Investigations on Entrepreneurship Needs, Challenges, and Models for Countries in Transition to Sustainable Development from Resource-Based Economy—Qatar as a Case

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

2.1. Role of Private Enterprise in Developing and Diversifying the Economy

2.2. Role of Government and Policy in Developing the Private Sector

2.3. Entrepreneurship Needs, Challenges, and Drivers

2.4. Qatar—Status of the Economy, Private Enterprise, and Entrepreneurship

2.5. Norway—A Successful Example of a Country in Transition from a Resource-Based to a Knowledge-Based Economy

- Establish a national governmental company to determine the state’s commercial interests, take control of all the decisions related to the oil industry, and give priority to the nation’s energy supply.

- Focus on creating new opportunities using oil-based investments and engage the other national industries in various oil operations.

- Protect the environment and prevent natural gas burning.

- Set the balance between national and international goals of oil production and enhance Norwegian activities at the international level and their role in the oil economy of the world.

- Collect and audit the oil revenue with accuracy and honesty in order to protect the public interest.

- Undertake comprehensive development planning while considering economic and social sectors to use some of the oil revenue to create new industries and develop sustainable projects.

- Establish a fund for development planning.

- Establish a fund to finance and protect the national economy from oil market variations.

- Developed human capital stemming from the education system and the importation of know-how.

- Strong policies and decision-making platform to regulate businesses, create a stable environment, and control the oil revenue and use it to diversify.

- Highly homogenous culture and high quality of life.

- Largest sovereign wealth fund.

- What is the status of entrepreneurship, and what are the relevant challenges, underlying issues, and barriers in resource-dependent economies such as Qatar?

- What are the critical improvements that could be made to improve entrepreneurship in Qatar as a resource-based economy?

- What alternative, practical, and suitable entrepreneurship frameworks, models, and mechanisms are available for a resource-based economy such as Qatar?

3. Methodology

3.1. Exploratory Research Approach

- The role of economic diversification in building a robust and sustainable economy;

- The current barriers and constraints to entrepreneurship in Qatar;

- The key improvements and opportunities to develop entrepreneurship in Qatar;

- A tailored entrepreneurship framework for Qatar based on these various factors.

3.2. Qualitative Approach

- Successful entrepreneurs;

- Unsuccessful entrepreneurs;

- Entrepreneurs to be;

- Representatives of industry and business;

- Policymakers and government agencies;

- Staff members of entrepreneurship education and training programs and institutes;

- Staff members of entrepreneurship support and promotion programs and agencies;

- Academics (faculty and students).

