Abstract

This study addresses the challenges faced by the fashion industry and its consumers in relation to sustainability and the circular economy in a digital age, relating them to the impacts that this industry triggers, both environmentally and socially. The aim is to understand the relations between environmental concern, fashion consumer awareness and adaptation to the digital evolution, and how these can result in an intention to buy sustainable fashion. The methodology adopted was based on other studies in the area, allowing us to answer the investigation question and, finally, to present some reflections that could mitigate the problems found. This research concisely highlights the limitations of the current linear economy, demonstrating the difficulties in the transition to a more sustainable world. This article is relevant for researchers in the field of fashion brand communication and consumer behaviour, as the results show some theoretical and experimental content for a better development of strategies and practices in the field of sustainable fashion, taking into account the digital evolution.

1. Introduction

Fashion is known as a cyclical and temporary phenomenon that follows the economy, lifestyles, behaviours and trends of society []. The fashion industry employs more than 300 million people worldwide and represents a significant economic force, operating in an extremely competitive market []. However, this industry cannot remain unconcerned about the impacts of its production processes, as it is one of the most polluting industries in the world, as well as one of the largest, most globalised and dominant industries in the modern world [].

The fashion industry, with its processes of textile production and consumption and the disposability of goods, contradicts the concept of sustainable development, made known in the Brundtland report of 1987, which states that the aim is to satisfy the needs of present generations without compromising the needs of future generations, thus causing significant damage to the environment []. In addition to the environmental issue, there are also social and economic dimensions that involve the fashion system and have an impact on society [].

Thus, along with this reality and taking into account the growing concerns about the sustainable development of the planet, world authorities have been debating ideas to minimize the damage caused to the environment. They are looking for alternatives to reduce consumption and optimize the use of natural resources in order to improve our quality of life [].

On the other hand, the digital evolution, a topic also being studied in the area of fashion consumption, has been changing fashion brands’ processes when it comes to selling their products. The increase in the amount of shared information, knowing the latest news in real time and the exchange of opinions between consumers via mobile apps and social networks has revolutionized the way we act, allowing today’s consumers to have very different characteristics from ten years ago [].

The challenge is to change the way consumers think, rooted in society, in order to achieve sustainable fashion, reinventing consumption and production habits and abandoning fast fashion methods in favour of alternatives such as slow fashion, which proposes a change of vision []. It is important to emphasise that this change will only happen with the awareness of everyone []. Conscious consumption considers collective well-being, the preservation of resources, good working conditions and fair pay [].

The relation between fashion and sustainable development is complex, as it involves reconsidering the practice of consumption []. Thus, a new paradigm is needed to guide society and companies towards satisfying the needs of consumers, who are increasingly aware of environmental issues, but tend to be consumerists in an increasingly digital age.

Each era of humanity is defined by certain characteristics and, in the context of the 21st century, environmental concern is, in fact, the most prevalent. This concern is the result of the rapid development of industry, technology, information and globalisation, which has raised consumption to an unprecedented level. Global Footprint reported that in the first eight months of 2015, all the resources that the Earth is capable of sustainably providing in one year were exhausted []. In 2022, according to the World Wide Fund for Nature [WWF], 28 July was the day when humanity consumed everything that ecosystems can regenerate in one year. Over the last few years, despite the measures implemented in favour of the planet’s sustainability, there has only been an insignificant improvement, showing that there is still a lot to be done in this area.

Therefore, when addressing the central theme of the study, the importance of considering various factors, such as the lack of resources, pollution levels and other environmental challenges, which threaten the continuity of the planet’s inhabitants and certainly that of future generations, is emphasised. This is because economic and social activities depend essentially on goods and services that come from the planet’s resources, including food and clean water, and climate mitigation and cultural links are also important. Some activities have caused major impacts on the planet’s biodiversity and, although these have been diffused from their points of origin, they have continued to accelerate in recent decades, resulting in the environmental degradation of the planet [].

Overall, the years 2020 and 2021 will be remembered in the history books as a time when the pandemic held the world hostage as a result of the outbreak generated by the COVID-19 virus. In its first six months alone, hundreds of thousands of people died, millions were infected, and society was confronted with a lasting economic impact [].

Pandemics, which have appeared over time, are correlated with high population density and high wildlife diversity, driven by human-generated changes, such as deforestation, the expansion of agricultural land, the intensification of animal production and the increase in wildlife harvesting [].

On the other hand, this last pandemic period will also be remembered for the massive use of technological means that triggered a digital revolution, which was already in progress, but which was accelerated by its appearance. This change came about in just a few weeks, although it would have been expected to occur after a decade [].

Facing a reality that is causing serious environmental consequences day by day, it is important to act on all levels in order to reduce the negative impacts. To do this, it is necessary to consider the various dimensions of socio-economic development, looking at a range of issues, from the social to the environmental, which are intrinsically linked to safeguarding the planet’s human and environmental health [].

Coincidentally, in March 2020, the European Commission published a new Circular Economy Action Plan, which covers a strategy for textiles, with the aim of stimulating innovation and boosting reuse in the sector to address the impacts caused []. This represents an important step towards a more sustainable and environmentally friendly fashion industry, including stricter recycling rules and mandatory targets for the use and consumption of materials by 2030. To achieve this, from 2025, EU countries will have to fulfil the requirement for the separate collection of textiles, according to the Waste Framework Directive, approved by the European Parliament in 2018 [].

The relation between fashion and consumption interferes with the goals of sustainability, since the product manufacturing processes themselves exploit workers and non-renewable energies, and consequently increase the environmental impact, causing waste and incalculable damage []. On the other hand, consumers need to buy these same products, which are not eco-friendly, for various reasons, for example, economic reasons, such as price, and social reasons, such as social integration [].

According to Fletcher and Grose (2012) [], the global market operates on the basis of a low-cost economy in order to increase the profits of a few companies, under the aegis of programmed obsolescence, wherein the product is cheap, of low quality and nonhardy. As a result, there is no consideration of the social and environmental impacts of clothing, given that the production chain is far away from the end consumer.

In their economic, social and cultural aspects, human activities have become systemic, but they will only continue if they develop while preserving the environment. In order to be considered sustainable, every human initiative has to be evaluated in four ways: that it is ecologically correct, economically viable, socially just and capable of promoting local cultural wealth [].

The initiative for change must first be undertaken by the industry itself, through fashion designers, since they are responsible for managing the development and production processes. These are the first agents who must think in a cyclical and regenerative way, and they can be the driving force behind unprecedented advances, questioning the whole system in a clear and objective way, and showing their knowledge in debates about future improvements. In this regard, fashion designers and fashion companies must combine product development with the preservation of nature, as argued by [].

According to Braungart and McDonough (2014) [], the need for sustainability in fashion has forced the industry to change. However, an influential change was already expected. However, conventional environmental approaches focus on what not to do, when in fact a break with the current paradigm of the mode of production is required.

Consumers are, therefore, limited in the alternatives available to improve their consumption habits. It is in this context that this research seeks to understand how fashion consumers may or may not be able to be more attentive when purchasing the products or services they are offered, and how brands can reinvent themselves in the face of a new vision of fashion consumption.

In the context of fashion, this research aims to understand the complex relationships between the impacts of fashion production methods, sustainability, the circular economy and the digital evolution, analysing consumer behaviour, knowledge, motivations and the shopping experience. The aim of this research is to provide theoretical and experimental contributions to improve the consumer strategies and practices of companies in the sector.

