1. Introduction

Words such as competence, skills, and proficiency in the chosen area of study are considered key outcomes of the teaching-learning process. A relatively recent addition to this list is the term

21st-century skills. Before exploring the concept of 21st-century skills further, it would be useful to first understand why are these being considered and what were the skills under focus prior to the surfacing of the idea of 21st-century skills. In this regard, from the perspective of teaching-learning process, traditionally there was emphasis on ‘generic skills or core competences or the general transferable skills in teaching and learning’ [

1] or ‘graduate attributes’ [

2], which were considered the necessary pre-requisites for future personal life of students and their contribution to societal growth [

1].

While the need to prepare future-ready citizens continues to be the key aim of the educational system across the world even now, the demands imposed by change in work requirements, technological environment and the general approach to life have made it necessary for all stakeholders to put greater emphasis on defining more clearly what future-readiness means. In this regard, prior studies have noted the need for the curriculum and the entire education system to change in response to the changing socio-politico-economic milieu across the world which is more dynamic and unstable (e.g., [

3,

4]). In fact, multiple stakeholders in the education system including teachers, governmental institutions, researchers and prospective employers accept the need for students to learn skills that will hold them in good stead in the changing world. With the result, policy proposals related to reforming the educational system to prepare students for navigating the changing world call for inculcating 21st century skills in them [

5]. This is how the discussion on twenty-first-century skills has come in focus in research and practice (e.g., [

6,

7]).

Since cultivation of 21st century skills have been acknowledged as the key outcome of education at all levels, it is essential to understand what these skills imply. Interestingly, literature has defined 21st-century skills from different perspectives. Some reports describe these skills as the ability to exhibit high-level reasoning, comprehend content and solve problems through application and transfer of knowledge ([

8,

9]). Prior studies also interpret them as skills for learning, creativity, critical thinking, ability to collaborate and use ICT (Information and Communication Technologies) as required [

10]. Expanding the list, the Partnership for 21st Century Skills mentioned the following skills: skill in core subject areas and 21-first-century themes, skills related to life and career, creativity, critical thinking, skills to form collaboration, communication skills, technology use skills and information and media skills [

11]. Another study [

12] lists technical, communication, information, collaboration, creative, problem-solving and critical thinking skills as key 21st-century skills.

Multiple organisations have established frameworks for 21st-century skills, proposing combinations of skills and competencies. In 1997, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) developed a framework for conceptualising competences, launching the Definition and Selection of Competences (DeSeCo) program, which later served as a theoretical foundation for Programme for International Student Assessment [

13]). Based on DeSeCo, skills were categorised into the following broad themes: (a) information as both product and source, (b) effective communication, (c) ethics, and (d) social impact dimension of communication [

14]. Another grouping of 21st-century skills was proposed by [

15] in their pioneering work as (a) Learning and innovation skills, (b) information, media, and technology skills, and (c) life and career skills. Continuing the effort, The European Reference Framework built on the outcomes of the OECD-DeSeCo program to identify eight key competences in 2006: learning to learn, communication, mathematics scientific and technological competence, digital competence, cultural, social, and civic competences, and entrepreneurship [

16]. Similarly, The US Partnership for 21st Century Learning (P21), established in 2001, proposed a framework to clarify student outcomes and learning support systems, which includes the following skills: core subjects and 21st-century themes, life and career, communication, collaboration, creativity, critical thinking, and information, media, and technology skills [

11].

In addition to the efforts made by various bodies and institutions to formalise competencies and skills, many organisations also took the initiative for the same. For instance, Cisco, Intel, and Microsoft collaborated to establish the Assessment and Teaching of 21st-century skills (ATC21S) group for better integration of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) and educational assessment. This group defined 21st-century skills as a way of thinking, way of working, tools for working, and living in the world [

10]. More recently, providing inputs for education systems, the UNESCO’s Report (Transversal Competencies in Education Policy and Practice Report, 2015) suggested a range of skills and competencies that should be included in curricula policy and curriculum, including critical thinking and creativity, working with others, character, global citizenship, health and wellbeing ([

17], p. 1).

Having established the importance of cultivating 21st-century skills in students, it is also essential to deliberate on how this objective can be achieved effectively. Review of reports, policy documents and research articles reveal that society, regulators, researchers and other stakeholders consider teachers’ role to be vital in the implementing educational reforms and curricular changes (such as inclusion of 21st-century skills) introduced from time to time. At the same time, existing scholarship categorically states that teachers need to be supported to effectively discharge their role of implementing changes and reforms (e.g., [

18,

19,

20]), else the initiatives are likely to fail. This is testified by the fact that despite the inclusion of 21st-century skills in curriculum [

21], these are still not focussed on in the classroom teaching-learning process [

22] primarily due to lack of training support for teachers [

23]. Other studies also observe that on account of lack of proper professional development and teacher education, cultivation of the requisite 21st-century skills in students can remain below expectation. For instance, in the context of STEM education, ref. [

24] noted that if teachers’ knowledge and understanding is deficient, students learning will also remain limited. Reference [

25] supported this view by providing significant empirical evidence. These findings underscore the need for serious relook at teacher education programmes. Further, since teachers are increasingly required to model their teaching-learning approach in such a way that it develops 21st century skills in their students [

26], it is very important to have proper training mechanisms in place for both in-service and pre-service teachers. Indeed, there is an urgent need to ensure that teachers are trained effectively so that they are successful in supporting and promoting skill development in their students [

27].

The authors note that despite acknowledgment of the importance of teacher education to catalyse development of 21st-century skills in students, the research focus on various aspects of teachers’ professional development and training has remained rather narrow. Given the criticality of inculcation of 21st-century skills in students for society as a whole, limited research insights imply lack of actionable inputs for design of effective teacher education programmes. Thus, this study calls for immediate research in the area and supports the call by organizing and critically evaluating the past literature to make sense of the accumulated knowledge and guide future research by identifying the gaps that need to be addressed. Specifically, the study uses systematic literature review (SLR) approach to identify, analyse and present the state-of-the-art on teacher education in the context of 21st-century skills. SLR approach is recognized as a robust and effective approach toward literature review and has been used by a large number of recent studies in different contexts (e.g., [

28,

29,

30]).