Description of Interview Preparation, Planning, and Conduct

4. Results Analysis and Discussion

4.1. Current Status

4.2. Interview Results and Findings

4.2.1. Government-Related Challenges and Needs

4.2.2. Industry- and Business-Related Challenges

4.2.3. Supporting Agency Challenges

4.2.4. Social Challenges

4.3. Recommendations

4.3.1. Recommendations for Government

4.3.2. Recommendations for Supporting Agencies

4.3.3. Recommendations for Entrepreneurs

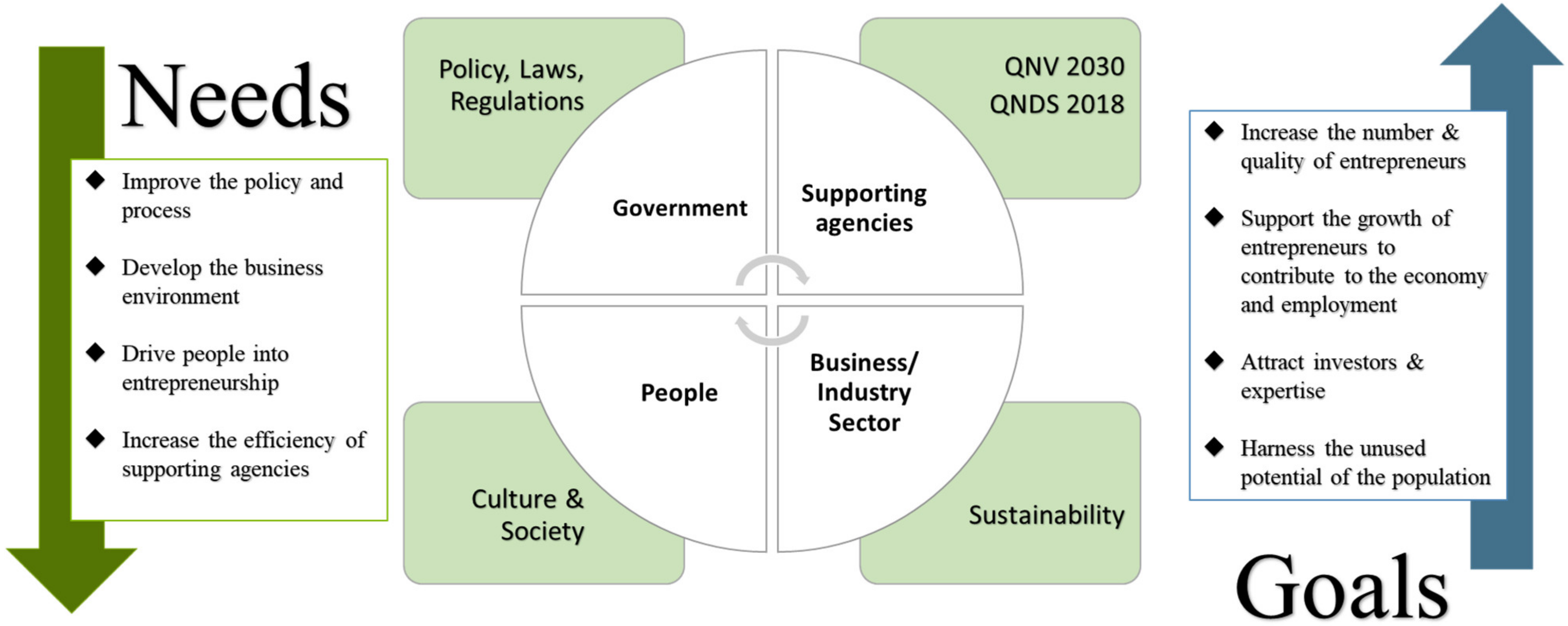

4.4. A preliminary Framework for the Qatar Entrepreneurship Model

4.5. Ent-Q: Special Free Zone for Entrepreneurs

4.6. Ryadah: Digital Entrepreneurship Platform to Facilitate, Grow, and Connect

- Online completion and follow-up of government-related processes (registrations, renewals, visas, tax cards).

- Payment of company bills (Kahramaa, Ooredoo, salaries, fees, taxes, rents).

- An e-check system for payments and a quick legal follow-up system in case of non-payment.

- Bank services integration to ease and facilitate loan requests, changes in monetary authorities, and transfer of salaries.

- Notifications, reminders, and alerts for deadlines, expiry dates of legal documents, new tenders, and payments.

- Business-related information and data repository (size of market, new companies, and average salaries).

- Business-related services (transferring sponsorship, exit permits, and request service).

- Agency-related services (courses, funding, accounting, investor relations, and events). All supporting agencies will be available through a single interface. Entrepreneurs should be more focused on service availability and details rather than on which agency provides the service.

- Tendering interface to apply and participate in tenders. The tenders can also be tracked and audited by the government to ensure support for local startups.

- Tutorials, FAQs, and online support.

4.7. Expected Economic and Social Impacts and Benefits from Ent-Q and Ryadah

5. Conclusions and Limitations

- Complicated and unclear policies and procedures;

- A slow legal system;

- Access to business information;

- High rents;

- Shortage of available expertise;

- Absence of full mentoring;

- Need for contracting opportunities;

- Lack of training;

- Insufficient funding and/or difficulty in accessing risk-based funds.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Demographics:

- Age:

- Education level:

- Gender:

- Employment status:

- Marital status:

- Children:

- 2.

- How many businesses have you tried to establish? How many of them succeeded/failed? Which industry?

- From where did you get your entrepreneurship idea?

- What was your main driver to start those businesses? (Is it need-based? Or opportunity-based?)

- Are you a high-risk, high-reward person? Or do you prefer low-risk, low-reward? Did that change with time?

- Do you have a plan B in case it doesn’t go the way you planned? What does it involve?

- 3.

- Would you start a new additional business?

- Are you willing to leave your own work to pursue full-time entrepreneurship?

- Do you think the business provides enough income that allows you to leave your work and focus on your business?

- If yes, did you leave? And why? If no, would you leave if you make enough?

- Would you stop your entrepreneurial activity for a salary-based job? Why?

- 4.

- Is there anyone in your family who has ever tried to establish her/his own business? Successful or failed?

- Do you think having a close family member who is in business can contribute to your success/driver for entrepreneurship?

- Has this family member helped you in starting your business? If yes, in what way?

- 5.

- Did you/they know about the centers, programs, initiatives that help starting business? Can you name a few?

- From where did you hear about these centers, programs, and initiatives?

- Have you/they used any of those centers’ help, and why?

- In your opinion, do you think those centers are successful in providing support to entrepreneurs?

- What would you recommend to them to be more successful?

- Have you had any issues while dealing with them?

- From where did you get your business skill and did you get any entrepreneurship education?

- From where was the initial capital/funding received? How did you/they raise this funding/capital?

- Would you/they prefer getting a loan with interest from a bank or an investment under risk-sharing methods or any other method that you would recommend?

- 6.

- In your entrepreneurship journey, what challenges have you faced?

- Do you think that those challenges are still present or have things changed?

- Were those challenges personal or system-wise? How?

- Were those challenges in the system on the policy (government/agencies) side? Or the market side?

- How did you/they overcome these challenges?

- If not, how do you think those challenges can be solved?

- 7.

- In your opinion, what are the success factors for entrepreneurship in Qatar?

- What are failing factors?

- What would you recommend to other people who want to pursue entrepreneurship?

- What would you recommend to the government to facilitate/promote/support entrepreneurship?

- What would you recommend to the agencies/centers/universities to facilitate/promote/support entrepreneurship?

- What would you say are the top three skills needed to be a successful entrepreneur?

- What key activities would you recommend entrepreneurs to invest their time in?

- 8.

- Other thoughts and recommendations?

- Do you have a business? (If yes, continue, if not, use the other set of the questions.)

- Demographics:

- Age:

- Education level:

- Gender:

- Employment status:

- Marital status:

- Children:

- Is there anyone in your family who has ever tried to establish her/his own business?

- What was/is it about?

