Abstract

The economic emigration of young people from rural areas in Poland, and in particular the emigration of young medical personnel, is a relatively little-recognized phenomenon. What distinguishes this study from many works on related topics is that the subject of the study is the tendency or desire to migrate itself, and not the study of the migration motives of people who have already emigrated. The main aim of the research was to identify the migration conditions of young nurses from rural areas. An additional goal was to determine the directions and types of foreign migrations and their impact on the competitiveness and sustainable development of the studied region. The research was conducted in five voivodeships of Eastern Poland among students at state medical universities. The research tool was a survey, the essence of which was to provide data on the purpose of migration of young people, chances of finding a job abroad, and identification of push and pull migration factors. Based on the logistic regression model, a number of factors were identified explaining the tendency to migrate, such as economic factors, gaining professional experience, and prospects. The influence of factors pushing migration should be reduced through state policy tools. The intensity of migration may significantly impact the sustainable development of healthcare in Poland in the near and distant future.

1. Introduction

It should be emphasized that the science of sustainable development concerns not only environmental protection but also economic and social aspects within a broader definition. Sustainable social goals include, among others, reducing poverty and inequality, enabling similar development opportunities for all the world’s inhabitants, integrating immigrants, and protecting the basic quality of life and human health. A socially sustainable society pays special attention to marginalized sectors (e.g., women and people of post-working age), education, and the promotion of mutual tolerance in a multicultural society. Work is considered the main way to improve the quality of life. Globalization is a challenge for the sustainable distribution of social development. In a global economy based on knowledge and innovation, it is particularly important to attract employees with the greatest capabilities [1].

One of the conditions for stable economic development is the sustainable development of agriculture and rural areas in general. Rural areas are areas with considerable population dynamics and significant social and spatial mobility [2]. Even though Poland is a country with a low age of people living in the countryside, it is a fact that rural areas are being depopulated, and especially young people are leaving them. In suburban villages, the number of inhabitants is increasing, while in typically agricultural villages there is a decrease. This trend of depopulation of rural areas is particularly visible in Eastern Poland. Rural peripheral areas are at real risk of depopulation. The main factor of this phenomenon is the lack of work and low wages, resulting in lower pro-family and procreative tendencies and social exclusion. Other factors include the demand–supply structural imbalance of jobs, lack of career and personal development opportunities, wage competition from attractive jobs, the difficult nature of work in the countryside, and the potentially shorter life expectancy. The occurrence of these factors will result in some consequences [3]. Areas struggling with depopulation will be significantly underinvested in by local taxes, which will translate into a weaker development of infrastructure and provision of services, especially medical ones. This will increase the spiral of further emigration, resulting in shortages in the labor market and other problems related to, for example, maintaining cultural heritage. All these changes increase the gap between urban and rural areas and cause regional imbalance [4].

The Schengen Agreement is of significant economic importance. Twenty-nine states are parties to it (25 European Union member states plus Iceland, Norway, Switzerland, and Liechtenstein). It allows for the elimination of controls at internal EU borders. Thus, it has a positive impact on economic migration, tourist traffic, and cross-border trade. The lack of internal border controls facilitates the flow of human capital and is therefore a factor encouraging migration.

Poland’s integration with the EU has become a great opportunity for change for peripheral areas that are lagging in socio-economic development. In the initial period (after 2004), Poles (including young people) emigrated to find work. Thousands, especially young people, found employment in Great Britain, Ireland, and then in Germany and other European countries. Some of them have already stayed there, and some have returned—in addition to monetary resources, bringing knowledge, new skills, and a new view of the world. In the years 2007–2018, it was observed that the differences in the income potential of rural communes in Eastern Poland, measured by the income of commune budgets per capita, were gradually equalized in relation to other regions. However, there are still significant differences in the economic potential between rural communes in Eastern Poland and other regions of the country and the EU [5].

The economic emigration of young people since 2004 has become a problem both nationally [6,7,8,9,10] and regionally. This particularly concerns areas with a large amount of emigration, i.e., voivodeships of Eastern Poland such as Podkarpackie [11], Podlaskie [12], and Warmian-Masurian [13] and those in other regions of the country such as Opole [14,15,16] and Lower Silesia [17].

Regions with a high population outflow are an interesting area of research. The Opole region is particularly well-researched. Numerous publications have analyzed both the factors [18,19], the effects [20], and the directions [21] of foreign migration of residents of this region, also taking into account students [21,22,23]. However, Eastern Poland is less explored in this respect. There are publications on this topic, for example, covering the Podkarpackie voivodeship [24], the Świętokrzyskie voivodeship [25], and the Warmian-Masurian voivodeship [26,27,28], but there are much fewer of them, especially those concerning trips abroad by young people from rural areas, e.g., [29]. In the analysis of trips abroad from peripheral areas (rural areas), it was observed that young people emigrate mainly to European economic centers, where they have a chance to better realize their plans and professional ambitions [10,30]. Emigrants also take into account their own and their relatives’ experiences with integration into the local labor market. Social and economic integration with urban or rural areas becomes extremely important in the acceptance and imagination of a destination abroad [31]. The research also shows that the migration outflow was especially characteristic of the smallest villages, contributing to a change in their demographic structures, including the aging of the population [32] and changes in the gender structure [33,34]. Some authors postulate that international migrations of young people living in rural areas allow for a more effective allocation of labor resources, previously trapped in peripheral regions [35,36,37].

The importance of the topic discussed can be found in theories regarding migration. For example, the prevailing view in neoclassical theories is that the principal reason for migration is “differentiation of net economic benefits, especially wages” [38]. If we additionally link it with potential unemployment and a potential change in the location of employment [39], we should agree with Kulischer [40] that migration movements are intended to equalize economic differences thanks to the influence of push and pull factors. The neoclassical Harris–Todaro model also assumed that wage differentiation generates migration (especially from the countryside to the city), and the theory of economic development [41] emphasized the importance of further development of the “export” of surplus labor to another, more developed economy. As Jandl points out [42], when analyzing economic migrations, both the supply of labor and the structure of labor demand should be taken into account. Waldinger [43], who studied the phenomenon of immigrants congregating in specific professions/industries, suggested that networks create the so-called social capital, provide information, minimize risk, and help find a job. Research on migration should take into account economic motives that “are determined by the economic demand for the labor of foreigners” [44]. In terms of political concepts, the most important thing is the possibility of free movement, because it should be seen as equalizing all inequalities.

Based on the law of gravity, Ravenstein [45] formulated the seven laws of migration. It has been observed, among other things, that women have a stronger tendency to migrate than men, as does the rural population compared to the urban population [46,47]. The above laws provided the basis for the push–pull theory and model created by Lee [48]. It was based on the assumption that humans are inherently immobile. Therefore, there must be a strong factor that will induce them to migrate.

Youth are the most mobile group [49]. The reasons for the migration of the young generation are different. Foreign migration is often perceived by young people from peripheral areas [50,51,52,53,54,55] and people with specific qualifications and skills (nurses) as a chance for a better life. In the case of women, the decision to migrate is often based on the presence of many factors and their interaction. Migration decisions seem to be a compromise between the adopted strategy of strengthening one’s social and family position and self-fulfillment and the responsibility for family-related duties, i.e., relational and emotional aspects [56].

The problem of emigration of nurses began to be noticed especially after 2004 [57,58,59,60,61,62,63]. One of the negative consequences of emigration is the shortage of staff [64,65]. Shortages in the medical services market, including among employed nurses, have been highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic. This is an even bigger problem because the number of nurses in Poland is already one of the lowest in Europe. According to the 2017 Report [66] and the OECD Health Data 2016 data contained therein, the number of nurses per 10,000 people in Poland was 5.2, while in the same period, it was 17.5 for Switzerland, 16.9 for Norway, 13.1 for Germany, 11.1 for Sweden, and 7.9 for Great Britain. This number should be within the OECD average of 9.4. The problem is deepened by the lack of generation replacement and foreign migration.

The actual scale of migration of Polish nurses is estimated, among others, based on the number of issued certificates confirming professional qualifications and based on information on recognized professional qualifications made available by the European Commission. The Chamber of Nurses and Midwives reported that in the years 2004–2020, 21,653 certificates were issued in Poland to recognize professional qualifications. These data indicate great interest in economic emigration. However, they do not reflect the actual scale of this phenomenon, because many nurses emigrate outside the EU without obtaining a certificate, where it is not recognized [67]. Furthermore, not all people who received them started working in their profession in EU countries. Some decided not to emigrate or took up a job abroad in other professions.

The analyzed literature on the subject shows that nurses with higher education are more willing to migrate [68], and the age of nurses emigrating from developed countries was lower than that from developing countries. As many as 60% of them were less than 34 years old [68,69].

Pal et al. [70] and Boros et al. [71] also detailed a very wide range of factors prompting migration. These included, apart from income, having a family and working environment, for example. They also identified factors influencing the migration decisions of healthcare workers in Hungary. In the context of the family, geographical distance and location were of key importance, while in the workplace, the greatest emphasis was placed on the atmosphere at work, which became the key push factor. A cross-sectional study on a sample of nearly 600 nurses working in Poland was conducted by Szpakowski et al. [72]. They showed high interest in long-term migration or even permanent migration, mainly to Germany, England, or Norway. The most common motivation for emigration was low salaries in the country of origin and the desire to improve working conditions. The authors drew attention to the effect of aging in the nursing profession, which does not ensure the sustainable development of healthcare in Poland. Similar conclusions were reached by Żuk et al. [73]. They presented the reasons for economic migration from Poland to Western EU countries and the effects of these migrations on the functioning of the healthcare system. The authors pointed to the unsustainability of the medical care system in Europe, which manifests itself in the demand for doctors and nurses from Central and Eastern Europe for Western EU countries and, therefore, a simultaneous decrease in access to healthcare in emigration countries. The problems of the Polish health service resulting in a potential migration threat for nurses and other medical staff are cited by Domagała [74,75]. The factors pushing people away from their country of origin are staff shortages, which result in excessive workload and burnout, too low wages, and administrative burdens. The most important pull factors in this group of employees are the possibility of obtaining higher earnings and better working conditions. However, the important push factors turned out to be limited professional advancement, stress at work, and low prestige of the profession. Health systems on other continents outside Europe are also struggling with the outflow of nurses to wealthier countries [76]. This work highlights several push factors, such as rich countries offering higher wages, lack of adequate education, wage imbalances, and lack of autonomy and respect in the workplace. Career development opportunities as a nurse in countries of immigration were presented in the work of Pressley et al. [77]. Other studies have shown how objective factors such as the COVID-19 pandemic influence nurses’ migration decisions. The work [78] uses gravity models to prove that the poor macroeconomic condition of a given country, manifested by a recession, significantly affects the loss of medical personnel.

The following article is part of the broader research on the migration of nursing students. A profile of the surveyed people, nursing students living in rural areas of Eastern Poland, was created. Analyzing the literature on the subject, no articles were found regarding the foreign migration of young nurses living in rural areas of Eastern Poland. Therefore, this work is an attempt to fill this research gap.

Additionally, research on student migration often analyzes factors influencing the decision to emigrate [8,28,79,80] as well as professional plans and directions for emigration, including nursing students [27,81]. Migration is perceived by young people as an easy and quick way to improve their life (financial) and professional situation [28]. As EU citizens, they are guaranteed the free movement of people within the freedoms of the free market [82]. Research conducted on nursing at the Medical University of Warsaw [67] showed that approximately 25% of respondents chose nursing as their field of study because they believed that after graduating, they would have a greater chance of finding a job abroad. Taking this into account, the following article also examines the tendency to migrate and migration plans (declared willingness to emigrate after completing studies and direction of emigration after completing studies).

