Ecological Legacies and Ethnotourism: Bridging Science and Community in Ecuador’s Amazonia

Abstract

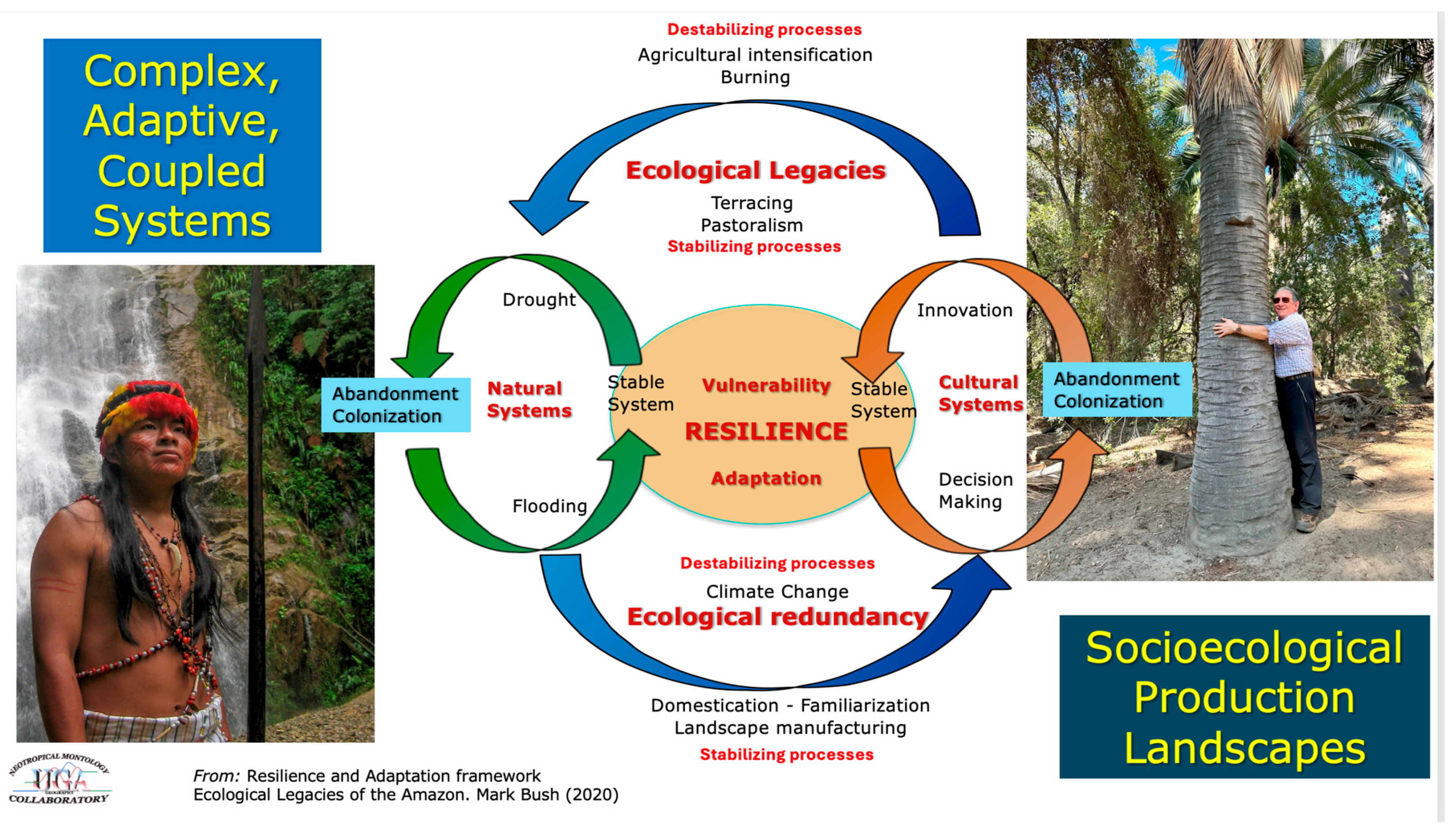

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methods of Bridging Science and Community Stewardship

2.2. Ecological Legacies of the Amazon and Ecotourism

2.3. Eco-Ethnotourism in Amazonia

2.4. Upper Amazonia and Tourism of Cultural Mountainscapes

3. Results

4. Discussion

“Hay que entrar a las comunidades con la actitud de pares, reconociendo el conocimiento ancestral y el conocimiento científico. Hay que depositar la información y no sólo extraerla” [We must enter the communities with the attitude of peers, recognizing ancestral knowledge and scientific knowledge. Information must be deposited and not just extracted]

“Las atrocidades de los conquistadores deben concientizarse, ¡pero hay que mirar hacia adelante! Nosotros somos una descendencia originaria y la mayoría; se debe respetar la cultura, nuestra música, nuestra gastronomía y ponderarla para que a nivel internacional llegue el mensaje de nuestras bellezas” [Conquerors’ atrocities must be acknowledged, but we must look forward! We are original descendants and the majority; We must respect the culture, our music, our gastronomy and praise it so that the message of our beauties reaches the international level].

