Abstract

Entrepreneurship research has developed in the last twenty years and now the focus is on Strategic Entrepreneurship (SE). SE can provide the sustainable growth of an organisation and increase its competitiveness globally. Despite these advantages, developing countries cannot reap the benefits of SE due to various barriers. Therefore, this study aims to identify and model the barriers of SE to the development of organisational management. Initially, the barriers of SE are identified through a literature review and further validated with a domain expert. The causal relationship among the barriers is modelled using the decision-making trial and evaluation laboratory (DEMATEL) method. The result suggests that low awareness of SE, risk aversion, and low financial support are the major barriers in the development of SE that need to be mitigated. Further, this analysis also categorises these barriers into a cause-and-effect group. Six barriers belong to the cause group and the remaining four are part of the effect group. Knowledge of the barriers is helpful for policymakers to design development strategies and helps business development managers in the successive planning of the organisation. The understanding of the interrelationship among the barriers will help the organisation to remove these barriers in an optimal manner. The findings of the study will be helpful for top management and strategic planners to advance design thinking and strategic planning. The contribution of this research lies in the identification of barriers to SE and their causal relationships, which have been scarcely examined in the existing literature.

1. Introduction

In the last few years, economies have been transforming from an industrial to a knowledge-based economy. Entrepreneurship development has become a major part of these knowledge economies because it has the power to drive the world economy in general and developing countries in particular. Therefore, the research in the area of SE development emerges as a significant research area [1]. Both entrepreneurship and strategic management are required for the growth and wealth generation of an organisation [2]. Suriyankietkaew et al. [3], through a bibliometric review, illustrated how strategic management can be used to achieve all three dimensions of sustainability. Entrepreneurship has, as its primary objectives, the expansion of an enterprise and the generation of wealth [4,5]. This is true for all economic types, whether developed or developing [6]. Strategic management contributes considerably to the comprehension of the disparities in wealth development between economies [7]. The relationship between growth and wealth creation is based on the fact that growth enables enterprises to generate money through economies of scale and market dominance. With these results, businesses can generate new resources and acquire a competitive advantage. In the same manner, increased money enables businesses to develop new resources that encourage growth.

SE has garnered increasing scholarly interest in recent years due to its practical importance, and study on the notion of SE has increased greatly since its origin, resulting in a vast research and literature domain [8]. Many researchers emphasise the identification of the growth prospects in SE [9,10]. SE is receiving attention because it supports firms to innovate in terms of employees’ abilities and skill development and creating innovative ventures [11]. SE integrates entrepreneurship and strategic management, highlighting the significance of culture, leadership, resources, and innovation in creating sustainable value [1].

Recently, most firms have engaged in entrepreneurial activities and innovations that create value for society [12,13]. SE tends to integrate opportunity-seeking as well as advantage-seeking behaviours. This implies that SE entails efforts designed to capitalise on the available advantages within the organisation; in addition, it also creates new prospects that will sustain an organisation’s potential to generate value over time. SE can add value to firms by producing more precisely and efficiently, resulting in responsive and adaptable goods and services, thereby making them more sustainable [14]. Kuratko and Morris [15] explain the various domains of SE and the forms that it can take. They refer to it as a range of innovative activities adopted by entrepreneurs to overcome the comparative disadvantage of the firms. Likewise, SE has been recognised as “a unique form of strategy in which a firm realizes sustainable competitive advantage does not rest upon any single source of competency; rather, sustainable competitive advantage depends upon a firm’s ability to develop a stream of continuous innovation to stay ahead of competitors” [16]. Such initiatives necessitate the allocation of resources to jointly seek new prospects and utilise today’s global marketplaces. Sustainability initiatives require the effective implementation of organisational capabilities, which can be achieved by having SE orientation in place [17]. Ferreira et al. [18] explore the barriers in business faced by non-management-degree-holding students. They reveal that obtaining financial support and high patent costs are the main barriers to an entrepreneur. They suggest that government and private investors should encourage potential entrepreneurs by providing funds. Similarly, from the rural Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) perspective, Fanelli [19] shows that a lack of financial support, technical incentives, and institutional support are major barriers that SMEs encounter. Shirokova [20] explores the relationship between SMEs’ performance during the economic crisis and the various components of SE such as entrepreneurial orientation, competitive advantage, managing resources strategically, and innovation in the context of Russia. The author finds that components of SE are directly related to the performance of the SMEs. It is evident from the above discussion that most of the studies are focused on SE and one or two barriers to SE adoption, and a comprehensive list of barriers is missing from the existing literature. In addition, some studies focus on the link between SE and the performance of the organisation and do not address the implementation aspect of SE. Further, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, the interrelationship among the barriers is not explored in the existing literature. Therefore, this study was conducted to fill this gap in the literature by focusing on the adoption aspect of SE as organisations face several barriers while they are trying to adopt SE. Then, the broad objective of this research is to identify the substantial barriers of SE and develop the causal relationship among them. The specific objectives of the study are as follows:

- Identifying significant barriers of SE adoption;

- Understanding the causal relationship between the barriers;

- Providing recommendations for the mitigation of these barriers.

To accomplish the research objectives, a comprehensive review of the literature was carried out to identify the barriers to SE, which were confirmed by a panel of experts. Finally, DEMATEL was applied to develop the causal interrelationship among the barriers.

The present study significantly contributes to the SE literature and has practical implications for SE development. The study identified barriers in SE that are in the nascent stage in the entrepreneurship and knowledge management literature. Moreover, understanding the barriers is helpful for policymakers to design development strategies, and can help business development managers’ successive planning of the organisation. Further, the study examines the causal relationship among the barriers, which provides an understanding of the nature of these barriers in terms of the drivers of other barriers or driven by other barriers according to expert opinion, which can be food for thought for managers of specific interventions in SE promotion. In addition, the present study provides the basic framework for a comprehensive primary-data-based study.

The rest of the paper is organised as follows: Section 2 deals with the background of the study; Section 3 discusses the applied methodology; Section 4 addresses the analysis and provides the result; Section 5 discusses the result, and implications are provided in Section 6; and the conclusion, limitations, and future scope are presented in Section 7.

2. Review of the Literature

SE is considered a scientific theory under the idea of strategic management and entrepreneurship [2]. SE is concerned with the simultaneous presentation of opportunity-seeking and advantage-seeking behaviours that ultimately result in greater value for individuals, organisations, and society [2]. SE can be considered an extension of the definition of entrepreneurial strategy formulation, which is the integration of various strategies with the external environment. It is based on two fundamental tenets: the formulation and execution of strategy require entrepreneurial ideas, such as vigilance, creativity, and judgment; and opportunity-seeking (the central subject of entrepreneurship) and advantage-seeking (the central subject of strategic management) behaviours should be viewed collectively. Strategic management involves strategic thinking and strategic planning, which provide a firm vision to search and plan for new resources [21]. Entrepreneurship is a “creative destruction” process in which innovation deconstructs current institutions to uncover and exploit prospects, talents, and resources that are employed distinctively as a means of intellectual wealth [21,22]. Ketchen et al. [23] described combining strategy and entrepreneurship domains, striking a balance between opportunity-seeking and advantage-seeking activities; an appropriate managerial mindset within the firm and the continuous innovation of either product or process have become the main pillars of SE. Hitt et al. [2] described the approach of integrating entrepreneurial and strategic perspectives that create wealth as SE. Mazzei [24] described it as a conceptual domain in which decision-makers in organisations explore the creative potential of multifaceted dynamics in a methodical fashion. SE fosters a dynamic approach that bolsters sustainable business growth through the integration of innovative and optimising strategies. SE has a broader scope than other forms of entrepreneurship, and addresses all kinds of performance enhancements and is not limited to financial aspects [25]. However, the concept of SE is not exhaustively explored in the literature of entrepreneurship and knowledge management.

