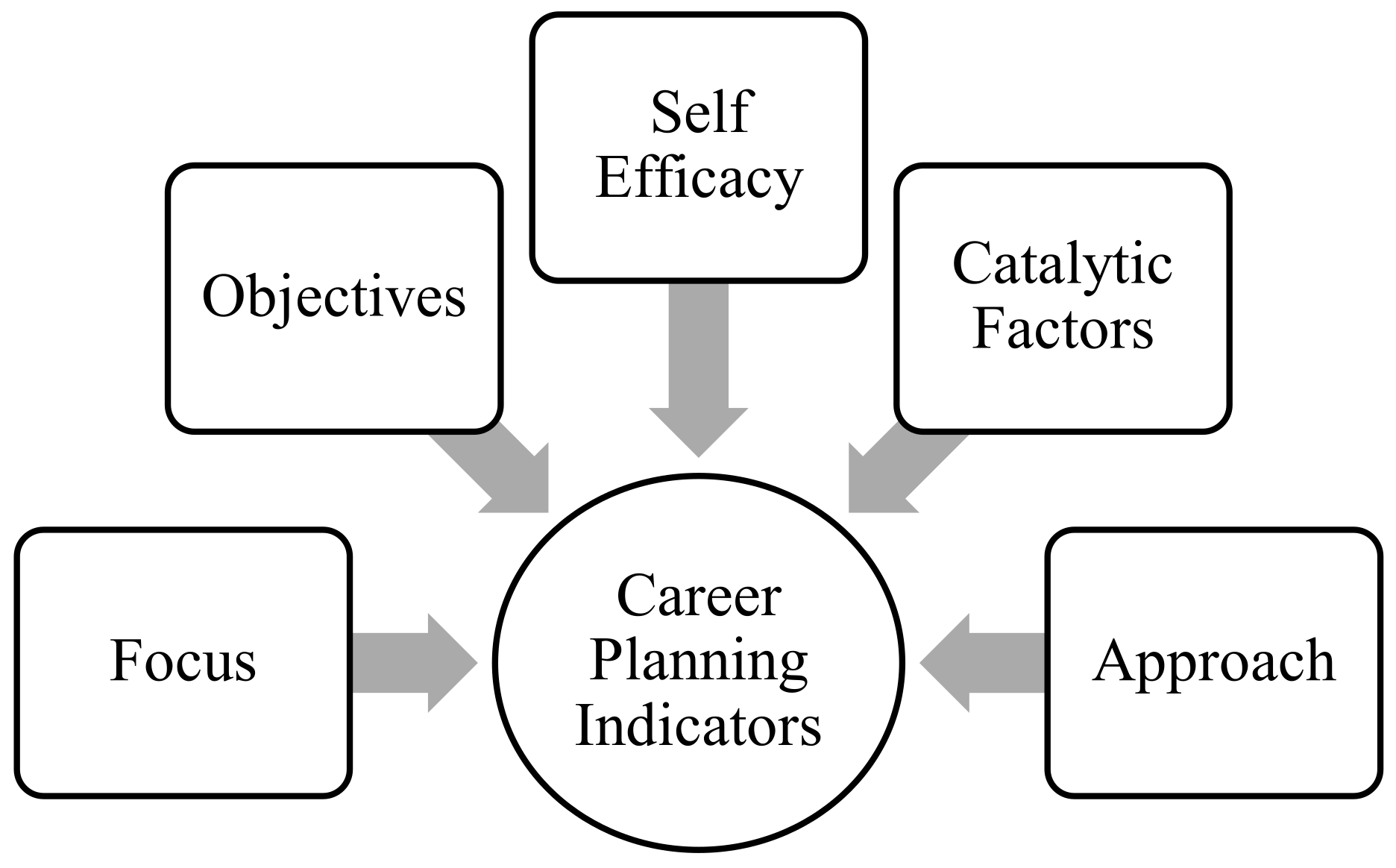

1.1. Conceptual Underpinning and Hypothesis Development of Career Planning

1.2. Focus in Career Planning

1.3. Objectives in Career Planning

1.4. Self-Efficacy in Career Planning

1.5. Catalytic Factors in Career Planning

1.6. Career Planning Approach

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Round 1

2.2. Round 2

2.3. Round 3

3. Results

Career Planning Indicator

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lysova, E.I.; Richardson, J.; Khapova, S.N.; Jansen, P.G. Change-supportive employee behavior: A career identity explanation. Career Dev. Int. 2015, 20, 38–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biemann, T.; Zacher, H.; Feldman, D.C. Career patterns: A twenty-year panel study. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 81, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd, A. Pendidikan Kerjaya dan Pembangunan Modal Insan; Penerbit Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia: Bangi, Malaysia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Malaysia, K.P.T. Entrepreneurship Action Plan 2016–2020; Ministry of Higher Education Malaysia: Putrajaya, Malaysia, 2016.