- Successful or failed?

- Do you think having a close family member who is in business can be a driver for entrepreneurship?

- Did you think before to try to establish your own business?

- Why did you? Or why did you not?

- What will drive you to establish your business?

- Do you think the process to start the business is clear? Do you think you could get enough support if you tried?

- Are you a high-risk, high-reward person? Or do you prefer low-risk, low-reward? Did that change with time?

- In your opinion, what are the top three skills needed to be a successful entrepreneur?

- Do you have a financial inspiration? What is it?

- Did you/they know about the centers, programs, initiatives that help starting business? Can you name a few?

- From where did you hear about these centers, programs, and initiatives?

- Have you/they used any of those centers’ help, and why?

- In your opinion, do you think those centers are successful in providing support to entrepreneurs? What would you recommend to them to be more successful?

- Have you had any issues while dealing with them?

- Did you get any form of entrepreneurship education? Where?

- Do you think entrepreneurship education can help you understand more about the topic and in the end drive you to start your business?

- Do you think entrepreneurship is important? Why? What aspects are important for you?

- Would recommend people to start a business?

- What would you recommend to other people who want to start their business?

- In your opinion, what are the main challenges to entrepreneurship in Qatar?

- What do you recommend to do to overcome them?

- In your opinion, what are the success factors for entrepreneurship in Qatar?

- What would you recommend to the government to facilitate/promote/support entrepreneurship?

- What would you recommend to the agencies/centers/universities to facilitate/promote/support entrepreneurship?

- Other thoughts and recommendations?

- Why do you think entrepreneurship is important? What aspects are more important for you?

- What challenges has your organization faced when trying to start its business/program (supporting entrepreneurs)?

- Do you think that those challenges are still present?

- How did you overcome these challenges?

- What is the main driver for entrepreneurship in Qatar?

- What are the main challenges to entrepreneurship in Qatar?

- What are the success factors to entrepreneurship in Qatar?

- What kind of programs, incentive mechanisms, trainings do you offer?

- How many people have you helped establishing their business thus far?

- What are the lines of businesses usually about?

- Majority successful or failed?

- What is the ratio/criteria of your acceptance to support? What is the biggest reason for rejections?

- How do you judge entrepreneurs’ ideas?

- Are they judged by a committee/judges who are entrepreneurs themselves?

- Are many of your organization members also entrepreneurs?

- If yes, why do you think that is? Is it because they got to know the environment?

- If not, do you think this might affect acceptance criteria or the support entrepreneurs get?

- Have you had any greatly successful stories? What was unique about them?

- What do you think about the state of entrepreneurship in Qatar?

- Do you think entrepreneurship in Qatar has developed in the past few years? What is the main reason?

- Do you think Qatar will be able to diversify with the current outlook for entrepreneurship?

- Where do you obtain your funding?

- What kind of publicity do you use to reach entrepreneurs? Newspapers/social media platforms/emails?

- What do you think of the business environment and policies in Qatar?

- What do you recommend to make it better?

- Do you do anything to protect entrepreneurs and their ideas?

- Do you have a feedback channel from entrepreneurs?

- What would you recommend to other people who want to start their business?

- Other thoughts and recommendations?

- Why do you think entrepreneurship is important? What aspects are more important for you?

- In what ways do you think entrepreneurs can play a significant role in economic diversification?

- What do you think is the main driver for entrepreneurs in Qatar?

- What challenges do you see for entrepreneurs in Qatar?

- From your perspective, what are the policies that support entrepreneurs the most?

- From your perspective, what are the policies that hinder entrepreneurs the most?

- How do you think these challenges can be overcome?

- Do you have existing policies/programs to promote entrepreneurship?

- Some new starting businesses feel that they are taken advantage of since they are new to the market. How do you assure them they won’t be taken advantage of, and what do you think should be done to not have such issues?

- Do you have any feedback channels from entrepreneurs? Are they aware of it?

- What do you do to protect entrepreneurs and their ideas?

- What are your next steps to promote entrepreneurship?

- Do you have plans to instate policies/programs to promote entrepreneurship?

- Do some of the people who instate those policies also have entrepreneurship experience?

- If yes, do you think this is because they know the system well?

- If no, do you think they can issue the right policies to entrepreneurs without any experience?

- Other thoughts and recommendations?

References

- Economic Diversification|UNFCCC. Available online: https://unfccc.int/topics/resilience/resources/economic-diversification (accessed on 9 July 2019).

- Hvidt, M. Economic diversification in GCC countries: Past record and future trends. In Kuwait Programme on Development, Governance and Globalisation in the Gulf States; LSE Research Online: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Grey, M. A Theory of “Late Rentierism” in the Arab States of the Gulf Arab States of the Gulf; Center for International and Regional Studies: Doha, Qatar, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gelb, A. Economic Diversification in Resource Rich Countries. In Natural Resources, Finance, and Development: Confronting Old and New Challenges; Center for Global Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Varas, M.E. Economic Diversification: The Case of Chile; Revenue Watch Institute: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-Cendrero, J.M.; Wirth, E. Is the Norwegian model exportable to combat Dutch disease? Resour. Policy 2016, 48, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates Ulrichsen, K. Economic Diversification in Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC); Center for the Middle East, Center for Energy Studies: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Emm, O. Entrepreneurship and Economic Growth: Does Entrepreneurship Bolster Economic Expansion in Africa? J. Soc. 2017, 6, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Statistics Portal. Apple: Annual Revenue 2018|Statista, Statista. 2018. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/265125/total-net-sales-of-apple-since-2004/ (accessed on 10 July 2019).