Some of the pertinent research on SE includes work by Siadat and Naeiji [9], who identified the key components and dimensions of SE and used factor analysis to examine its characteristics. Their findings demonstrated that the competitiveness of knowledge-based organisations is positively impacted by the opportunity-based attitude, proactive behaviour, risk-taking behaviour, and constant innovation and value creation. The performance of a corporation and several aspects of SE were investigated by Shirokova et al. [20]. SMEs’ performance during the economic crisis was primarily examined in relation to their entrepreneurial attitude, innovation, strategic resource management, and competitive advantage. A framework was developed by Siddiqui and Jan [26] for the evaluation of SE in female-owned businesses in India. They found that innovativeness, networking, smart resource management, entrepreneurial culture and leadership, and entrepreneurial mindset all had an impact on SE. The most important factors were determined and entrepreneurial difficulties assessed using the Analytical Network Process (ANP) [27]. Using DANP (DEMATEL-ANP), many tourist entrepreneurship policy criteria have been prioritised in earlier studies [28].

Sriboonlue [29] investigated the association between business performance and SE awareness and developed a conceptual model using data from Thai SMEs. In the context of Iranian entrepreneurs, Gerard and Ghazi [30] investigated the various characteristics of SE. They found entrepreneurial innovation, growth and profitability, mindset towards entrepreneurship, capital mobilisation, and management and leadership to be the key dimensions. Entrepreneurship culture in South Asian countries is not significantly present due to the inadequately educated workforces, thus, it is considered an obstacle to entrepreneurship. Khan et al. [31] identified twelve barriers related to SE and modelled these barriers using ISM in the Indian context.

SE is the amalgamation of strategic management and entrepreneurship, and the present business environment requires this strategic entrepreneurial orientation. Entrepreneurial activities help discover new challenges and possibilities and strategic management ensures exceptional efficiencies. This combination helps maintain and enhance firms while also adding value to their sustainability [32]. The main objective of SE is to develop a competitive edge [33]. There is a wide range of internal and external barriers in the context of firms that hamper the growth of enterprises [34]. Simsek et al. [35] concluded the new directions of SE, suggesting that SE requires a common framework of definition and characteristics. Further, they emphasise that a clear understanding of potential and opportunities in SE is essential. Chaturvedi and Karri [36] mapped the barriers to entrepreneurship during the COVID-19 pandemic and found them to be organisational readiness, government support, inadequate technology, and finance. Jan and Anwar [37] discussed SE orientation for women-owned enterprises. The noticeable finding of the study is that strategic leadership of any kind does not have any role in SE. Soomro and Shah [38] argued that SE has significant implications for the financial and non-financial performance of firms. Networking, organisational learning, and collaborative innovation are the three main dimensions of SE [23]. Very few studies have been conducted in the area of SE in the context of developing and emerging economies [39]. The primary data from Cafe Business in Ambon, Kempa and Setiawan [40] suggest that entrepreneurial orientation has significant implications for SE, which further leads to competitive advantage. Yu et al. [41] in their bibliometric review of SE, showed that research progress in the field of SE is dynamic, yet there is room for researchers to provide clarity on definitions, models, facilitators, and inhibitors. Discussion on concepts like competitive advantage, strategies to help maintain market position, and barriers to entry is necessary for navigating and succeeding in challenging business environments [42]. Hence it becomes necessary to address the lack of literature on barriers to SE.