The broad objective of the SLR is to suggest future research paths to enrich the extant knowledge in the area. The study proposes to achieve these objectives through three research questions:

- (1)

What is the research profile of the studies published in this area?

- (2)

What are the key themes that prior studies have focussed on?

- (3)

What are the open gaps in findings and how can these be addressed?

The three questions have been answered by identifying 55 relevant studies and critically evaluating them through descriptive and thematic analysis.

2. Materials and Methods

This study utilized the SLR methodology to review the extant literature related to teacher education and 21st-century skills. While prior reviews have executed the SLR methodology with many variations, yet an overview of the recently published studies (e.g., [

31,

32]) reveals that three steps necessarily need to followed to execute any SLR effectively. In this regard, the first step is to plan the review where the search protocol is laid down in consonance with the objectives of the study. The second step is extraction of data and screening it for relevance by applying the specified search protocol and stringent filtering. The third, and the final step is analyzing the identified studies to extract descriptive statistics for research profiling and coding the findings to uncover emergent themes and identify open gaps in prior literature. The authors followed all three steps systematically.

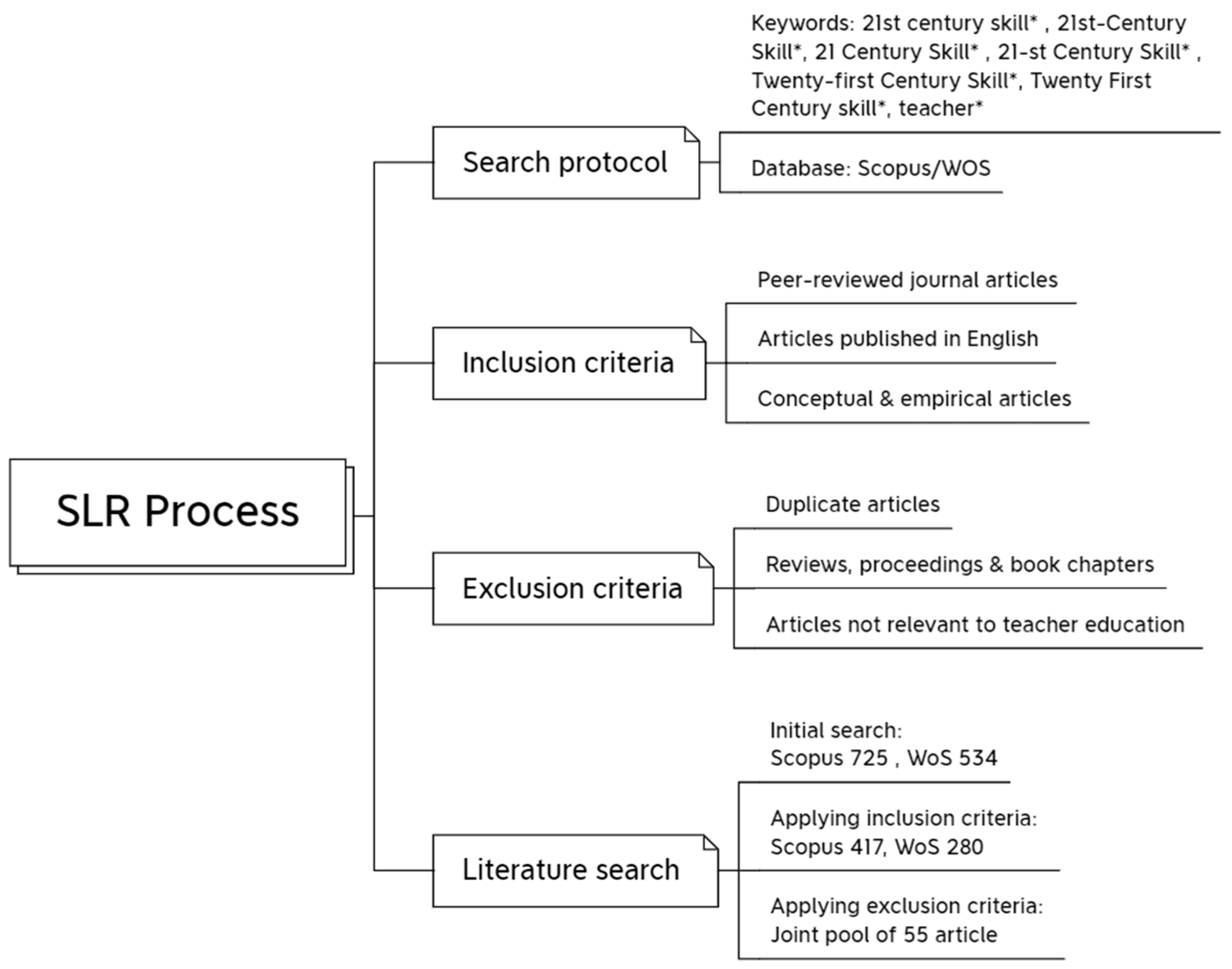

To begin with, the authors developed a robust search protocol which encompassed identification of digital databases for searching the relevant literature, specifying the keywords and search strings to be used on these databases, and delineating the inclusion and exclusion criteria for screening of studies. Herein, the authors decided to confine search to two popular databases—Scopus and Web of Science (WoS). The authors then searched the string ‘teaching 21st-century skills’ on google scholar, and examined the studies found to determine the final set of keywords to be used. As a result, following search string was executed on Scopus: (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“21st century skill*” OR “21st-Century Skill*” OR “21 Century Skill*” OR “21-st Century Skill*” OR “Twenty-first Century Skill*” OR “Twenty First Century skill*”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (“teacher*”)), to yield initial set of 725 results. Similarly, following search string was executed on WoS: ((“21st century skill*” OR “21st-Century Skill*” OR “21 Century Skill*” OR “21-st Century Skill*” OR “Twenty-first Century Skill*” OR “Twenty First Century skill*”) (Topic)) AND (“teacher*”) (Topic) to yield initial set of 534 results. The timespan specified was all years.

