Developing a Digital Business Incubator Model to Foster Entrepreneurship, Business Growth, and Academia–Industry Connections

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background

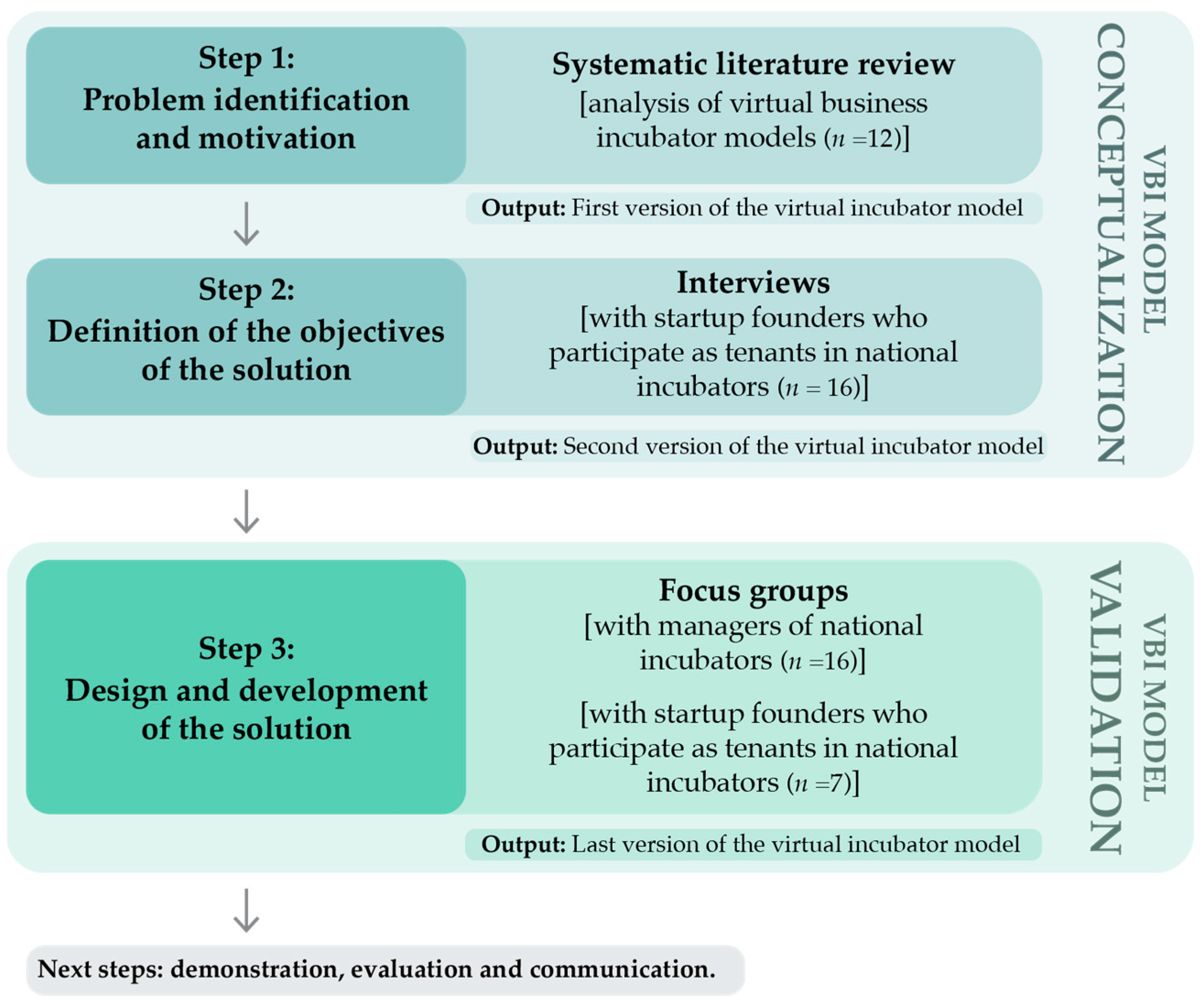

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participant Sampling

3.2. Research Instrument and Procedure

3.3. Data Treatment and Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Participants’ Profiles

4.2. Mapping of Iterations to the Virtual Business Incubator Model

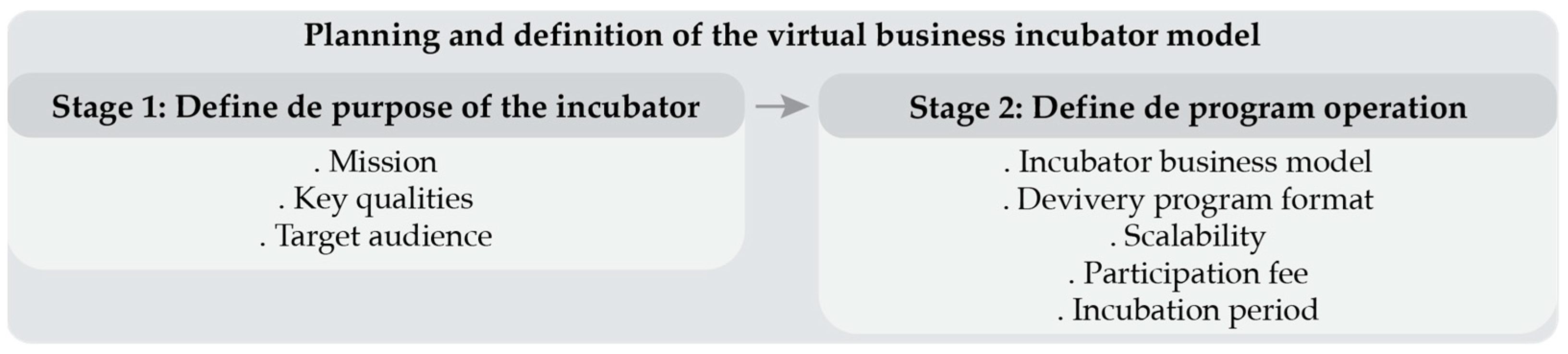

4.3. The Digital Business Incubator Model

4.3.1. Purpose of the Incubator

“A digital incubator has the potential to reach a global audience, so by defining it, you can filter from the beginning applications coming from entrepreneurs from whom the ecosystem is not interested and to whom the incubator is not aimed”(M-2)

4.3.2. Program Operation

“The relationship between these types of structures and the entrepreneurs has to do with points of connection between both sides: the more these connections are, the stronger it makes the relationship and easier it is to support tenants, which is generally not an easy relationship to develop”(M-7)

4.3.3. Communication Strategy

“It is a good way to create a problem-solving mindset and can be excellent to evaluate entrepreneurs’ ideas generation capacity, build a rapport with them, and select candidates to join the incubator later”(M-7)

“Social media have helped us a lot growing and reaching other geographies and contexts. It helps with the brand activation and boosts the incubator’s visibility”.

4.3.4. Application Stage

