Abstract

Collaborative forest management (CFM) is assumed to provide benefits for improving the condition of the forest ecology and the community’s economy. However, its effectiveness is often debated, particularly regarding the involvement of poor and landless farmers in program implementation. In this relation, this study examines a CFM program implementation in Bandung District, West Java, the so-called Pengelolaan Hutan Bersama Masyarakat (PHBM). The study combined qualitative and quantitative approaches in collecting data. GIS analysis and vegetation identification supported this study. The study shows that the PHBM program implementation in the study area provided benefits for improving forest ecological conditions and the livelihood of the farmers. This study also suggests that poor or landless farmers could secure their rights and access to the forest; they became coffee farmers. Despite this, to ensure the sustainability of the program, especially the involvement of the poor and landless farmers, support from the government is very much needed.

1. Introduction

The success of managing natural resources, such as forests, carried out only by the state has been long questioned. The state has often failed to manage natural resources sustainably and equitably [1]. On the contrary, many researchers argue that community group-based natural resource management can sustainably manage natural resources. The success of the community in taking care of these natural resources has encouraged the development of a community-based forest management system (CBFM) or collaborative forest management system (CFM) [2,3,4]. Successful examples of CBFM or CFM are presented in many South American and Asian countries [5,6]. Relatively recent studies show the achievements of CBFM in the REDD program in Tanzania [7], the CFM that can rehabilitate forests in Ethiopia [8] and the CFM which has reduced deforestation in Indonesia [9].

Some authors argued that the CBFM or CFM can provide benefits for forest conservation and livelihoods for the community [10,11], village development, and improvement of the local people’s household economy [12]. By building local capacity and serious government support, CBFM or CFM programs can promote sustainable forest management. It is achievable when the communities depend on forest resources for their livelihoods [13]. Local communities who live close to the resources are more likely than the governments to pay attention to the long-term consequences of resource use because they depend upon the sustainable harvesting of the resource for their livelihoods [14].

Apart from those success stories, several articles criticized the achievements of the CBFM or CFM-based forest management programs. A study revealed the failure of such management system in promoting sustainability goals: efficiency, equity, democratic participation, and poverty alleviation [3]. Although the community forest management program succeeded in improving the ecological condition of forests, it failed to achieve other global indicators—for instance, increasing community welfare [15]. CBFM increased the vulnerability of marginalized groups in society [16]. In Indonesia, a study outside Java shows that the CBFM program did not pay attention to community participation and aspirations [17]. Other researchers mention many facts that indicate the potential of collaborative forest management for the welfare of poor people was weak [18]. Elite groups in their communities co-opted opportunities for poor people to gain access to forest management. The elite mostly controlled the entire resource management processes [19]. Due to several different findings as presented above, a researcher says further research to evaluate and investigate CBFM or CFM programs is necessary to carry out [20].

Regardless of the weaknesses in collaborative forest management, this study assumed that the involvement of communities in the CFM would promote better forest management. Without community involvement in forest management, the success of forest management is doubtful. The forest management program that only aims for the sake of conservation is just in vain. Forest management carried out in collaboration with the community will be able to protect the forest and will be able to provide economic welfare for the local community.

By taking a case from Bandung District, West Java, this study aims to demonstrate the importance of community involvement in forest management as an effort to carry out sustainable forest management by focusing on the process and impact of community involvement in a collaborative forest management program called Pengelolaan Hutan Bersama Masyarakat (PHBM), a kind of collaborative forest management in Java, a second generation of social forestry program in Indonesia [21]. Collaboratively, this program re-involved local communities in forest management and allowed the utilizing of part of the forestlands with the obligation to conserve forest ecosystem and participate in reforesting the critical bare forestlands.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Area

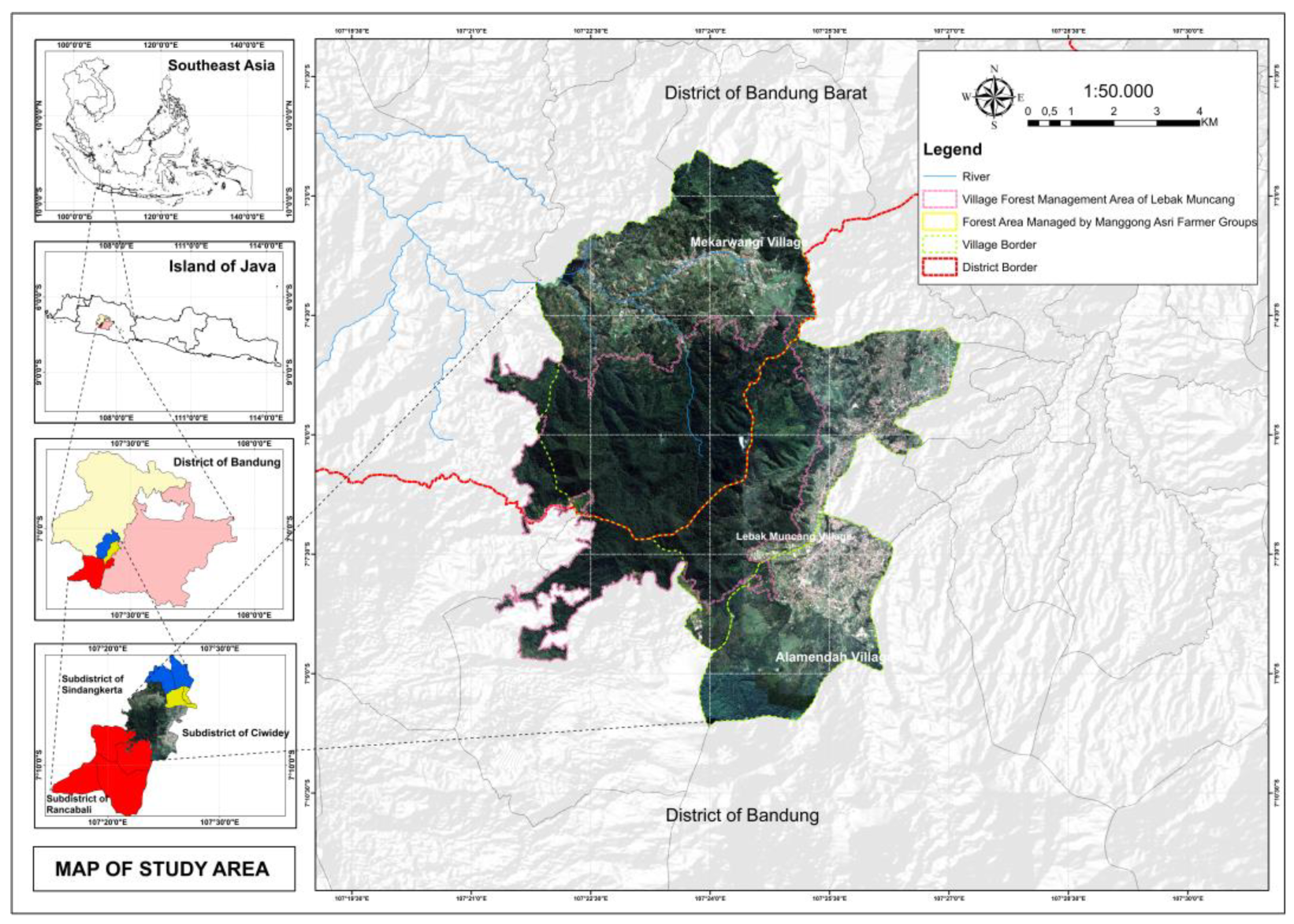

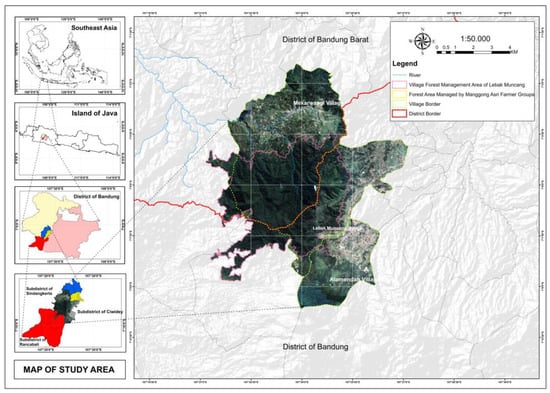

This study was carried out in a forest area at Kesatuan Pemangkuan Hutan/KPH Bandung Selatan (South Bandung Forest Management Unit). The study area is part of the Bandung District (Figure 1), in the upper part of the Citarum watershed, one of several watersheds in Java categorized as the most critical watershed [13].

Figure 1.

Study area.

Intensive research was conducted by studying a Lembaga Masyarakat Desa Hutan/LMDH (a forest village community organization). Formally, even though the LMDH was registered in a village in Bandung District, members of the LMDH were from three villages in three different sub-districts: Lebak Muncang Village-Ciwidey Sub-district and Alam Endah Village-Rancabali Sub-district—both were in Bandung District—and Mekarwangi Village-Sindang Kerta Sub-district in West-Bandung District.

2.2. Data Collection

In this study, the relevant data were collected using a qualitative approach to study the process of community involvement in the PHBM program in the selected research site. The study conducted observations and in-depth interviews with purposively selected informants: the officials of the Forest Management Unit, the village apparatus, the representatives of the LMDH, and the forest farmer groups. The data collected includes the history of forestland encroachment, the development of PHBM policy and collaborative forest management in the study area, and the history of involvement of local community in the PHBM program. The study also interviewed 48 households involved in the PHBM program who lived in a sub-village of Lebak Muncang Village and were members of a farmer group. The data collected in this household survey include socioeconomic status of the household: occupation, land ownership, involvement in the PHBM program, and sources of living. Regarding the in-depth study at the sub-village level, Kampung (sub-village) forms the factual unit of community interaction [22].