- Baum, S.; Payea, K. Education Pays the Benefits of Higher Education for Individuals and Society; College Board: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, A.P.; Jorge, F.E.; Pires, C.A.; António, P. The contribution of emotional intelligence and spirituality in understanding creativity and entrepreneurial intention of higher education students. Educ. Train. 2019, 61, 870–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J.L. Making vocational choices: A theory of careers; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank Group. Doing Business 2019. Available online: https://www.doingbusiness.org/content/dam/doingBusiness/media/Annual-Reports/English/DB2019-report_web-version.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- Acs, Z.; Szerb, L.; Lafuente, E.; Lloyd, A. The Global Entrepreneurship Index 2018. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322757639_The_Global_Entrepreneurship_Index_2018/link/5c040b02a6fdcc1b8d503a9e/download (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- Brown, D. Career Information, Career Counseling, and Career Development; Allyn & Bacon: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Räty, H.; Korhonen, M.; Kasanen, K.; Komulainen, K.; Rautiainen, R.; Siivonen, P. Finnish parents’ attitudes toward entrepreneurship education. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2016, 19, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nor, A.R.M. Profil, Indikator, Faktor Kritikal dan Model Perkembangan Kerjaya Berasaskan Komuniti Berpendap Atan Tinggi Dalam Kalangan Lulusan Kolej Komuniti. Ph.D. Thesis, Fakulti Pendidikan UKM, Selangor, Malaysia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gorgievski, M.J.; Stephan, U.; Laguna, M.; Moriano, J.A. Predicting entrepreneurial career intentions: Values and the theory of planned behavior. J. Career Assess. 2018, 26, 457–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behaviour: Reactions and Reflections; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2011; Volume 26, pp. 1113–1127. [Google Scholar]

- Schlaegel, C.; Koenig, M. Determinants of entrepreneurial intent: A meta–analytic test and integration of competing models. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2014, 38, 291–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabiu, A.; Pangil, F.; Othman, S.Z. Does training, job autonomy and career planning predict employees’ adaptive performance? Glob. Bus. Rev. 2020, 21, 713–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adekola, B. Career planning and career management as correlates for career development and job satisfaction. A case study of Nigerian Bank Employees. Aust. J. Bus. Manag. Res. 2011, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puah, P.; Ananthram, S. Exploring the antecedents and outcomes of career development initiatives: Empirical evidence from Singaporean employees. Res. Pract. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2006, 14, 112–142. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, R.; Das, G. The impact of job satisfaction, adaptive selling behaviors and customer orientation on salesperson’s performance: Exploring the moderating role of selling experience. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2013, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, P.H.M. Bimbingan dan Kaunseling Kerjaya; Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Arthur, M.B. The boundaryless career at 20: Where do we stand, and where can we go? Career Dev. Int. 2014, 19, 627–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veloso, E.F.R.; Trevisan, L.N.; da Silva, R.C.; Dutra, J.S. The use of traditional and non-traditional career theories to understand the young’s relationship with new technologies. Rev. Gestão 2018, 25, 340–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lanero, A.; Vázquez, J.-L.; Aza, C.L. Social cognitive determinants of entrepreneurial career choice in university students. Int. Small Bus. J. 2016, 34, 1053–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, J.L.; Fouad, N.A. Career Theory and Practice: Learning through Case Studies; Sage Publications: Singapore, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A.; Walters, R.H. Social Learning Theory; Englewood cliffs Prentice Hall: New York, NY, USA, 1977; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In Action Control; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985; pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Shahab, Y.; Chengang, Y.; Arbizu, A.D.; Haider, M.J. Entrepreneurial self-efficacy and intention: Do entrepreneurial creativity and education matter? Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2018, 25, 259–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, N.; Othman, N.; Buang, N. Konsep kesediaan keusahawanan berdasarkan kajian kes usahawan Industri Kecil dan Sederhana (IKS) di Malaysia. J. Pendidik. Malays. 2009, 34, 187–203. [Google Scholar]