Moreover, to identify and assess the reasons for migration decisions made by nurses from rural areas entering the labor market, it is justified to study the factors influencing the decision to leave the country among students completing their education.

To sum up, economic trips abroad for young nurses from rural areas are an important problem because the costs of their education are borne by the Polish state (full-time studies are free of charge in Poland), but the benefits will be reaped by the countries to which they emigrate (performing work, paying taxes, etc.). Additionally, they have specialized qualifications also sought after in the domestic labor market. Currently, the profession of nurse in many voivodeships is on the list of shortage professions, especially when it comes to specialized nurses. A large number of emigrants increases the shortage of nurses in the Polish labor market [67].

The research was conducted in five voivodeships of Eastern Poland. These areas are characterized by a poor socio-economic situation not only in comparison to the rest of Poland but also to the EU and by a large outflow of inhabitants. The problem of young nurses going abroad is important because it affects not only demographic changes (including the aging of the population and decline in natural and actual growth) but also economic changes (including shortages in the industry labor market and reduced income from donations). Additionally, a consequence of the aging of the world’s population [83] is the increase in the demand for nursing care [84]. Therefore, having an appropriate number of nurses in a given region increases its attractiveness and competitiveness.

2. Materials and Methods

The main aim of the research was to identify and assess the causes of foreign emigration of young nurses from rural areas. An additional goal was to determine the directions and types of foreign migrations and their impact on the competitiveness and sustainable development of the studied region. The research was conducted in five voivodeships of Eastern Poland. These areas are characterized by a poor socio-economic situation not only in comparison to the rest of Poland but also to the EU and by a large outflow of inhabitants.

To achieve the assumed goals, the following hypotheses were formulated:

H1.

Higher earnings abroad are a factor increasing the propensity to migrate among surveyed nursing students and graduates living in rural areas.

H2.

The willingness to gain professional experience is a factor encouraging people to leave the country.

H3.

The willingness to earn money for an apartment/house is a factor pushing respondents to emigrate.

H4.

The respondents’ previous migration experience is a factor encouraging them to make migration decisions in the study group.

To select a research sample, the focus was on nursing students studying in five voivodeships of Eastern Poland: Warmia-Masuria, Podlaskie, Lublelskie, Świętokrzyskie, and Podkarpackie. The main purpose of selecting the sample was to select the most important centers in the surveyed voivodeships. One of the criteria was that the research would be conducted only in the field of nursing in public schools (universities and medical universities) where education is free of charge (full-time studies) and in those universities that have two levels of education (master’s and bachelor’s degrees) and accreditation from the Ministry of Health. Such a sample guarantees that the surveyed students will have similar, high-quality qualifications; therefore, they will have similar job opportunities, and the level of education obtained at these universities will be comparable. In the case of full-time studies at public universities, the costs of education are borne by the state. Therefore, the emigration of highly qualified people after graduation is a loss for Poland in the form of temporarily or permanently lost labor resources.

The research sample was a random sample among nursing students from rural areas and studying at the following universities: Medical University of Lublin (Lublin Voivodeship), University of Rzeszów (Podkarpackie Voivodeship), Medical University of Białystok (Podlaskie Voivodeship), Jan Kochanowski University in Kielce (Voivodeship Świętokrzyskie), and the University of Warmia and Mazury in Olsztyn (Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship).

The research tool was an original questionnaire created for the needs of a broader study (34 questions). The decision to conduct a direct survey was related to the desire to obtain the highest possible return on correctly completed surveys. The personal participation of the authors in the study allowed them to present tips, explain concepts, and respond to possible doubts of the respondents. Additionally, after completing the study, discussions took place in the form of an additional direct interview. The respondents presented their problems and described their family and financial situations, future professional plans, and migration plans. Everyone present in the classes took part in the study (the study was conducted in all semesters/years, so it covered the entire population). The research was conducted first during compulsory classes, i.e., exercises or laboratories, and then during lectures. In order to include absent people in the study, blank questionnaires were left for them at the lecturers’ disposal. In this way, we managed to obtain over 150 additional completed questionnaires, which were sent or collected personally by the authors.

The research was conducted in five nursing education centers (from May to November 2018). Approximately 1% of surveys were eliminated (due to most key questions not being answered). Thus, 745 surveys qualified for calculations. The number of respondents was greater than the minimum sample size, taking into account all levels of maximum estimation error. This result represents over 34% of the population. However, for the purposes of the article, a group of respondents living in rural areas was selected. The obtained sample consisted of 378 respondents and was larger than the minimum sample size determined for the known and finite population of nursing students at the selected universities, with an assumed permissible estimation error of 5 percent.

The survey intended to help assess the conditions that may contribute to young people making a migration decision. It consisted of two parts. The first part of the survey concerned the actual survey questionnaire, in which 4 aspects can be distinguished:

- Findings regarding satisfaction with the chosen field of study, chances of finding a job, and the purpose of migration;

- Identification of push–pull factors (push and pull for migration);

- Determining the tendency to migrate;

- Determining the migration experience of the surveyed students over the last 5 years.

The second part of the survey—the personal details—allowed for collecting basic data about the respondents, such as education, employment, marital status, having children, apartment/house, income level, number of people in the household, and place of residence.

In order to verify the first hypothesis (H1: Higher wages abroad are a factor that increases the propensity to migrate among surveyed nursing students and graduates living in rural areas), respondents were asked the following question: ‘Which factors encourage you to migrate and which are the most important to you?’. Respondents were asked to indicate whether ‘higher wages’ were an important or unimportant factor for them. This question was included in the model.

For the second hypothesis (H2: The willingness to gain work experience is an incentive to leave the country), the following question was asked: “What factors encourage you to leave the country and which ones are most important to you?”. Respondents were asked to indicate whether ‘gaining work experience’ was an important or unimportant factor for them. This question was included in the model.

Two survey questions were used to verify the third hypothesis (H3: The desire to earn money for an apartment/home is a factor encouraging respondents to emigrate):

- -

- “Do you plan to buy your own apartment/home in the future?” (after returning to Poland). Possible answers: 1—no, I do not; 2—yes, I plan to buy an apartment/home. This question was included in the model.

- -

- “What would be the purpose of the migration (you can mark more than 1 answer)?”. Respondents had the following options to choose from: to get a job; to continue their education; to have a family reunion; other (respondents could write their main purpose in this question). If someone wrote ‘buying an apartment/home’ in the last option, this was additional confirmation of H3.

In order to verify the fourth hypothesis (H4: The respondents’ previous migration experience is a factor encouraging them to make migration decisions in the study group), the following question was asked to the surveyed students: “Have you been abroad (gainfully employed) in the last 5 years?”. Possible answers: 1—yes; 2—no. This question was included in the model.

Due to the fact that the basic research variable was the tendency to migrate, and was therefore a qualitative variable, the research method was logistic regression analysis for a dichotomous variable. The logistic regression model for the tendency to migrate can be expressed by the following equation [85]:

where denotes a dichotomous variable equal to 1 when the respondent is characterized by a high tendency to migrate and 0 when the respondent is characterized by a low tendency to migrate; denote independent variables; and are regression coefficients. The logistic function assumes values between 0 and 1. The dependent variable (tendency to migrate) and the independent variables (factors influencing migration) are qualitative in the study.

The logistic regression model is a special case of the generalized linear model. Most often, a monotonic function is used to model phenomena. Usually, the values of the explained variable indicate the occurrence or non-occurrence of a certain event that we want to forecast. Logistic regression then allows us to calculate the probability of the occurrence or non-occurrence of the event we are forecasting (the so-called probability of success). For a logistic regression model, it is required that the observations be independent of each other, and the logit transformation is linearly dependent on the explanatory variables. The appropriate selection of independent variables affects the correctness and accuracy of inferences in this model. Therefore, it should include only variables that have a significant impact on the variable . None of them can be omitted so as not to reduce the quality of the analysis. The number of observations included in the analysis is also important. It cannot be too small so as not to reduce the quality of the analysis. Therefore, the backward stepwise regression procedure was used to estimate the model. In the first step, a model containing all potential explanatory variables is constructed, and then, in subsequent steps, those variables whose impact on the dependent variable is the least significant are eliminated. The gradual elimination of variables continues until a model with as many relevant parameters as possible is obtained.

Statistica (the Statistica 13.3 PL statistical package) and Excel software (Office 365 A1 Plus for faculty, version 2404) were used to analyze the quantitative data.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Group (Respondent Profile)

The basis for the analysis of the empirical research was a research sample of students at state universities (nursing) with first- and second-cycle studies. Nursing is a highly feminized profession. Overall, 79% of the sample was women and 21% was men. The average age was 24 years. Most respondents did not have children (87%) or a spouse (79%).

The results also show that 74% of students combined study with work (first-cycle study graduates, part-time students, people improving their qualifications), of which 21% worked in more than two jobs. In the case of 89% of respondents, the desired form of employment was an employment contract. Additionally, 81% of respondents were satisfied with their field of study, and 92% of respondents believed that they would have no problems finding a job after graduation. Over 57% of respondents had migration experience in the last 5 years preceding the research.

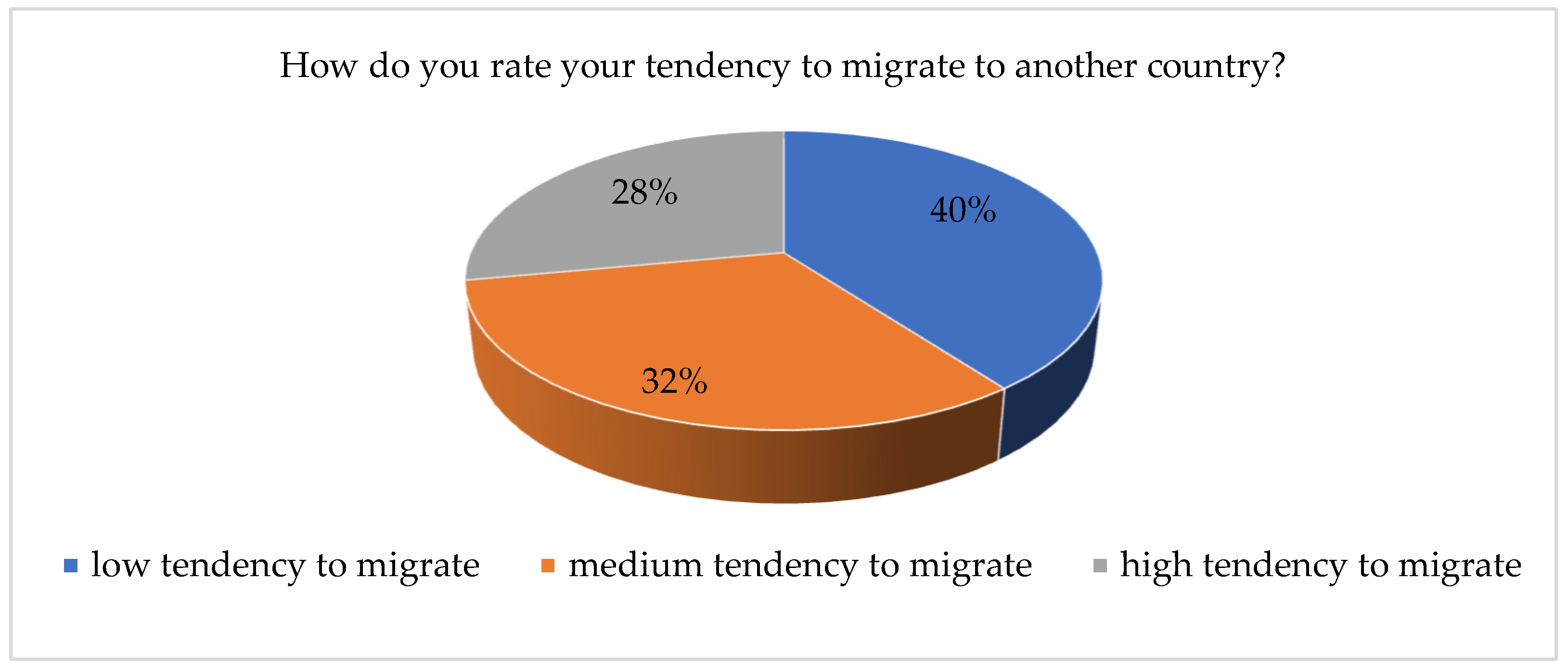

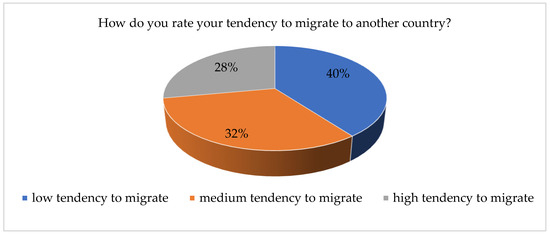

The graphic analysis results of our research show that 28% of respondents described their tendency to migrate as high, and 32% described it as average (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The tendency to migrate of respondents living in rural areas.

