Abstract

In this research, we conducted 1 × 3 and 2 × 2 between-subject experiments to delve into the impacts of ESG assurance, the assurance presentation mode, and the depth of assured ESG indicators on the investment inclination of non-professional investors. Our empirical findings illuminated that non-professional investors exhibited a stronger inclination to invest in companies endorsed with ESG assurance compared to those lacking such endorsement. Furthermore, we observed that this inclination was heightened by presenting the ESG assurance report separately from the ESG report and by enriching the assured ESG indicators. Mediation analysis underscored that the influence of ESG assurance on the investment willingness of non-professional investors operated through its effect on their perception of companies’ ESG performances. This study stands as a valuable addition to the literature on non-financial information disclosure, shedding light on the pivotal role of ESG assurance.

1. Introduction

Sustainable development and environmental issues have received increasing attention in recent decades. Under this circumstance, the disclosure of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) information is crucial to the transformation of a sustainable global economy by integrating sustainable profitability with principles of social equity and environmental conservation. In response to this, an increasing number of global corporations include ESG disclosures to express their dedication to these issues and be responsible to a wide range of stakeholders.

Despite the growing prevalence of ESG reports, inconsistencies and gaps in these documents have hindered their effectiveness in enhancing public trust, as well as the perceived credibility and precision of the information presented. As noted by Sauerwald and Su (2019) [1], ESG reports are expected to convey credible and accurate information. Nevertheless, various studies have revealed discrepancies in the accuracy of these reports, potentially leading to distorted information for stakeholders [2,3]. A significant factor contributing to the misinformation in ESG reports is the practice of symbolic management, where managers often resort to deceptive practices by establishing organizational facades to convey specific signals [4,5]. Especially when the performance of sustainable development is linked to their salaries, managers have the incentive to engage in greenwashing (a method for conveying a deceptive impression or providing misleading information about a company’s environmentally sound products) within ESG reports or attempt to distinguish itself from other enterprises by selectively disclosing good news [6,7,8].

ESG assurance is conducive to alleviating concerns raised by stakeholders about companies engaged in impression management [9,10]. Specifically, assurance is defined as an engagement in which a practitioner aims to obtain sufficient appropriate evidence to express a conclusion designed to enhance the degree of confidence of the intended users about the sustainability information (IAASB, 2010) [11]. Therefore, ESG assurance can inform stakeholders that the information reflected in the ESG report is supported by evidence and can be tested for accuracy so that they can rely on the ESG report to make effective decisions. In addition, as a kind of external monitoring mechanism, external assurance should have a detrimental impact on decoupling and narrowing the gap between the superficial report and the actual performance in ESG accordingly [1].

Assurance engagements are becoming increasingly critical for organizations to bolster the trustworthiness and reliability of their sustainability reports. This rise in their significance has spurred the development of a robust framework of standards and guidelines. For instance, the European Commission and the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) have set forth mandates for sustainability assurance, and the International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (IAASB) is actively developing new standards for sustainability reporting, presently known as ISSA 5000. This evolving landscape has ignited scholarly interest, with numerous studies examining the practice of sustainability assurance, its motivators, and its economic implications. Notably, though, the bulk of this research has been centered on market responses or the effects on institutional investors [12,13,14,15], with comparatively less emphasis on the impact on non-professional investors’ decisions. Especially in China, non-professional investors have a substantial influence on the market, contributing to more than 80 percent of total trading volume. As a result, they act as marginal investors who play a pivotal role in determining the market prices of securities. However, these investors are at a significant informational disadvantage relative to institutional investors, which exacerbates the issue of information asymmetry. It is in this context that the role of assurance becomes indispensable, serving as an instrument to diminish this asymmetry and support non-professional investors in making well-informed investment decisions. Therefore, a focused investigation into the influence of ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) assurance on the decision-making processes of non-professional investors in China is crucial.

However, because ESG assurance is entirely voluntary in China and guidelines and procedures have not yet been standardized, there are variations in disclosure methods, scope, and application levels when companies seek assurance on ESG reports. This lack of standardization may hinder the comparability of ESG assurance and diminish its potential benefits [16,17]. In response, we further explore how investors evaluate different aspects of ESG assurance, specifically focusing on the mode of presentation and the assured ESG indicators. For the presentation method, assurance reports are typically appended to the ESG report or provided as distinct documents. Currently, the appending approach is more prevalent. Nonetheless, limited attention theory [18,19] suggests that non-professional investors, constrained by time and cognitive load, may overlook the assurance report when it is embedded within the extensive ESG information. An isolated presentation of assurance could potentially render it more conspicuous, thereby possibly heightening its usage and allure for investment. For the assured ESG indicators, under the ISSA 5000 guidelines, the scope of sustainable assurance could be as broad as the entire ESG report or as narrow as the key ESG indicators. Practitioners often assure a selection of ESG indicators rather than the full spectrum. The question arises as to whether a more comprehensive set of assured ESG indicators might alter investors’ evaluations. These issues are unexplored territories that warrant detailed examination in our study, which seeks to illuminate their effects on the investment decisions of non-professional investors.

We employed 1 × 3 and 2 × 2 between-subject experiments to test the effects of ESG assurance, its presentation method, and the richness of assures ESG indicators on the investment willingness of non-professional investors. In the first experiment, the ESG assurance is manipulated by providing participants (i.e., 123 graduate students enrolled in a Master of Accounting program at a leading finance and economics university in China) with the same set of ESG reports but varying the assurance conditions between participants: either no assurance, providing assurance without separate presentation, or assurance presented separately. Consistent with the prediction, our results show that non-professional investors are more likely to invest in companies with ESG assurance than those without. Furthermore, assurance exerts a stronger positive effect on non-professional investors’ investment willingness when presented separately. In the second experiment, 140 graduate students (enrolled in the same program as participants in the first experiment) completed a task where ESG assurance conditions were held and the assured ESG indicators were varied. Different groups of participants are provided with varying levels of richness in ESG indicators. The experimental results indicate that the likelihood of a non-professional investor investing in a firm increases with the richness of assured ESG indicators. Using the experimental research method, we create a purer and less endogenous environment for exploring the economic effects of ESG assurance. This approach allows us to establish more precise causation compared to other studies conducted using empirical research methods.