“Habrá que confabular la innovación con lo de antaño. Para ponderar al mundo la belleza de la Amazonía. El secreto es el respeto de las etnias y los conocimientos ancestrales. Hay que reclamar y sostener la identidad amazónica” [Innovation will have to be combined with the old. To show the world the beauty of the Amazon. The secret is respect for ethnic groups and ancestral knowledge. We must reclaim and sustain the Amazonian identity].

“Debería ser que la objetivación de los miembros de la comunidad termine. Somos sujetos, no objetos. Se tiene que cuidar del concepto de etnoturismo, que debería tener una ordenanza de política pública desde el gobierno, y las unidades de desarrollo deben beneficiarse de la. inversión turística. No hay que hacer elefantes blancos para compensar el daño ambiental de las petroleras y mineras en la selva” [It should be that the objectification of community members ends. We are subjects, not objects. The concept of ethnotourism must be taken care of, which should have a public policy ordinance from the government, and the development units must benefit from it. tourism investment. There is no need to create white elephants to compensate for the environmental damage of oil and mining companies in the jungle].

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. The Kuk’a Umawa Declaration for Bridging Science and Ethnotourism

- That the Higher Polytechnic School of Chimborazo (ESPOCH) Orellana Campus, the Pan-American Center for Geographic Studies and Research (CEPEIGE), and the Neotropical Montology Collaboratory of the University of Georgia (UGA) have organized a successful international workshop on Ecological Legacies and Ethnotourism: Nexus between Community and Science.

- That the participants representing the points of view of Amazonian, national, and foreign universities, as well as of the original peoples’ communities located in the Napo River basin of western upper Amazonia, identified the need to join efforts between scientists and communities.

- That there is an urgent need to find alternate decolonial models, allowing for transdisciplinary scientific activity that favors inclusion of ancestral knowledge and ending objectification of local researchers and community scholars as mere informants, imperative in this time of global environmental change.

- That inventories of flora and fauna be complemented with linguistic records of the communities to maintain the lists of species with vernacular names and that new species that are being discovered receive the appropriate binomial nomenclature naming the species with the vernacular territorial name or of the community that owns that biocultural element.

- That scientific research is segmented by short-term financing, hence when the financing ends, the generated science ends. This hiatus implies the needed activation of museums, herbariums, insectariums, serpentariums, university organizations, and civil society organizations, supporting long-term scientific activity.

- That the influence of the prevailing religion (i.e., Catholic, Evangelical, etc.) has penetrated ancestral practices and rituals, and is a sign of accelerated acculturation tendencies of some groups that assume it to satisfy the visitor curiosity, instead of invigorating shamanism, with local animism and vernacular literacy. In addition, the religious division generated between missioners of foreign cults sometimes caused violent crashes in the local communities (e.g., between the Enomenga Waorani in the Dícaro community and the Iromenga Waorani in the Toñanpade community).

- That the future of tropandean forests in the Andean–Amazonian flanks depends on the sustainability and regeneration of cultural landscapes, considering them from a montological, integrative, and transdisciplinary perspective, for which it is necessary to prioritize geoethnotourism operations over mining exploitation activities and ecotourism that focus only on the fauna and flora of the Amazon Hylea and not on its custodians, and in many cases its creators of the domesticated and manufactured “garden jungle” of yesteryears.

- To make joint efforts to favor the hybridity of Amazonian culture and nature and thus maintain the ecological legacy of the original peoples who survived with their traditional knowledge and vernacular descriptors that explain, according to ancestral science and their habitual practices, the cohabitation of non-human entities with humans.

- To advocate for improving the dissemination of traditional and Indigenous knowledge in a multicultural way, so that scientists who come to study the jungle put aside elitist feelings and superiority of scientific studies on vernacular literacy, the jungle worldview, and ways of accessing it, to share knowledge through shared methodologies and results, both in its planning and in its execution and subsequent publication.