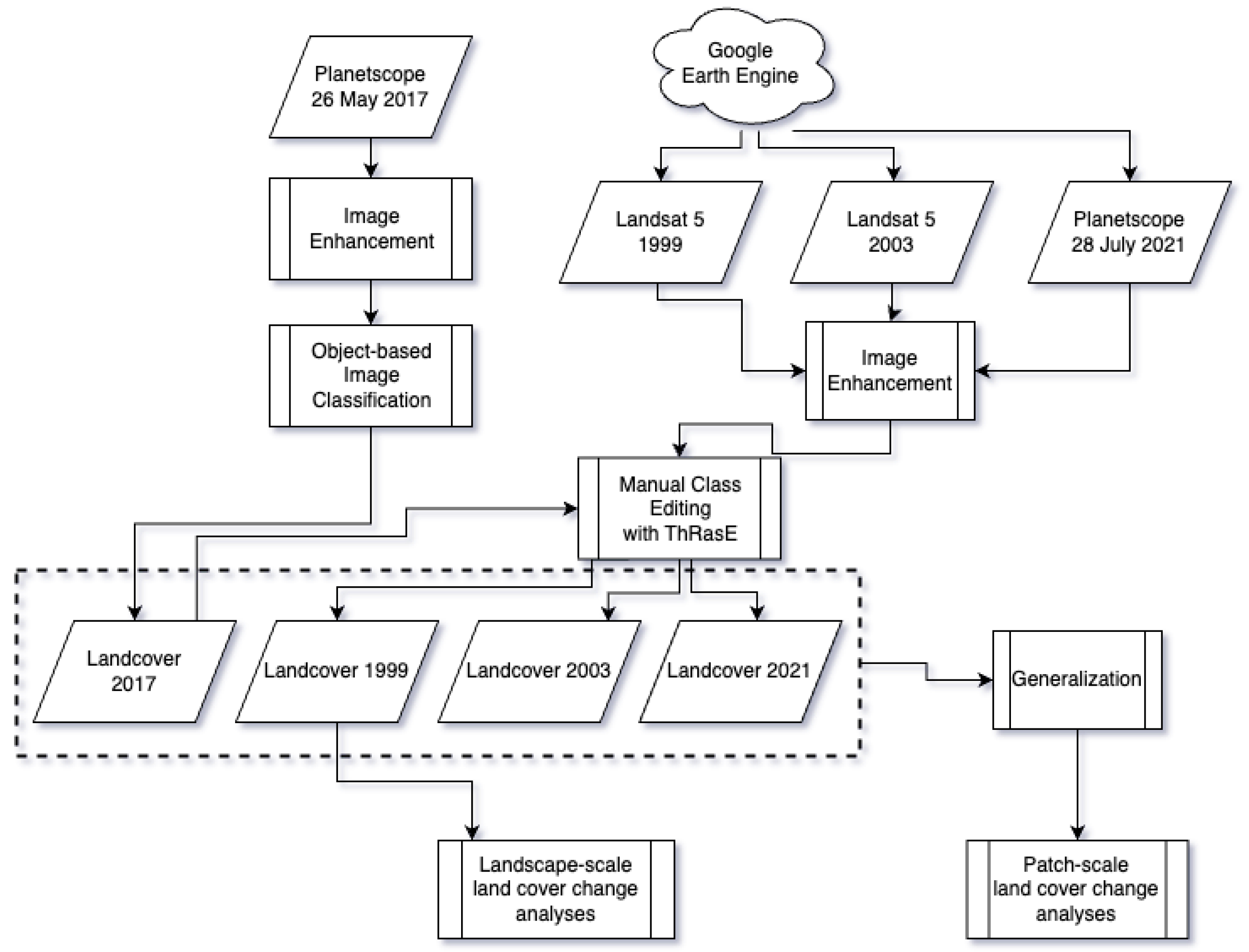

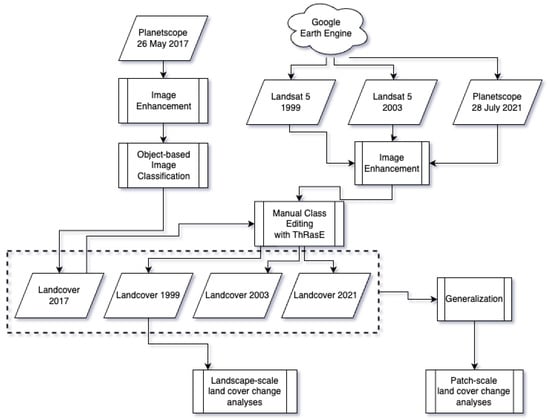

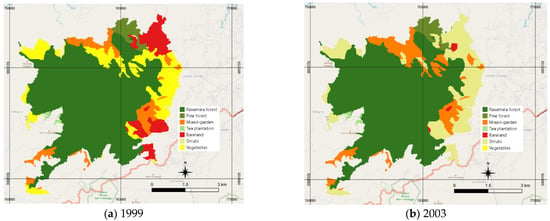

GIS analysis supported the study to see changes in forest cover between the period before and after the PHBM program (1999–2021) by interpreting satellite imagery from Planet Team [23] using the software QGIS and GRASS GIS. The data used were multi-temporal satellite imagery data starting from 1999, 2003, 2017, and 2021. The satellite imagery used for 1999 and 2003 was Landsat 5 TM imagery with a spatial resolution of 30 m. For 2017 and 2021, the images used were Planetscope with a resolution of 3 m. The study utilized the Google Earth Engine to get Landsat 5 TM imagery and the Planet Imagery Education and Research Program License scheme to get Planetscope. The analysis carried out simple pre-processing to enhance all images.

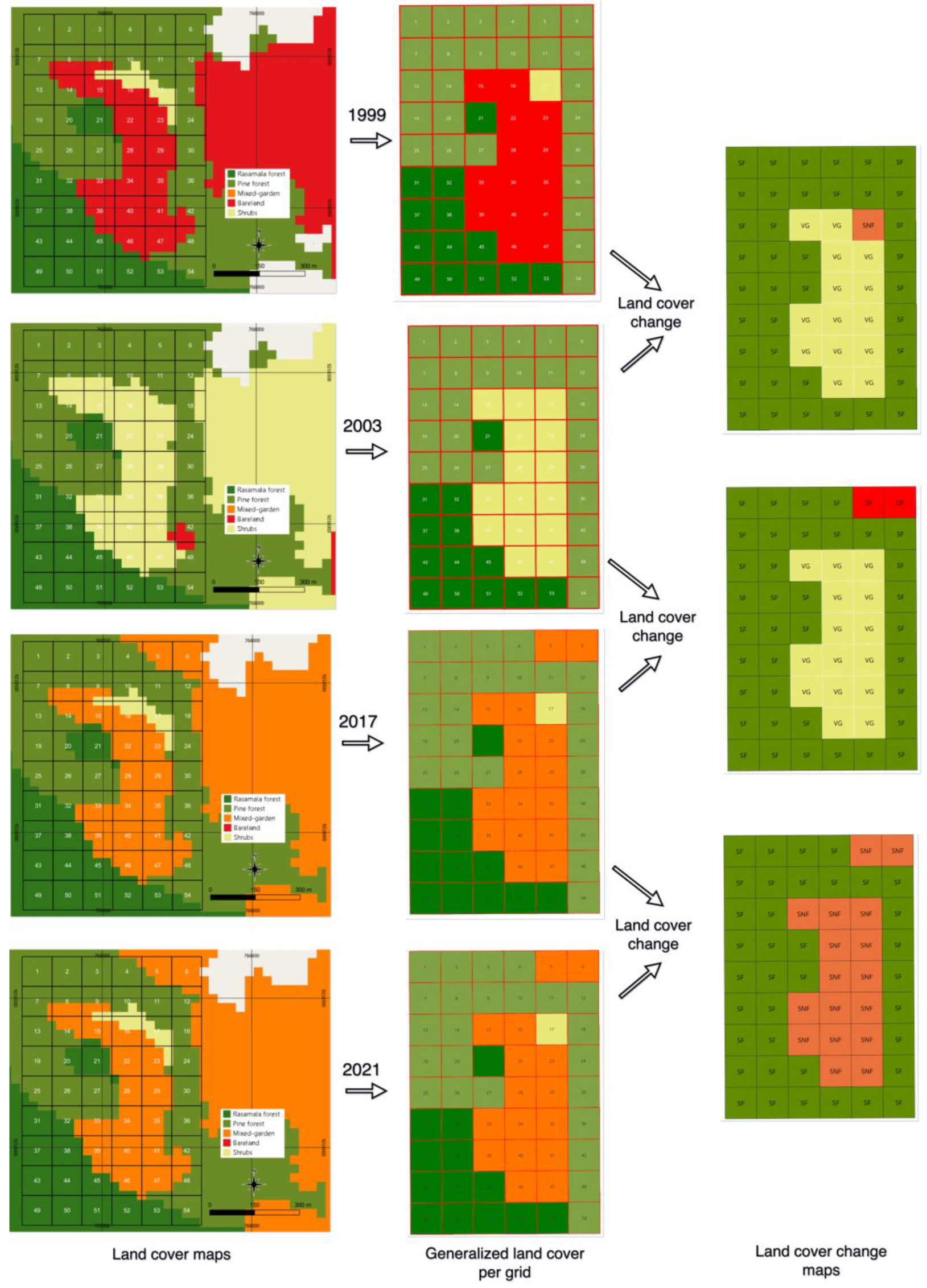

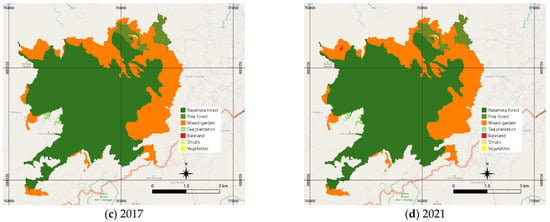

The Planetscope 25 May 2017 image was used as a baseline image for land cover analysis using the Object-Based Image Analysis method. For 1999, 2003, and 2021 land covers, the study performed an overlay imagery analysis of the year associated with the 2017 Landcover (vector). Pixels with different land covers were manually classified using ThRasE (QGIS plugin). The study analyzed landcover change at (1) landscape scale and (2) plot scale. For patch-scale land cover analysis, this study used each year’s generalized land cover map (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Classification methods workflow.