The potential contributions of this paper are manifold. Firstly, to the best of our knowledge, this study is pioneering in its exploration of how ESG assurance influences Chinese non-professional investors. In China, non-professional investors, who act as marginal investors, play a pivotal role in determining the market prices of securities. Therefore, exploring the relationship between ESG assurance and the investment willingness of non-professional investors constitutes a fundamental in-depth investigation into the market’s evaluation of ESG assurance. Our findings indicate that ESG assurance has the potential to achieve favorable market assessments, thereby contributing to the literature on the positive economic outcomes of ESG assurance [20,21,22,23,24]. Additionally, unlike the United States and the European Union, where certain regulations require ESG assurance, in China, ESG assurance remains entirely voluntary. Investigating the impact of ESG assurance on the investment decisions of Chinese investors underscores the benefits of voluntarism and provides a valuable addition to the existing literature.

Second, we are the first to investigate how the presentation method of ESG assurance impacts the investment willingness of non-professional investors. The significance of exploring this correlation lies in identifying practical ways to enhance the effectiveness of ESG assurance, thereby encouraging firms to voluntarily seek assurance for their ESG reports. While the industry has shown a preference for including ESG assurance reports as an appendix to the ESG report, our research indicates that disclosing ESG assurance reports separately can actually have a greater impact on investors. Therefore, our findings suggest that companies wishing to emphasize corporate ESG performance may benefit from issuing a standalone ESG assurance report rather than combining it with the ESG report. Additionally, we apply limitation theory and information processing theory to elucidate how the mode of assurance presentation influences investors’ investment willingness, achieving a successful integration of accounting and psychology.

Third, our research enriches the existing literature on ESG assurance scope. Reverte (2020) [15] compared firms that assure their entire sustainability report to those that only assure parts of it, finding that the former tend to have higher market valuations. However, conducting an assurance assessment of the entire ESG report is not always a practical endeavor. ESG reports often contain a significant amount of forward-looking information and qualitative descriptions, which require substantial time and expertise to verify. As a result, practitioners may overlook the most critical ESG indicators, focusing instead on less impactful textual information. ESG indicators are crucial in ESG reports as they provide concrete, quantifiable, and comparable ESG data that enable stakeholders to accurately gauge a company’s true ESG performance rather than relying solely on self-reported information. Therefore, it is crucial to conduct assurance on these indicators to ensure the authenticity of the information and protect investors from making unreasonable investment decisions. In response to this, our study further narrows its focus from ESG assurance coverage to the specific indicators that are assured, delving deeper into the relationship between the breadth of assured ESG indicators and the investment willingness of non-professional investors. Simultaneously, from the perspective of practitioners of ESG assurance, our findings may inspire them to enhance both the quality of ESG assurance and its added value.

2. Literature Review

In recent years, some stock exchanges have introduced mandatory assurance requirements for ESG information. For example, the European Union formally enacted the CRSD (Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive) on 28 November 2022, which expressly requires listed companies to engage auditors or other independent institutions to provide assurance on their sustainability reports. In the United States, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has put forward rule changes that would require registration to include certain climate-related disclosures in their registration statements and periodic reports. Furthermore, they would be subject to undergo third-party verification for the sake of ensuring the accuracy of the disclosed information. However, the vast majority of stock exchanges do not impose mandatory assurance requirements for ESG information; instead, they predominantly encourage such practices. Take the Stock Exchange of Hong Kong, China (HKEX), for example. It released the Environmental, Social, and Governance Reporting Guidelines, which indicated that issuers might consider seeking independent assurance to improve the quality of their sustainability reports. It can be argued, therefore, that for most regions, ESG assurance is not a mandatory institutional arrangement but rather a spontaneous behavior.

While several countries have incorporated measures requiring mandatory ESG assurance, it has not yet reached a global forum. One such step has come from the International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (IAASB), which announced that the public consultation phase for their newly proposed sustainability assurance standard would begin in late July or early August 2023. Once approved, ISSA 5000, with its emphasis on sustainability reporting assurance, will stand as the most comprehensive sustainability assurance standard accessible to assurance practitioners worldwide. Prior to development, the International Standards on Assurance Engagements 3000 and 3410 (ISAE 3000/3410) plus the Account Ability 1000 (AA1000), both used by assurance practitioners to provide sustainability assurance but designed for different objectives, have assumed a predominant position.

Academic research on ESG assurance is still in its initial stage [2]. The first strand of literature is devoted to the descriptive analysis of the disclosure and content of assurance reports, connecting them to the characteristics of the company or assurance practitioners. For example, there exists evidence that firms in Belgium and Sweden exhibit the highest average assurance quality [25]. In terms of assurance providers, previous research shows that accounting firms deliver better quality compared to other third-party organizations as they are professional auditors, and this positive impact can be further strengthened by the growth in the size of accounting firms [26]. However, recent research found that consulting firms provide superior quality assurance by assisting companies in establishing climate-related governance systems [27]. One factor contributing to the inconsistency may be that companies are increasingly prioritizing environmental and climate issues as the era progresses.

The second set of studies concentrates on analyzing the factors that drive companies to voluntarily assure their ESG reports. On the one hand, the country-specific institutional elements can account for variations in assurance practices across different jurisdictions. Aspects such as national stakeholder orientation, legal enforcement, climate risks, and climate governance have been demonstrated to be important drivers of sustainability assurance [25,28,29]. On the other hand, organizations voluntarily conduct assurance on the ESG reports, presumably driven by firm-specific and industry-related factors, including their obligations to external stakeholders [26], improvements in sustainability performance, heightened public credibility, and enhancements in internal systems and processes [26,30]. However, some firms are reluctant to engage auditors or other independent institutions to provide assurance on their sustainable information due to the concern. This hesitation is often attributed to concerns about the additional costs involved and a perceived absence of added value [31].