- To require researchers be able to communicate in the national language (Ecuadorian Spanish) and, preferably, in the local language of native nationalities of these territories (e.g., a’ingae—Kofán; paicoca—Siona dialect; sikopai—Secoya dialect; waotededo and waotidido—Sabela, Guikita, Tiweno and Aushiri dialects; Chicham or šiwar’a—Shwar, Shiwiar, and Achwar dialects); and kichwa—Amazonian (or Eastern) dialect. Whenever possible, researchers must have international approval for research on human subjects and sign the ethical code of the International Society for Ethnobiology that requires both prior and informed knowledge and consent of the communities, as well as the equitable distribution of the results of the research, be it intellectual, academic, professional, or commercial and industrial.

- To insist on creating research stations in productive socioecological landscapes in which the communities become custodians of the jungle and administrators of the facilities for long-term research whose financing guarantees continuation of basic and applied research, as well as the monitoring of environmental conditions in socioenvironmental aspects of protected cultural landscapes, especially in iconic trees, food supplies, memory reserves, sacred sites, landscape reserves, Indigenous territories, literary reserves, and biocultural reserves and micro-refuges of biodiversity and cultural and linguistic diversity.

- To recognize the persistence of knowledge and the will of the people who are in the territory. The country’s legal and legislative frameworks must be integrated into the disciplinary curricula of universities so that they have a more authentic interculturality. There must be motivation of foreign researchers to expand and facilitate the process of integration of knowledge and the formation of local expert knowledge, be it from grade school to postgraduate degrees, or from the oral history of local scholars who can be non-Western science teachers of researchers who come from abroad.

- To demand that the Andean–Amazon flank’s schools teach content required by the national curriculum, but in the languages and dialects of the area, with trained presential (face-to-face) instructors who teach kichwa of the Amazon—not kichwa from the mountains—or who teach radiophonic schools in kichwa not only in Shwar, favoring distance education with online, virtual connections.

- To promote the integration of elements of modernity without prejudice to maintaining the Indigenous identity by crafting religious syncretism and strengthening the transmission of ancestral knowledge in a proud revival of interculturality and intergenerational transmission of knowledge from the elderly and older adults in their non-school special education and vernacular literacy.

- To insist on the need for these types of workshops and seminars that integrate ecological legacies and geoethnotourism to be replicated in many other Amazonian sites, so that the local authorities in charge of managing GADs and government institutions value and prioritize the integration of communities and scientists.

- To promote and demand that the Law of Planning for the Special Circumscription of the Amazon Territory with respect to gender equality, preferred employment, environmental protection, and wise use of natural resources be observed. Also, that the Fund for Sustainable Development of Amazonia (FDSA) and the Common Fund (FC) coordinated by the Amazonian Technical Secretariat serve to augment the collaborative activities of scientific research and ethnotourism in the Amazonian decentralized, autonomous governments, including administrators, scientists, and community members working on those territories.

- To prevent economic powers from prevailing over the ecological powers of the Amazonian cultural landscape by limiting extractive actions (e.g., illegal mining, drilling, and oil exploration activities in protected areas, biopiracy, and abuse of native practices for folklorized tourism purposes, disguising their authenticity to please ephemeral visitors).

- To enter communities with the attitude of peers, recognizing the collaborative effort between ancestral knowledge and scientific knowledge, and thereby depositing the information and not just extracting it without local benefit or published record of intellectual authorship of the research.

- To confabulate innovation with ancestral practice, to ponder to the world the beauty of the Amazon generated by the jungle gardeners, the domestication and familiarization of the biota in the Pan-Amazon ancient and modern cultural landscape and the Andean–Amazon flanks.

- To show respect for the ethnic group and the ancestral knowledge that they still cherish. It is necessary to reclaim and sustain the Amazonian identity, eliminating features that ‘folklorize’ identity markers such as hammocks, necklaces, earrings, ribbons, chigras, tattoos of various colors and symmetries that reflect origin and affiliation instead of a mere ornament attractive to tourists.

- To become aware of atrocities of the “conquest” that must be analyzed not only in their historical but also moral and ethical frameworks. But we must look ahead. We are of original descent and most mestizos and foreigners respect the culture of the jungle, including music, gastronomy, art, and legends. We must weigh the message of our endangered beauties, preventing them from getting lost in the maelstrom of globalization. In doing so, we must recover the valuation of characters, geographical landmarks, civic dates of nationalities and erect monuments to these indicators instead of the “conquerors” or “discoverers”.

- To pay for communities’ instruction in their quest to defend their ethnicity and financing sustainable and regenerative development of native peoples, since they are a treasured legacy and they do not have access to the available facilities. Therefore, to ask the public powers and the corresponding private, civil groups to then carry out the diverse, equitable, and inclusive scientific advancement with a pan-Amazonian inspiration.