- Amazon Revenue 2006–2019|AMZN|MacroTrends, Macrotrends LLC. 2019. Available online: https://www.macrotrends.net/stocks/charts/AMZN/amazon/revenue (accessed on 10 July 2019).

- If, Gas Exporting Countries Forum (GECF): Cartel Lite? Background on the GECF, 2018. Available online: www.crs.gov%7C7-5700 (accessed on 9 July 2019).

- Qatar to Leave OPEC and Set Own Oil and Gas Output|CBC News. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/business/qatar-opec-withdrawal-1.4930013 (accessed on 9 July 2019).

- Qatar GDP|2019|Data|Chart|Calendar|Forecast|News. Available online: https://tradingeconomics.com/qatar/gdp (accessed on 10 July 2019).

- Richest Country in the World|Fortune. Available online: https://fortune.com/2017/11/17/richest-country-in-the-world/ (accessed on 10 July 2019).

- A. 2022, Science, Technology and Innovation for Achieving the SDGs: Guidelines for Policy Formulation Innovation for the SDGs and UNIDO WORK STREAM 6: UN Capacity-Building Programme on Technology Facilitation for SDGs In Partnership with the Republic of Korea, (n.d.). Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/sites/default/files/2022-06/ONLINE_STI_SGDs_GUIDELINES_EN_v3_0.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2023).

- Davies, R.; Callan, M. The Role of the Private Sector in Promoting Economic Growth and Reducing Poverty in the Indo-Pacific Region; Development Policy Centre, Crawford School of Public Policy, The Australian National University: Canberra, Australia, 2015; pp. 1–74. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M. The Role of the Private Sector in Generating New Investments, Employment and Financing for Development. 2018, pp. 1–7. Available online: http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/video/2017/04/14/what-are-poverty-lines (accessed on 19 August 2019).

- Concord, on the Role of the Private Sector in Development s 10-Point Roadmap for Europe, 2017. Available online: www.concordeurope.org (accessed on 19 August 2019).

- S+glitz, J.E. Namibia, Role of Government and the Private Sector in a Development State, 2016. Available online: https://www8.gsb.columbia.edu/faculty/jstiglitz/sites/jstiglitz/files/May%2011%20Namibia_Role_of_Government.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2019).

- KEARNEY. Not All SMEs Are Created Equal–Article–Colombia–Kearney. Available online: https://www.co.kearney.com/public-sector/article/-/insights/not-all-smes-are-created-equal (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- Murtinu, S. The government whispering to entrepreneurs: Public venture capital, policy shifts, and firm productivity. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2021, 15, 279–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akosua, M.; Hoedoafia, M.A. Munich Personal RePEc Archive Private Sector Development in Ghana: An Overview Private Sector Development in Ghana: An Overview. 2019. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/96732/ (accessed on 10 March 2020).

- Weber, C.; Fasse, A.; Haugh, H.M.; Grote, U. Varieties of Necessity Entrepreneurship–New Insights from Sub Saharan Africa. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2022, 2022, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairlie, R.W.; Fossen, F.M. Opportunity versus Necessity Entrepreneurship: Two Components of Business Creation. SSRN Electron. J. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US National Women’s Business Council. Necessity as a Driver of Women’s Entrepreneurship, 2017. Available online: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/2158/752483f0d28d28fd175ac342227ebdb74b0b.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2019).

- Elifneh, Y.W. What Triggers Entrepreneurship? The Necessity/Opportunity dichotomy: A Retrospection. J. Poverty Invest. Dev. 2015, 15, 22–28. Available online: www.iiste.org (accessed on 26 August 2019).

- Brünjes, J.; Diez, J.R.; Marburg Geography. Opportunity Entrepreneurs-Potential Drivers of Non-Farm Growth in Rural Vietnam? Working Papers on Innovation and Space. Available online: https://wpis.files.wordpress.com/2013/08/wp01_121.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2019).

- Dumitru, I. Drivers of Entrepreneurial Intentions in Romania. Rom. J. Econ. Forecast. 2018, 21, 157–166. Available online: www.gemconsortium.org (accessed on 26 August 2019).

- Gancarczyk, M.; Ujwary-Gil, A. Exploring the Link Between Entrepreneurial Capabilities, Cognition, and Behaviors; Cognitione: Nowy Targ, Poland, 2021; Volume 17, Available online: www.jemi.edu.pl (accessed on 25 February 2023).

- Kwasi Mensah, E.; Adu Asamoah, L.; Jafari-Sadeghi, V. Entrepreneurial opportunity decisions under uncertainty: Recognizing the complementing role of personality traits and cognitive skills. J. Entrep. Manag. Innov. 2021, 17, 25–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, N.F., Jr.; Carsrud, A.L. Entrepreneurial intentions: Applying the theory of planned behaviour. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 1993, 5, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, N.F., Jr. The Cognitive Psychology of Entrepreneurship. In Handbook of Entrepreneurship Research; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraiger, K.; Ford, J.K.; Salas, E. Application of Cognitive, Skill-Based, and Affective Theories of Learning Outcomes to New Methods of Training Evaluation. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 78, 311–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murnieks, C.Y.; Mosakowski, E.M. Who Am I? Looking Inside the ‘Entrepreneurial Identity’. Available online: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1064901 (accessed on 3 June 2020).