3. Methodology

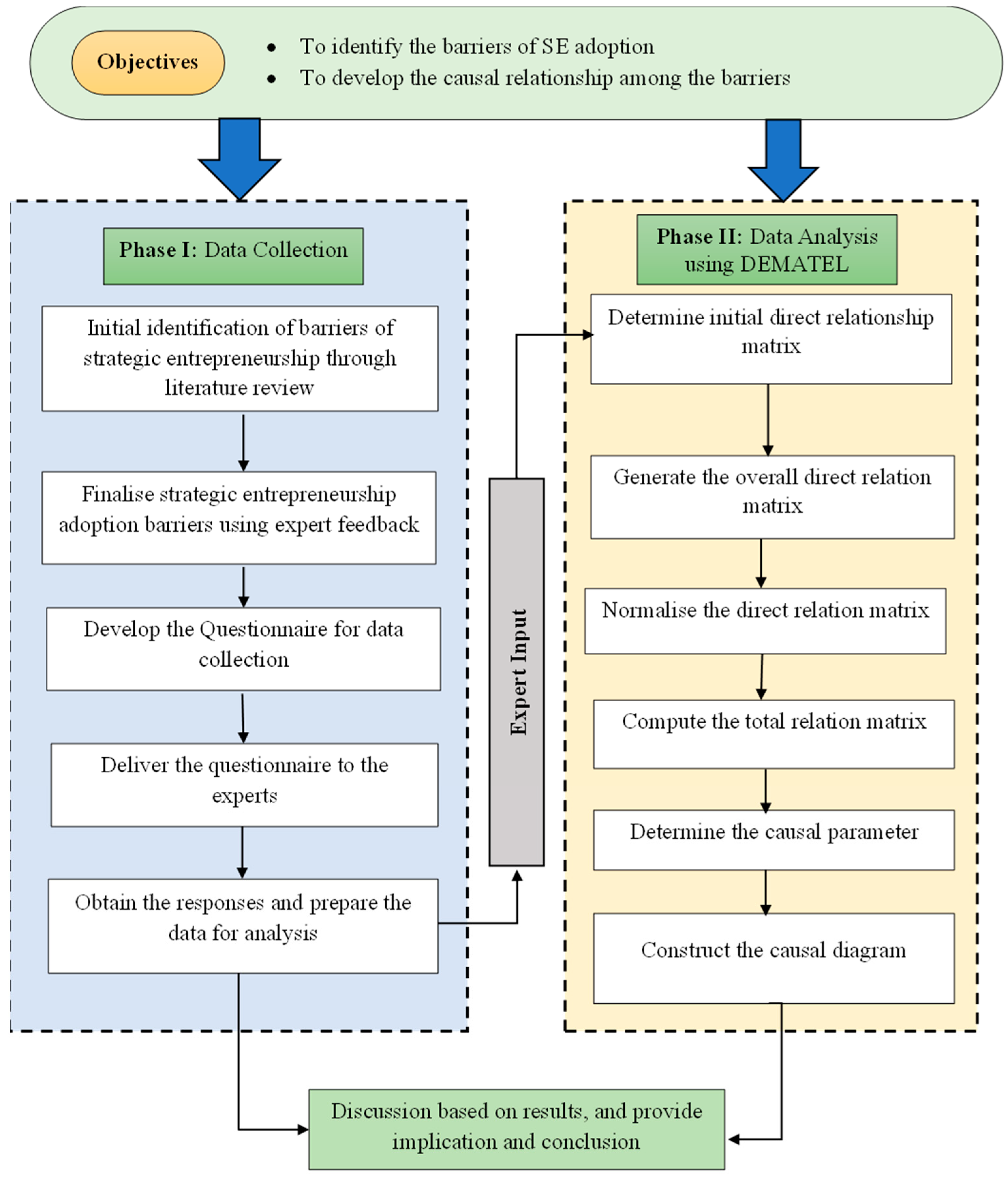

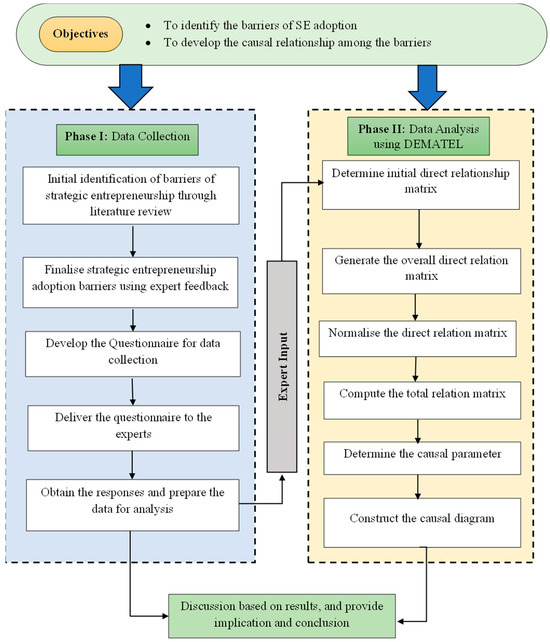

In order to achieve the above-mentioned objectives, a two-phase research methodology was used, as shown in Figure 1. The first phase deals with the identification of the barriers related to the adoption of the SE. To do this, we reviewed the relevant literature, mainly from Scopus, which is one of the largest databases of scholarly articles. Initially, a pool of barriers was identified and provided to the expert for feedback and finalisation.

Figure 1.

Conceptual research framework.

In the second phase, the interrelationship among the finalised barriers is identified. Several methods are available in the literature to identify the causal relationship, such as Interpretative Structural Modelling (ISM), Total Interpretative Structural Modelling (TISM), Weighted-Influence Non-linear Gauge System (WINGS), and DEMATEL [43,44]. These approaches have some drawbacks, particularly TISM and ISM [45]. For example, the strength of the quantitative relationships and interrelationships among the barriers cannot be ascertained using the ISM and TISM method [46,47]. For this reason, it is preferable to investigate the causal relationships between the finalised barriers using DEMATEL. Tsai et al. [43] and Yazo-Cabuya et al. [48] describe the DEMATEL approach as a decision-making strategy that relies on paired comparisons. This approach, which is component-based and micro-focused, may be used to analyse and make decisions in complex systems [46,49]. Therefore, it can ascertain the degree of barriers’ direct and indirect linkages. The interactions between barriers may be transformed using this method into a structural model of the entire system that can be divided into groups based on causes and effects. DEMATEL has been applied in the following areas: supply chain management traceability management [50], circular economy management [51], food supply chain management [52], tourism entrepreneurship [28], supplier selection [53], sustainable production [54], traceability adoption [50], innovation strategy development [55], circular economy [51], and remanufacturing [31].

DEMATEL

DEMATEL was created in 1976 as a tool for determining the causal relationship between variables [56]. The detailed steps of the DEMATEL technique are as follows:

- Step 1: Develop the direct influence matrix

An expert panel was formed and their feedback was utilised for the development of a direct influence matrix. These experts assessed the relative importance of different barriers of SE using a structured questionnaire. As mentioned in Table 1, the impact of barrier “i” over “j” was measured using a scale ranging from 0 to 4.

Table 1.

Linguistic scale for influential score.

Each expert provides their feedback in the form of a direct influence matrix [Xh] that is represented through Equation (1).

The element of the direct influence matrix is xijk represents the effect of barrier “i” on barrier “j”. The [Xh] is used to construct an n × n matrix for every expert, where h represents the hth expert (1 ≤ h ≤ k). Consequently, k experts generate k matrices indicated by the letters X1, X2, X3… Xk.

- Step 2: Construct an overall direct relation matrix

Using the direct influence matrix obtained from h experts, an overall direct relationship matrix is formed, and then the average matrix A = [aij] is derived using Equation (2).

- Step 3: Create the normalised direct relation matrix

From Equations (3) and (4), construct a normalised initial direct relation matrix

where

D = A· S

- Step 4: Calculate the total relation matrix

Develop the total relation matrix “T” using Equation (5)

where “I” represents the identity matrix.

- Step 5: Determine the causal parameters

Calculate the causal parameters with Equations (6) and (7):

where Ri signifies the row-wise summation and Cj implies the column-wise summation.

- Step 6: Determine the prominence and effect score

The prominence and effect score is calculated from Equations (8) and (9):

Pi = Ri +Ci

Ei = Ri − Ci

The prominence score (Pi) signifies the degree of net influence barriers i that contribute to the system, whereas the impact score (Ei) shows the amount of net influence barriers that “i” detracts from the system. If the effect score (Ei = Ri − Ci) is greater than zero, barrier “i” is considered as a cause; otherwise, it belongs to the effect group. Based on these values the causal diagram is developed, the prominence score is displayed on the x-axis and the effect score on the y-axis.

4. Results

This section presents the process of identification of the barriers to SE adoption followed by the DEMATEL analysis, which provides an understanding of the causal interrelationship among the barriers of SE.

4.1. Barriers to SE Adoption

The literature review of the relevant articles helps to identify the early adoption barriers for SE. The articles were obtained from Scopus-indexed journals only, using keywords such as “SE”, “barriers”, and “strategic innovation”. Additionally, the combinations of these keywords were searched for the article selection using a Boolean operator. Scopus is the biggest database that offers a broad range of reviews of academic and non-academic literature across numerous sectors [57,58]. One advantage of Scopus over WoS is that it loads over 70% more sources than WoS [59]. Therefore, it ensures the quality of the literature reviewed. Thereafter, an intensive review was carried out of the selected articles to explore the initial list of barriers to the adoption of SE. Further, an expert group of five members was formed: four from industry and one from academia. The selected experts have worked for more than 10 years in their respective areas. Details about the experts are provided in Appendix A. After the expert panel formation, the identified barriers list containing twelve barriers was given to the expert group members, and their comments were taken. They suggested the elimination of two factors (working culture and lack of stakeholder support) as they do not find these to be sufficiently related to SE, while ten barriers to the adoption of SE were kept for further analysis. These are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Barriers to SE adoption.

4.2. DEMATEL Analysis

The causal interrelationships among the barriers to SE adoption were developed using DEMATEL. To effectively implement the DEMATEL method, a brief overview of DEMATEL was provided to the experts. Further, the experts were asked to provide feedback in terms of the influence of one barrier on others using the five-point linguistic scale in the initial relation matrix (IRM). In this manner, five IRM matrices were generated (see Appendix B). These matrices were transformed into an overall direct relationship matrix (DRM) using Equations (1) and (2), and are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

The overall direct relationship matrix (A).

Further, Equations (3) and (4) were used to transform the DRM into a normalised direct relation matrix (NRM). The NRM of the identified barriers is shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Normalised direct relation matrix (D).

