Corporate Social Responsibility and Consumer Behavior in Sports: Exploring and Adapting a Participatory Sports Scale

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Assessment Tools of Corporate Social Responsibility Initiatives

2.2. Corporate Social Responsibility in the Field of Sports

2.3. Customer Trust, Loyalty, and CSR Initiatives

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sampling and Data Collection

3.2. Measurement Tools

| Constructs | Items | References |

|---|---|---|

| Corporate social responsibility (CSR) | The tennis club I am a member of…. | Park et al. (2015) [52] |

| … strives to raise funds for social causes (CSR1) … encourages its employees/partners to participate in voluntary activities in local communities (CSR2) … supports sports and cultural events (CSR3) … endeavours to participate in environmental campaigns (CSR4) … attempts to reduce waste and use environmentally friendly products (CSR5) … tries to reduce the consumption of energy and natural resources (CSR6) … attempts to create new jobs (CSR7) … tries to contribute to society and the economy by investing and creating profit (CSR8) … tries to help the economic development of the country by adding some value (CSR9) | ||

| Loyalty | How likely do you think it is to…. | Oliver (1999) [87] |

| … continue to come to training at this club? | ||

| … make positive comments about the club to friends | ||

| … recommend the club when people ask for your opinion | ||

| … encourage friends and family to join the club | ||

| Trust | How likely do you think it is to…. | Chaudhuri and Holbrook (2001) [61] |

