Abstract

Innovation is critical for organizations seeking to build and maintain a sustainable advantage in the competitive market. This study aims to construct a moderated mediation model to examine the effects of incremental and radical innovations on competitive advantage, which considers the mediating role of innovation speed and the moderating role of a supportive culture. Data from 201 Chinese firms were collected through questionnaires and the research hypotheses were tested using multiple regression analysis and bootstrapping techniques. The empirical results show that incremental and radical innovations have a significant positive effect on competitive advantage. Radical innovation has a greater impact on competitive advantage compared to incremental innovation. Innovation speed mediates the relationship between incremental and radical innovations and competitive advantage. Supportive culture positively moderates the relationship between incremental and radical innovations and innovation speed. Moreover, supportive culture positively moderates the conditional indirect effect of incremental and radical innovation on competitive advantage through innovation speed. Theoretical and practical implications are further discussed.

1. Introduction

Innovation is an important cornerstone of China’s digital economic transformation and is the primary driver of national economic growth. With an increasingly fierce global competitive environment, innovation is vital for enterprises to improve their competitiveness and maintain sustainable competitive advantages [1,2,3]. Previous studies have reported mixed evidence on the relationship between innovation and competitive advantage. Some studies have shown that innovation has a positive impact on competitive advantage [3,4,5,6,7,8], while other studies have found that innovation has a low or negative impact on competitive advantage [9]. One possible reason for this mixed result might be the differences in the type of innovation. As research by Lee et al. [10] suggested, only focusing on a single type of innovation may hinder the potential advantages that come from diversifying innovations.

Incremental and radical innovations, which are categorized according to the degree of novelty of the innovation [11,12,13,14], have attracted the attention of academics and practitioners [15,16]. Radical innovations reflect a high degree of novelty, yet incremental innovations exhibit a lower degree of novelty [17,18,19]. Incremental innovation involves slight improvements to existing technologies, products, and services that can increase a company’s market share, improve competitiveness, and strengthen its market position [20,21,22]. Radical innovation involves developing new technologies, products, or services and making existing ones obsolete, completely changing the competitive landscape and creating new business prospects [19,23,24]. It is generally recognized that incremental and radical innovations are crucial for the long-term survival and growth of a firm.

Although the current literature implicitly assumes that incremental innovation and radical innovation are necessary to improve a firm’s competitive advantage [16,22,25,26], research on how incremental innovation and radical innovation impact a firm’s competitive advantage remains limited. Previous studies have explored the impact of different types of innovations on firms’ competitive advantage, such as market innovation [8], product and process innovations [27], open innovation [28], ambidextrous innovation [29], and collaborative dual innovation [6]. However, there is still a lack of rigorous empirical support for the impact of incremental and radical innovations on competitive advantage. Also, there is still no empirical evidence to suggest which type of innovation has a greater impact on competitive advantage.

Additionally, prior studies suggested that innovation speed is closely related to radical and incremental innovation [30,31,32]. Moreover, most studies have shown that accelerating innovation speed improves innovation efficiency, reduces research and development costs, sets industry standards, enhances product competitiveness, and increases market share and margins [33,34]. Innovation speed is necessary for businesses to gain a competitive advantage [35,36]. Previous research has indicated that innovation speed plays a key mediating role between innovation and competitive advantage [37,38]. However, there are fewer empirical studies on the mediating role of innovation speed in radical and incremental innovation affecting competitive advantage relationships.

Furthermore, cultural context could have an impact on the relationship between innovation and firm performance [2,39]. Several studies have suggested that organizational culture plays an important role in organizational innovation [40,41], such as competing value framework [40,41] and organizational learning culture [42]. Supportive culture has been regarded as one of the organizational cultures conducive to innovation [43,44], which represents mutual learning and knowledge sharing, friendly communication and collaboration, trust, and an encouraging work environment. Supportive culture can motivate employees to work more efficiently and effectively in the organization [45,46,47]. In addition, some studies have shown that organizational culture influences incremental and radical innovation [48,49]. However, there is still no empirical support for supportive culture as a boundary condition for the relationship between incremental and radical innovation and competitive advantage.

Given the above, this study developed a moderated mediation model to close these research gaps. First, we examine the impact of incremental and radical innovations on competitive advantage to understand which types of innovation contribute more to a firm’s competitive advantage. Second, we explore the mediating role of innovation speed to understand the paths through which the two types of innovations affect firms’ competitive advantage. Third, we analyze the moderating role of a supportive culture to reveal how a supportive work environment enhances the impact of different types of innovations on competitive advantage. By examining this relationship and thus providing valuable insight into their interactions. Our findings provide useful references for corporate innovation practice and enrich the theoretical knowledge system of innovation management.

2. Theory and Hypotheses

2.1. The Relationship between Incremental and Radical Innovation and Competitive Advantage

Incremental innovation, which still dominates most industries, relies on a firm’s existing structures and processes and involves small but significant improvements to products and processes [50]. Herbig et al. [51] described three types of incremental innovation—continuous, modified, and process innovations. Incremental innovation refers to refining the existing technological trajectory and making minor improvements to enhance the existing technology [12]. Although incremental innovations involve relatively small technological changes in each unit, their cumulative effect often exceeds that of the original innovation [52,53]. Incremental innovation increases a firm’s competitive advantage by making its product more novel, valuable, and reliable, while better meeting the market demands and promoting consumer loyalty and brand credibility [19,25].

In addition, incremental innovation does not require costly and complicated technology, which effectively reduces the risk of business innovation and enables firms to provide products and services at more competitive prices to gain a competitive advantage [54]. Previous studies have shown that incremental innovation leverages and develops the firms’ prior technological capabilities, which positively affects new product development performance [55], business performance [56], and financial performance [57]. On the one hand, as argued by Banbury and Mitchell [20], the higher the number of industry incumbents to first introduce major incremental product innovations, the greater the market share and the more advantageous it is. Huvaj and Johnson [58] found that complex firms are more inclined to pursue incremental innovation, given their monitorable R&D investment as well as predictable benefits. On the other hand, to enhance their competitive advantage in an intensely competitive environment, SMEs may engage in incremental innovation activities such as launching new differentiated products, extending their product lines, developing new market segments, and creating new distribution formats [21,22]. In summary, incremental innovation helps established firms deal with competitive pressures [53] and creates a competitive opportunity window for SMEs [59].

Radical innovations are higher-order innovations compared to incremental innovations and involve a fundamental change to a technology or product [60]. Radical innovations are adoptable innovations and must be novel, unique, and have a significant impact on future technologies [61]. Previous research has shown that large companies choose to introduce radical product innovations due to economies of scale and scope, even though they require costly resources and a tolerance for failure [12,62]. Radical innovations can have a significant impact not only on a firm’s market share, but also on its financial performance [57], which can enhance or reshape a firm’s competitive advantage [63].

Radical innovation has a long-term and significant impact on a company’s competitive advantage. First, radical innovation is a key engine of growth for firms [64], which helps firms develop unique products, establish industry standards or dominant designs, and provide a first-mover advantage, which allows firms to dominate in a competitive marketplace [31,65]. Second, radical innovation allows firms to avoid the capability trap of incremental innovation and is essential for firms to remain competitive in the long term [66]. Slater and Mohr et al. [67] identified radical product innovation capability as a dynamic capability that delivers superior organizational performance by creating new businesses that enable new product development and commercialization, providing unprecedented customer benefits [68]. Third, radical innovation establishes a new industry by enabling the development of new technologies and products that meet potentially unique customer and market needs [69], creating new market opportunities and reshaping the existing competitive landscape [23,24]. In conclusion, despite the high-risk nature of radical innovation, radical innovation leads to disruptive change that can help firms achieve a temporary profit monopoly and a sustainable competitive advantage in the marketplace [16,26].