Next, the authors applied the specified inclusion and exclusion criteria to screen the initial set of results by referring to recent studies (e.g., [

29]). First, applying the inclusion criteria of considering only journal articles published in English language, 417 documents from Scopus and 280 from WOS were taken forward for further evaluation. At this stage, the first exclusion criterion was applied to eliminate prior reviews from amongst the shortlisted documents. As a result, a total of 28 documents, tagged as reviews were removed from the downloaded lists. Not all these reviews were focused on teacher education. The authors identified the relevant reviews and examined them to ensure that the present study makes a meaningful contribution, going beyond extending what has already been undertaken. The second exclusion criterion was applied to exclude duplicate studies available on both databases. As a result, 201 studies were removed. At this stage, a joint pool of 468 studies was obtained. From this pool, 260 articles were removed since these were reviews, proceedings, and book chapters or articles not relavant to teacher education and 208 studies were taken forward for further screening.

Herein, the authors checked titles and abstracts of 208 to establish the relevance of each article and apply the third exclusion criterion of eliminating irrelevant studies. Wherever the relevance of the study was not immediately apparent from the abstract, the authors read full articles to determine the same. As a result, 55 relevant articles were selected and the rest 153 were excluded since these had only a passing reference to 21st-century skills or teacher education. With this the second step of the execution of SLR was completed.

At the final and third stage, the authors thoroughly read full text of all 55 studies to ensure their congruence with the objective of the review. Thereafter, information was extracted to present the research profile of these articles, followed by manual content analysis to code the findings and identify their thematic foci. The findings of third step are presented in the next two sections. All steps followed in this study are presents in

Figure 1.

Research Profiling of Selected Studies

Descriptive details related to statistical aspects such as volume of publication offer useful insights for future research. Due to this, the authors examined the short-listed studies to present details related to year-wise publications, geographical location, publication source, and publishing houses. In this regard,

Figure 2 showcases the trend of publication in the area. The pattern is quite erratic, but in general there is a rising trend, revealing increasing research interest. But the number of studies, when seen in comparison to the size and variety of schools and colleges across the world, is extremely low. This supports the present study’s call for more research in the area.

With regard to the geographical context of research, as exhibited in

Figure 3, it is apparent that research interest has been skewed towards United States and overall, only 21 countries have had some research in the area. Given that there are about 200 countries in the world, the limited geographical variety of insights provided by the existing literature related to teacher education and 21st-century skills lends further support to this study’s call for urgent research output in the area.

Looking at publication sources presented in

Figure 4, the authors observes that the studies have been published mainly education specific journals, particularly those with a technology slant. Future researchers can benefit from this information and find more receptive publication sources for their research in the area as far is scope is concerned. Next,

Figure 5 indicates that most of the major publishing houses have published research in the area, which highlights its significance.

3. Results

The authors thoroughly evaluated the shortlisted studies to understand their focus and findings. In this regard, the study undertook vigorous thematic analysis to understand the thematic foci of the selected studies. Since the orientation of this study was to assess the current state of teaching-learning of 21st-century skills from teachers’ point of view, the themes were classified to bring forth the perspective of teachers related to the impediments faced and the support needed to develop 21st-century skills in their students. In order to ensure that the thematic analysis process was rigorous, the study followed a multi-pronged strategy for identifying the themes. To begin with, the authors examined each study independently and completed first-level coding based on the research objective. Herein, the reviewed studies were categorized under two broad themes: (i) Upskilling and reskilling of in-service teachers in 21st-century skills, and (ii) Professional development of pre-service teachers and 21st-century skills. Since the objective and perspective of this SLR was clearly defined, there was no inter-coder dispute or disagreement. Thereafter, the authors jointly evaluated the first level coding and identified sub-themes within these two themes and determined suitable nomenclature for each sub-theme. The three sub-themes under the theme upskilling and reskilling of in-service teachers in 21st-century skills are:

training initiatives for teaching skill upgradation,

teachers’ experiences in teaching 21st-century skills and

teachers’ perceptions and skill assessment.

The three sub-themes under the theme professional development of pre-service teachers and 21st-century skills are:

pedagogical approaches to train future-ready teachers,

technology-based teaching-learning of 21st-century skills, and

experience, competence and proficiency in 21st-century skills.

Finally, the authors sought feedback of two professors with expertise in teacher education. They made some suggestions regarding how each theme should be presented and discussed. The authors then proceeded to undertake a more specific coding and analysis of studies identified under each theme and sub-theme. Themes and sub-themes are presented in

Figure 6. The relevant findings of reviewed studies are discussed below.

3.1. Upskilling and Reskilling of In-Service Teachers in 21st-Century Skills

The key findings related to each sub-theme are discussed below.

3.1.1. Training Initiatives for Teaching Skill Upgradation

This sub-theme synthesizes the academic findings related to the type of professional development trainings and activities undertaken to promote 21st-century skills of in-service teachers, the design needs to enhance the efficacy of such programmes, the learning outcomes for teachers and the effectiveness of potential approaches to training. These initiatives comprise some interventions, models, tools, resources developed and approaches such as peer mentoring, learning at work, as exhibited in

Table 1.

To begin with, ref. [

33] observed that as a part of developing 21st-century skills, teachers need to promote and nurture the ability of students to pursue self-regulated learning. Thus, teachers’ education programmes should have tools that train them on how to imbibe student-centred teaching approaches that promote autonomous learning. Contributing actionable insights in this regard, ref. [

34] discussed an innovative blended model of teachers’ professional learning that can help shift their pedagogical orientations and support effective inclusion of various elements of 21st-century skills into the teaching-learning process.