1.1. Objectives

After describing the general objective of the study, we set out the specific objectives that define the framework of the entire investigation, outlining how far the study will go. For this purpose, and given that the study is related to conscious consumption, sustainable fashion and fashion consumers in the digital age, it is intended that the methodology adopted will make it possible to do the following:

- Relate the concepts of sustainability and the circular economy to fashion consumer behaviour in terms of brand communication and the use of the digital world.

- Explore the relationship between adaptation to the digital evolution (ADE) and sustainable behaviour intentions in the fashion industry. This objective aims to understand how familiarity and engagement with digital technologies and social platforms influence consumers’ propensity to adopt more sustainable consumption practices.

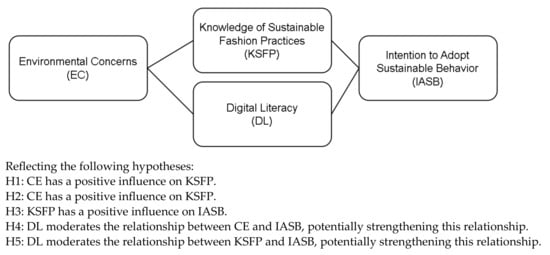

- Examine the moderating role of the knowledge of sustainable fashion practices (KSFP) and technological literacy (ADE) in the relationship between environmental concern (EC) and sustainable behaviour intentions. The focus here is on investigating whether consumers’ specific knowledge of sustainable fashion practices and digital literacy enhance the influence of their environmental concerns on their choice of more sustainable purchasing behaviour.

- Assess the impact of digital influences on sustainable consumer behaviour. This objective focuses the analysis on how recommendations from digital influencers, social media content and digital marketing campaigns can influence consumers’ intention to engage in sustainable fashion consumption practices.

1.2. Relevance of the Study

The study of consumer behaviour in relation to sustainability in fashion is crucial, highlighting the importance of future perception, given the growing shortage of resources and the need for conscious consumption. Over the years, consumers have become more economically, socially and environmentally aware, pushing professionals and companies to offer increasingly sustainable alternatives.

In the fashion sector, sustainable production is a goal, but attracting consumers to eco-friendly products is the key to driving business and government efforts. In this sense, it is equally important for consumers to know the reality behind the tempting low prices, as most of the time these represent a high cost of human exploitation [].

The processes of transforming products or services in a more sustainable way can be realised through recycling, ecological fabrics or reuse. But these sustainable transformation processes will depend on the will of the consumer, which is the reason why it is important to analyse their motivations and behaviours and develop awareness of their attitudes as consumers.

Since this study is related to the areas of management, technologies, the consumer and consumption, it is vital to determine a consumer profile and understand whether it fits in with certain strategies that companies can put into practice, in this case specifically in the field of sustainable fashion.

This study also analyses the consumer profile in relation to business strategies in sustainable fashion, filling a gap in studies in Portugal in that it exceptionally integrates sustainable fashion, consumer and brand behaviour with the current digital evolution in consumption.

In short, this study is relevant because consumers are increasingly demanding of brands and have expectations that influence their purchasing intentions, creating economic, environmental and social challenges for those who produce them. It is, therefore, important to analyse this area, wherein companies need to consider new strategies and consumers need to create new patterns of behaviour and consumption through work, technology and brands and with the planet.

2. Theoretical Background

The fashion industry’s textile production and consumption practices often contradict the principles of sustainable development outlined in the 1987 Brundtland Report []. This contradiction stems from the industry’s significant environmental impacts, as well as its social and economic dimensions []. Despite growing concerns about sustainability, the industry continues to face challenges in reducing consumption and optimising resource use [].

The digital evolution has revolutionised the processes of fashion brands, influencing consumer behaviour through increased information sharing and real-time engagement []. However, achieving sustainable fashion requires a shift in consumer mindset from fast fashion to alternatives such as slow fashion []. Conscious consumption that prioritises collective well-being and resource conservation is essential [].

Environmental concerns have increased in the 21st century due to rapid industrialisation and globalisation, leading to resource depletion and environmental degradation []. The COVID-19 pandemic further highlighted the interconnectedness of environmental and public health crises, leading to accelerated digital transformation [,].

Addressing environmental challenges requires a multifaceted approach that takes into account socio-economic development and environmental protection []. Initiatives such as the European Commission’s Circular Economy Action Plan aim to promote sustainability in the fashion industry through innovation and re-use strategies []. However, the industry’s reliance on exploitative production processes and consumer purchasing habits pose significant barriers [,].

Fletcher and Grose [] argue that the global marketplace prioritises profit over social and environmental impact, perpetuating programmed obsolescence. Sustainable change must begin with fashion designers and companies adopting circular and regenerative practices []. Braungart and McDonough [] emphasise the need for a paradigm shift in production methods to achieve sustainability.

In summary, understanding consumer behaviour in the context of sustainability, the circular economy and digital development is crucial to driving change in the fashion industry. This research aims to explore these complex relationships and provide insights to improve consumer policies and practices, taking into account the digital evolution, and how brands can reinvent themselves in the face of a new vision of fashion consumption.

2.1. Sustainability and the Circular Economy in the Fashion Industry

- Sustainability and Sustainable Development

This Section 2 begins with the theoretical framework, in which concepts of sustainability, sustainable development and the circular economy are first demonstrated. Then, the fashion industry system is characterised to better understand the context of this research. Some of the negative environmental and social impacts of this industry are also explained, demonstrating the importance of a paradigm shift, and the perceptions of fast fashion as opposed to slow fashion and sustainable fashion.

Sustainability in fashion is a topic that has been gaining prominence in recent years. This concept has gained visibility due to climate change, environmental degradation and consequent environmental concerns, becoming a global concern [].

The study of this concept has been highlighted by various issues, already mentioned above, but on the part of consumers, questions arise related to the economic and environmental crises in force around the world, such as the origins and working conditions involved in the production of goods.

In view of the concerns expressed by consumers, many companies have begun to publicise behaviours related to preserving the environment, using the concept of sustainability to add value to their product [].

The purely strategic use of the concept of sustainability is often recurrent, and it is, therefore, essential to know its origin and understand it to clarify the authenticity of its use. According to the Portuguese language dictionary, the word “sustentável” derives from Latin and means “to sustain”, referring to that which has the necessary conditions to be conserved, and can, therefore, be achieved through sustainable development.

It is important to emphasise that the term sustainability first appeared, without the concept being known at the time, in the book The Limits to Growth, written by Donella H. Meadows, Dennis L. Meadows, Jørgen Randers and William W. Behrens III in 1972 []. In some excerpts from the mentioned book, concepts associated with sustainability appear, including the balanced way in which natural resources are utilised to satisfy one’s own current well-being, while preserving future generations’ right to use the same resources. It was, therefore, made clear that it is important for natural resources to still be available in the long term []. Although environmental problems have existed for a long time, it is only recently that economic analysis has come to fully recognise them and consider all their implications [].

The concept of sustainable development emerged a few years later, in 1987, by experts from the UN, from the “Our Common Future” Report, published by the World Commission on Environment and Development, which states the following: “Sustainable Development consists of making humanity capable of satisfying current needs without compromising the needs of future generations” [].

According to the report, the term sustainability does not refer to a state of harmony, but rather to a process of change, wherein the exploitation of resources, the direction of investments, the orientation of technological development and institutional changes are made in accordance with the needs of the present and the future.

Since that time, the definition of sustainable development has appeared in numerous citations in the literature. However, it was later interpreted in an excessively broad sense. As a result, the term sustainability was often used to justify any activity, as long as it reserved resources for future generations. But in a more rigorous sense, it means that the activities carried out must be subjected to additional evaluation to determine all their effects on the environment [].

