Facilitating the Smooth Migration of Inhabitants of Atoll Countries to Artificial Islands: Case of the Maldives

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Research Area

2.2. Design of the Questionnaire Survey

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney Test

3.2. Permutation Feature Importance

- x11—Clean new home

- x23—Resilience to natural disasters

- x9—Sports facilities and parks

- x20—No air and water pollution

- x25—Territorial integrity

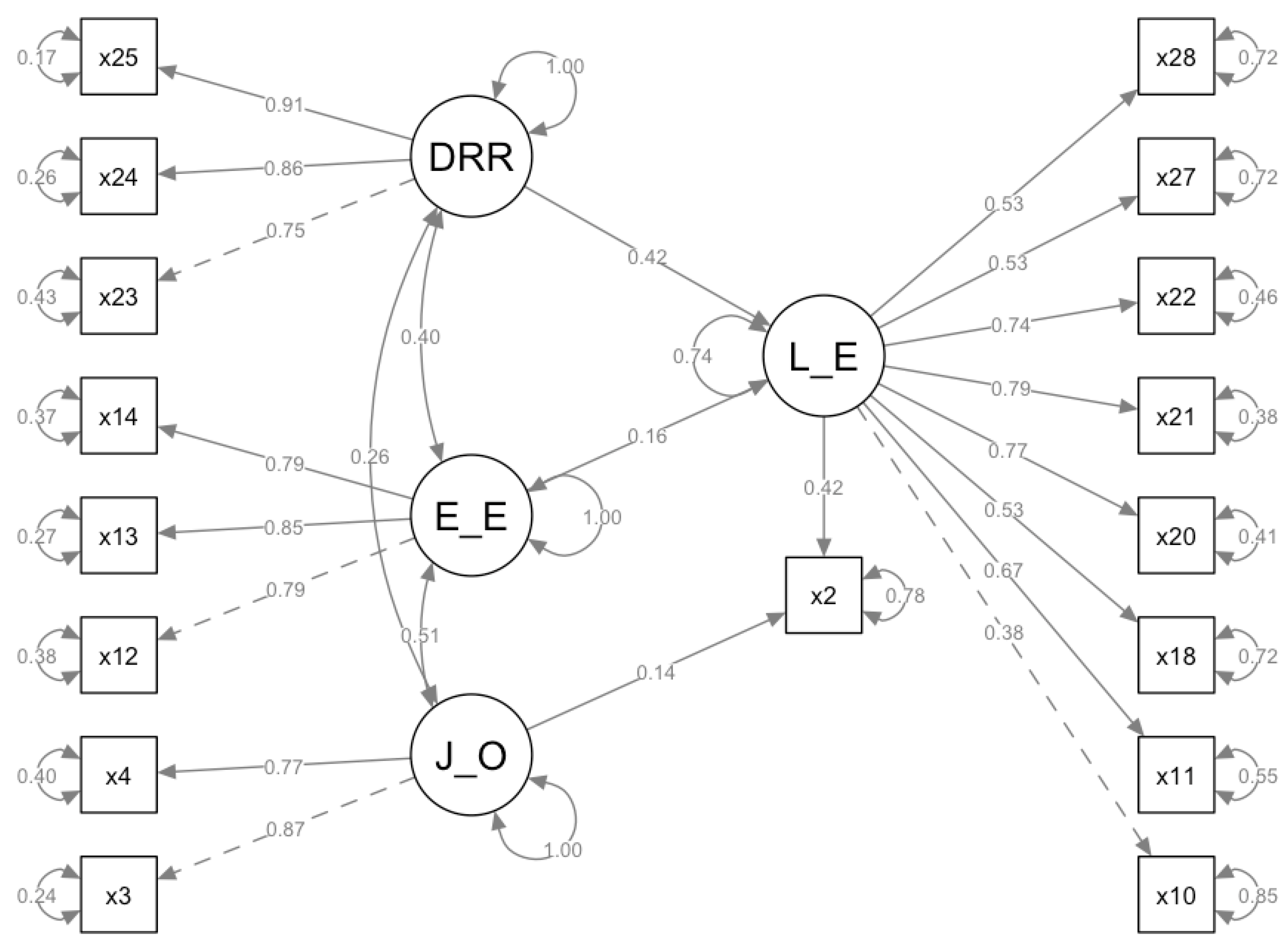

3.3. Structural Equation Modeling

3.4. Overall Implications

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Masson-Delmotte, V.; Zhai, P.; Pirani, A.; Connors, S.L.; Péan, C.; Berger, S.; Caud, N.; Chen, Y.; Goldfarb, L.; Gomis, M.I. (Eds.) IPCC, Summary for policymakers. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Environment and Energy (MEE). Second National Communication of Maldives to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change; Ministry of Environment and Energy, Republic of Maldives: Malé, Maldives, 2016; Available online: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/SNC%20PDFResubmission.pdf (accessed on 24 July 2023).

- Sasaki, D. Analysis of the attitude within Asia-Pacific countries towards disaster risk reduction: Text mining of the official statements of 2018 Asian ministerial conference on disaster risk reduction. J. Disaster Res. 2019, 14, 1024–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharon, O. To be or not to be: State extinction through climate change. SSRN J. 2021, 51, 1041–1083. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/48647569 (accessed on 24 July 2023).

- Nakayama, M.; Fujikura, R.; Okuda, R.; Fujii, M.; Takashima, R.; Murakawa, T.; Sakai, E.; Iwama, H. Alternatives for the Marshall Islands to cope with the anticipated sea level rise by climate change. J. Disaster Res. 2022, 17, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt di Friedberg, M.S.; Malatesta, S.; dell’Agnese, E. Hazard, resilience and development: The case of two Maldivian islands. BSGI 2020, 11, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, K.N. Trade and Civilisation in the Indian Ocean: An Economic History from the Rise of Islam to 1750; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Duvat, V.K.E.; Magnan, A.K. Rapid human-driven undermining of atoll island capacity to adjust to ocean climate-related pressures. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 15129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luetz, J. Climate Change and Migration in the Maldives: Some Lessons for Policy Makers. In Climate Change Adaptation in Pacific Countries: Fostering Resilience and Improving the Quality of Life; Filho, W.L., Nalau, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 