On a landscape scale, the study analyzed a forest area covering 3340.41 hectares to identify changes in forest land use between 1999 and 2021. On a plot scale, purposively, an analysis was also carried out on 54 hectares of forestland managed by a farmer group to identify changes in land cover. The study applied technique to estimate the accuracy of land cover change by filling the matrix with one of the six classes of change, namely: (1) Stable Forest (SF), (2) Deforestation (DEF), (3) Forest Degradation (DEG), (4) Stable Non-Forest (SNF), (5) Forest Gain (FG), and (6) Vegetation Gain (VG) [24]. Forest gain is a class where the land cover in the previous period is non-forest and the following year is forest, both natural forest and plantation forest. Vegetation gain is a class where the land cover in both periods is non-forest, in the next period has better carbon stocks (for example, agroforest from shrubs). The study carried out plot scale analysis in three periods: (1) between 1999–2003 or t1, (2) between 2003 and 2017 or t2, and (3) between 2017 and 2021 or t3. In the period of t1, t2, and t3, the class of land cover change that occurred were (1) Deforestation, (2) Stable Forest, (3) Stable-Non-Forest and (4) Vegetation Gain. The study also applied Univariate Local Moran’s I [25] to conduct a geostatistical analysis to analyze whether or not land cover changes occurred spontaneously.

Identification of forest vegetation also supported the study, especially in 54 hectares of forest areas managed by the interviewed members of a farmer group. The data on vegetation composition in the form of trees, pioneer plants, and cultivated plants were collected using the roaming survey method. The study carried out a roaming survey in an area of 54 hectares of forest area divided into 54 grids.

The study observed the composition of the vegetation using natural transects in the form of footpaths often used by farmers to identify plant species found in forest land managed by the interviewed members of the farmer group. A study reveals that participatory forest management can affect species composition [26]. A visual estimation was used by observing the distribution patterns of plants that made up tree stands, pioneer plants, and cultivated plants to identify vegetation composition on different land cover.

2.3. Collaborative Forest Management and Coffee Cultivation: Research Context

In Java, forest management that involves the community, locally known as Tumpang Sari, has been applied since the colonial era in the 1880s. The forest management allowed people to grow food crops in between rows of teak seeds for a few years. After World War II, the forest management system evolved into a more socially responsive Social Forestry program [27,28,29,30,31]. However, the system did not anticipate the changes in the social condition of the forest villages and appropriately adjusted to the forest management system. These resulted in illegal logging, overgrazing, and increased encroachment, which in turn caused excessive forest degradation [32].

In West Java, particularly in the South Bandung area, the people living around forest area had long been involved in the Tumpang Sari program in forest areas. However, many accused such activity of causing damage to the forest environment. Responding to the severe forest degradation, in the mid-1980s the provincial government of West Java stopped the Tumpang Sari program in the forest area of Bandung District. Instead of recovering, however, forest degradation was even worse. Local people overrode the prohibition. At the same time, the forest managers were also unable to manage the forest properly.

Illegal activities became increasingly symptomatic during the 1997/8 economic crisis. Many people encroached on the forestlands to engage in cultivation. People earned an income that helped them overcome the problems of the crisis. But, as a result, forest destruction was getting worse. Local farmers cut forest trees and cleared the forestlands (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Encroached forestland (nature reserve) in Southern Bandung area in early 2000s.

To prevent further forest destruction, the government firmly stopped all illegal cultivation activities in forest areas in the South of Bandung area in 2000/1. In 2001, Perum Perhutani, the Forest Management of Java, formulated a policy, the so-called Pengelolaan Hutan Bersama Masyarakat (PHBM), a kind of collaborative forest management that applies throughout Java. This policy changed the existing forest management system. For the people in the surrounding forest area, it gave back access to involvement in forest management.

PHBM is a program developed by Perum Perhutani to involve local communities in forest management. The program’s objectives are to provide economic benefits to local communities while preventing encroachment and improving the ecological condition of forest areas. This program is implemented collaboratively between Perum Perhutani and the local community organized in Lembaga Masyarakat Desa Hutan (Forest Village Community Organization) or LMDH.

The PHBM aims to provide direction for forest resource management by combining economic, ecological, and social aspects [33]. PHBM provides access to communities around the forest to manage forests in a participatory manner without changing the status and function of the forest, based on some principles, including a sharing system.

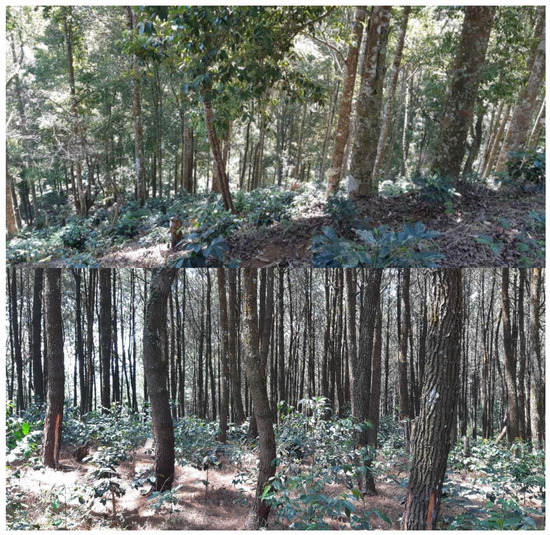

From 2003–4, collaboratively, local communities were allowed and started to utilize part of the forestlands, but they were obliged to maintain the forest trees and participate in the reforestation of the critical forestlands. In the Production Forest area, under Perum Perhutani’s supervision, local people started cultivating coffee in-between forest trees and on forest lands that were overgrown with shrubs (Figure 4). The latter was a forest area encroached on and illegally planted with vegetables by the local community.

Figure 4.

Coffee grown between Rasamala trees or in open forest lands and the arabica coffee and the Yellow Columbian coffee fruits.

After almost two decades, coffee cultivation in collaboratively managed forest areas has contributed significantly to coffee bean production in Java, particularly in the West Java Province. West Java’s coffee bean production in 2000 amounted to 6218 tons. Coffee bean production increased to 13,783 tons in 2010 and 21,845 tons in 2020, more than 3 times the coffee bean production before the implementation of the PHBM [34,35,36]. One-third of the coffee beans produced in West Java was the production of Bandung District, harvested mostly from forest areas. The increase in coffee bean production in West Java should be much higher than the reported data. Accurate recording of the coffee bean production was nonexistent due to, among other things, the involvement of many farmers with small production scales and irregular marketing systems.

3. Results

3.1. Brief Description of a Forest Village Community Organization in Bandung District

The introduction of the PHBM program by Perum Perhutani in the study area began in 2004. Several community representatives attended various meetings on collaborative forest management and coffee cultivation training. In 2005, accompanied by Community Facilitators appointed by the Perum Perhutani, the representatives of residents of Lebak Muncang Village formed a forest village community organization (Lembaga Masyarakat Desa Hutan or LMDH).

In the early years of the formation of LMDH, the number of members reached about 500 people. The number increased over time. In 2020, the number of LMDH members was around 1000 people. They were from three villages in three different sub-districts. The majority of LMDH’s members were people of Lebak Muncang Village, Ciwidey District, and Bandung Regency. The rest were people of Alam Endah Village, Rancabali Sub-district, Bandung District, and people of Mekarwangi Village, Sindangkerta District, and West Bandung District (see Figure 1).