The concept of sustainability is complex, as it includes a set of interdependent variables—economic, social and environmental []. The great creator of this proposal was John Elkington, when he published the article “The Triple Bottom Line: What is It and How Does It Work?”, back in the 1990s, giving rise to the new concept known worldwide as the Triple Bottom Line [,]. This pioneer defended the idea of measuring company results based on three basic pillars, which became known as the 3 P’s (people, planet and profit).

Thus, the three pillars refer to concepts such as viability (economic level), fairness (social level) and correctness (environmental level), and these relate to each other, with the term sustainability emerging as a product of this convergence []. The development we seek to achieve on a global scale must be socially just, because the objectives of development are always ethical and social; economically viable, because economic viability is a necessary condition for the development of any project that claims to be sustainable. And it must be environmentally sound, because development must take place in a way that respects ecological constraints, thinking in the long term and taking future generations into account [].

Companies that seek a healthy relation with natural and social resources and, at the same time, think about profit, are companies that are integrated into the concept of sustainability, in order to obtain positive results on these three bases [,].

Responsibility in management must go beyond profit, as consumers expect much more than just a good product or quality service on the market. Companies’ involvement and interest in marketing practices and in their stance on sustainability has been increasing. However, it is notable that many companies consider profitability to be their main performance indicator, as highlighted by Kolstad (2007) []. As such, managers have the task of balancing the trade-offs between profitability and sustainable value creation, yet managers choose profitability over sustainability whenever they are in conflict []. As such, short-term thinking in companies still has a major influence [] and is in apparent conflict with sustainability, whose benefits accrue over the long term [].

To put the essence of sustainability into practice, the United Nations (UN) launched the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development in September 2015 as an outline shared by 193 countries to address sustainable development. This agenda introduces 17 sustainable development goals (SDGs) and calls on all governments and private companies to support the realisation of the specified SDGs [].

To meet this agenda, there are a number of fundamental concepts, one of which is discussed in the next section, the circular economy.

- Circular Economy

The circular economy has gained prominence in various sectors and markets around the world []. The topic has been disseminated, and the number of publications has increased considerably []; the principle of this model is to rethink the way we produce and use natural resources [].

In 1982, the article “The product-life factor” was the first publication to refer to the significance of the closed economic loop []. According to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation [], the origins of the concept of the circular economy have diverse histories and philosophies, and are being widely studied today, as it is an option that seeks to redefine the notion of development, with a focus on benefits for society in general. The idea of giving back to the environment what is taken from it reappeared in industrialised countries after the Second World War, when studies based on non-linear systems clearly revealed the complex, correlated and unpredictable nature of the biodiversity that is planet Earth.

The Ellen MacArthur Foundation concluded that this circular economy model summarises the thinking of various philosophers, such as Walter Stahel’s functional service economy, William McDonough and Michael Braungart’s Cradle to Cradle design philosophy, and the biomimicry articulated by Janine Benyus, among others [].

According to Braungart and McDonough (2014) [], if human beings really want to prosper, they will have to learn the concepts of the circular economy, using products as nutrients, which by imitating the natural metabolism simultaneously eliminates waste. The circular economy generates an economic model that seeks to increase the importance of natural resources by keeping them in use for as long as possible, i.e., extending the life cycle of a product in order to avoid excess waste.

For Ghisellini, Cialani and Ulgiati (2016) [], this involves adopting the 3Rs policy—reduce, reuse and recycle:

- -

- Reduce, through better technologies, more compact products, simpler packaging, more efficient appliances and simplifying lifestyles.

- -

- Reuse, by requiring fewer resources (energy, labour, etc.) instead of buying a new product.

- -

- Recycle, so that waste is transformed back into resources.

The circular economy is one of the pillars in the fight against climate change and the fight for a more sustainable development of the planet, in line with the goals set by the UN. A circular economy is understood as an economy that actively promotes the efficient use and productivity of the resources it boosts, through products, processes and business models based on the dematerialisation, reuse, recycling and recovery of materials [].

According to the Circular Economy Action Plan, progress in circularity is achieved when we move from strategies that promote useful applications of materials to strategies for intelligent production and utilisation. Thus, the more “circular” the endeavour, the less need there will be to extract raw materials and, consequently, the less environmental pressure there will be. However, a greater degree of innovation is required in product design and associated standards, at a social and institutional level.

- Linear Model vs. Circular Model

The current linear economic model is notorious for its expression: “extract, produce, use and waste”. This model is reaching its physical limits, as we are witnessing the exhaustion of resources and the devastation of the environment due to the rapid extraction of natural resources. Raw materials and products are sold and, after use, they are discarded as waste, without considering the planet’s regenerative capacity. By 2050, the current model will consume the equivalent of three planets [].

The circular economic model arises from the realisation that the speed of production and exploitation of natural resources is greater than the Earth’s regenerative capacity. Disposal is carried out in a thoughtful way, making more rational and efficient use of resources, redirecting the focus towards reusing, repairing, renewing and recycling existing materials and products. What was previously seen as waste can be transformed into a resource []. Care is also taken to consider the biological cycle (organic) and the technical cycle (non-organic). The biological cycle refers to materials that can safely return to the natural world, even if they have gone through one or more cycles of use, such as food, which returns to the system through composting processes [].

According to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2017) [], the circular model, based on a change wherein renewable energy sources build natural, social and economic capital, is based on three principles:

- -

- Eliminating waste and pollution from the start of production (design products, services and business models that prevent the production of waste and pollution of the natural system);

- -

- Keeping products and materials in use (at their highest economic value and usefulness, for as long as possible);

- -

- Regenerating natural systems (promoting the regeneration of used material and implicit natural resources).

In recent years, there has been an increase in interest from companies and consumers in sustainability and the circular economy. This interest has led to the creation of various ventures in the field of ecology, environmentalism and sustainability. Despite this, in agreement with Augusto (2020) [], in order to bring about a change in mentalities in companies and consumers, it is necessary to face a challenge, as the transition to the circular economy requires significant changes in production and consumption models, despite the existence of the New Circular Economy Action Plan.

- The Fashion Industry and its Impacts

Due to its size and the complexity of its value chain, fashion is one of the industries with the most negative impacts, which makes it unsustainable []. The linear business model present in the fashion industry is limited and triggers a set of negative social, political and environmental consequences []. This industry is the second most polluting in the world, after the oil industry, and the second most water-intensive industry, after the food industry. Within the fashion industry, the sector most responsible for causing the greatest impact on the environment is the textiles and clothing industry, due to the gradual increase in production and consumption [].

According to a 2017 report by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation [], and the United Nations Environment Programme [], the fashion industry is responsible for 10% of all CO2 emissions. If nothing changes in the fashion industry, this share of emissions could reach 26% by 2050. It is estimated that the industry’s environmental impact will worsen by 2030 and triple by 2050, due to the growing demand from emerging markets [,,].

In the problematic context of sustainability and the circular economy, there are already several companies in the fashion industry with environmental concerns related to the use of energy, water, chemicals, CO2 emissions and the production of solid waste. In Portugal, the Portuguese Environment Agency indicates that the Portuguese throw 200,000 tonnes of clothes away every year []. The European Commission Report (2022) [] states that around 5.8 million tonnes of textiles are discarded every year in the EU. This suggests that this is the equivalent of approximately 11 kg per person. However, it is also important to know that every second, somewhere in the world, a lorry full of textiles is landfilled or burned. Clothes made from non-biodegradable fabrics can remain in these landfills for up to 200 years. Only 20% of clothes are collected for reuse or recycling. Less than 1% of all materials used in the manufacture of clothing are recycled to make new garments [].