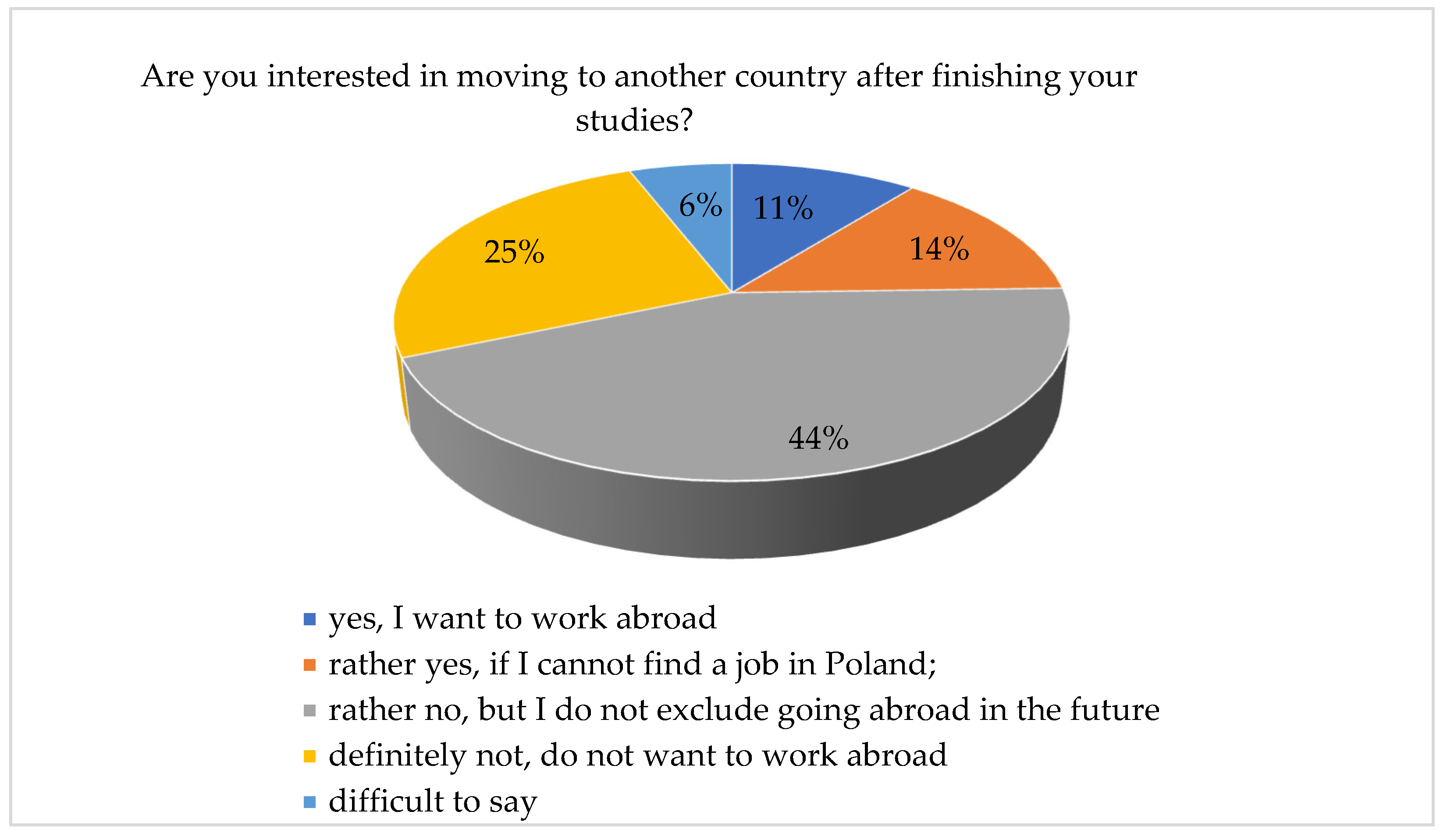

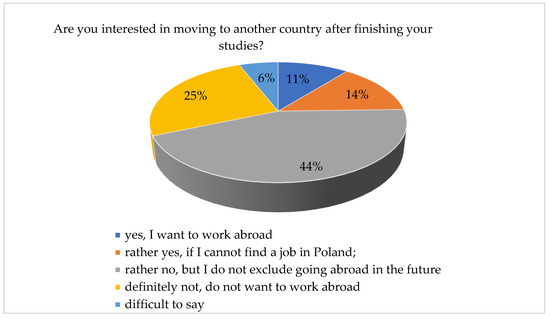

The tendency to migrate is a subjective assessment of one’s mobility. Therefore, it is important to supplement this information with data regarding the declared willingness to emigrate after graduation (Figure 2). The results show that 11% of respondents wanted to emigrate immediately after completing their studies, and 14% would if they did not find a job in Poland. A further 44% did not rule out going abroad in the future, while 25% of the surveyed people declared their willingness to stay in the country.

Figure 2.

Willingness to move to another country after graduation.

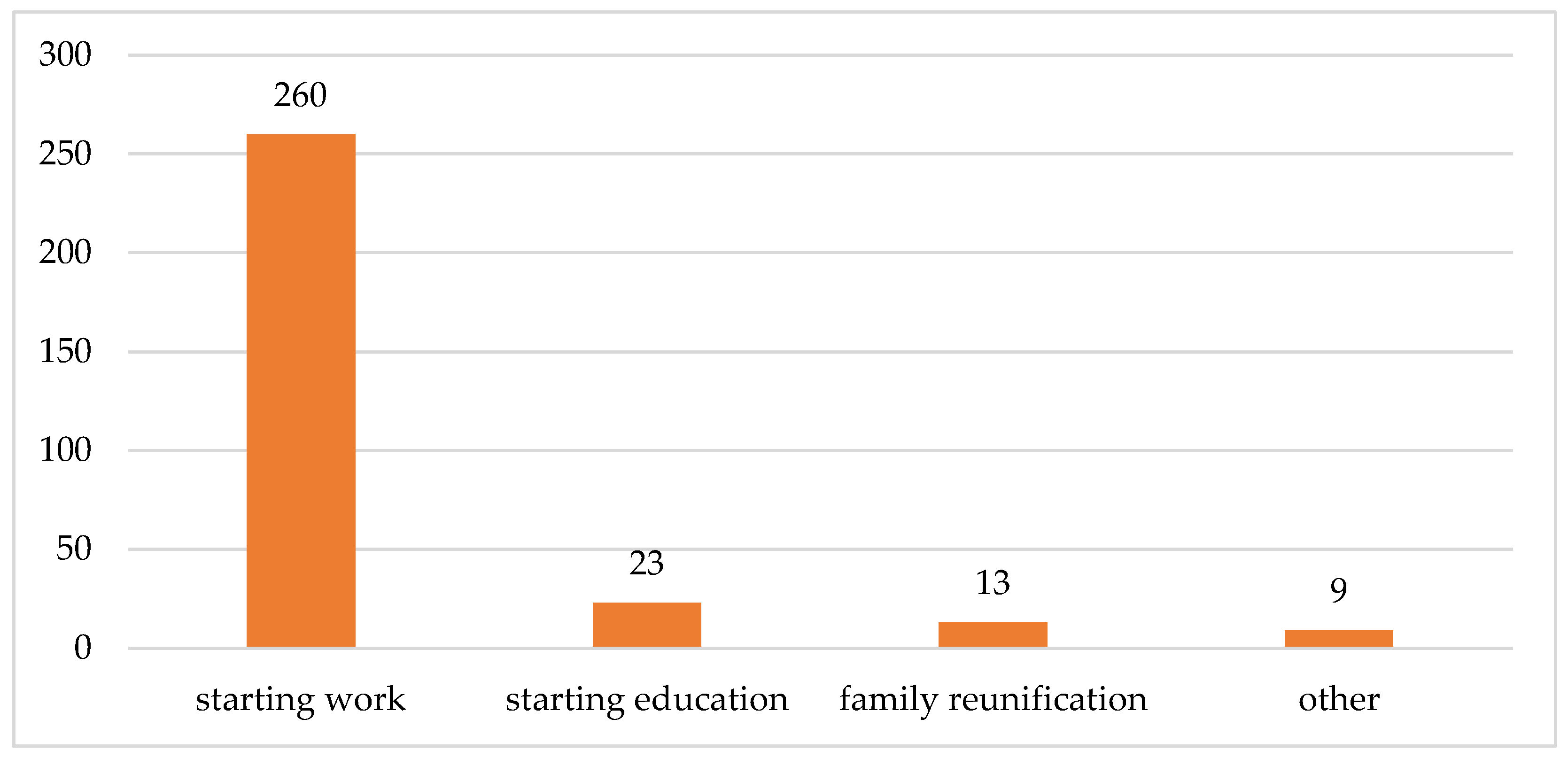

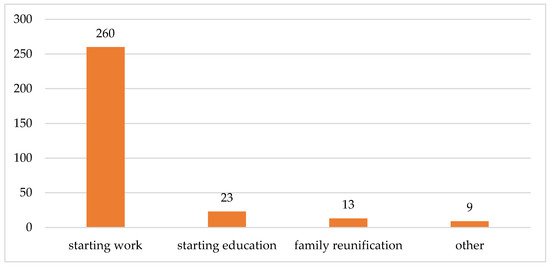

The above question was supplemented by the respondents’ indication of their purpose of migration. Not all surveyed nursing students answered this question. The results in Figure 3 show the purpose of emigration indicated by the respondents.

Figure 3.

The purpose of emigration.

For this question, respondents were allowed to choose more than one answer. Therefore, some of them marked two. Most often (260 responses), the purpose of the trip was to work, followed by studying (23 responses) and family reunification (13 responses). People who marked two answers most often marked two options: “taking up a job” and “taking/continuing education”. People who declared other reasons as their goal (nine answers) mentioned earning money for an apartment/house, a car, a wedding, and further education.