“We want to receive good applications, so people must think in advance about particular questions related to their projects, at least about the basic things of running a business. Therefore, our form is already developed in this sense”.

“We have to encourage entrepreneurship, of course, but not everyone can be an entrepreneur. If a person does not have the right profile and characteristics, we are contributing to the failure and another company that will go bankrupt. If they do not have resilience and the skills, no matter how good the project is, there is a huge risk that it won’t go anywhere”(M-10)

“Sometimes it is really difficult to understand who has a business project that will effectively have the capacity to develop and scale, and who is using the incubation program for leaving their country, to have tax benefits, or getting a visa, among other issues”(M-8)

4.3.5. Participants’ Selection

“It is during that stage that people tend to lose motivation most easily because they have the ideas and the whole concept. They can visualize the project and put it in the right context but do not know where to go next, how to open a company, and so on”(F-3)

“Incubating entrepreneurs with business ideas and startups already in advanced stages promotes a very informal network, which is extremely fruitful and allows the sharing of innumerous experiences, that ends up being very enriching for everyone”.

4.3.6. Onboarding Process

“Not all entrepreneurs have the same type of needs to launch the same type of business. Each project and each entrepreneur has her/his own path”(M-3)

“It makes perfect sense that the mentor is someone who fits well with the project and the company being created”(F-6)