A garment goes through several phases, all of which make up the product cycle, and which jeopardise the continuity of the planet. In the production phase, large quantities of water and energy are used, greenhouse gases are emitted and large volumes of waste are created, polluting water and the atmosphere []. The post-production phase (dyeing, printing and finishing) is no different, as it has a major negative effect on textile production, since hazardous chemicals are used intensively []. Finally, the consumption phase also has a major impact, as most garments are washed very frequently []. It should be noted that in the use and end-of-life phases, there are still negative effects caused by the disposal of garments in landfill sites [].

To cope with environmental degradation and the decarbonisation of industry, companies will have to adapt their supply chains. According to McKinsey (2019) [], 71% of the emissions savings that the fashion industry can make are within the production cycle. This industry has the longest and most complex in-industry chain, especially when it comes to the production phase. On a social level, the negative impact is related to the environmental issues already described, which affect public health, but also to the undignified labour issues that exist in factories [,]. Furthermore, the negative impact of this industry should also be a financial concern for brands [].

The global market for the clothing and textile industry has Bangladesh, China, India, Turkey, Pakistan and Vietnam as its main suppliers. Some of these countries are extremely dependent on this industry. One example is Bangladesh, in which it accounts for around 80% of total export earnings and generates more than 4 million direct jobs [].

In 2013, in the capital of Bangladesh, in the Rana Plaza building, more than a thousand people lost their lives, in one of the biggest tragedies in industrial history, which prompted the creation of the “Fashion Revolution” movement. Several labels of global fashion brands were involved in this tragedy, making it clear that the fashion industry needed to rethink its production processes [].

This movement led to the worldwide discussion of various issues, exemplified by #WhoMadeMyClothes, #WhoMadeMyFabric, and #WhatsInMyClothes, driving the transparency of brands over their production chain. The movement later grew into an institution with the mission of developing a global fashion industry that conserves and restores the environment, while valuing people above growth and profit. In this sense, what was known as “Fashion Revolution Day” became a week of events, actions and activities [].

Over time, actions have emerged that have helped to make the fashion world more sustainable. For example, in 2007, the non-governmental organisation Greenpeace succeeded in getting the European Parliament to impose restrictions on the import of cotton grown with pesticides that endanger public health and/or with labour without decent working conditions. In 2014, this organisation also took several actions against some fashion brands, helping to promote what is still necessary today: production free of toxic materials.

- Consequences of the Unsustainability of the Fashion Industry

The fashion industry has contributed to unsustainable patterns of overproduction and overconsumption, as the period of use is becoming shorter and shorter before garments are discarded [].

The fast fashion system, or disposable fashion, is a very common industrial system that encourages consumers to buy clothes continuously. This system has a short production and distribution time, offering new products to the market of a lower quality at a lower price. This system, thus, has an impact on both environmental and social sustainability, producing a high level of waste and disposal [].

However, the high amount of discarded clothing has led to the existence of means or channels in the market where end-of-life garments can be sent, such as donation campaigns, clothing recycling bins, among others [,].

The fate of the clothes that consumers buy and wear depends on the consumption habits, norms and practices of each country, as well as the culture and availability of alternative resale channels and recycling systems [].

According to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2017) [], more than half of all clothes in the world are sold in Europe, North America and China, but 10% of these clothes end up in other countries after use. It is, therefore, necessary to create a clothing collection system for these destination countries, most of which do not currently have formal collection systems. This is fundamental to reducing the impact of the fashion industry and consumerism worldwide. In this sense, according to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2017) [], in order to improve end-of-life methods for garments (existing garments), it will be necessary to do the following:

- -

- Increase the acceptance of collection systems in countries where there is already collection of used clothing, expanding the scale of these initiatives;

- -

- Implement actions to create collection systems in countries that do not have schemes in place.

The collection, sorting and recycling processes need to be implemented and/or improved, not forgetting their economic attractiveness. It is necessary to create additional processes to collect clothing after use, especially where there is no method in place [], for example such that leftovers from textile factories can be used for recycling.

These measures require actions to improve the economic incentives for those who re-collect, while at the same time making it more convenient for those who consume, to keep the materials in the system. However, for this to happen, there needs to be a greater understanding of the advantages and disadvantages of existing schemes, facilitating their expansion. For Fashion Revolution Portugal (2016) [] the so-called “clothes recycling bins” may seem like a great idea at first, but they hide a very complex and harmful reality for underdeveloped countries. Recycling and reusing are crucial nowadays, but when it comes to clothes, so much is consumed, and, therefore, donated, that it is impossible to dispose of it through humanitarian actions alone.

There is still a long way to go to make this a reality, but the World Wide Fund for Nature, one of the world’s leading environmental NGOs, believes that it is possible if the industry and stakeholders take the necessary steps to transform.

Fashion, therefore, needs to steer a course towards a more sustainable future, given that fashion cycles and trends contribute to high levels of consumption, caused by consumer dissatisfaction, which generates irreversible environmental and social damage in the long term [].

2.2. Brands and Consumers in the Dynamics of Fashion in a Digital World

At this point, still within the theoretical context, the behaviour of fashion brands is explored in the face of the challenges of sustainability and increasing digitalisation, trying to understand how to break the linear circuit that the economy has entrenched. Next, a link is found between the topics previously covered and the evolution of the digital landscape, highlighting the influence of social networks and the impact of the pandemic on digital transformation. This aims to understand the new modes of consumption more broadly, and then specify the context of consumption in the fashion industry. Finally, we look at the factors influencing the intention to buy sustainable fashion, wherein we characterise fashion consumers, studying their knowledge, habits, behaviours and motivations, referring to psychology in the world of fashion, understanding the characteristics of sustainable consumer behaviour and how this environmentally and socially conscious consumer influences the sustainable fashion purchasing decision process.

- Fashion Brands

Brands are extremely valuable assets, capable of influencing consumer behaviour, being bought and sold and offering their owners the security of constant future income []. According to Rech and Ceccato (2010) [], fashion brands have the function of creating products based on the needs and desires of consumers, which indicates that the relation between individuals and the brand is relevant. Therefore, making a brief comparison between the behaviour of fashion brands and their relationships with the sustainability of the planet becomes essential to this research, given that fashion is exposed and assimilated, according to (Lipovetsky, 2007) [], not as a product, but as a value and translation of personalities.

Firstly, it is important to address brand identity; Kotler and Keller (2012) [] defend it as a set of associations that represent what the brand does and what it guarantees consumers. Lipovetsky and Roux (2005) [] point out that building a brand identity is complex and involves a lot of dedication. They also add that it is crucial for good communication, as a brand only exists if it is communicated. In this sense, in order to stand out from the competition, companies in the fashion sector are always looking for innovation and value creation to add to their products. Brands have been forced to keep up with certain trends so as not to lose their reputation []. One example that is closely linked to the subject of this study is the misuse of concepts related to sustainability in brand communication. These actions are known as “Greenwashing” and are intended to promote a misunderstanding of the policies or products that companies have, claiming that they are more sustainable than they actually are.

According to Rauturier (2021) [], in the fashion world, transparency can be defined as the practice of openly sharing information about how, where and by whom a product was designed. Being transparent means publicising all the information about everyone involved in the production process, from start to finish, i.e., from obtaining the raw materials (agriculture) to the shop shelves (final product). This allows customers to know exactly what they are buying, with details of every stage of the production process. According to Somers (2021) [], transparency is when companies know and publicly share the expression #WhoMadeMyClothes, from who grew the cotton, to who dyed the fabric, to who sewed it, showing under what conditions this took place and highlighting their environmental impacts.