Spotlighting another key aspect of effective training, ref. [

35] emphasized the importance of incorporating teachers’ point of view in the design of professional development programmes targeted towards enhancing 21st-century skills aligned with the envisaged educational reforms. Scholars have also examined how the duration of the training programme can affect in-service teachers’ learning. In this regard, providing evidence in support of large-scale, broad-based and long-term professional development programmes for teacher inservicing related to 21st-century skills, ref. [

36] showed that at the end of three years of such initiative, noticeable changes occurred in the knowledge level, use of ICT, assessment methods and pedagogical approach of teachers. The study also suggested that the number of hours for which teachers undertook professional development programme had notable effect on their learning.

Existing scholarship has also acknowledged the role of collaborative learning in promoting in-service teachers’ effectiveness in developing 21st-century skills in their students. For instance, on the subject of training in-service teachers for imparting student-centred teaching that facilitates development of 21st-century skills [

37], presented teacher peer mentoring as a potential tool. Giving useful inputs for efficacious execution of such an approach, the study suggested that for this method to be successful, the mentors need adequate structures and support to properly discharge their responsibility of guiding other teachers.

Expressing concern about limited context-specific insights on teaching approaches and effectual ways of promoting development of 21st-century skills in students, ref. [

38] underscored the necessity of measuring teaching-learning practices and processes which facilitate the development of these skills at different levels such as secondary, primary, and pre-school levels. The study also argued in favour of the need to re-conceptualize the entire approach to evaluating and training teachers to ensure enhancement in their 21st-century teacher skills.

In addition to examining broad teaching contexts, some past studies have focussed on specific aspects of teacher education to facilitate the required proficiency in 21st-century skills. These include STEM education, integration of specific devices in teaching-learning process, e-learning, language learning etc. Since STEM integration is an important part of developing 21st-century skills in students, scholars have noted that it is important to have well-thought programmes that can promote teachers’ ability to design, develop and implement effective curriculum. In this regard, ref. [

39] revealed the effectiveness of collaborative approach such as community of practice in improving teachers’ ability to undertake interdisciplinary teaching and overcoming the subject discipline silos. Further contributing specific inputs for teacher education/professional development programmes [

24], contended that at present, design and technology are considered as interdisciplinary educational constructs which are not given a status equal with other STEM courses, and underscored the need to visualize these within STEM context for more effective teaching of 21-st century skills.

In the case of need to integrate specific devices such as iPad in classroom teaching, ref. [

40] examined the training needs of teachers for both, the initial technology integration in classroom setting and ensuring that the usage is sustained year after year. The findings of the study underscored collaborative learning from peers and work time as most effective ways of professional development in comparison to one-to-one coaching or training with large groups. It is pertinent to note here that although e-learning is considered to be an important part of imparting 21st-century skills, yet as [

41] argue, the approach of different countries to teacher education for using e-learning differs in orientation and focus. For instance, in Singapore peer-learning communities are considered important for teacher development, whereas China emphasises self-directed teacher development. This implies a need to understand peculiarities and requirements of each country separately while developing professional development programmes for teachers to hone their technology-related skills.

Shifting attention to an important yet under-explored aspect, ref. [

42] examined the content and outcome of the Global Academic Essentials Teacher Institute and related interventions implemented to enhance 21st-century skill competencies of in-service teachers who taught social studies and foreign languages. Providing useful inputs for future training programmes, the study revealed that the most appreciated part of this institute’s approach were the demonstration activities integrating subject content and pedagogical inputs for incorporating the required technologies.

3.1.2. Teachers’ Experiences in Teaching 21st Century Skills

Skill-building and future preparedness has always been the focus of education. Teachers’ on-going efforts to develop 21st-century skills in students have also received some attention, with schools and colleges introducing courses and activities to inculcate these skills in students. The studies reviewed under this sub-theme have examined the experiences of teachers in this regard. The experiences documented herein vary from positive to negative outcomes resulting from the efforts to enhance students’ 21st-century skills through self-directed learning, explicit social-emotional learning, multi-disciplinary orientation, technology integration and STEM education, as presented in

Table 1.

To begin with, ref. [

43] examined the outcome of implementing a mandatory multidisciplinary learning module at school level to reveal the challenges that hinder the achievement of anticipated learning. The study noted that despite positive collaborative outcomes, many problems emerged due to the amorphous definition of goals and vagueness around course content. Moving on, acknowledging that self-directed and self-regulated learning are important parts of 21st-century student skill-set, ref. [

44] contended that teachers need to understand as well as facilitate the two, despite the challenges that may exist. In this regard, the study examined the experiences of secondary school teachers to suggest ways of promoting self-directed learning which include imparting lucid instructions, preparing systematic and comprehensive learning material, and dealing with differences in the ability of students to undertake self-directed learning.

Supporting the idea that emotional and social skills also need explicit teaching for which teachers need to be at the forefront, ref. [

45] examined the perception of primary school teachers who were part of a project that encompassed programmes on emotional literacy, development of creative thinking and training of teachers to act on as well as mediate students’ learning. Analysis of qualitative data collected from teachers confirmed the significant impact of the project on their personal as well as professional development, and its contribution to the improvement in classroom environment, behaviour of students and their relationships with each other.

When the discussion is on 21st-century skills, technology cannot be ignored. Indeed, we are living in era of technology and there is no disputing its role in the efficacious development of 21st-century skills in students. This is further testified by the findings of a study by [

46] which examined teachers’ experiences of integrating web 2.0 tools in their teaching. The study confirmed the positive response of students to lessons in which such tools were implemented. In a similar vein, ref. [

47] examined teachers’ experiences to highlight the importance of technology-based teaching-learning approach in the foundation phase. In this regard, the study noted that to promote student learning outcomes aligned with the required 21st-century skills, there is an urgent need to enhance technology-related skills and pedagogical acumen of teachers to enable them to integrate technology-based teaching and learning approach in their classroom interactions. However, technology-based teaching comes with its own set of challenges. For instance, although all stakeholders in the education system understand the importance of data driven decision making, yet as [

48] observed, school-level reform initiatives that include implementation of data-informed instructional planning by teachers are hindered by multiple barriers. Specifically, the study revealed that such implementation is limited to a few subjects only, and it creates a lot of stress since multiple initiatives are required for its smooth implementation.