| … trust the club | ||

| … rely on the club | ||

| … consider the club healthy | ||

| … feel a sense of security in the club |

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model

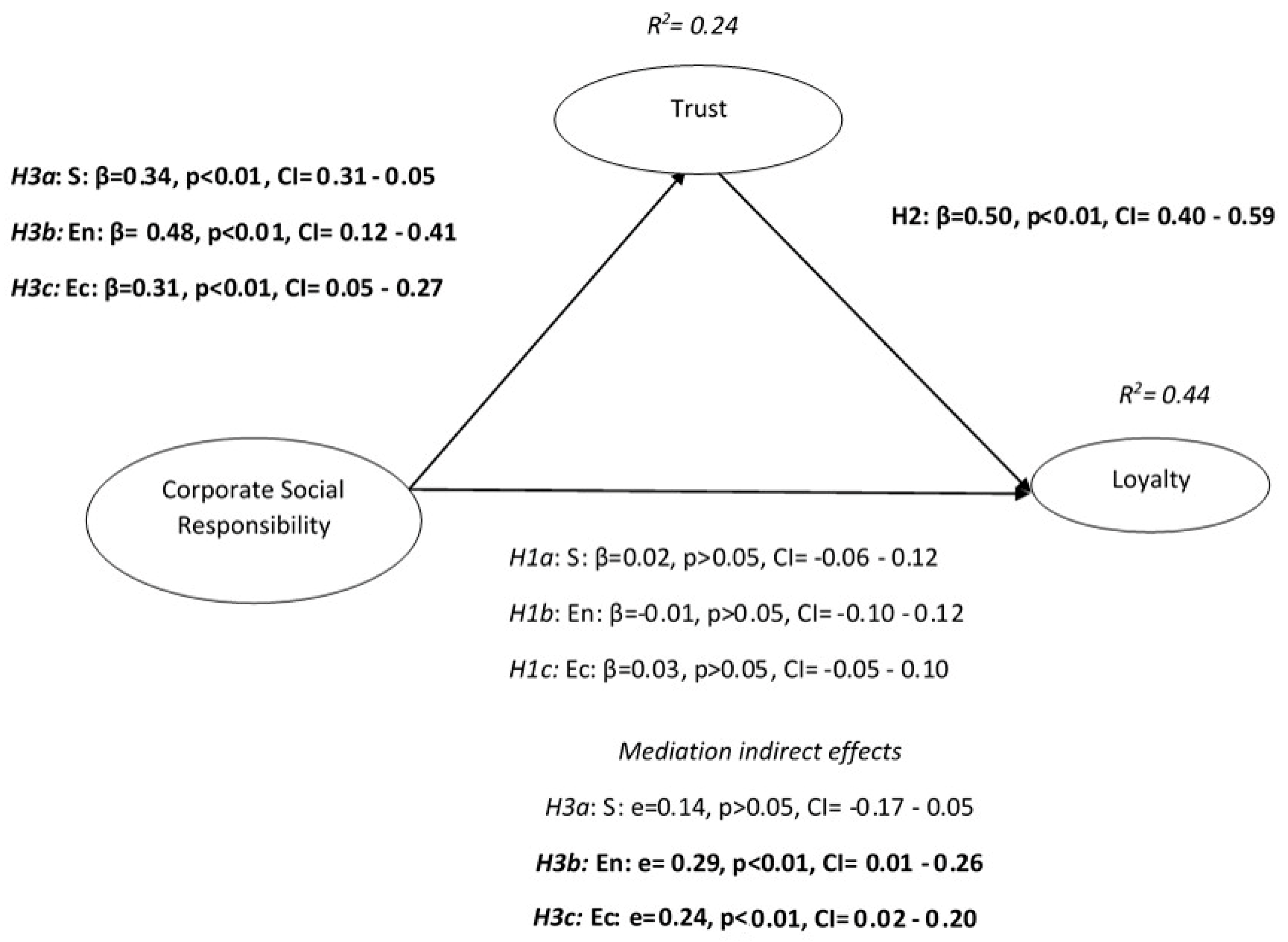

4.2. Hypothesized Model

5. Discussion

Theoretical and Practical Implications

6. Conclusions

7. Study’s Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McCullough, B.P.; Orr, M.; Kellison, T. Sport ecology: Conceptualizing an emerging sub discipline within sport management. J. Sport Manag. 2020, 34, 509–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swatuk, L.A.; Thomas, B.K.; Wirkus, L.; Krampe, F.; Batista da Silva, L.P. The ‘boomerang effect’: Insights for improved climate action. Clim. Dev. 2020, 13, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, G.; Chadwick, S. Corporate Citizenship in Football: Delivering Strategic Benefits through Stakeholder Engagement. Manag. Decis. 2009, 47, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamil, S.; Walters, G.; Watson, L. The Model of Governance at FC Barcelona: Balancing Member Democracy, commercial Strategy, Corporate Social Responsibility and Sporting Performance. Soccer Soc. 2010, 11, 475–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendt, S.; Brettel, M. Understanding the influence of corporate social responsibility on corporate identity, image, and firm performance. Manag. Decis. 2010, 48, 1469–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaaij, R.; Westerbeek, H. Sport business and social capital: A contradiction in terms? Sport Soc. 2010, 13, 1356–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trendafilova, S.; Ziakas, V.; Sparvero, E. Linking CSR in sport with community development: An added source of community value. Sport Soc. 2017, 20, 938–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D.; Karam, C. Corporate Social Responsibility in Developing Countries as an Emerging Field of Study. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2018, 20, 32–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreck, P.; Raithel, S. Corporate Social Performance, Firm Size, and Organizational Visibility: Distinct and Joint Effects on Voluntary Sustainability Reporting. Bus. Soc. 2018, 57, 742–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnett, C. Globalized Sport and Development from a Commonwealth Perspective. In The Palgrave Handbook of Globalization and Sport; Maguire, J., Liston, K., Falcous, M., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millington, R.; Giles, A.R.; Hayhurst, L.M.C.; van Luijk, N.; McSweeney, M. ‘Calling out’ corporate redwashing: The extractives industry, corporate social responsibility and sport for development in indigenous communities in Canada. Sport Soc. 2019, 22, 2122–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E. Corporate social responsibility as a determinant of corporate reputation in the airline industry. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 47, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walzel, S.; Robertson, J.; Anagnostopoulos, C. Corporate Social Responsibility in Professional Team Sports Organizations: An Integrative Review. J. Sport Manag. 2018, 32, 511–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Y.; Kent, A. A Conceptual Framework for Understanding the Effects of Corporate Social Marketing on Consumer Behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 121, 621–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitbarth, T.; Walzel, S.; Anagnostopoulos, C.; van Eekeren, F. Corporate social responsibility and governance in sport: “Oh, the things you can find, if you don’t stay behind! Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2015, 15, 254–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salcines, J.L.P.; Babiak, K.; Walters, G. (Eds.) Routledge Handbook of Sport and Corporate Social Responsibility, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, M.K.; Cronin, J.J., Jr. Some new thought on conceptualizing perceived service quality: A hierarchical approach. J. Mark. 2009, 65, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.; Millington, A. Does it pay to be different? An analysis of the relationship between corporate social and financial performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2008, 29, 1325–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, C. Strategic Responses to Institutional Processes. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1991, 16, 145–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamir, B.; Eilam, G. “What’s Your Story?” to Life-Stories Approach to Authentic Leadership Development. Leadersh. Q. 2005, 16, 395–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, P.C. Corporate Social Responsibility in Sport: An Overview and key issues. J. Sport Manag. 