As expressed by Carry Somers, co-founder of Fashion Revolution, in 2016, only 5 of the 40 big brands (12.5%) disclosed their suppliers. However, by 2022, 121 of the 250 big brands (48%) disclosed their suppliers. Currently, brands disclose more information about their return methods than where the clothes actually end up, which ends up hiding who is responsible for wasting clothes [].

However, according to the Fashion Transparency Index report [], fewer brands disclose what really happens to the clothes they receive, with only 26% of brands disclosing this information in 2022, compared to 22% the previous year. The clothes chosen are often sent to second-hand markets, and it is often not possible to give the garments circularity, given their quality, which prevents them from being worn for long periods of time. This clearly demonstrates how the existence of the transparency index and the media around the world questioning #WhoMadeMyClothes has had relevance for brands, motivating them to expose their methods and allowing consumers to make the best purchasing decisions for themselves, the planet and its inhabitants [].

For example, in 2022, H&M was one of the most transparent brands, with a score of 66% out of a scale of 61–70%, making the information mentioned above public. However, this does not mean that it is a more sustainable brand.

In 2022, of the 250 brands analysed, the 21 brands that scored best are listed here:

- -

- OVS, Kmart Australia and Target Australia (78%);

- -

- H&M, The North Face and Timberland (66%) and Vans (65%);

- -

- United Colors of Benetton (63%) and Gildan (62%);

- -

- C&A and Gucci (59%);

- -

- Puma (58%) and Dressmann and Esprit (57%);

- -

- Calvin Klein, Tommy Hilfiger, UGG and Zeeman (56%);

- -

- Calzedonia, Intimissimi and Tezenis (Calzedonia Group) (54%).

And among those with the lowest scores, we have Dolce & Gabbana and SHEIN with 2%, and Tom Ford, New Yorker and Max Mara, with 0%. In the luxury segment, Gucci is in first place, and it should be noted that Ermenegildo Zegna was the first luxury brand to publish a detailed list of its suppliers.

According to Kashyap (2022) [], issues in the fashion industry never fall on a single person, brand or supplier, which is why there are more and more investigations and reports on the industry, in order to promote systemic and structural changes, shaping regulations and holding brands to their promises.

Summing up, transparency among brands also promotes the improvement of brands in terms of future comparisons and evaluations. The fashion industry can lift millions of people out of poverty and provide them with decent and dignified livelihoods, but for this to be possible, politics, culture and the industry must change.

Still, on the subject of brands and their behaviour in relation to the sustainability of the planet, in 2024, according to Reuters, Inditex investors will demand to know the list of suppliers, but the Inditex group is almost an exception in the retail sector in that it still keeps the way it manufactures its clothes secret. The justification given is that full disclosure of the supply chain could increase competition for the same suppliers, but, nevertheless, investors are demanding more transparency.

A table comparing the various brands in terms of environmental and social responsibility, developed in the course of this research, is attached.

Of the models present in the sustainable fashion market (zero waste, the circular economy, upcycling, recycling, eco fashion, the sharing economy, ethical fashion and slow fashion), there may still be doubts as to which fashion brands are sustainable or which use the concept merely as a marketing tool. These doubts stem from the communication strategies that these brands use, leaving questions hanging that lead to a lack of trust. Many fashion brands are considered sustainable, as their value chain is based on respect for the three areas of social, environmental and economic impact.

In Portugal, there are a few sustainable fashion brands, but more prevalent are second-hand shops, known as “vintage shops”, which are sustainable shops because their main mission is to reduce waste in the fashion sector. To help understand the market, a survey was carried out of the main and most accessible fashion brands on the market, one at a national level and the other at an international level:

- -

- Portuguese sustainable fashion brands: Isto; Sienna; Ethical Legend; A Outra Face da Lua; ALMA Capsule Collections; BUZINA; CUSCUZ; Jacarandá; NaturaPura; Captain Tom; Näz; INSANE IN THE RAIN; PACTO.

- -

- Other sustainable fashion brands: Boody; CHNGE; Honest Basics; DillySocks; Knickey; Mighty Good Basics; Parade; Yes Friends; tentree; Thought; Kotn; Happy Earth; Little Emperor; Sense Organics; eclipse; Plant Faced; Etiko; noctu; ABLE; Rapnui; Glass Onion; PANGAIA; GANNI; Patagonia.

Therefore, it is important to ensure that the brand identity is aligned with the brand image, because only then will the message conveyed by the company be aligned with the consumer’s perception; otherwise, when it is not in sync, the message conveyed by the company differs greatly from that perception, and consequently, the objectives will be more difficult to achieve. Thus, creating a good brand image helps to build consumer confidence in the brand’s motives, resulting in future benefits in terms of consumer loyalty and the relation with the brand [].

Taking into account brand communication and consumer behaviour and perception, it will be important to address the issue of the digital evolution and digital literacy on the part of consumers.

2.3. Digital Evolution and Consumption

- Digital Evolution

Since the 1970s, the digital evolution has changed the structuring paradigm from the real economy to the virtual economy []. According to Mandiberg (2012) [], the development of technology meant that the Web began to appear in everyday life, reinforcing that everything is connected to each other in a network, and not just by online or offline status.

According to Carvalhal (2022) [], because of the Internet, many people and issues have gained notoriety, as it is possible to disseminate knowledge and information, giving many people the opportunity to express themselves and connect with each other by sharing information, paving the way for social media (also known as virtual or online social networks), simplifying participation and broadening consumer opinion.

As Constantinides and Fountain (2008) [] argue, users do not just consume content, they also produce content, which is the main driver behind the change from Web 1.0 to Web 2.0, resulting in two natural interconnected consequences.

According to Feliciano (2019) [], these are the predominance of impact, and naturally, the need for organisations to introduce themselves into the online environment in order to reach their target audience more widely. In this way, according to Constantinides and Fountain (2008) [], the Internet is not just a means of communication, but a tool that allows social interaction and the sharing of common interests, contrasting with other means of communication by allowing the evolutionary improvement of the community; Web 2.0 is a set of applications, which, according to Shelly and Frydenberg (2010) [], allow consumers to control, generate, distribute, share and create content interactively.

Web 2.0 has completely changed the way consumers and brands relate to each other []. Due to economic, social and, above all, technological advances, the concept of social media has spread []. Social media has facilitated contact between organisations, customers and potential customers, proving to be an essential digital marketing tool for any brand or company []. At the same time, Kaplan and Haenlein (2010) [] describe social media as Internet-based applications that help consumers share opinions, insights, experiences and perspectives. Of the platforms created as part of Web 2.0, the most common are Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, LinkedIn, YouTube and, recently, TikTok.

The evolution of technologies and the Internet has had a major influence on all commercial activities, changing the way we sell and buy and communicate within companies and with consumers. This evolution has also reduced costs, implied an adjustment in relations between buyers and sellers and, overall, has led to competitive advantages in terms of growth, efficiency, effectiveness and innovation []. Despite the competitiveness and demand, platforms, websites and apps not only allow for cost-effective advertising, but also the possibility of creating real relations and making an instant impact on consumers. Consumers are now more receptive to product-related communication from so-called influencers []. In this way, today’s markets need to adapt to the change in the way information is disseminated to the public [].