Moving to broader perspective, in agreement with the long-standing observation that the students can be better equipped with 21st-century skills through STEM-related teaching, ref. [

49] reviewed the experiences of teachers and findings related to using robots in school-level STEM education. Noting the importance of such an initiative, the study provided curricular and operational inputs for the introduction of robotics in educational process at the school level. In another study acknowledging the importance of STEM education in inculcating 21st-century skills in students, ref. [

50] examined the experiences of elementary school teachers with regard to the use of mathematical modelling for teaching. The study results supported mathematical modelling as a right approach for developing communication skills, critical thinking, collaborative orientation and creativity in students. Ref. [

51] also provided evidence to support the effectiveness of mathematics in enhancing students’ critical reasoning and promoting enquiry in primary science. Offering a tangible takeaway, the study deliberated on how teachers can contribute by properly designing and implementing tasks aligned with STEM education.

3.1.3. Teachers’ Perceptions and Skill Assessment

The studies evaluated under this sub-theme have brought forth a variety of elementary yet pertinent issues that range from teacher awareness of what comprises 21st-century skills, their perception of expertise required to impart such skills to gaps that the in-service teachers perceive in their own preparedness to ensure such skill-building in students. Scholars suggest that teachers’ own competence in 21st-century skills are important to enable them to catalyse their students’ proficiency in these skills (e.g., [

26]). Not surprisingly, most of the studies reviewed herein focussed on some or the other aspect of using digital technology while teaching 21st-century skills. In this regard, most of reviewed studies have discussed teachers’ attitude towards usefulness of information and communications technologies (e.g., [

52]), as can be observed in

Table 1.

Underscoring the deep link between 21st-century skills and technology, ref. [

53] Willis et al. (2019) examined potential factors that can enhance teachers’ use of ICT in classroom. Focussing on K-12 educators, the study observed that teachers own competence in using ICT and their view that technology can help increase positive outcomes for students drove their purposeful approach to ICT implementation in teaching as an integral part of their pedagogy. Offering more evidence to support the undeniable link between technology and teaching of 21st-century skills [

54], undertook an examination of various aspects of teachers’ skills related to digital information. The study found that these skills varied with age of teachers and the extent of their digital activity, with the two affecting the skill levels in opposite manner. Professors teaching at higher education level also recognize the positive effect of ICTs on enhancing students’ 21st-century skills, particularly in areas such as communication and critical thinking [

55].

Despite the acknowledged importance of digital technology in teaching at all levels, there are many grassroot problems. One such problem is lack of awareness, as observed by [

56] in their study that examined the beliefs of teachers and use of technology. The findings revealed that the teachers had concerns related not only to embedding technology in the teaching-learning process but also about what all skills actually come in the ambit of 21st-century skills. Teachers also did not comprehend 21st-century skills in students that can be developed through disconnected classroom activities [

57]. Another problem that the past research has highlighted is that even in developed countries, there is a rural-urban digital divide in terms of teachers’ access to and knowledge of ICTs depending on their geographical location. Ref. [

58] discussed the same issue with regard to project-based learning of teachers through Web 2.0, documenting the existence of such divide both at physical access as well as teaching-related usage access levels.

A larger problem in this regard is the limited extent of ICT usage in teaching. Noting this, ref. [

59] revealed that despite the emphasis laid on first language writing and the integration of the suitable ICT tools into its’ teaching by education systems geared to impart twenty-first century skills, the assimilation of these tools is limited. To elaborate, the study found that although the first language teachers acknowledge the value of ICT and also positively perceive their own competence to use these tools, yet they make limited use of the tools for teaching first language writing. Rather, they tend to use it more often for assessing their students. In addition, past studies have noted the inhibiting/facilitating role of subjective factors in teachers’ use of digital technology for teaching at different levels. For instance, ref. [

55] observed that professors’ perceptions may limit their usage of ICT. Similarly, ref. [

60] found that teachers’ attitude, self-efficacy and their perceived usefulness of technology affected their intentions to emphasise digital literacy in classrooms. Also, ref. [

61] revealed that behavioural beliefs related to the value of digital literacy for students and normative beliefs related to fulfilling social expectation drove teachers’ integration of technology in their teaching.

Creativity, which is acknowledged as a key 21st-century skill, has also been examined by past studies to some extent. For instance, ref. [

62] found that most teachers are quite unaware of varied nuances of creativity, and that they do not use creative approach while teaching. At the same time, the study identified curriculum over-weighed by content, exam-driven approach, and limited hours for teaching a course as inhibitors of creative approach to teaching, and teachers’ own motivation as the facilitating factor. Interestingly, and quite practically, the study identified students and technology as both facilitating and inhibiting factors. Presenting an interesting discussion of the skills and approaches that experienced teachers from diverse areas, extending from science, visual and performing arts, psychology and counselling, school administration to languages and mathematics perceive that all teachers should have, ref. [

63] provided useful strategies for enhancing organic creativity in students.

3.2. Professional Development of Pre-Service Teachers and 21st-Century Skills

The studies reviewed under this theme provide a close look into various aspects and nuances of research on professional development of pre-service teachers to prepare them for their future roles. To make the past contributions more relatable and clearer, the authors synthesised the prior findings on pre-service teachers and 21st-century skills by categorizing them into three sub-themes:

Section 3.2.1,

Section 3.2.2 and

Section 3.2.3.

The key findings related to each sub-theme are discussed below.

3.2.1. Pedagogical Approaches to Train Future-Ready Teachers

As the profile of students is changing and becoming more cosmopolitan by the day, the education systems are facing challenge to transform design of teachers’ education programmes. Thus, with the objective of training student teachers to have a learning trajectory aligned with the need to cultivate 21st-century skills in their future students, it is essential to reconceptualize pedagogical approaches for pre-service teacher education to include self-directed learning, reflexivity, and collaborative learning in community settings [

64]. From a pedagogical standpoint, blended teaching-learning approach is also quite effective in enhancing achievements of pre-service teachers from both the academic perspective as well as their own twenty-first century skills [

65], as presented in

Table 2.

