Improving Quality of Work for Positive Health: Interaction of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 8 and SDG 3 from the Sustainable HRM Perspective

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis

2.1. Work Practices-Related Leading Indicators of Health for Social Sustainability

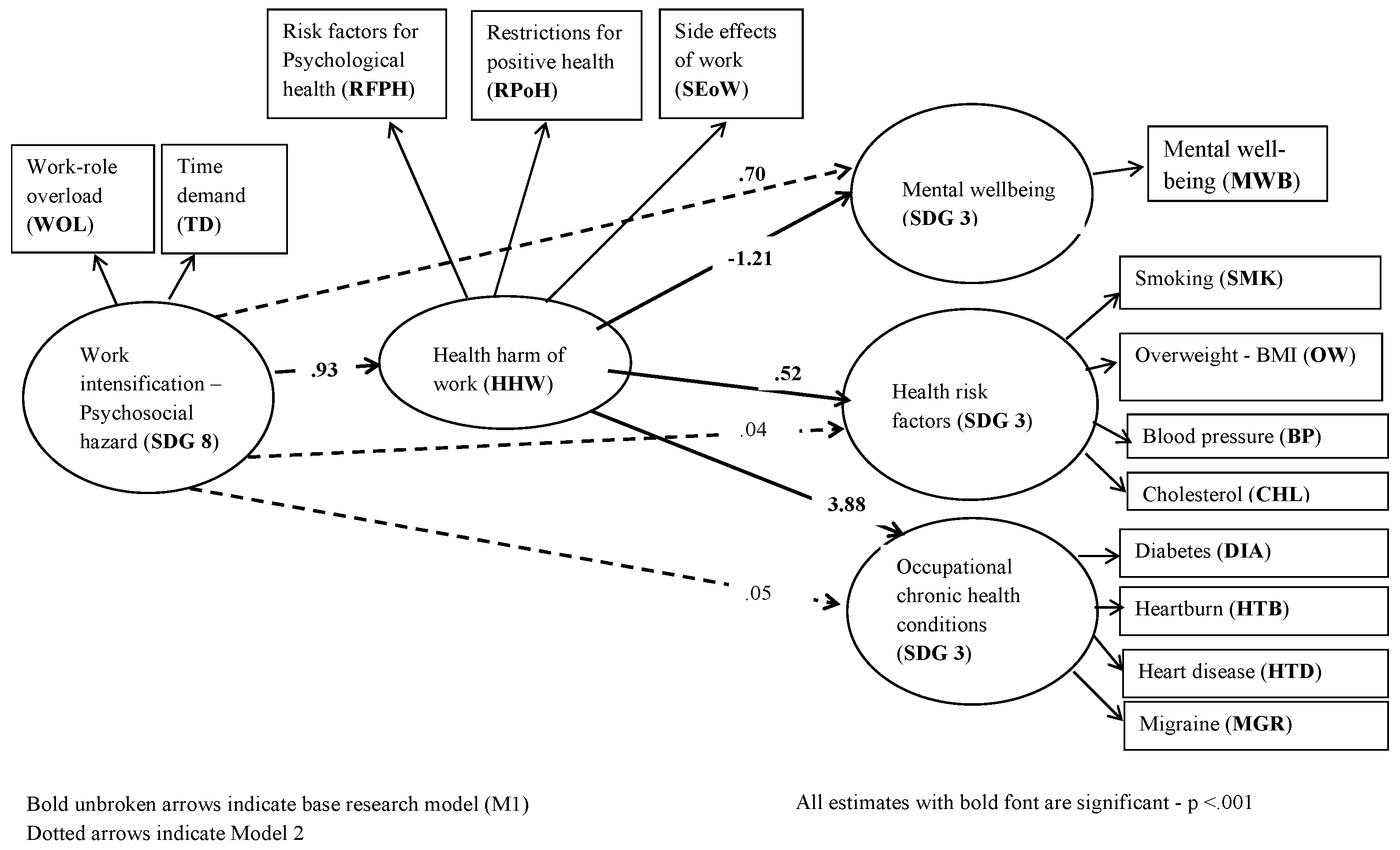

2.2. Work Intensification and Health Outcomes: The Role of the Health Harm of Work

2.3. Work Intensification as Decent/Adverse Working Conditions (SDG 8)

2.4. Work Intensification and Self-Reported Health Outcomes

2.5. Health Harm of Work as a Mediator

3. Research Method

Sample and Procedure

4. Measures

4.1. Independent Variable: Work Intensification

4.2. Mediator Variable: The Health Harm of Work

4.3. Dependent Variable: Mental Well-Being

4.4. Dependent Variable: Health Risk Factors

4.5. Dependent Variable: Work-Related Chronic Disease

5. Data Analyses

5.1. Measurement Models

5.2. The Research Model for Testing Hypotheses

6. Results

6.1. Research Model Assessment

6.2. Structural Model Assessment

7. Discussion

8. Limitations, Future Research, and Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Work Intensification

- Strongly disagree

- Disagree

- Slightly disagree

- Neither agree nor disagree

- Slightly agree

- Strongly agree

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Work-role overload—items 1–6; Time demands—items 7–10. | ||||||