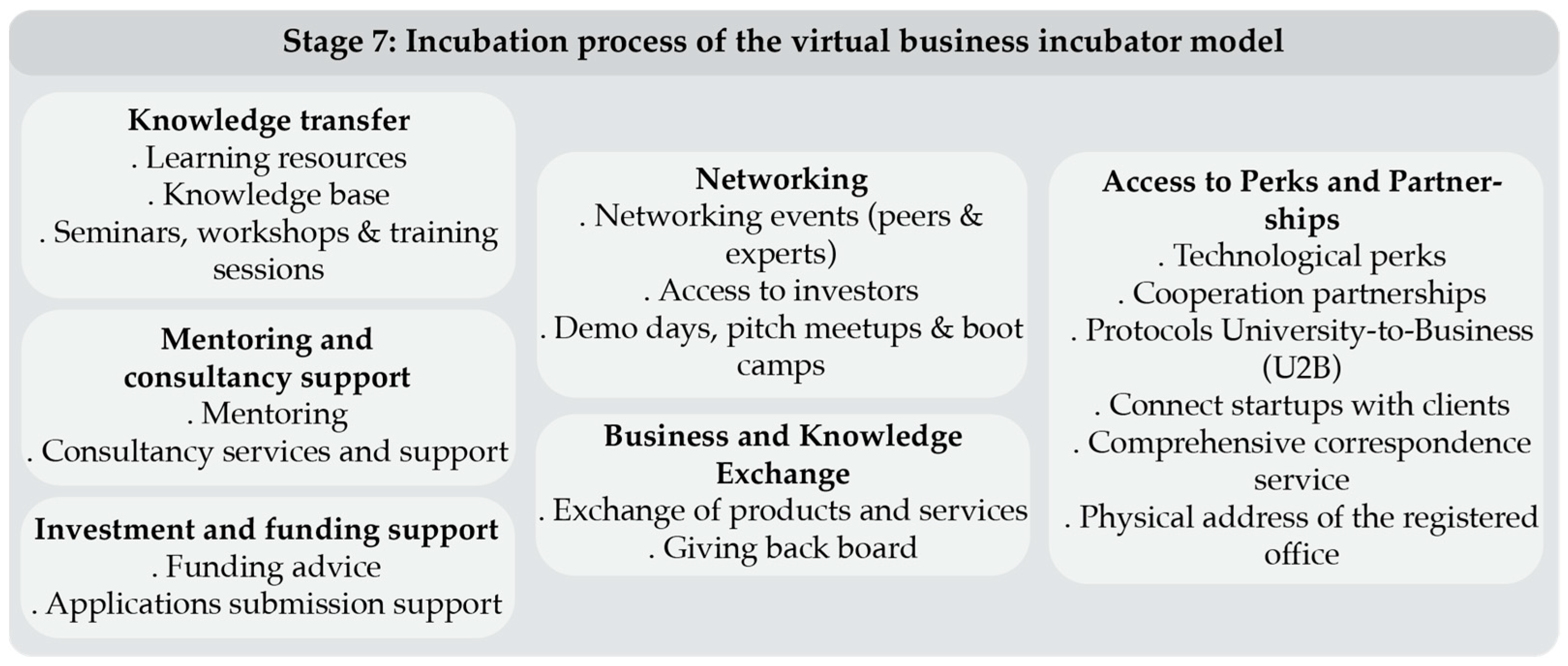

4.3.7. Incubation Process

Knowledge Transfer

- Learning resources directed to tenants’ skills development (e.g., business structure and business plan, minimum viable product, marketing, sales, finance, tax, accounting, and how to pitch, among others) can be provided asynchronously. They can be structured into specific modules to be completed during a certain period of time, including expected goals to attain at the end of each one. These resources should also be combined with meetings with mentors to validate new developments and progress to the following stages. This way, “everyone can be more or less aligned throughout the incubation process” (F-6). Specifically concerning the content related to entrepreneurial development, incubator managers state that the aim of these should be educational, but should not substitute professional assistance required for very specific and sensitive topics to be accomplished (e.g., trademark or patent registration, legal and accountability, among others). As advised by M-5: “Sensitive topics can lead to legal responsibilities, so it is benefic to provide information about them to a certain point, and then entrepreneurs should consult a professional”;

- Several founders and incubator managers agreed that a knowledge base should also be made available. It was suggested that the incubator should allow a cooperative curatorship of content, such as videos, podcasts, books, series, and documentaries, to encourage and support tenants’ professional and personal development. As explained by F-7: “Having access to this type of content enriches us a lot on a professional and personal level. It gives us many extra tools that are complementary to what we are trying to do”;

- Additionally, incubator managers showed interest in having access to a knowledge base like this one, given the remarkable potential to share good practices, “because together we are stronger and if everyone shares what they have, it can be much faster to help each other” (M-10);

- Seminars, webinars, training sessions, and workshops should also be promoted by involving the various incubator stakeholders during virtual or hybrid sessions, and made available to be watched asynchronously afterward. Focus group participants mentioned the importance of assessing tenants’ needs and expectations before organizing these sessions so that they can be more fruitful: “Because we all expect different things, and it should be understood what the majority of incubatees need at a certain time. In my case and many others, this assessment was never done, and then people do not attend the events because there are things that do not fit our entrepreneurial journey” (F-3);

- Another suggestion was to promote problem presentation seminars—i.e., invite representatives of several economic sectors to talk about the challenges, trending needs, and their current investment agenda—so entrepreneurs could adapt their products or services to other businesses that they did not know about: “Our products can have an almost immediate and super useful application in a sector area that we simply do not know and have a Eureka moment” (F-5);

- Still, regarding these events, participants called attention to the fact that several entrepreneurs have parallel jobs when starting their businesses, so it is also important to consider this aspect when organizing synchronous events.

Mentoring and Consultancy Support

- By having dedicated mentors (previously matched), experts can regularly supervise and advise tenants’ work development. Focus group participants recommended that virtual incubators should invest in progressively building a private network of mentors from multidisciplinary fields, “aiming at the best source of information, support, and qualification of incubatees” (M-12). This aspect is of extreme relevance given that tenants “have different needs in different moments” (M-9), but it is also central to keep the mentor–entrepreneur matchmaking as a focal mechanism during the entire incubation process because “Mentors must be aligned with entrepreneurs and have interest in their projects to help them” (M-10);

- Accessing complementary consultancy services and support (such as legal and accountancy, technological, marketing, intellectual property, brand registration, communication, risk management, and product or services development support, for instance [47]) should also be facilitated through the virtual incubator. It was stressed by founders and incubator managers that, depending on the incubator team dimension and expertise, offering several consultancy services in-house over outsourcing them has advantages, such as facilitating and speeding up processes and benefiting the internal ecosystem, while helping to contribute to the economic and financial sustainability of the incubator. According to M-8’s experience: “We rely on professors and researchers to offer some consultancy services and only subcontract services from external partners when we are unable to do it”;

- Nonetheless, a usual practice followed by incubator managers concerns recommending tenants to contact external partners, which, according to founders, “do not offer any price advantage for incubatees” (F-3), which “for a company that is starting, without the capacity to spend so much money, it is an unaffordable financial burden” (F-6). Thus, our model proposes that virtual incubators should consider this aspect and try to negotiate ways to offer competitive and accessible prices for their tenants.