2009, 23, 698–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, M.; Kent, A. Do Fans Care? Assessing the Influence of Corporate Social Responsibility on Consumer Attitudes in the Sport Industry. J. Sport Manag. 2009, 23, 743–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, B.J.; Lee, L.W.; Oh, C.H. The Impact of CSR on Consumer-Corporate Connection and Brand Loyalty: A Cross Cultural Investigation. Int. Mark. Rev. 2015, 32, 518–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, H.; Babiak, K. Beyond the Game: Perceptions and Practices of Corporate Social Responsibility in the Professional Sport Industry. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 91, 433–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadowska, B.; Lulek, A. Management of manufacturing resources in an enterprise on the example of human resources. Acta Sci. Pol. Oecon. 2020, 19, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torelli, R. Sustainability, Responsibility and Ethics: Different Concepts for a Single Path. Soc. Responsib. J. 2021, 17, 719–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Xiao, J.; Tang, X.; Li, J. How sustainable marketing influences the customer engagement and sustainable purchase intention? The moderating role of corporate social responsibility. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1128686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, M.L.; Henriques, I.; Husted, M.B. Beyond good intentions: Designing CSR initiatives for greater social impact. J. Sport Manag. 2020, 46, 937–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anagnostopoulos, C.; Byers, T.; Shilbury, D. Corporate social responsibility in professional team sport organisations: Towards a theory of decision-making. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2014, 14, 259–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babiak, K.; Wolfe, R. More than a just a game? Corporate Social Responsibility and Super Bowl XL. Sport Manag. Rev. 2006, 9, 296–318. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Action Plan on Physical Activity 2018–2030: More Active People for a Healthier Word; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Moradi, J.; Bahrami, A.; Dana, A. Motivation for Participation in Sports Based on Athletes in Team and Individual Sports. Phys. Cult. Sport Stud. Res. 2020, 85, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaaij, R.; Knoppers, A.; Jeanes, R. “We want more diversity but…”: Resisting diversity in recreational sports clubs. Sport Manag. Rev. 2020, 23, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakidou, A.; Tsitskari, E.; Lagoudaki, G. Evaluation of Corporate Social Responsibility Actions by Participants in Exercise and Recreation Programs at a Swimming Pool. The case of programs by YMCA. In Proceedings of the 4th Congress on Sports Tourism, Dance & Recreation, Komotini, Greece, 10–11 February 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Le Noury, P.; Buszard, T.; Reid, M.; Farrow, D. Examining the representativeness of a virtual reality environment for simulation of tennis performance. J. Sports Sci. 2020, 39, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonseca Morales, A.; Martínez-Gallego, R. Teaching tactics in tennis. A constraint-based approach proposal. ITF Coach. Sport Sci. Rev. 2021, 29, 6–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyei, J.; Sun, S.; Penney, E.K.; Abrokwah, E.; Agyare, R. Understanding CSR and customer loyalty: The role of customer engagement. J. Afr. Bus. 2022, 23, 869–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, M.; Brock, W.; Hansen, L.P. Pricing uncertainty induced by climate change. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2020, 33, 1024–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A. The Pyramid of Corporate Social Responsibility: Toward the Moral Management of Organizational Stakeholders. Bus. Horiz. 1991, 34, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H.; Glavas, A. What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility: A review and research agenda. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 932–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.J. Corporate social performance revisited. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1991, 16, 691–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.J. Measuring corporate social performance: A review. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 50–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Towards the Sustainable Corporation: Win-Win-Win Business Strategies for Sustainable Development. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1994, 36, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slaper, T.; Hall, T.J. The Triple Bottom Line: What is it and how does it work. Ind. Bus. Rev. 2011, 86, 4–8. [Google Scholar]