35–69. [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto, A.; Nishiya, K.; Guo, X.; Sugimoto, A.; Nagasaki, W.; Doi, K. Mitigating impacts of climate change induced sea level rise by infrastructure development: Case of the Maldives. J. Disaster Res. 2022, 17, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gussmann, G.; Hinkel, J. A framework for assessing the potential effectiveness of adaptation policies: Coastal risks and sea-level rise in the Maldives. Environ. Sci. Policy 2021, 115, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.; Wadey, M.P.; Nicholls, R.J.; Shareef, A.; Khaleel, Z.; Hinkel, J.; Lincke, D.; McCabe, M.V. Land raising as a solution to sea-level rise: An analysis of coastal flooding on an artificial island in the Maldives. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2020, 13, e12567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohit, M.A.; Azim, M. Assessment of residential satisfaction with public housing in Hulhumale’, Maldives. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 50, 756–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, D.; Jibiki, Y.; Ohkura, T. Tourists’ behavior for volcanic disaster risk reduction: A case study of Mount Aso in Japan. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 78, 103142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altmann, A.; Toloşi, L.; Sander, O.; Lengauer, T. Permutation importance: A corrected feature importance measure. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 1340–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pesarin, F.; Salmaso, L. Permutation Tests for Complex Data: Theory, Applications, and Software; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tarka, P. An overview of structural equation modeling: Its beginnings, historical development, usefulness, and controversies in the social sciences. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 313–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasaki, D.; Moriyama, K.; Ono, Y. Main features of the existing literature concerning disaster statistics. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 43, 101382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, D.; Moriyama, K.; Ono, Y. Hidden common factors in disaster loss statistics: A case study analyzing the data of Nepal. J. Disaster Res. 2018, 13, 1032–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, D.; Taafaki, I.; Uakeia, T.; Seru, J.; McKay, Y.; Lajar, H. Influence of religion, culture and education on perception of climate change and its implications: Applying structural equation modeling (SEM). J. Disaster Res. 2019, 14, 1303–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabchuk, T.; Katsaiti, M.; Johnson, K.A. Life satisfaction and desire to emigrate: What does the cross-national analysis show? Int. Migr. 2022, 61, 349–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Question No. | Question |