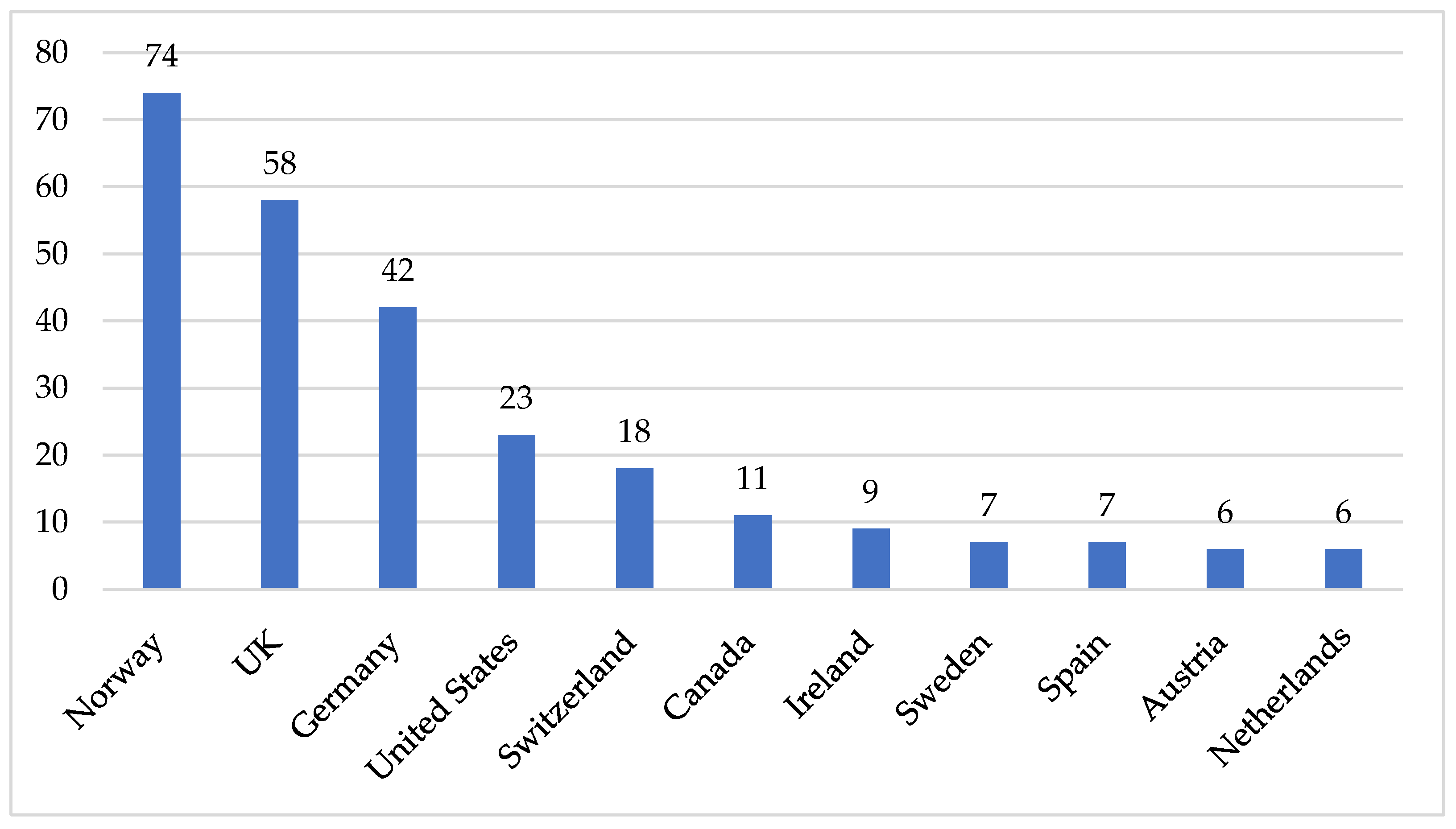

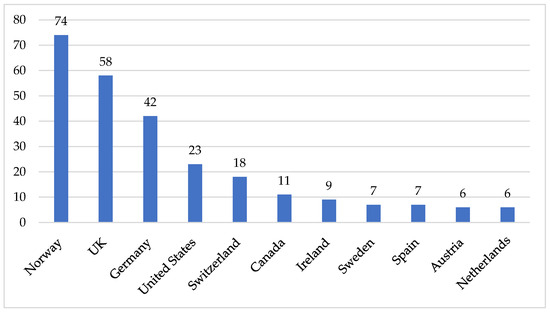

The survey also yielded 286 responses which indicated the countries to which the surveyed students would like to emigrate after completing their studies. It was possible to provide more than one answer. Not all respondents answered this question.

Figure 4 is a graphic visualization of the main directions of economic migration. The most frequently mentioned destinations were rich European countries, i.e., Norway, Great Britain, and Germany. Among the non-European countries, the most frequently chosen countries were the USA and Canada.

Figure 4.

Main directions of emigration.

3.2. Potential Pull and Push Factors for Nursing Students from Rural Areas of Eastern Poland

Determining the causes of migration is important from a social and economic point of view. According to the push–pull theory [48], factors were grouped into push, pull, and intermediate obstacles.