Access to Perks and Partnerships

- Technological perks are important for the development of digital businesses. Some examples include Amazon services, Stripe, Miro, Microsoft for startups, and Google services, among others. It was mentioned that a strategy of offering a growing number of perks would benefit entrepreneurs entering the incubator since “The fee they pay is nothing compared to the set of perks they have access to. We started with 5 perks, and at the moment, we offer more than 40” (M-7);

- Cooperation partnerships should also be progressively developed based on tenants’ needs, such as with research units and FabLabs, and with other incubators. Participants also suggested that developing partnerships with other incubators would benefit the entrepreneurial ecosystem in which the virtual incubator is inserted, and allow the exchange of experience and contacts with other players;

- Protocols focused on a university-to-business (U2B) approach were identified by participants as furthering knowledge exchange, technology transfer, professional internships, and promoting employment. However, incubator managers participating in this study informed us that their incubators lacked offering similar protocols. Founders also explained their interest in U2B protocols: “There are several opportunities to develop interesting university projects in startups, and students and graduates can work on several tasks” (F-5), and “this link would benefit both incubated companies and university students and graduates” (F-4);

- The connection of potential clients with startups should also be considered a perk included in the fee. This subdimension was proposed to help startups succeed, especially during their initial stages. This could be accomplished by trying to facilitate important contacts that entrepreneurs cannot complete, and also by promoting incubated startups’ services or products in online contexts;

- Offering a comprehensive correspondence service to notify, forward, digitize, or collect company mail was another recommended aspect agreed upon by participants. This is remarkably important in the case of virtual business incubators because “It is the first thing that our tenants look for in a virtual incubation because they need to access important mail that arrives through physical correspondence” (M-4);

- Lastly, virtual incubators should allow tenants to use a physical address for the registered office. This perk is fundamental to “entrepreneurs being able to establish their companies legally” (M-3), but “they could only use the address officially after signing the incubation contract” (M-4).

Business and Knowledge Exchange

- Including the perks and services offered by the incubated startups as part of the general incubators’ set of resources would promote business exchanges between tenants. A practical example of this exchange was provided: “If I want to make a website, I’d rather pay another incubated company than an external one that no longer needs this leverage. Providing other entrepreneurs will offer a competitive price is a win-win exchange” (F-6). Concerning this aspect, some managers advised that “the role of the incubator is to promote and foster these business exchanges, but not determine rules” (M-8), meaning that business details and deals should be treated directly between incubatees;

- Making a “giving back board” available, where volunteer tenants can list their areas of expertise or subjects in which they believe they can help other entrepreneurs and become reference persons to provide specific help and support. Having this dimension in a virtual incubator is considered to be extremely useful because “some problems that new incubatees have at the moment were already overtaken by senior entrepreneurs” (M-16), and also given that “My experience showed me that there are several people who are interested in giving back to the community and helping other entrepreneurs” (F-4).

Networking

“Direct contact between people, even if it is sporadic, is what allows the creation of durable bonds between entrepreneurs and other actors that can support their ventures”(M-3)

- For networking events with a particular focus on socialization and promoting access to peers and experts, it was suggested to invite incubated entrepreneurs and recognized founders of startups outside the community to share their experiences. Moreover, inviting experts from several business areas is also important to “Foster connections with specialists in specific areas, who can help us to reconsider specific points of our businesses” (F-6);

- In this case, it was suggested that tenants’ needs at the moment should be assessed so that the events could be most fruitful to them;

- The same applies to events directed to access potential investors. These persons or funding organizations must be selected in accordance with the business sectors and development stages of the incubated startups because “I receive multiple calls for events with investors, but when I start reading them, they are rarely directed to my business area. And this also happens to other founders I know. We are all very busy, and wasting time on useless events is exhausting” (F-3);

- Promoting demo days, pitch meetups, and boot camps involving various stakeholders can allow for expanding the network and enabling new business opportunities. It was agreed that the organization of these types of events should not only be directed to the incubators’ community, but some should be open to the general public as well, so entrepreneurs can communicate their products and services while sharing knowledge and fostering possible collaborations.

Investment and Funding Support

- Inform and advise tenants about public and private funding opportunities aligned with their business sectors and the development stage of their startups. Providing this kind of curated information was highlighted as extremely positive by the founders: “Otherwise, there will be multiple entrepreneurs interested in discovering more about a funding opportunity and then realizing that it does not fit their company, which is a waste of time and energy for everyone” (F-7);

- However, both founders and managers recognized that this curation requires extra effort and is time-consuming, although some managers informed that their incubators follow a similar approach: “We help founders to understand which program is most recommended for their specific cases, to understand the steps they have to follow, and we clear up to a certain extent any questions they have” (M-15);

- Support for applying to funding opportunities was also suggested as an additional service that virtual incubators could provide. According to the focus group participants, this practice is not usual in their incubators, given the multiple resources and particularities it entails. However, they recognize it can benefit tenants while contributing to the economic and financial sustainability of the incubator itself, apart from its market positioning. The only participating manager whose incubator provides this kind of support advised that it also requires a very knowledgeable and dedicated team, and even so, “It is difficult to match a startup in a certain stage and to operate in a determined sector with the incentive programs. It is much information, and the diversity is huge, so we feel this is one of the most difficult parts to add value” (M-7);

- Given this reason, a suggestion to offer tenants this kind of support without overloading the incubator team is to subcontract this service to specialized companies.

