Abstract

There is a strong relationship between heritage-led urban regeneration and the UN initiatives for Sustainable Development (SD). These include the Intangible Cultural Heritage Convention (ICH; 2003) and Historic Urban Landscape (HUL; 2011) under the UNESCO mandate and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs; 2015) and the New Urban Agenda (NUA; 2016) under the UN mandate. Despite the presence of those initiatives, regeneration in a World Heritage city often leads to the disappearance of intangible heritage, gentrification, excessive tourism, and social exclusion. Therefore, this paper critically identifies the shortcomings of those initiatives in addressing social and cultural sustainability. It uses the recently inscribed city of As-Salt on the WHL to showcase how the relevant SDGs’ targets and indicators are problematic in monitoring and measuring the sustainability of urban regeneration practices in WH cities. This is achieved by investigating where heritage and culture are embedded within the descriptions of goals and indicators in the three initiatives (SDGs, NUA, and HUL) document. A content analysis, using the NVivo qualitative data analysis tool, was conducted in order to identify complementarity, synergies, and correlations among the goals and indicators related to social and cultural sustainability. This paper concludes by suggesting an integrated approach under the umbrella of the SDGs for a more sustainable heritage-led urban regeneration alternative for cities acquiring UNESCO WH status.

1. Introduction

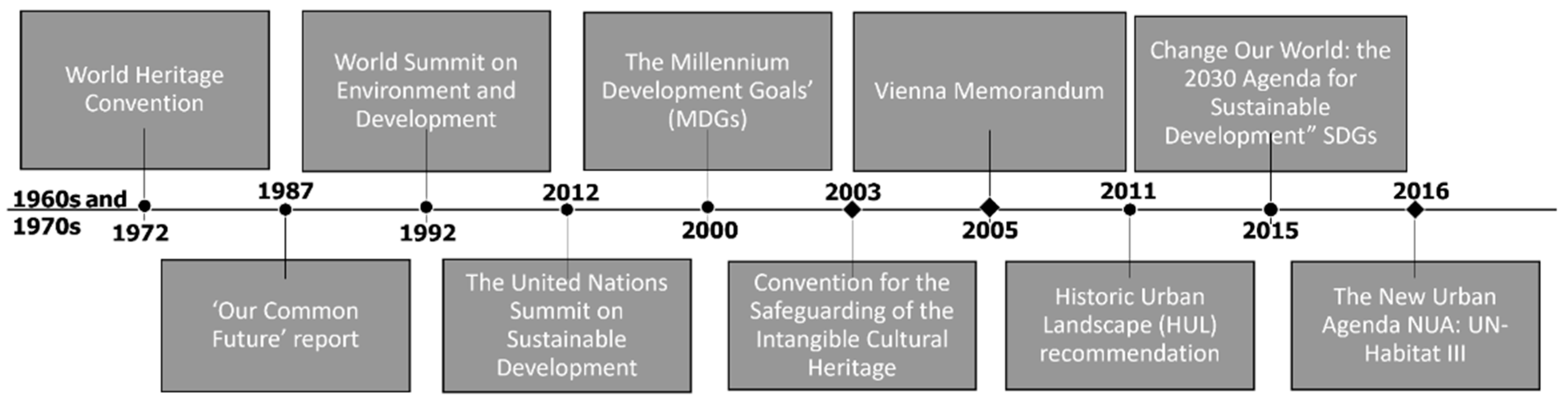

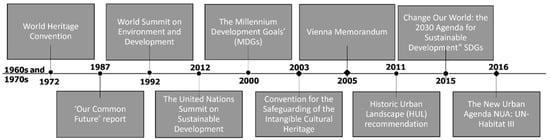

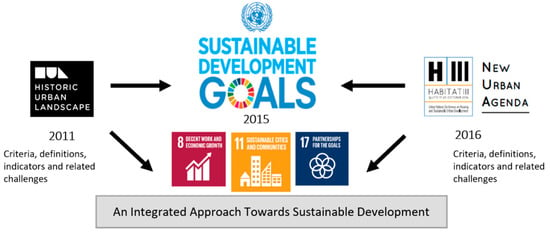

One of the main concerns of the United Nations (UN) is sustainable development, which is defined as a “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs and aspirations” [1], p. 47. It aims at creating a state of equilibrium across the four interdependent sustainability pillars: economic, environmental, social, and cultural sustainability [2,3,4]. Heritage-led urban regeneration has an important relationship to many UN initiatives for sustainable development. Heritage can play a pivotal role in relating to one another and imagining a possible and sustainable future. Sustainable development is not the opposite of economic growth; it emphasizes transforming economic growth patterns and coordinating resource use, substitution, and regeneration [2,5]. Therefore, the UN has issued many initiatives, conventions, and memorandums to follow that quest. These are presented in the timeline in Figure 1 below. Upon reviewing the corpus of the UN initiatives for sustainable development, this paper particularly investigates where social and cultural sustainability appears in the UN 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), identifying SDGs 8, 11, and 17 [6]; the Historical Urban Landscape Recommendations (HUL) [7]; and the New Urban Agenda (NUA) [8].