Appendix A.2. Health Harm of Work

- Strongly disagree (SD)

- Moderately disagree (MD)

- Slightly disagree (SD)

- Slightly agree (SA)

- Moderately agree (MA)

- Strongly agree (SA)

| Harm of Work Practices on Employee Well-Being Outcomes | SD | MD | SD | SA | MA | SA |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Risk factors for psychological health (RFPH)—items 1, 6, 8, 9, 11, and 13. Restrictions for positive health (RPoH)—items 2, 7, 10, and 12. Side effects of work (SEoW)—items 3, 4, 5, and 14. | ||||||

Appendix A.3. Mental Well-Being

- Strongly disagree (SD)

- Moderately disagree (MD)

- Slightly disagree (SD)

- Slightly agree (SA)

- Moderately agree (MA)

- Strongly agree (SA)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

Appendix A.4

- (A)

- Health risk factors

- Please indicate your height _____ meters; Weight ______ Kg

- Are you a smoker? 1 (No) 2. (Yes)

- If yes, how many cigarettes do you smoke in a day: 1 (<10) 2 (10 and more)

- Blood pressure

- Reported systolic/diastolic blood pressure >139/>89 mmHg or currently have high blood pressure.

- Currently take medication for blood pressure

- Currently under medical care for blood pressure

- Cholesterol

- Reported total cholesterol >239 mg/dL or currently have high cholesterol.

- Currently take medication for cholesterol

- To work out your BMI:

- divide your weight in kilograms (kg) by your height in metres (m)

- then divide the answer by your height again to get your BMI

- For example:

- If you weigh 70 kg and you’re 1.75 m tall, divide 70 by 1.75. The answer is 40.

- Then divide 40 by 1.75. The answer is 22.9. This is your BMI.

Appendix A.5

- (B)

- Occupational chronic health conditions

- Never

- In the past

- Have currently

| Condition | Never | In the Past | Have Currently | If Responded to “3”, Are under Medical Care and/or Medication | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 (Yes) | 2 (No) |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 (Yes) | 2 (No) |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 (Yes) | 2 (No) |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 (Yes) | 2 (No) |

References

- International Labour Organisation (ILO). WHO/ILO Joint Estimates of the Work-Related Burden of Disease and Injury, 2000–2016: Global Monitoring Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bloomberg, M.R.; Aggarwala, R.T. Think locally, act globally. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2008, 35, 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, O.; Somerville, C.; Suggs, L.S.; Lachat, S.; Piper, J.; Aya Pastrana, N.; Beran, D. The process of prioritization of non-communicable diseases in the global health policy arena. Health Policy Plan. 2019, 34, 370–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; Montiel, I.; Husted, B.W.; Balarezo, R. The Grand Challenge of Human Health: A Review and an Urgent Call for Business–Health Research. Bus. Soc. 2022, 61, 1353–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howden-Chapman, P.; Siri, J.; Chisholm, E.; Chapman, R.; Doll, C.N.; Capon, A. SDG 3: Ensure healthy lives and promote wellbeing for all at all ages. In A Guide to SDG Interactions: From Science to Implementation; International Council for Science: Paris, France, 2017; pp. 81–126. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer, J. Dying for a Paycheck: How Modern Management Harms Employee Health and Company Performance—And What We Can Do about It; HarperCollins: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mariappanadar, S. Stakeholder harm index: A framework to review work intensification from the critical HRM perspective. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2014, 24, 313–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, R.; O’Keeffe, V.; Leka, S.; Webber, M.; Dollard, M. Analytical review of the Australian policy context for work-related psychological health and psychosocial risks. Saf. Sci. 2019, 111, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwetsloot, G.; Leka, S.; Kines, P.; Jain, A. Vision zero: Developing proactive leading indicators for safety, health and wellbeing at work. Saf. Sci. 2020, 130, 104890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinelnikov, S.; Inouye, J.; Kerper, S. Using leading indicators to measure occupational health and safety performance. Saf. Sci. 2015, 72, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granter, E.; McCann, L.; Boyle, M. Extreme work/normal work: Intensification, storytelling and hypermediation in the (re) construction of ‘the New Normal’. Organization 2015, 22, 443–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rydstedt, L.W.; Ferrie, J.; Head, J. Is there support for curvilinear relationships between psychosocial work characteristics and mental well-being? Cross-sectional and long-term data from the Whitehall II study. Work Stress 2006, 20, 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariappanadar, S. Health harm of work from the sustainable HRM perspective: Scale development and validation. Int. J. Manpow. 2016, 37, 924–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macke, J.; Genari, D. Systematic literature review on sustainable human resource management. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 208, 806–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, R.; Bozionelos, N.; Zhou, W.; Newman, A. High-performance work systems and key employee attitudes: The roles of psychological capital and an interactional justice climate. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2021, 32, 443–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GRI 403; Occupational Health and Safety 2018. GRI: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018.