With all the visible digital evolution, and because of the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a digital transformation, which was accelerated by the start of the pandemic in 2020, bringing with it a new set of challenges that have been met, from the technological to the human []. In this sense and out of necessity, consumers have had to adopt new technologies, based on the need to keep in touch with family members, shop online, telework and take part in virtual events []. The most accessible example was Zoom’s videoconferencing services, wherein many families who had access to the Internet learnt to take part in these virtual meetings through this means.

Also in this context, for Husnaiyan, Fuad and Su (2020) [], the increase in the use of the Internet and social networks as a consequence of social isolation and teleworking practices has led to an increase in searches for information on the COVID-19 pandemic. This has increased searches for videos on how to do things, encouraging innovation and commercial success online []. Thus, in line with the study by Casco (2020) [], it will be interesting to see whether the adoption of technology on a rapid scale due to the pandemic will break old habits. However, the pandemic has not only caused changes in the technological world, but also in consumer needs and purchasing behaviour, which have changed completely. In order to prevent infections, citizens have isolated themselves at home, so companies have focused on strengthening their online business through marketing innovations to ensure their survival [].

According to Sheth (2020) [], consumer habits are transformed by changing circumstances. In this context, companies need to be attentive to changes in habits, because as Kotler (2020) [] explains, the pandemic has given rise to the anti-consumerism movement in the consumer sector, which seeks to simplify life, protect the environment and promote healthier eating, in other words, to reduce consumerism in order to free human beings from the superfluous and take care of the planet, awakening a new lifestyle, “Do I really need this?”.

On the other hand, according to Teixeira (2020) [], from 2020 onwards, there was a great adherence to e-commerce, essentially due to the pandemic caused by COVID-19 and the state of emergency decreed.

Since then, the number of Portuguese consuming online has increased []. According to the 2020 Global Digital Report, 65% of Portuguese people have bought a product online, and of those purchases made via the digital medium, only 33% of Portuguese people bought via their mobile phone, while 43% used their computer. However, 88% of the Portuguese population has searched online for a product to buy. The main reasons for this technological evolution, prior to the pandemic, are essentially related to Internet access, the use of social networks, the emergence of smartphones and constant innovations in logistics [].

In this way, all these technological developments have been included in consumers’ consumption habits, boosting business opportunities in e-commerce (Gunasekaran, Marri, McGaughey & Nebhwani, 2002) [].

- Consumption and Consumer Behaviour

Although this study focuses on the factors that may influence purchasing or consumption behaviour in the context of sustainable fashion, it would be appropriate to approach the subject of consumer behaviour in a general context before specifying. The aim is to gain an essential understanding of the different methods used to make purchasing decisions and the factors that most affect consumer behaviour and purchasing intentions.

The subject of consumer behaviour can be introduced as an area of study covering different disciplines, since it is influenced by different sciences. Based on Pivetta et al. (2020) [], various economists gave rise to the first studies on consumer behaviour, such as Adam Smith, who considered human needs to be innate and consumption decisions to be rational, based on evaluating the usefulness of products.

In the 1980s, the study of consumers began to incorporate theories and concepts from various sciences, such as notions from Freudian psychology, with the aim of understanding the different psychological motivations behind consumption []. Since then, interest in studies in the area of consumer behaviour has grown considerably. According to data from the Web of Science database on publications on this subject, the number of studies tripled between 2007 and 2017 [].

The study of consumer behaviour aims to investigate the process by which people, groups and organisations choose, buy, use and discard goods, services, opinions or experiences to satisfy their needs and desires, and how it is influenced by various factors ranging from cultural and social to personal [].

Human beings consume not only for their basic needs, but also to create an identity []. Individuals as consumers make exchanges with other individuals or organisations to obtain what they want or need, as stated by marketing, social and organisational psychology experts Bagozzi et al. (2002); Howard and Sheth, (1969); Levitt (1960); Mccarthy (1982), cited by Sampaio and Gosling (2009) [].

In view of an increasingly dynamic scenario, there are many influences involved in consumer purchasing behaviour. This process leads consumers to define what (what, when, how much and where) to buy on a daily basis. Marketing experts are encouraged to find out how the process of influence and behaviour takes place. This has encouraged marketing experts to find out how the influence and decision process takes place. However, it is very complex to understand the reasons that lead them to buy, given that consumers can be influenced by different factors [].

The starting point for the purchasing process is defined as the moment when the consumer identifies a problem or a need. The consumer’s purchasing decision may also be influenced by some moderating effects, which relate to the consumer’s level of involvement with the product/service or brand [].

This being said, in order to conclude the theoretical collection of this study, we will now present the factors that influence purchase intentions in the context of this study, sustainable fashion.

2.4. Influencing Factors of Sustainable Fashion Purchase Intentions

This study aims to understand which factors most influence the intention to buy sustainable fashion through the relations between environmental concern, fashion consumer awareness and adaptation to the digital evolution.

- Environmental Concern

As mentioned by Kim and Choi (2005) [], collective concern about environmental issues has gradually increased, and this concern directly affects green shopping behaviour.

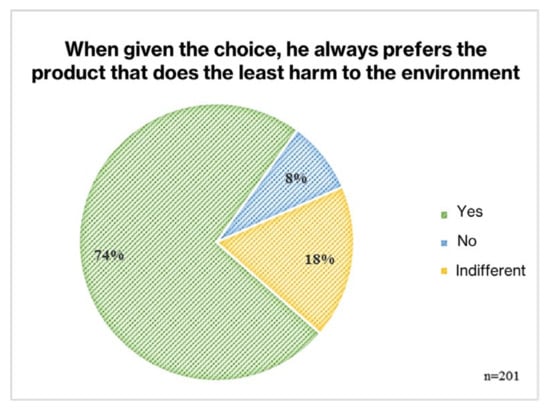

Environmental concern and ecological behaviours influence purchase intentions, since those who buy ecological products are naturally consumers who are aware of their environmental impact, and through their awareness contribute significantly to the interest in such products [].

A study carried out by BBC Global News reveals that 81% of consumers are committed to sustainability, adding value to brands, and that 79% say they consider the brand’s sustainability practices at the time of purchase []. The same study shows that most consumers (57%) would stop buying a product they are loyal to if they found out that it did not comply with sustainability standards. Also, within the scope of this study, it was found that globally, 46% of consumers say that helping the environment is essential for them and that they want the companies from which they buy products to be eco-friendly.

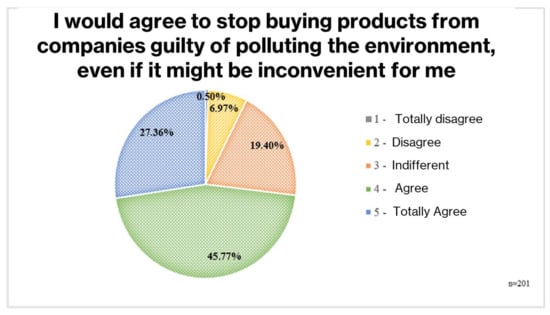

Increasingly, consumers are willing to change their purchase of products for ecological reasons and to stop buying products from companies that cause pollution. Like companies and other economic institutions, they are becoming increasingly aware of the importance of changing attitudes towards the development of their products in a conscious way, in relation to the impacts on the environment [].

- Environmental Awareness

Following the study of the reasons that may be based on the adoption of sustainable purchasing and consumption behaviours, sustainability-oriented consumers are referred to as environmentally conscious consumers, emphasising the relevance of environmental awareness in this process. According to Song, Qin and Yuan (2019) [], environmental awareness refers to consumers’ general beliefs, attitudes, and concerns regarding environmental issues. Thus, environmental awareness has a cognitive component based on knowledge and an affective component based on perception [].

