Internationalisation at Home: Developing a Global Change Biology Course Curriculum to Enhance Sustainable Development

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Context of the Study

2. Methodology

2.1. Case Study Background: Description of the “Global Change Biology” Course, and The Chinese University of Hong Kong

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Student Participation in the Survey and Ethical Considerations

2.4. Survey Design

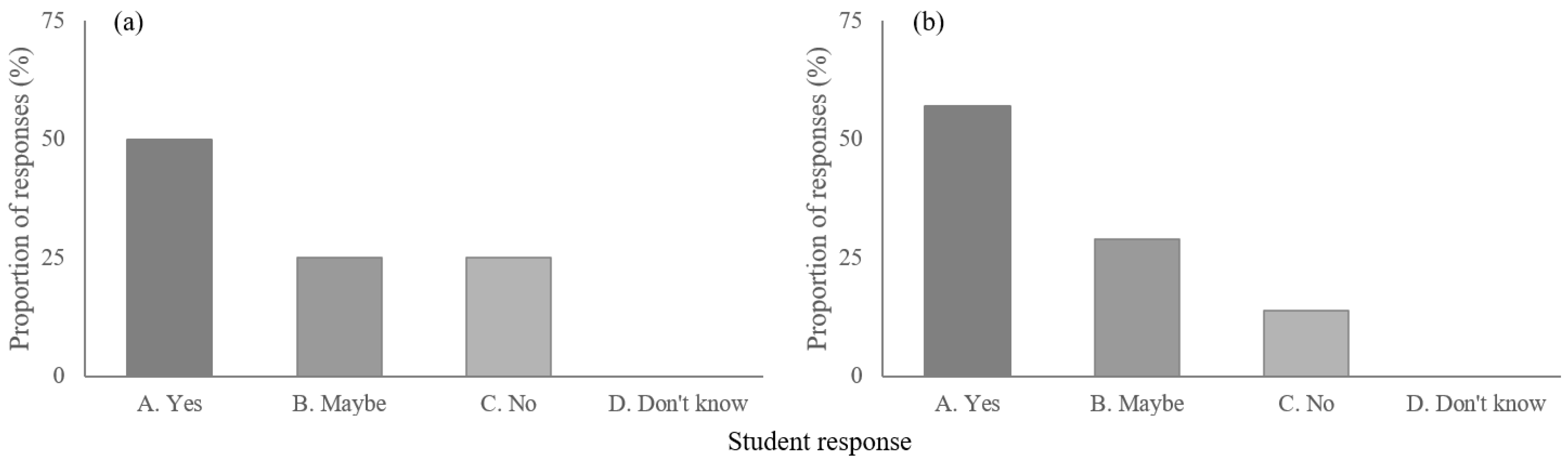

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications of the Findings from This Curriculum Internationalisation

4.2. Enhancing the Success of Future Internationalisation at Home Initiatives

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IPCC. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis; Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Masson-Delmotte, V.P., Zhai, A., Pirani, S.L., Connors, C., Péan, S., Berger, N., Caud, Y., Chen, L., Goldfarb, M.I., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Traub, G.; De la Mothe Karoubi, E.; Espey, J. Indicators and a Monitoring Framework for the Sustainable Development Goals: Launching a Data Revolution for the SDGs; Sustainable Development Solutions Network: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sustainable Development Solutions Network. SDG Academy; SDSN: New York, NY, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.unsdsn.org/sdg-academy (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- McClelland, D.C. Testing for competence rather than for intelligence. Am. Psychol. 1973, 28, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, S.; Pensini, P. Nature-based environmental education of children: Environmental knowledge and connectedness to nature, together, are related to ecological behaviour. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2017, 47, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, N. Practice, problems and power in ‘internationalisation at home’: Critical reflections on recent research evidence. Teach. High. Educ. 2015, 20, 412–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Zhu, C.; Cao, C. An exploratory study of Chinese university undergraduates’ global competence: Effects of internationalisation at home and motivation. High. Educ. Q. 2017, 71, 159–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, L.; Wihlborg, M. Internationalising the content of higher education: The need for a curriculum perspective. High. Educ. 2010, 60, 595–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, S.H.; Newstead, C.; Gann, R.; Rounsaville, C. Empowerment and ownership in effective internationalisation of the higher education curriculum. High. Educ. 2018, 76, 989–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, S. Internationalisation of the curriculum: Challenges and opportunities. J. Perspect. Appl. Acad. Pract. 2015, 3, 50–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braskamp, L.A.; Braskamp, D.C.; Merrill, K. Assessing progress in global learning and development of students with education abroad experiences. Front. Interdiscip. J. Study Abroad 2009, 18, 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, R.; Waters, J. Student Mobilities, Migration and the Internationalization of Higher Education; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Erdei, L.A.; Rojek, M.; Leek, J. Learning alone together: Emergency-mode educational functions of international virtual exchange in times of the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Adult Learn. Knowl. Innov. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, J.L. Geographies of international education: Mobilities and the reproduction of social (dis)advantage. Geogr. Compass 2012, 6, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudzik, J.K. Comprehensive Internationalization: From Concept to Action; NAFSA: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Robson, S. Internationalization at home: Internationalizing the university experience of staff and students. Educação 2017, 40, 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beelen, J.; Jones, E. Redefining Internationalization at Home. In The European Higher Education Area; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 59–72. [Google Scholar]