|---|---|

| c1 | Age |

| c2 | Sex |

| c3 | Education level |

| c4 | Year of migration to Hulhumalé |

| c5 | Pre-migration settlement |

| c6 | Occupation before migration |

| c7 | Occupation after migration |

| c8 | Annual personal income before migration |

| c9 | Annual personal income after migration |

| c10 | Reason for moving to Hulhumalé |

| c11 | Interest in returning to the place where you lived before moving to Hulhumalé |

| Question No. | Question |

|---|---|

| x1 | You were satisfied with your life before you moved to Hulhumalé. |

| x2 | You are satisfied with your life at the moment. |

| x3 | There are many opportunities for high-paying jobs. |

| x4 | There are many opportunities for non-physical work. |

| x5 | The cost of living is low. |

| x6 | A wide range of dining, shopping, hotels, and entertainment options are available. |

| x7 | Many hospitals make it easy for people to access medical care. |

| x8 | A high level of medical care is available (e.g., for serious illnesses such as cancer). |

| x9 | Many sports facilities and parks provide environments for people to maintain their health through exercise. |

| x10 | Rent or house acquisition cost is low. |

| x11 | There are many opportunities to live in a clean new home. |

| x12 | The quality of primary education is good. |

| x13 | The quality of higher education is good. |

| x14 | Tutoring and learning opportunities are widely available. |

| x15 | Links are maintained between people from pre-migration settlements. |

| x16 | There are many opportunities to gain new friends and partners. |

| x17 | Many local community activities are available. |

| x18 | There are good neighborly relations. |

| x19 | Great efforts have been made to preserve the local and traditional culture in various parts of the Maldives. |

| x20 | The living environment is healthy without air and water pollution. |

| x21 | The living environment is kept clean, with proper waste collection and cleaning of public areas. |

| x22 | There are beautiful and rich natural surroundings. |

| x23 | Hulhumalé is resilient to natural disasters, such as cyclones, storm surges, flooding, and water shortages. |

| x24 | Hulhumalé is safe against sea level rise due to climate change. |

| x25 | Hulhumalé ensures the territorial integrity of the Maldives in the event of a rise in sea level. |

| x26 | Lives are safeguarded by the police. |

| x27 | The public manners of the people are good. |

| x28 | Infrastructure such as electricity, gas, water, sewage, and telecommunications are in place. |

| x29 | Transport infrastructure, including public transport, is well developed. |

| x30 | Transport links are well-developed throughout the Maldives. |

| x31 | Transport links to international airports (abroad) are well developed. |

| x32 | There are good quality administrative services. |

| Mean | Median | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| x1 | Satisfaction before migration | 3 | 3 |

| x2 | Satisfaction after migration | 3.7 | 4 |

| Rank | Mean | Median | Rank | Mean | Median | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x28 | Utility infrastructure | 1 | 3.7 | 4 | x10 | Rent or house acquisition cost | 30 | 1.7 | 1 |

| x22 | Beautiful and rich natural surroundings | 2 | 3.5 | 4 | x5 | Cost of living | 29 | 1.8 | 1 |

| x9 | Sports facilities and parks | 3 | 3.4 | 4 | x26 | Safeguarded by the police | 28 | 2.2 | 2 |

| x29 | Transportation in the island | 3 | 3.4 | 3 | x19 | Preserve local and traditional culture | 26 | 2.3 | 2 |

| x31 | Transport links (abroad) | 3 | 3.4 | 4 | x27 | Public manners | 26 | 2.3 | 2 |

| x20 | No air and water pollution | 6 | 3.3 | 4 | x3 | High-paying jobs | 25 | 2.4 | 2 |

| Attribute | Category 1 | Category 2 | Number of Samples of Category 1 | Number of Samples of Category 2 | Total Number of Samples | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c1 | Age | 20–29 years old | More than 50 years old | 69 | 20 | 89 |