4.3.8. Digital Tools

- An official website to allow potential tenants and other stakeholders to learn about the incubator’s purpose and the program operation’s dimensions. This website can also support the incubator’s application stage dimension by making available an online application form to be filled out by entrepreneurs aiming to apply to incubation;

- Learning management systems enable great resources to help in knowledge transfer through synchronous and asynchronous possibilities by integrating multimedia content and facilitating sharing and collaboration. Participants agreed that asynchronous content should consider interactive and gamified approaches to enhance tenants’ knowledge acquisition and overall experience during this stage;

- Video conferencing tools could also be used to: conduct applicants’ interviews; during online and synchronous knowledge transfer moments, such as webinars, workshops, and training sessions; to facilitate meetings with mentors and consultancy activities; to promote online networking events, demo days, pitch meetups or boot camps; to provide support related to investment and funding; to facilitate business and knowledge exchange between tenants; and during the incubator’s communications to the external community. Participants identified that the most common video conferencing tools they use for these purposes were Zoom, Google Meet, Skype, and Webex;

- As already discussed, a knowledge base would facilitate a cooperative curatorship of content (videos, podcasts, books, series, and documentaries, among others) and their sharing to encourage and support tenants’ professional and personal development. The Notion tool was suggested to easily allow management of and access to this information by tenants, incubator managers, and other interested stakeholders;

- A shared folder with documents should also be provided. As stated by participants, during the incubation process, it is important that entrepreneurs can access financial- and business-related documents that are transversal to support their ventures’ development;

- Forums and online group channels were recommended for facilitating communication, sharing experience, and providing mutual support, among other possibilities, in addition to helping tenants grow networking connections and new development opportunities. For instance, forums could be used to build and constantly update the knowledge base with answers to frequently asked questions. Moreover, this can be used to implement the “giving back board”, where volunteer entrepreneurs can list their areas of expertise and subjects to help other entrepreneurs. It was suggested that the most active volunteers could receive a badge recognizing their effort and that other tenants could recommend them based on a start voting approach, for example, as ways to improve the users’ overall experience. Digital platforms such as Slack and Discord were referred to as preferential ones based on participants’ experience;

- Group messaging for instant contacts was stressed as crucial by founders and managers during the entire incubation process. It facilitates stakeholder communication, event scheduling, and the solution of urgent issues, to mention a few examples. WhatsApp and Telegram were mentioned as the most-used by participants in this study;

- Using email for sending newsletters was highlighted as an appropriate tool to communicate important information to the broad community, including forthcoming events and news sharing. It can also be used, for instance, as a way to spread assessment surveys to evaluate tenants’ needs and expectations regarding experts, peers, or topics they would like to know more about in future events;

- Additionally, emerging ICT solutions could also be explored to run virtual incubators. Metaverse [57] is a hot topic regarding further research on its impact on business and society, which still lacks understanding as to how it can support incubation processes, and what new interactive and gamified approaches could be adopted to influence users’ experiences and enhance the overall incubation process, among other subjects.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Practical Contributions

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zahra, S.A.; Wright, M. Understanding the Social Role of Entrepreneurship. J. Manag. Stud. 2016, 53, 610–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansone, G.; Andreotti, P.; Colombelli, A.; Landoni, P. Are Social Incubators Different from Other Incubators? Evidence from Italy. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 158, 120132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ririh, K.R.; Wicaksono, A.; Laili, N.; Tsurayya, S. Incubation Scheme in Among Incubators: A Comparative Study. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Manag. 2020, 17, 2050052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratinho, T.; Henriques, E. The Role of Science Parks and Business Incubators in Converging Countries: Evidence from Portugal. Technovation 2010, 30, 278–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutte, F.; Direng, T. Incubation of Entrepreneurs Contributes to Business Growth and Job Creation: A Botswana Case Study. Acad. Entrep. J. 2019, 5, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Aerts, K.; Matthyssens, P.; Vandenbempt, K. Critical Role and Screening Practices of European Business Incubators. Technovation 2007, 27, 254–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamine, W.; Mian, S.; Fayolle, A.; Wright, M.; Klofsten, M.; Etzkowitz, H. Technology Business Incubation Mechanisms and Sustainable Regional Development. J. Technol. Transf. 2018, 43, 1121–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mian, S.; Lamine, W.; Fayolle, A. Technology Business Incubation: An Overview of the State of Knowledge. Technovation 2016, 50–51, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimaldi, R.; Grandi, A. Business Incubators and New Venture Creation: An Assessment of Incubating Models. Technovation 2005, 25, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls-Nixon, C.L.; Valliere, D.; Singh, R.M.; Chavoushi, Z.H. How Incubation Creates Value for Early-Stage Entrepreneurs: The People-Place Nexus. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2022, 34, 868–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodorakopoulos, N.; Kakabadse, N.; McGowan, C. What Matters in Business Incubation? A Literature Review and a Suggestion for Situated Theorising. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2014, 21, 602–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruneel, J.; Ratinho, T.; Clarysse, B.; Groen, A. The Evolution of Business Incubators: Comparing Demand and Supply of Business Incubation Services Across Different Incubator Generations. Technovation 2012, 32, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauwels, C.; Clarysse, B.; Wright, M.; Van Hove, J. Understanding a New Generation Incubation Model: The Accelerator. Technovation 2016, 50–51, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Walsh, G.S.; Li, C.; Baskaran, A. Exploring Technology Business Incubators and Their Business Incubation Models: Case Studies from China. J. Technol. Transf. 2021, 46, 90–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardani, S.I.; Widayani, A.; Rachmawati, I.; Widayani, A.; Latifah, N.; Normawati, R.A. Business Incubator Development Model on Campus to Encourage the Growth of Young Entrepreneurs. Asian J. Manag. Entrep. Soc. Sci. 2023, 3, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.; Fattani, M.T.; Ali, S.R.; Enam, R.N. Strengthening the Bridge Between Academic and the Industry Through the Academia-Industry Collaboration Plan Design Model. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 875940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moody, D. Using the World Wide Web to Connect Research and Professional Practice: Towards Evidence-Based Practice. Inf. Sci. Int. Emerg. Transdiscipl. 2023, 6, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joergensen, M. Working with Industry: Stories of Successful and Failed Research-Industry Collaborations on Empirical Software Engineering. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE/ACM 5th International Workshop on Conducting Empirical Studies in Industry (CESI), Buenos Aires, Argentina, 23–23 May 2017; pp. 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, R.; Massoudi, M.; Jindal, R. Na Alumni-Based Collaborative Model to Strengthen Academia and Industry Partnership: The Current Challenges and Strenghts. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 2263–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausberg, J.P.; Korreck, S. Business Incubators and Accelerators: A Co-Citation Analysis-Based, Systematic Literature Review. J. Technol. Transf. 2020, 45, 151–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indiran, L.; Khalifah, Z.; Ismail, K. A Historical Review of Business Incubation Models. In Proceedings of the 4th International Seminar on Entrepreneurship and Business, Penang, Malaysia, 17 October 2015; pp. 733–751. [Google Scholar]