A third string of literature is dedicated to exploring the economic consequences arising from sustainability assurance. Specifically, a portion of the research pays attention to the impact of sustainability assurance on capital markets. In a study involving a sample of French companies listed in the SBF120 index, Radhouane (2020) [20] demonstrates that higher levels of assured ESG reporting are financially rewarded by investors. Several studies concentrate on examining the impact of ESG assurance on corporate reputation and the quality of environmental information [13,14]. According to Birkley et al. (2016) [13], who analyzed Newsweek magazine’s environmental reputation scores for companies that published CSR reports in 2008 and 2009, there is a positive correlation between sustainability assurance and the environmental image of a firm. Notably, a portion of the research that investigates the perceptions of users regarding sustainability assurance aligns with the subject matter of this paper. For example, by exploring the perceptions of financial analysts regarding disparities in the credibility of sustainability reports, Pflugers et al. (2011) [21] found that analysts tend to rate assured sustainability reports more favorably. Beyond that, sustainability assurance also exerts influence on investor behavior [22], especially for non-professional investors with limited business knowledge. Research indicates that the perceived investment risk of non-professional investors decreases when the listed company’s sustainable information undergoes verification [23]. In addition, the professional competence of the assurance practitioners can further affect investor judgment, leading non-professional investors to often assign superior ratings to high-level assurance providers [24].

3. Hypothesis Development

3.1. The Effect of ESG Assurance on Investment Willingness of Non-Professional Investors

Information serves as the bedrock for non-professional investors when making investment decisions. By merging financial and non-financial data, ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) information offers insights into a company’s sustainability, assisting investors in forecasting future profitability. A substantial body of research indicates that ESG assurance, which confirms the reliability of ESG information through unqualified opinions, is highly informative. This validation boosts investor confidence in the sustainability information provided, enhancing their perception of a company’s ESG performance as a factor in improving social reputation and business performance [23]. As a result, it elevates investor expectations regarding the company’s future profitability.

From the viewpoint of the Information Asymmetry Theory, the assurance process plays a pivotal role in diminishing the informational gaps between firms and investors. This reduction in asymmetry ensures that stakeholders are well-informed about the adequacy of a company’s actions regarding sustainability [8,26,28]. As a result, this transparency enhances non-professional investors’ confidence and, consequently, their propensity to invest in the company. From the lens of the signaling theory, the voluntary assurance of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) reports by third parties acts as a mechanism to signal superior sustainability performance, as discussed by Sauerwald and Su (2019) [1]. This assurance process not only boosts the utilization of ESG information in investment decisions but also enhances investor confidence in the company. Therefore, assured ESG information is typically viewed more favorably by individual investors compared to general, non-assured ESG data.

Based on the above discussion, the first hypothesis is formulated as follows:

Hypothesis 1.

Individual investors are more likely to invest in companies with ESG assurance than those without.

This hypothesis is not without tension, as the utility of ESG assurance has been questioned. For example, Fazzini and Dal Maso (2016) [30] investigated the impact of ESG disclosure and assurance reports on the value of 48 listed Italian companies. They found that about half of these companies seek assurance for their ESG information, but this behavior did not lead to any incremental benefits. Furthermore, it has been argued that ESG assurance reports are not sufficiently transparent or useful and are largely detached from key sustainability issues of interest to stakeholders [32]. In fact, the fundamental reason why assurance makes ESG reports an effective signal is that the professional level of the assurance provider, along with the standards and procedures of the assurance service, ensures the credibility of ESG reports [33]. However, in China, given that ESG assurance is not a mandatory requirement, the institutional framework is not yet fully developed, and there are deficiencies in the assurance providers, standards, and procedures. Therefore, there is a possibility that ESG assurance will not increase Chinese non-professional investors’ willingness to invest.

3.2. The Effect of ESG Assurance Presentation Method on Investment Willingness of Non-Professional Investors

In terms of presentation, ESG assurance reports are typically included as appendices within ESG reports. However, this format may not be optimal due to the ‘limited attention theory’, which posits that investors often struggle to process all available market information promptly because of constraints on their time and energy [18,19]. When ESG assurance reports are merely appendices, investors with limited attention may find it challenging to discern this information quickly and accurately amidst an overload of data. Consequently, the potential investment attractiveness offered by ESG assurance might be diminished.

Further, the Information Processing Theory delves into how attention is allocated and suggests that individuals tend to focus more on information that is readily accessible, which increases its frequency of use [34]. For instance, Peress (2008) [35] observed that quarterly earnings announcements prominently featured in the Wall Street Journal typically trigger stronger market reactions and less subsequent price drift compared to those not highlighted in the media. Therefore, presenting ESG assurance reports separately rather than as part of an ESG report could significantly enhance their visibility to investors. This increased accessibility likely leads to more frequent usage and elevates their value as a consideration for investment.

Based on the above discussion, the second hypothesis is formulated as follows:

Hypothesis 2.

Non-professional investors are more likely to invest in companies that present their ESG assurance separately than in companies that do not.

3.3. The Effect of the Assured ESG Indicators on Investment Willingness of Non-Professional Investors

In ESG assurance, practitioners often select a part of ESG indicators as their subject matter because the entire report contains a significant amount of forward-looking and value-chain information that can make it challenging to draw objective conclusions. This selective assurance process is not merely a practical decision but a strategic one that significantly influences investors’ perceptions. The depth of the assured ESG indicators reflects the diligence of the assurance providers and impacts how investors gauge their competence [36]. When the assurance meets investors’ expectations for professionalism, it positively affects their valuation of the ESG efforts, thus influencing their investment decisions [24].

From the perspective of signaling theory, the inclusion of a rich array of assured ESG indicators acts as a potent market signal. It not only communicates a company’s commitment to transparency but also indicates confidence in the accuracy and veracity of its ESG disclosures. Such signals are crucial for potential investors who are increasingly looking to invest in companies that demonstrate a commitment to ethical practices and long-term sustainability goals, making it a more attractive investment. Moreover, the readiness to provide comprehensive and accurately assured ESG information also reflects a company’s proactive stance in embracing responsibilities that extend beyond the narrow pursuit of profit. This broader commitment to ethical standards and sustainability is increasingly recognized as a fundamental component of a company’s long-term value creation, making it an attractive proposition for investors. Based on the above discussion, the third hypothesis is formulated as follows:

Hypothesis 3.

The likelihood that an individual investor will invest in a firm increases with the richness of the assured ESG indicators.