Enriching the available insights on pedagogical approaches for professional development of pre-service teachers to increase their proficiency in developing higher order thinking skills in students, ref. [

66] examined the effectiveness of problem-based learning method supported by Web 2.0 tools. The study found that the method and related tools enhanced the academic performance and critical thinking skills of student teachers, making them feel better prepared for their future roles. Making another useful pedagogical contribution, ref. [

67] developed and successfully deployed a program designed to improve computational thinking skills of future teachers. The program, which largely comprised computer-aided and robotic activities, was perceived positively by the pre-service teachers since their problem solving and other thinking skills improved noticeably after completing their training.

Showcasing the pedagogies that can be successful in an online environment, ref. [

68] uncovered the usefulness of the student-created video as an active learning activity that can increase student teachers’ STEM knowledge, enhance their perceived self-efficacy, stimulate their engagement with learning and foster their 21st-century skills. Ref. [

6] also provided evidence supporting the significant role of active learning experiences in improving professional competence of student teachers in terms of a teacher’s role in school and society.

Focussing on an important yet under-explored dimension of professional development of pre-service teachers to prepare them for successful teaching careers, ref. [

69] examined the benefits that student teachers can derive from gaining authentic researcher experiences during their pre-service training. The findings of the study indicated that the pre-service teachers valued the research experiences that they got during their training since these experiences enhanced their competence in 21st-century skills. In a similar vein, ref. [

70]) examined the effectiveness of a research-based approach to enhance information and media literacy of pre-service teachers, wherein they were trained to systematically search, evaluate, and use journal articles and relevant Websites. The study revealed the critical role of formative assessment in increasing proficiency of student teachers. Contributing further to the discussion on pedagogical variety, ref. [

71] examined the use of novel pedagogy of emancipatory education for professional development of pre-service teachers to confirm that the approach was effective in equipping the student teachers with the required 21st-century skills such as higher-order thinking.

Making a very important point about pedagogical choices, ref. [

72] provided the learners’ perspective that can help in design and choice of appropriate pedagogy. In this regard, the study mapped the expectations of student teachers from their professional development course for improving their 21st-century skills. The findings revealed that the pre-service teachers connected their learning outcomes with the tasks they perceived they would be required to perform as teachers. Highlighting another important aspect of pedagogical choices, ref. [

73] observed that the success of any pedagogical tool used for teacher education is dependent on the ecosystem it is implemented in. In this context, the study observed that professional development of pre-service teachers through professional learning communities (PLC) can be quite diverse, depending on their participation in PLC and institutional organising themes.

3.2.2. Technology-Based Teaching-Learning of 21st-Century Skills

Technology, digital literacy, ICT tools etc. are recognized as key parts of 21st-century skills teaching-learning process. In fact, most pre-service teachers link 21st-century skills with communication, technology, information literacy, and digital citizenship [

74]. Taking cognizance of the same, past studies have examined various aspects of technology-based teaching readiness and perceptions of pre-service teachers (see

Table 2). For instance, ref. [

75] examined digital game design experience of pre-service teachers, using mathematics teaching as context. Findings of the study showed considerable impact of game-building exercise on attitude of pre-service teachers towards the usefulness of gaming as a pedagogical tool. In a similar vein, ref. [

76] examined the outcome of a multisite research project for teaching pre-service art teachers digital game design. The findings indicated that while most student teachers appreciated learning value of game design, yet some of them had negative attitude towards it. Some also lacked the proficiency to handle the technology aspect of computer-generated imagery. A similar concern was also captured by [

77] in their study investigating readiness of pre-service teachers in the context of computer-assisted language teaching-learning. The results of data analysis revealed that the student teachers agreed that integrating digital technologies fostered a dynamic classroom environment, and they perceived themselves competent in use of ICTs. Despite this, the student teachers did not seem motivated enough to integrate technology in their teaching. Furthermore, they admitted to existence of several barriers that could impede use of ICT tools in language teaching such as lack of time, school policies and support from senior colleagues. Finally, through a study that examined pre-service teachers’ perceptions about use of cell phones in classroom settings, ref. [

78] reinforced the point that despite acceptance of digital technology as a key catalyst in learning, pre-service teachers are confused about how to draw it benefits and avoid its pitfalls. The study revealed that while the pre-service teachers appreciated the instructional benefits provided by cell phones, they were extremely concerned about the disruptions the devices may cause as well as the opportunities for cheating that they can create.

3.2.3. Experience, Competence and Proficiency in 21st-Century Skills

Pre-service teachers who are currently honing the teaching skills by undertaking teacher education programmes have the responsibility to cultivate 21st-century skills in their students. A good beginning point for teachers to inculcate these skills in their future students is to first increase their own proficiency in these skills. Due to this, under this sub-theme the authors have reviewed the past studies that have examined student teachers’ own experience, competence and proficiency in 21st-century skills. The key nuances of these studies are presented in

Table 2. In this regard, ref. [

79] addressed the basic question of whether the pre-service teachers were equipped with 21st-century skills or not by exploring it through variables such as the foreign language level, gender, teacher education programme, and cumulative grade point. The results promisingly indicated high scores on 21st-century skills, with only foreign language level having a significant effect. The study thus brought forth the importance of advanced level of proficiency in foreign language. Highlighting the importance of technology in the context of 21st-century skills yet again, ref. [

80] examined the drivers of pre-service teachers’ digital literacy. The results of the study revealed that digital literacy of student teachers in the area of science was impacted by two sets beliefs—conceptions of teaching and scientific epistemological beliefs. Thereby, the study provided an interesting input on the importance of understanding student teachers’ belief systems to impart more effective teacher education.