3.2. The Ecological Condition of the Forest before and after PHBM

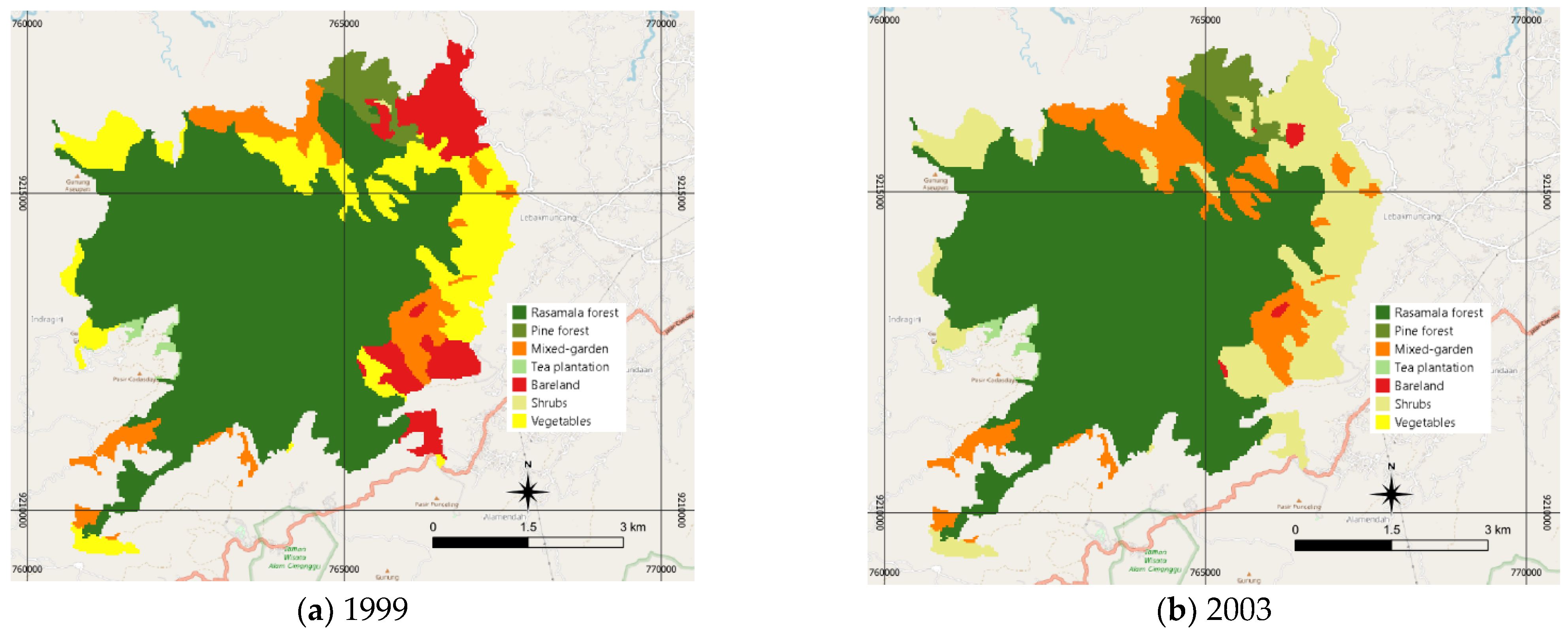

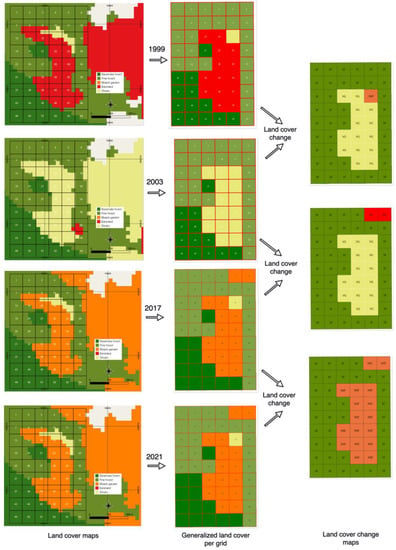

The ecological condition of the forest in the study area underwent a significant change. Before the PHBM program implementation, the forest area was encroached upon by local people and cultivated with vegetables. As presented in Table 1, in 1999, around 24.3% (809.45 ha) of land cover was vegetable land and bare land.

Table 1.

Land Cover Changes, 1999–2021.

The land cover in the form of vegetable fields changed almost entirely to shrubs after the government forcibly stopped illegal cultivation activities in 2000/1 (Table 1). In 2005/6, those involved in the PHBM program changed the shrubs to be planted with coffee and intercropping plants with an agroforestry system. They also cultivated coffee in between the Rasamala trees (Altingia excelsa Noronha) and Pine trees (Pinus merkusii Jungh. & de Vriese) (Figure 5). Data in 2017 showed an increase in land cover in the form of mixed-garden/agroforestry that reached about 29% of the forest area of Lebak Wangi Village. The data in Table 1 show that there is almost no more land cover in the form of shrubs. The vast shrubs turned into agroforestry land. The Perum Perhutani planted pines while farmers planted coffee, some other fruit trees, and intercrops in between the pine and Rasamala trees. Pine trees planted by Perum Perhutani were looked after by the farmers.

Figure 5.

Coffee planted under Rasamala and Pine trees.

Data in Table 1 also show an increase in the Rasamala forest area from 2163.74 ha (64.77%) in 1999 to 2210.17 ha (66.16%) in 2017. The forest area was likely to remain unchanged in 2021 (see Figure 6). The data imply that since PHBM implementation, pressure on the forest has decreased drastically.

Figure 6.

Land cover of forest area in Lebak Muncang Village.

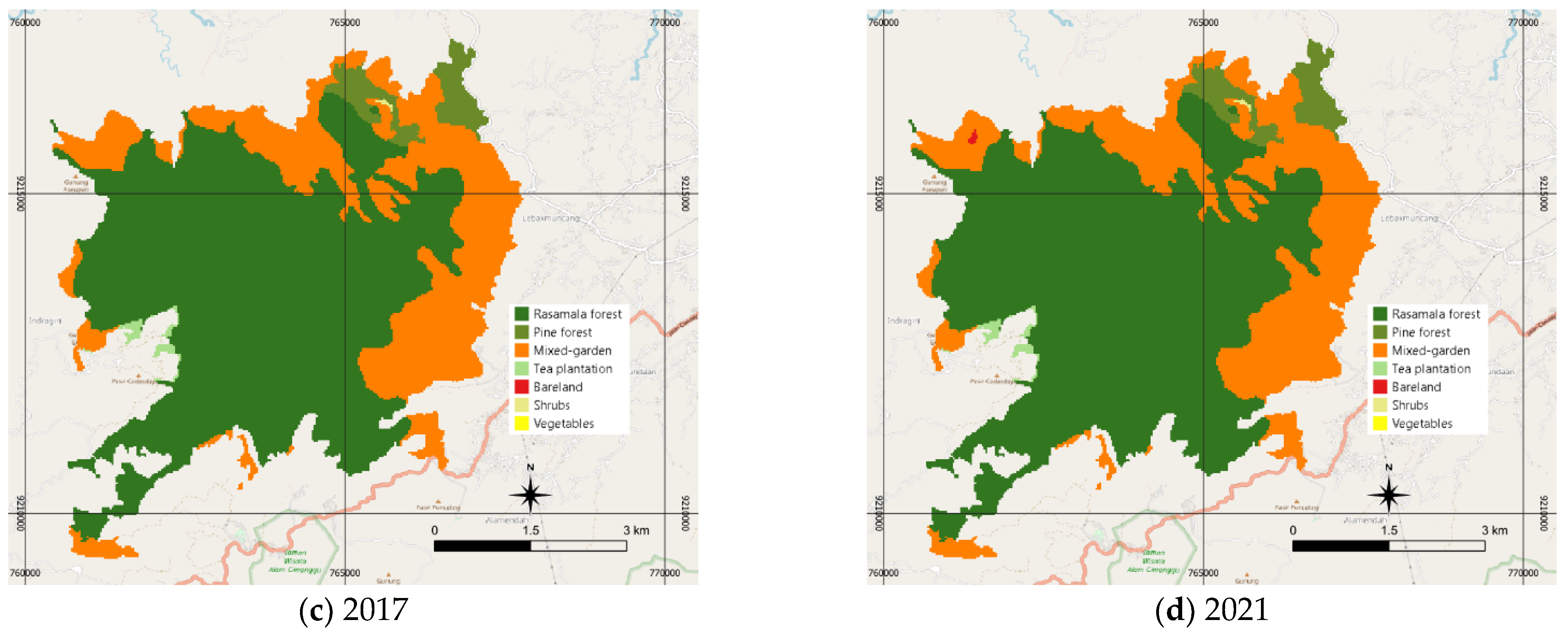

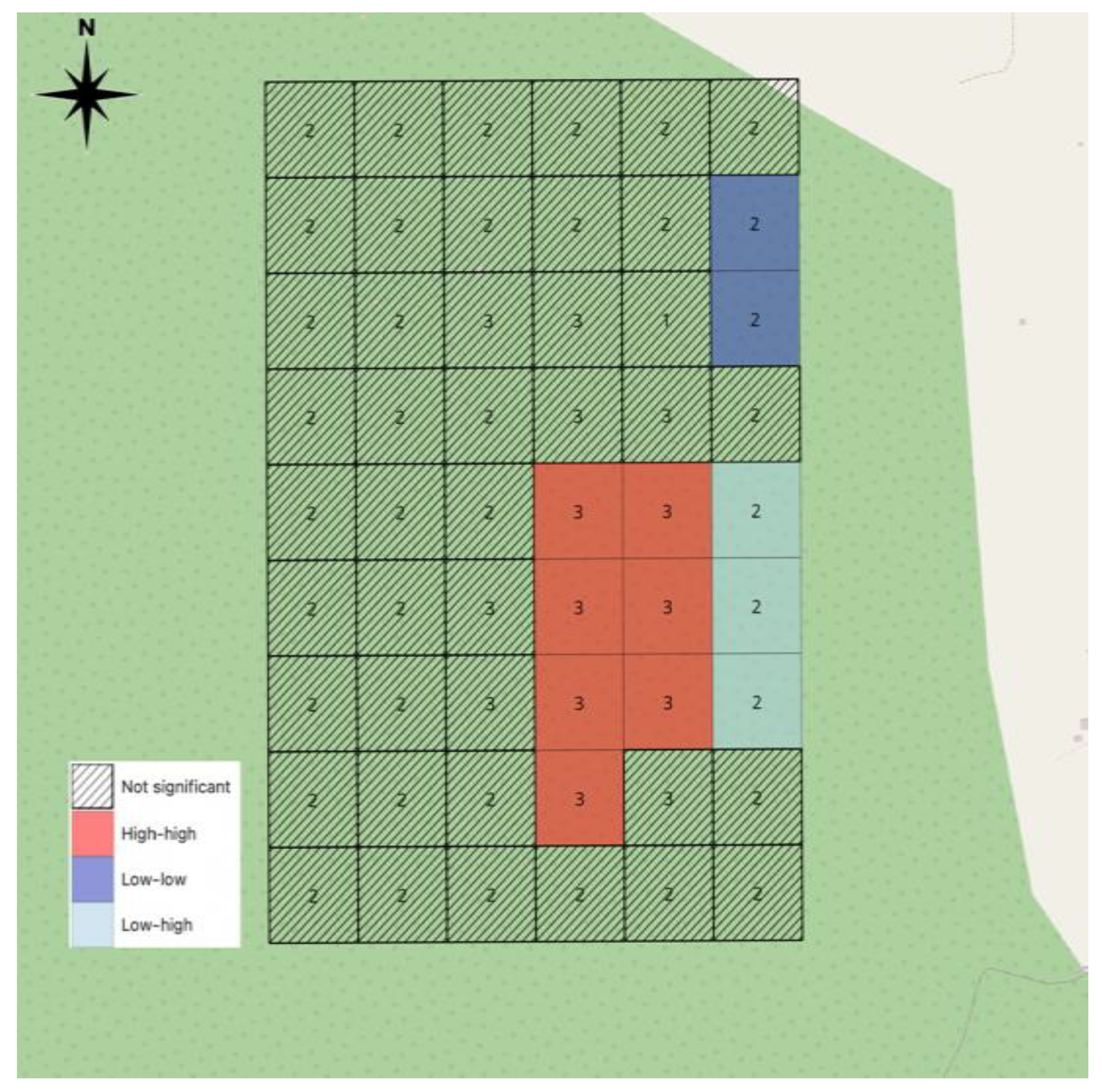

On a patch scale of 54 hectares, bare land or vegetable gardens which were quite extensive in 1999, turned into shrubs in 2003, and changed to mixed-garden/agroforestry in 2017–2021. Following the criteria developed by some scholars [25], a vegetation gain occurred in the forest areas. Vegetation cover increased by around 25,93%. Figure 7 shows the process of analyses of the land cover maps for patch scale derived from landscape-level cover maps.