| c2 | Sex | Male | Female | 114 | 138 | 252 |

| c3 | Education level | O’Level | First Degree & Higher | 35 | 137 | 172 |

| c5 | Pre-migration settlement | Malé | Other cities | 193 | 59 | 252 |

| c8 | Annual personal income before migration | Less than Rf. 29,999 | More than Rf. 210,000 | 141 | 31 | 172 |

| c9 | Annual personal income after migration | Less than Rf. 29,999 | More than Rf. 210,000 | 111 | 49 | 160 |

| c11 | Interest in returning to the place where you lived before moving to Hulhumalé | Yes or undecided | No | 75 | 177 | 252 |

| Question | Attribute | Category 1 | Category 2 | p Value | p Value < | |||

| Mean | Median | Mean | Median | |||||

| x1 | Satisfaction before migration | c5 | 2.85 | 3 | 3.46 | 4 | 0.00079 | 0.01 |

| c11 | 3.35 | 3 | 2.84 | 3 | 0.00184 | 0.01 | ||

| x2 | Satisfaction after migration | c5 | 3.76 | 4 | 3.31 | 4 | 0.04854 | 0.05 |

| c11 | 3.17 | 3 | 3.85 | 4 | 0.00011 | 0.01 | ||

| x3 | High-paying job | c1 | 2.64 | 3 | 1.95 | 2 | 0.02402 | 0.05 |

| c2 | 2.65 | 3 | 2.2 | 2 | 0.00563 | 0.01 | ||

| c5 | 2.21 | 2 | 3.05 | 3 | 0.00004 | 0.01 | ||

| c11 | 2.76 | 3 | 2.25 | 2 | 0.00856 | 0.01 | ||

| x4 | Non-physical work | c1 | 2.9 | 3 | 1.95 | 2 | 0.00029 | 0.01 |

| c2 | 2.82 | 3 | 2.43 | 2 | 0.00678 | 0.01 | ||

| c5 | 2.45 | 2 | 3.1 | 3 | 0.00017 | 0.01 | ||

| x5 | Cost of living | c5 | 1.96 | 2 | 1.44 | 1 | 0.00007 | 0.01 |

| x6 | Wide choice of entertainment | c5 | 2.64 | 3 | 3.24 | 3 | 0.00206 | 0.01 |

| x8 | High level of medical care | c1 | 2.9 | 3 | 1.9 | 2 | 0.00213 | 0.01 |

| c11 | 2.24 | 2 | 2.66 | 3 | 0.03602 | 0.05 | ||

| x9 | Sports facilities and parks | c9 | 3.24 | 4 | 3.69 | 4 | 0.04348 | 0.05 |

| c11 | 2.99 | 3 | 3.59 | 4 | 0.00069 | 0.01 | ||

| x10 | Rent or house acquisition cost | c5 | 1.74 | 1 | 1.37 | 1 | 0.00358 | 0.01 |

| x11 | Clean new home | c5 | 3.21 | 3 | 2.75 | 3 | 0.01222 | 0.05 |

| c11 | 2.68 | 3 | 3.28 | 3 | 0.00061 | 0.01 | ||

| x12 | Quality of primary education | c1 | 3.46 | 4 | 2.8 | 3 | 0.0127 | 0.05 |

| c5 | 3.06 | 3 | 3.44 | 4 | 0.0106 | 0.05 | ||

| x13 | Quality of higher education | c3 | 3.29 | 3 | 2.47 | 3 | 0.00056 | 0.01 |

| c5 | 2.41 | 2 | 3.24 | 3 | 0.00001 | 0.01 | ||

| x14 | Tutoring and learning opportunities | c1 | 3.22 | 3 | 2.45 | 3 | 0.00324 | 0.01 |

| c5 | 2.66 | 3 | 3.25 | 3 | 0.00025 | 0.01 | ||

| x15 | Links of people before migration | c1 | 3.38 | 3 | 2.75 | 3 | 0.01945 | 0.05 |

| x19 | Preservation of local and traditional culture | c2 | 2.46 | 3 | 2.21 | 2 | 0.03411 | 0.05 |