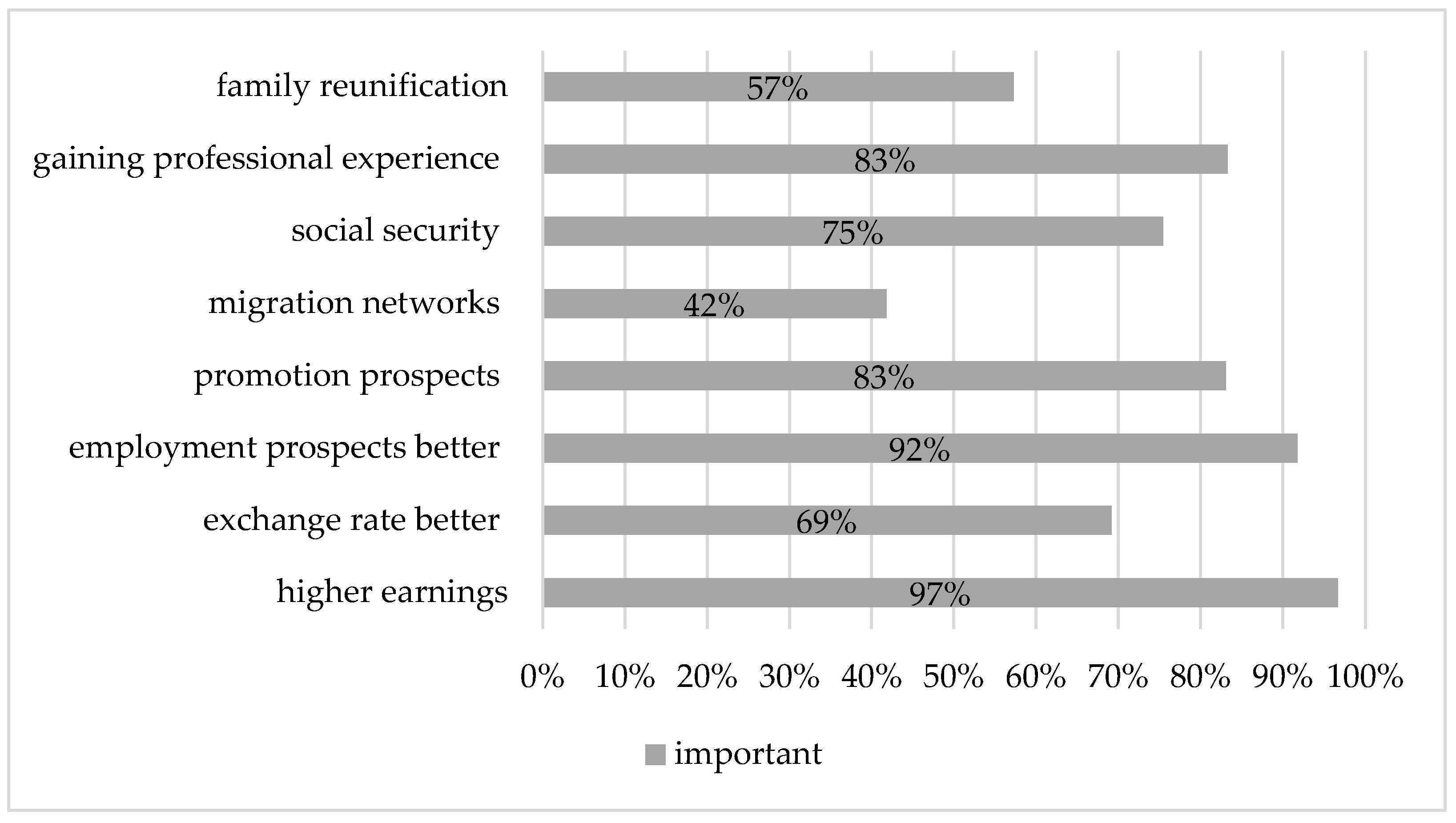

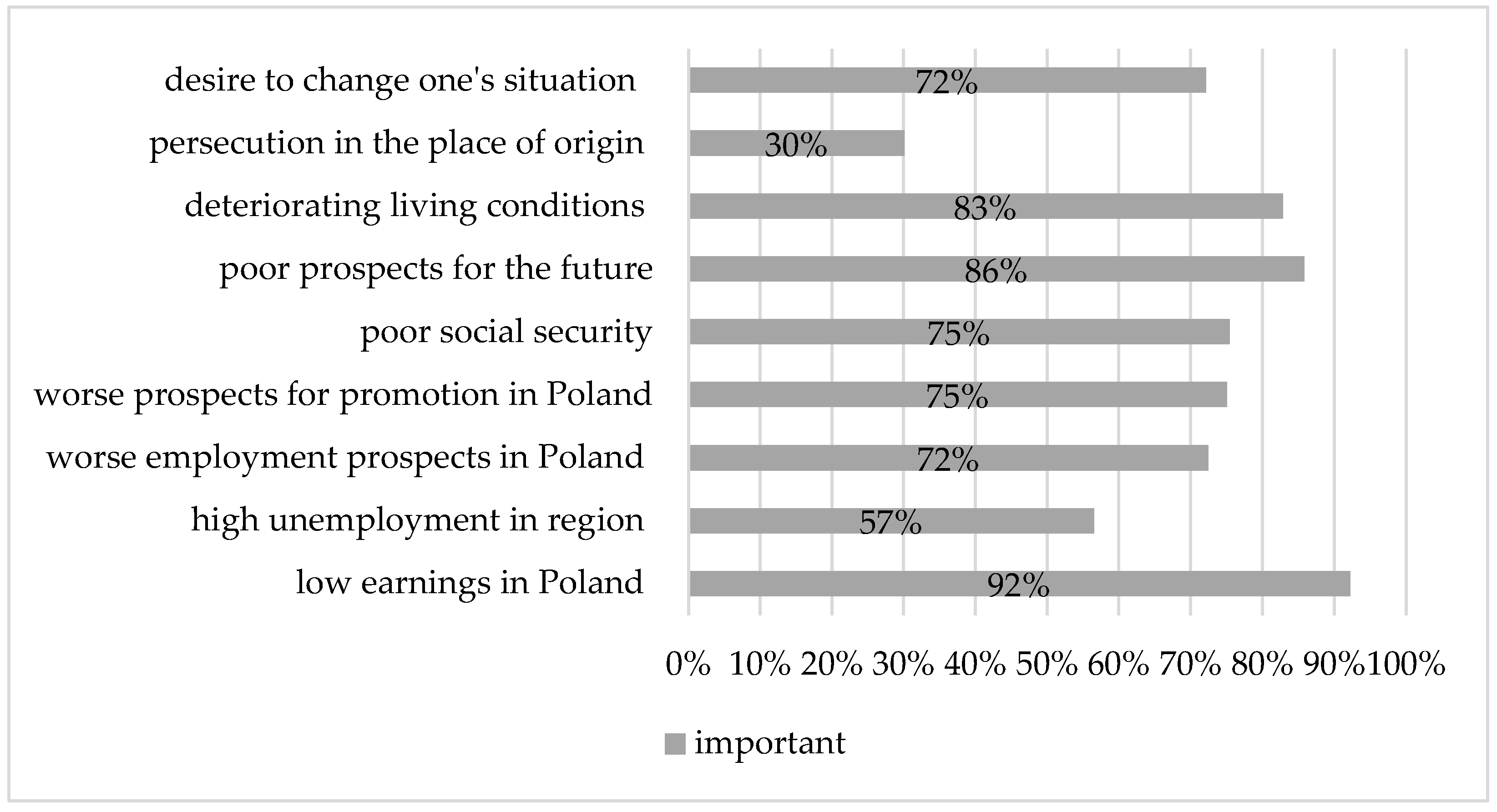

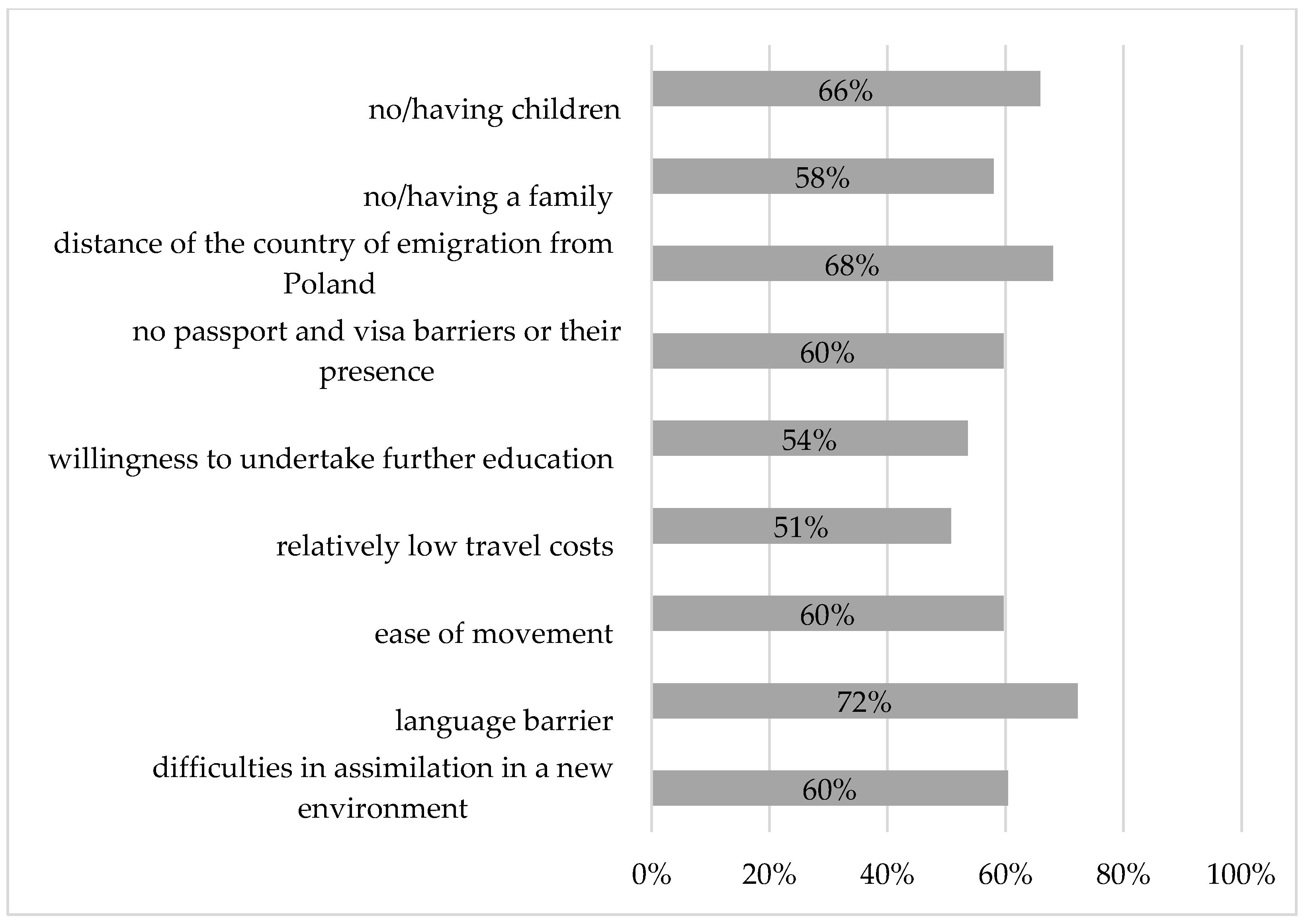

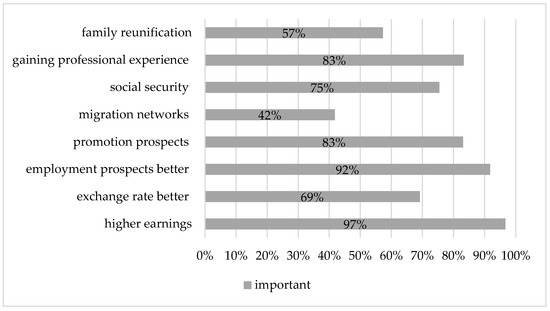

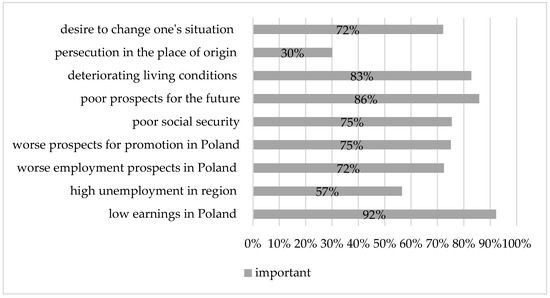

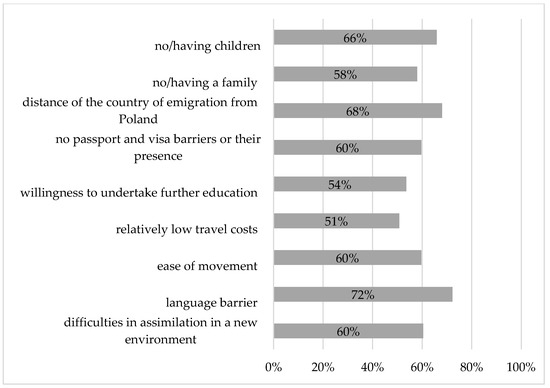

First, the pull factors were analyzed (Figure 5), followed by the push factors (Figure 6) and other factors (Figure 7).

Figure 5.

Pull factors.

Figure 6.

Push factors.

Figure 7.

Other factors.

The results presented graphically in Figure 5 show that the factors attracting people to migrate abroad most frequently indicated by the respondents were higher earnings abroad (97%), better employment prospects (92%), gaining professional experience (83%), and the prospect of promotion abroad (83%).

On analyzing the research results, it was observed that among the push factors, respondents most often indicated economic factors. They indicate (Figure 6) that the most crucial factor pushing people to migrate is low wages in Poland (92%), followed by poor prospects for the future (86%) and deteriorating living conditions (83%).

Figure 7 shows that the most important factor for respondents was the language barrier (mentioned by 72% of respondents). Other important factors included the distance of the country of emigration from Poland (indicated by 68% of the respondents) and having children (66%), as well as the ease of movement, no need for passports and visas, and difficulties in assimilation in an unfamiliar environment (60% each).

3.3. Model of Tendency to Migrate among Nursing Students from Rural Areas of Eastern Poland

In this section, a binomial logistic regression model is estimated following the specification described in Equation (1), where the dependent variable is the dichotomous variable propensity to migrate. In linear regression, whether the association of explanatory variables with the dependent variable is significant is determined using a joint hypothesis with a test based on the Fisher distribution. Due to the fact that errors in logistic regression have a binomial distribution, a chi-square distribution with a likelihood ratio test is used.

Based on the questions included in the survey and the above analyses (Section 3.2), a set of factors was developed including the potential causes of migration of people living in rural areas who already perform or want to pursue the profession of nurse. The summary is presented in Table 1. The explanatory variables, in addition to pull and push factors, included several general variables such as the respondent’s gender, education, employment, and marital status.

Table 1.

Potential pull and push factors for nursing students from rural areas of eastern Poland.

Estimating the model will allow for the verification of the hypotheses and for identifying other potential determinants of nursing students’ migration intentions. Moreover, the most frequently used measure of association, namely the odds ratio, was included in the model estimates. This makes it possible to compare the chance of having a high tendency to migrate in a group exposed to a given factor with the chance of this condition occurring in a group not exposed to it. The estimates of the final version of the model with only significant parameters are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Results of estimating a binomial logistic regression model of determinants that encourage nursing students from rural areas to leave Poland to work abroad.

The most important factor, from the point of view of the odds ratio, prompting the surveyed nursing students to leave the country was the desire to change their poor prospects for the future. This factor, when considered important, increases the chance of having a high propensity to migrate by more than twenty-six times than if this factor is considered unimportant. The high rank of this factor may be because it focuses on many aspirations of young people to achieve their goals, such as their material, professional, and family development.

The next factor increasing the tendency to migrate was gaining professional experience. It increases the chance of being highly prone to migration more than fivefold compared to people for whom this factor is not important. The significance of this factor positively verifies the hypothesis H2.

The identification of another statistically significant factor in the form of plans to purchase one’s apartment or house justifies the research hypothesis H3. Recognizing this factor as important increases the probability that a given person will have a high tendency to migrate by more than three times compared to people for whom such a factor is considered unimportant. The importance of this variable results indirectly from the need to obtain adequate capital to purchase one’s apartment and develop a family.

The last two factors are closely related to the innate desire to change one’s place of residence. An interesting result was obtained in the case of young nurses who had been abroad in the last 5 years. This factor almost doubled the chance of being in the group of people with a higher tendency to migrate than in the case of people who have not been abroad in the last 5 years. The obtained result therefore positively verifies hypothesis H4.

The important variables influencing the propensity to migrate include three negating factors, which reduce the chance that a person emphasizing a given factor as important will have a high propensity to migrate. One of them is the distance from the country of origin, which may be explained by barriers to communication and longing for family. The remaining two negating factors can be treated as one factor, determining difficulties in assimilation in a new place of migration and the related possibility of persecution. These variables are significantly related to ensuring security in the country of migration.

In the case of the presented model, it was assessed in the context of fit to the data. For this purpose, the Hosmer–Lemeshow test statistic was determined, verifying the null hypothesis that there is no significant difference between the observed and predicted values of the dependent variable. The result of the above test indicates that the model fits the data well.

4. Discussion

Historical conditions in Poland are responsible for the fact that rural areas located in the central and eastern parts of the country are less developed than others. Their characteristic feature is, among other things, a very high share of agriculture in the economic structure of the villages. The poorly developed local non-agricultural labor market has caused the migration of young people, which has resulted in an unfavorable demographic structure in these areas (high share of the elderly population, imbalance in gender proportions among the population aged 20–34, drainage of entrepreneurs and educated people from rural areas, etc.) and, in extreme cases, depopulation phenomena [5,86].