Figure 7.

Land cover maps of 1999, 2003, 2017, and 2021 in patch scale.

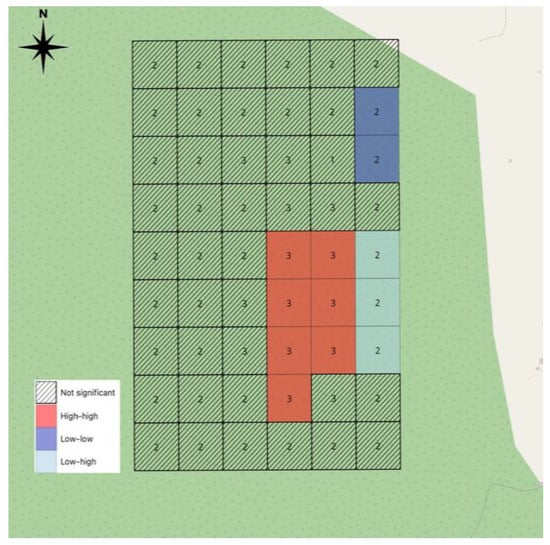

Changes in land cover did not occur because of something random in nature, as evidenced by the results of geostatistical analysis using Local Moran’s I that proves the presence of positive spatial autocorrelation (high-high and low-low) (Figure 8). The transition probability matrices of land cover changes of the 54 hectares of forestland between 1999 and 2021 are presented in Table A1, Table A2 and Table A3.

Figure 8.

Moran’s I Cluster Map of Land Cover Change in the study area.

Vegetation identification on a forest area of 54 hectares shows the composition of vegetation consisting of forest stands, understory vegetation, and cultivated plants. The vegetation composition that made up forest stands consisted of 47 species from 23 plant families (Table A4), understory vegetation consisted of 67 species belonging to 42 families (Table A5), and cultivated plants consisted of 46 types of cultivated plants belongings to 28 families (Table A6).

3.3. PHBM and Community Livelihood

3.3.1. Access to the Forest Lands

Community access in forest management is one of the main issues related to the PHBM program. In-depth interviews with informants indicate that in the early years of the PHBM program, many farmers relinquished their rights to others because they did not have sufficient capital to cultivate coffee and other crops. They relinquished their rights after clearing land to other people for some compensation. It was forbidden to do so. However, Perum Perhutani could not prevent the practice of “transferring or taking over” the cultivated land. This practice was known among the community as ngaleper, transferring or taking over the management rights of someone with a certain amount of compensation money.

On the other hand, the financial difficulties faced by poor farmers did not make many of them despair and gave up their rights to utilize forest lands. In-depth interviews with informants revealed that poor farmers could overcome the lack of capital by working as laborers for wealthy farmers who were also involved in the PHBM program. The laborers worked from morning until noon to earn wages. In the afternoon, they worked on their claimed forestlands, clearing the shrubs and planting coffee, fruit trees, and other intercropping plants.

The laborers had been working for the wealthy farmers for a long time. The two parties depended on each other though their positions were not equal. It looked like a relationship between client and patron. This patronage relationship gave the poor opportunities to earn wages which they used to buy coffee seeds. By doing this the poor farmers could utilize and secure their rights and access to the forestland.

The data in Table 2 show that most of the interviewed households were landless (70.8%). Out of this, 31.3% were those who joined the PHBM program in the early years of the PHBM program. They were the laborers who worked for the wealthy farmers clearing shrubs and planting coffee and other intercropping plants. They were later involved in the PHBM program in 2005-6. Data on the table also indicates that less than half of the interviewed households were members of the forest farmer group who joined the PHBM program after they got the managed forest lands from their parents or after they took over the management rights of someone.

Table 2.

Land ownership based on forest cultivation status (N = 48).

The farmers involved in the PHBM program in Lebak Muncang Village claimed to acquire lands in the forest as large as they could manage once the program started. Some farmers even claimed forest land up to more than 10 hectares. Part of the forestlands they claimed was then “given” to their children. The data in Table 2 show that about 25% of the interviewed farmers stated that they obtained the right to manage the forest lands from their landless parents. The average forest area managed by each member of the farmer group was about 6000 m2. Of the interviewed farmers, 54.2% occupied forest land below the average. Another 45.8% occupied forest land above the average.

With the average of managed forest lands, the farmers planted between 3000 to 5000 coffee trees. This way was not following the rules of coffee cultivation. Field observations show that the distance between coffee trees planted by farmers was generally between 1 × 1 m to 1.5 × 1.5 m. The density of planted coffee trees was very dense. But the farmers believed that they could get more harvest.

Another problem identified in the field was planting uncertified coffee seeds. Many poor farmers planted uncertified coffee seeds because they did not have sufficient capital to buy certified coffee seeds. They collected coffee seeds that grew naturally under coffee trees that had produced coffee cherries and planted the seeds on vacant land or to replace coffee trees that were no longer productive or dead. The death of coffee trees under ten years old was a common phenomenon. Farmers believed this because they planted uncertified coffee seeds.

3.3.2. Livelihood

Since the PHBM program implementation, the livelihoods of the interviewed forest farmer group members changed significantly. Before the PHBM program, data shows that only a few group members worked as farmers on their owned agricultural land or other people’s agricultural lands (33.4%). Most of them worked as farm laborers (37.5%) or other jobs in the non-agricultural sector (29.1%). After the PHBM program implementation, the majority of the farmers interviewed (95.8%) had a source of income merely or partially from the forest land they managed. The rest (4.2%) did not or had not received any income from the coffee trees they owned (Table 3).

Table 3.

Sources of living after PHBM program (N = 48).

In addition to involving many households from villages around the forest as coffee farmers, PHBM activities also involved many other people who did various jobs related to coffee cultivation activities. The study identified several types of work related to coffee cultivation activities (Table 4 and Figure 9). Indirectly, the development of coffee cultivation activities also boosted the wider community’s economy at the village level.

Table 4.

Several types of work related to coffee cultivation activities.

Figure 9.

Coffee picker, coffee transportation, and laborers in coffee bean processing unit.

4. Discussion

Our analyses show two crucial issues related to the implementation of the PHBM program: the impact of PHBM and the access of poor and landless farmers to forest management.

4.1. Impacts of PHBM

The study results show that community involvement in forest management, as indicated in Table 1, increased forest cover in the study area by around 24.19% (Rasamala forest, pine forest, and agroforestry). PHBM activities also changed forest condition from bare lands to agroforestry land as an ecological succession phenomenon. These are similar to a study that stated that community involvement in forest management correlated with the improvement of forest condition [37]. Moreover, the findings also show a change in composition structure of vegetation from simple to more complex vegetation structure and an increase in plant diversity (Table A4 and Table A5). This change in the composition of the vegetation plays a significant role in the balance of an ecosystem, as a source of habitat nutrients and habitat for insects, birds, and mammals. Its abundance and composition affect several ecological processes, including fire and erosion [38]. It means that the PHBM program can contribute to forest conservation and protection due to the PHBM program preventing deforestation and expanding forest cover. This finding is also in line with the research findings of a study in forest areas in other districts in West Java [39] and various findings in other countries.

Based on the results of reviewed cases in several countries, some scholars stated that there was evidence of improved forest conservation and water management related to CFM [40]. In Uganda, the CFM program could improve the forest status or condition and lowered incidences of human disturbances [41]. Meanwhile, in Malawi, the co-managed plots had higher tree density than state-managed plots [42].

As important as the impact of PHBM on forest conservation, PHBM also improved the farmers’ livelihoods. As explained in the results, before the implementation of PHBM, only 33.4% of the people interviewed worked as farmers on their owned land or others owned land as sharecroppers. After the PHBM implementation, most of the interviewed household heads (95.8%) worked as farmers on agroforestry lands they managed in the forest area (Table 3). They also earned sufficient income to meet their daily needs from the intercrops they planted when they started growing coffee, or even after their coffee trees produced coffee cherries (see Table A6). The data also show that many people benefited from PHBM program; the coffee farmers, the laborers who got wages from caring for coffee trees, coffee pickers who worked at harvest, or motorcycle taxi drivers who transported coffee harvests from the forest (Table 4). The PHBM program has created various economic multiplier effects in the surrounding area of PHBM activities.

The findings of this study are in line with the findings of other studies in Ethiopia, Kenya, and South Korea. Under a participatory management arrangement in southern Ethiopia, forest resources contributed to the livelihoods of rural households [43]. In general, the result confirms the importance of forest income in poverty alleviation and as safety nets in times of income crisis. In Kenya, collaborative forest management programs improved people’s livelihoods [44]. A recent study from South Korea mentioned that CFM participating households were likely to have a higher income than non-CFM participating households [45].

4.2. Rights and Access to the Forest

The PHBM program provides opportunities for people around the forest to be involved in collaborative forest management. The results of the study show that among the interviewed farmers, 70.8% were landless (Table 2). Before being involved in the PHBM program, many interviewed farmers who worked in agricultural sector as farm laborers had no capital to plant coffee and practice agroforestry in forest areas. By taking advantage of the patronage relationships they had with some wealthy farmers, they could utilize the forest land and maintain their rights and access to the forest area.

The result of this study is different from the statement put forward by several researchers who argue that the economic benefits of the CFM go to the rich more, the poorer groups have poorer access to the forest, and there is no guarantee that the benefits flow to local communities [41,46]. They further argue that the elites dominate access to resources. These are due to weaknesses in local governance and implementation of CFM initiatives, including poor accountability and no systematic monitoring.