| x20 | No air and water pollution | c11 | 2.96 | 3 | 3.46 | 4 | 0.00424 | 0.01 |

| c5 | 3.41 | 4 | 2.98 | 3 | 0.02173 | 0.05 | ||

| c9 | 3.08 | 3 | 3.49 | 4 | 0.03607 | 0.05 | ||

| x22 | Beautiful and rich natural surroundings | c2 | 3.4 | 3 | 3.66 | 4 | 0.02445 | 0.05 |

| c11 | 3.21 | 3 | 3.68 | 4 | 0.00149 | 0.01 | ||

| x23 | Resilience to natural disasters | c1 | 3.22 | 3 | 2.7 | 3 | 0.04616 | 0.05 |

| x25 | Territorial integrity | c2 | 3 | 3 | 2.71 | 3 | 0.03705 | 0.05 |

| x27 | Public manners | c3 | 2.71 | 3 | 2.26 | 2 | 0.0436 | 0.05 |

| x28 | Utility infrastructure | c8 | 3.56 | 4 | 3.94 | 4 | 0.02219 | 0.05 |

| c9 | 3.5 | 4 | 3.96 | 4 | 0.00476 | 0.01 | ||

| x29 | Transportation in the island | c1 | 3.65 | 4 | 2.95 | 3 | 0.01893 | 0.05 |

| x32 | Administrative services | c1 | 2.75 | 3 | 2.15 | 2 | 0.02823 | 0.05 |

| c11 | 2.24 | 2 | 2.65 | 3 | 0.00651 | 0.01 | ||

| Question | Attribute | Category 1 | Category 2 | p Value | p Value < | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Median | Mean | Median | |||||

| x3 | High-paying jobs | c1 | 2.64 | 3 | 1.95 | 2 | 0.02402 | 0.05 |

| x4 | Non-physical work | 2.9 | 3 | 1.95 | 2 | 0.00029 | 0.01 | |

| x8 | High level of medical care | 2.9 | 3 | 1.9 | 2 | 0.00213 | 0.01 | |

| x12 | Quality of primary education | 3.46 | 4 | 2.8 | 3 | 0.0127 | 0.05 | |

| x14 | Tutoring and learning opportunities | 3.22 | 3 | 2.45 | 3 | 0.00324 | 0.01 | |

| x15 | Links of people before migration | 3.38 | 3 | 2.75 | 3 | 0.01945 | 0.05 | |

| x23 | Resilience to natural disasters | 3.22 | 3 | 2.7 | 3 | 0.04616 | 0.05 | |

| x29 | Transportation in the island | 3.65 | 4 | 2.95 | 3 | 0.01893 | 0.05 | |

| x32 | Administrative services | 2.75 | 3 | 2.15 | 2 | 0.02823 | 0.05 | |

| x3 | High-paying jobs | c2 | 2.65 | 3 | 2.2 | 2 | 0.00563 | 0.01 |

| x4 | Non-physical work | 2.82 | 3 | 2.43 | 2 | 0.00678 | 0.01 | |

| x19 | Preservation of local and traditional culture | 2.46 | 3 | 2.21 | 2 | 0.03411 | 0.05 | |

| x22 | Beautiful and rich natural surroundings | 3.4 | 3 | 3.66 | 4 | 0.02445 | 0.05 | |

| x25 | Territorial integrity | 3 | 3 | 2.71 | 3 | 0.03705 | 0.05 | |

| x13 | Quality of higher education | c3 | 3.29 | 3 | 2.47 | 3 | 0.00056 | 0.01 |

| x27 | Public manners | 2.71 | 3 | 2.26 | 2 | 0.0436 | 0.05 | |

| x1 | Satisfaction before migration | c5 | 2.85 | 3 | 3.46 | 4 | 0.00079 | 0.01 |