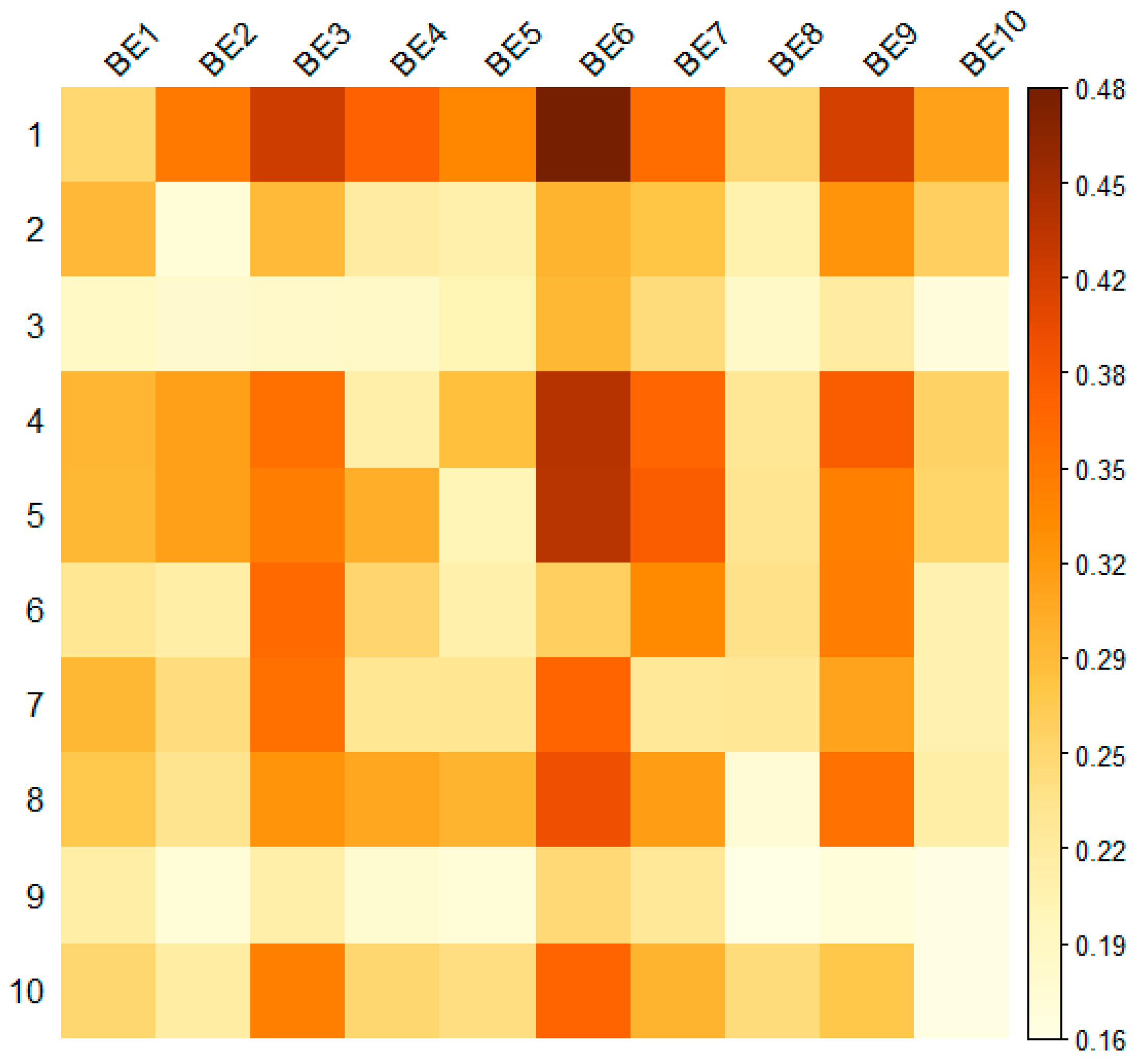

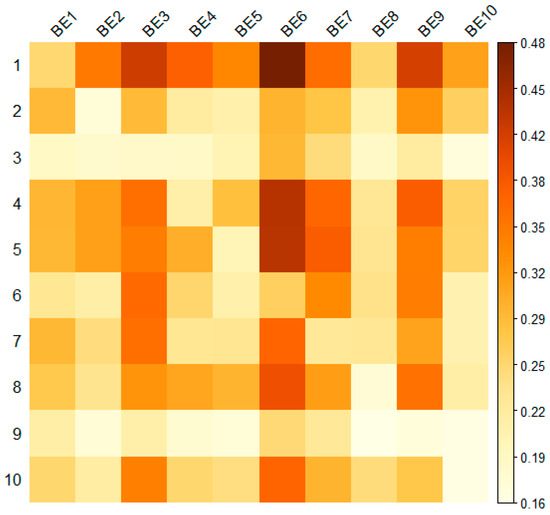

After that, Equation (5) was used to transform this NRM into a total relation matrix (TRM), as illustrated in Table 5. This matrix shows the influence of one barrier on another, and the same is represented by the heat map shown in Figure 2.

Table 5.

The total relation matrix (T).

Figure 2.

Heat map for T matrix.

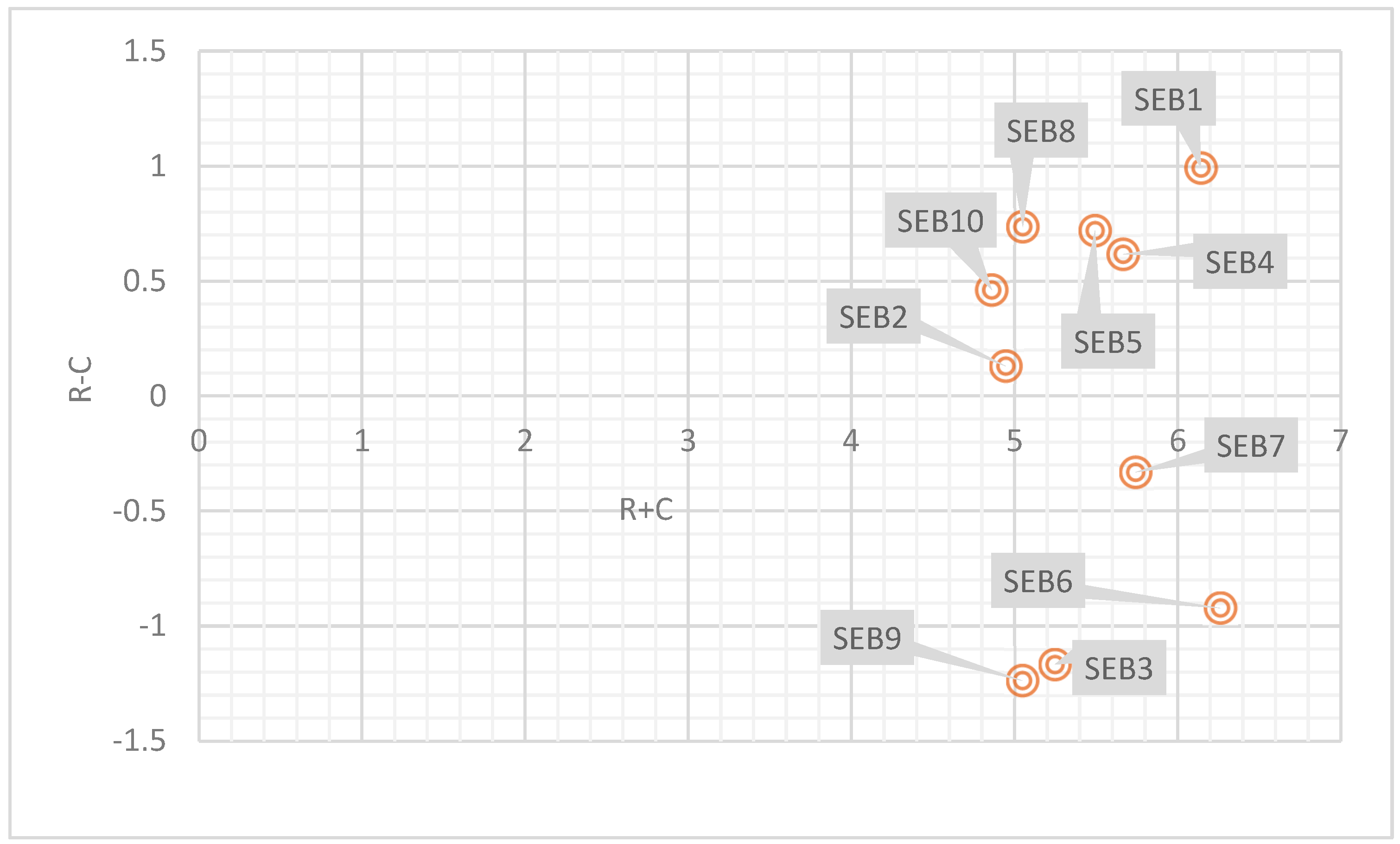

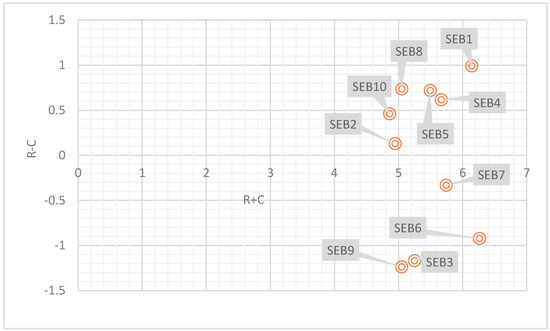

The causal parameters were calculated using the total relation matrix value. TRM’s row-wise summation (using Equation (6)) is denoted by , while its column-wise summation (using Equation (7)) is denoted by . The prominence () and net effect () were calculated using Equations (8) and (9). The causal parameters are shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Cause and effect of barriers to adopting SE.