Based on the above considerations, we hypothesize the following:

H1a.

Incremental innovation has a positive impact on competitive advantage.

H1b.

Radical innovation has a positive impact on competitive advantage.

2.2. The Mediating Role of Innovation Speed

In a highly competitive business environment, a company must continue to innovate rapidly to meet fast-changing customer needs. In this context, the speed of innovation has been a major focus for companies and scholars. Previous studies use different terminology to describe the speed of innovation, including innovation speed [70], speed-to-market [71], new product development speed [34], etc. Collectively, these studies show that innovation speed represents the time from the initial product concept to the ultimate commercialization of a new product.

Innovation speed plays an important role in creating and sustaining competitive advantage. First, innovation speed has a positive impact on new product success [35]. Several studies have shown that faster innovation speed reduces costs and delivers higher product quality with superior customer benefits to maximize product advantage [36,71]. Second, innovation speed favors the profitability and brand image of the company [34]. By shortening the product development cycle and bringing new products to market faster, to meet consumer demand, the company can enhance its reputation in the consumer market and improve its brand image. Third, innovation speed results in superior performance [72]. Companies that are the first to bring new products to the market can be very profitable [30,71]. In short, innovation speed is positively associated with firms’ competitive advantage.

We further argue that innovation speed mediates the effects of incremental and radical innovation on competitive advantage. On the one hand, incremental innovation is positively related to innovation speed. First, incremental innovation uses existing technology, knowledge, and experience to make small improvements and optimizations to known new product development projects based on previously collected customer feedback [71], thus increasing innovation speed. Specifically, companies can iterate innovative products in a short period through testing and improvement [32]. Second, incremental innovation is about the accumulation of knowledge and experience [73]. Companies can accelerate innovation by incorporating the knowledge and experience of incremental innovation into later innovation processes.

On the other hand, radical innovation is positively related to innovation speed. First, radical innovation creates a first-mover advantage by creating entirely new technologies or products and establishing the industry’s dominant design and technology standards [31]. Introducing new and innovative products to the market can be highly profitable before competitors [30]. Second, radical innovation products achieve the first commercialization to drive innovation speed in new industries [12]. Lee [74] indicated that the greater the degree of radicalization of innovation, the greater the degree of diffusion within the industry and the faster the innovation speed.

We thus hypothesize the following:

H2a.

Innovation speed mediates the relationship between incremental innovation and competitive advantage.

H2b.

Innovation speed mediates the relationship between radical innovation and competitive advantage.

2.3. The Moderating Role of Supportive Culture

Definitions of organizational culture vary, but it is widely recognized that organizational culture is the specific values and beliefs rooted within an organization that provide norms of behavior and guide the activities and actions of the organization [75]. Based on the resource-based view, as an important intangible resource, organizational culture can bring sustainable competitive advantage to an enterprise [76]. As an essential organizational culture, a supportive culture represents a trusting, encouraging, open, collaborative, and relationship-oriented work environment that benefits a company’s long-term innovative performance in a dynamic environment [77]. Supportive cultures promote the acceptance of innovative concepts by employees and the initiation of innovations, as well as the fact that employees are better equipped to support one another and collaborate with others [44]. Accordingly, this study suggests that supportive cultures may moderate the effects of incremental and radical innovation on innovation speed, as demonstrated by the following points:

First, incremental innovation improves existing products by enhancing existing knowledge [64]. A supportive culture encourages employees to communicate and collaborate, promoting the sharing of knowledge and experience [45], which strongly supports incremental innovation and accelerates its pace. Furthermore, radical innovation emphasizes the reforming of mainstream knowledge to eliminate obsolete knowledge and generate new knowledge to innovate [73]. Employee tacit knowledge sharing, transformation, and application enable companies to achieve radical innovation breakthroughs [78], significantly accelerating the pace of innovation.

Second, supportive culture reflects a trusting, safe, and collaborative working environment that increases employee commitment and job satisfaction [79,80], encourages collaborative problem-solving among employees, and facilitates quality improvement practices in the organization [81]. An organizational environment in which firms provide encouragement and rewards can increase employees’ psychological safety to promote incremental and radical innovation [82,83].

Third, supportive culture is a decentralized organizational structure that encourages employees to participate in decision-making and management, to stimulate their potential, and to satisfy their need for self-actualization [84]. Dewar and Dutton [14] showed that decentralization facilitates firms to engage in incremental innovations, while Huvaj and Johnson [58] indicated that firms with a complex organizational structure will produce fewer radical innovations, but will produce more incremental innovations. In this context, incremental and radical innovations are implemented more efficiently and rapidly. Having considered the above, we propose the following hypotheses:

H3a.

Supportive culture positively moderates the relationship between incremental innovation and innovation speed.

H3b.

Supportive culture positively moderates the relationship between radical innovation and innovation speed.

Furthermore, as previously stated, both incremental and radical innovation can improve competitive advantage by increasing innovation speed. In addition, a supportive culture can positively moderate the relationship between incremental and radical innovation and innovation speed. Thus, given the above prediction that supportive culture plays a moderating role in the theoretical model of incremental and radical innovation–innovation speed–competitive advantage, supportive culture will moderate the indirect effect of innovative capability on competitive advantage through innovation speed. Accordingly, we hypothesize the following:

H4a.

Supportive culture positively moderates the mediating role of innovation speed between incremental innovation and competitive advantage.

H4b.

Supportive culture positively moderates the mediating role of innovation speed between radical innovation and competitive advantage.

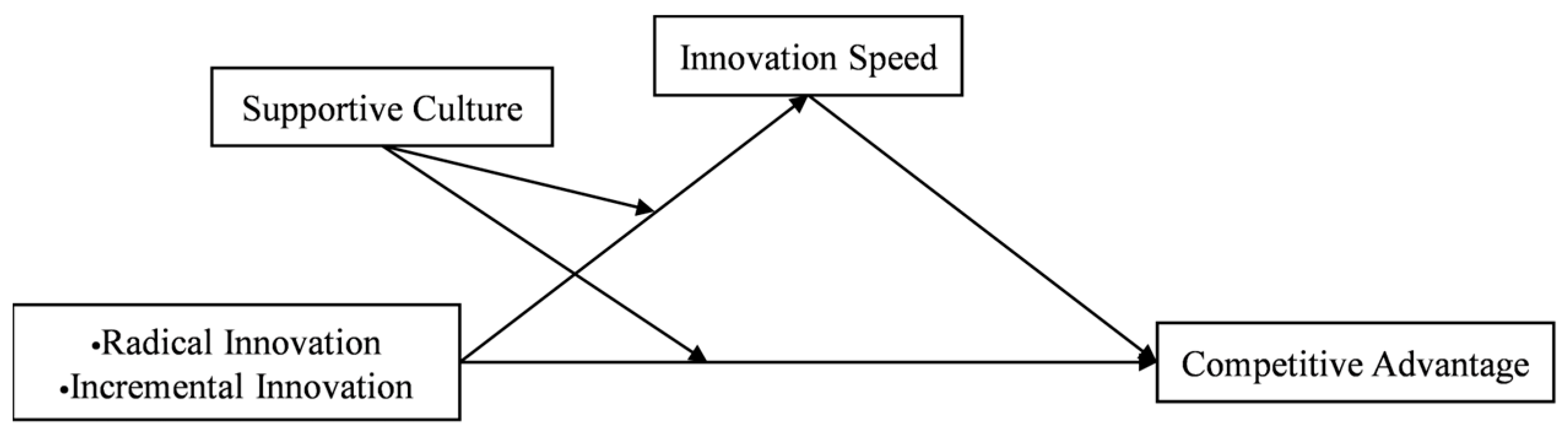

The research model of this paper is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research model.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

This study identified questionnaire items based on previous research; the original questionnaire was developed using translation and back-translation methods. To ensure readability, comprehensibility, and reliability, the questionnaire was revised and improved by integrating the suggestions of academic experts in the field of innovation management and the pre-survey feedback from 10 business managers.