This study found that the poor and the landless faced more difficulties than the wealthier farmers in developing agroforestry in the forest area. However, it did not mean that they had to relinquish their rights and access to the PHBM program. This study found the landless farmers succeeded in utilizing and securing their rights to the forest. By leveraging their social capital and patronage relationships with wealthy farmers, the landless farmers could keep their access to forest areas. After several years of growing coffee, they transformed themselves from farm laborers to coffee farmers. Utilization of social capital was a way for the laborers to maintain their rights and access to forest management systems when direct support from the government or forest management was not available. In this regard, some scholars mention that social capital is a determinant of successful community forest management for the sustainability of forests and communities [47]. A study from Nepal showed that Pengelolaan Hutan Bersama Masyarakat patron–client relationship matters in ensuring people’s participation in social forestry. The poor farm laborers gained access to forest management facilitated by the rich farmers who were their patrons [48].

The study results show that the poor or landless farmers, by optimizing the patron–client relationships, could change their lives from laborers to coffee farmers. However, there is no guarantee that they will continue maintaining their rights and access to the forestland. A coffee-based agroforestry system requires capital that poor farmers cannot always fulfill. In addition, for poor farmers or landless farmers who do not have strong patronage relationships with wealthy farmers or certain other parties, it is unlikely that they will be able to utilize and maintain the forestland to which they are entitled because they do not have sufficient capital to practice agroforestry.

In that regard, support from the government is necessary. The government must have programs that support the poor or the landless farmers to utilize and maintain their rights and access to the forestland. A kind of long-term soft loan is very likely to be needed. This program can be an alternative to protect the rights and access of the poor or landless farmers to collaborative forest management. A case of provision of micro-credits in the Adaptive Collaborative Forest Management program in Nepal that has increased the opportunity of the poor people to benefit from forest management can be referred to [49]. Accordingly, identification the socio-economic characteristics of the people living surrounding the forest areas to give priority to the poor or landless farmers to be involved and supported in the development of collaborative forest management is important to carry out.

5. Conclusions

This study documents that involvement of the local people in forest management is an appropriate policy. This study raises two main issues: the impact of, and the local community rights and access to, collaborative forest management. Ecologically, collaborative forest management could improve forest conditions, as indicated by the increased forest cover. The application of an agroforestry system has increased plant diversity in forest areas. The study findings support the idea that granting certain tenure rights to the community will encourage community members to manage forest resources properly. The collaborative forest management system also contributes positively to the improvement of the livelihoods of the people involved and even contributes to economic development on the regional scale.

Regarding community rights and access, this study concludes that the case of collaborative forest management in the study area indicates that rights and opportunities for the community to access the program are not only obtained by those who are relatively economically secure but also by those who are poor or landless. Moreover, the study also identified that the poor or landless farmers could maintain their rights and access to collaborative forest management system by utilizing patronage relationships with wealthy farmers. However, the study also suggests that there is no guarantee that those who have patronage relationships with local elite groups will continue to utilize the forestland. Therefore, government support is needed to protect their rights and access to the collaborative forest management system.

6. Postscript

Forest management in Indonesia has fundamentally changed in terms of community access to forests. In 2016, the Ministry of Environment and Forestry issued a ministerial regulation on a new Social Forestry program that applies throughout Indonesia (the third generation of Social Forestry program). In Java, the Ministry of Environment and Forestry issued special regulation on the social forestry program in the Perum Perhutani Working Area, ministerial regulation No. P.39/MENLHK/SETJEN/KUM.1/6/2017. By this regulation, the government permits the people to manage the forests for 35 years and evaluates this permit every 5 years. Under this regulation, since 2017/18, a few LMDHs in South Bandung Forest Management Unit have been provided with the Forest Utilization Permit. Most of the LMDH were still collaborating with the Perum Perhutani, under the PHBM scheme.

With the implementation of the new Social Forestry program, several questions arise regarding the outcome of the new program on forest conservation and the socio-economic conditions of people. The sustainability of forest management under the new paradigm is important to study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: B.G.; Data collection: B.G., I.Y.A., R.N.S., G.J.A., F.H. and W.G.; Analysis: B.G., O.S.A. and F.H.; Writing: B.G., O.S.A., F.H. and G.J.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by research grant from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology, Republic of Indonesia. Contract No. 136/E4.1/AK.04.PT/2021; 1347/UN6.3.1/PT.00/2021.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

This study is a non-interventional study. We conducted interviews, observations, and household surveys. We explained to all the informants and households participating in the study about the research and asked for their permission and willingness to participate in this research.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Perum Perhutani, particularly the KPH Bandung Selatan, the villages apparatus, the LMDH Tambaga Ruyung, H. Arifin, Pendi, and Djadja for the information and accommodation provided to the study team during the fieldwork and the coffee farmers for their willingness to respond our questions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Transition probability matrix of land cover change from 1999 and 2003.

Table A1.

Transition probability matrix of land cover change from 1999 and 2003.

| Rasamala | Pine | Mixed-Garden | Bareland | Shrubs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rasamala | 0.750 | 0 | 0 | 0.125 | 0.125 |

| Pine | 0.118 | 0.588 | 0 | 0.118 | 0.176 |

| Mixed-garden | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bareland | 0.071 | 0.357 | 0 | 0.571 | 0 |

| Shrubs | 0.063 | 0.438 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 |

Table A2.

Transition probability matrix of land cover change from 2003 and 2017.

Table A2.

Transition probability matrix of land cover change from 2003 and 2017.

| Rasamala | Pine | Mixed-Garden | Bareland | Shrubs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rasamala | 0.750 | 0 | 0.125 | 0 | 0.125 |

| Pine | 0.121 | 0.576 | 0.121 | 0 | 0.182 |

| Mixed-garden | 0.067 | 0.400 | 0.533 | 0 | 0 |

| Bareland | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Shrubs | 0.063 | 0.438 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 |

Table A3.

Transition probability matrix of land cover change from 2017 and 2021.

Table A3.

Transition probability matrix of land cover change from 2017 and 2021.

| Rasamala | Pine | Mixed-Garden | Bareland | Shrubs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rasamala | 0.894 | 0 | 0.074 | 0 | 0 |

| Pine | 0.032 | 0.894 | 0.063 | 0 | 0.011 |

| Mixed-garden | 0.052 | 0.107 | 0.829 | 0 | 0.012 |

| Bareland | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Shrubs | 0 | 0.250 | 0.188 | 0 | 0.563 |

Table A4.

Forest stand composer plants.

Table A4.

Forest stand composer plants.

| Family | No. | Local Name | Scientific Name |

|---|---|---|---|

| Actinidiaceae | 1 | Ki leho | Saurauia bracteosa DC. |

| Altingiaceae | 2 | Rasamala | Altingia excelsa Noronha |

| Araliaceae | 3 | Cerem | Macropanax dispermus (Blume) Kuntze |

| Araucariaceae | 4 | Damar | Agathis dammara (Lamb.) Rich. & A. Rich. |

| Cannabaceae | 5 | Kurai | Trema orientalis (L.) Blume |

| Cyatheaceae | 6 | Paku tiang | Cyathea contaminans (Wall. ex Hook.) Copel. |

| Elaeocarpaceae | 7 | Tebe | Sloanea sigun (Blume) K. Schum. |

| 8 | Kareumbi | Homalanthus populneus (Geiseler) Pax. | |

| 9 | Manggong | Macaranga rhizinoides (Blume) Mull. Arg. | |

| Euphorbiaceae | 10 | Mara | Macaranga tanarius (L.) Mull. Arg. |

| 11 | Waru gunung | Homalanthus giganteus Zoll. & Moritzi | |

| 12 | Hiur sapu | Castanopsis javanica (Blume) A. DC. | |

| 13 | Kiriung | Castanopsis acuminatissima (Blume) A. DC. | |

| 14 | Pasang beureum | Quercus lineata Blume | |

| 15 | Pasang gebod | Lithocarpus indutus (Blume) Rehder | |

| 16 | Pasang jambe | Quercus gemelliflora Blume | |

| Fagaceae | 17 | Pasang mempening | Quercus argentata Korth. |

| 18 | Pasang taritih | Lithocarpus elegans (Blume) Hatus. ex Soepadmo | |

| 19 | Saninten | Castanopsis argentea (Blume) A. DC. | |

| 20 | Tunggereuk | Castanopsis tungurrut (Blume) A. DC. | |

| Hammelidaceae | 21 | Ki tambaga | Distyllum stellare Kuntze |

| 22 | Huru minyak | Litsea resinosa Blume | |

| Lauraceae | 23 | Huru perak | Phoebe grandis (Ness) Merr. |

| 24 | Ki teja | Cinnamomum iners Reinw. ex Blume | |

| Magnoliaceae | 25 | Baros | Magnolia sumatrana var. glauca (Blume) Figlar & Noot. |

| 26 | Kedoya | Dysoxylum gaudichaudinum (A. Juss.) Miq. | |

| 27 | Mindi | Melia azedarach L. | |

| Meliaceae | 28 | Pisitan monyet | Dysoxylum alliaceum (Blume) Blume |

| 29 | Suren | Toona sureni (Blume) Merr. | |

| 30 | Beunying | Ficus fistulosa Reinw. ex Blume | |

| 31 | Hamerang | Ficus padana Burm. f. | |

| Moraceae | 32 | Kondang | Ficus variegata Blume |

| 33 | Walen | Ficus ribes Reinw. ex Blume | |

| 34 | Ki bodas | Eucalyptus urophylla S. T. Blake | |

| 35 | Ki beusi | Rhodamnia cinerea Jack | |

| Myrtaceae | 36 | Ki salam | Syzygium lineatum (DC.) Merr. & L. M. Perry |

| 37 | Salam hutan | Syzygium polyanthum (Wight) Walp. | |

| Pinaceae | 38 | Pinus | Pinus merkusii Jungh. & de Vriese |

| Piperaceae | 39 | Seuseureuhan | Piper aduncum L. |

| 40 | Jamuju | Dacrycarpus imbricatus (Blume) de Laub. | |

| Podocarpaceae | 41 | Ki putri | Podocarpus neriifolius D. Don |

| Rhamnaceae | 42 | Manii | Maesopsis eminii Engl. |

| 43 | Kikopi | Canthium aciculatum Ridl. | |

| Rubiaceae | 44 | Ki cengkeh | Urophyllum arboreum (Reinw. ex Blume) Korth. |

| Sapindaceae | 45 | Huru kapas | Acer laurinum Hassk. |

| Theaceae | 46 | Puspa | Schima wallichii Choisy |

| Urticaceae | 47 | Nangsi | Oreocnide rubescens (Blume) Miq. |

Table A5.