- Bergek, A.; Norrman, C. Incubator Best Practice: A Framework. Technovation 2008, 28, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, G.; Bock, A.J. The Business Model in Practice and Its Implications for Entrepreneurship Research. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2011, 35, 83–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit, R.; Zott, C. Value Creation in E-Business. Strateg. Manag. J. 2001, 22, 493–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, R.; de Carvalho, J.V.; Teixeira, S.F. Towards a Unified Business Incubator Model: A Systematic Literature Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristin, D.M.; Chandra, Y.U.; Masrek, M.N. Critical Success Factor of Digital Start-Up Business to Achieve Sustainability: A Systematic Literature Review. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Information Management and Technology (ICIMTech), Semarang, Indonesia, 11–12 August 2022; pp. 583–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M.J.; Grantham, C.E. The Virtual Incubator: Managing Human Capital in the Software Industry. Res. Policy 2000, 29, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzafestas, S. The Art and Impact of Physical and Virtual Enterprise Incubators: The Greek Paradigm. In Open Lnowledge Society: A Computer Science and Information Systems Manifesto; Lytras, M.D., Carroll, J.M., Damiani, E., Avison, D., Vossen, G., OrdonezDePablos, P., Eds.; Communications in Computer ans Information Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; Volume 19, pp. 549–559. [Google Scholar]

- Joita, A.C.; Carutasu, G.; Botezatu, C.P. Technology and Business Incubator Centers—Adding Support To Small And Medium Enterprises in the Information Society. In Economic World Destiny: Crisis and Globalization? Section V: Economic Information Technology in the Avant-Garde of Economic Development; Lucian Blaga, University of Sibiu: Sibiu, Romania, 2010; pp. 107–115. [Google Scholar]

- Pirker, J.; Guetl, C. Iterative Evaluation of a Virtual Three-Dimensional Environment for Start-Up Entrepreneurship in Different Application Scenarios. In Proceedings of the 2012 15th IEEE International Conference on Interactive Collaborative Learning (ICL), Villach, Austria, 26–28 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Guetl, C.; Pirker, J. Implementation and Evaluation of a Collaborative Learning, Training and Networking Environment for Start-Up Entrepreneurs in Virtual 3D Worlds. In Proceedings of the 2011 14th IEEE International Conference on interactive Collaborative Learning (ICL), Piestany, Slovakia, 21–23 September 2011; pp. 58–66. [Google Scholar]

- Ciocoiu, C.N.; Colesca, S.E.; Pacesila, M.; Burcea, S.G. Designing a Weee Virtual Eco-Innovation Hub: The Vision of the Academic and Research Environment. In Proceedings of the 8th International Management Conference: Management Challenges for Sustainable Development, Bucharest, Romania, 6–7 November 2014; Popa, I., Dobrin, C., Ciocoiu, C.N., Eds.; International Management Conference. Editura Ase: Bucaresti, Romania, 2014; pp. 1128–1140. [Google Scholar]

- Unal, O.; Afsarmanesh, H.; Angelov, S. An Agile Innovation Framework Supported through Business Incubators. In Collaborative Systems for Smart Networked Environments; Camarinha Matos, L.M., Afsarmanesh, H., Eds.; IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; Volume 434, pp. 307–316. [Google Scholar]

