Impact and Mechanisms of Digital Inclusive Finance in Relation to Farmland Transfer: Evidence from China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Direct Impact of Digital Financial Inclusion on Farmland Transfer

2.2. Indirect Impact of Digital Financial Inclusion on Farmland Transfer

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Variable Selection

3.1.1. Explained Variable

3.1.2. Core Explanatory Variable

3.1.3. Mediating Variable

3.1.4. Control Variable

3.1.5. Instrumental Variable

3.2. Model Setting

3.2.1. Baseline Regression

3.2.2. Livelihood Capitals Assessment

3.2.3. Chain Mediation Effect

3.3. Data Sources and Descriptive Statistics

4. Estimated Results and Heterogeneity Test

4.1. Baseline Regression Analysis Results

4.2. Robustness and Endogenous Test

4.2.1. Robustness Test

4.2.2. Endogenous Test

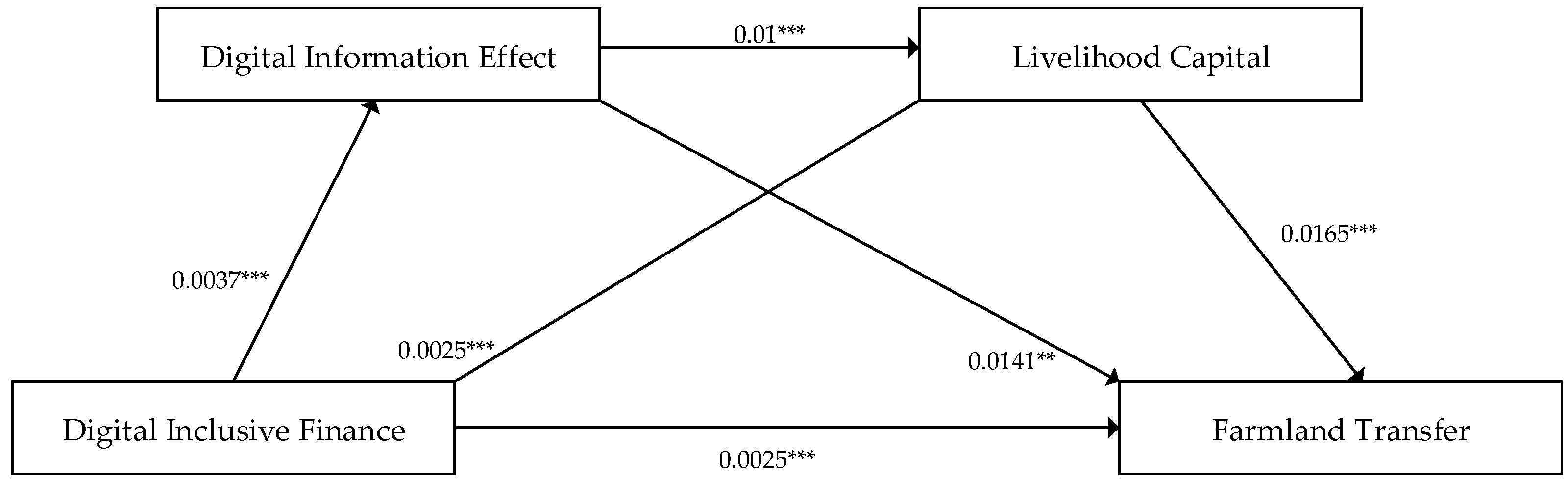

4.3. Mechanism Analysis

4.4. Heterogeneity Analysis

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McMillan, J.; Whalley, J.; Zhu, L. The Impact of China’s Economic Reforms on Agricultural Productivity Growth. J. Political Econ. 1989, 97, 781–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.Y. Rural Reforms and Agricultural Growth in China. Am. Econ. Rev. 1992, 82, 34–51. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, N.; Wang, M.; Liu, Z. Farmland Transfer, Scale Management and Economies of Scale Assessment: Evidence from the Main Grain-Producing Shandong Province in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H.; Su, Q. Does the Use of Digital Finance Affect Household Farmland Transfer-Out? Sustainability 2023, 15, 12103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Zhao, L.; Chen, H.; Zhou, Y.; Lin, H.; Wang, C.; Huang, H.; Li, X.; Yuan, Z. Does Farmland Transfer Lead to Non-Grain Production in Agriculture?—An Empirical Analysis Based on the Differentiation of Farmland Renting-In Objects. Sustainability 2022, 15, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, T.; He, W.; Liu, Z. Exploring the Influence of Land Titling on Farmland Transfer-Out Based on Land Parcel Data. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Dai, X.; Luo, Y. The Effect of Farmland Transfer on Agricultural Green Total Factor Productivity: Evidence from Rural China. Int. J. Environ. Res Public Health 2023, 20, 2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, G.; Liu, X.; Lakshmanna, K. Spatiotemporal Coupling and Driving Factors of Farmland Transfer and Labor Transfer Based on Big Data: The Case of Xinjiang, China. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2022, 2022, 7604448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, B.; Shi, F.; Huang, Y.; Abatechanie, M. The Impact of Agricultural Socialized Services to Promote the Farmland Scale Management Behavior of Smallholder Farmers: Empirical Evidence from the Rice-Growing Region of Southern China. Sustainability 2021, 14, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Chen, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, D.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, M.; Xia, X. Suitability evaluation of large-scale farmland transfer on the Loess Plateau of Northern Shaanxi, China. Land Degrad. Dev. 2019, 30, 1258–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L. Does the confirmation of rural land rights promote the circulation of rural land in China. J. Manag. World 2016, 5, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Cai, D.; Han, K.; Zhou, K. Understanding peasant household’s land transfer decision-making: A perspective of financial literacy. Land Use Policy 2022, 119, 106189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Bai, Y. Knowing and Doing: The Perception of Subsidy Policy and Farmland Transfer. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Gao, Z.; Nian, Y.; Ma, H. Does Social Relation or Economic Interest Affect the Choice Behavior of Land Lease Agreement in China? Evidence from the Largest Wheat−Producing Henan Province. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, C.; Juan, Z.W. Land Transfer Incentive and Welfare Effect Research from Perspective of Farmers’ Behavior. Econ. Res. J. 2015, 50, 163–177. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Wen, F. From Employees to Entrepreneurs: Rural Land Rental Market and the Up grade of Rural Labor Allocation in Non-Agricultural Sectors. J. Manag. World 2020, 36, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Chang, L. Analysis on Basic Characteristics and Regional Differences of the Desire of Peasant Household Land Mobility—Based on a Survey on Three Rural Areas in Guanzhong Region. J. Xi’an Jiaotong Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2015, 35, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Zhang, B.; Xu, Z. The Impact of Credit Availability on Farmer’s Farmland Transfer Behavior—An Empirical Analysis Based on Mediating Effect Model. World Econ. Pap. 2020, 5, 89–104. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, A.; Khan, M.A.; Charfeddine, L.; McMillan, D. Financial development–economic growth nexus in Pakistan: New evidence from the Markov switching model. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2020, 8, 1716446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, R.P.; Arvin, M.B.; Bahmani, S. Are innovation and financial development causative factors in economic growth? Evidence from a panel granger causality test. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2018, 132, 130–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Chen, T.; Song, Y. Coupling Coordination and Interactivity between Farmland Transfer and Rural Financial Development: Evidence from Western China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 17004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Guo, X.; Zhang, X. Digital Financial Inclusion, Land Transfer, and Agricultural Green Total Factor Productivity. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Standard-Setting Bodies and Financial Inclusion: The Evolving Landscape. Available online: https://www.gpfi.org/publications/global-standard-setting-bodies-and-financial-inclusion-evolving-landscape (accessed on 21 December 2023).