Types of plants that make up forest floor coverings.

Table A5.

Types of plants that make up forest floor coverings.

| Family | No. | Local Name | Scientific Name |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acanthaceae | 1 | Bubukuan | Strobilanthes cernua Blume |

| Apiaceae | 2 | Pegagan | Centella asiatica (L.) Urb. |

| 3 | - | Arisaema sp. | |

| Araceae | 4 | Suweg | Amorphophallus spectabilis (Miq.) Engl. |

| 5 | Bingbin | Pinanga coronata (Blume ex Mart.) Blume | |

| Arecaceae | 6 | Bubuay | Plectocomia elongata Mart. ex Blume |

| 7 | Sarai | Caryota mitis Lour. | |

| Aspleniaceae | 8 | Paku sarang burung | Asplenium sp. |

| 9 | Begonia | Begonia bracteata Jack | |

| Begoniaceae | 10 | Begonia | Begonia muricata Blume |

| 11 | Hariang | Begonia isoptera Dryand. ex Sm. | |

| Campanulaceae | 12 | - | Codonopsis javanica (Blume) Hook. f. & Thomson |

| Cannabaceae | 13 | Ki tamiang | Celtis timorensis Span. |

| Commelinaceae | 14 | - | Amischotolype mollissima (Blume) Hassk. |

| 15 | - | Chromolaena odorata (L.) R. M. King & H. Rob. | |

| Compositae | 16 | Kirinyuh | Eupatorium inulifolium Kunth |

| 17 | Teklan | Ageratina riparia (Regel) R. M. King & H. Rob | |

| Costaceae | 18 | Pacing | Cheilocostus speciosus (J. Konig) C. Specht |

| Cyperaceae | 19 | Areuy | Cyperus sp. |

| 20 | Paku harupat | Nephrolepis sp. | |

| Davalliacaeae | 21 | - | Davallia sp. |

| Euphorbiaceae | 22 | Waru gunung | Homalanthus giganteus Zoll. & Moritzi |

| Gesneriaceae | 23 | - | Cyrtandra pendula Blume |

| Gleicheniaceae | 24 | Paku andam | Dicranopteris linearis (Burm. f.) Underw. |

| Hypoxidaceae | 25 | Daun congkok | Molineria capitulata (Lour.) Herb. |

| 26 | Carulang | Spatholobus ferrugineus (Zoll. & Moritzi) Benth. | |

| Leguminosae | 27 | Jeunjing laut | Falcataria mollucana (Miq.) Barneby & J. W. Grimes |

| 28 | Kaliandra | Calliandra calothyrsus Meisn. | |

| Loranthaceae | 29 | Benalu belimbing | Macrosolen cochinchinensis (Lour.) Tiegh. |

| Malvaceae | 30 | Hantap | Sterculia rubiginosa Zoll. ex Miq. |

| Marantaceae | 31 | - | Phyrnium sp. |

| 32 | Harendong | Astronia macrophylla Blume | |

| 33 | Harendong | Melastoma malabathricum L. | |

| Melastomataceae | 34 | Harendong bulu | Clidemia hirta (L.) D. Don |

| 35 | Parijoto | Medinilla speciosa Blume | |

| Myrtaceae | 36 | Salam hutan | Syzygium polyanthum (Wight) Walp. |

| Oleandraceae | 37 | - | Oleandra pistillaris (Sw.) C. Chr. |

| Pandanaceae | 38 | Pandan hutan | Pandanus furcatus Roxb. |

| 39 | Katuk | Sauropus androgynus (L.) Merr. | |

| Phyllanthaceae | 40 | Ki seueur | Antidesma montanum Blume |

| 41 | - | Breynia sp. | |

| Phytolaccaceae | 42 | Buah tinta | Phytolacca americana L. |

| Piperaceae | 43 | - | Peperomia laevifolia (Blume) Miq. |

| Polygalaceae | 44 | - | Polygala venenosa Juss. ex Poir. |

| Primulaceae | 45 | - | Ardisia villosa Roxb. |

| 46 | Paku | Pteris sp. | |

| Pteridophytes | 47 | - | Dipteris conjugata Reinw. |

| 48 | Hareueus | Rubus buergeri Miq. | |

| Rosaceae | 49 | Kawoyang | Prunus arborea (Blume) Kalkman |

| Rubiaceae | 50 | - | Mycetia cauliflora Reinw. |

| 51 | - | Ophiorrhiza longiflora | |

| 52 | Ki cengkeh | Urophyllum arboreum (Reinw. ex Blume) Korth. | |

| Rutaceae | 53 | Ki jeruk | Acronychia pedunculata (L.) Miq. |

| Salicaceae | 54 | Rukem | Flacourtia rukam Zoll. & Moritzi |

| Selaginellaceae | 55 | Rane | Selaginella sp. |

| 56 | Canar | Smilax leucophylla Blume | |

| Smilacaceae | 57 | Canar | Smilax macrocarpa Blume |

| Solanaceae | 58 | Terong belanda | Solanum betaceum Cav. |

| Symplocaceae | 59 | Jirak | Symplocos ramosissima Wall. ex G. Don |

| 60 | - | Elatostema sp. | |

| 61 | - | Gonostegia hirta (Blume ex Hassk.) Miq. | |

| Urticaceae | 62 | Pohpohan | Pilea melastomoides (Poir.) Wedd. |

| 63 | Pulus | Dendrocnide sinuata (Blume) Chew | |

| 64 | Jalatong | Dendrocnide stimulans (L. f.) Chew | |

| 65 | Totongoan | Debregeasia longifolia (Burm. f.) Wedd. | |

| Verbenaceae | 66 | Saliara | Lantana camara L. |

| Zingiberaceae | 67 | Tepus | Etlingera coccinea (Blume) S. Sakai & Nagam. |

Table A6.

Types of cultivated plants.

Table A6.

Types of cultivated plants.

| Family | No. | Local Name | Scientific Name |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anacardiaceae | 1 | Jambu mete | Anacardium occidentale L. |