- To eliminate the idea of the community as an “object” and to integrate it as a “subject” of science with considerations of convergent and integrative montology. To seek that the concept of geoethnotourism has a public policy ordinance. The government and regional development units should benefit from the investment, not as white elephants but as proactive action units for the conservation of biocultural heritage.

- Given in the city of Coca, Ecuador, in the auditorium of the Orellana headquarters of ESPOCH campus, on Saturday, 20 May 2023, on behalf of the workshop participants,

| Fausto Sarmiento, Ph.D. | Renato Chávez, Ph.D.(c) | Nelson Ortega, M.Sc |

| CMN_UGA–CMS_IGU | ESPOCH | CEPEIGE |

Appendix B. The Tabulation of Results and Visualization of Values from the Survey of Ecological Legacies and Ethnotourism: The Link between Community and Science

- -

- The response options were not appropriate.

- -

- The questions should be more understandable

- -

- Is it important to know the vernacular names of places in the Amazon?

- -

- Should the province of Orellana be called in honor of the conquistador yes or no?

- -

- Does it matter what we are and what we will do in the face of global warming?

- -

- Do you think it is important that the communities can relate to the students in the form of mutual teaching?

- -

- What do you act or how do you help the forest to conserve it, research is done, but many times it does not help to conserve and save it from mining?

- -

- How can you encourage society to take an interest in such an important topic?

References

- Rice, W.L.; Mateer, T.J.; Reigner, N.; Newman, P.; Lawhon, B.; Taff, B.D. Changes in Recreational Behaviors of Outdoor Enthusiasts during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Analysis across Urban and Rural Communities. J. Urban Ecol. 2020, 6, juaa020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, V.L. Hosts and Guests: The Anthropology of Tourism; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Clements, C.R. Agrobiodiversity in Amazonia. In Encyclopedia of Biodiversity, 3rd ed.; Scheiner, S.M., Ed.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2024; Volume 4, pp. 228–238. ISBN 978-0-323-98434-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Gugerli, K. How Ethnotourism Exoticizes Latin America’s Indigenous Peoples. Available online: https://panoramas.secure.pitt.edu/health-and-society/how-ethnotourism-exoticizes-latin-americas-indigenous-peoples#:~:text=By%20using%20traditional%20dress%20and,for%20traveling%20Americans%20and%20Europeans (accessed on 22 April 2024).

- Davidov, V.M.D. Shamans and Shams: The Discursive Effects of Ethnotourism in Ecuador. J. Lat. Am. Caribb. Anthropol. 2010, 15, 387–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marris, E. Rambunctious Garden: Saving Nature in a Post-Wild World; Bloomsbury Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Laso, F. Galapagos Is a Garden; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 137–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huertas López, T.E.; Pilco Segovia, E.A.; Suárez García, E.; Salgado Cruz, M.; Jiménez Valero, B.; Huertas López, T.E.; Pilco Segovia, E.A.; Suárez García, E.; Salgado Cruz, M.; Jiménez Valero, B. Acercamiento Conceptual Acerca de Las Modalidades Del Turismo y Sus Nuevos Enfoques. Rev. Univ. Y Soc. 2020, 12, 70–81. [Google Scholar]