- Gao, Q.; Cheng, C.; Sun, G.; Li, J. The Impact of Digital Inclusive Finance on Agricultural Green Total Factor Productivity: Evidence From China. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 10, 905644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Jia, N.; Li, W.; Wu, R. Digital inclusive finance and rural consumption structure–evidence from Peking University digital inclusive financial index and China household finance survey. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2021, 14, 165–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zheng, X.; Yang, L. Does Digital Inclusive Finance Narrow the Urban-Rural Income Gap through Primary Distribution and Redistribution? Sustainability 2022, 14, 2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, N.; Wang, Y. Can Digital Inclusive Finance Narrow the Chinese Urban–Rural Income Gap? The Perspective of the Regional Urban–Rural Income Structure. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, S. Has Digital Financial Inclusion Narrowed the Urban–Rural Income Gap? A Study of the Spatial Influence Mechanism Based on Data from China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Dai, X.; Cheng, Q.; Lin, W. Can Digital Inclusive Finance Promote Food Security? Evidence from China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tianyun, Z. Digital Inclusive Finance, Factor Price and Labor Mobility. Contemp. Econ. Manag. 2022, 44, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, H.; Li, B.; Tang, D.; Xu, H.; Boamah, V. Research on Digital Inclusive Finance Promoting the Integration of Rural Three-Industry. Int. J. Environ. Res Public Health 2022, 19, 3363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Majeed, A.; Khan, M.A.; Sohaib, M.; Shehzad, K. Digital financial inclusion and economic growth: Provincial data analysis of China. China Econ. J. 2021, 14, 291–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Cheng, Q.; Shi, Y. Influence, Mechanism and Heterogeneity Analysis of Digital Inclusive Finance on Farmland Transfer. Econ. Rev. J. 2023, 4, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. Study on the Influence and Mechanism of Digital Inclusive Finance on Rural Land Transfer: Empirical Evidence from CFPS and PKU—DFIIC. Econ. Manag. 2022, 36, 30–40. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, R.; Conway, G. Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: Practical Concepts for the 21st Century; Institute of Development Studies: Brighton, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Lv, X.; Lv, K. The impact of digital finance on the diversification of rural households’ livelihoods. Rural Econ. 2021, 8, 62–71. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, L.; Zhang, M.; Chen, Y. The Relationship between Livelihood Capital, Multi-functional Value Perception of Cultivated Land and Farmers’ Willingness to Land Transfer: A Regional Observations in the Period of Poverty Alleviation and Rural Revitalization. China Land Sci. 2022, 36, 56–65. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Qiao, S.; Jiang, Y. The causal mechanism of farmers’ chemical fertilizer reduction: An empirical perspective from farmland transfer-in and digital extension. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1231574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, B. 40-year reform of farmland institution in China: Target, effort and the future. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2018, 10, 16–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deininger, K.; Feder, G. Land Institutions and Land Markets; Policy Research Working Paper Series; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Tostlebe, A.S. Capital in agriculture: Its formation and financing since 1870. In NBER Books; National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.; Yu, T.; Yu, F. The Impact of Digital Finance on Agricultural Mechanization: Evidence from 1869 Counties in China. Chin. Rural Econ. 2022, 2, 76–93. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L.; Zhu, C. Impact of Digital Inclusive Finance on Rural High-Quality Development: Evidence from China. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2022, 13, 7939103. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhou, M. Does digital inclusive finance promote agricultural production for rural households in China? Research based on the Chinese family database (CFD). China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2021, 13, 475–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Wu, X.; Zhu, J. Digital Finance and Enterprise Technology Innovation: Structural Feature, Mechanism Identification and Effect Difference under Financial Supervision. J. Manag. World 2020, 36, 52–66+59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohansal, M.R.; Ghorbani, M.; Mansoori, H. Effect of Credit Accessibility of Farmers on Agricultural Investment and Investigation of Policy Options in Khorasan-Razavi Province. J. Appl. Sci. 2008, 8, 4455–4459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, Y. How does financial development affect non-agricultural employment—Evidence from national poverty counties during the period of poverty alleviation. Rev. Investig. Stud. 2021, 40, 129–146. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y. Research on the Mechanism of Digital Inclusive Finance Promoting Rural Revitalization and Development. Mod. Econ. Res. 2022, 10, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W. Does Digital Financial Inclusion Improve Farmers’ Access to Credit? J. Huazhong Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2021, 1, 109–119+179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, G.; He, C.; Zhang, X. Can the Development of Digital Inclusive Finance Promote Agricultural Mechanization?