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearl, J. The causal foundations of structural equation modelling. In Handbook of Structural Equation Modelling, 2nd ed.; Hoyle, R.H., Ed.; The Guildford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Latza, U.; Hampel, E.; Wiencke, M.; Prigge, M.; Schlattmann, A.; Sommer, S. Introducing occupational health management in the German Armed Forces. Health Promot. Int. 2017, 33, 938–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, A.; Leka, S.; Zwetsloot, G.I.J.M. Aligning Perspectives and Promoting Sustainability. In Managing Health, Safety and Well-Being. Aligning Perspectives on Health, Safety and Well-Being; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherland, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariappanadar, S. Sustainable Human Resource Management: Strategies, Practices and Challenges; Macmillan International Publisher: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mariappanadar, S. Do HRM systems impose restrictions on employee quality of life? Evidence from a sustainable HRM perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 118, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariappanadar, S.; Kramar, R. Sustainable HRM: The Synthesis Effects of High Performance Work Systems on Organisational Performance and Employee Harm. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2014, 6, 206–224. [Google Scholar]

- Macky, K.; Boxall, P. High-involvement work processes, work intensification and employee well-being: A study of New Zealand worker experiences. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2008, 46, 38–55. [Google Scholar]

- Ogbonna, E.; Harris, L.C. Work intensification and emotional labour among UK university lecturers: An exploratory study. Organ. Stud. 2004, 25, 1185–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamerāde, D.; Wang, S.; Burchell, B.; Balderson, S.U.; Coutts, A. A shorter working week for everyone: How much paid work is needed for mental health and well-being? Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 241, 112353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silla, I.; Gamero, N. Shared time pressure at work and its health-related outcomes: Job satisfaction as a mediator. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2014, 23, 405–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouter, A.C.; Bumpus, M.F.; Head, M.R.; McHale, S.M. Implications of overwork and overload for the quality of men’s family relationships. J. Marriage Fam. 2001, 63, 404–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van De Voorde, K.; Paauwe, J.; Van Veldhoven, M. Employee well-being and the HRM–organizational performance relationship: A review of quantitative studies. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2012, 14, 391–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsay, H.; Scholarios, D.; Harley, B. Employees and high-performance work systems: Testing inside the black box. Br. J. Ind. Relat. 2000, 38, 501–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Zapata, O.; Pascual, A.S.; Álvarez-Hernández, G.; Collado, C.C. Knowledge work intensification and self-management: The autonomy paradox. Work Organ. Labour Glob. 2016, 10, 27–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Härmä, M. Workhours in relation to work stress, recovery and health. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2006, 32, 502–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urtasun, A.; Nuñez, I. Healthy working days: The (positive) effect of work effort on occupational health from a human capital approach. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 202, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grace, M.K.; Van Heuvelen, J.S. Occupational variation in burnout among medical staff: Evidence for the stress of higher status. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 232, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quandt, S.A.; Arcury-Quandt, A.E.; Lawlor, E.J.; Carrillo, L.; Marín, A.J.; Grzywacz, J.G.; Arcury, T.A. 3-D jobs and health disparities: The health implications of latino chicken catchers′ working conditions. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2013, 56, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huppert, F.A.; So, T.T. Flourishing across Europe: Application of a new conceptual framework for defining well-being. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 110, 837–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P.E.; Cooper, C.L.; Poelmans, S.; Allen, T.D.; O’driscoll, M.; Sanchez, J.I.; Siu, O.L.; Dewe, P.; Hart, P.; Lu, L.; et al. A cross-national comparative study of work-family stressors, working hours, and well-being: China and Latin America versus the Anglo world. In International Human Resource Management; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 257–277. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, G.L. Families in the media: Reflections on the public scrutiny of private behavior. J. Marriage Fam. 1999, 61, 821–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivimäki, M.; Jokela, M.; Nyberg, S.T.; Singh-Manoux, A.; Fransson, E.I.; Alfredsson, L.; Virtanen, M. Long working hours and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis of published and unpublished data for 603 838 individuals. Lancet 2015, 386, 1739–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuit, A.J.; van Loon, A.J.M.; Tijhuis, M.; Ocké, M.C. Clustering of lifestyle risk factors in a general adult population. Prev. Med. 2002, 35, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraemer, H.C.; Kazdin, A.E.; Offord, D.R.; Kessler, R.C.; Jensen, P.S.; Kupfer, D.J. Coming to terms with the terms of risk. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1997, 54, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flay, B.R.; Petraitis, J. A new theory of health behavior with implications for preventive interventions. Adv. Med. Sociol. 1994, 4, 19–44. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Hulst, M. Long workhours and health. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2003, 29, 171–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrie, J.E. Is job insecurity harmful to health? J. R. Soc. Med. 2001, 94, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeytinoglu, I.U.; Denton, M.; Davies, S.; Baumann, A.; Blythe, J.; Boos, L. Associations between work intensification, stress and job satisfaction: The case of nurses in Ontario. Relat. Ind. 2007, 62, 201–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heraclides, A.; Chandola, T.; Witte, D.R.; Brunner, E.J. Psychosocial stress at work doubles the risk of type 2 diabetes in middle-aged women evidence from the whitehall II study. Diabetes Care 2009, 32, 2230–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothenbacher, D.; Peter, R.; Bode, G.; Adler, G.; Brenner, H. Dyspepsia in relation to Helicobacter pylori infection and psychosocial work stress in white collar employees. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1998, 93, 1443–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, M.; Heikkilä, K.; Jokela, M.; Ferrie, J.E.; Batty, G.D.; Vahtera, J.; Kivimäki, M. Long working hours and coronary heart disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2012, 176, 586–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnentag, S.; Kuttler, I.; Fritz, C. Job stressors, emotional exhaustion, and need for recovery: A multi-source study on the benefits of psychological detachment. J. Vocat. Behav. 2010, 76, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.L.; Sonnentag, S.; Jimmieson, N.L.; Newton, C.J. Relaxation during the evening and next-morning energy: The role of hassles, uplifts, and heart rate variability during work. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2020, 25, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donahue, E.G.; Forest, J.; Vallerand, R.J.; Lemyre, P.N.; Crevier-Braud, L.; Bergeron, É. Passion for work and emotional exhaustion: The mediating role of rumination and recovery. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2012, 4, 341–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voegtlin, C.; Greenwood, M. Corporate social responsibility and human resource management: A systematic review and conceptual analysis. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2016, 26, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selye, H. Stress and disease. Science 1955, 122, 625–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O′Connor, D.B.; Thayer, J.F.; Vedhara, K. Stress and health: A review of psychobiological processes. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2021, 72, 663–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bannai, A.; Tamakoshi, A. The association between long working hours and health: A systematic review of epidemiological evidence. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2014, 40, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bech, P.; Olsen, L.R.; Kjoller, M.; Rasmussen, N.K. Measuring well-being rather than the absence of distress symptoms: A comparison of the SF-36 Mental Health subscale and the WHO-Five well-being scale. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2003, 12, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.J.; Bates, P. Measuring health-related productivity loss. Popul. Health Manag. 2011, 14, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cundiff, J.M.; Smith, T.W.; Uchino, B.N.; Berg, C.A. Subjective social status: Construct validity and associations with psychosocial vulnerability and self-rated health. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2013, 20, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective; Pearson Publisher: Delhi, India, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan, A. A review of eight software packages for structural equation modeling. Am. Stat. 2012, 66, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Lynch, J.G., Jr.; Chen, Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Kelley, K. Effect size measures for mediation models: Quantitative strategies for communicating indirect effects. Psychol. Methods 2011, 16, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmgren, K.; Dahlin-Ivanoff, S.; Björkelund, C.; Hensing, G. The prevalence of work-related stress, and its association with self-perceived health and sick-leave, in a population of employed Swedish women. BMC Public Health 2009, 9, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rindfleisch, A.; Malter, A.J.; Ganesan, S.; Moorman, C. Cross-sectional versus longitudinal survey research: Concepts, findings, and guidelines. J. Mark. Res. 2008, 45, 261–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinpoor, A.R.; Bergen, N.; Schlotheuber, A.; Grove, J. Measuring health inequalities in the context of sustainable development goals. Bull. World Health Organ. 2018, 96, 654–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Testing for multigroup invariance using AMOS graphics: A road less travelled. Struct. Equ. Model. 2004, 11, 272–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Models | χ2 (df) | GFI | CFI | TLI | IFI | RMSEA | χ2diff | dfdiff |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full measurement model, six factors | 575.29 (179) | 0.90 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.07 | ||