Given the generalizability of the study and to ensure the return rate of the questionnaire, the respondents of this study are set to be business managers in various industries in the Yangtze River Delta region of China, which has a high level of innovation activity. This study distributed 300 questionnaires to collect data by sending online questionnaires to “acquaintances”, university MBA students, and enterprise managers of science and technology parks; the respondents were middle-level or senior-level managers. All questionnaires are anonymous and adopt the avoidance principle. After discarding invalid samples such as missing data and other irregular unanswered questions from the 230 questionnaires received, 201 valid samples were retained, giving a sample recovery rate of 67%. Firms in the sample are mainly located in the more innovative regions of China (90.55%), such as Beijing, Shanghai, Hangzhou, and so on. In total, 73.13% of the firms are small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which are mainly concentrated in traditional manufacturing (28.36%) and high-tech industries (42.29%). Overall, the sample comparison met the requirements of this study.

3.2. Measures

We searched the Web of Science database using incremental innovation, radical innovation, and competitive advantage as topic keywords and focused mainly on peer-reviewed journal articles; we excluded articles that did not fit the research theme, obtaining 395 articles. We relied on recent reviews [2,85] as well as our literature review to identify relevant variables for this study.

All measurement scales were used from previous studies and were then modified to ensure content validity and facilitate data collection and analysis. We employed a seven-point Likert-type scale (from strongly disagree to strongly agree) to assess the innovation capability and supportive culture variables. Next, we used a five-point Likert-type scale (from strongly disagree to strongly agree) to measure the variables of innovation speed and competitive advantage.

The dependent variable is competitive advantage. To investigate the new product innovation performance of the company, we adapted items from a study by Carbonell et al. [86]. The sample items include five questions, as follows: a new product or service gives us an important competitive advantage; product/service experience was superior to competitors; customer solution was superior to competitors; increased brand awareness; and satisfaction with new products.

The independent variable is incremental innovation and radical innovation. Items were proposed by Subramaniam and Youndt [73]. The measure of incremental innovation has three questions, as follows: innovations that reinforce your prevailing product/service lines; reinforce your existing expertise in prevailing products/services; and reinforce how you currently compete. Radical innovation was measured using three questions including the following: innovations that make your prevailing product/service lines obsolete; make your existing product/service lines obsolete; and fundamentally change your prevailing products/services.

The mediator is innovation speed. Items proposed by Carbonell et al. [86] were used to investigate the new product speed of commercialization. The sample items include three questions, as follows: developed and launched faster than major competitors; completed in less time than what was considered normal for the industry; and launched ahead of the original schedule that was developed.

The moderator is supportive culture. Items were proposed by Wallach [77] and formed a supportive culture [43]. These indicators contain two aspects—relationship and environment. The items include the following: relationship-oriented; employees trust each other; employees are collaborative and encourage new things; and an equitable and open working climate.

Control variables. Based on the previous literature [58], we considered firm age, firm size, and R&D intensity as the control variables. Firm age was measured using the natural logarithm of the years of company establishment and we used the number of employees to measure firm size with five ordinal categorical variables. R&D intensity [83] refers to the investment in the company’s new product, including R&D personnel (the percentage of all employees) and R&D expenditure (the percentage of total revenues).

3.3. Common Method Biases

Common method biases (CMB) are widely present in questionnaire methods. It is a variation derived from measurement methods rather than research constructs, common method variance due to common sources or raters, item characteristics, item context, and measurement context. Common method bias has potentially serious effects on research findings [87]. Therefore, this study uses Harman’s single-factor test method to test the common method bias problem, which involves conducting exploratory factor analysis on all items of the questionnaire and examining the unrotated first-factor solution. The first principal component in the total explained variance is 28.62% less than the threshold value of 40%. Therefore, there is no serious common method bias issue in the study’s data set.

3.4. Analytical Method

In this study, we used SPSS 26.0 and AMOS 26.0 software to analyze the sample data. First, we reported the reliability and validity, descriptive statistics, and correlation of measurement; construct validity was assessed using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Second, according to the method proposed by Baron and Kenny [88], we tested the hypothesis through regression analysis. Finally, we tested the moderated mediating effect using the SPSS macro-PROCESS, as suggested by Hayes [89].

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Reliability and Validity

To test the construct validity of our measurement, we used AMOS 26.0 for confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). We evaluated measurement models that included all five latent variables and showed that the measurement models fit the data well, with χ2/df = 1.977 (less than 2), p < 0.0001, RMSEA = 0.07 (less than 0.08), SRMR = 0.045 (less than 0.05), CFI = 0.958, NFI = 0.919, RFI = 0.901, and TLI = 0.948 (all greater than 0.9) [90]. All fit indices have reached the ideal level, demonstrating that the construct validity is satisfactory. Table 1 shows the measurement items, factor loading, Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability (CR), and the average variance extracted (AVE).

Table 1.

Reliability and validity analysis.

The reliability of the measures is assessed using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient and CR, which must exceed the recommended value of 0.7 [91]. Cronbach’s alpha values ranged from 0.866 to 0.925 and CR values ranged from 0.868 to 0.923, all above 0.7, showing good internal consistency and reliability.

Convergent validity was assessed considering factor loading and AVE, which should exceed the 0.5 threshold. Each item’s standardized factor loading ranged from 0.766 to 0.936, and the AVE ranged from 0.659 to 0.773, indicating a high degree of convergent validity.

To assess discriminant validity, the square roots of the AVE of a construct should exceed the correlation coefficients between that construct and the other constructs in the model [91]. The results shown in Table 2 suggest that the square roots of all constructs had AVE values ranging from 0.812 to 0.879, all of which are larger than the correlation coefficients between constructs in the model, indicating a good discriminant validity in this measurement model. Overall, we can conclude that the model has sufficient reliability and validity.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and correlation matrix.

4.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

Table 2 displays variable means, standard deviations, and Pearson correlations. The variables’ correlation coefficients are less than 0.8, which means the study satisfies the statistical criteria. The results show that incremental innovation (β = 0.522, p < 0.01), radical innovation (β = 0.519, p < 0.01), supportive culture (β = 0.527, p < 0.01), and innovation speed (β = 0.744, p < 0.01) are statistically significantly correlated with competitive advantage. In addition, control variables other than age and scale, such as R&D personnel (β = 0.285, p < 0.01) and R&D expenditure (β = 0.274, p < 0.01), also show a statistically significant correlation with competitive advantage. Overall, these results provide preliminary support for our hypothesis. In addition, we calculate the value of the variance inflation factor (VIF) of each model to assess multicollinearity. The VIF value of each model is well below 10, indicating that there is no serious collinearity problem. At the same time, to avoid the interference of collinearity, we perform multiple regression analysis with all latent variables being mean-centered [92].