The process of population outflow intensified in Poland after 2004 when it joined the EU. At that time, large regional differences in population outflow were recorded, and a double-digit percentage of emigration of young people, many aged 18–44, occurred in several Polish voivodeships. These included, among others, the Podlaskie Voivodeship (13%) and Podkarpackie Voivodeship (almost 12%) in Eastern Poland as well as the Opole Voivodeship (15%) [87,88]. The analysis of subsequent data from the 2021 National Census regarding the number of emigrants per 1000 inhabitants divided by voivodeship showed that the largest temporary foreign migrations took place, among others, in the Podkarpackie, Podlaskie, and Warmian-Masurian Voivodeships, i.e., those covering Eastern Poland [89].

Determining the causes of migration of young people living in rural areas of Eastern Poland is important from a social and economic point of view, especially if they belong to a professional group in which there is a shortage of workers in the national and local labor markets. Thanks to the knowledge of the factors encouraging migration, it is possible to establish an effective plan to prevent young and educated people from leaving rural areas.

The push–pull theory is often used in the migration research literature, for example, in the analysis of students’ decisions to study abroad [90]. For this purpose, as a rule, a number of pull and push factors are adopted at various levels of integration of individuals, i.e., at the individual, community, and regional/national levels.

The push–pull theory was also used in our research. These factors were determined and subjectively assessed by respondents, namely nursing students from Eastern Poland, living in rural areas. They can be divided into economic, professional, personal, and other factors. The respondents indicated that when making decisions about emigration, economic factors are the most important for them in terms of both push factors, including the low level of wages in Poland (92% of respondents) and deteriorating living conditions (83%), and pull factors, including the high level of wages abroad (97% of respondents). The low wages in Poland result in a low quality of life, and emigration abroad is an opportunity to change one’s financial situation. Pawlonka [1] also points to the importance of improving the quality of life as a factor influencing the sustainable development of rural areas. We found that certain professional factors were also very important, which turned out to be pull factors: better employment prospects (92%), promotion abroad (83%), and gaining professional experience (83%). Among the other factors, poor prospects for the future (96%) also turned out to be an important push factor for migration for them.

Research also shows that, apart from economic factors, non-economic variables also shape the migration decisions of nursing students. Having a family (children/spouses) should be taken into account. Other related factors in this context are the distance from the country of origin and travel costs for quick contact with family, which was confirmed by the presented research results. The most important factors related to family were the distance of the country of emigration from Poland and having children. Papadopoulos and Fratsea [56] also drew attention to the existence of several interacting factors, especially non-economic ones. Workers pay attention to an important aspect when making migration decisions—achieving a balance between professional life (and self-fulfillment) and family life.

Other non-economic factors affecting the tendency to migrate are related to language knowledge. This would allow potential migrants to integrate with the local and professional environments. The research results confirmed that, for the respondents, the most important of the remaining factors analyzed was the language barrier (indicated by 72% of respondents). This seems understandable if we consider the essence of nurses’ work. Good knowledge of the local language, not only industry-specific, is necessary to perform your duties well and communicate with patients and their families.

A literature review of the phenomenon of emigration of people with higher qualifications (including nurses), through the prism of push–pull factors, allowed us to notice that the most important factor pushing people out of the country is low wages. At the same time, the higher level of wages in the country of destination is an attractive factor in obtaining a higher income from work. For educated people with specialized qualifications and skills, apart from financial benefits, non-economic factors are often equally important. Such additional factors attracting people to go to a specific country may be the possibility of further education, learning a foreign language, the possibility of conducting scientific research, learning about new technologies, better working conditions, career development, or easier regulations and procedures for starting one’s own business. However, the most important condition, from an institutional point of view, facilitating the migration of specialists is a favorable migration policy. It is usually strongly focused on attracting high-class professionals [91], which is also emphasized by Pawlonka [1].

Based on the research and literature review, it was possible to verify the hypotheses and achieve the research goals.

The first hypothesis, assuming that higher earnings abroad are a factor increasing the tendency to migrate, was not positively verified. It turns out that for 97% of the surveyed nursing students living in rural areas, higher earnings abroad were an important factor in making migration decisions. However, the tendency to migrate model (taking into account 21 different factors) showed that this factor (high earnings abroad) in connection with the tendency to migrate declared by the respondents is not statistically significant. Although this factor turned out to be directly insignificant, the significance of the low level of wages in the country of origin is probably reflected indirectly in such important factors as plans to buy a new apartment (H3) or improve prospects. As other studies have shown, the reasons for migration of the young generation are different, providing a chance for a better life. This applies especially to the economic migration of young people from peripheral areas [50,51,52,53,54,55] and people with specific qualifications and skills sought on the domestic and foreign markets.

The second hypothesis (H2), assuming that the desire to gain professional experience is a factor encouraging people to leave the country, was positively verified. Our research shows that the factor increasing the tendency to migrate was gaining professional experience. Expanding professional experience in institutions outside the country of residence increases the possibility of higher earnings and obtaining the necessary recommendations for work in the profession.

The third hypothesis (H3), assuming that the desire to earn money for an apartment/house is a factor pushing respondents to emigrate, was positively verified. The research shows that the surveyed people would emigrate for work purposes (260 people) to save, among others, for an apartment or house. The model estimates show that this is a statistically significant goal. The importance of this variable results indirectly from the need to obtain adequate capital to purchase one’s own apartment and develop a family.

Additionally, the last hypothesis (H4), assuming that the respondents’ previous migration experience is a factor encouraging them to leave, was positively verified. The factor “having migration experience in the last 5 years” in the case of young nurses almost doubled the chance of being in the group of people with a high tendency to migrate than in the case of people who have not been abroad in the last 5 years. Most likely, previous migration experience allows people to create networks of acquaintances and connections, i.e., migration networks, which would make it easier for them to plan their next departure from the country. However, this would need to be confirmed. This could be the goal of another study conducted among this group of respondents.

The estimates of the tendency to migrate model presented in this work indicated eight statistically significant determinants influencing the tendency to migrate, which increased or decreased the probability that a given person would be in the group with a high tendency to migrate. Among the factors, we could distinguish planning to buy one’s own apartment or house in the future, the desire to gain professional experience, migration experience (in the last 5 years), poor prospects for the future, and ease of movement. The negating factors turned out to be difficulties in assimilation in the new environment in the place of migration and the related potential for persecution in the place of origin as well as the distance from the country of origin.

The most important factor in the above model that would prompt the surveyed nursing students to leave the country was the desire to change their poor prospects for the future. The high rank of this factor may be due to the fact that it focuses on many aspirations of young people to achieve their goals, such as their material, professional, and family development. Another factor increasing the tendency to migrate was gaining professional experience and purchasing one’s apartment or house. The last two factors are closely related to the innate desire to change one’s place of residence. An interesting result was obtained in the case of young nurses who had been abroad in the last 5 years. This is important because, as research by others shows, emigrants also take into account their experiences with integration in the local labor market, especially in rural areas [31].

The important variables influencing the tendency to migrate include three negating factors, which reduce the chance that a person emphasizing a given factor as important will have a high tendency to migrate. One of them is the distance from the country of origin, which may be explained by barriers to communication and longing for family. The remaining two negating factors can be treated as one factor, determining difficulties in assimilation in a new place of migration and the related possibility of persecution. These variables are significantly related to ensuring security in the country of migration.

The surveyed students from the main centers of Eastern Poland, studying nursing and living in rural areas, were satisfied with the chosen field of study (81%) and were aware that they were not at risk of unemployment and would have no problems finding a job in Poland (92%). Despite this, they did not reject the idea of emigration. The greater mobility of people from rural areas was also confirmed by [2,3]. The most frequently indicated emigration countries were rich European countries, i.e., Norway, Great Britain, and Germany. Among the non-European countries, the most frequently chosen countries were the USA and Canada. All these countries are characterized by a high GDP per capita, low unemployment rates, and a demand for nurses.

As many as 60% of the respondents described their tendency to migrate as high or medium (28% high; 38% medium). The respondents in the study declared their willingness to go abroad after completing their studies. It seems that 11% of people willing to emigrate do not constitute a very large number of people planning to leave the country. However, if we take into account those who planned to leave if they do not find a job (14%), as well as respondents who did not exclude it in the future (44%) and those who have not yet made a final decision (6%), this percentage increases up to 75%. This already indicates the huge scale of the problem. It turns out that 3/4 of young nurses living in rural areas may go abroad in the future from Eastern Poland. Of course, these are not yet implemented migration decisions, but only plans. However, this does not change the fact that they indicate the problem of a potential outflow of nursing staff from regions that are already socio-economically weak [92]. This may cause not only demographic effects (depopulation of areas with a strong outflow) but also a change in the demographic structure, not only through the outflow of young and educated people but also due to the already aging nursing staff (the average age of Polish nurses is 52 years) [93]. This, in turn, will reduce the already low competitiveness of the region and cause further deepening shortages in the nursing labor market. Additionally, despite the costs incurred for educating nurses (full-time studies are free of charge in Poland), it is not the regions where they would live and work who will receive the benefits but the regions (countries) of their target emigration.

Economic trips, which dominated in the surveyed group (260 people indicated their willingness to work), are a direct benefit for migrants and their families (and indirectly also for the region). They allow people to earn money to buy an apartment or use the earned funds to start a business. Additionally, thanks to such trips, emigrants gain new skills and learn new techniques and work methods. The surveyed nursing students from Eastern Poland are hard-working and ambitious people who want to expand their knowledge and improve their professional qualifications. The research shows that almost 74% of the surveyed students worked as a nurse and studied at the same time, of which 21% worked in more than two places of work. This may indicate that the salary from one job is insufficient to support oneself and one’s family. A much higher level of wages in the learned profession is a factor encouraging people to go abroad for work (as indicated by 97% of respondents). Therefore, economic emigration offers, for them, a chance for professional development and an opportunity to achieve financial stability. The benefits of migration also include transfers of funds to the bank accounts of emigrants and their families, which leads to an increase in consumption and has a positive impact on the economic development of the region.

Economic emigration is favored by the existence of a sufficiently large wage gap between the host country and the migrant’s country of origin, which is often emphasized by specialists in the field of economic sciences [19]. For example, the remuneration of nurses working in hospitals is (in USD/year) 19,619 in Poland, and in countries that are the most popular destinations for emigration as indicated by nursing students from the researched academic centers, it is as follows: 47,736 in Great Britain, 55,303 in Germany, 60,436 in Ireland, 65,889 in the Netherlands, 70,985 in Norway, and 76,053 in Switzerland [94].

After obtaining a diploma, the Polish and European labor markets open up to these people, and thus, their mobility and tendency to migrate increase. After completing their studies, the surveyed nursing students may take up work abroad, becoming economic migrants due to the differences in wage levels in Poland and other European and non-European countries. Their departure does not only mean the loss of healthcare specialists needed by society. Additionally, emigration deepens the shortage of nurses in the domestic labor market, making the market unsustainable. Moreover, it is also a loss for the country resulting from financing the education of people (full-time studies) whose skills and qualifications are used by other countries. Another aspect that may affect sustainable development in the context of healthcare is the aging of the nursing population, the decreasing number of young people entering the profession, and the relatively high percentage of those deciding to leave for work. It should be emphasized that all young nurses in Poland have completed their studies. Higher education for nurses is a requirement that had to be met after Poland joined the European Union.

There are several push factors and pull factors that potentially support the decision to migrate [95]. Polish nurses indicated that the most important push factors were [57,95] unfavorable pay and work conditions, heavy workload, too few rights at the workplace, and lack of opportunities for personal development.