4. Research Method (Experiment One)

4.1. Experimental Design

The first experiment uses a 1 × 3 between-subject experimental design, which aims to investigate the impact of ESG assurance and its presentation method on the investment willingness of non-professional investors (H1 and H2). The independent variable is assurance (no assurance, assurance without separate presentation, assurance presented separately). The dependent variable is the participants’ investment willingness.

4.2. Research Instrument and Administration

Prior to the start of the experiment, subjects were randomly assigned to one of three experimental groups (the three levels of assurance). Subsequently, each group received its respective experimental materials, with each participant having access to only one of the three groups of experimental materials. The experimental material was developed based on ESG reports and ESG assurance reports issued by a large mining company.

The experimental materials are segmented into four components: the task guide, case information, investment task, and demographic information. Within the task guide, participants are informed that they are the potential investors required to make investment decisions based on the case information. Next, the case information encompasses two sections: one is the background and financial information, which remains consistent across all three groups, and the other is the ESG information, which serves as the independent variable to be manipulated. Specifically, background information contains the industrial environment, primary business operations, firm size, and so on; financial information mainly refers to the key financial indicators over the past three years. It is notable that providing positive financial information aims to instill confidence in the participants regarding the financial performance of cased company.

ESG information varied by the level of independent variable. In particular, the manipulation of assurance (i.e., independent variable) was conducted by providing different ESG assurance reports to the participants in each treatment group [21]. In this study, assurance was manipulated at three levels: no assurance, assurance without separate presentation, and assurance presented separately. In the no-assurance groups, the participants were given an ESG report without assurance. In the assurance without a separate presentation group, the participants received an assured ESG report, but the assurance report is included in the appendix of the ESG report. In the assurance presented separately group, the participants received an ESG report and an assurance report separately.

After reading the above material, the participants were asked to express their investment willingness (Question 1 measures the dependent variable) and their perception of ESG performance (Question 2 measures the mediator variable). In line with previous research [37], this study employed investment likelihood as an indicator of investment willingness. Participants rated their inclination to invest using an 11-point Likert scale (from 0 “highly unlikely to invest” to 10 “highly likely to invest”). Finally, we required participants to provide their demographic information, including gender, work experience, financial and accounting expertise, degree of ESG interest, as well as their investment experience and knowledge. Considering the opportunity cost and experimental fatigue of the participants, the entire duration of the experiment was limited to 30 min.

To mitigate endogeneity concerns and enhance the reliability of the experimental outcomes, this experiment was conducted as follows: (1) To prevent deliberate guidance or intervention with the participants, we randomly chose the experimental facilitator. (2) When inquiring about their investment willingness, participants were not intentionally encouraged to concentrate on ESG information. (3) The experimental materials were designed to maintain roughly equal lengths of background and ESG information, with no emphasis placed on ESG information.

4.3. Participants

The participants are 123 postgraduate students enrolled in a Master of Accounting program at a reputable finance and economics university in China, who acted as surrogates for non-professional investors. All participants consisted of 29% males and 71% females, with an average of 3.9 years of work experience and an average of 10 courses related to accounting and finance. Additionally, 68% of the participants had prior experience in the stock market and expressed an intention to invest in it in the future.

The validity of this approach has been supported by a study that compared the responses from students pursuing a Master’s in Finance and Accounting and non-professional investors, drawing a positive conclusion about the validity of using postgraduate students as surrogates for non-professional investors [18,38,39,40,41] The reasons are as follows: First, their sufficient understanding of finance and accounting allow them to grasp the experimental requirements and successfully fulfill the task [40]. Second, students are one of the purest groups of people, least disturbed by social factors, and thus can reflect the true nature of individuals to a greater extent. This is particularly important for exploring human investment behavior. Third, considering the accessibility of experimental subjects, students are not only readily available but also have a relatively steep learning curve and a relatively low opportunity cost.

Additionally, to reduce the disparity in decision-making between students and professional investors and further enhance the reliability of the experimental results, “intend to invest in the stock market” or “paying attention to the stock market” were used as criteria to screen participants with a background in investing knowledge. Historically, individual investors in China were viewed as poorly educated and irrational. However, as China’s capital market has matured and efforts to educate and protect individual investors have increased, these investors have gradually been characterized as rational and robust. According to the 2020 Individual Investor Status Survey Report released by the Shenzhen Stock Exchange, the percentage of investors embracing long-term value investment concepts has been increasing annually, rising from 20.4% in 2015 to 31.1% in 2020. Simultaneously, the percentage of investors exhibiting irrational investment behaviors, such as excessive fear and overconfidence, has been decreasing year by year.

Therefore, graduate students in finance and accounting with some investment knowledge can serve as a reasonable alternative to non-professional investors in China.

Moreover, all participants were provided monetary incentives associated with final experimental gains in order to improve participation motivation and bolster the reliability of experimental conclusions.

4.4. Results

4.4.1. Randomness Inspections

In general, the individual characteristics of participants, such as gender, age, years of working experience, investment experience, and other factors, may affect the results of interference experiments. To eliminate this potential interference, this experiment used the method of randomized grouping to group the participants and then utilized ANOVA to test the effect of randomized grouping. As shown in Table 1, there is no significant difference in the individual characteristics of the subjects between the groups (P-value is not significant), which means that this experiment has achieved randomized grouping for participants with different individual characteristics, thus improving the reliability and credibility of the experimental conclusions.

Table 1.

One-way ANOVA for participants’ personal characteristics (Experiment One).

4.4.2. Manipulation Checks

To confirm the effective manipulation of the independent variable, this experiment asked the participants to respond to questions related to the manipulation test after they had answered the case-related questions. Concerning the manipulation of whether ESG assurance was conducted, we asked the participants, “In this case, did the company have the ESG assurance report?” Participants were presented with the options “yes” or “no”, and all 123 participants chose the correct option. This indicates that we successfully manipulated the scenario of ESG assurance. Regarding the manipulation of whether ESG assurance reports are disclosed separately or not, we presented the participants with the question, “In your opinion, do you think the ESG assurance report in this case is disclosed separately from the ESG report?” Participants were given the choice between “Yes” or “No”. Only two participants answered incorrectly, indicating that whether or not the ESG assurance report was separately disclosed was also successfully manipulated.