When () is positive, the barrier is seen as influential; otherwise, it is regarded as influencing. The barrier is separated into a cause and effect group based on the value of (). The prominence vector () is displayed horizontally, whereas the net effect vector () is presented vertically. Figure 3 depicts the development of the causal network diagram.

Figure 3.

Cause and effect diagram for the barriers to SE adoption.

4.3. Sensitivity Analysis

This section presents sensitivity analyses to assess the performance of the applied method and the impact of potential changes in the results under various conditions. As DEMATEL heavily relies on the opinions of experts, depending on the opinions of each expert, a sensitivity analysis was carried out to determine the influence of input data on the conclusions, and a scenario-based analysis was produced by altering the importance of the experts [72]. To do this, a scenario-based approach was applied to explore potential modifications to the outcomes under various scenarios with varying expert opinion weighting. Five scenarios were developed for this purpose, with an expert being preferred in each situation. The preferred experts were weighted as 0.6 and the remaining experts were kept uniform at 0.1. In this manner, five different scenarios were created and are shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Expert importance in five different scenarios.

After applying the DEMATEL to the final scenarios and obtaining the influence and influential score, the results of the scenario-based DEMATEL were obtained and are presented in Table 8. The results of the sensitivity analysis show that the cause and effect barriers are the same in each scenario. This infers that the results are reliable and considered to be less affected by the experts’ biases. It also noted that low awareness of SE is the most influential barrier of the four scenarios among the five scenarios, and less networking is the most influenced barrier of all five scenarios. This indicates that the solution is stable and one can rely on the ranking of the barriers.

Table 8.

Sensitivity analysis for five different scenarios.

5. Discussion

A summary of the DEMATEL result is shown in Figure 3. As shown in Table 6, the values indicate the relative importance of each barrier. As a result, those with higher () values are taken into account. The importance order of each barrier based on the are limited innovation’ low awareness of SE’ lack of exploiting opportunities’ lack of entrepreneurial mindset’ low financial support’ lack of strategic management’ risk aversion’ less networking’ deficiency of entrepreneurial culture’ business models’. As per the value of , the most important barriers are limited innovation, low awareness about SE, and lack of exploiting opportunities. These barriers need to be mitigated on a priority basis to implement the SE.

The DEMATEL analysis also categorised the barriers into the cause and effect group. The entire system is affected by cause group barriers, and the ultimate goals are influenced by performance. As a result, additional attention is required, since () values are positive, indicating that the influencing impact () is bigger than the influenced impact (). The six barriers obtained in the cause group were ‘low awareness of SE’, risk aversion’, low financial support’, lack of entrepreneurial mindset’, business models’, and ‘deficiency of entrepreneurial culture’. These barriers need urgent attention from the management so that SE can be adopted in the organisation. Among the cause group barriers, low awareness of SE’ is the biggest barrier to the adoption of strategic entrepreneurship. These findings are in line with those of Suong and Dien [73] and Chang and Wang [74]. In the context of Vietnam, Suong and Dien [73] also found that a lack of awareness of strategic entrepreneurship is a major barrier to its adoption. Due to a lack of awareness, entrepreneurs may not find strategic entrepreneurship very lucrative [21]. Since strategic entrepreneurial methods may not be perceived as valued or distinct from conventional approaches, organisations and individuals may be reluctant to implement them [2]. The awareness can be developed through workshops and seminars that lead to the development of an entrepreneurial culture. AlQershi [75] demonstrated how businesses with more entrepreneurially minded people and resources might benefit from uncertainty. The organisation’s “risk-averse attitude”, which impedes SE implementation, is the next significant barrier. The explanation for this might be that it discourages businesses and workers from accepting uncertainty, considering alternative solutions, and learning lessons from mistakes [76,77,78]. Growth and innovation are hindered by this risk aversion, which makes it difficult to pursue innovative ideas and adapt to changing market conditions [79,80,81]. A risk-averse attitude has significant importance related to innovation; the attitude should be risk-seeking rather than risk-averse. Risk-taking is a key aspect of entrepreneurship and a crucial indicator of SE, and reflects an SME’s willingness to take risks through new product development and exploring new market opportunities [82]. Research shows that firms that embrace a moderate level of risk-taking perform significantly better than those who choose very low risk-taking levels [83]. The next barrier is low financial support, which creates a barrier to the adoption of SE. Finn and Walters [84] also concluded that a lack of funding and implementation capacity problems are two barriers poor countries face when trying to implement strategic entrepreneurship. The adoption of strategic entrepreneurship may be hampered by inadequate funding because of the negative consequences it has on long-term sustainability, risk appetite, expansion, and competitiveness. Management needs to be able to provide financial support for innovation. The government should focus on sustainable entrepreneurship development to remove this barrier.

Another barrier to the adoption of SE is a lack of an entrepreneurial mindset. Through increasing knowledge of SE within the organisation, this entrepreneurial attitude may be fostered. Kuratko et al., [85] found that one of the potential barriers to the implementation of strategic entrepreneurship in organisations may be the absence of encouragement and support for innovative endeavours. Empirical evidence suggests that in order for businesses to create meaningful added value, managers and staff alike need to adopt an entrepreneurial attitude [86]. Similar to our findings, Matarazzo et al. [87] research on Italian SMEs demonstrates that a strategic entrepreneurial attitude significantly raises the value of entrepreneurship, offering advantages and additional value to individuals. Furthermore, the adoption of SE is hampered by the current business model. SE relies on innovation, which is difficult given the constraints of the current business model. The absence of an entrepreneurial culture, which is crucial for SE to be adopted successfully, is the next major barrier. According to Ferreira et al. [88], creating an entrepreneurial culture is essential to resource development and may be accomplished by managers and organisation members successfully exchanging knowledge. Since SE involves the interdependence of product, process, marketing, and organisational features, creating an innovative culture is crucial to its implementation [89].

The remaining four barriers obtained in the effect group are lack of exploiting opportunities, limited innovation, lack of strategic management, and less networking. Mensah and Dadzie [90] found that the main obstacle to entrepreneurship among young people is a lack of market opportunities. A lack of possibilities limits a strategic entrepreneur’s ability to innovate, grow, and exploit market advantages, which reduces their chances of success and sustainability. The potential of emerging market companies to engage in strategic entrepreneurship is restricted by resource constraints [91]. Strategic entrepreneurs are hindered in their efforts to differentiate their offerings, adapt to market shifts, and create sustainable competitive advantages when there is limited innovation [92,93]. The results of this study are consistent with Foss and Lyngsie [94], emphasising the value of utilising human resource expertise to spot and capture opportunities that will support sustaining competitive advantage. Furthermore, companies might strategically utilise innovation to create novel or improved products, services, and procedures, thus acquiring a competitive edge in reaction to outside shifts [95]. Farida et al. [14], advocate that strategic management promotes entrepreneurial skills and aids in challenging conventional capabilities. Hattar et al. [96] conducted a study on SMEs in Jordan and showed that entrepreneurial networks help in obtaining outside knowledge and can be used to develop internal capabilities. These barriers are influenced by the cause group barriers, so this could be mitigated by removing the cause group barriers. As the cause group barriers are mitigated, these barriers are also reduced [97]. Therefore, management needs to focus on cause group barriers first in order to adopt SE.