4.3. Hypotheses Testing

To test mediating effects, we employed the hierarchical multiple regression method; for testing the moderated mediating effect, we used the bootstrap technique. Table 3 presents the results of the regression analysis. In terms of control variables, the results in model 1 and model 3, except for firm age and scale, R&D personnel (β = 0.156, p < 0.05), and R&D expenditure (β = 0.236, p < 0.01), are statistically significant and positive on innovation speed. Otherwise, R&D personnel (β = 0.194, p < 0.05) is statistically significant and positive on competitive advantage.

Table 3.

Results of regression analyses on mediating effects.

4.3.1. Direct Effect Analysis

As shown in Table 3, the coefficients for incremental innovation (β = 0.300, p < 0.001) and radical innovation (β = 0.305, p < 0.001) in model 2 are significant and positive on competitive advantage. Thus, H1a and H1b are supported.

4.3.2. Mediating Effect Analysis

Baron and Kenny [88] suggest testing the mediation. First, the independent variable has a significant impact on the dependent variable. According to model 2, the estimated coefficient of incremental and radical innovation has a positive and statistically significant effect on competitive advantage. Second, the independent variable must be significantly correlated with the mediating variable. Model 4 indicates that incremental innovation (β = 0.195, p < 0.01) and radical innovation (β = 0.388, p < 0.001) on innovation speed is positive and statistically significant. Third, the mediating variable must be significantly associated with the dependent variable. Model 5 indicates that innovation speed (β = 0.622, p < 0.001) has a significant impact on competitive advantage. Fourth, once the mediating variable has been included in the model, a significant independent variable suggests that the mediating variable only plays a partial mediating role; a non-significant independent variable suggests that the mediating variable plays a complete mediating role. In model 5, the coefficient for incremental innovation is significant and decreased from 0.300 to 0.178 (p < 0.01). However, the coefficient for radical innovation is not significant and decreased from 0.305 to 0.063 (p < 0.1). From the above four-step regression analysis results, we can suggest that innovation speed partially mediates incremental innovation and competitive advantage, while innovation speed completely mediates radical innovation and competitive advantage. Thus, H2a and H2b are supported.

Additionally, we perform a bootstrap analysis (a bootstrap sample of 5000 cases with a 95% confidential interval (CI)) using the PROCESS software to further test the robustness of the mediation effect. When the 95% confidence interval (CI) does not include zero, it is inferred that the mediating effect is significant; otherwise, the mediation effect is not supported [89]. We adopted Model 4 to test the mediation effects. Regarding the mediator of innovation speed, the results are displayed in Table 4. The indirect effect of incremental innovation on competitive advantage through innovation speed was statistically significant (indirect effect = 0.176, SE = 0.033, 95% CI [0.114, 0.242]). The indirect effect of radical innovation on competitive advantage through innovation speed was statistically significant (indirect effect = 0.189, SE = 0.029, 95% CI [0.138, 0.250]). None of the 95% confidence intervals include zero. Considering the above studies, we can conclude that innovation speed plays a mediating role between incremental and radical innovation and competitive advantage. Thus, hypotheses H2a and H2b are confirmed.

Table 4.

Mediation effect bootstrap test.

4.3.3. Moderated Mediating Effect Analysis

Following the suggestions of previous studies [89], we utilized the PROCESS procedure developed by Hayes, based on 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals, constructed through 5000 bootstrapped samples to test the moderated mediation effects. PROCESS is an observed variable OLS and logistic regression path analysis modeling tool. We estimate direct and indirect effects by relying on the principles of ordinary least squares regression, as well as detecting simple slopes and regions of significance for interaction and conditional indirect effects in the moderated mediation model by calculating bootstrap confidence intervals. We adopted PROCESS Model 7 to test the moderated mediation effects. The results are illustrated in Table 5 and Table 6.

Table 5.

Results for moderated mediation model with incremental innovation.

Table 6.

Results for moderated mediation model with radical innovation.