- Van Ness, R.K.; Seifert, C.F.; Marler, J.H.; Wales, W.J.; Hughes, M.E. Proactive Entrepreneurs: Who Are They and How Are They Different? J. Entrep. 2020, 29, 148–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Mattingly, E.S.; Kushev, T.N.; Ahuja, M.K.; Manikas, A.S. Persistence Decisions: It’s Not Just About the Money. J. Entrep. 2019, 28, 121–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, D.K.; Wiklund, J.; Cotton, R.D. Success, Failure, and Entrepreneurial Reentry: An Experimental Assessment of the Veracity of Self-Efficacy and Prospect Theory. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2017, 41, 19–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, R.; Shankar, R.K. Three Mindsets of Entrepreneurial Leaders. J. Entrep. 2020, 29, 7–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.E.; Ucbasaran, D.; Cacciotti, G.; Williams, T.A. Integrating Psychological Resilience, Stress, and Coping in Entrepreneurship: A Critical Review and Research Agenda. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2022, 46, 497–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalkan, M.; Kaygusuz, C. The Psychology of Entrepreneurship. In Entrepreneurship–Born, Made and Educated; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2012; p. 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlinska, I. Fundamental View of the Outcomes of Entrepreneurship Education. SSRN Electron. J. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala, J.C.; Manzano, G. The resilience of the entrepreneur. Influence on the success of the business. A longitudinal analysis. J. Econ. Psychol. 2014, 42, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GDP per Capita (Current US$)–Qatar|Data. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD?locations=QA (accessed on 18 February 2023).

- Qatar Monthly Statistics, 2020. Available online: https://www.psa.gov.qa/en/statistics/Statistical%20Releases/General/QMS/QMS_PSA_75_April_2020.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2020).

- Qatar GDP Growth Rate|2004-2019 Data|2020-2022 Forecast|Calendar|Historical. Available online: https://tradingeconomics.com/qatar/gdp-growth (accessed on 10 March 2020).

- Jolo, A.M.; Ari, I.; Koç, M. Driving Factors of Economic Diversification in Resource-Rich Countries via Panel Data Evidence. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, A.; Tok, E.; Koc, M.; Mezher, T.; Tsai, I.-T. Economic Diversification Potential in the Rentier States towards a Sustainable Development: A Theoretical Model. Sustainability 2019, 11, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ari, I.; Akkas, E.; Asutay, M.; Koç, M. Public and private investment in the hydrocarbon-based rentier economies: A case study for the GCC countries. Resour. Policy 2019, 62, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekih Zguir, M.; Dubis, S.; Koç, M. Embedding Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) and SDGs values in curriculum: A comparative review on Qatar, Singapore and New Zealand. J. Clean Prod. 2021, 319, 128534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Thani, W.A.; Ari, I.; Koç, M. Education as a Critical Factor of Sustainability: Case Study in Qatar from the Teachers’ Development Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kuwari, M.M.; Al-Fagih, L.; Koç, M. Asking the Right Questions for Sustainable Development Goals: Performance Assessment Approaches for the Qatar Education System. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachef, T.; bin Jantan, M.; Boularas, A. Fuzzy Modelling for Qatar Knowledge-Based Economy and Its Characteristics. Mod. Econ. 2014, 5, 224–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- The World Bank Group. Ease of Doing Business Score and Ease of Doing Business Ranking. 2018, pp. 126–132. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/32436/9781464814402_Ch06.pdf?sequence=23&isAllowed=y (accessed on 10 March 2020).

- Qatar—Unemployment Rate 1999–2019|Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/808890/unemployment-rate-in-qatar/ (accessed on 3 June 2020).

- Product and Services. Available online: https://www.qdb.qa/en/products-services (accessed on 7 April 2020).

- Vision & Mission–Qatar Science and Technology Park. Available online: https://qstp.org.qa/vision-mission/ (accessed on 8 April 2020).

- Widen, E. QBIC Is Creating the Next Generation of Qatari Business Leaders. Entrepreneur Middle East, 1 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Founders & Partners—Qatar Business Incubation Center. Available online: http://www.qbic.qa/en/about/founders-partners/ (accessed on 7 April 2020).

- INJAZ Qatar. Available online: https://www.injaz-qatar.org/en (accessed on 7 April 2020).

- Bedaya–Meet Young People, Learn New Skills. Become a Volunteer, Have Fun and Learn. Available online: http://www.bedaya.qa/en/#who-we-are (accessed on 7 April 2020).

- نماء–الرسالة والرؤية (Vision and Mission). Available online: https://www.nama.org.qa/about-nama-ar/vision-mission-ar (accessed on 7 April 2020).

- Center for Entrepreneurship|Qatar University. Available online: http://www.qu.edu.qa/business/entrepreneurship-center (accessed on 7 April 2020).

- Young Entrepreneurs–Carnegie Mellon University in Qatar: Carnegie Mellon University in Qatar. Available online: https://www.qatar.cmu.edu/future-students/workshops-events/young-entrepreneurs/ (accessed on 7 April 2020).