6. Implications

The result shows that low awareness of SE, risk aversion, and low financial support are the most significant barriers. These barriers need the immediate attention of management, government, and policy planners for mitigation. This implies that if an organisation focuses on removing these barriers, SE will be more effective. As a result, through organising awareness programmes and seminars, the understanding of SE among working staff and management can be improved. Further, financial assistance for SE should be provided, and this might be achieved by allocating a reasonable amount of funds for SE. This study also confirms that SE faces several barriers related to management and working personnel, and these need to be mitigated systematically.

7. Conclusions

This study deals with the adoption of SE by exploring the barriers associated with its adoption. In order to conduct this study, a comprehensive literature review was conducted to identify the barriers related to the adoption of SE. These barriers were finalised through the experts’ input by considering the current relevance. The ten finalised barriers were modelled using the DEMATEL method. The DEMATEL analysis categorised these barriers into two groups: cause and effect. The cause group contained six barriers, namely, low awareness of SE, risk aversion, low financial support, lack of entrepreneurial mindset, business models, and deficiency of entrepreneurial culture. These barriers need to be highly prioritised for the successful adoption of SE. The remaining four barriers belong to the effect group, namely, lack of exploiting opportunities, limited innovation, lack of strategic management, and less networking. The outcome of this research may help organisations to adopt SE.

The limitations of this research are highlighted here so the findings can be interpreted correctly. The first limitation is that the identification of the barriers was carried out through the available literature, which appears to be constrained. As a result, there is a possibility that some substantial barriers to SE will go ignored. Another problem might be that the DEMATEL is based on expert opinion, which could be biased. These constraints can be resolved by using a large sample size of experts and along with a systematic literature review. Furthermore, the fuzzy integration with the chosen approach helps to eliminate subjectivity and bias in the experts’ contribution.

This research might be expanded in several ways. Advanced modelling tools, such as Structural Equation Modelling (SEM), can be used to develop the relationship among the identified barriers. The priority of the barriers can also be determined through analytic hierarchy process (AHP), analytic network process (ANP), proximity indexed value (PIV), and best–worst method (BWM) approaches in future studies. The result of this study can be validated through case studies in upcoming research. Further, to improve the reliability of the chosen barriers, the WoS database can be used in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.K. and N.F.; Methodology, N.F.; Software, S.K.; Validation, S.S.A. and D.N.; Formal analysis, S.K.; Investigation, S.K., N.F. and A.D.; Resources, S.S.A.; Data curation, S.K.; Writing–original draft, S.K. and N.F.; Writing–review & editing, S.S.A. and A.D.; Visualization, A.D. and D.N.; Supervision, S.S.A.; Project administration, S.S.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Experts’ Profiles.

Table A1.

Experts’ Profiles.

| Expert | Qualifications | Position | Experience | Firm Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expert 1 | Master of Business Administration | General manager | 15 years | Medium |

| Expert 2 | M.Sc. in Management | Operations manager | 18 years | Small |

| Expert 3 | Master of Business Administration | Corporate relations manager | 12 years | Medium |

| Expert 4 | PhD | Professor | 20 years | Academic institute |

| Expert 5 | Master of Technology | R&D Head | 14 years | Small |

Appendix B. Experts’ Responses

Table A2.

Expert 1 Response.

Table A2.

Expert 1 Response.

| Barriers | SEB1 | SEB2 | SEB3 | SEB4 | SEB5 | SEB6 | SEB7 | SEB8 | SEB9 | SEB10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEB1 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| SEB2 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| SEB3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| SEB4 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| SEB5 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| SEB6 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 |

| SEB7 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| SEB8 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| SEB9 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| SEB10 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

Table A3.

Expert 2 Response.

Table A3.

Expert 2 Response.

| Barriers | SEB1 | SEB2 | SEB3 | SEB4 | SEB5 | SEB6 | SEB7 | SEB8 | SEB9 | SEB10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEB1 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| SEB2 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| SEB3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| SEB4 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| SEB5 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| SEB6 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 |

| SEB7 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| SEB8 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| SEB9 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| SEB10 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

Table A4.

Expert 3 Response.

Table A4.

Expert 3 Response.

| Barriers | SEB1 | SEB2 | SEB3 | SEB4 | SEB5 | SEB6 | SEB7 | SEB8 | SEB9 | SEB10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEB1 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| SEB2 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| SEB3 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| SEB4 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| SEB5 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| SEB6 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 2 |

| SEB7 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| SEB8 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 2 |

| SEB9 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| SEB10 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 0 |

Table A5.

Expert 4 Response.

Table A5.

Expert 4 Response.

| Barriers | SEB1 | SEB2 | SEB3 | SEB4 | SEB5 | SEB6 | SEB7 | SEB8 | SEB9 | SEB10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEB1 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 4 |

| SEB2 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 |

| SEB3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| SEB4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 2 |

| SEB5 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| SEB6 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 |

| SEB7 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| SEB8 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 1 |

| SEB9 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| SEB10 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 0 |

Table A6.

Expert 5 Response.

Table A6.

Expert 5 Response.

| Barriers | SEB1 | SEB2 | SEB3 | SEB4 | SEB5 | SEB6 | SEB7 | SEB8 | SEB9 | SEB10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEB1 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| SEB2 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| SEB3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| SEB4 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| SEB5 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| SEB6 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| SEB7 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| SEB8 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| SEB9 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| SEB10 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