- Crowther, P. (Ed.) Internationalisation at Home: A Position Paper; European Association for International Education: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, J. Higher Education in Turmoil: The Changing World of Internationalization; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K. Ten Facts About Internationalising Higher Education Online: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly? In Reconfiguring National, Institutional and Human Strategies for the 21st Century: Converging Internationalizations; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 269–289. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, C.D.; Abdullah, D. Internationalisation of Malaysian higher education: Policies, practices and the SDGs. Int. J. Comp. Educ. Dev. 2021, 23, 212–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittelmeier, J.; Rienties, B.; Gunter, A.; Raghuram, P. Conceptualizing internationalization at a distance: A “third category” of university internationalization. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2021, 25, 266–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wihlborg, M.; Robson, S. Internationalisation of higher education: Drivers, rationales, priorities, values and impacts. Eur. J. High. Educ. 2018, 8, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R. China’s strategy for the internationalization of higher education: An overview. Front. Educ. China 2014, 9, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganassin, S.; Satar, M.; Regan, A. Virtual exchange for internationalisation at home in China: Staff perspectives. J. Virtual Exch. 2021, 4, 95–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Zhu, C.; Meng, Q. A survey of the influencing factors for international academic mobility of Chinese university students. High. Educ. Q. 2016, 70, 200–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard-Jones, P.; Sands, D.; Dillon, J.; Fenton-Jones, F. The views of teachers in England on an action-oriented climate change curriculum. Environ. Educ. Res. 2021, 27, 1660–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development: Building a Better Fairer World for the 21st Century; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gifford, R. The dragons of inaction: Psychological barriers that limit climate change mitigation and adaptation. Am. Psychol. 2011, 66, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy, A.; Trumbull, K.; Loh, C. The Impacts of Climate Change in Hong Kong and the Pearl River Delta; Civic Exchange: Hong Kong, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Grothmann, T.; Patt, A. Adaptive capacity and human cognition: The process of individual adaptation to climate change. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2005, 15, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiro, J. Learning interconnectedness: Internationalisation through engagement with one another. High. Educ. Q. 2014, 68, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luxon, T.; Peelo, M. Internationalisation: Its implications for curriculum design and course development in UK higher education. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2009, 46, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trahar, S.; Hyland, F. Experiences and perceptions of internationalisation in higher education in the UK. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2011, 30, 623–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, A.S.; Kennedy, M. Internationalising the student experience: Preparing instructors to embed intercultural skills in the curriculum. Innov. High. Educ. 2012, 37, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Wit, H.; Altbach, P.G. The Impact of COVID-19 on the Internationalisation of Higher Education, Revolutionary or Not? In Global Higher Education during and beyond COVID-19: Perspectives and Challenges; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022; pp. 219–231. [Google Scholar]

- O’Dowd, R. Internationalising Higher Education and the Role of Virtual Exchange; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Caruana, V. Re-thinking global citizenship in higher education: From cosmopolitanism and international mobility to cosmopolitanisation, resilience and resilient thinking. High. Educ. Q. 2014, 68, 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Falkenberg, L.J.; Joyce, P.W.S. Internationalisation at Home: Developing a Global Change Biology Course Curriculum to Enhance Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7509. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097509

Falkenberg LJ, Joyce PWS. Internationalisation at Home: Developing a Global Change Biology Course Curriculum to Enhance Sustainable Development. Sustainability. 2023; 15(9):7509. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097509

Chicago/Turabian StyleFalkenberg, Laura J., and Patrick W. S. Joyce. 2023. "Internationalisation at Home: Developing a Global Change Biology Course Curriculum to Enhance Sustainable Development" Sustainability 15, no. 9: 7509. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097509