—Based on the Perspective of the Development of Agricultural Machinery Outsourcing Service Market. J. Agrotech. Econ. 2022, 1, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhu, G.; Zou, W. Farmers’ Livelihood Capital, Family Factor Flowing and Farmland Transfer Participation. Resour. Environ. Yangtze Basin 2021, 30, 992–1002. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Ma, W.; Mishra, A.K.; Gao, L. Access to credit and farmland rental market participation: Evidence from rural China. China Econ. Rev. 2020, 63, 101523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, L.; Long, Q. Impact of Credit Support on Agricultural Entrepreneurship. J. South China Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2022, 21, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Wang, T.; Zhao, X. Does Digital Inclusive Finance Promote Coastal Rural Entrepreneurship? J. Coast. Res. 2020, 103, 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bing, Z.; Na, L. Research on the Influence of Digital Inclusive Finance on Non-agricultural Transfer of Rural Labor Force—Empirical Analysis Based on Mlogit and Threshold Model. World Agric. 2022, 27, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wu, L.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y. The Impact of Digital Financial Inclusion on Agricultural Green Growth: On the Adjustment Function of Rural Human Capital Investment. Inq. Into Econ. Issues 2022, 165–180. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Yin, H. The impact of financial development on physical capital: A Test and analysis based on Jiangxi data. J. Commer. Econ. 2013, 65–66. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, F.; Li, L.; Song, S.; He, Z.; Deng, W.; Jiang, L. The Impact of Livelihood Capital on Farmers’ Willingness of Forestland Transfer and Circulation. Issues For. Econ. 2022, 42, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, W. Digital Inclusive Finance, Social Networks, and Rural Household Entrepreneurship—Based on the Perspective of Formal and Informal Financial Alternatives. World Agric. 2023, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, X. The Impact of Internet Use on the Decision-making of Farmland Transfer and its Mechanism: Evidence from the CFPS Data. Chin. Rural Econ. 2020, 3, 57–77. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Cai, Z.; Qin, X. Does Internet use help transfer out of agricultural land in the long term? J. Hunan Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2022, 23, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, F.; Zhang, Q.; Huo, X. The Impact of Internet Use on Farmland Transfer of Professional Apple Growers: An Analysis of the Mediation Effect of Information Search, Social Capital and Credit Acquisition. China Land Sci. 2021, 35, 63–71. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Han, J. Study on the influence of internet use on farmer’s land management scale. World Agric. 2021, 11, 17–27+127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Cen, J. How Does Digital Inclusive Finance Affect Regional Digital Transformation? J. Xi’an Univ. Financ. Econ. 2023, 36, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Wu, M.; Zhang, X. Internet, Farmland Circulation and Sustainable Livelihood. RD Manag. 2022, 34, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Wang, A.; Zhu, Z. Digital Empowerment: The Impact of Internet Usage on Farmers’ Credit and Its Heterogeneity. J. Agrotech. Econ. 2022, 324, 82–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Xu, R. The Use of the Internet and the Alleviation of Credit Exclusion Based on the Data from China Family Panel Studies. Wuhan Univ. J. (Philos. Soc. Sci.) 2021, 74, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Luo, B.; Luo, J. Application of Internet Information Technology and Farmer’s Formal Credit Constraint—Taking the Survey Data of 915 Farmer Households in Shanxin as An Example. J. North. AF Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 23, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wei, B.; Su, K. Can internet usage improve the level of credit for farmers—Empirical Research Based on CFPS Panel Data. Econ. Theory Bus. Manag. 2020, 40, 58–72. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison, N.B.; Steinfield, C.; Lampe, C. The Benefits of Facebook “Friends:” Social Capital and College Students’ Use of Online Social Network Sites. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2007, 12, 1143–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, A.; Guo, Y. Internet Use and Residents’ Social Capital: A Study Based on the Data of China Family Panel Studies. Macroeconomics 2021, 21, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainie, L.; Wellman, B. Networked: The New Social Operating System; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.; Chu, Q.; Zhang, T.; Li, Q.; Liu, J.; Yamaka, W. The Structural Causes and Trend Evolution of Imbalance and Insufficiency of Development of Digital Inclusive Finance in China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, M.; Li, W.; Teo, B.S.X.; Othman, J. Can China’s Digital Inclusive Finance Alleviate Rural Poverty? An Empirical Analysis from the Perspective of Regional Economic Development and an Income Gap. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Yu, B.; Yang, X. The Agricultural–Ecological Benefit of Digital Inclusive Finance Development: Evidence from Straw Burning in China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Ning, M.; Yang, C. Evaluation of the Mechanism and Effectiveness of Digital Inclusive Finance to Drive Rural Industry Prosperity. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, F. Rural Livelihood Diversity in Developing Countries: Evidence and Policy Implications; ODI Natural Resources Perspectives; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999; Volume 40. [Google Scholar]