References

- Xin, B.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, W.; Lou, C.X.; Shee, H.K. Strategic entrepreneurship and Sustainable Supply Chain Innovation from the perspective of collaborative advantage. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitt, M.A.; Ireland, R.D.; Camp, S.M.; Sexton, D.L. Strategic entrepreneurship: Entrepreneurial strategies for wealth creation. Strateg. Manag. J. 2001, 22, 479–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suriyankietkaew, S.; Phallapa, P.A. Retrospective and Foresight: Bibliometric Review of International Research on Strategic Management for Sustainability, 1991–2019. Sustainability 2019, 12, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleimani, M.; Mollaei, E.; Beinabaj, M.H.; Salamzadeh, A. Evaluating the enablers of Green Entrepreneurship in Circular Economy: Organizational Enablers in focus. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ireland, R.; Covin, J.; Kuratko, D. Conceptualizing Corporate Entrepreneurship Strategy. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 19–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ireland, R.D.; Hitt, M.A. Achieving and maintaining strategic competitiveness in the 21st century: The role of strategic leadership. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 1999, 13, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farjoun, M. Towards an organic perspective on strategy. Strateg. Manag. J. 2002, 23, 561–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D.; Lehmann, E.; Plummer, L. Agency and Governance in Strategic Entrepreneurship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siadat, S.; Naeiji, M. Developing a measurement for strategic entrepreneurship by linking its dimensions to competitiveness in knowledge-based firms. Int. J. Bus. Innov. Res. 2019, 18, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaian, A.; Naeiji, M.J. Intellectual capital and strategic entrepreneurship as determinants of organizational performance: Empirical evidence from Iran steel industry. J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2011, 1, 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, J. Corporate Entrepreneurship: A Strategic and Structural Perspective. In International Council for Small Business, Proceedings of the 47th World Conference, San Juan, Puerto Rico, 28 June 2002; Academy of International Business: East Lansing, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Zhou, R.; Zhou, Y. Analysis of critical factors for the entrepreneurship in industries of the future based on DEMATEL-ISM approach. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, J.; Winsor, B. Socio-cultural barriers to developing a regional entrepreneurial ecosystem. J. Enterprising Communities People Places Glob. Econ. 2019, 13, 263–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farida, F.A.; Hermanto, Y.B.; Paulus, A.L.; Leylasari, H.T. Strategic Entrepreneurship Mindset, Strategic Entrepreneurship Leadership, and entrepreneurial value creation of smes in East Java, Indonesia: A strategic entrepreneurship perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuratko, D.F.; Morris, M.H. Corporate entrepreneurship: A critical challenge for educators and researchers. Entrep. Educ. Pedagog. 2018, 1, 42–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, J.W.; Ketchen, D.J.; Ireland, R.D. Strategic entrepreneurship within family-controlled firms: Opportunities and challenges. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2010, 1, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albhirat, M.M.; Zulkiffli, S.N.; Salleh, H.S.; Zaki, N.A. A study on strategic entrepreneurship orientations: Indicators, differential pathways, and multiple business sustainability outcomes. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2023, 18, 1625–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.; Paço, A.; Raposo, M.; Hadjichristodoulou, C.; Marouchou, D. International entrepreneurship education: Barriers versus support mechanisms to STEM students. J. Int. Entrep. 2021, 19, 130–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanelli, R.M. Barriers to adopting new technologies within rural small and medium enterprises (SMEs). Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirokova, G.; Ivvonen, L.; Gafforova, E. Strategic entrepreneurship in Russia during economic crisis. Foresight STI Gov. 2019, 13, 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuratko, D.F.; Audretsch, D.B. Strategic entrepreneurship: Exploring different perspectives of an emerging concept. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, S.A.; Venkataraman, S. The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketchen, D.J., Jr.; Ireland, R.D.; Snow, C.C. Strategic entrepreneurship, collaborative innovation, and wealth creation. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2007, 1, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzei, M. Strategic entrepreneurship: Content, process, context, and outcomes. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2018, 14, 657–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyver, M.; Lu, T.-J. Sustaining innovation performance in smes: Exploring the roles of strategic entrepreneurship and it capabilities. Sustainability 2018, 10, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, S.; Jan, S. Developing and Validating a Scale to Assess Strategic Entrepreneurship Among Women: A Case of Jammu and Kashmir in India. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2019, 20, 387–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalilsanjani, A.; Saparauskas, J.; Yazdani-Chamzini, A.; Turskis, Z.; Feyzbakhsh, A. Developing a model based on sustainable development for prioritizing entrepreneurial challenges under a competitive environment. J. Compet. 2021, 13, 73–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari-Moghadam, S.; Zali, M.R.; Sanaeepour, H. Tourism entrepreneurship policy: A hybrid MCDM model combining DEMATEL and ANP (DANP). Decis. Sci. Lett. 2017, 6, 233–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriboonlue, P. Strategic Entrepreneurial Awareness and Business Performance: Empirical Evidence from Small and Medium-sized Enterprises in Thailand. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2019, 158, 653–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerard, P.; Ghazi, E. Strategic entrepreneurship element from theory to practice. Int. J. Bus. Technopreneurship 2014, 4, 205–219. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S.; Ali, S.; Singh, R. Determinants of Remanufacturing Adoption for Circular Economy: A Causal Relationship Evaluation Framework. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2022, 5, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, M.; Stephens, S.; Md Fadzil, A.F. Sustainability in family business settings: A strategic entrepreneurship perspective. J. Fam. Bus. Manag. 2024. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tülüce, N.S.; Yurtkur, A.K. Term of strategic entrepreneurship and Schumpeter’s creative destruction theory. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 207, 720–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremml, T. Barriers to entrepreneurship in public enterprises: Boards contributing to inertia. Public Manag. Rev. 2021, 23, 1527–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simsek, Z.; Heavey, C.; Fox, B.C. (Meta-) framing strategic entrepreneurship. Strateg. Organ. 2017, 15, 504–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, R.; Karri, A. Entrepreneurship in the times of pandemic: Barriers and strategies. FIIB Bus. Rev. 2022, 11, 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, S.; Anwar, A. Strategic entrepreneurship in light of entrepreneurial and strategic orientations: A case of women entrepreneurs of Jammu and Kashmir in India. J. Public Aff. 2021, 22, e2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soomro, B.A.; Shah, N. Entrepreneurial orientation and performance in a developing country: Strategic entrepreneurship as a mediator. Bus. Strategy Dev. 2020, 3, 567–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantur, D. Strategic entrepreneurship: Mediating the entrepreneurial orientation-performance link. Manag. Decis. 2016, 54, 24–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempa, S.; Setiawan, T.G. The Effect of Entrepreneurial Orientation on the Competitive Advantage through Strategic Entrepreneurship in the Cafe Business in Ambon. Int. J. Bus. Stud. 2019, 2, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Qin, Y.; Xu, Z.; Škare, M. Bibliometric analysis of Strategic Entrepreneurship Literature. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2022, 18, 1475–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyhani, M. The logic of strategic entrepreneurship. Strateg. Organ. 2023, 21, 460–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, J.-F.; Wu, S.-C.; Kathinthong, P.; Tran, T.-H.; Lin, M.-H. Electric vehicle adoption barriers in Thailand. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keleş Tayşir, N.; Ülgen, B.; İyigün, N.Ö.; Görener, A. A framework to overcome barriers to social entrepreneurship using a Combined Fuzzy MCDM approach. Soft Comput. 2023, 28, 2325–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Luthra, S.; Garg, D. Internet of things (IoT) based coordination system in Agri-food supply chain: Development of an efficient framework using DEMATEL-ISM. Oper. Manag. Res. 2020, 15, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakeri, H.; Khalilzadeh, M. Analysis of factors affecting project communications with a hybrid DEMATEL-ISM approach (A case study in Iran). Heliyon 2020, 6, e04430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mondal, S.; Singh, S.; Gupta, H. Green Entrepreneurship and digitalization enabling the circular economy through Sustainable Waste Management—An exploratory study of emerging economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 422, 138433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazo-Cabuya, E.J.; Herrera-Cuartas, J.A.; Ibeas, A. Organizational Risk Prioritization using DEMATEL and AHP towards Sustainability. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makki, A.A.; Al-Filali, I.Y. Modeling the strategic enablers of financial sustainability in Saudi higher education institutions using an integrated decision-making trial and Evaluation Laboratory–Interpretive Structural Modeling Approach. Sustainability 2024, 16, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haleem, A.; Khan, S.; Khan, M. Traceability implementation in food supply chain: A grey-DEMATEL approach. Inf. Process. Agric. 2019, 6, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Haleem, A. Strategies to Implement Circular Economy Practices: A Fuzzy DEMATEL Approach. J. Ind. Integr. Manag. 2020, 5, 253–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sufiyan, M.; Haleem, A.; Khan, S.; Khan, M. Evaluating food supply chain performance using hybrid fuzzy MCDM technique. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2019, 20, 40–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakoç, Ö.; Memiş, S.; Sennaroglu, B. A review of sustainable supplier selection with decision-making methods from 2018 to 2022. Sustainability 2023, 16, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, K.-K.; Lin, S.-W.; Lo, H.-W.; Hsiao, C.-Y.; Lai, P.-J. Risk assessment in sustainable production: Utilizing a hybrid evaluation model to identify the waste factors in steel plate manufacturing. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, S.-F.; Horng, J.-S.; Liu, C.-H.; Lin, J.-Y. Innovation strategy development and facilitation of an integrative process with an MCDM framework. Entrep. Res. J. 2021, 13, 935–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Haleem, A.; Khan, M.; Abidi, M.; Al-Ahmari, A. Implementing Traceability Systems in Specific Supply Chain Management (SCM) through Critical Success Factors (CSFs). Sustainability 2018, 10, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shareefa, M.; Moosa, V. The Most-Cited Educational Research Publications on Differentiated Instruction: A Bibliometric Analysis. Eur. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 9, 331–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranckutė, R. Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus: The titans of bibliographic information in today’s academic world. Publications 2021, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Illescas, C.; de Moya-Anegón, F.; Moed, H.F. Coverage and citation impact of oncological journals in the Web of Science and Scopus. J. Informetr. 2008, 2, 304–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luke, B.; Verreynne, M. Exploring strategic entrepreneurship in the public sector. Qual. Res. Account. Manag. 2006, 3, 4–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ireland, R.; Hitt, M.; Sirmon, D. A Model of Strategic Entrepreneurship: The Construct and its Dimensions. J. Manag. 2003, 29, 963–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danish, R.; Asghar, J.; Ahmad, Z.; Ali, H. Factors affecting “entrepreneurial culture”: The mediating role of creativity. J. Innov. Entrep. 2019, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyrgidou, L.; Petridou, E. The effect of competence exploration and competence exploitation on strategic entrepreneurship. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2011, 23, 697–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Walker, E.; Redmond, J. Explaining the lack of strategic planning in SMEs: The importance of owner motivation. Int. J. Organ. Behav. 2007, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Neneh, N. An exploratory study on entrepreneurial mindset in the small and medium enterprise (SME) sector: A South African perspective on fostering small and medium enterprise (SME) success. S. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2012, 6, 3364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, R. Toward a knowledge-based theory of the firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 1996, 17, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, H. Entrepreneurship development and financial literacy in Africa. World J. Entrep. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 11, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lounsbury, M.; Cornelissen, J.; Granqvist, N.; Grodal, S. Culture, innovation and entrepreneurship. Innovation 2018, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ireland, R.; Webb, J. Strategic entrepreneurship: Creating competitive advantage through streams of innovation. Bus. Horiz. 2007, 50, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuckertz, A.; Kollmann, T.; Krell, P.; Stöckmann, C. Understanding, differentiating, and measuring opportunity recognition and opportunity exploitation. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2017, 23, 78–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, L.; Rindova, V.; Greenbaum, B. Unlocking the Hidden Value of Concepts: A Cognitive Approach to Business Model Innovation. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2015, 9, 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torkayesh, A.E.; Hendiani, S.; Walther, G.; Venghaus, S. Fueling the future: Overcoming the barriers to market development of renewable fuels in Germany using a novel analytical approach. Eur. J. Oper. Res 2024, 316, 1012–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suong, H.T.T.; Dien, H.T. Entrepreneuship Barriers, A Case Study of Small and Medium Enterprises in some Typical Sectors, Evidence from Vietnam. Rev. Geintec-Gest. Inov. E Tecnol. 2021, 11, 1298–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.J.; Wang, H.B. A Case Study on the Model of Strategic Entrepreneurship. Int. J. Organ. Innov. 2013, 5, 30–44. [Google Scholar]