According to Panni (2006), cited by Kaufmann et al. (2012) [], the more consumers are aware of social and environmental issues, the more they engage in pro-social and pro-environmental behaviours.

Through the research carried out by Song, Qin and Yuan (2019) [], it is confirmed that environmental awareness takes into account determinants of pro-environmental behaviour, from recycling behaviour to sustainable purchasing behaviours; the conclusion, according to other authors, is that consumers with greater environmental awareness are more likely to buy products based on their environmental requirements and social responsibility [].

In this context, the following research hypothesis was defined:

H1.

Environmental concern has a positive influence on fashion consumers’ sustainable behaviour intentions.

H2.

Environmental concern has a positive influence on sustainable behaviour intentions.

- Conscious Consumption

Within the focus of this study, it is important to investigate, on the one hand, how the context of sustainability is seen by consumers and, on the other hand, how consumers associate it with fashion; first we will address sustainable consumer behaviour in a generalised way.

According to Stancu et al. (2020) [], studies carried out with consumers state that they consider the concept of sustainability to be complex, revealing incoherence and confusion regarding its interpretation, and tend to relate it mainly to environmental aspects, while social and economic aspects are less stressed.

However, Stringer et al. (2019) [] describe that, in most consumers, there is a growing awareness of the importance of the concept of sustainability.

While Portilho (2010), cited by Pivetta et al. (2020) [], exemplifies it as a consumer who, in addition to the quality/price variable, encompasses in the influencing factors of their choices the environmental variable, choosing products that are not aggressive to the environment, considering their impact on the physical environment, purchasing ecological products to minimize the potentially negative environmental impact.

On the other hand, Webster (1975), cited by Calderon-Monge et al. (2020) [], introduces the concept of a socially conscious consumer, referring to one who takes into account the public effects of their private consumption or who tries to use their purchasing power with the aim of bringing about social change, showing himself to be aware of social problems, and believing that it can make a difference.

According to McNeill and Moore (2015) [], people are becoming more aware of their social responsibilities, and more concerned about the impact their consumption behaviours will have on the world. According to Easey (2009) [], this type of consumer is used to thinking before buying, that is, buying only what he/she really needs, in all fields of consumption. Ottman (1997) [], on the other hand, states that the green consumer is the one who has a purchasing behaviour that evaluates the products and services according to the environmental responsibility of the producers and the functional performance and price of the product.

However, this is a secondary need of these consumers, according to Maslow’s pyramid [], because regardless of being sensitive to the environmental performance component of products, it is expected that many purchasing decisions will fall on products with lower environmental performance.

Kohlrausch et al. (2004) [] point out that the consumer has little information regarding the attributes of the products, namely the raw materials and technologies that have been used, which leads to the fact that many purchasing decisions are based on products with better environmental performance.

Proença and Paiva (2011) [] state that it is not enough for companies to promote indications such as “environmentally friendly”, “organic” or “natural”, because the consumer is usually suspicious of this information, and it is necessary to provide enough information for the comparison between alternative products.

Within the framework of the characterisation of green consumers, Ottman (1997) [] defined five consumer segments in relation to environmental issues, cited by Sá (2021) []:

- -

- 1st, True-blue greens—these are people who believe they can make a difference in favour of environmental sustainability and have ecologically correct consumption behaviour.

- -

- 2nd, Greenback greens—they consider that they do not have time to dedicate themselves to the environmental cause and are not socially and politically active, but have correct consumption behaviour.

- -

- 3rd, Sprouts—their main pro-environmental activity is recycling; although they want to join other types of activities, they only do this when they do not require much effort.

- -

- 4th, Grousers—they are a confused and uninformed group; they do not believe that they can do anything meaningful in favour of the environment, thinking that it is the responsibility of governments and big companies.

- -

- 5th, Basic Browns—they are indifferent and do not believe that the environmental problems are very serious.

According to some research (Boztepe, 2012; Chen and Chai, 2010; Gan et al., 2008; Kaufmann et al., 2012; Kianpour et al., 2012; Laroche et al., 2001; Paço et al., 2009; Ramly et al., 2012), cited by Ferreira (2013) [], the characteristics that best define the sociodemographic profile of the green consumer are the following:

- -

- Gender;

- -

- Age;

- -

- Number of children;

- -

- Level of education;

- -

- Income.

Although each author and each study has its own particularity, the variables “Gender” and “Buying Behaviour” are in a positive relationship, according to Boztepe, 2012; Darnall et al., 2012; Ramly et al., 2012; Straughan and Roberts, 1999, cited by Ferreira (2013) []. Generally, men tend to have greater knowledge of environmental issues than women, and women are more likely to buy green products and participate more frequently in several types of green behaviour (e.g., recycling and conservation of energy and resources) [].

In turn, in older studies, Straughan and Roberts (1999) [] concluded that age and ecological knowledge are relevant factors in triggering people to buy “more environmentally friendly” products. The same authors also showed that income and education have a considerable influence on eco-conscious consumers.

Thus, the level of education has a positive relationship with purchasing behaviour, as it is possible to state, according to several authors [,], that those who have qualifications corresponding to higher education, and consequently, greater ease of access to information, show greater concern and act in line with the preservation of the environment, being more likely to buy green products than consumers who have a low level of education. According to Tama, Cüreklibatir and Öndoǧan (2017) [], consumers who hold a master’s degree are the ones who attribute the most interest to the purchase of sustainable clothing, and this type of consumer would accept the need to pay more for these garments.

At the same time, studies carried out by Saricam, Erdumlu, Silan, Dogan and Sonmezcan (2017) [] record that the level of environmental awareness increases proportionally with the level of consumer education. According to the same authors, it was concluded that the relationship between environmental concern and income shows that those who have greater environmental concern also have higher levels of income. Another study, carried out by Kaufmann et al. (2012) [], points out that the lack of income makes it impossible for them to consume green products or to do so more often.

According to Ottman (1997) [], green consumers are usually individuals with a high level of education, with an average age of 37 years, employed, and usually in executive functions. However, even with an increase in consumer awareness and interest in sustainable products, a relevant part of the studies consulted by Lee et al. (2020) [] indicate that there is a marked divergence between the importance attributed by consumers to sustainability and their purchasing behaviours.

Following this, a study carried out by the United Nations Global Compact (UN Global Compact), United Nations Environment Programme and Utopies (2005) [] confirms that 40% of consumers say they are willing to buy real products, but only a minority (4%) say they actually buy these products. At the same time, in Portugal, the authors Paço and Raposo (2009) [] confirm that the Portuguese understand the ecological challenges that are currently being observed, as well as the existence of environmental problems; however, their concerns are not always transposed into behaviours.

In this sense, through a study, Vaccari et al. (2016) [] reached similar conclusions, by finding factors that increase the discrepancy between the importance attributed to sustainability and sustainable behaviours, which are the following:

- -

- Lack of appropriate outlets;

- -

- Lack of information and legal regulations;

- -

- Lack of knowledge of the origin of resources;

- -

- Negative perceptions of products (e.g., appearance).

In this way, the authors, in the context of their study, presented factors that contribute to the reduction of this gap, and examples are health concerns and positive perceptions about the products [].

- Fashion Consumer Awareness

According to Zhang and Dong (2020) [] regarding “green purchasing behaviour”, it is mentioned as a rational behaviour of consumers to protect the environment with effort on the part of their personal interests. However, when it comes to the consumption of fashion items, including clothing and accessories, it must be kept in mind that consumers are faced with products that have an important social relevance because they are visible to others [].