- Ian, S. Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: A Framework for Analysis; IDS Working Paper; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1998; Volume 72. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, S.; Lin, L.; Liu, S.; Wei, Y.; Xu, D.; Li, Q.; Su, S. Interactions between sustainable livelihood of rural household and agricultural land transfer in the mountainous and hilly regions of Sichuan, China. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 27, 725–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Dong, Q.; Rao, X.; Zhao, L. Farm household vulnerability analysis methodology and its localized application. Chin. Rural Econ. 2007, 4, 32–39. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Liu, R.; Xu, Y. Relocation for Poverty Alleviation, Rural households’ Livelihood Capital and Income Inequality—Evidence from the Southern Shanxi Province. J. Agrotech. Econ. 2019, 16, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, K. Measuring Destitution: Integrating Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches in the Analysis of Survey Data; IDS Working Paper; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2003; pp. 217–234. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Mei, Y. Study on the Regional Differences of the Impact of Farmland Transferring on Farmer’s Livelihood Strategies—Analysis of the Mediation Effect Based on Livelihood Capital. For. Econ. 2021, 43, 21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.; Yue, Z. Livelihood Capital, Livelihood Risks and Farmers’ Livelihood Strategies. Issues Agric. Econ. 2012, 33, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Rao, D.; Yang, L.; Min, Q. Subsidy, training or material supply? The impact path of eco-compensation method on farmers’ livelihood assets. J Env. Manag. 2021, 287, 112339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, L.; Zeng, Z.; Sun, J.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, Y. Study on Livelihood Assets-Based Spatial Differentiation of the Income of Natural Tourism Communities. Sustainability 2018, 10, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, X.; Yan, J.; Zhang, Y. Evaluating the role of livelihood assets in suitable livelihood strategies: Protocol for anti-poverty policy in the Eastern Tibetan Plateau, China. Ecol. Indic. 2017, 78, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wu, Y.; Xiao, J.J. The impact of digital finance on household consumption: Evidence from China. Econ. Model. 2020, 86, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falck, O.; Gold, R.; Heblich, S. E-Lections: Voting Behavior and the Internet. Am. Econ. Rev. 2014, 104, 2238–2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivus, O.; Boland, M. The Employment and Wage Impact of Broadband Deployment in Canada. Can. J. Econ./Revue Can. D’économique 2015, 48, 1803–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Tang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, D. The Relief Degree of Land Surface in China and Its Correlation with Population Distribution. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2007, 62, 1073–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peking University Digital Inclusive Finance Index (2011–2020). Available online: https://idf.pku.edu.cn/yjcg/zsbg/513800.htm (accessed on 18 December 2023).