| x2 | Satisfaction after migration | 3.76 | 4 | 3.31 | 4 | 0.04854 | 0.05 | |

| x3 | High-paying jobs | 2.21 | 2 | 3.05 | 3 | 0.00004 | 0.01 | |

| x4 | Non-physical work | 2.45 | 2 | 3.1 | 3 | 0.00017 | 0.01 | |

| x5 | Cost of living | 1.96 | 2 | 1.44 | 1 | 0.00007 | 0.01 | |

| x6 | Wide choice of entertainment | 2.64 | 3 | 3.24 | 3 | 0.00206 | 0.01 | |

| x10 | Rent or house acquisition cost | 1.74 | 1 | 1.37 | 1 | 0.00358 | 0.01 | |

| x11 | Clean new home | 3.21 | 3 | 2.75 | 3 | 0.01222 | 0.05 | |

| x12 | Quality of primary education | 3.06 | 3 | 3.44 | 4 | 0.0106 | 0.05 | |

| x13 | Quality of higher education | 2.41 | 2 | 3.24 | 3 | 0.00001 | 0.01 | |

| x14 | Tutoring and learning opportunities | 2.66 | 3 | 3.25 | 3 | 0.00025 | 0.01 | |

| x20 | No air and water pollution | 3.41 | 4 | 2.98 | 3 | 0.02173 | 0.05 | |

| x28 | Utility infrastructure | c8 | 3.56 | 4 | 3.94 | 4 | 0.02219 | 0.05 |

| x9 | Sports facilities and parks | c9 | 3.24 | 4 | 3.69 | 4 | 0.04348 | 0.05 |

| x20 | No air and water pollution | 3.08 | 3 | 3.49 | 4 | 0.03607 | 0.05 | |

| x28 | Utility infrastructure | 3.5 | 4 | 3.96 | 4 | 0.00476 | 0.01 | |

| x1 | Satisfaction before migration | c11 | 3.35 | 3 | 2.84 | 3 | 0.00184 | 0.01 |

| x2 | Satisfaction after migration | 3.17 | 3 | 3.85 | 4 | 0.00011 | 0.01 | |

| x3 | High-paying jobs | 2.76 | 3 | 2.25 | 2 | 0.00856 | 0.01 | |

| x8 | High level of medical care | 2.24 | 2 | 2.66 | 3 | 0.03602 | 0.05 | |

| x9 | Sports facilities and parks | 2.99 | 3 | 3.59 | 4 | 0.00069 | 0.01 | |

| x11 | Clean new home | 2.68 | 3 | 3.28 | 3 | 0.00061 | 0.01 | |

| x20 | No air and water pollution | 2.96 | 3 | 3.46 | 4 | 0.00424 | 0.01 | |

| x22 | Beautiful and rich natural surroundings | 3.21 | 3 | 3.68 | 4 | 0.00149 | 0.01 | |

| x32 | Administrative services | 2.24 | 2 | 2.65 | 3 | 0.00651 | 0.01 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sasaki, D.; Sakamoto, A.; Laila, A.; Aslam, A.; Feng, S.; Kaku, T.; Sasaki, T.; Shinomura, N.; Nakayama, M. Facilitating the Smooth Migration of Inhabitants of Atoll Countries to Artificial Islands: Case of the Maldives. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4582. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16114582

Sasaki D, Sakamoto A, Laila A, Aslam A, Feng S, Kaku T, Sasaki T, Shinomura N, Nakayama M. Facilitating the Smooth Migration of Inhabitants of Atoll Countries to Artificial Islands: Case of the Maldives. Sustainability. 2024; 16(11):4582. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16114582

Chicago/Turabian StyleSasaki, Daisuke, Akiko Sakamoto, Aishath Laila, Ahmed Aslam, Shuxian Feng, Takuto Kaku, Takumi Sasaki, Natsuya Shinomura, and Mikiyasu Nakayama. 2024. "Facilitating the Smooth Migration of Inhabitants of Atoll Countries to Artificial Islands: Case of the Maldives" Sustainability 16, no. 11: 4582. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16114582

APA StyleSasaki, D., Sakamoto, A., Laila, A., Aslam, A., Feng, S., Kaku, T., Sasaki, T., Shinomura, N., & Nakayama, M. (2024). Facilitating the Smooth Migration of Inhabitants of Atoll Countries to Artificial Islands: Case of the Maldives. Sustainability, 16(11), 4582. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16114582