4.4.3. Hypothesis Test

Hypothesis 1 expects that individual investors are more likely to invest in companies with ESG assurance than those without. To test this hypothesis, this paper combines the assurance without a separate presentation group and assurance present separate group to create a single group for assurance, then applies a one-way ANOVA for testing.

The results, as shown in Table 2 Panel A, show that there is a significant difference between the investment likelihood of non-professional investors in the no-assurance group and assurance group (F = 29.212, p = 0.000). In addition, the descriptive statistics in Panel B show that the mean investment likelihood for the assurance group is 8.57, while for the no-assurance group, it is 7.07. The higher mean investment likelihood in the assurance group supports Hypothesis 1.

Table 2.

The effects of ESG assurance and presentation method on investment willingness of non-professional investors.

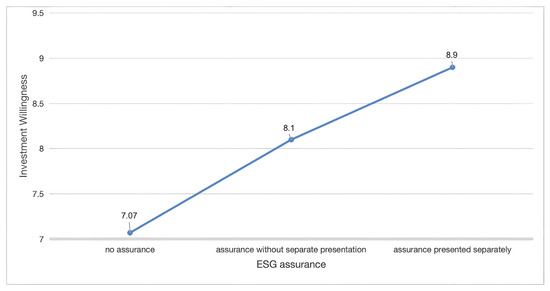

Hypothesis 2 expects that individual investors are more likely to invest in companies that disclose their ESG assurance separately than in companies that do not. This study utilizes the Least Significant Difference (LSD) to test this hypothesis. The results, as shown in Table 2 Panel C, indicate that there is a significant difference between the individual investor attractiveness of the no separate disclosure group and assurance presented separately group (p = 0.009). Furthermore, the descriptive statistics reveal that the mean investment attractiveness for the group with separately presented assurance is 8.90, whereas for the group without separate disclosure of ESG assurance reports, it is 8.10. This higher mean investment attractiveness in the separately presented assurance group also lends support to Hypothesis 2. The experimental results are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The effect of ESG assurance and its presentation method on investment willingness of non-professional investors.

4.4.4. Mediation Analysis

Hypothesis 1 contends that ESG assurance affects non-professional investors’ willingness to invest, which has been verified in the above analysis. Next, the test of the mechanism will be developed in this section. According to the above analysis, assurance increases the confidence in sustainability information for investors and accordingly improves their perception of corporate ESG performance, which in turn enhances their willingness to invest. Therefore, it is reasonable to speculate that the relationship between ESG assurance and the investment willingness of non-professional investors is mediated by the investors’ perception of corporate ESG performance. To test the speculation, this study utilized Baron and Kenny’s (1986) three-step regression method to construct the mediation model.

MEDIATORi = a0 + a1IVi + ei

DVi = b0 + b1IVi + ei

DVi = c0 + c1IVi + c2MEDIATORi + ei

In this model, the independent variable (IV) is the ESG assurance of a company, the mediator variable (MEDIATOR) is the non-professional investors’ perception of corporate ESG performance, and the dependent variable (DV) is the investment willingness of non-professional investors. In this paper, ESG assurance is constructed as a dummy variable that takes 1 when a firm performs ESG appraisal and 0 otherwise. Data for the mediator variable were gathered from Question 2 in Experiment 1, where participants were asked to rate the company’s ESG performance on an 11-point scale.

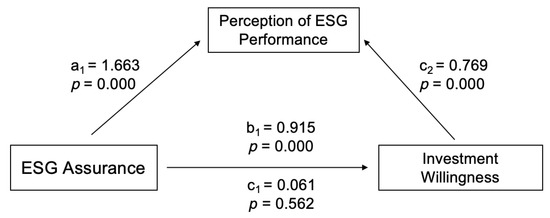

The results of the mediation analysis are shown in Figure 2. The regression results in Equation (1) reveal that ESG assurance significantly influences investors’ perception of corporate ESG performance (a1 = 1.663, p = 0.000). In Equation (2), the results demonstrate that ESG assurance has a significant impact on the investment willingness of individual investors (b1 = 0.915, p = 0.000). Furthermore, the results of Equation (3) show that investors’ assessments of corporate ESG performance significantly affect their investment intentions. Notably, the corporate ESG assurance significantly influences the investment willingness of non-professional investors (c2 = 0.769, p = 0.000; c1 = 0.061, p = 0.562), and the coefficient of ESG assurance in Equation (3) is smaller than that in Equation (2). The results indicate that investors’ perception of corporate ESG performance mediates the impact of ESG assurance on the investment willingness of non-professional investors. This implies that the specific pathway through which ESG assurance affects the investment willingness of non-professional investors is as follows: ESG assurance initially influences investors’ perception of corporate ESG performance, which subsequently affects their judgments regarding investment willingness based on their evaluation of corporate ESG performance.

Figure 2.

Mediating effect on the relationship between ESG assurance and investment willingness.

5. Research Method (Experiment Two)

5.1. Experimental Design

The second experiment uses a 2 × 2 between-subject experimental design, which aims to investigate the effect of the richness of assured ESG indicators on non-professional investors’ investment intentions (H3). In this context, we employed the number (quantity: abundant versus few) and scope (quality: comprehensive versus incomplete) of assured ESG indicators as the measures of richness, serving as the two independent variables in this experiment. Based on the research and analysis of ESG assurance reports, this paper categorizes the quantity of assured ESG indicators as “Abundant“ when it totals 10 or less and “few“ when it exceeds 10. A comprehensive scope of assured ESG indicators encompasses data related to environmental performance (E), social performance (S), and economic performance (G), while an incomplete scope indicates that the indicators do not fully cover data on these three dimensions. The dependent variable is the participants’ willingness to buy shares from a fictitious company.