- Şahin, F.; Karadağ, H.; Tuncer, B. Big five personality traits, entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial intention: A configurational approach. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2019, 25, 1188–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, A.T.; Von Korflesch, H. A conceptual model of social entrepreneurial intention based on the social cognitive career theory. Asia Pac. J. Innov. Entrep. 2016, 10, 17–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorgren, S.; Wincent, J. Passion and habitual entrepreneurship. Int. Small Bus. J. 2015, 33, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenholm, P.; Nielsen, M.S. Understanding the emergence of entrepreneurial passion: The influence of perceived emotional support and competences. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2019, 25, 1368–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfeld, C.; Stone III, J.R.; Aragon, S.R.; Hansen, D.M.; Zirkle, C.; Connors, J.; Spindler, M.; Romine, R.S.; Woo, H.-J. Looking inside the Black Box: The Value Added by Career and Technical Student Organizations to Students’ High School Experience. Natl. Res. Cent. Career Tech. Educ. 2006, 31, 121–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbona, C. Promoting the career development and academic achievement of at-risk youth: College access programs. In Career Development and Counseling: Putting Theory and Research to Work; John Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; p. 542. [Google Scholar]

- Linstone, H.A.; Turoff, M. Introduction to the Delphi method: Techniques and applications. In The Delphi Method: Techniques and Applications; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1975; pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Skulmoski, G.J.; Hartman, F.T.; Krahn, J. The Delphi method for graduate research. J. Inf. Technol. Educ. Res. 2007, 6, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiersma, W. Research Methods in Education: An Introduction; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rahim, M.B. Pembinaan Model E-Portfolio Pensijilan Kemahiran Malaysia; Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia: Bangi, Malaysia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Delbecq, A.L.; Van de Ven, A.H.; Gustafson, D.H. Group Techniques for Program Planning: A Guide to Nominal Group and Delphi Processes; Scott Foresman: Northbrook, IL, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Siraj, S.; Abdullah, F. Jangkaan masa depan terhadap aplikasi teknologi dalam kandungan kurikulum dan penilaian sekolah menengah: Satu kajian Delphi. J. Pendidik. 2005, 25, 5–26. [Google Scholar]

- Minghat, A.D.; Yasin, R.M.; Udin, A. The application of the Delphi technique in technical and vocational education in Malaysia. Internafional Proc. Econ. Dev. Res. 2012, 30, 259–264. [Google Scholar]

- Peck, R.; Devore, J.L. Statistics: The Exploration & Analysis of Data; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Nashir, I.M.; Mustapha, R.; Yusoff, A. Membangunkan Instrumen Kepimpinan Dalam Sistem Pendidikan Teknik Dan Vokasional: Penggunaan Teknik Delphi Terubah Suai. J. Qual. Meas. Anal. 2015, 11, 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Roe, A. The Psychology of Occupations; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Super, D.E.; Savickas, M.L.; Super, C.M. The life-span, life-space approach to careers. Career Choice Dev. 1996, 3, 121–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassim, M.A. Membina Kerjaya Akademia; Penerbit UTM Press: Skudai, Malaysia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Galvaan, R. The contextually situated nature of occupational choice: Marginalised young adolescents’ experiences in South Africa. J. Occup. Sci. 2015, 22, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, G.J.; Gallagher, M. Expectations of choice: An exploration of how social context informs gendered occupation. Ir. J. Occup. Ther. 2017, 45, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St-Jean, É.; Mathieu, C. Developing attitudes toward an entrepreneurial career through mentoring: The mediating role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy. J. Career Dev. 2015, 42, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rampton, J. Personality Traits of an Entrepreneur; Forbes/Tech: Jersey City, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, F.R.; Krishnamurthy, J. Future proofing of tourism entrepreneurship in Oman: Challenges and prospects. J. Work. Appl. Manag. 2016, 8, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Guzman, A.B.; Choi, K.O. The relations of employability skills to career adaptability among technical school students. J. Vocat. Behav. 2013, 82, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharf, R.S. Applying Career Development Theory to Counseling; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Haratsis, J.M.; Hood, M.; Creed, P.A. Career goals in young adults: Personal resources, goal appraisals, attitudes, and goal management strategies. J. Career Dev. 2015, 42, 431–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hussain, S.; Malik, M.I. Towards nurturing the entrepreneurial intentions of neglected female business students of Pakistan through proactive personality, self-efficacy and university support factors. Asia Pac. J. Innov. Entrep. 2018, 12, 363–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lent, R.W.; Brown, S.D.; Hackett, G. Career development from a social cognitive perspective. Career Choice Dev. 1996, 3, 373–421. [Google Scholar]