- Agostinho, C.; Lampathaki, F.; Jardim-Goncalves, R.; Lazaro, O. Accelerating Web-Entrepreneurship in Local Incubation Environments. In Proceedings of the Advenced Information Systems Engineering Workshops, CAISE 2015, Stockholm, Sweden, 8–9 June 2015; Persson, A., Stirna, J., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Business Information Processing. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; Volume 215, pp. 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawil, N.M.; Halim, A.A.; Ramlee, S.; Arsad, N. Enhancing Small Medium Enterprises Opportunity through Online Portal System. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Advances in Electrical, Electronic and Systems Engineering (ICAEES), Putrajaya, Malaysia, 14–16 November 2016; pp. 631–635. [Google Scholar]

- Elia, G.; Margherita, A. A Collective Intelligence Platform for Developing Technology Entrepreneurship Ecosystems. In Creating Technology-Driven Entrepreneurship; Carlucci, D., Spender, J.C., Schiuma, G., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2016; pp. 195–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, B. Oulu Edulab: University-Managed, Interdisciplinary Edtech Incubator Program from Finland. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Innovation and Entrepreneurship (ICIE 2017), Cyberjaya, Malaysia, 26–27 April 2017; Aziz, K.A., Ed.; Acad Conferences Ltd.: Reading, UK, 2017; pp. 140–144. [Google Scholar]

- Luik, J.; Ng, J.; Hook, J. Virtual Hubs Understanding Relational Aspects and Remediating Incubation. In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference On Human Factors in Computing Systems, Glasgow, UK, 4–9 May 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Data Corporation. Startup & Entrepreneurial Ecosystem Report, Portugal 2022; International Data Corporation: Lisbon, Portugal, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- International Data Corporation. Startup & Entrepreneurial Ecosystem Report, Portugal 2021; International Data Corporation: Lisbon, Portugal, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hennink, M.M. Focus Group Discussions: Understanding Qualitative Research; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dresch, A.; Lacerda, D.P.; Antunes, J.A.V. Design Science Research. In Design Science Research: A Method for Science and Technology Advancement; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 67–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, S.T.; Smith, G.F. Design and Natural Science Research on Information Technology. Decis. Support Syst. 1995, 15, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peffers, K.; Tuunanen, T.; Rothenberger, M.A.; Chatterjee, S. A Design Science Research Methodology for Information Systems Research. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2007, 24, 45–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, S.T.; Storey, V.C. Design Science in the Information Systems Discipline: An Introduction to the Special Issue on Design Science Research. MIS Q. 2008, 32, 725–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayazit, N. Investigating Design: A Review of Forty Years of Design Research. Des. Issues 2004, 20, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, R.; Teixeira, S.F.; de Carvalho, J.V. Comfortable but Not Brilliant: Exploring the Incubation Experience of Founders of Technology-Based Startups. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Incubator Network. Available online: https://www.rni.pt (accessed on 2 December 2022).

- Van Rijnsoever, F.J.; Eveleens, C.P. Money Don’t Matter? How Incubation Experience Affects Start-up Entrepreneurs’ Resource Valuation. Technovation 2021, 106, 102294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, P. The Entrepreneurship Research Challenge; Edward Elgar Publishing Limited: Cheltenham, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chavoushi, Z.H.; Nicholls-Nixon, C.L.; Valliere, D. Mentoring Fit, Social Learning, and Venture Progress During Business Incubation. J. Appl. Bus. Econ. 2020, 22, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, D. Realising Potential: The Impact of Business Incubation on the Absorptive Capacity of New Technology-Based Firms. Int. Small Bus. J. 2014, 32, 897–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preece, J.; Rogers, Y.; Sharp, H. Interaction Design: Beyond Human-Computer Interaction, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: West Sussex, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Miro. Miro: The Visual Collaboration Platform for Every Team. Available online: https://www.miro.com (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis. In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology, Vol 2: Research Designs: Quantitative, Qualitative, Neuropsychological, and Biological; Cooper, H., Camic, P.M., Long, D.L., Panter, A.T., Rindskopf, D., Sher, K.J., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; pp. 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.; Kanbach, D.K.; Krysta, P.M.; Steinhoff, M.M.; Tomini, N. Facebook and the Creation of the Metaverse: Radical Business Model Innovation or Incremental Transformation? Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2022, 28, 52–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reit, T. Knowledge Transfer in Virtual Business Incubators. Probl. Zarządzania-Manag. Issues 2022, 20, 173–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scillitoe, J.L.; Chakrabarti, A.K. The Role of Incubator Interactions in Assisting New Ventures. Technovation 2010, 30, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackett, S.M.; Dilts, D.M. Inside the Black Box of Business Incubation: Study B—Scale Assessment, Model Refinement, and Incubation Outcomes. J. Technol. Transf. 2008, 33, 439–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackett, S.M.; Dilts, D.M. A Systematic Review of Business Incubation Research. J. Technol. Transf. 2004, 29, 55–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdam, M.; McAdam, R. The Networked Incubator: The Role and Operation of Entrepreneurial Networking with the University Science Park Incubator (USI). Int. J. Entrep. Innov. 2006, 7, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.J.; Thornberry, C. On the Structure of Business Incubators: De-Coupling Issues and the Mis-Alignment of Managerial Incentives. J. Technol. Transf. 2018, 43, 1190–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, S.; Blomquist, T. The Temporal Dimensions of Business Incubation: A Value-Creation Perspective. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. 2020, 21, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harima, A.; Periac, F.; Murphy, T.; Picard, S. Entrepreneurial Opportunities of Refugees in Germany, France, and Ireland: Multiple Embeddedness Framework. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2021, 17, 625–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenger, E. Communities of Practice and Social Learning Systems. Organization 2000, 7, 225–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, L.E.; Spreitzer, G.M.; Bacevice, P.A. Co-Constructing a Sense of Community at Work: The Emergence of Community in Coworking Spaces. Organ. Stud. 2017, 38, 821–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Focus Groups by Participants | Focus Group Code | Participant Abbr. * | Age Group | Sex | Educational Background | Incubator Code | Role in Incubator |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Focus groups with startup founders (n = 3) | Focus Group A | F-1 | 35–44 | M | Post-graduation in photography | I-1 | Startup co-CEO |