- Bush, M.B.; McMichael, C.N.H. Holocene Variability of an Amazonian Hyperdominant. J. Ecol. 2016, 104, 1370–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levis, C.; Costa, F.R.C.; Bongers, F.; Peña-Claros, M.; Clement, C.R.; Junqueira, A.B.; Neves, E.G.; Tamanaha, E.K.; Figueiredo, F.O.G.; Salomão, R.P.; et al. Persistent Effects of Pre-Columbian Plant Domestication on Amazonian Forest Composition. Science 2017, 355, 925–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damasco, G.; Baraloto, C.; Vicentini, A.; Daly, D.C.; Baldwin, B.G.; Fine, P.V.A. Revisiting the Hyperdominance of Neotropical Tree Species under a Taxonomic, Functional and Evolutionary Perspective. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 9585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stronza, A.L.; Hunt, C.A.; Fitzgerald, L.A. Ecotourism for Conservation? Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2019, 44, 229–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, E.; Castriota, R. Urbanismos Tropicails, cadernos de campo. Estud. Avançados 2024, 29, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guattari, F. The Three Ecologies; Bloomsbury Publishing: Camden, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sarmiento, F.O.; Ibarra, J.T.; Barreau, A.; Pizarro, J.C.; Rozzi, R.; González, J.A.; Frolich, L.M. Applied Montology Using Critical Biogeography in the Andes. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2017, 107, 416–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chazdon, R.L. Tropical Forest Recovery: Legacies of Human Impact and Natural Disturbances. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2003, 6, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saqalli, M.; Béguet, E.; Maestripieri, N.; de Garine, E.; Saqalli, M.; Béguet, E.; Maestripieri, N.; Garine, E.D. “Somos Amazonia,” a New Inter-Indigenous Identity in the Ecuadorian Amazonia: Beyond a Tacit Jus Aplidia of Ecological Origin? Perspect. Geográfica 2020, 25, 12–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terborgh, J. Bird Species Diversity on an Andean Elevational Gradient. Ecology 1977, 58, 1007–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, A.; Beresford-Jones, D.G.; Heggarty, P. Rethinking the Andes Amazonia Divide: A Cross-Disciplinary Exploration; UCL Press: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myster, R. The Andean Cloud Forest; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, C.C. 1491: New Revelations of the Americas before Columbus; Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Denevan, W.M. The “Pristine Myth” Revisited. Geogr. Rev. 2011, 101, 576–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, J.; Gardner, T.A.; Lees, A.C.; Parry, L.; Peres, C.A. How Pristine Are Tropical Forests? An Ecological Perspective on the Pre-Columbian Human Footprint in Amazonia and Implications for Contemporary Conservation. Biol. Conserv. 2012, 151, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balee, W. Cultural Forests of the Amazon: A Historical Ecology of People and Their Landscapes; University of Alabama Press: Tuscaloosa, AL, USA, 2013; pp. 1–268. [Google Scholar]

- Sarmiento, F.; Sarmiento, E. 2021-Flancos Andinos: Paleoecología, Biogeografía Crítica y Ecología Política En Los Climas Cambiantes de Los Bosques Neotropicales de Montaña; Instituto de Investigación para el Desarrollo Sustentable de la Ceja de Montaña, Universidad Nacional Toribio Rodríguez de Mendoza de Amazonas: Chachapoyas, Perú, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostain, S.; Dorison, A.; de Saulieu, G.; Prümers, H.; Le Pennec, J.-L.; Mejia, F.; Freire, A.; Pagán-Jiménez, J.; Descola, P. Two Thousand Years of Garden Urbanism in the Upper Amazon. Science 2024, 383, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuggle, S. Impure and Worldly Geography: Pierre Gourou and Tropicality by Gavin Bowd and Daniel Clayton (Review). Fr. Stud. A Q. Rev. 2020, 74, 335–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, A. The Ultimate “Other”: Post-Colonialism and Alexander Von Humboldt’s Ecological Relationship with Nature. Hist. Theory 2003, 42, 111–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Castro, E.V. Images of Nature and Society in Amazonian Ethnology. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 1996, 25, 179–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Londoño Sulkin, C.D. Moral Sources and the Reproduction of the Amazonian Package. Curr. Anthropol. 2017, 58, 477–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ter Steege, H.; Pitman, N.; Sabatier, D.; Baraloto, C.; Salomão, R.; Guevara Andino, J.; Phillips, O.; Castilho, C.; Magnusson, W.; Molino, J.-F.; et al. Hyperdominance in the Amazonian Tree Flora. Science 2013, 342, 1243092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T. Crude Desires and “Green” Initiatives: Indigenous Development and Oil Extraction in Amazonian Ecuador. In The Ecotourism-Extraction Nexus: Political Economics and Rural Realities of (Un)comfortable Bedfellows; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piperno, D.R.; McMichael, C.N.H.; Bush, M.B. Finding Forest Management in Prehistoric Amazonia. Anthropocene 2019, 26, 100211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morcote-Ríos, G.; Aceituno, F.; Iriarte, J.; Robinson, M.; Chaparro-Cárdenas, J. Colonisation and Early Peopling of the Colombian Amazon during the Late Pleistocene and the Early Holocene: New Evidence from La Serranía La Lindosa. Quat. Int. 2020, 578, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, E.G. The Heart of Lightness. In Engaging Archaeology; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaulicke, P. Early Social Complexity in Northern Peru and Its Amazonian Connections; University College London: London, UK, 2020; pp. 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, M.B. New and Repeating Tipping Points: The Interplay of Fire, Climate Change, and Deforestation in Neotropical Ecosystems1. Ann. Mo. Bot. Gard. 2020, 105, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMichael, C.N.H.; Vink, V.; Heijink, B.M.; Witteveen, N.H.; Piperno, D.R.; Gosling, W.D.; Bush, M.B. Ecological Legacies of Past Fire and Human Activity in a Panamanian Forest. Plants People Planet 2023, 5, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento, F.O.; Rodríguez, J.; Yepez-Noboa, A. Forest Transformation in the Wake of Colonization: The Quijos Andean Amazonian Flank, Past and Present. Forests 2022, 13, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yépez-Noboa, A. Conviviendo Con Volcanes Catastróficos al Este de Los Andes Ecuatoriales. In Wege im Garten der Ethnologie: Zwischen dort und hier. Festchrift für María Susana Cipolleti; Anthropos Institut, Ed.; Academia Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2013; pp. 383–401. [Google Scholar]