- Entrepreneurship. Available online: https://www.cna-qatar.com/Training/Pages/Entrepreneurship.aspx (accessed on 7 April 2020).

- Dewe Rogerson Ramiz Al-Turk, C. Sheikh Faisal Center for Entrepreneurship. Available online: www.alfaisalholding.com (accessed on 7 April 2020).

- Arab Innovation Academy|Qatar 2020. Available online: https://www.inacademy.eu/qatar/ (accessed on 7 April 2020).

- QDB. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor; QDB: Doha, Qatar, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- QDB. Small and Medium Enterprise (SME) Toolkit, 2017. Available online: https://www.qdb.qa/en/Documents/QDB%20SME%20Toolkit%20-%2025%209%202017.pdf (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- Ola, G. The Economic History of Norway, EH.Net. 2008. Available online: https://eh.net/encyclopedia/the-economic-history-of-norway/ (accessed on 13 April 2023).

- Norway: A History from the Vikings to Our Own Times. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40919935?read-now=1&seq=3#metadata_info_tab_contents (accessed on 13 April 2023).

- Larsen, E.R. The Norwegian Economy 1900–2000: From Rags to Riches a Brief History of Economic Policymaking in Norway 1. Available online: https://www.uio.no/studier/emner/hf/iln/NORINT0500/h08/undervisningsmateriale/The_Norwegian_Economy_1900-2000.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2023).

- Sejersted, F. The development of economic history in Norway. Scand. Econ. Hist. Rev. 2011, 36, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norway–Economic Conditions|Britannica.com. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/place/Norway/World-War-II (accessed on 13 April 2023).

- Ove, K.; Wallerstein, M. Special Report the Scandinavian Model and Economic Development. Available online: https://www.frisch.uio.no/publikasjoner/pdf/TheScandinavianModelandEconomicDevelopment.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2023).

- Dalgaard, B.R.; Supphellen, M. Entrepreneurship in Norway’s economic and religious nineteenth-century transformation. Scand. Econ. Hist. Rev. 2011, 59, 48–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norsk Olje & Gass, Norway’s Petroleum History, Norskoljeoggass. No. 2010. Available online: https://www.norskpetroleum.no/en/framework/norways-petroleum-history/ (accessed on 25 September 2019).

- Mohammad Alameen, Y.M. The Norwegian Oil Experience of Economic Diversification: A Comparative Study with Gulf Oil. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2016, 8, 94–101. [Google Scholar]

- SWF Institute, Top 93 Largest Sovereign Wealth Fund Rankings by Total Assets, Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute. 2020. Available online: https://www.swfinstitute.org/fund-rankings/sovereign-wealth-fund (accessed on 13 April 2023).

- 20 Best Education System in the World–Edsys. Available online: https://www.edsys.in/best-education-system-in-the-world/ (accessed on 13 April 2023).

- Norway Calling All U.S and U.K. Tech Hipsters. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/lawrencewintermeyer/2018/01/19/norway-calling-all-us-and-uk-tech-hipsters/#7a361b7758fb (accessed on 13 April 2023).

- Norway, Entrepreneurial Paradise. Available online: http://blogs.reuters.com/felix-salmon/2011/01/20/norway-entrepreneurial-paradise/ (accessed on 13 April 2023).

- Reuters Graphics, Reuters Graphics, 2019. Available online: https://graphics.reuters.com/ (accessed on 13 April 2023).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, C.; Ziebland, S.; Mays, N. Qualitative research in health care: Analysing qualitative data. BMJ Br. Med. J. 2000, 320, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teka, B.M. Determinants of the sustainability and growth of micro and small enterprises (MSEs) in Ethiopia: Literature review. J. Innov. Entrep. 2022, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endris, E.; Kassegn, A. The role of micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) to the sustainable development of sub-Saharan Africa and its challenges: A systematic review of evidence from Ethiopia. J. Innov. Entrep. 2022, 11, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wildpixel, GEM 2020/2021. 2021. Available online: http://www.witchwoodhouse.com (accessed on 17 November 2021).

- Tok, E.; Koç, M.; D’Alessandro, C. Entrepreneurship in a transformative and resource-rich state: The case of Qatar. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2021, 8, 100708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Business Enabling Environment. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/business-enabling-environment (accessed on 3 September 2022).