- Maignan, I. Consumer’s Perceptions of Corporate Social Responsibilities: A Cross Cultural Comparison. J. Bus. Ethics 2001, 30, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maignan, I.; Ferrell, O.C. Nature of Corporate Responsibilities Perspectives from American, French, and German Consumers. J. Bus. Res. 2002, 56, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Chaiy, C.; Chaiy, S. Developing a Corporate Social Responsibility Process Scale of individual stakeholder’s perception. In 2012 AMA Educator’s Proceedings. Marketing in the Socially-Networked World: Challenges of Emerging Stagnant, and Resurgent Markets; American Marketing Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 2012; Volume 23, ISSN 0888-1839. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, J.; de los Salmones Sanchez, M.D.M.G.; del Bosque, I.R. Understanding corporate social responsibility and product perceptions in consumer markets: A cross-cultural evaluation. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 80, 597–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Misra, M. Linking corporate social responsibility (CSR) and organizational performance: The moderating effect of corporate reputation. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2021, 27, 100–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turker, D. Measuring corporate social responsibility: A scale development study. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 85, 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, L.M.; Hung Lai, C. Impact of corporate social responsibility initiatives on Taiwanese banking customers. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2011, 29, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; Lee, S.; Kwon, S.J.; Del Pobil, A.P. Determinants of behavioral intention to use South Korean airline services: Effects of service quality and corporate social responsibility. Sustainability 2015, 7, 12106–12121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maignan, I.; Ferrell, O.C.; Hult, G.T.M. Corporate citizenship: Cultural antecedents and business benefits. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1999, 27, 455–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, D.J.; Mohr, L.A.; Harris, K.E. A re-examination of socially responsible consumption and its measurement. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 989–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, G.; Bartikowski, B. Exploring corporate ability and social responsibility associations as antecedents of customer satisfaction cross-culturally. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 989–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnam, M.; Anagnostopoulos, C.; Byers, T.; Papadimitriou, D.A. The impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on value-in-use through customer engagement in non-profit sports clubs: The moderating role of co-production. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2023, 23, 789–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casper, J.M.; McCullogh, B.P.; Kushner Smith, D.M. Pro-environmental sustainability and political affiliation: An examination of USA College sport sustainability efforts. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Y.; Kent, A. A Conceptual Framework for Understanding the Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility on Consumer Behavior in the Sport Industry. J. Sport Manag. 2014, 28, 417–432. [Google Scholar]