- Instructions for the Use of China Rural Revitalization Survey. Available online: http://rdi.cass.cn/ggl/202210/t20221024_5551642.shtml (accessed on 18 December 2023).

- Su, L.; He, X.; Kong, R. The Impacts of Financial Literacy on Farmers’ Behavior of Farmland Transfer:An Analysis Based on the Regulatory Role of Farmland Certification. Chin. Rural Econ. 2018, 8, 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Wang, J. Nonlinear relationship between municipal solid waste and economic growth. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2022, 32, 63–70. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S. Poor Village Mutual Fund, Formal Finance and Informal Finance: Substitutive or Complementary? Finac. Res. 2018, 5, 120–136. [Google Scholar]

- Firmansyah, E.A.; Masri, M.; Anshari, M.; Besar, M.H.A. Factors Affecting Fintech Adoption: A Systematic Literature Review. FinTech 2022, 2, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çera, G.; Ajaz Khan, K.; Rowland, Z.; Ribeiro, H.N.R. Financial Advice, Literacy, Inclusion and Risk Tolerance: The Moderating Effect of Uncertainty Avoidance. E+M Ekon. A Manag. 2021, 24, 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Obs. | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min. | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DIF | 3165 | 324.4804 | 29.0235 | 292.31 | 387.49 |

| LAND | 3165 | 0.5975 | 0.4905 | 0 | 1 |

| DIE | 3165 | 3.9457 | 1.2139 | 1 | 5 |

| LC | 3165 | 0.2124 | 0.2098 | 0.001 | 0.77 |

| HEA | 3165 | 3.5934 | 0.9974 | 0 | 1 |

| SPE | 3165 | 0.0193 | 0.1375 | 0 | 1 |

| GEN | 3165 | 0.8588 | 0.3483 | 0 | 1 |

| MAR | 3165 | 0.8900 | 0.3129 | 0 | 1 |

| COOP | 3165 | 0.2395 | 0.4268 | 0 | 1 |

| MEM | 3165 | 4.0884 | 1.5900 | 1 | 10 |

| RDLS | 3165 | 0.5144 | 0.4999 | 0 | 1 |

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DIF | 0.0083 *** | 0.0083 *** | 0.0085 *** | 0.0078 *** | 0.0085 *** | 0.0084 *** | 0.0086 *** |