- Bush, M.B.; Silman, M.R.; McMichael, C.; Saatchi, S. Fire, Climate Change and Biodiversity in Amazonia: A Late-Holocene Perspective. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond B Biol. Sci. 2008, 363, 1795–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rostain, S. Between Sierra and Selva: Landscape Transformations in Upper Ecuadorian Amazonia. Quat. Int. 2012, 249, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åkesson, C.M.; McMichael, C.N.H.; Raczka, M.F.; Huisman, S.N.; Palmeira, M.; Vogel, J.; Neill, D.; Veizaj, J.; Bush, M.B. Long-Term Ecological Legacies in Western Amazonia. J. Ecol. 2021, 109, 432–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoms, M.C.; Fraser, A.W.; Wise, R.M. Chapter 1—Riverine Landscapes and Resilience. In Resilience and Riverine Landscapes; Thoms, M., Fuller, I., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazmiño, E.M. Monumentality and Social Complexity in the Upano Valley, Upper Amazon of Ecuador. In The Archaeology of the Upper Amazon: Complexity and Interaction in the Andean Tropical Forest; Clasby, R., Nesbitt, J., Eds.; University Press of Florida: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2021; pp. 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo-Kalin, M.; Panduro, S. La Arqueología Del Río Napo: Noticias Recientes y Desafíos Futuros. Rev. Del Mus. De La Plata 2019, 4, 331–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balee, W.; Swanson, T.; Benavides, M.; Macedo, J. Evidence for Landscape Transformation of Ridgetop Forests in Amazonian Ecuador. Lat. Am. Antiq. 2023, 34, 842–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christoffersen, L. Amazonian Erasures: Landscape and Myth-Making in Lowland Bolivia. Rural. Landsc. Soc. Environ. Hist. 2018, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furquim, L.; Neves, E.; Shock, M.; Watling, J. The Constructed Biodiversity, Forest Management and Use of Fire in Ancient Amazon: An Archaeological Testimony on the Last 14,000 Years of Indigenous History; Springer: Singapore, 2023; pp. 259–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lins, J.; Lima, H.P.; Baccaro, F.B.; Kinupp, V.F.; Jr, G.H.S.; Clement, C.R. Pre-Columbian Floristic Legacies in Modern Homegardens of Central Amazonia. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0127067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bush, M.B.; McMichael, C.H.; Piperno, D.R.; Silman, M.R.; Barlow, J.; Peres, C.A.; Power, M.; Palace, M.W. Anthropogenic Influence on Amazonian Forests in Pre-History: An Ecological Perspective. J. Biogeogr. 2015, 42, 2277–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groom, M.J.; Podolsky, R.D.; Munn, C.A. Tourism as a Sustained Use of Wildlife: A Case Study of Madre de Dios, Southeastern Peru; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Stronza, A. “Because It Is Ours”: Community-Based Ecotourism in the Peruvian Amazon; University of Florid: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, D.W.; Hendrickson, T.; Castillo, A. Ecotourism and Conservation in Amazonian Perú: Short-Term and Long-Term Challenges. Environ. Conserv. 1997, 24, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, C.A.; Munn, C.A. Macaw Biology and Ecotourism, or “When a Bird in the Bush Is Worth Two in the Hand”. In New World Parrots in Crisis Solutions from Conservation Biology; Beissinger, S.R., Snyder, N.F.R., Eds.; Smithsonian Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA; London, UK, 1992; pp. 47–72. [Google Scholar]