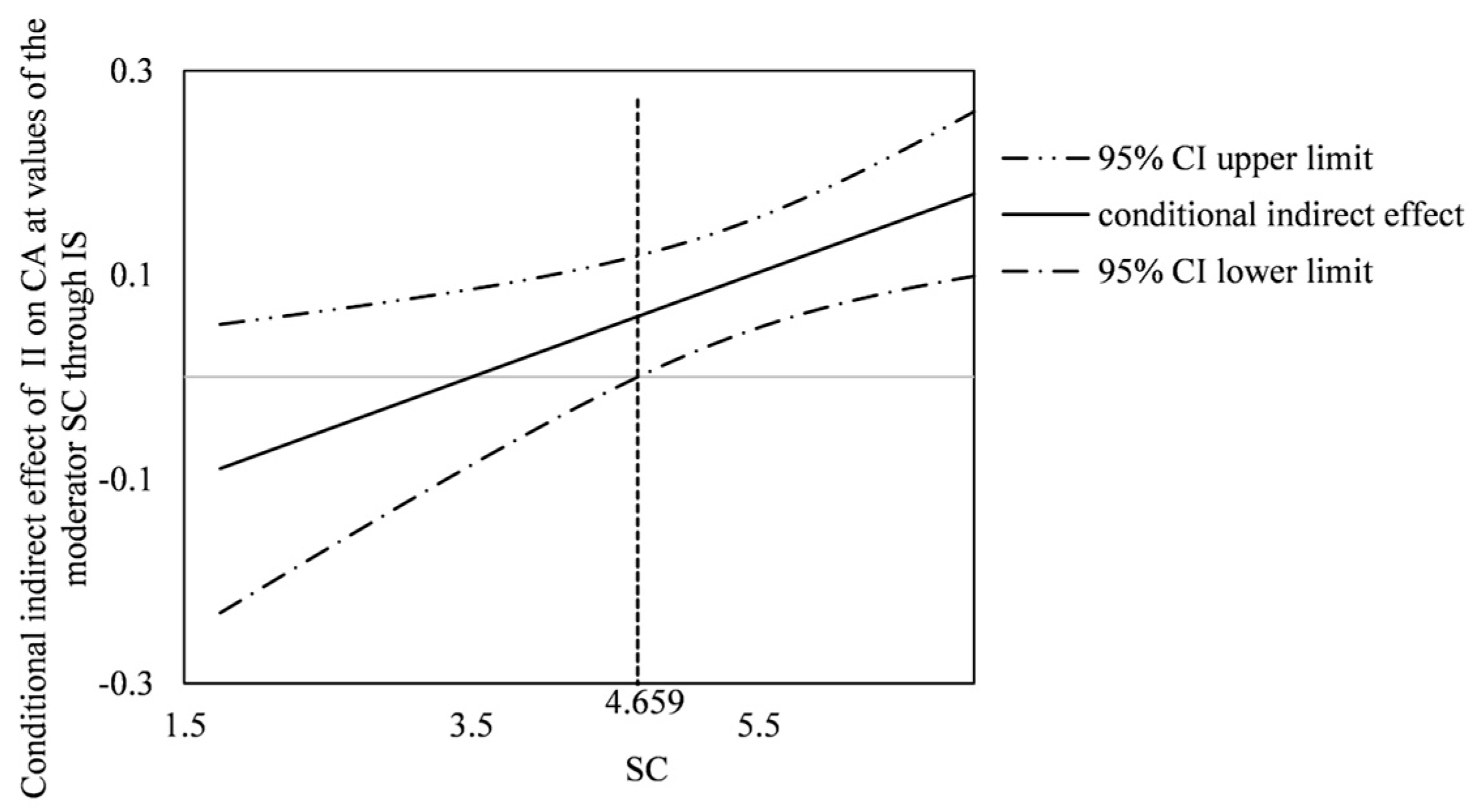

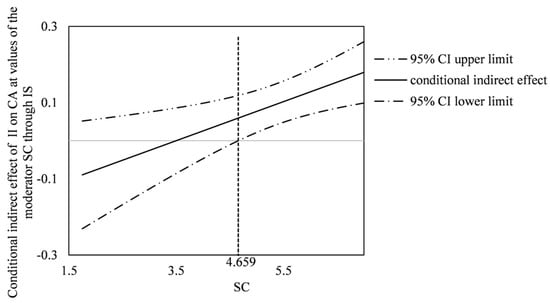

We first examined the moderated mediation model with incremental innovation as the independent variable. As shown in Table 5, the effect of incremental innovation on innovation speed is significant and positive (b = 0.199, SE = 0.055, 95% CI [0.090, 0.307]); the interaction terms incremental innovation and supportive culture are significant and positive (b = 0.102, p < 0.05, 95% CI [0.029, 0.175]). Thus, H3a was supported. Notably, the index of moderated mediation (IMM) is also significant (IMM = 0.061, SE = 0.023, 95% CI [0.021, 0.109]), which is a direct quantification of the linear form of the association between indirect effects and moderators [93]. As the confidence interval (CI) does not include zero and the index is positive, we infer that the conditional indirect effect of incremental innovation on competitive advantage through innovation speed is positively moderated by supportive culture, indicating that as supportive culture increased, the positive effect of incremental innovation on competitive advantage through innovation speed would be enhanced. Therefore, H4a was supported.

To better clarify the interactions, we used the Johnson–Neyman technique [89] to calculate the regions of significance to provide a simple slope test for the moderated relationship. The significance region is described as the point at which the confidence interval is wholly above or below 0. As illustrated in Figure 2, regions of significance showed that, for non-centered 7-point supportive culture values above 4.659, 77.61% of cases fall within the significance regions. These results indicate that the indirect positive relation between incremental innovation and competitive advantage through innovation speed becomes significant. This provides support for H4a.

Figure 2.

Conditional indirect effect of incremental innovation on competitive advantage at values of the moderator supportive culture through the mediator innovation speed.

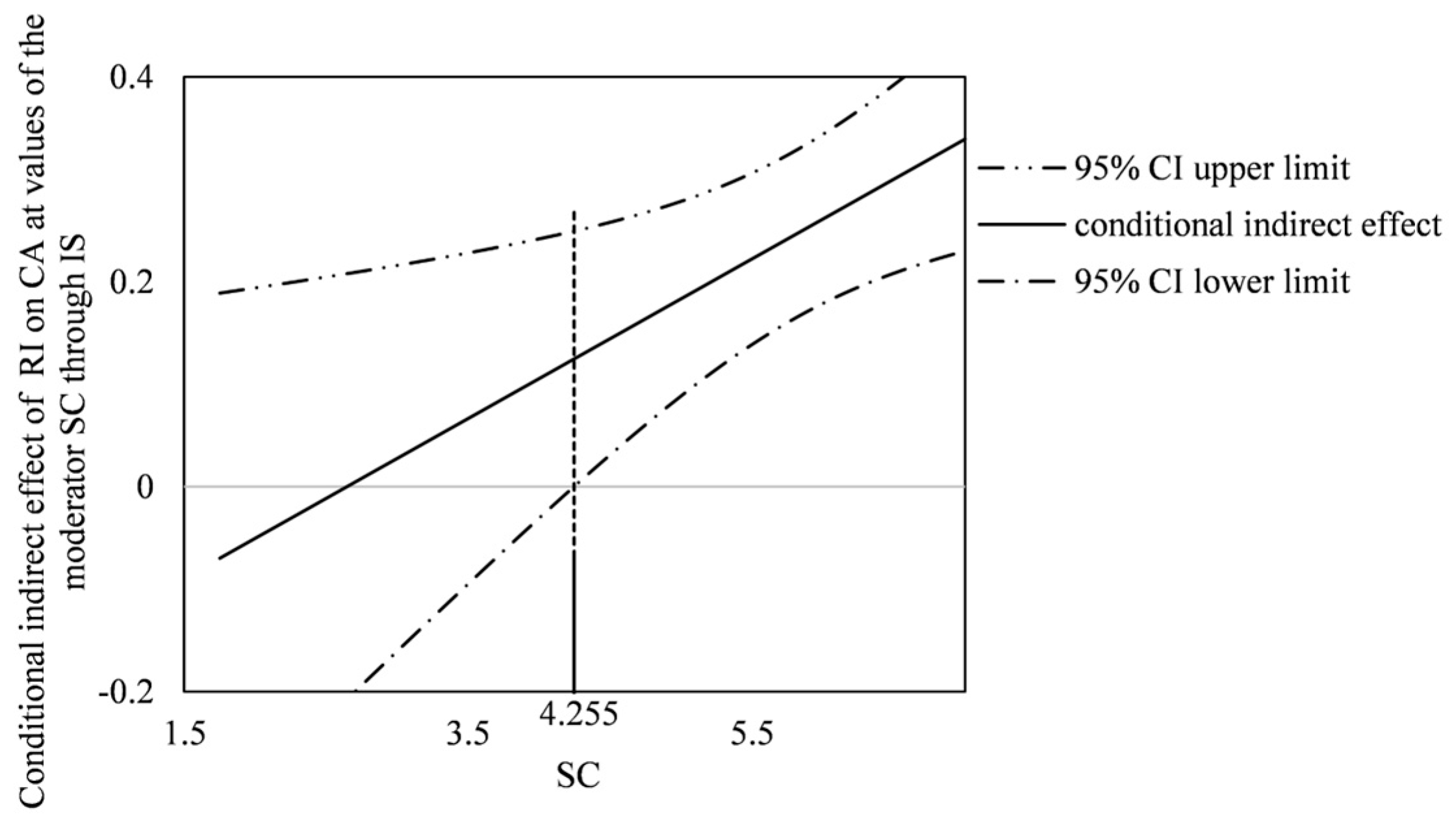

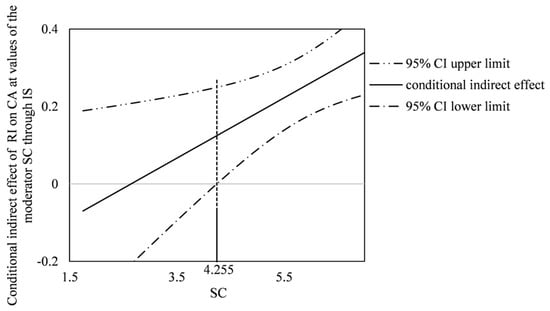

We next examined the moderated mediation model with radical innovation as the independent variable. As shown in Table 6, the interaction terms radical innovation and supportive culture are significantly related to innovation speed, b = 0.078, SE = 0.031, 95% CI [0.017, 0.139]; the confidence interval for the regression coefficient of the product of radical innovation and supportive culture does not include zero. Thus, H3b was supported. The index of moderated mediation (IMM) is significant and positive (IMM = 0.047, SE = 0.018, 95% CI [0.017, 0.086]), the confidence interval does not include zero, and the upper bound is positive. Therefore, we infer that the conditional indirect effect of radical innovation on competitive advantage through innovation speed is positively moderated by supportive culture, indicating that as supportive culture increases, the positive effect of radical innovation on competitive advantage through innovation speed would be enhanced. Therefore, H4b was supported.