| 2 | Kedondong | Spondias dulcis L. | |

| 3 | Limus | Mangifera foetida Lour. | |

| 4 | Mangga | Mangifera indica L. | |

| 5 | Sarikaya | Annona squamosa L. | |

| Annonaceae | 6 | Sirsak | Annona muricata L. |

| 7 | Tapakdara | Catharanthus roseus (L.) G.Don | |

| Apocynaceae | 8 | Talas | Caladium sp. |

| Arecaceae | 9 | Aren | Arenga pinnata Merr. |

| Asteraceae | 10 | Sintrong | Crassocephalum crepidioides Hiern. |

| Athyriaceae | 11 | Paku Sayur | Diplazium esculentum Sw. |

| Balsaminaceae | 12 | Pacar air | Impatiens balsamina L. |

| Bombacaceae | 13 | Duren | Durio zibethinus L. |

| Caricaceae | 14 | Pepaya | Carica papaya L. |

| Brassicaceae | 15 | Kubis | Brassica oleracea L. |

| Euphorbiaceae | 16 | Singkong | Manihot esculenta Crantz |

| 17 | Asam jawa | Tamarindus indica L. | |

| Fabaceae | 18 | Petai | Parkia peciosa Hassk. |

| 19 | Kacang Tanah | Arachis hypogaea L. | |

| Lamiaceae | 20 | Kemangi | Ocimum x citriodorum |

| Lauraceae | 21 | Alpukat | Persea americana Mill. |

| Laxmanniaceae | 22 | Hanjuang | Cordyline fruticosa A. Chev. |

| Marsileaceae | 23 | Semanggi | Marsilea crenata C. Presl |

| Mimosaceae | 24 | Lamtoro | Leucaena lecocephala de Wit |

| Moraceae | 25 | Nangka | Artocarpus heterophyllus Lam. |

| Musaceae | 26 | Pisang | Musa x paradisiaca |

| 27 | Jambu batu | Psidium guajava L. | |

| Myrtaceae | 28 | Jambu air | Syzigium aquea Alston |

| Piperaceae | 29 | Seureuh | Piper betle L. |

| Poaceae | 30 | Kaso | Saccharum spontaneum L. |

| Rubiaceae | 35 | Kopi | Coffea arabica L. |

| Rutaceae | 36 | Jeruk purut | Citrus hystrix DC. |

| Sapindaceae | 37 | Lengkeng | Dimocarpus longan Lour. |

| Sapotaceae | 38 | Sawo | Manilkara zapota P. Royen |

| 39 | Cabai rawit | Capsicum frutescens | |

| 40 | Terong | Solanum melongena L. | |

| Solanaceae | 41 | Leunca | Solanum nigrum L. |

| 42 | Takokak | Solanum rudepandum G. Forst. | |

| 43 | Kentang | Solanum tuberosum L. | |

| 44 | Combrang | Etlingera aelatior R. M. Sm. | |

| 45 | Jahe | Zingiber officinale Roscoe | |

| Zingiberaceae | 46 | Kapolaga | Amomum compactum Soland ex Maton |

References

- Agrawal, A.; Gibson, C.C. Enchantment and disenchantment: The role of community in natural resource conservation. World Dev. 1999, 27, 629–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromley, D.W.; Cernea, M. The Management of Common Property Natural Resources Some Conceptual and Operational Fallacies; World Bank Discussion Paper, No. 57; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Tole, L. Reforms from the Ground Up: A Review of Community-Based Forest Management in Tropical Developing Countries. Environ. Manag. 2010, 45, 112–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, J.C.; Gronow, J. Recent Experience in Collaborative Forest Management a Review Paper; Cifor Occasional Paper, No. 43; Center for International Forestry Research: Bogor, Indonesia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Klooster, D.; Masera, O. Community forest management in Mexico: Carbon mitigation and biodiversity conservation through rural development. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2000, 10, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, B.; Di Falco, S.; Lovett, J.C. Household characteristics and forest dependency: Evidence from common property forest management in Nepal. Ecol. Econ. 2003, 48, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, E.J.Z.; Albers, H.J.; Meschak, C.; Lokina, R. Implementing REDD through community-based forest management: Lesson from Tanzania. Nat. Resour. Forum. 2013, 37, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kedir, H.; Negash, M.; Yimer, F.; Lemenih, M. Contribution of participatory forest managemet towards conservation and rehabilitation of dry Afromontane forests and its implications for carbon management in the tropical Southeastern Highlands of Ethiopia. J. Sustain. For. 2018, 37, 357–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santika, T.; Meijaard, E.; Budiharta, S.; Law, E.A.; Kusworo, A.; Hutabarat, J.A.; Indrawan, T.P.; Struebig, M.; Raharjo, S.; Huda, I.; et al. Community forest management in Indonesia: Avoided deforestation in the context of anthropogenic and climate complexities. Glob. Environ. 2017, 46, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobeze, T.; Bekele, M.; Lemenih, M.; Kassa, H. Participatory forest management and its impact on livelihoods and forest status: The Case of Bonga Forest in Ethiopia. Int. For. Rev. 2009, 11, 346–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, J.; Gelinas, N.; Skutsch, M. The place of community forest management in the REDD+ landscape. Forests 2016, 7, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, T.; Septiana, R.M.; Awang, S.A.; Widayanti, W.T.; Bariatul, H.; Hyakumura, K.; Sato, N. Changes in local social economy and forest management through the introduction of collaborative forest management (PHBM), and the challenges it poses on equitable partnership: A case study of KPH Pemalang, Central Java, Indonesia. Tropics 2012, 20, 115–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawan, B.; Kazuhiko, T.; Tsunekawan, A.; Abdoellah, O. Community Dependency on Forest Resources in West Java, Indonesia: The Need to Re-Involve Local People in Forest Management. J. Sustain. For. 2004, 18, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.M. Engaging smplifications: Community-based resource management, market processes and state agendas in upland Southeast Asia. World Dev. 2002, 30, 265–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowler, D.E.; Buyung-Ali, L.M.; Healey, J.R.; Jones, J.P.G.; Knight, T.M.; Pullin, A.S. Does community forest management provide global environmental benefits and improve local welfare? Front. Ecol. Environ. 2012, 10, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomba, S.; Treue, T.; Sinclair, F. The political economy of forest entitlements: Can community-based forest management reduce vulnerability at the forest margin? Policy Econ. 2015, 58, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Royer, S.; Van Noordwijk, M.; Roshetko, J.M. Does community-based forest management in Indonesia devolve social justice or social costs? Int. For. Rev. 2018, 20, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahanty, S.; Guernier, J.; Yasmi, Y. A fair share? Sharing the benefits and costs of collaborative forest management. Int. For. Rev. 2009, 11, 268–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimengsi, J.N.; Bhusal, P.; Aryal, A.; Fernandez MVB, C.; Owusu, R.; Chaudhary, A.; Nielsen, W. What (De)Motivates Forest Users’ Participation in Co-Management? Evid. Nepal. For. 2019, 10, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumboko, L.; Race, D.; Curtis, A. Optimizing community-based forest management policy in Indonesia: Critical review. J. Ilmu. Sos. Dan Ilmu. Polit. 2013, 16, 250–272. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, M.R.; Dhiaulhaq, A.; Sahide, M.A.K. The politics, economies and ecologies of Indonesia’s thrid generation of social forestry: An introduction to the special section. For. Soc. 2019, 3, 152–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardjono, J. Land, Labour, and Livelihood in a West Java Village; Gadjah Mada University Press: Jogjakarta, Indonesia, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Planet Team. Planet Application Program Interface: In Space for Life on Earth. 2017. Available online: https://api.planet.com (accessed on 12 August 2021).

- Tosiani, A.; Mohammad, A.R.; Sularso, G.N.M.; Lugina, M.; Novita, N.; Lestari, N.S. Standar Operasional; Prosedur Penghitungan Akurasi dan Uncertainty Perubahan Penutupan Lahan (Standard Operational Procedure Calculation of Accuration and Uncertainty of Land Cover Change); Penerbit IPB Press: Bogor, Indonesia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Anselin, L.; Syabri, I.; Kho, Y. GeoDa: An Introduction to Spatial Data Analysis. Geogr. Anal. 2006, 38, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameha, A.; Meilby, H.; Feyisa, G.L. Impacts of participatory forest management on species composition and forest structure in Ethiopia. Int. J. Biodivers. Sci. Ecosyst. Serv. Manag. 2016, 12, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peluso, N.L. Rich Forests, Poor People, and Development: Forest Access Control and Resistance in Java. Ph.D. Dissertation, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Peluso, N.L. A History of state forest management in Java. In Keepers of the Forest. Land Management Alternatives in Southeast Asia; Poffenberger, M., Ed.; Ateneo de Manila University Press: Quezon City, Philippines, 1990; pp. 27–55. [Google Scholar]

- Peluso, N.; Lee, M.P.; Seymor, F. Reorienting forest management on Java. In Keepers of the Forest. Land Management Alternatives in Southeast Asia; Poffenberger, M., Ed.; Ateneo de Manila University Press: Quezon City, Philippines, 1990; pp. 220–236. [Google Scholar]

- Stoney, C.; Bratamihardja, M. Identifying appropriate agroforestry technologies in Java. In Keepers of the Forest. Land Management Alternatives in Southeast Asia; Poffenberger, M., Ed.; Ateneo de Manila University Press: Quezon City, Philippines, 1990; pp. 145–160. [Google Scholar]

- Perhutani, P. Experiences of Perum Perhutani in the implementation of social forestry practices in Java. In Social Forestry and Sustainable Forest Management, Proceedings of the Seminar on the Development of Social Forestry and Sustainable Forest Management, Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 29 August–2 September 1994; Simon, H., Hartadi, S.S., Sumardi, I.S., Eds.; Gadjah Mada University: Jakarta, Indonesia, 1994; pp. 88–95. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, H. The technical and social needs of social forestry. In Social Forestry and Sustainable Forest Management, Proceedings of the Seminar on the Development of Social Forestry and Sustainable Forest Management, Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 29 August–2 September 1994; Simon, H., Hartadi, S.S., Sumardi, I.S., Eds.; Gadjah Mada University: Jakarta, Indonesia, 1994; pp. 75–87. [Google Scholar]

- Ardyanny, F.; Santoso, B.; Cahyaningtyas, I. Aspek Hukum Model Pengelolaan Hutan Bersama Masyarakat (PHBM) [Law Aspect of Collaborative Forest Management Model]. Notarius 2020, 13, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BPS—Statistics of Jawa Barat Province, Jawa Barat Dalam Angka (West Java in Figure) 2000. Available online: https://jabar.bps.go.id/publication.html (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- BPS—Statistics of Jawa Barat Province, Jawa Barat Dalam Angka (West Java in Figure) 2011. Available online: https://jabar.bps.go.id/publication.html (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- BPS—Statistics of Jawa Barat Province, Jawa Barat Dalam Angka (West Java in Figure) 2021. Available online: https://jabar.bps.go.id/publication.html (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Blomley, T.; Pfliegner, K.; Isango, J.; Zahabu, E.; Ahrends, A.; Burges, N. Seeing the wood for the trees: An assessment of the impact of participatory forest management on forest condition in Tanzania. Oryx 2008, 42, 380–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.M.S.; Lentile, L.B.; Hudak, A.T.; Morgan, P. Evaluation of linear spectral unmixing and DNBR for predicting post-fire recovery in a North American ponderosa pine forest. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2007, 28, 5159–5166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasetyo, L.B.; Damayanti, E.K.; Masuda, M. Land Cover Chamges before and after Implementation of the PHBM Program in Kuningan District, West Java, Indonesia. Tropics 2012, 21, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petheram, R.J.; Stephen, P.; Gilmour, D. Collaborative forest management: A review. Aust. For. 2004, 67, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turyahabwe, N.; Tumusiime, D.M.; Byakagaba, P.; Tumwebaze, S.B. Impact of Collaborative Forest Management on Forest Status and Local Perceptions of Contribution to Livelihoods in Uganda. J. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 6, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinangwa, L.L.; Pullin, A.S.; Hockley, N. Impact of forest co-management programs on forest conditions in Malawi. J. Sustain. For. 2017, 36, 338–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yemiru, T.; Roos, A.; Campbel, B.M.; Bohlin, F. Forest incomes and poverty alleviation under participatory forest management in the Bale Highlands, Southern Ethiopia. Int. For. Rev. 2010, 12, 66–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming’ate, F.L.M.; Rennie, H.G.; Memon, A. Potential for co-management approaches to strengthen livelihoods of forest dependent communities: A Kenyan case. Land Use Policy 2014, 41, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-H.; Yeo-Chang, Y. Impact of Collaborative Forest Management on Rural Livelihood: A Case Study of Maple Sap Collecting Households in South Korea. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahanty, S.; Gronow, J.; Nurse, M.; Malla, Y. Reducing poverty through community based forest management in Asia. J. For. Livelihood 2006, 5, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Rianti, I.P.; Park, M.S. Measuring social capital in Indonesian community forest management. For. Sci. Technol. 2017, 13, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.A. Participation in Forestry: The Role of Patron-Client Relationship in Ensuring People’s Participation in the Social Forestry of Bangladesh. Asian Profile 2009, 37, 267–285. [Google Scholar]

- McDougall, C.; Jiggins, J.; Pandit, B.H.; Thapa, S.K.; Rana, M.; Leeuwis, C. Does Adaptive Collaborative Forest Governance Affect Poverty? Participatory Action Research in Nepal’s Community Forests. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2013, 26, 1235–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).