- Anagnostopoulos, C.; Winand, M.; Papadimitriou, D.; Zeimers, G. Implementing corporate social responsibility through charitable foundations in professional football: The role of trustworthiness. Manag. Sport Leis. 2022, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, F.; Wu, Y.; Mehmood, K.; Jabeen, F.; Iftikhar, Y.; Acevedo-Duque, Á.; Kwan, H.K. Impact of Spectators’ Perceptions of Corporate Social Responsibility on Regional Attachment in Sports: Three-Wave Indirect Effects of Spectators’ Pride and Team Identification. Sustainability 2021, 13, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, A.; Holbrook, M. The Chain of Effects From Brand Trust and Brand Affect to Brand Performance: The Role of Brand Loyalty. J. Mark. 2001, 65, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaveli, N.; Papadimitriou, D.; Karagiorgos, T.; Alexandris, K. Exploring the role of fitness instructors’ interaction quality skills in building customer trust in the service provider and customer satisfaction. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2021, 23, 767–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.; Hunt, S. The Commitment-Trust Theory of Relationship Marketing. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, W.; Kantsperger, R. Consumer Trust in Service Companies: A Multiple Mediating Analysis. Manag. Serv. Qual. 2010, 20, 4–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filo, K.; Funk, D.; Alexandris, K. Exploring the role of brand trust in the relationship between brand associations and brand loyalty in sport and fitness. Int. J. Sport Manag. Mark. 2008, 3, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.Y. Effect of restaurant brand trust on brand relationship quality-focused on the mediating effect of brand promise. Korean J. Food Nutr. 2020, 33, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanveer, M.; Ahmad, A.R.; Mahmood, H.; Haq, I.U. Role of Ethical Marketing in Driving Consumer Brand Relationships and Brand Loyalty: A Sustainable Marketing Approach. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-C.; Khan, A.; Hongsuchon, T.; Ruangkanjanases, A.; Chen, Y.-T.; Sivarak, O.; Chen, S.-C. The Role of Corporate Social Responsibility and Corporate Image in Times of Crisis: The Mediating Role of Customer Trust. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A.; Fernandes, T. Understanding customer brand engagement with virtual social communities: A comprehensive model of drivers, outcomes and moderators. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2018, 26, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoeffler, S.; Keller, K. Building Brand Equity Through Corporate Societal Marketing. J. Public Policy Mark. 2002, 21, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavas, A.; Godwin, L. Is the Perception of ‘Goodness’ Good Enough? Exploring the Relationship Between Perceived Corporate Social Responsibility and Employee Organizational Identification. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatma, M.; Khan, I. Impact of CSR on Customer Citizenship Behavior: Mediating the Role of Customer Engagement. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, W.M.; Moon, T.W.; Kim, H. When does customer CSR perception lead to customer extra-role behaviors? The roles of customer spirituality and emotional brand attachment. J Brand Manag. 2020, 27, 421–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliburton, C.; Poenaru, A. The Role of Trust on Consumer Relationship; ESCP Europe Business School: Paris, France, 2010; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Jalilvand, M.R.; Salimipour, S.; Elyasi, M.; Mohammadi, M. Factors influencing word of mouth behaviour in the restaurant industry. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2017, 35, 81–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, O.; Markovic, S.; Bagherzadeh, M.; Singh, J. Co-creation: A Key Link Between Corporate Social Responsibility, Customer Trust, and Customer Loyalty. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 163, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-s.; Baek, W.-y.; Byon, K.K.; Ju, S.-b. Creating Shared Value and Fan Loyalty in the Korean Professional Volleyball Team. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyadzayo, M.W.; Leckie, C.; McDonald, H. CSR, relationship quality, loyalty and psychological connection in sports. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2016, 34, 883–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi Boroujerdi, S.; Mansouri, H.; Hasnah Hassan, S.; Nadri, Z. The Influence of Team Social Responsibility in the attitudinal loyalty of football fans: The mediating role of team identity and team trust. Asian J. Sport Hist. Cult. 2023, 2, 350–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtulan, A.; Begeç, S. Effects of Social Responsibility Practices on the Brand Image, Brand Awareness, and Brand Loyalty of Sponsor Businesses: A Study on Sports Clubs. Economics 2023, 17, 20220055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misener, K.; Babiak, K. A new ‘arena’: Social responsibility through community sport. In Proceedings of the Conference of the North American Society for Sport Management Conference (NASSM), Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2–6 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, E.; Milkman, K.; Gromet, D.; Rebele, R.; Massey, C.; Duckworth, A.; Grant, A. The mixed effects of online diversity training. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 16, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; Kim, K.J.; Kwon, S.J. Corporate social responsibility as a determinant of consumer loyalty: An examination of ethical standard, satisfaction and trust. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 76, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etikan, I.; Musa, S.A.; Alkassim, R.S. Comparison of Convenience Sampling and Purposive Sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2016, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banville, D.; Desrosiers, P.; Genet-Volet, Y. Translating Questionnaires and Inventories Using a Cross-Cultural Translation Technique. J. Teach. Phys. Ed. 2000, 19, 374–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallerand, R.J. Vers une méthodologie de validation trans-culturelle de questionnaires psychologiques: Implications pour la recherche en langue française. Can. Psychol. 1989, 30, 662–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Whence Consumer Loyalty. J. Mark. 1999, 63, 33–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsitskari, E.; Tzetzis, G.; Konsoulas, D. Perceived Service Quality and Loyalty of Fitness Centers’ Customers: Segmenting Members Through Their Exercise Motives. Serv. Mark. Q. 2017, 38, 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with Amos: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 2nd ed.; Taylor and Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2010; p. 416. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.A. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research, 2nd ed.; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015; p. 462. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sato, M.; Du, J.; Inoue, Y. Rate of physical activity and community health: Evidence from U.S. counties. J. Phys. Act. Health 2016, 13, 640–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, S.C.; Strosahl, K.D.; Wilson, K.G. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: The Process and Practice of Mindful Change, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cortina, J.M. What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 78, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, L.; Boyd, C.P.; Sewell, J. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for the Treatment of Adolescent Depression: A Pilot Study in a Psychiatric Outpatient Setting. Mindfulness 2011, 2, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S.; Korschun, D. Using corporate social responsibility to win the war for talent. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2008, 49, 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Du, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Maximizing business returns to corporate social responsibility (CSR): The role of CSR communication. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatma, M.; Rahman, Z.; Khan, I. Building company reputation and brand equity through CSR: The mediating role of trust. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2015, 33, 840–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Fatma, M. CSR Influence on Brand Image and Consumer Word of Mouth: Mediating Role of Brand Trust. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pivato, S.; Misani, N.; Tencati, A. The impact of corporate social responsibility on consumer trust: The case of organic food. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2008, 17, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Y.; Funk, D.C.; McDonald, H. Predicting behavioral loyalty through corporate social responsibility: The mediating role of involvement and commitment. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 75, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbu, M.C.R.; Popescu, M.C.; Burcea, G.B.; Costin, D.-E.; Popa, M.G.; Păsărin, L.-D.; Turcu, I. Sustainability and Social Responsibility of Romanian Sport Organizations. Sustainability 2022, 14, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factors/Facets | Loadings | t-Value | SMC | Alpha | Mean | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social | 0.89 | 3.39 | 0.72 | 0.89 | |||