5.2. Research Instrument and Administration

In line with experiment one, participants were provided with a set of experimental materials related to the cased company. Information directly associated with the two independent variables was subjected to manipulation, while the remaining information (background and financial data) was kept constant. Specifically, the manipulation of the richness of assured ESG indicators (i.e., independent variable) was conducted by providing different assurance reports to the participants in each treatment group [21]. In this study, the richness of assured ESG indicators was manipulated at four levels: abundant assured ESG indicators with a comprehensive scope, few assured ESG indicators with an incomplete scope, abundant assured ESG indicators with incomplete scope, and few assured ESG indicators with a comprehensive scope. The number and scope of assured ESG indicators are determined by the richness in each group. For example, in the abundant assured ESG indicators with a comprehensive scope group, participants received an ESG assurance report whose assured ESG indicators exceed ten and encompass all three categories: environmental performance (E), social performance (S), and economic performance (G).

After reading the above material, the participants were asked to express their investment willingness. Consistent with experiment one, participants rated their inclination to invest using an 11-point Likert scale (from 0, “highly unlikely to invest”, to 10, “highly likely to invest”). In terms of mitigating endogeneity problems and improving the reliability of experimental results, the operation of experiment 2 remains the same as that of experiment 1.

5.3. Participants

The participants are 140 postgraduate students enrolled in a Master of Accounting program at a reputable finance and economics university in China who acted as surrogates for non-professional investors [18,38,39,40,41]. Among all participants, 32% were male, and 68% were female. On average, they had 3.6 years of work experience and had completed approximately 10 courses related to accounting and finance. Furthermore, 71% of the participants had previous exposure to the stock market and expressed an interest in future investment. Referring to experimental incentives and time, the operation of experiment 2 remains the same as that of experiment 1.

5.4. Results

5.4.1. Randomness Inspections

In general, the individual characteristics of participants, such as gender, age, years of working experience, investment experience, and other factors, may affect the results of interference experiments. In order to eliminate this potential interference, the experiment used the method of randomized grouping to group the participants and then employed ANOVA to test the effect of randomized grouping. As shown in Table 3, there is no significant difference in the individual characteristics of the subjects between the groups (P-value is not significant), which means that this experiment has achieved randomized grouping for participants with different individual characteristics, thus improving the reliability and credibility of the experimental conclusions.

Table 3.

One-way ANOVA for participants’ personal characteristics (Experiment Two).

5.4.2. Manipulation Test

To confirm the effective manipulation of the independent variable, this experiment asked the participants to respond to questions related to the manipulation test after they had answered the case-related questions. Concerning the manipulation of whether ESG assurance was conducted, the study asked the participants, “In your opinion, what is the number of assured ESG indicators in this case?” Participants were presented with the options ‘more than 10’ and ‘Less than or equal to 10’, and all 140 participants correctly selected the correct option. This indicates that the experiment effectively manipulated the scenario of ESG assurance. Regarding the manipulation of whether ESG assurance reports are disclosed separately or not, this study presented the participants with the question, “In your opinion, does the scope of the assured ESG indicators in this case cover environmental performance (E), social performance (S) and economic performance (G)?” Participants were given the choice between ‘yes’ and ‘no’. Only three participants answered incorrectly, indicating that whether or not the ESG assurance report was separately disclosed was also successfully manipulated.

5.4.3. Hypothesis Test

Hypothesis 3 expects that the likelihood that a non-professional investor will invest in a firm increases with the richness of the assured ESG indicators. To test this hypothesis, we use ANOVA with multiple comparisons (LSD) method. The results, as shown in Table 4 Panel A, show that there is a significant difference in the impact of both the scope and the number of assured ESG indicators on the likelihood of investment by non-professional investors (p = 0.000). Furthermore, the multiple comparisons (LSD) results in Panel B indicate a significant variation in the likelihood of investment by non-professional investors, which is influenced by the richness of the assured ESG indicators (p = 0.011; p = 0.021; p = 0.008).

Table 4.

The effect of assured ESG indicators richness on investment willingness of non-professional investors.

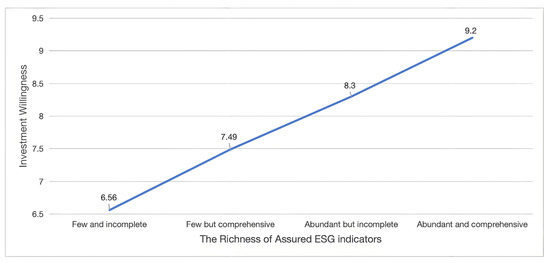

In addition, the descriptive statistics reveal that the mean investment attractiveness for the group with the richest assured ESG indicators is 9.20, whereas for the group with the poorest assured ESG indicators, it is 6.56. This higher mean investment attractiveness in the richest assured ESG indicators group also lends support to Hypothesis 3. The experimental results are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The effect of the assured ESG indicators on investment willingness of non-professional investors.

6. Discussion and Generalizability Caveats

Our results show that non-professional investors are more likely to invest in companies with ESG assurance than those without, and this inclination was heightened by presenting the ESG assurance report separately from the ESG report and by enriching the assured ESG indicators. However, there may be some limitations to the generalization of this conclusion.

First, our findings rely on the premise that investors care about ESG performance, which would not be pronounced in a world where investors do not care about ESG. For example, in the United States, Republicans and Democrats hold starkly contrasting views on ESG practices. Republicans criticize ESG as a manifestation of ‘woke capitalism’, arguing that it wastes shareholder money on hypocritically and politically correct initiatives that benefit executives’ self-image rather than boosting company profits. Under Republican control, Texas even divested $8.5 billion from BlackRock Asset Management Group, a leading proponent of ESG principles. Therefore, our findings may not generalize to these regions. While we focus on non-professional investors, their views on ESG-related investments largely depend on whether sophisticated professional investors consider these factors relevant to value [42]. In a world where investors do not care about ESG, professional investors will struggle to associate ESG factors with value. Such attitudes and behaviors may be transmitted to individual investors through the market, thereby reducing their preference for ESG factors. However, in regions that prioritize ESG performance, such as the European Union and U.S. states like California and New York, which are predominantly governed by Democrats, our conclusion remains clear.