- Al-Qahtani, M.; Zguir, M.F.; Ari, I.; Koç, M. Female Entrepreneurship for Sustainable Economy and Development—Challenges, Drivers, and Suggested Policies for Resource-Rich Countries. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qahtani, M.; Fekih Zguir, M.; Al-Fagih, L.; Koç, M. Women Entrepreneurship for Sustainability: Investigations on Status, Challenges, Drivers, and Potentials in Qatar. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mulla, A.; Ari, I.; Koç, M. Sustainable financing for entrepreneurs: Case study in designing a crowdfunding platform tailored for Qatar. Digit. Bus. 2022, 2, 100032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndofirepi, T.M. Entrepreneurship goal and implementation intentions formation: The role of higher education institutions and contexts. J. Innov. Entrep. 2022, 11, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amofah, K.; Saladrigues, R. Impact of attitude towards entrepreneurship education and role models on entrepreneurial intention. J. Innov. Entrep. 2022, 11, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, B.H.; Ari, I.; Al-Sada, M.b.S.; Koç, M. Strategizing Human Development for a Country in Transition from a Resource-Based to a Knowledge-Based Economy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, B.H.; Disli, M.; Al-Sada, M.b.S.; Koç, M. Investigation on Human Development Needs, Challenges, and Drivers for Transition to Sustainable Development: The Case of Qatar. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrell, A.; Hsu, J. Exploring and Preparing for Successful Cross-continental Knowledge and Technology Transfer: A Case Study on International Open Innovation. J. Entrep. Innov. Emerg. Econ. 2019, 5, 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrell, A.; Paalzow, A.; Baltins, E.; Storgårds, J.; Purmalis, K.; Berzina, K.; Mara Irbe, M.; Ozolins, M. Cross-border Entrepreneurial Education, Development and Knowledge and Technology Transfer: Experiences with the Cambridge–Riga Venture Camp Programme—A Reflective Report. J. Entrep. Innov. Emerg. Econ. 2021, 7, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madbouly, A.; al Khayyal, H.; Mourssi, A.; al Wakeel, W. Determinants of GCC Women Entrepreneurs Performance: Are they Different from Men? J. Asian Bus. Strategy 2021, 11, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlovski, I. Drivers of Success to Effective Entrepreneurship: A Comparison Drivers of Success to Effective Entrepreneurship: A Comparison of Immigrant and Native-born Perceptions of Immigrant and Native-born Perceptions; Georgia State University: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quatraro, F.; Vivarelli, M. Drivers of Entrepreneurship and Post-Entry Performance of Newborn Firms in Developing Countries. In World Bank Research Observer; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Alfonso, J.; Pavón, T. Entrepreneurship and the Business Plan Title: Kyne Solutions-Entrepreneurship and the Business Plan.

- Osadolor, V.; Agbaeze, E.K.; Isichei, E.E.; Olabosinde, S.T. Entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial intention: The mediating role of the need for independence. J. Entrep. Manag. Innov. 2021, 17, 91–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crudu, R. The role of innovative entrepreneurship in the economic development of EU member countries. J. Entrep. Manag. Innov. On. 2019, 15, 35–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, M.K.; Gautam, M.K.; Scholar, R.; Singh, S.K. Entrepreneurship Education View Project Entrepreneurship Education: Concept, Characteristics and Implications for Teacher Education. 2015. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/319057540 (accessed on 13 April 2023).

- Mani, M. Entrepreneurship Education: A Students’ Perspective, in: Business Education and Ethics: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2017; pp. 526–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miço, H.; Cungu, J. Entrepreneurship Education, a Challenging Learning Process towards Entrepreneurial Competence in Education. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valerio, A.; Parton, B.; Robb, A. Entrepreneurship Education and Training Programs around the World Dimensions for Success Human Development; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Florek-Paszkowska, A.; Ujwary-Gil, A.; Godlewska-Dzioboń, B. Business innovation and critical success factors in the era of digital transformation and turbulent times. J. Entrep. Manag. Innov. 2021, 17, 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.U. How funding matters: Reinitiating of New Product Development and the moderating effect of extramural R&D. J. Entrep. Manag. Innov. 2022, 18, 185–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bel Hadj Miled, K.; Younsi, M.; Landolsi, M. Does microfinance program innovation reduce income inequality? Cross-country and panel data analysis. J. Innov. Entrep. 2022, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruthi, S.; Mitra, J. Special Issue on ‘Migrant and Transnational Entrepreneurs: International Entrepreneurship and Emerging Economies’. J. Entrep. Innov. Emerg. Econ. 2020, 6, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntshadi Ganamotse, G.; Samuelsson, M.; Abankwah, M.; Anthony, T.; Mphela, T. The Emerging Properties of Business Accelerators: The Case of Botswana, Namibia and Uganda Global Business Labs. J. Entrep. Innov. Emerg. Econ. 2017, 3, 16–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njoku, K.C.; Cooney, T.M. How Does the Man-Know-Man Network Culture Influence Transnational Entrepreneurship? J. Entrep. Innov. Emerg. Econ. 2020, 6, 163–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A.R.; Jack, S.L.; Dodd, S.D. The role of family members in entrepreneurial networks: Beyond the boundaries of the family firm. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2005, 18, 135–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.psa.gov.qa/en/knowledge/Documents/NDS2Final.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2023).

- Available online: https://www.gco.gov.qa/en/about-qatar/national-vision2030/ (accessed on 13 April 2023).

- Bayat, P.; Daraei, M.; Rahimikia, A. Designing of an open innovation model in science and technology parks. J. Innov. Entrep. 2022, 11, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Cognitive Competencies | Main Theme | Subtheme | Explanation |

| Knowledge | Mental models | Knowledge about how to do things with limited resources. | |

| Declarative knowledge | Knowledge of entrepreneurship, idea generation, opportunities, value creation, technology, marketing, etc. | ||

| Self insights | Self-understanding, evaluation, criticism, and improvement. | ||

| Skills | Marketing skills | Ability to conduct market research, assessment, persuasion, convincing people with your ideas, etc. | |

| Resource skills | Creating a business plan, financial plan, obtaining financing, securing resources. | ||

| Opportunity skills | Recognizing and acting upon business opportunities, product/service/concept development skills. | ||

| Non-Cognitive Competencies | Interpersonal skills | Leadership, motivating and managing the team, resolving conflict. | |