Bringing other skills, in addition to digital literacy, to forefront, ref. [

81] examined student teachers’ perception about their 21st-century skills represented by collaboration and teamwork, learning strategies, and knowledge and attitude towards integration of ICT tools in teaching. The study revealed that while the pre-service teachers ranked themselves high in terms of competence in first two skills, they perceive their knowledge of using ICT tools in education to be comparatively lower. Advancing the discussion on the levels of specific 21st-century skills, ref. [

82] presented a longitudinal look at the perception of pre-service teachers about their 21st-century skills and dispositions. Focussing on ICT-related skills, collaborative dispositions and learning skills, the study revealed that while the latter two remain at the same level, the skills to use ICT show significant improvement annually. Interestingly, the three skills appeared as distinct factors all through the training, with negligible correlation.

Table 2.

Professional development of pre-service teachers and 21st-century skills (Second Theme).

Table 2.

Professional development of pre-service teachers and 21st-century skills (Second Theme).

| Sub-Theme | Level * | Context | Approaches/Tools ** | Skills | Objective | Studies |

|---|

| Pedagogical approaches to train future-ready teachers | Early childhood educators [1]

Elementary school teaching [3]

Primary & secondary school teaching [1]

Religious education

student teachers [1]

Student teachers [5] | Active learning experiences Graduation projects ICT Online educational technology course Practicum experience Professional development Research project ‘21st-century skills, multiple literacies and development of RE teacher education Research-based practice Social studies methods course in teaching certification or dual certification in elementary/bilingual or elementary/special education The teaching principles and methods course in pedagogical training certificate program The curriculum and learning development course

| A classroom experiential model in emancipatory education Active learning approach in an online environment Active learning experiences instrument Blended teaching-learning approach Information and media literacy instruction Problem-based learning method supported by Web 2.0 tools Professional learning communities (PLCs) Professional competences instrument Research studies instrument Skills test related to the knowledge and implementation dimension of computational thinking based The learning by design pedagogical framework The twenty-first-century skills framework

| Accountability for ascertaining desirable educational outcomes Authentic instructional design Collaboration Cooperation with others Critical & creative thinking skills Dialogue skills Ethical commitment teachers’ tasks outside classroom Evidence-based practice Higher order thinking skills Information, media & technology skills Integrative 21st-century skills Judgment in applying differentiating teaching/planning Learning & innovation skills Learning to learn skills Life & career skills Making pedagogical choices Navigate & evaluate digital-age resources Personal knowledge creation Planning learning repertoires Problem-solving skills Professional skills Questioning skills Readiness for multicultural & media education Readiness for teacher professional development Religious literacy Social & interaction skills Teaching competences in classrooms

| Benefit from authentic researcher experiences Effect of a blended teaching-learning approach on academic achievement, long-term learning and twenty-first century skills Effect of a program design developed to provide prospective teachers with computational thinking skills on learners Engage in learning design in a meaningful and collaborative way Ensure learners have sufficient skills to expand their social studies content knowledge through research Examine the impact of problem-based learning activities integrated with Web 2.0 applications on the academic achievement and critical thinking skills of teacher candidates Explore the possibilities and impact of emancipatory education in the preparation of future teachers Exploring the link between organisational capacities and personal dimensions, and how institutional processes shape student-teachers’ use of and professional development in PLCs Impact of active learning methods on student teachers’ professional competences Inform instructional practices of student-created video Student teachers’ expectations to develop competencies

| [6,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73] |

| Technology-based teaching-learning of 21st-century skills | Different departments of an education faculty [1] Teacher-training programs spanning

from the earlier years of compulsory school to upper secondary school [1]

After-degree bachelors of education program [1]

Undergraduate English

teacher education programme [1]

Art teachers [1]

Initial teacher certification

Programs [1] | 21st-century skills in daily & education Changing attitudes toward technology English as a foreign language Incorporate everyday technologies in teaching Secondary mathematics methods course

| | | Experiences of learning through game design Experiences and reactions of participation in digital game design classes Perceptions on of the use of devices in the classroom Readiness in the use of computer-assisted language learning Views about 21st-century skills

| [74,75,76,77,78] |

| Experience, competence and proficiency in 21st-century skills | Science course [1]

Bachelor’s degree studies [1]

First-year [1]

Seniors in various undergraduate

programmes [1]

Starting level of first-year [1]

Undergraduate music education majors [1] | Difference in senior pre-service teachers’ life & career skills Elementary methods course ICT in education National Core Curriculum Student profiles &life satisfaction Student teachers who had already taken certain courses related to the epistemology of science and science teaching methods as well as technology integration

| The Scale for twenty-first-Century Skills and Competencies for Prospective Teachers Science teaching belief system Questionnaire, latent profile analysis (LPA) Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire Project for 21st-century skills

| 21st-century skills Collaboration dispositions Collaboration & teamwork skills Digital literacy skills Knowledge and skills to use ICT in education Strategic learning skills The Partnership for 21st-century learning & innovation skills

| Assessing level of 21st-century skills & causes of variation Examining scientific epistemological beliefs (SEBs) and conceptions of teaching and learning (COTL) Longitudinal perspectives on possible changes in perceptions of 21st-century skills and dispositions Navigating 21st-century skills in lesson planning and field experiences Perceptions of strategic learning skills and collaboration dispositions Perceptions of 21st-century skills, as well as knowledge and attitudes related to ICT

| [79,80,81,83,84] |

Further underscoring the importance of learning skills and collaboration, ref. [

83] examined pre-service teachers’ perceptions about the level of their own strategic learning skills and collaborative dispositions, categorizing them under various profiles. The study also explained the background variables that influenced membership of these profiles. The results revealed five profiles corresponding to perceived level of the two skills wherein anticipated life satisfaction emerged as the most significant variable explaining membership of any profile.

Notably, 21st-century skills in teaching-learning of performing arts has remained a rather underexplored area. Recognizing this gap, ref. [

84] examined how student teachers preparing to be music teachers in future integrate 21st-century skills in lesson planning and field experiences. The study specifically focussed on partnerships for 21st-century learning and innovation skills to reveal how student teachers navigated these skills.

3.3. Theme-Wise Gaps and Future Research Paths

Deep analysis and discussion of themes helped the authors understand the literature closely, enabling them to identify the gaps in literature from the perspective of quality and quantity of research required to improve practical insights for ready reference of multiple stakeholders involved in the teacher education on 21st-century skills.