- Stephan, U.; Pathak, S. Beyond cultural values? Cultural leadership ideals and entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 2016, 31, 505–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Azjen, I. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior; Englewood Cliffs: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Arisandi, D. Intensi Berwirausaha Mahasiswa Pascasarjana Institut Pertanian Bogor Pada Bidang Agribisnis (Studi Kasus Pada Mahasiswa Program Magister Sps-Ipb). Marster’s Thesis, Bogor Agricultural University, Bogor, Indonesia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ridha, R.N.; Wahyu, B.P. Entrepreneurship intention in agricultural sector of young generation in Indonesia. Asia Pac. J. Innov. Entrep. 2017, 11, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otache, I. Enhancing the effectiveness of entrepreneurship education: The role of entrepreneurial lecturers. Educ. Train. 2019, 61, 918–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Das, S. An extended model of theory of planned behaviour: Entrepreneurial intention, regional institutional infrastructure and perceived gender discrimination in India. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2019, 11, 369–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, M.D.; Sørensen, J.B.; Dobrev, S.D. A careers perspective on entrepreneurship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2016, 40, 237–247. [Google Scholar]

- Padovez-Cualheta, L.; Borges, C.; Camargo, A.; Tavares, L. An entrepreneurial career impacts on job and family satisfaction. RAUSP Manag. J. 2019, 54, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javadian, G.; Opie, T.R.; Parise, S. The influence of emotional carrying capacity and network ethnic diversity on entrepreneurial self-efficacy: The case of black and white entrepreneurs. New Engl. J. Entrep. 2018, 21, 101–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- García-Rodríguez, F.J.; Gil-Soto, E.; Ruiz-Rosa, I.; Gutiérrez-Taño, D. Entrepreneurial potential in less innovative regions: The impact of social and cultural environment. Eur. J. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2017, 26, 163–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shirokova, G.; Osiyevskyy, O.; Bogatyreva, K. Exploring the intention–behavior link in student entrepreneurship: Moderating effects of individual and environmental characteristics. Eur. Manag. J. 2016, 34, 386–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Profile | Indicator |

|---|---|

| Opportunist | Has a specific but flexible objective in the space and opportunities that existed at that time |

| Aggressive | More emphasis on realistic aspects in career planning, strives to achieve goals but remains specific and flexible |

| Cognitive | Has flexible objectives in career, this is because for them a good career will be obtained if they have excellent academic achievement |

| Conventional | The objective is realistic, considers self-esteem, and is flexible according to the current situation |

| Roe | Has a realistic but specific objective with career choices and does not easily change career objectives |

| Roe-supportive | Has a realistic and specific objective with the objectives of their career, but may sometimes be flexible if circumstances require |

| Systematic | The objectives of their career are specific, realistic, and flexible depending on their career planning in which they will determine the objectives of their career |

| Profile | Indicator |

|---|---|

| Opportunist | Many are influenced by social external elements such as part-time work and exemplary idols |

| Aggressive | The influence of internal and external elements (social) such as part-time and family work |

| Cognitive | Have internal and external (academic) influences such as practical, co-curricular activities, and lecturers |

| Conventional | The influence of more common elements from the interior and exterior |

| Roe | The influence of social interiors is stronger such as a family and work experience |

| Roe-supportive | The influence of social interiors, such as family, is quite strong but academic external influences can also affect career planning such as practical training and external courses |

| Systematic | The catalytic factor depends on the individual themselves based on their career planning |

| Level of Consensus | Modified Scale | Result |

|---|---|---|

| High | 0–1 | Accepted |

| Moderate | 1.01–1.99 | Accepted |

| No Consensus | 2.0 above | Rejected |

| No | Indicator/Item | Round Two | Round Three | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | Med | ROQ | Consensus | M | Med | ROQ | Consensus | ||

| Focus of Career Planning | |||||||||

| 1 | The focus on entrepreneurship should have been since the beginning of study at the institution | 4.4 | 5 | 1.25 | Moderate | 4.2 | 4 | 1.25 | Moderate |

| 2 | Focus on entrepreneurship can also be done after graduation from the institution but requires a stronger effort | 4.2 | 4 | 1 | High | 4.2 | 4 | 1 | High |