Second, our results may be amplified by higher capital availability. Investor preferences for ESG are determined by capital availability. When capital availability increases in emerging markets, particularly due to massive liquidity injections by global central banks to mitigate the impact of the epidemic, the abundance of capital may allow investors to more freely choose to invest in ESG-compliant projects [43]. Such investments may be viewed as a ‘luxury’, whereby investors with less financial constraints tend to opt for more socially responsible investments and are less concerned with the direct financial return on their investments. However, in an environment of low capital availability, investors may focus more on short-term economic returns and, therefore, be reluctant to pay the additional costs associated with ESG investments. For example, according to the Global Sustainable Investment Coalition, ESG investments in Europe, with relatively high capital availability, represent 48.8% of the region’s assets under management (AUM), whereas in Japan, sustainable investments account for only 18.3% of the region’s AUM. As a result, our conclusions may not be as significant in environments with low capital availability, while they may be amplified in environments with high capital availability.

Indeed, the situations of both limitations on the generalization of conclusions are underpinned by the same logic: whether there are sufficient financial resources to support sustainable development. A significant reason ESG is not universally embraced is the belief that such investments hinder business profitability, with immediate financial returns often prioritized. While the importance of financial considerations is acknowledged, it is crucial to emphasize that focusing solely on short-term profitability without considering sustainability does not ensure long-term success. However, it is also essential to critically assess whether some ESG investments fulfill their promises. Ineffective ESG initiatives can lead to skepticism and the perception that they are merely superficial efforts that detract from profitability. Reflecting on the generalizability of the findings, we also consider whether ESG development in some areas has deviated from its original intent and nature.

7. Conclusions

An increasing number of ESG reports failed to enhance public confidence and information credibility due to a lack of consistency and completeness. ESG assurance can inform stakeholders that the ESG information is supported by evidence and can be tested for accuracy so that they can rely on the ESG report to make effective decisions. Especially for non-professional investors without information advantages, ESG assurance serves as an effective method to alleviate information asymmetry and facilitate informed, rational investment judgments. We employed two experiments to test the effects of ESG assurance, its presentation method, and the richness of assured ESG indicators on the investment willingness of non-professional investors. The empirical findings revealed that individual investors were more inclined to invest in firms that had received ESG assurance than those that had not. Additional analyses showed that these effects were enhanced by both disclosing the ESG assurance report separately from the ESG report and increasing the richness of the assured ESG indicators. Mediation analysis indicated that ESG assurance influenced individual investors’ investment intentions by affecting their perceptions of firms’ ESG performance.

Our study makes a significant contribution to understanding the economic implications of ESG assurance. While prior research often debates the effectiveness of ESG assurance [30,32,33], our study supports evidence that ESG assurance can enhance the investment willingness of non-professional investors [20,21,22,23,24]. Uniquely, our study highlights that separately disclosing ESG assurance reports and increasing the richness of assured ESG metrics can further enhance the utility of ESG assurance. Given that ESG assurance is entirely voluntary in China and guidelines and procedures have not yet been standardized, variations in disclosure methods and scope exist when companies seek assurance on ESG reports. This lack of standardization may hinder the comparability of ESG assurance and diminish its potential benefits [16,17]. We further investigated how investors evaluate the presentation method and the richness of assured ESG indicators of ESG assurance, providing valuable insights for companies aiming to maximize the benefits of ESG assurance and for practitioners seeking to improve the quality of assurance. Additionally, our discussion of the limitations of the generalization of our findings can also shed light on the study of the economic consequences of ESG. Whether ESG works or not depends largely on the local emphasis on ESG and the availability of capital [42,43]. Scholars exploring the economic consequences of ESG should take care to avoid generalizing their conclusions to inappropriate environments.