| Model A, five factors (time demand and work overload are combined into a single factor) | 2375.30 (254) | 0.88 | 0.80 | 0.82 | 0.80 | 0.94 | 1800.00 | 75 *** |

| Model B, four factors (three health harm dimensions are combined into a single factor) | 2271.24 (260) | 0.71 | 0.62 | 0.56 | 0.62 | 0.14 | 1795.95 | 81 *** |

| Model C, four factors (time demand, work overload, and mental well-being are combined into a single factor) | 3208.40 (270) | 0.59 | 0.44 | 0.38 | 0.45 | 0.17 | 2633.11 | 91 *** |

| Model D, three factors (three health harm dimensions and mental well-being combined into a single factor) | 2805.42 (272) | 0.64 | 0.52 | 0.47 | 0.52 | 0.16 | 2230.13 | 93 *** |

| Model E, one factor (all variables combined into a single factor) | 3642.66 (278) | 0.57 | 0.36 | 0.31 | 0.36 | 0.18 | 3067.37 | 99 *** |

| Binary Variable | Low | High | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metric Variable | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| 1. OW a | 310 (76.5) | 95 (23.5) | ||||||||||||||

| 2. SMK a | 340 (84) | 65 (16) | 0.07 | |||||||||||||

| 3. BP a | 362 (89.4) | 43 (10.6) | 0.13 | −0.03 | ||||||||||||

| 4. CHL a | 360 (88.9) | 45 (11.1) | 0.06 | −0.06 | 0.35 | |||||||||||

| 5. DIA a | 377 (93.1) | 28 (6.9) | 0.14 | 0.12 | −0.83 | 0.23 | ||||||||||

| 6. HTB a | 288 (71.1) | 117 (28.9) | 0.19 | −0.04 | 0.18 | −0.12 | 0.20 | |||||||||

| 7. HTD a | 395 (97.5) | 10 (2.5) | 0.08 | 0.21 | −0.97 | −0.88 | 0.90 | 0.96 | ||||||||

| 8. MGR a | 328 (81) | 77 (19) | 0.25 | 0.08 | −0.16 | 0.11 | 0.62 | 0.49 | 0.98 | |||||||

| 9. WOL b | 4.15 | 1.34 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.19 | 0.32 | 0.32 | −0.03 | −0.26 | −0.02 | ||||||

| 10. TD b | 4.35 | 1.74 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.20 | 0.07 | −0.23 | −0.38 | 0.05 | 0.36 | |||||

| 11. RFPH b | 3.13 | 1.12 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.14 | 0.45 | 0.14 | 0.59 | 0.58 | ||||

| 12. RPoH b | 3.57 | 1.15 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.28 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.48 | −0.11 | 0.58 | 0.51 | 0.64 | |||

| 13. SEoW b | 2.69 | 1.03 | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.21 | −0.01 | 0.15 | 0.23 | −0.09 | 0.06 | 0.58 | 0.36 | 0.63 | 0.34 | ||

| 14. MWB b | 3.99 | 0.93 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.33 | 0.24 | 0.08 | −0.20 | −0.55 | −0.13 | −0.46 | −0.29 | −0.56 | −0.44 | −0.46 |

| Model | Chi Square | df | p | GFI | AGFI | RMSEA | NFI | CFI | IFI | Chi Square Difference | df |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | 693.77 | 109 | 0.00 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.11 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| M2 | 658.57 | 105 | 0.00 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.11 | 1 | 1 | 1 | M1–M2 = 35.20 *** | 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mariappanadar, S. Improving Quality of Work for Positive Health: Interaction of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 8 and SDG 3 from the Sustainable HRM Perspective. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5356. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16135356

Mariappanadar S. Improving Quality of Work for Positive Health: Interaction of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 8 and SDG 3 from the Sustainable HRM Perspective. Sustainability. 2024; 16(13):5356. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16135356

Chicago/Turabian StyleMariappanadar, Sugumar. 2024. "Improving Quality of Work for Positive Health: Interaction of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 8 and SDG 3 from the Sustainable HRM Perspective" Sustainability 16, no. 13: 5356. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16135356

APA StyleMariappanadar, S. (2024). Improving Quality of Work for Positive Health: Interaction of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 8 and SDG 3 from the Sustainable HRM Perspective. Sustainability, 16(13), 5356. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16135356