Using the Johnson–Neyman technique to discern the nature of the significant interaction, the regions of significance showed that (see Figure 3), for non-centered 7-point supportive culture values above 4.255, 85.07% of cases fall within the significance regions. These results indicate that the indirect positive relation between radical innovation and competitive advantage through innovation speed becomes significant. This provides support for H4b.

Figure 3.

Conditional indirect effect of radical innovation on competitive advantage at values of the moderator supportive culture through the mediator innovation speed.

5. Discussion

This study analyses the intrinsic mechanisms and boundary conditions of incremental and radical innovation on competitive advantage, to explore how firms can enhance their competitive advantage in a dynamic environment. Based on the empirical analysis of survey data from 201 Chinese firms, we find that incremental and radical innovations enhance firms’ competitive advantage and that innovation speed mediates the relationship between incremental and radical innovations and competitive advantage. Meanwhile, a supportive culture reinforces the positive impact of incremental and radical innovation on innovation speed. Furthermore, we constructed a moderated mediate model to explore a conditional indirect effect. The results show that a higher level of supportive culture strengthens the mediating effect of innovation speed on the relationship between incremental and radical innovation and competitive advantage. Table 7 shows the statistical results of all the hypotheses tests. Theoretical contributions, practical implications, limitations, and future research are discussed below.

Table 7.

Statistical results of hypotheses.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

This study makes several theoretical contributions. First, this study provides rigorous direct empirical support for the view that incremental and radical innovations contribute to competitive advantage. Although the relationship between incremental and radical innovation and competitive advantage is well supported from various perspectives (e.g., financial performance [57], business performance [56], and firm performance [17]), there is little direct empirical evidence of this relationship [7]. Our empirical results confirm that incremental and radical innovations have a significant positive impact on competitive advantage. Moreover, we find that radical innovation has a greater impact on a firm’s competitive advantage, supporting the idea that a firm’s possession of new and unique technological resources can help it gain a sustainable competitive advantage [94].

Second, this study reveals the mediating role of innovation speed in the relationship between incremental and radical innovation and competitive advantage; the findings contribute to the understanding of the importance of innovation speed in the innovation process of firms. On the one hand, the results suggest that innovation speed plays a partial mediating role between incremental innovation and competitive advantage. This supports the argument of Lin et al. [95] that accelerating incremental innovation can lead to a temporary competitive advantage for firms. On the other hand, the study found that innovation speed plays a fully mediating role between radical innovation and competitive advantage. This further confirms that speed-to-market radical innovations lead to a first-mover advantage and significant gains for firms [30]. As Cankurtaran et al. [33] argued, the timing of a new product’s entry into the market is critical, because missing a strategic window of opportunity can result in devastating opportunity costs [96].

Third, this study enriches the literature on organizational culture and innovation by uncovering the boundary conditions of a supportive culture. Our findings suggest that supportive culture positively moderates incremental and radical innovation and competitive advantage and that the moderating role is mediated by influencing the relationship between incremental and radical innovation and innovation speed. A supportive culture creates a trusting and safe organizational climate that helps foster teamwork and promotes knowledge-sharing and creativity [43]. Employees’ knowledge, experience, and skills can be more effectively transformed into resources for enterprise innovation. Therefore, the higher the degree of supportive culture in an enterprise, the more willing employees are to participate in innovation, which greatly improves the efficiency of incremental and radical innovation. The findings further support the view that organizational cultural context influences the relationship between innovation and competitive advantage [2,97].

5.2. Practical Implications

This study has several important practical implications. First, given the characteristics of low risk and fast returns for incremental innovation and high risk, as well as high benefits for radical innovation, firms should formulate incremental and radical innovation strategies flexibly to respond to changing market demands and competitive environments, to achieve a sustainable competitive advantage. Radical innovation can evolve into incremental innovation, while sustained incremental innovation can lead to radical innovation [19]. To better manage incremental and radical innovation, enterprises can set up communication platforms to acquire external knowledge, experience, and customer needs. At the same time, enterprises should increase investment in technological research and development, set up incentive mechanisms for innovation, attract and retain excellent talents, and improve innovation capability and innovation efficiency. Companies that fail to develop both radical and incremental innovation may be missing important opportunities for competitive success [98]. Second, to cope with the changing environment and limited resources, firms should adjust their resource allocation and strategies to increase innovation speed promptly. Managers must recognize the importance of speed-to-market in reducing costs and achieving a return on investment, whether the innovation is incremental or radical. Third, companies should focus on developing a strong internal culture, providing employees with an effective communication platform and skills training programs, encouraging employee learning and knowledge sharing and supporting employee innovative behaviors, to mobilize employee motivation and creativity, which is beneficial to improving the efficiency of incremental and radical innovation.