These are factors that influence the level of job satisfaction [96]. However, when it comes to attracting factors, Polish nurses paid attention to the ease of finding a job abroad resulting from staff shortages among medical staff and the related demand for foreign work, better working conditions, a better social welfare system, and a well-developed migration network [59,97].

The most important push and pull factors were pay and working conditions [98]. Moreover, Polish nurses see going to work abroad as an opportunity to gain new experiences and gain greater self-confidence [98]. Therefore, in order to retain nurses in the country, it would be necessary to take actions that, in addition to increasing the level of wages, would allow them to be attached to the workplace, including by providing them with opportunities for personal development and education and increasing their rights [95]. It seems important to create a long-term program for planning human resources in order to achieve stabilization and ensure the appropriate number of nurses [99]. Thus, the results for both people planning to emigrate and those who have returned are similar.

Despite the benefits of migration not only for migrating people but also for outflow areas, it is necessary to consider how to change the attitude of young people studying nursing and influence their plans. This is important because when analyzing the nursing labor market, it can be noticed that the foreign emigration of educated and ambitious young nurses not only has a negative impact on the demographic structure of the outflow area (voivodeship) but also deepens the shortage of specialists in the local labor market. The lack of people with appropriate education and skills in the field of medical services results in a decrease in the region’s competitiveness.

In the face of the phenomenon of migration from rural areas, strategies should be developed to counteract the depopulation of rural areas. Setting the goal of sustainable development of rural areas should strengthen these areas in terms of the appropriate level of healthcare or education, economic appreciation of the nursing profession, improvement of infrastructure, and the possibility of diversification of new industries [4]. National, regional, and EU funds seem to be essential in creating or maintaining the sustainable development of rural areas.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.K. and L.M.; methodology, G.K. and L.M.; software, G.K. and L.M.; validation, G.K. and L.M.; formal analysis, G.K. and L.M.; investigation, G.K. and L.M.; resources, G.K. and L.M.; data curation, G.K. and L.M.; writing—original draft preparation, G.K. and L.M.; writing—review and editing, G.K. and L.M.; visualization, G.K. and L.M.; supervision, G.K. and L.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available in order to protect the privacy of the interview partners. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Pawlonka, C. Społeczne aspekty zrównoważonego rozwoju. Rynek Społeczeństwo Kult. 2018, 4, 28–31. [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos, A.G.; Fratsea, L.-M.; Karanikolas, P.; Zografakis, S. Reassembling the Rural: Socio-Economic Dynamics, Inequalities and Resilience in Crisis-Stricken Rural Greece. Sociol. Rural. 2019, 59, 474–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Report of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development. Diagnosis of the Socio-Economic Situation of Agriculture, Rural Areas and Fishing in Poland, Warsaw. 2019. Available online: https://www.google.pl/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwjX-7uF2PuGAxWIQ_EDHXHvDnkQFnoECBAQAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.gov.pl%2Fweb%2Frolnictwo%2Fd (accessed on 7 April 2024).

- Papadopoulos, A.G.; Baltas, P. Rural Depopulation in Greece: Trends, Processes, and Interpretations. Geographies 2024, 4, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wpływ Polityki Spójności na Rozwój Obszarów Wiejskich, Raport Końcowy 2019, IRWIR PAN Wolański. Available online: https://www.irwirpan.waw.pl/714/nauka/wplyw-polityki-spojnosci-na-rozwoj-obszarow-wiejskich (accessed on 7 April 2024).

- Bera, R. Wielka Emigracja Zarobkowa Młodzieży; UMCS: Lublin, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Grabowska, I. The Transition from Education to Employment Aboard: The Experiences of Young People from Poland. Eur.-Asia Stud. 2016, 68, 1421–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szyszka, M. Zagraniczna migracja zarobkowa jedną ze strategii życiowych młode go pokolenia. Rocz. Nauk. Społecznych 2016, 8, 143–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sarnowska, J. Double Transition: University-to-Work Abroad and Adulthood. Rocz. Lubus. 2016, 42, 215–228. [Google Scholar]

- Mirkowska, P.P. Drogi Społeczno-Zawodowe Młodych Kobiet Migrujących z Małych Miejscowości do Warszawy; Youth Working Papers; University of Warsaw, Centre of Migration Research (CMR): Warsaw, Poland, 2018; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Hałaj, J.; Stec, M. Zagraniczne Migracje Zarobkowe Polskiej Młodzieży w Opinii Studentów z Województwa Podkarpackiego—Perspektywa Psychologiczno-Ekonomiczna; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Rzeszowskiego: Rzeszów, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Biernacka, M. Postawy Migracyjne Młodzieży Akademickiej Białegostoku, [w:] Edukacja w Czasie Zmiany. Kontekst Pogranicza, A. Zawistowska (red.). Pogranicze. Studia Społeczne. 2017. Available online: https://repozytorium.uwb.edu.pl/jspui/bitstream/11320/5966/1/Pogranicze_31_2017_M_Biernacka_Postawy_migracyjne_mlodziezy_akademickiej_Bialegostoku.pdf (accessed on 7 April 2024).

- Szczebiot-Knoblauch, L.; Kisiel, R. Skłonność do Emigracji Zarobkowej Studentów Uniwersytetu Warmińsko-Mazurskiego; Uniwersytet Warmińsko-Mazurski w Olsztynie: Olsztyn, Poland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jończy, R. Exodus zarobkowy opolskiej młodzieży. Polityka Społeczna 2006, 10, 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Krasnodębska, A. Preferencje Zawodowe Opolskich Studentów a Kwestia Zagranicznych Migracji Zarobkowych; Wydawnictwo Instytut Śląski: Opole, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Jończy, R.; Rokita-Poskart, D.; Tanas, M. Exodus Absolwentów Szkół Średnich Województwa Opolskiego do Dużych Ośrodków Regionalnych Kraju Oraz za Granicę (w Kontekście Problemu Depopulacji Województwa Oraz Wyzwań dla Szkolnictwa Wyższego i Regionalnego Rynku Pracy); Wydawnictwo Instytut Śląski: Opole, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Grabowska, M.; Jończy, R. (Eds.) Edukacyjny, Zarobkowy i Definitywny Exodus Młodzieży z Obszarów Peryferyjnych Dolnego Śląska i Jego Skutki dla Zrównoważonego Rozwoju Regionalnego; T. 1–2; Uniwersytet Ekonomiczny we Wrocławiu: Wrocław, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jończy, R. Migracje Zagraniczne z Obszarów Wiejskich Województwa Opolskiego po Akcesji Polski do Unii Europejskiej. Wybrane Aspekty Ekonomiczne i Demograficzne; Wydawnictwo Instytut Śląski: Opole, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jończy, R.; Rokitowska-Malcher, J. Płacowe Warunki Powrotu Migrantów Zarobkowych do Województwa Opolskiego; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego we Wrocławu: Wrocław, Poland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Jończy, R. (Ed.) Ekonomiczno-Społeczne Skutki Współczesnych Migracji w Wymiarze Regionalnym na Przykładzie Województwa Opolskiego; Wydawnictwo Instytut Śląski: Opole, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jończy, R.; Rokita-Poskart, D. Zmiany głównych kierunków migracji zagranicznych w latach 2007–2014 (na przykładzie studentów opolskiego ośrodka akademickiego). Stud. Ekon. 2016, 292, 80–88. [Google Scholar]

- Jończy, R. Regionalne skutki odpływu ludności Polski w okresie transformacji (wnioski z badań własnych w regionie opolskim). In Współczesne Polskie Migracje: STRATEGIE-Skutki Społeczne-Reakcja Państwa; Lesińska, M., Okólski, M., Eds.; Ośrodek Badań nad migracjami UW: Warszawa, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dolińska, A.; Jończy, R.; Śleszyński, P. Migracje Pomaturalne w Województwie Dolnośląskim Wobec Depopulacji Regionu i Wymogów Zrównoważonego Rozwoju Społeczno-Gospodarczego; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego we Wrocławiu: Wrocław, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Piecuch, T.; Piecuch, M. Analiza sytuacji młodych ludzi na rynku pracy—Rozważania teoretyczne i badania empiryczne. Mod. Manag. Rev. 2014, 19, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witczak-Roszkowska, D.; Okła, K. Skłonność studentów województwa świętokrzyskiego do zagranicznych emigracji zarobkowych. Pr. Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. We Wrocławiu 2015, 401, 555–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organiściak-Krzykowska, A. Współczesne uwarunkowania i kierunki migracji w Polsce. In Powroty z Migracji Wobec Sytuacji na Rynku Pracy w Polsce; Organiściak-Krzykowska, A., Ed.; UWM: Olsztyn, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalewska, G. Economic migration as an outcome of globalization and integration processes affecting the competitiveness of regions. Zesz. Nauk. Politech. Śląskiej. Organ. Zarządzanie 2019, 139, 243–256. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalewska, G.; Zabielska, I. Factors influencing the tendency of young people to migrate abroad—An example from Northern Poland/ Czynniki wpływające na skłonność do migracji zagranicznych osób młodych—Przykład z Polski Północnej. Econ. Reg. Stud. 2023, 16, 640–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perepeczko, B. Plany emigracyjne (wiejskiej) młodzieży. In Polska Wieś i Rolnictwo w Unii Europejskiej. Dylematy i Kierunki Przemian; Drygas, M., Rosner, A., Eds.; Instytut Rozwoju Wsi i Rolnictwa PAN: Warszawa, Poland, 2008; pp. 247–267. [Google Scholar]

- Kuźma, E. Migracje Polek z Obszarów Peryferyjnych Kraju do Metropolii Europejskich: Analiza Społecznych Konsekwencji Współczesnej Mobilności Przestrzennej Kobiet na Przykładzie Podlasianek w Brukseli. Referat na Konferencję pt. Młoda Polska Emigracja w UE Jako Przedmiot Badań Psychologicznych, Socjologicznych i Kulturowych; EuroEmigranci PL: Kraków, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos, A.G.; Fratsea, L.-M. Migrant and refugee impact on wellbeing in rural areas: Reframing rural development challenges in Greece. Front. Sociol. 2021, 6, 592750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurek, S. Typologia procesu starzenia się ludności miast i gmin Polski na tle jego demograficznych uwarunkowań. Przegląd Geogr. 2007, 79, 133–156. [Google Scholar]

- Rauziński, R. Wpływ uprzemysłowienia na migracje i wybór zawodu przez młodzież wiejską województwa opolskiego w latach 1950–1985. Stud. Społeczno-Ekon. 1979, 9, 307–328. [Google Scholar]

- Kupiszewski, M. Population Development 1980–1990 in Poland; Jordan, P., Ed.; (A Map with an Accompanying Text), [w:] Atlas of Eastern and Southeastern Europe; Vienna Oesterreichisches Ost-und Suedosteuropa Institut: Wiedeń, Poland, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kaczmarczyk, P.; Okólski, M. Demographic and Labour-market Impacts of Migration on Poland. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 2008, 24, 599–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janicki, W. Migracje Kompensacyjne Jako Czynnik Wzrostu Obszarów Peryferyjnych. In Rola Ukrytego Kapitału Ludzkiego; UMCS: Lublin, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Horolets, A.; Lesińska, M.; Okólski, M. Stan badań nad migracjami w Polsce na przełomie wieków. Próba diagnozy. Migr. Stud.—Rev. Pol. Diaspora 2019, 2, 7–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, J. The Theory of Wages; MacMillan: London, UK, 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, C.F. The Economics of Labor Migration. A Behavioral Analysis; Academic Press: London, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Kulischer, M.E. War and Population Changes, 1917–1947; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Fei, J.C.H.; Ranis, G. A theory of economic development. Am. Econ. Rev. 1961, 51, 533–565. [Google Scholar]