- AlQershi, N. Strategic thinking, strategic planning, Strategic Innovation and the performance of smes: The mediating role of human capital. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2021, 11, 1003–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapepa, O.; van Vuuren, J. The importance of tolerance for failure and risk-taking among insurance firms in hyperinflationary Zimbabwe. S. Afr. J. Entrep. Small Bus. Manag. 2019, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manso, G. Creating incentives for innovation. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2017, 60, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, A.H. Strategic dimensions of maintenance management. J. Qual. Maint. Eng. 2002, 8, 7–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brocas, I.; Carrillo, J.D.; Giga, A.; Zapatero, F. Risk aversion in a dynamic asset allocation experiment. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 2019, 54, 2209–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arundel, A. Rethinking the effect of risk aversion on the benefits of service innovations in public administration agencies. Res. Policy 2017, 46, 900–910. [Google Scholar]

- Osiyevskyy, O.; Dewald, J. Inducements, impediments, and immediacy: Exploring the cognitive drivers of small business managers’ intentions to adopt business model change. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2015, 53, 1011–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meekaewkunchorn, N.; Szczepańska-Woszczyna, K.; Muangmee, C.; Kassakorn, N.; Khalid, B. Entrepreneurial orientation and SME Performance: The mediating role of learning orientation. Econ. Sociol. 2021, 14, 294–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satar, M.S.; Natasha, S. Individual social entrepreneurship orientation: Towards development of a measurement scale. Asia Pac. J. Innov. Entrep. 2019, 13, 49–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, B.; Walters, J. Workshop report–Public transport markets in development. Res. Transp. Econ. 2010, 29, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuratko, D.F.; Hornsby, J.S.; McKelvie, A. Entrepreneurial mindset in corporate entrepreneurship: Forms, impediments, and actions for research. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2023, 61, 132–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, B.S.; Eshima, Y.; Hornsby, J.S. Strategic entrepreneurial behaviors: Construct and scale development. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2018, 13, 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matarazzo, M.; Penco, L.; Profumo, G.; Quaglia, R. Digital transformation and customer value creation in made in Italy smes: A dynamic capabilities perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 123, 642–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.J.; Ratten, V.; Dana, L.-P. Knowledge spillover-based strategic entrepreneurship. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2016, 13, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, H.K. Establishing an innovation culture and strategic entrepreneurship. In Global Business Strategies in Crisis: Strategic Thinking and Development; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 169–184. [Google Scholar]

- Mensah, A.C.; Dadzie, J. Application of Principal Component Analysis on Perceived Barriers to Youth Entrepreneurship. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2020, 9, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lien, Y.C.; Hsu, C.W.; Chen, H. Strategic Entrepreneurship and Controlling Family Effect. In Academy of Management Proceedings; Academy of Management: Briarcliff Manor, NY, USA, 2014; Volume 2014, p. 13117. [Google Scholar]

- Canare, T.; Francisco, J.P. Does Competition Enhance or Hinder Innovation? J. Southeast Asian Econ. 2021, 38, 24–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicen, P.; Johnson, W.H.; Zhu, Z. The Role of Lean Innovation Capability in Resource-Limited Innovation: Concept, Measurement, and Consequences: An Abstract. In Finding New Ways to Engage and Satisfy Global Customers: Proceedings of the 2018 Academy of Marketing Science (AMS) World Marketing Congress (WMC); Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 849–850. [Google Scholar]

- Foss, N.J.; Lyngsie, J. The emerging strategic entrepreneurship field: Origins, key tenets, and research gaps. In Handbook of Organizational Entrepreneurship; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2011; Available online: http://ssrn.com/paper=1747711 (accessed on 14 May 2024).

- Deslatte, A.; Swann, W.L. Elucidating the linkages between entrepreneurial orientation and local government sustainability performance. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2019, 50, 92–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattar, C.; Batista, L.; Mansour, H.; Fakoussa, R. The role of sustainability-oriented innovation in food supply chain: A perspective of HR managers. In Proceedings of the 7th International EurOMA Sustainable Operations and Supply Chain Forum, Nottingham, UK, 10–12 February 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S.; Fatma, N.; Khan, M.I.; Haleem, A. Modelling of Barriers Towards the Adoption of Strategic Entrepreneurship: An Indian Context. In Contextual Strategic Entrepreneurship; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 35–55. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).