This study also provides some useful insights for policymakers. On the one hand, the government could provide financial support to encourage enterprises to provide relevant training courses and seminars on innovation capacity enhancement, to improve the innovation capacity and awareness of their employees, encourage enterprises to implement innovation-incentive mechanisms to support employee innovation, and actively and effectively achieve incremental innovation of enterprises to meet market demand. On the other hand, the government can promote cooperation among enterprises, universities, and scientific research institutions to facilitate the exchange of knowledge and technology, accelerate technological research and breakthroughs in key areas, and achieve radical innovations to create first-mover advantages.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Although this study makes several contributions to theory and practice, there are also several limitations. First, this study focuses on firms in China, which may limit the generalizability of the results to other regional or national contexts. It would be desirable and interesting to conduct similar studies elsewhere. Second, this study collected cross-sectional data using a questionnaire, which cannot explain the dynamic causal relationships, and future studies could use a longitudinal research design to explore the effects of incremental and radical innovation on competitive advantage at different stages of a firm’s life cycle. Moreover, when conducting questionnaires, there may be a social desirability bias, which is a limitation of self-reported data. Therefore, future studies may consider including both positive and negative statements in the questionnaire or a separate evaluation of independent variables and dependent variables to avoid such problems. Third, this study only considered the mediating effect of innovation speed; future studies could consider introducing other variables such as innovation quality and the interaction of innovation speed and quality [99]. In addition, some studies have shown that the results of incremental innovation have an impact on firms’ radical innovation performance [100]; future research could consider using radical innovation as a mediator to explore the impact of incremental innovation on firms’ competitive advantage. Fourth, this study only examined the moderating effect of supportive cultures; future research could explore additional contextual factors such as bureaucratic and innovative cultures [79]. Overall, future studies could consider introducing these variables to substantiate and extend our study.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version. H.X. performed conceptualization and project administration; X.C. performed methodology, writing—original draft, review, and editing; X.C. and H.Z. performed investigation and supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Social Science Foundation project (19BGL083).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Management, Zhejiang University of Technology (20240509).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to DeepL and Grammarly tools for providing high-quality translation polishing and grammar-checking services for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Gunday, G.; Ulusoy, G.; Kilic, K.; Alpkan, L. Effects of innovation types on firm performance. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2011, 133, 662–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbusch, N.; Brinckmann, J.; Bausch, A. Is innovation always beneficial? A meta-analysis of the relationship between innovation and performance in SMEs. J. Bus. Ventur. 2011, 26, 441–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lengnick-Hall, C.A. Innovation and Competitive Advantage: What We Know and What We Need to Learn. J. Manag. 1992, 18, 399–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Lai, S.B.; Wen, C.T. The Influence of Green Innovation Performance on Corporate Advantage in Taiwan. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 67, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerawardena, J.; Mavondo, F.T. Capabilities, innovation and competitive advantage. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2011, 40, 1220–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Peng, C.; Koo, B.; Zhang, G.; Yang, H. Obtaining sustainable competitive advantage through collaborative dual innovation: Empirical analysis based on mature enterprises in eastern China. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2021, 33, 685–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khatib, A.W.; Al-Ghanem, E.M. Radical innovation, incremental innovation, and competitive advantage, the moderating role of technological intensity: Evidence from the manufacturing sector in Jordan. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2022, 34, 344–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anning-Dorson, T. Innovation and competitive advantage creation: The role of organisational leadership in service firms from emerging markets. Int. Mark. Rev. 2018, 35, 580–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, G.M.; Styles, C.; Lages, L.F. Breakthrough innovation in international business: The impact of tech-innovation and market-innovation on performance. Int. Bus. Rev. 2017, 26, 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.; Lee, J.-H.; Garrett, T.C. Synergy effects of innovation on firm performance. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 99, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatignon, H.; Tushman, M.L.; Smith, W.; Anderson, P. A Structural Approach to Assessing Innovation: Construct Development of Innovation Locus, Type, and Characteristics. Manag. Sci. 2002, 48, 1103–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandy, R.K.; Tellis, G.J. The Incumbent’s Curse? Incumbency, Size, and Radical Product Innovation. J. Mark. 2000, 64, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tushman, M.L.; Anderson, P. Technological Discontinuities and Organizational Environments. Adm. Sci. Q. 1986, 31, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewar, R.D.; Dutton, J.E. The Adoption of Radical and Incremental Innovations: An Empirical Analysis. Manag. Sci. 1986, 32, 1422–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouncken, R.B.; Fredrich, V.; Ritala, P.; Kraus, S. Coopetition in New Product Development Alliances: Advantages and Tensions for Incremental and Radical Innovation. Br. J. Manag. 2018, 29, 391–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccia, M. Sources of technological innovation: Radical and incremental innovation problem-driven to support competitive advantage of firms. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2017, 29, 1048–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freixanet, J.; Rialp, J. Disentangling the relationship between internationalization, incremental and radical innovation, and firm performance. Glob. Strategy J. 2022, 12, 57–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennerts, S.; Schulze, A.; Tomczak, T. The asymmetric effects of exploitation and exploration on radical and incremental innovation performance: An uneven affair. Eur. Manag. J. 2020, 38, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souto, J.E. Business model innovation and business concept innovation as the context of incremental innovation and radical innovation. Tour. Manag. 2015, 51, 142–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banbury, C.M.; Mitchell, W. The effect of introducing important incremental innovations on market share and business survival. Strateg. Manag. J. 1995, 16, 161–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaskaran, S. Incremental Innovation and Business Performance: Small and Medium-Size Food Enterprises in a Concentrated Industry Environment. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2006, 44, 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadarajan, R. Fortune at the bottom of the innovation pyramid: The strategic logic of incremental innovations. Bus. Horiz. 2009, 52, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leifer, R.; O’Connor, G.C.; Rice, M. Implementing radical innovation in mature firms: The role of hubs. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2001, 15, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.Z.; Li, C.B. How knowledge affects radical innovation: Knowledge base, market knowledge acquisition, and internal knowledge sharing. Strateg. Manag. J. 2012, 33, 1090–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, D.A.; Verganti, R. Incremental and Radical Innovation: Design Research vs. Technology and Meaning Change. Des. Issues 2014, 30, 78–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiberius, V.; Schwarzer, H.; Roig-Dobón, S. Radical innovations: Between established knowledge and future research opportunities. J. Innov. Knowl. 2021, 6, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzoglou, P.; Chatzoudes, D. The role of innovation in building competitive advantages: An empirical investigation. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2018, 21, 44–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baierle, I.C.; Benitez, G.B.; Nara, E.O.B.; Schaefer, J.L.; Sellitto, M.A. Influence of Open Innovation Variables on the Competitive Edge of Small and Medium Enterprises. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Fang, C.-C. The influence of corporate networks on competitive advantage: The mediating effect of ambidextrous innovation. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2022, 34, 946–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allocca, M.A.; Kessler, E.H. Innovation Speed in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2006, 15, 279–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrens, J.; Patzelt, H. Incentives, Resources and Combinations of Innovation Radicalness and Innovation Speed. Br. J. Manag. 2018, 29, 691–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briest, G.; Lukas, E.; Mölls, S.H.; Willershausen, T. Innovation speed under uncertainty and competition. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2020, 41, 1517–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cankurtaran, P.; Langerak, F.; Griffin, A. Consequences of New Product Development Speed: A Meta-Analysis. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2013, 30, 465–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, A.; Chowdhury, J.; Lukas, B.A. Antecedents and outcomes of new product development speed An interdisciplinary conceptual framework. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2002, 31, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Reilly, R.R.; Lynn, G.S. New Product Development Speed: Too Much of a Good Thing?: New Product Development Speed. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2012, 29, 288–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, E.H.; Bierly, P.E. Is faster really better? An empirical test of the implications of innovation speed. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2002, 49, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Xiao, Z.; Dong, M.C.; Gu, J. The fit between firms’ open innovation and business model for new product development speed: A contingent perspective. Technovation 2019, 86–87, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Dong, J.; Mei, L.; Shen, R. Digital innovation and performance of manufacturing firms: An affordance perspective. Technovation 2023, 119, 102458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turró, A.; Urbano, D.; Peris-Ortiz, M. Culture and innovation: The moderating effect of cultural values on corporate entrepreneurship. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2014, 88, 360–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeem, M.; Ahmed, M.; Haider, S.; Sajjad, M. Expanding competitive advantage through organizational culture, knowledge sharing and organizational innovation. Technol. Soc. 2021, 66, 101635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaliza, J.A.A.; Jugend, D.; Chiappetta Jabbour, C.J.; Latan, H.; Armellini, F.; Twigg, D.; Andrade, D.F. Relationships among organizational culture, open innovation, innovative ecosystems, and performance of firms: Evidence from an emerging economy context. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 140, 264–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyar, M.N.; Rafi, N. ‘Organizational learning culture’: An ingenious device for promoting firm’s innovativeness. Serv. Ind. J. 2013, 33, 1135–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.