| Hea | −0.0005 | −0.0015 | −0.0035 | −0.0010 | −0.0052 | −0.0055 | |

| Spe | 0.7976 *** | 0.7872 *** | 0.6779 *** | 0.6703 *** | 0.6744 *** | ||

| Gen | 0.3146 *** | 0.3703 *** | 0.3739 *** | 0.3803 *** | |||

| Mar | −0.2812 *** | −0.3057 *** | −0.2706 *** | ||||

| Coop | 0.3041 *** | 0.3080 *** | |||||

| Mem | −0.0414 *** | ||||||

| Cons | −2.4424 *** | −2.4408 *** | −2.4988 *** | −2.5545 *** | −2.5820 *** | −2.5914 *** | −2.5190 *** |

| N | 3165 | 3165 | 3165 | 3165 | 3165 | 3165 | 3165 |

| R2 | 0.0244 | 0.0244 | 0.0291 | 0.0344 | 0.0374 | 0.0445 | 0.0464 |

| Explained Variable | LAND | LAND |

|---|---|---|

| Test Method | Variable Logarithmic Treatment (1) | Replace Estimation Method (2) |

| LnDIF | 2.7810 *** (9.51) | |

| DIF | 0.0139 *** (9.59) | |

| Cons | −15.7870 (−9.48) | −4.0452 *** (−8.67) |

| Control | Yes | Yes |

| N | 3165 | 3165 |

| Estimation Method | Two-Stage Least Squares | |

|---|---|---|

| First Stage | Second Stage | |

| DIF | 0.0263 *** (7.57) | |

| RDLS | 8.4060 *** (8.39) | |

| Cons | 287.8148 (105.63) | −7.2552 *** (−7.06) |

| Control | Yes | Yes |

| N | 3165 | 3165 |

| R2 | 0.0981 | 0.0961 |

| F | 70.4384 | |

| Variable | DIE | LC | LAND |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| DIF | 0.0037 *** (4.96) | 0.0025 *** (20.44) | 0.0025 *** (7.71) |

| DIE | 0.0100 *** (3.45) | 0.0141 ** (2.00) | |

| LC | 0.1165 *** (2.67) | ||

| Control | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Cons | 2.8774 *** (11.38) | −0.5921 *** (−14.10) | −0.3438 *** (−3.27) |

| N | 3165 | 3165 | 3165 |

| Mediating Effect Type | Mediating Channel | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|

| Independent Mediating Effect 1 | DIF→DIE→LAND | 0.0029 *** |

| Independent Mediating Effect 2 | DIF→LC→LAND | 0.0027 *** |

| Chain Mediating Effect | DIF→DIE→LC→LAND | 0.0020 *** |

| Variable | Economically Developed Regions | Economically Underdeveloped Regions |

|---|---|---|

| DIF | 0.1161 *** (8.66) | −0.0052 * (−1.65) |

| Control | Yes | Yes |

| N | 1901 | 1264 |

| R2 | 0.0511 | 0.0563 |

| Mediating Effect Type | Mediating Channel | Effect Size | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Economically Developed Regions | Economically Underdeveloped Regions | ||

| Independent Mediating Effect 1 | DIF→DIE→LAND | 0.0036 *** | −0.0019 *** |

| Independent Mediating Effect 2 | DIF→LC→LAND | 0.0032 *** | −0.0018 |

| Chain Mediating Effect | DIF→DIE→LC→LAND | 0.0003 * | −0.0053 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, Z.; Niu, H.; Wei, Y.; Wu, Y.; Yu, Y. Impact and Mechanisms of Digital Inclusive Finance in Relation to Farmland Transfer: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 408. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010408

Xu Z, Niu H, Wei Y, Wu Y, Yu Y. Impact and Mechanisms of Digital Inclusive Finance in Relation to Farmland Transfer: Evidence from China. Sustainability. 2024; 16(1):408. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010408

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Ziqin, Hui Niu, Yuxuan Wei, Yiping Wu, and Yang Yu. 2024. "Impact and Mechanisms of Digital Inclusive Finance in Relation to Farmland Transfer: Evidence from China" Sustainability 16, no. 1: 408. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010408