- Jandl, M. Is Migration Supply- or Demand-Determined? Some remarks on the ideological use of economic language. Int. Migr. 1994, 32, 467–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waldinger, R. The Making of an Immigrant Niche. Int. Migr. Rev. 1994, 28, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhning, W.R. Elements of Theory of International Migration to Industrial Nation States. In Global Trends in Migration: Theory and Research on International Population Movements; Kritz, M., Keely, C.B., Tomasi, S.M., Eds.; Center of Migration Studies: New York, NY, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Ravenstein, E.G. The Laws of Migration. J. Stat. Soc. Lond. 1885, 48, 167–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, C.J. Migration: A sociological problem. In Readings in the Sociology of Migration; Jansen, C.J., Ed.; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Janicki, W. Przegląd teorii migracji ludności. In Annales Universitatis Mariae Curie-Składowska, Sectio B, Geographia, Geologia, Mineralogia et Petrographia; UMCS: Lublin, Poland, 2007; Volume 62, pp. 285–304. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.S. A theory of migration. Demography 1966, 3, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Migration Group, 2021, Global-Migration-Ind. Available online: https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/Global-Migration-Indicators-2021_0.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- Henderson, R. Education, Training and Rural Living: Young People in Reydale. Educ. Train. 2005, 47, 183–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horváth, I. The Culture of Migration of Rural Romanian Youth. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2008, 34, 771–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, R.; Lulle, A.; Parutis, V.; Saar, M. Young Baltic Graduates Living and Working in London: From Peripheral Region to Escalator Region in Europe; Sussex Centre for Migration Research Working Paper Series; University of Sussex: Sussex, UK, 2015; Volume 82. [Google Scholar]

- Deotti, L.; Estruch, E. Addressing Rural Youth Migration at Its Root Causes: A Conceptual Framework; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Corbett, M.; Forsey, M. Rural Youth Out-migration and Education: Challenges to Aspirations Discourse in Mobile Modernity. Stud. Cult. Politics Educ. 2017, 38, 429–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, R.; Lulle, A.; Parutis, V.; Saar, M. From Peripheral Region to Escalator Region in Europe: Young Baltic Graduates in London. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2018, 25, 284–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, A.G.; Fratsea, L.-M. Aspirations, agency and well-being of Romanian migrants in Greece. Popul. Space Place 2022, 28, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leśniowska, J. Problem migracji polskiej kadry medycznej. Polityka Społeczna 2005, 4, 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kaczmarczyk, P. Współczesne Migracje Zagraniczne Polaków—Skala, Struktura Oraz Potencjalne Skutki dla Rynku Pracy; Ośrodek Badań nad Migracjami UW: Warszawa, Poland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kingma, M. Nurses on the move: A global overview. Health Res. Educ. Trust 2007, 42, 1281–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leśniowska, J. Migracje polskich pielęgniarek—Wstępne informacje. Polityka Społeczna 2008, 2, 19–21. [Google Scholar]

- Domagała, A. Kadry medyczne w ochronie zdrowia. Tendencje zmian w kraju i na świecie. Polityka Społeczna 2008, 7, 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Kautsch, M. Migracje personelu medycznego i ich skutki dla funkcjonowania systemu ochrony zdrowia w Polsce. Zdr. Publiczne I Zarządzanie 2013, 11, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haczyński, J.; Buraczyńska, M. Emigration of Polish Nurses—Reality and Consequences. Probl. Zarządzania 2018, 78, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, O.; Stilwell, B. Health professionals and migration. Bull. World Health Organ. 2004, 82, 560. [Google Scholar]

- Brush, B.L. Global nurse migration today. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2008, 40, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Report of the Supreme Council of Nurses and Midwives/Raport Naczelnej Rady Pielęgniarek i Położnych Zabezpieczenie Społeczeństwa Polskiego w Świadczenia Pielęgniarek i Położnych, Naczelna Izba Pielęgniarek i Położnych, Warszawa, Marzec. 2017. Available online: https://nipip.pl/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Raport_druk_2017.pdf (accessed on 7 August 2018).

- Wyrozębska, A.; Wyrozębski, P. Problematyka emigracji średniego personelu medycznego w aspekcie zarządzania zasobami ludzkimi w polskim systemie ochrony zdrowia. In Wkład Nauk Ekonomicznych w Rozwój Gospodarki Opartej na Wiedzy; Czerwonka, M., Ed.; Oficyna Wydawnicza SGH: Warszawa, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- El-Jardali, F.; Dimassi, H.; Dumit, N.; Jamal, D.; Mouro, G. A national cross-sectional study on nurses intent to leave and job satisfaction in Lebanon: Implications for policy and practice. BMC Nurs. 2009, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dywili, S.; Bonner, A.; O’Brien, L. Why do nurses migrate?—A review of recent. J. Nurs. Manag. 2013, 21, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pál, V.; Fabula, S.; Boros, L. Why Do Hungarian Health Workers Migrate? A Micro-Level Analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boros, L.; Dudás, G.; Ilcsikné Makra, Z.; Morar, C.; Pál, V. The migration of health care professionals from Hungary—Global flows and local responses. DETUROPE—Cent. Eur. J. Reg. Dev. Tour. 2022, 14, 164–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szpakowski, R.; Zając, P.W.; Dykowska, G.; Sienkiewicz, Z.; Augustynowicz, A.; Czerw, A. Labour migration of Polish nurses: A questionnaire survey conducted with the Computer Assisted Web Interview technique. Hum. Resour. Health 2016, 14 (Suppl. 1), 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żuk, P.; Żuk, P.; Lisiewicz-Jakubaszko, J. Labour migration of doctors and nurses and the impact on the quality of health care in Eastern European countries: The case of Poland. Econ. Labour Relat. Rev. 2019, 30, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domagała, A.; Kautsch, M.; Kulbat, A.; Parzonka, K. Exploration of Estimated Emigration Trends of Polish Health Professionals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domagała, A.; Kulbat, A.; Parzonka, K. Emigration from the perspective of Polish health professionals-insights from a qualitative study. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1075728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, R.L.; Patrician, P.A.; Bakitas, M.; Markaki, A. Palliative care integration: A critical review of nurse migration effect in Jamaica. BMC Palliat. Care 2021, 20, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pressley, C.; Newton, D.; Garside, J.; Simkhada, P.; Simkhada, B. Global migration and factors that suport acculturation and retention of international nurses: A systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. Adv. 2022, 4, 100083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botezat, A.; Incaltarau, C.; Nijkamp, P. Nurse migration: Long-run determinants and dynamics of flows in response to health and economic shocks. World Dev. 2024, 174, 106445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanimir, A. Skłonność do zagranicznej mobilności młodszych i starszych osób. Pr. Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. We Wrocławiu 2015, 385, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kowalewska, G.; Nieżurawska-Zając, J.; Rzeczkowski, D. Skłonności Społeczeństwa Informacyjnego do Migracji na Przykładzie Studentów Reprezentujących Pokolenie Y-Wyniki Badań Empirycznych; Roczniki Kolegium Analiz Ekonomicznych SGH: Warszawa, Poland, 2018; Volume 49, pp. 527–545. [Google Scholar]

- Smoleń, M.; Kędra, E.M. Plany zawodowe studentów kierunku Pielęgniarstwo Państwowej Medycznej Wyższej Szkoły Zawodowej w Opolu. Pielęgniarstwo Pol. 2018, 3, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamowicz, M.; Siedlanowski, P. Migracja jako uwarunkowanie rynku pracy w Polsce. In Rynek Pracy Wobec Wyzwań Przyszłości—Ujęcie Interdyscyplinarne; Siedlecka, A., Guzal-Dec, D., Eds.; Wydawnictwo PSW: Biała, Podlaska, 2021; pp. 24–47. [Google Scholar]

- Humphries, N.; Brugha, R.; Mcgee, H. Overseas nurse recruitment: Ireland as an illustration of the dynamic nature of nurse migration. Health Policy 2008, 87, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchan, J. Nurse migration and international recruitment. Nurs. Inq. 2001, 8, 203–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanisz, A. Modele regresji logistycznej. In Zastosowanie w Medycynie, Naukach Przyrodniczych i Społecznych; StatSoft Polska: Kraków, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rosner, A. Zmiany Rozkładu przestrzennego zaludnienia obszarów wiejskich. In Wiejskie Obszary Zmniejszające Zatrudnienie i Koncentrujące Ludność Wiejską; Instytut Rozwoju Wsi i Rolnictwa: Warsaw, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Narodowy Spis Powszechny Ludności i Mieszkań; Raport z Wyników, Marzec 2011; GUS: Warszawa, Poland, 2012; Volume 102.

- Brzozowski, J.; Kaczmarczyk, P. Konsekwencje Migracji Poakcesyjnych z Polski dla Kompetencji Zawodowych i Kulturowych Polskiego Społeczeństwa; Ekspertyza Komitetu Badań nad Migracjami PAN: Warszawa, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Migracje Zagraniczne na Pobyt Czasowy—Wyniki NSP. 2021. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/spisy-powszechne/nsp-2021/nsp-2021-wyniki-ostateczne/migracje-zagraniczne-na-pobyt-czasowy-wyniki-nsp-2021,4,1.html (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Cai, X.; Zhang, D.; Jin, Y. Understanding the Push-Pull Factors for Joseonjok (Korean-Chinese) Students Studying in South Korea. Sustainability 2024, 16, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarczyk, P.; Tyrowicz, J. Migracje Osób z Wysokimi Kwalifikacjami; Fundacja Inicjatyw Społeczno-Ekonomicznych: Warszawa, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bożek, J.; Szewczyk, J.; Jaworska, M. Poziom rozwoju gospodarczego województw w ujęciu dynamicznym. Rozw. Reg. I Polityka Reg. 2021, 57, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://nipip.pl/liczba-pielegniarek-poloznych-zarejestrowanych-zatrudnionych/ (accessed on 7 July 2020).

- OECD. Stat. Available online: https://stats.oecd.org/ (accessed on 19 April 2023).

- Wójcik, G.; Sienkiewicz, Z.; Wrońska, I. Migracja zawodowa personelu pielęgniarskiego jako nowe wyzwanie systemów ochrony zdrowia. Probl. Pielęgniarstwa 2007, 15, 120–127. [Google Scholar]

- Wysokiński, M.; Fidecki, W.; Walas, L.; Ślusarz, R.; Sienkiewicz, Z.; Sadurska, A.; Kachaniuk, H. Satysfakcja z życia polskich pielęgniarek. Probl. Pielęgniarstwa 2009, 17, 167–172. [Google Scholar]

- Horgen, F.J.; Napierała, J. Polscy migranci w Norwegii. In Mobilność i Migracje w Dobie Transformacji, Wyzwania Metodologiczne; Kaczmarczyk, P., Ed.; Wydawnictwo Naukowe Scholar: Warszawa, Poland, 2011; pp. 38–67. [Google Scholar]

- Babiarczyk, B.; Swół, J.; Schlegel-Zawadzka, M. Analiza sytuacji polskich pielęgniarek pracujących za granicą. Probl. Pielęgniarstwa 2014, 22, 130–135. [Google Scholar]

- Binkowska-Bury, M.; Nagórska, M.; Januszewicz, P.; Ryżko, J. Migracje Pielęgniarek i Położnych—Problemy i Wyzwania; Przegląd Medyczny Uniwersytetu Rzeszowskiego i Narodowego Instytutu Leków w Warszawie: Warsaw, Poland, 2010; Volume 4, pp. 497–504. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).