| … strives to raise funds for social causes (CSR1) | 0.87 | 11.21 *** | 0.78 | ||||

| … encourages its employees/partners to participate in voluntary activities in local communities (CSR2) | 0.82 | 8.36 *** | 0.67 | ||||

| … supports sports and cultural events (CSR3) | 0.86 | 10.26 *** | 0.78 | ||||

| Environment | 0.90 | 3.33 | 0.75 | 0.90 | |||

| … endeavours to participate in environmental campaigns (CSR4) | 0.88 | 12.02 *** | 0.77 | ||||

| … attempts to reduce waste and use environmentally friendly products (CSR5) | 0.84 | 13.47 *** | 0.70 | ||||

| … tries to reduce the consumption of energy and natural resources (CSR6) | 0.88 | 12.23 *** | 0.76 | ||||

| Economic | 0.90 | 3.41 | 0.77 | 0.91 | |||

| … attempts to create new jobs (CSR7) | 0.88 | 13.66 *** | 0.71 | ||||

| … tries to contribute to society and the economy by investing and creating profit (CSR8) | 0.92 | 16.71 *** | 0.86 | ||||

| … tries to help the economic development of the country by adding some value (CSR9) | 0.82 | 13.98 *** | 0.67 | ||||

| Trust | 0.91 | 4.33 | 0.70 | 0.90 | |||

| … trust the club | 0.81 | 14.81 *** | 0.71 | ||||

| … rely on the club | 0.79 | 11.65 *** | 0.69 | ||||

| … consider the club healthy | 0.88 | 17.55 *** | 0.79 | ||||

| … feel a sense of security in the club | 0.83 | 13.21 *** | 0.73 | ||||

| Loyalty | 0.92 | 4.60 | 0.76 | 0.92 | |||

| … continue to come to training at this club? | 0.77 | 10.23 *** | 0.70 | ||||

| … make positive comments about the club to friends | 0.91 | 18.03 *** | 0.86 | ||||

| … recommend the club when people ask for your opinion | 0.87 | 12.88 *** | 0.78 | ||||

| … encourage friends and family to join the club | 0.88 | 13.93 *** | 0.79 |

| Factors | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.837 | ||||

| 0.327 | 0.854 | |||

| 0.442 | 0.789 | 0.851 | ||

| 0.443 | 0.726 | 0.468 | 0.880 | |

| 0.656 | 0.333 | 0.307 | 0.398 | 0.847 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lagoudaki, G.; Tsitskari, E.; Karagiorgos, T.; Yfantidou, G.; Tzetzis, G.; Tsiotras, G. Corporate Social Responsibility and Consumer Behavior in Sports: Exploring and Adapting a Participatory Sports Scale. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5825. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16145825

Lagoudaki G, Tsitskari E, Karagiorgos T, Yfantidou G, Tzetzis G, Tsiotras G. Corporate Social Responsibility and Consumer Behavior in Sports: Exploring and Adapting a Participatory Sports Scale. Sustainability. 2024; 16(14):5825. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16145825

Chicago/Turabian StyleLagoudaki, Georgia, Efi Tsitskari, Thomas Karagiorgos, Georgia Yfantidou, George Tzetzis, and George Tsiotras. 2024. "Corporate Social Responsibility and Consumer Behavior in Sports: Exploring and Adapting a Participatory Sports Scale" Sustainability 16, no. 14: 5825. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16145825

APA StyleLagoudaki, G., Tsitskari, E., Karagiorgos, T., Yfantidou, G., Tzetzis, G., & Tsiotras, G. (2024). Corporate Social Responsibility and Consumer Behavior in Sports: Exploring and Adapting a Participatory Sports Scale. Sustainability, 16(14), 5825. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16145825