-H.; Chang, W.-J.; Hu, D.-C.; Yueh, Y.-L. Relationships among organizational culture, knowledge acquisition, organizational learning, and organizational innovation in Taiwan’s banking and insurance industries. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 23, 52–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.-H.; Hu, D.-C.; Chen, C.-C.; Lin, Y.-L. Comparison of competing models and multi-group analysis of organizational culture, knowledge transfer, and innovation capability: An empirical study of the Taiwan semiconductor industry. Knowl. Man. Res. Pract. 2013, 13, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Men, L.R.; Yue, C.A. Creating a positive emotional culture: Effect of internal communication and impact on employee supportive behaviors. Public Relat. Rev. 2019, 45, 101764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, A.; Kalia, P. Examining the effects of supportive work environment and organisational learning culture on organisational performance in information technology companies: The mediating role of learning agility and organisational innovation. Innov. Manag. 2022, 26, 257–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volery, T.; Tarabashkina, L. The impact of organisational support, employee creativity and work centrality on innovative work behaviour. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 129, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, W.; Cluley, R. The field of radical innovation: Making sense of organizational cultures and radical innovation. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2014, 43, 1343–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, P.B.; Lei, H.; Le, T.T.; Gong, J.; Ha, A.T. Developing a collaborative culture for radical and incremental innovation: The mediating roles of tacit and explicit knowledge sharing. Chin. Manag. Stud. 2020, 14, 957–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benner, M.J.; Tushman, M. Process Management and Technological Innovation: A Longitudinal Study of the Photography and Paint Industries. Adm. Sci. Q. 2002, 47, 676–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbig, P.; Golden, J.E.; Dunphy, S. The Relationship of Structure to Entrepreneurial and Innovative Success. Mark. Intell. Plan. 1994, 12, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.; Selen, W. The incremental and cumulative effects of dynamic capability building on service innovation in collaborative service organizations. J. Manag. Organ. 2013, 19, 521–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berggren, C. The cumulative power of incremental innovation and the role of project sequence management. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2019, 37, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos-Brouwers, H.E.J. Corporate sustainability and innovation in SMEs: Evidence of themes and activities in practice. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2010, 19, 417–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Wu, J.; Gu, J.; Raza-Ullah, T. How inter-firm cooperation and conflicts in industrial clusters influence new product development performance? The role of firm innovation capability. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2023, 111, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusof, N.A.; Kamal, E.M.; Lou, E.C.W.; Kamaruddeen, A.M. Effects of innovation capability on radical and incremental innovations and business performance relationships. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. 2023, 67, 101726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Li, H.; Xu, J.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.Z.; Wu, Y. The effect of internal quality integration on financial performance: The mediating role of product innovation. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2023, 34, 1235–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huvaj, M.N.; Johnson, W.C. Organizational complexity and innovation portfolio decisions: Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 98, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevil, A.; Cruz, A.; Reyes, T.; Vassolo, R. When Being Large Is Not an Advantage: How Innovation Impacts the Sustainability of Firm Performance in Natural Resource Industries. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koberg, C.S.; Detienne, D.R.; Heppard, K.A. An empirical test of environmental, organizational, and process factors affecting incremental and radical innovation. J. High Technol. Manag. Res. 2003, 14, 21–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlin, K.B.; Behrens, D.M. When is an invention really radical?Defining and measuring technological radicalness. Res. Policy 2005, 34, 717–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, S.K.; Oh, J.-M.; Xia, H. Incremental vs. Breakthrough Innovation: The Role of Technology Spillovers. Manag. Sci. 2021, 67, 1779–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhou, K.Z. External learning, market dynamics, and radical innovation: Evidence from China’s high-tech firms. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1226–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, M.L.; Chien, I. Rethinking organizational learning orientation on radical and incremental innovation in high-tech firms. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2302–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giachetti, C.; Li Pira, S. Catching up with the market leader: Does it pay to rapidly imitate its innovations? Res. Policy. 2022, 51, 104505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Hughes, M. Radical innovation in family firms: A systematic analysis and research agenda. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2020, 26, 1199–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, S.F.; Mohr, J.J.; Sengupta, S. Radical Product Innovation Capability: Literature Review, Synthesis, and Illustrative Research Propositions. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2014, 31, 552–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.W.L.; Rothaermel, F.T. The Performance of Incumbent Firms in the Face of Radical Technological Innovation. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2003, 28, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gao, J.; Wei, Z. The double-edged sword of servitization in radical product innovation: The role of latent needs identification. Technovation 2022, 118, 102284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, E.H.; Chakrabarti, A.K. Speeding Up the Pace of New Product Development. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 1999, 16, 231–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanko, M.A.; Molina-Castillo, F.J.; Munuera-Aleman, J.L. Speed to Market for Innovative Products: Blessing or Curse? J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2012, 29, 751–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, P.; Song, M.; Ju, X. Entrepreneurial orientation and performance: Is innovation speed a missing link? J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 683–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, M.; Youndt, M.A. The Influence of Intellectual Capital on the Types of Innovative Capabilities. Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 48, 450–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H. The Effect of New Product Radicality and Scope on the Extent and Speed of Innovation Diffusion. J. Manag. 2003, 29, 753–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schein, E.H. Coming to a New Awareness of Organizational Culture. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 1984, 25, 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, J.B. Firm Resource and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallach, E.J. Individuals and organizations: The cultural match. Train. Dev. J. 1983, 37, 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, R.; Li, Y.; Huang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, R.; Dunlop, E. Psychological capital and breakthrough innovation: The role of tacit knowledge sharing and task interdependence. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1097936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huey Yiing, L.; Zaman Bin Ahmad, K. The moderating effects of organizational culture on the relationships between leadership behaviour and organizational commitment and between organizational commitment and job satisfaction and performance. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2009, 30, 53–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berson, Y.; Oreg, S.; Dvir, T. CEO values, organizational culture and firm outcomes. J. Organ. Behav. 2008, 29, 615–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail Ababaneh, R. The role of organizational culture on practising quality improvement in Jordanian public hospitals. Leadersh. Health Serv. 2010, 23, 244–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Un, C.A. An empirical multi-level analysis for achieving balance between incremental and radical innovations. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. 2010, 27, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, M.; Moen, O.; Brett, P.O. The organizational climate for psychological safety: Associations with SMEs’ innovation capabilities and innovation performance. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. 2020, 55, 101554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonell, P.; Rodríguez-Escudero, A.I. Relationships among team’s organizational context, innovation speed, and technological uncertainty: An empirical analysis. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. 2009, 26, 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, B.; Bhattacharyya, S.S.; Krishnamoorthy, B. Exploring the black box of competitive advantage—An integrated bibliometric and chronological literature review approach. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 139, 964–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonell, P.; Rodríguez-Escudero, A.I.; Pujari, D. Customer Involvement in New Service Development: An Examination of Antecedents and Outcomes. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2009, 26, 536–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; p. 692. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.t.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalal, D.K.; Zickar, M.J. Some Common Myths About Centering Predictor Variables in Moderated Multiple Regression and Polynomial Regression. Organ. Res. Methods 2012, 15, 339–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. An Index and Test of Linear Moderated Mediation. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2015, 50, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, K.-F.; Dyerson, R.; Wu, L.-Y.; Harindranath, G. From Temporary Competitive Advantage to Sustainable Competitive Advantage: From Temporary to Sustainable Competitive Advantage. Br. J. Manag. 2015, 26, 617–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.-J.J.; Huang, C.-H.; Chiang, I.-C. Explaining trade-offs in new product development speed, cost, and quality: The case of high-tech industry in Taiwan. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2012, 23, 1107–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaner, M.B.; Fenik, A.P.; Noble, C.H.; Lee, K.B. Exploring the need for (extreme) speed: Motivations for and outcomes of discontinuous NPD acceleration. J. Mark. Manag. 2020, 36, 727–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, S.J.; Coote, L.V. Organizational culture, innovation, and performance: A test of Schein's model. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1609–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.; Franke, G.R.; Butler, T.D.; Musgrove, C.F.; Ellinger, A.E. Differential Mediating Effects of Radical and Incremental Innovation on Market Orientation-Performance Relationship: A Meta-Analysis. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2014, 22, 235–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Bo, Q.; Tong, X.; Zhang, X. A paradoxical view of speed and quality on operational outcome: An empirical investigation of innovation in high-tech small and medium-sized enterprises. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 229, 107780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albors-Garrigos, J.; Igartua, J.I.; Peiro, A. Innovation management techniques and tools: Its impact on firm innovation performance. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2018, 22, 1850051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).