| F-2 | 35–44 | F | Master’s degree in theater studies | I-1 | Startup co-CEO | ||

| F-3 | 35–44 | F | Ph.D. in food technology | I-2 | Startup CEO | ||

| Focus Group B | F-4 | 27–34 | M | Master’s degree in informatics engineering | I-2 | Startup CEO | |

| F-5 | 27–34 | M | Master’s degree in mathematics | I-2 | Startup CEO | ||

| Focus Group C | F-6 | 35–44 | F | Ph.D. in cellular biology | I-2 | Startup CEO | |

| F-7 | 27–34 | M | Master’s degree in entrepreneurship and innovation | I-1 | Startup CEO | ||

| Focus groups with incubator managers (n = 5) | Focus Group D | M-1 | 35–44 | F | Bachelor’s degree in architecture | I-3 | Director of economic development |

| M-2 | 35–44 | M | Master’s degree in educational technologies | I-3 | Senior technician of economic development | ||

| M-3 | 35–44 | M | Bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering | I-4 | Director of marketing and innovation | ||

| Focus Group E | M-4 | 35–44 | M | Master’s degree in entrepreneurship and innovation | I-5 | Manager of administration | |

| M-5 | 35–44 | M | Master’s degree in information and enterprise systems | I-6 | Project manager | ||

| M-6 | 35–44 | M | Bachelor’s degree in business management | I-7 | Chair of the Board of Directors | ||

| Focus Group F | M-7 | 45–54 | M | Bachelor’s degree in informatics engineering | I-8 | Incubator CEO | |

| M-8 | 45–54 | F | Master’s degree in business management | I-9 | Chair of the Board of Directors | ||

| Focus Group G | M-9 | 27–34 | M | Master’s degree in economics | I-10 | Project manager | |

| M-10 | 55+ | F | Master’s degree in management | I-10 | Chair of the Board of Directors | ||

| M-11 | 55+ | M | Post-graduate in public management and administration | I-11 | Incubator Director | ||

| M-12 | 55+ | F | Bachelor’s degree in sociology | I-11 & I-12 | Technical advisor and consultant | ||

| Focus Group H | M-13 | 45–54 | M | Master’s degree in educational sciences | I-13 | Board advisor | |

| M-14 | 35–44 | M | Bachelor’s degree in civil engineering | I-11 | Senior technician | ||

| M-15 | 27–34 | F | Post-graduate in human resources management | I-14 | Incubator Coordinator | ||

| M-16 | 45–54 | F | Master’s degree in business management | I-15 | Incubator Coordinator |

| Focus Groups by Participants | Focus Group Code | Participants | Topics Modified | New Topics Included | Topics Removed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Focus groups with startup founders (n = 3) | Focus Group A | F-1, F-2 & F-3 |

|

| No topics were removed during the focus group session. |

| Focus Group B | F-4 & F-5 |

|

| No topics were removed during the focus group session. | |

| Focus Group C | F-6 & F-7 |

|

| No topics were removed during the focus group session. | |

| Focus groups with incubator managers (n = 5) | Focus Group D | M-1, M-2 & M-3 |

|

| No topics were removed during the focus group session. |

| Focus Group E | M-4, M-5 & M-6 |

|

|

| |

| Focus Group F | M-7 & M-8 |

|

|

| |

| Focus Group G | M-9, M-10, M-11 & M-12 |

|

| No topics were removed during the focus group session. | |

| Focus Group H | M-13, M-14, M-15 & M-16 |

|

| No topics were removed during the focus group session. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vaz, R.; de Carvalho, J.V.; Teixeira, S.F. Developing a Digital Business Incubator Model to Foster Entrepreneurship, Business Growth, and Academia–Industry Connections. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7209. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097209

Vaz R, de Carvalho JV, Teixeira SF. Developing a Digital Business Incubator Model to Foster Entrepreneurship, Business Growth, and Academia–Industry Connections. Sustainability. 2023; 15(9):7209. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097209

Chicago/Turabian StyleVaz, Roberto, João Vidal de Carvalho, and Sandrina Francisca Teixeira. 2023. "Developing a Digital Business Incubator Model to Foster Entrepreneurship, Business Growth, and Academia–Industry Connections" Sustainability 15, no. 9: 7209. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097209

APA StyleVaz, R., de Carvalho, J. V., & Teixeira, S. F. (2023). Developing a Digital Business Incubator Model to Foster Entrepreneurship, Business Growth, and Academia–Industry Connections. Sustainability, 15(9), 7209. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097209