| 3 | Focus on entrepreneurial care should be a priority in career planning | 4.5 | 5 | 1 | High | 4.5 | 4.5 | 1 | High |

| 4 | The focus on entrepreneurship makes me more inspired to become an entrepreneur | 4.7 | 5 | 1 | High | 4.3 | 4 | 1 | High |

| 5 | Focus on study should be prioritized in career planning at the institution | 3.8 | 4 | 2.25 | Low | 4 | 4 | 0 | High |

| 6 | Focusing on studies helps improve my academic achievement | 4.4 | 4.5 | 1 | High | 4.4 | 4.5 | 1 | High |

| 7 | Focusing on a special career can be done after graduation | 3.8 | 4 | 2 | Low | 3.4 | 3 | 1.5 | Moderate |

| 8 | Focusing on studies can improve my skills and expertise in the field of study | 4.2 | 4.5 | 1.25 | Moderate | 3.9 | 4 | 1.25 | Moderate |

| No | Indicator/Item | Round Two | Round Three | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | Med | RoQ | Consensus | M | Med | RoQ | Consensus | ||

| Objective in Career Planning | |||||||||

| 9 | Set specific career objectives (career types) in career planning and strive to achieve them | 4.4 | 5 | 1 | High | 4.4 | 5 | 1 | High |

| 10 | Organize long-term career planning (from study time until graduation) | 4 | 4 | 2 | Low | 3.9 | 4 | 2 | Low eliminated |

| 11 | Career planning objectives are logical and in line with one’s abilities (realistic) | 4.5 | 4.5 | 1 | High | 4.5 | 4.5 | 1 | High |

| 12 | Have desire while setting career objectives such as wanting to earn a high salary | 4.4 | 4.5 | 1 | High | 4.4 | 5 | 1 | High |

| 13 | A person’s career planning objectives can be modified (flexible) according to the current situation | 4.2 | 4 | 1 | High | 4.2 | 4 | 1 | High |

| No | Indicator/Item | Round Two | Round Three | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | Med | ROQ | Consensus | M | Med | ROQ | Consensus | ||

| Self-efficacy in Career Planning | |||||||||

| 14 | Optimize career plans that are suitable to the personality of the entrepreneur | 4.6 | 5 | 1 | High | 4.6 | 5 | 1 | High |

| 15 | Confidence that the planned career is in line with the aptitude of the entrepreneur | 4.4 | 4.5 | 1 | High | 4.4 | 4.5 | 1 | High |

| 16 | Confidence that career is planned according to the value (beliefs and self-esteem) held by entrepreneurs | 4.3 | 4 | 1 | High | 4.2 | 4 | 1 | High |

| 17 | Entrepreneurs really know their strengths and weaknesses in planning their career | 4.5 | 4.5 | 1 | High | 4.6 | 5 | 1 | High |

| 18 | Confident that career planning will be able to be implemented by entrepreneurs | 4.7 | 5 | 1 | High | 4.7 | 5 | 1 | High |

| No | Indicator/Item | Round Two | Round Three | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | Med | ROQ | Consensus | M | Med | ROQ | Consensus | ||

| Catalytic Factors in Career Planning | |||||||||

| 19 | Part-time work during study gives exposure to entrepreneurs in the real world of work that can affect their career planning | 4.5 | 4.5 | 1 | High | 4.6 | 5 | 1 | High |

| 20 | Practical training gives entrepreneurs the space to feel the real world of work and have influence in the planning of their career | 4.8 | 5 | 0.25 | High | 4.8 | 5 | 0.25 | High |

| 21 | Formal career guidance by institution helps entrepreneurs make career plans | 4.4 | 4.5 | 1 | High | 4.5 | 5 | 1 | High |

| 22 | Informal career guidance, such as study tours, by institutions helps students to begin career planning | 3.8 | 4 | 2 | Low | 3.8 | 4 | 2 | Low eliminated |

| 23 | Engagement in co-curricular activities improves personality and helps entrepreneurs plan careers better | 3.7 | 4 | 2.25 | Low | 4.1 | 4 | 1.25 | Moderate |

| 24 | Participation in outside courses during study at institutions, such as entrepreneurship courses, gives entrepreneurs a thorough understanding of good career planning | 4.5 | 1 | 1 | High | 4.6 | 5 | 1 | High |

| No | Indicator/Item | Round Two | Round Three | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | Med | ROQ | Consensus | M | Med | ROQ | Consensus | ||