3.3.1. Gaps in Research on Upskilling and Reskilling of In-Service Teachers in 21st Century Skills and Future Research Paths

In general, the literature on professional development of in-service teachers to improve their competence to cultivate 21st-century skills in their students is narrow, scattered and myopic. Specifically, research related to the type, design and efficacy of various interventions, tools, resources, projects and other approaches to enhance the in-service teachers’ proficiency in teaching-learning process aligned with 21st-century skills is extremely deficient as evidenced from the limited number of approaches mentioned in

Table 1. At the same time, the authors also observe that although in-service teachers are critical drivers for imparting competence in 21st-century skills, yet the literature to understand their skills, experiences, perceptions, attitudes, and factors that motivate them to make efforts to align their teaching with tools that are known to enhance these skills is very limited. Similar, negligible number of studies have focussed on barriers that inhibit teachers from integrating tools and techniques commensurate for developing skills such as creativity, critical thinking, innovation and so on in students. There is a need to give unprecedented momentum to research in the area to ensure that the teacher education programmes that are designed and implemented in different colleges and institutes to upskill in-service teachers are informed by robust findings and not merely an outcome of few meetings of limited number of stakeholders. Taking cognizance of the gaps and the exigency to address them, the authors suggest following research paths (RP) to enrich the available literature in the area:

RP1: How are short-term training programmes more effective in upskilling 21st-century proficiencies of in-service teachers as compared to long-term professional development programmes extending more than a year?

RP2: What are the most effective ways of integrating STEM in developing 21st-century skills such that the teachers follow a more interdisciplinary approach rather than remaining confined to the rigid subject boundaries?

RP3: What are the targeted interventions that can be effective in educating in-service teachers to overcome the implementation challenges they face in teaching 21st-century skills-aligned multi-disciplinary modules?

RP4: What are the specific skills and resources that need to be developed in teachers to enable them to make curricular and pedagogical changes to increase students’ takeaway from STEM courses?

RP5: What are the most time and cost effective ways of enhancing teachers’ awareness of the 21st-century skills which are relevant to the level at which they are teaching?

RP6: What is the perception of teachers about having a supporting teacher to integrate technology in teaching, if digital self-efficacy is an issue?

RP7: Developing a map of key 21st-century skills for each course by involving experienced teachers such that in-service teacher upskilling programmes can be made more customized and relatable, instead of being generic.

RP8: What are the teaching skills and pedagogical tools that teachers should have competence to use if they want to give a seamless learning experience to their students with regard to developing 21st-century skills related to socio-emotional learning?

RP9: How do teachers’ positive perceptions of their own proficiency in various 21st-century skills affect learning outcomes for their students?

RP10: To what extent do in-service teachers correlate their own proficiency in 21st-century skills with their ability to inculcate these skills in their students, going beyond the integration of technology in classroom?

RP11: How does the 21st-century skill requirement of teachers and their effect on students change with the type of subject they teach?

RP12: How can social media be used effectively to enhance teachers’ own 21st-century skills?

RP13: What are the various tools through which in-service teachers’ 21st-century skills can be measured effectively and assessed accurately?

RP14: How do geographic locations and cultural differences affect 21st-century skill proficiency of teachers and their ability to enhance the development of same skills in their students?

3.3.2. Gaps in Research on Professional Development of Pre-Service Teachers and 21st-Century Skills and Future Research Paths

The research on various aspects of professional development of pre-service/student teachers in the context of 21st-century skills is limited as evidenced from the fact that the authors found a total of 22 relevant studies spread across three sub-themes. As a result, the literature is deficient from all dimensions, be it contexts and settings examined, courses considered, pedagogical tools tested for efficacy, insights offered, skills focussed and so on, as presented in

Table 2. Since pre-service teachers are going to shape the coming generation of students, lack of research-grounded understanding of how best they can be prepared for the onerous responsibility they have towards institution, community, society, country and the world at large is quite worrisome. The authors suggest following research paths that can clarify some of the key issues related to pre-service teacher education and provide actionable inputs for programme design and pedagogy:

RP1: What is the relationship between the choice of pedagogical framework and student teachers’ expectations?

RP2: What are the potential ways in which community settings can be used to train students teachers to develop their 21st-century skill teaching-learning competence?

RP3: What are different reflexive pedagogies that can be used to enhance teaching skills of future teachers teaching courses in social science and arts, particularly in developing countries?

RP4: Are active learning experiences more effective in increasing 21st-century skills-related professional competence of pre-service teachers for all courses or only STEM-related courses?

RP5: Does training imparted through blended mode result in better outcomes for student teachers as compared to traditional offline delivery of all modules in a teacher education programme?

RP6: What kind of research-based projects can be effective in providing authentic learning experience to student teachers?

RP7: How does institutional and community orientation affect the design of teacher education programme and the learning outcomes for pre-service teachers?

RP8: How effective is self-directed learning in enhancing high-order thinking skills of student teachers?

RP9: How do the training needs of student teachers in developing countries differ from those in developed countries with respect to increasing competence in technology-based teaching-learning of 21st-century skills?

RP10: How does culture (for example, collective versus individualistic) affect the 21st-century skill-related learning outcomes for pre-service teachers?

RP11: What are the potential 21st-century skill combinations (for example, creativity and critical thinking) that can be cultivated through single digital game designed for imparting education in STEM as well as non-STEM courses?

RP12: How can pre-service teachers’ prior knowledge, creativity and reasoning skills be enhanced to improve their ability to design curriculum and digital games aligned with 21st-century skill development?

RP13: How do the perceptions of pre-service teachers about the use of technological devices such as iPads and ICT tools in classroom vary with their gender?

RP14: How can primary school pre-service teachers be trained effectively to leverage the ‘bring your own device’ initiative for improving students’ 21st-century skills?

RP15: What are the differences in association between beliefs and digital literacy of student teachers in developing versus developed countries, including gender-based insights.

RP16: What are the perceptions of pre-service performing arts teachers about the key 21st-century skills relevant for them to develop in themselves and later in their students?