- Gössling, S. Ecotourism: A Means to Safeguard Biodiversity and Ecosystem Functions? Ecol. Econ. 1999, 29, 303–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stronza, A. The Economic Promise of Ecotourism for Conservation. J. Ecotourism 2007, 6, 210–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcinek, A.; Hunt, C. Social Capital, Ecotourism, and Empowerment in Shiripuno, Ecuador. Int. J. Tour. Anthropol. 2015, 4, 327–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borman, R. Ecotourism and Conservation: The Cofan Experience. In Ecotourism and Conservation in the Americas; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2008; pp. 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.; Bilsborrow, R. A Cross-Cultural Analysis of Human Impacts on the Rainforest Environment in Ecuador. In Human Population; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; Volume 1650, pp. 127–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stronza, A.; Gordillo, J. Community Views of Ecotourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2008, 35, 448–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidov, V. Ecotourism and Cultural Production, An Anthropology of Indigenous Spaces in Ecuador; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; p. 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stronza, A. Hosts and Hosts: The Anthropology of Community-Based Ecotourism in the Peruvian Amazon. NAPA Bull. 2005, 23, 170–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stronza, A. Through a New Mirror: Reflections on Tourism and Identity in the Amazon. Hum. Organ. 2008, 67, 244–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stronza, A. Commons Management and Ecotourism: Ethnographic Evidence from the Amazon. Int. J. Commons 2010, 4, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doughty, C.; Lu, F.; Sorensen, M. Crude, Cash and Culture Change: The Huaorani of Amazonian Ecuador. Consilience 2010, 4, 18–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ojeda, D. Green Pretexts: Ecotourism, Neoliberal Conservation and Land Grabbing in Tayrona National Natural Park, Colombia. J. Peasant Stud. 2012, 39, 357–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, T.M. Sustainable Ecotourism in Amazonia: Evaluation of Six Sites in Southeastern Peru. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2013, 15, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunder, S. Ecotourism and Economic Incentives—An Empirical Approach. Ecol. Econ. 2000, 32, 465–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkby, C.A.; Giudice-Granados, R.; Day, B.; Turner, K.; Velarde-Andrade, L.M.; Dueñas-Dueñas, A.; Lara-Rivas, J.C.; Yu, D.W. The Market Triumph of Ecotourism: An Economic Investigation of the Private and Social Benefits of Competing Land Uses in the Peruvian Amazon. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e13015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adetutu, E.M.; Thorpe, K.; Bourne, S.; Cao, X.; Shahsavari, E.; Kirby, G.; Ball, A.S. Phylogenetic Diversity of Fungal Communities in Areas Accessible and Not Accessible to Tourists in Naracoorte Caves. Mycologia 2011, 103, 959–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, J.L.; Hill, R.A. Ecotourism in Amazonian Peru: Uniting Tourism, Conservation and Community Development. Geography 2011, 96, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernela, J.; Zanotti, L. Limits to Knowledge: Indigenous Peoples, NGOs, and the Moral Economy in the Eastern Amazon of Brazil. Conserv. Soc. 2014, 12, 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchins, F. Footprints in the Forest: Ecotourism and Altered Meanings in Ecuador’s Upper Amazon. J. Lat. Am. Caribb. Anthropol. 2007, 12, 75–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, E.M.; Mykletun, R.J. Guides as Contributors to Sustainable Tourism? A Case Study from the Amazon. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2012, 12, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanotti, L. Folk Knowledge, Interactive Learning, and Education: Community-Based Ecotourism in Amazon. Anthropol. Environ. Educ. 2012, 117–141. [Google Scholar]

- Fotiou, E. The Globalization of Ayahuasca Shamanism and the Erasure of Indigenous Shamanism. Anthropol. Conscious. 2016, 27, 151–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Mura, P.; Hall, C.; Fontaine, J. Spirituality, Drugs, and Tourism: Tourists’ and Shamans’ Experiences of Ayahuasca in Iquitos, Peru. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2016, 41, 314–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salibová, D. Ayahuasca Ethno-Tourism and Its Impact on the Indigenous Shuar Community (Ecuador) and Western Participants. Český Lid 2020, 107, 511–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavenská, V.; Simonová, H. Ayahuasca Tourism: Participants in Shamanic Rituals and Their Personality Styles, Motivation, Benefits and Risks. J. Psychoact. Drugs 2015, 47, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkelman, M. Drug Tourism or Spiritual Healing? Ayahuasca Seekers in Amazonia. J. Psychoact. Drugs 2005, 37, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarmiento, F.O.; Haller, A.; Marchant, C.; Yoshida, M.; Leigh, D.S.; Woosnam, K.; Porinchu, D.F.; Gandhi, K.; King, E.G.; Pistone, M.; et al. La Montología Global 4D: Hacia las Ciencias Convergentes y Transdisciplinarias de Montaña a través del Tiempo y el Espacio. Pirineos 2023, 178, e075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gow, P. An Amazonian Myth and Its History; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Rival, L. Huaorani Transformations in Twenty-First-Century Ecuador: Treks into the Future of Time; University of Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2016; p. 339. [Google Scholar]