| Career Planning Approach | |||||||||

| 25 | More comfortable planning a career alone without sharing with anyone because of more privacy | 2.8 | 2.5 | 2 | Low | 2.8 | 2.5 | 2 | Low eliminated |

| 26 | Entrepreneurs plan their career based on the internet, as it is convenient and saves time | 2.5 | 2.5 | 1 | High | 2.5 | 2.5 | 1 | High |

| 27 | Entrepreneurs plan careers with close friends and family to share ideas and experiences | 4.5 | 5 | 1 | High | 4.6 | 5 | 1 | High |

| 28 | Entrepreneurs plan careers with people who specialize in careers such as counselors, lecturers, and mentors to get guidance and advice | 4.3 | 4 | 1 | High | 4.4 | 4.5 | 1 | High |

| 29 | Entrepreneurs plan careers with influential people like community leaders, politicians, and so on to gain moral support | 3.6 | 4 | 1.5 | Moderate | 3.8 | 4 | 1.25 | Moderate |

| 30 | Government agencies such as MARA, TEKUN, and others help a lot in career planning after graduation | 3.2 | 3.5 | 2.5 | Low | 3.9 | 3.5 | 2 | Low eliminated |

| Career Planning Indicator | Item |

|---|---|

| i. Focus in Career Planning | Focus on entrepreneurship should have been included since the beginning of study at the institution |

| Focus on entrepreneurship can also be done after graduation from an institution but requires a stronger effort | |

| Focusing on an entrepreneurship career should be a priority in the career planning of entrepreneurs | |

| Focus on entrepreneurship makes entrepreneurs more inspired to become entrepreneurs | |

| Focus on study should be prioritized in career planning at institution | |

| Focusing on studies helps improve the academic achievement of entrepreneurs | |

| Focusing on a special career can be done after graduation | |

| Focusing on studies can enhance the skills and expertise of entrepreneurs in the field of study | |

| ii. Objective in Career Planning | Assigning a specific career objective (career type) must be set in career planning and one must strive to achieve it |

| The objectives of career planning are logical and in line with the ability of the entrepreneurs (realistic) | |

| Assigning a career objective like a high paying salary | |

| The objectives of career planning can be modified (flexible) according to the current situation of entrepreneurs | |

| iii. Self-efficacy in Career Planning | Optimize career plans that are suitable to the personality of the entrepreneur |

| Confidence that the planned career is in line with the aptitude of the entrepreneur | |

| Confidence that career is planned according to the value (beliefs and self-esteem) held by entrepreneurs | |

| Entrepreneurs really know their strengths and weaknesses in planning their career | |

| Confident that career planning will be able to be implemented by entrepreneurs | |

| iv. Catalytic Factors in Career Planning | Part-time work during study gives exposure to entrepreneurs in the real world of work that can affect their career planning |

| Practical training gives entrepreneurs the space to feel the real world of work and have influence in the planning of their careers | |

| Formal career guidance from an institution helps entrepreneurs make career plans | |

| Engagement in co-curricular activities improves personality and helps entrepreneurs plan their careers better | |

| Participation in outside courses during study at institution, such as entrepreneurship courses, gives entrepreneurs a thorough understanding of good career planning | |

| v. Career Planning Approach | Entrepreneurs plan their careers based on the internet, as it is convenient and saves time |

| Entrepreneurs plan careers with close friends and family to sharing ideas and experiences | |

| Entrepreneurs plan careers with people who specialize in careers such as counselors, lecturers, and mentors to get guidance and advice | |

| Entrepreneurs plan career with influential people like community leaders, politicians, and so on to gain moral support |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Muridan, N.D.; Rasul, M.S.; Yasin, R.M.; Nor, A.R.M.; Rauf, R.A.A.; Jalaludin, N.A. Career Planning Indicators of Successful TVET Entrepreneurs. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6629. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086629

Muridan ND, Rasul MS, Yasin RM, Nor ARM, Rauf RAA, Jalaludin NA. Career Planning Indicators of Successful TVET Entrepreneurs. Sustainability. 2023; 15(8):6629. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086629

Chicago/Turabian StyleMuridan, Natasha Dora, Mohamad Sattar Rasul, Ruhizan Mohamad Yasin, Ahmad Rosli Mohd Nor, Rose Amnah Abd. Rauf, and Nur Atiqah Jalaludin. 2023. "Career Planning Indicators of Successful TVET Entrepreneurs" Sustainability 15, no. 8: 6629. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086629