Nevertheless, our research is not without its limitations. First, we utilize business school students as surrogates for non-professional investors—a common practice in experimental studies. However, it has been critiqued that the investment behavior of students may not fully encapsulate that of actual individual investors, particularly in the context of environmentally focused investments, which could affect the generalizability of our findings. We look forward to the widespread implementation of ESG assurance, which will provide a rich source of relevant data. Once these data are available, large-sample archival studies can be conducted to explore the impact of ESG assurance on stock prices, offering a clearer understanding of how ESG assurance influences the investment decisions of investors. Simultaneously, large-sample archival research has the potential to overcome the limitation of sample size in experimental research. Second, existing research suggests that female investors may have a greater predilection for sustainability information than their male counterparts. Given the relatively high percentage of female participants in our study, this may amplify the perceived investment enthusiasm and the desire for ESG assurance in our results. On the flip side, this opens up a fascinating avenue for further investigation into how demographic variables, such as gender or educational background, influence investor responsiveness to sustainable assurance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.G. and Y.C.; methodology, Y.C.; formal analysis, Y.G.; investigation, Y.G.; resources, Y.C.; writing—original draft, Y.G.; writing—review and editing, Y.G. and Y.C.; supervision, Y.C.; project administration, Y.C.; funding acquisition, Y.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Education’s Humanities and Social Sciences Research Planning Fund project “Risk Identification and Investor Attention Research Based on Financial Technology” (23YJA630014).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to not involving human life sciences and medical research.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Sauerwald, S.; Su, W. CEO Overconfidence and CSR Decoupling. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2019, 27, 283–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummel, K.; Schlick, C.; Fifka, M.S. The Role of Sustainability Performance and Accounting Assurors in Sustainability Assurance Engagements. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 154, 733–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tata, J.; Prasad, S. CSR Communication: An Impression Management Perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 132, 765–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, C.H.; Michelon, G.; Patten, D.M.; Roberts, R.W. CSR Report Assurance in the USA: An Empirical Investigation of Determinants and Effects. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2014, 5, 130–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelon, G.; Pilonato, S.; Ricceri, F. CSR Reporting Practices and the Quality of Disclosure: An Empirical Analysis. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2015, 33, 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, C.H.; Roberts, R.W.; Patten, D.M. The Language of US Corporate Environmental Disclosure. Account. Organ. Soc. 2010, 35, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, T.P.; Maxwell, J.W. Greenwash: Corporate Environmental Disclosure under Threat of Audit. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 2011, 20, 3–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, P.; Fang, X.; Li, Y.; Richardson, G.D. The Relevance of Environmental Disclosures: Are Such Disclosures Incrementally Informative? J. Account. Public Policy 2013, 32, 410–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnea, A.; Rubin, A. Corporate Social Responsibility as a Conflict between Shareholders. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 97, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown-Liburd, H.L.; Cohen, J.P.; Trompeter, G. Effects of Earnings Forecasts and Heightened Professional Skepticism on the Outcomes of Client–Auditor Negotiation. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 116, 311–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (IAASB). Handbook of International Quality Control, Auditing, Other Assurance, and Related Services Pronouncements, Part I; International Federation of Accountants: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rivière-Giordano, G.; Giordano-Spring, S.; Cho, C.H. Does the Level of Assurance Statement on Environmental Disclosure Affect Investor Assessment? Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2018, 9, 336–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkey, R.N.; Michelon, G.; Patten, D.M.; Sankara, J. Does Assurance on CSR Reporting Enhance Environmental Reputation? An Examination in the U.S. Context. Account. Forum 2016, 40, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, R.; Best, P.; Cotter, J. Sustainability Reporting and Assurance: A Historical Analysis on a World-Wide Phenomenon. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 120, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reverte, C. Do Investors Value the Voluntary Assurance of Sustainability Information? Evidence from the Spanish Stock Market. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 29, 793–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürtürk, A.; Hahn, R. An Empirical Assessment of Assurance Statements in Sustainability Reports: Smoke Screens or Enlightening Information? J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 136, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, K.; Subramaniam, N.; Stewart, J. Assurance of Sustainability Reports: Impact on Report Users’ Confidence and Perceptions of Information Credibility. Aust. Account. Rev. 2009, 19, 178–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libby, R.; Bloomfield, R.J.; Nelson, M.W. Experimental Research in Financial Accounting. Account. Organ. Soc. 2002, 27, 775–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirshleifer, D.; Teoh, S.H. Limited Attention, Information Disclosure, and Financial Reporting. J. Account. Econ. 2003, 36, 337–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radhouane, I.; Nekhili, M.; Nagati, H.; Paché, G. Is Voluntary External Assurance Relevant for the Valuation of Environmental Reporting by Firms in Environmentally Sensitive Industries? Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2020, 11, 65–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pflugrath, G.; Roebuck, P.; Simnett, R. Impact of Assurance and Assurer’s Professional Affiliation on Financial Analysts’ Assessment of Credibility of Corporate Social Responsibility Information. Audit. J. Pract. Theory 2011, 30, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaliwal, D.S.; Li, O.Z.; Tsang, A.; Yang, Y. Voluntary Nonfinancial Disclosure and the Cost of Equity Capital: The Initiation of Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting. Account. Rev. 2011, 86, 59–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinsker, R.E.; Wheeler, P.R. Non-Professional Investors’ Perceptions of the Efficiency and Effectiveness of XBRL-Enabled Financial Statement Analysis and of Firms Providing XBRL-Formatted Information. Int. J. Discl. Gov. 2009, 6, 241–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quirós, M.M.M.; Quirós, J.L.M.; Izquierdo, J.D. The Assurance of Sustainability Reports and Their Impact on Stock Market Prices. Cuad. Gestión 2021, 21, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simnett, R.; Vanstraelen, A.; Chua, W.F. Assurance on Sustainability Reports: An International Comparison. Account. Rev. 2009, 84, 937–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dwyer, B.; Owen, D.; Uneman, J. Seeking Legitimacy for New Assurance Forms: The Case of Assurance on Sustainability Reporting. Account. Organ. Soc. 2011, 36, 31–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datt, R.; Prasad, P.; Vitale, C.; Prasad, K. International Evidence of Changing Assurance Practices for Carbon Emissions Disclosures. Meditari Account. Res. 2022, 30, 1594–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, R.; Grenier, J.H. Understanding and Contributing to the Enigma of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Assurance in the United States. Audit. J. Pract. Theory 2014, 34, 97–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolk, A.; Perego, P. Determinants of the Adoption of Sustainability Assurance Statements: An International Investigation. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2008, 19, 182–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazzini, M.; Maso, L.D. The Value Relevance of “Assured” Environmental Disclosure. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2016, 7, 225–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Brorson, T. Experiences of and Views on Third-Party Assurance of Corporate Environmental and Sustainability Reports. J. Clean. Prod. 2005, 13, 1095–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiral, O.; Saizarbitoria, I.H.; Brotherton, M. Assessing and Improving the Quality of Sustainability Reports: The Auditors’ Perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 155, 703–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Wu, H.; Chand, P. The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility Assurance on Investor Decisions: Chinese Evidence. Int. J. Audit. 2017, 21, 271–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinmuntz, D.N.; Schkade, D. Information Displays and Decision Processes. Psychol. Sci. 1993, 4, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peress, J. Media Coverage and Investors’ Attention to Earnings Announcements. Social Science Research Network 2008, 33, 1–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asante-Appiah, B. Does the Severity of a Client’s Negative Environmental, Social and Governance Reputation Affect Audit Effort and Audit Quality? J. Account. Public Policy 2020, 39, 106713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coram, P.; Mock, T.J.; Monroe, G.S. Financial Analysts’ Evaluation of Enhanced Disclosure of Non-Financial Performance Indicators. Br. Account. Rev. 2011, 43, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, W.; Hodge, F.D.; Kennedy, J.; Pronk, M. Are MBA Students a Good Proxy for Non-Professional Investors. Account. Rev. 2007, 82, 139–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, W.; Jackson, K.E.; Peecher, M.E.; White, B.J. The Unintended Effect of Corporate Social Responsibility Performance on Investors’ Estimates of Fundamental Value. Account. Rev. 2013, 89, 275–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Tan, H.; Yeo, F.; Zhang, J. When Do Qualitative Risk Disclosures Backfire? The Effects of a Mismatch in Hedge Disclosure Formats on Investors’ Judgments. Contemp. Account. Res. 2019, 36, 2093–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Tan, H.-T.; Xu, T.; Zhang, J. The Joint Effect of Presentation Format and Disclosure Balance on Investors’ Reactions to Sensitivity Disclosures of Hedging Instruments. Account. Horiz. 2022, 36, 149–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantas, M. Are ESG Funds More Transparent? Soc. Sci. Res. Netw. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Cortes, G.S.; Gao, G.P.; Silva, F.B.; Song, Z. Unconventional Monetary Policy and Disaster Risk: Evidence from the Subprime and COVID–19 Crises. J. Int. Money Financ. 2022, 122, 102543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).