The question, therefore, arises as to whether the motives implicit in the purchase of sustainable fashion products can be linked solely to genuine environmental protection interests. Kozar and Connell (2014) [] argue that consumers are more interested in environmental issues compared to social issues in the field of fashion.

In turn, Soyer, Rotterdam, Dittrich, Kooy and Rotterdam (2019) [] state that concern for the environment is the biggest driver of sustainable shopping in the fashion industry. In this way, positive relationships can be found between knowledge and attitudes towards environmental issues linked to fashion and ecologically responsible buying behaviour. Given that environmental concern has a positive effect on sustainable consumption, it is implied that buying sustainable fashion items is a sign that consumers understand the negative impacts they can have on the environment []. The relation between a pro-environment attitude and the consumption of sustainable fashion is expressive and positive; the more consumers have the attitude of protecting the natural habitat through their actions, the more they engage in sustainable fashion.

In this way, consumers who are genuinely interested in environmental issues are influenced in their choices by the following aspects: local or ethical production, environmentally friendly materials and long-lasting products [].

Wagner and Heinzel (2020) [] state that the lack of awareness of sustainability continues to be indicated as one of the most important barriers to ethical fashion consumption. Therefore, in order to raise consumer awareness and behaviour, there needs to be greater accessibility of products in terms of points of sale, as well as an exhibition of stories, transmitting information about the origin of the resources used, a method that has been proven in several cases.

However, most fashion consumers do not sacrifice their fashion needs and desires for the sake of sustainability, and the existence of this gap between consumers’ attitudes towards sustainability and their eco-friendly behaviour ultimately creates a state of psychological imbalance [].

In reality, according to Calderon-Monge et al. (2020) [], consumers are the final link in the value chain, as they can set trends and establish preferences, while encouraging, rejecting or diverting the purchase of products, brands, formats or other attributes, including ethical, social, and environmental appreciations, and will use this power in proportion to the knowledge they have. According to the authors, the literature provides definitive evidence of the positive relation between the perceived effect of consumers’ behaviours and sustainable purchasing behaviours [].

Following this idea, at the fashion level, according to Mintel (2017), cited by Goworek et al. (2020) [], consumer demand for sustainable clothing is increasing. Rijo (2021) [] found that the majority of consumers prefer greener fashion brands, particularly those aged 16–24 (Generation Y or Millennials and Generation Z), perhaps because they are more likely to have been educated about climate change and its potential impact on their generation, highlighting their level of environmental awareness.

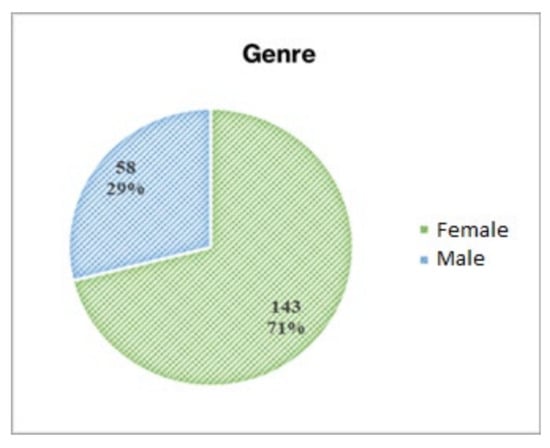

Another study perspective, according to Niinimäki (2011) [], indicates that the female gender is the group most concerned with environmental and ethical issues in the fashion industry, and women ascribe more value to the purchase of ecological clothes, preferring to buy clothes that provide lasting and comfortable use, according to Tama, Cüreklibatir Encan and Öndoǧan (2017) []. However, it must be considered that most sustainable fashion consumers are women, when compared to the male gender []; they also consume other environmentally friendly products more.

Wagner and Heinzel (2020) [] reinforce, through their studies, the growing inclinations of consumers towards the recycling of textile waste and sustainable solutions, such as circular clothing, as well as the demand for more apparent and concrete information, including the environmental impacts of textile production, i.e., the demand for transparency of brands, both environmentally and socially. These authors also state that consumer attitudes are positive towards circular products, such as recycled or upcycled products.

- Sustainable Fashion Consumers’ Habits and Motivations

Most of the sustainable fashion buying behaviours are based on a set of distinct motivations that can complement each other, with a strong presence of financial benefits, and few individuals are intimately motivated to engage in sustainable behaviours.

In this sense, Hosta and Zabkar (2016), cited by Calderon-Monge et al. (2020) [], state that economic factors are the basis of responsible consumer behaviour, confirming the importance that these aspects have in their purchasing decisions, even if reinforced with other aspects. For example, according to studies carried out by several authors [], in this context, donation behaviours for recycling or selling unwanted clothes are motivated by financial benefits in the form of money or discounts for new purchases in the store where one donates, exposing external motivation. However, the donation of clothes can also be linked to the values of the individual, exposing an internalized motivation, when it is based on interest in others, intending to contribute to the satisfaction of people with fewer resources, to the protection of the environment or to a sense of civic duty.

According to a study of the factors that motivated the disposal of clothes, Joung and Park-Poaps (2013) [] concluded that those who want to save money resell or reuse their clothes and those who seek convenience in the act of buying tend to throw them in the trash; those who donate used clothes are motivated by environmental and charitable concerns, as well as being influenced by their families. However, the sentimental value that clothing may demonstrate is another factor to be considered when deciding to dispose of it, and people are more likely to donate clothes with high sentimental value to friends or family, and only then to charity []. Also, according to the authors, consumers can think of clothes as investments, if they have an emotional value, decreasing the frequency of disposal or recycling.

Isla (2013) [] mentioned that the sale of used clothes opens space for new pieces, and, thus, people get rid of the guilt of excessive or unnecessary consumption. In this way, it is considered that internalized habits and motivations have the potential to lead to persistent behaviours and future sustainable behaviours [].

- Decision-Making Criteria in Fashion Acquisition

There are few studies that clarify, with certainty, which of the criteria have more weight in the act of consumption, either for fashion consumers in general or for sustainable fashion consumers. What is known is that the most relevant variables related to products in the purchase of ethical clothing are price; quality; clothing style; product information and availability []. However, Solomon (2008) [] states that consumers are looking for quality and value at the same time, stating that the perception of quality is linked to satisfaction or dissatisfaction with a product/service.

Accordingly, several studies articulate quality and price as important conditions in the purchase of clothing by the consumer [].

On the other hand, most practical studies related to quality have focused on price as the main factor for determining the quality of products. However, price is only one of several useful extrinsic factors, since the brand can be as important or more important than price [], because consumers use both price and brand as indicators of quality [].

According to a study carried out by Garretson et al. (2002) [], consumers of fashion and clothing products are loyal to brands and exhibit a great tendency to buy the usual brands, so it is unlikely that they will opt for new brands or brands that they do not know.

Macdonald and Sharp (2000) [] further demonstrate the effect of brand awareness on purchasing decisions; similarly, Laroche et al. (1996) [] asserted that the familiarity with one brand has an influence on consumer confidence in another brand, which in turn affects purchase intention. Certain authors have disclosed through a study that the product (design and durability), the price (resources spent) and the novelty (sharing and influences) of the articles were considered the most important criteria when buying clothing, while the origin of the product was the least considered [].

Consumers who consider themselves to be more knowledgeable about these issues and who take action on them are willing to pay premium prices as a way of cooperating for environmental protection, and are increasingly aware of and open to these types of issues []. However, even if socially and environmentally responsible ventures convince consumers to spend more money [], it is reported that consumers are more likely to spend a higher amount when it comes to socially responsible fashion than environmentally responsible fashion.