- Wasserstrom, R. Surviving the Rubber Boom: Cofán and Siona Society in the Colombia-Ecuador Borderlands (1875–1955). Ethnohistory 2014, 61, 525–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haffer, J. Avian Species Richness in Tropical South America∗. Stud. Neotrop. Fauna Environ. 1990, 25, 157–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Robledo, C.; Kuprewicz, E.; Baer, C.; Clifton, E.; Hernández, G.; Wagner, D. The Erwin Equation of Biodiversity: From Little Steps to Quantum Leaps in the Discovery of Tropical Insect Diversity. Biotropica 2020, 52, 590–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMichael, C.N.H. Ecological Legacies of Past Human Activities in Amazonian Forests. New Phytol. 2021, 229, 2492–2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, C.L.; Bilsborrow, R.E.; Bremner, J.L.; Lu, F. Indigenous Land Use in the Ecuadorian Amazon: A Cross-Cultural and Multilevel Analysis. Hum. Ecol. 2008, 36, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cave, J.; Dredge, D. Regenerative Tourism Needs Diverse Economic Practices. In Global Tourism and COVID-19; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Adame, F. Meaningful Collaborations Can End ‘Helicopter Research’. Nature 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibarra, J.; Caviedes, J.; Marchant, C.; Mathez-Stiefel, S.-L.; Navarro-Manquilef, S.; Sarmiento, F. Mountain Social-Ecological Resilience Requires Transdisciplinarity with Indigenous and Local Worldviews. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2023, 38, 1005–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozzi, R.; Massardo, F.; Poole, A. The “3Hs” Of the Biocultural Ethic: A “Philosophical Lens” To Address Global Changes in the Anthropocene. In Global Changes: Ethics, Politics and Environment in the Contemporary Technological World; Valera, L., Castilla, J.C., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 153–170. [Google Scholar]

- Bellato, L.; Pollock, A. Regenerative Tourism: A State-of-the-Art Review. Tour. Geogr. 2023, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dredge, D. Regenerative Tourism: Transforming Mindsets, Systems and Practices. J. Tour. Futures 2022, 8, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayusada. Available online: https://wayusada.com/ (accessed on 16 May 2024).

| # | Research Priorities and Community Development | Ancestral Wisdom | Memory of Discovery | Ethnotourism Management |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Field coordination | Learning tools | Who discovered | Increase visitor numbers |

| 2 | Major players | Community access | Motives of discovery | Type of tourist experience |

| 3 | Community immersion | Access in elderly | Prior rubber booms | Class of tourist experience |

| 4 | Original language | Storytelling at home | Keeping chroniclers | Culture as experience |

| 5 | Publications in vernacular | Legends from father | Spanish version | Jungle as explanatory |

| 6 | Scientist whereabouts | Legends from mother | Ecuador is Amazonia | Difficult of translation |

| 7 | Knowledge of scientists | Schooling tradition | Richest exploitation | Assuming landscape fabric |

| 8 | Commoners’ whereabouts | Lost wisdom | Historical limits | Access to local knowledge |

| 9 | Knowledge of commoners | Using shamans | Catholic influence | Jungle lifescapes |

| 10 | Applying findings | Traditional medicine | Protestant influence | Culture management |

| 11 | Sharing knowledges | Keeping tradition | Lost cities tales | Harmonic study practice |

| 12 | Time length in relation | Applying wisdom | Jungle settlements | Children and youngsters |

| 13 | Transmission of wisdom | Loosing wisdom | Orellana’s example | Governmental support |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sarmiento, F.O.; Bush, M.B.; McMichael, C.N.H.; Chávez, C.R.; Cruz, J.F.; Rivas-Torres, G.; Kavoori, A.; Weatherford, J.; Hunt, C.A. Ecological Legacies and Ethnotourism: Bridging Science and Community in Ecuador’s Amazonia. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4664. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16114664

Sarmiento FO, Bush MB, McMichael CNH, Chávez CR, Cruz JF, Rivas-Torres G, Kavoori A, Weatherford J, Hunt CA. Ecological Legacies and Ethnotourism: Bridging Science and Community in Ecuador’s Amazonia. Sustainability. 2024; 16(11):4664. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16114664

Chicago/Turabian StyleSarmiento, Fausto O., Mark B. Bush, Crystal N. H. McMichael, C. Renato Chávez, Jhony F. Cruz, Gonzalo Rivas-Torres, Anandam Kavoori, John Weatherford, and Carter A. Hunt. 2024. "Ecological Legacies and Ethnotourism: Bridging Science and Community in Ecuador’s Amazonia" Sustainability 16, no. 11: 4664. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16114664