| Learning skills | Active learning and adaptations to new situations and uncertainty. | ||

| Strategic skills | Objectives setting, defining a vision, and developing the strategy. | ||

| Attitude | Entrepreneurial passion | Need for achievement. | |

| Self-efficacy | Belief in own ability to perform. | ||

| Entrepreneurial identity | Role identity and having values. | ||

| Proactiveness | Action-oriented and proactive. | ||

| Uncertainty/ambiguity tolerance | Comfortable with uncertainty. | ||

| Innovativeness | Novel thoughts/actions, visionary, creative. | ||

| Perseverance | Ability to overcome adverse situations. |

| Institute | Program | Objectives and Activities | Started |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qatar Development Bank | Financial services | Improve the economic development cycle by providing entrepreneurs and SMEs with a wide range of financial and advisory products under one roof: | 1997 |

| Advisory services | |||

| Qatar Science & Technology Park | Financial services |

| 2009 |

| Advisory services | |||

| Qatar Business Incubation center | Incubation | Training | 2013 |

| Acceleration | Financing and loans | ||

| Manufacturing | Consultation and services | ||

| Fashion brand creation | Networking | ||

| Injaz Qatar | Entrepreneurship programs | Educating, courses, training, and networking | 2007 |

| Bedaya | Advisory services | Advisory services | 2011 |

| Silatech | Financial services | Financing and loans | 2008 |

| Advisory and training services | Capacity building and training | ||

| Nama | Sama Nama (social entrepreneurship program) |

| 1996 |

| Advisory services | |||

| Qatar University, Center for Entrepreneurship (CFE) | ERADA (training program) |

| 2013 |

| From innovation to commercialization | |||

| Business incubator | |||

| College of North Atlantic, Entrepreneur Center | Al Ruwad |

| 2015 |

| Carnegie Melon | Young Entrepreneurs | Raise awareness and training | N/A |

| Al-Faisal Holding | Sheikh Faisal Center for Entrepreneurship | Connect entrepreneurs and training | 2014 |

| Innovation Academy | Qatar Innovation Academy | Training | N/A |

| Non-Entr. | Entr. | Policymakers | Investors | Support Agencies | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Communicated | 5 | 20 | 9 | 5 | 11 |

| Responded | 5 | 18 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| Response % | 100% | 90% | 44% | 60% | 36% |

| Age | 18–29 | 30–39 | 40–49 | 50+ | |

| 5 | 15 | 8 | 6 | ||

| Type | Non-entrep. | Entrepreneur | Policymaker | Investor | Support agency |

| 5 | 18 | 4 | 3 | 4 | |

| Education level | High school | BS/BA | MS | PhD | |

| 3 | 10 | 16 | 5 | ||

| Marital status | Married | Single | |||

| 28 | 6 | ||||

| Employment | Self-employed | Employed | Both | ||

| 2 | 15 | 17 | |||

| Children | 0 | 1–2 | 3+ | ||

| Ent-Q Benefits | Ent-Q Challenges and Requirements |

|---|---|

| Provide a fertile environment for entrepreneurs in Qatar to flourish with a supportive legal system and a simplified, streamlined process. | Significant support is required from the government and decision-makers. → Agreement from decision-makers. |

| Support entrepreneurs through low rent and tax incentives and provide them the opportunity to focus on expanding their business. | Collaboration is necessary from supporting agencies and ministries. → Support from decision-makers. |

| Create a collaboration so that national companies support the local entrepreneurship environment and entrepreneurs help find tailored solutions to companies’ challenges. | Risk of misuse of services. → Independent audit committee. |

| Requirement of a high budget. → Support from the government. |

| Ryadah Benefits | Ryadah Challenges |

|---|---|

| Automation, clarity, simplicity, and efficiency. | High-level, continuous, and productive collaboration between ministries is needed, which requires consensus, agreement, and support from decision-makers. |

| Tackles most business environment needs from all angles. | Supporting agencies will need to work as a team. → Agreement/support from decision-makers |

| Documentation of transactions and data. | |

| Marketing and easiness of doing business. | Users will need to be accustomed to online services. → Education and time. |

| Easier communication with supporting agencies. | |

| Environmental advantages and time savings. | Security concerns. → Hire world-class cybersecurity experts. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al-Housani, M.I.; Koç, M.; Al-Sada, M.S. Investigations on Entrepreneurship Needs, Challenges, and Models for Countries in Transition to Sustainable Development from Resource-Based Economy—Qatar as a Case. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7537. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097537

Al-Housani MI, Koç M, Al-Sada MS. Investigations on Entrepreneurship Needs, Challenges, and Models for Countries in Transition to Sustainable Development from Resource-Based Economy—Qatar as a Case. Sustainability. 2023; 15(9):7537. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097537

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl-Housani, Mohammad I., Muammer Koç, and Mohammed S. Al-Sada. 2023. "Investigations on Entrepreneurship Needs, Challenges, and Models for Countries in Transition to Sustainable Development from Resource-Based Economy—Qatar as a Case" Sustainability 15, no. 9: 7537. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097537

APA StyleAl-Housani, M. I., Koç, M., & Al-Sada, M. S. (2023). Investigations on Entrepreneurship Needs, Challenges, and Models for Countries in Transition to Sustainable Development from Resource-Based Economy—Qatar as a Case. Sustainability, 15(9), 7537. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097537