Figure 1.

The corpus of the UN (United Nations) initiatives for sustainable development Source: creation of the first author.

By examining the typical heritage-led urban regeneration that follows once an urban setting is nominated and inscribed on the WHL, the paper illustrates how, despite the three UN initiatives in focus, social and cultural sustainability remains a major weakness that can jeopardize the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) Outstanding Universal Value (OUV). Despite the existence of various UN sustainable development initiatives, regeneration in WH cities is often translated to a proliferation of hotels, bed-and-breakfast accommodations, souvenir shops, and many other tourist-oriented leisure and catering facilities [9]. Urban regeneration that follows the nomination of a city on the WHL will attempt to celebrate and consume the values assigned to the city’s OUV [10]. In doing so, other heritage values are excluded in the process, while new urban issues are unintentionally provoked, such as gentrification, excessive tourism, and social exclusion, amongst many others [11,12,13,14,15]. The UN sustainable development initiatives that followed the UNESCO World Heritage Convention—mainly the SDGs—have failed to address these issues. This is due to their shortcomings in addressing social and cultural sustainability as at least an equal pillar to economic and environmental sustainability, if not the central pillar. Social sustainability promotes social inclusion of the poor and vulnerable by empowering people, building cohesive and resilient societies, and making institutions accessible and accountable to citizens [16]. On the other hand, cultural sustainability is considered a source to identify the connection of a local sense of place and to provide legitimate reasons for preserving heritage for future generations [17]. Subsequently, the underrepresentation of social and cultural sustainability impacts the vital connections between tangible and intangible heritage, which are crucial to urban resilience. This creates a potential conflict between the heritage preservation for all humankind offered by UNESCO WHL and the implementation of Sustainable Development, also established by the United Nations UN. While all mentioned initiatives, including the WH convention, include the protection of cultural heritage and improving the lifestyle of local communities, adopting WH listing criteria and other criteria under the UN umbrellas might lead to a potential conflict of interest in the same urban site.

Furthermore, although the lack of addressing social and cultural sustainability was acknowledged well before the SDGs, the new platforms did not address this issue [7,18,19,20]. The potential to operationally relate culture and heritage to the SDGs remains untapped in national and local strategies despite the efforts of many platforms dedicated to integrating and localizing culture among the SDGs [21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. Investigating how the UN and the UNESCO World Heritage List highlighted these aspects is necessary to understand why these two parameters were overlooked and what measures can be taken to ensure their inclusion. It was concluded that the applicability of the SDGs to be translated into tangible and localized measures could have many embedded obstacles and form a barrier that should be derived from the local community’s needs [21,26,27]. These challenges include difficulties in attaining adequate data and developing systematic methodologies for cultural heritage to realize and measure the progress of the SDGs. Therefore, this paper critically investigates and identifies the shortcomings of those initiatives in addressing social and cultural sustainability, particularly within the SDGs. It shows how the relevant SDG targets and indicators are problematic in monitoring and measuring the sustainability of urban regeneration practices in WH cities, thus justifying why a sustainable alternative is still needed to rebalance cultural and social priorities in SDGs.

2. Materials and Methods

The methodology adopted in this research is based on three research aims:

- To critically investigate and position heritage and culture within the UN Sustainable Development Goals 2030, namely SDGs 8, 11, and 17, as the most related goals to heritage-led urban regeneration. This will allow for the identification of the specific criteria and values embedded in each goal and their current shortcomings in addressing social and cultural sustainability.

- To use the city of As-Salt in Jordan as a timely case study due to its recent inscription in July 2021 on the UNESCO WHL to illustrate the contradictions in prioritizing social and cultural sustainability within the SDGs with the urban regeneration practices there. The city has gone through two attempts to be inscribed on the WHL in the last decade: one in 2016, focusing on the tangible heritage; and another in 2020, shifting the focus on the city’s intangible heritage, which led to the successful inscription on the WHL [28]. These two attempts have triggered an increasing interest from investors in both the public and private sectors to initiate a series of uncoordinated urban development projects and tourism-oriented facilities at the expense of the local community’s needs [9]. Thus, this case is a good example of the contradictions in prioritizing social and cultural sustainability that may arise from pursuing the WH listing and addressing SDGs.

- To address the shortcomings of the SDGs by integrating relevant and complementary articles and commitments from the Historic Urban Landscape (HUL), previously introduced in 2011, and its subsequent New Urban Agenda (NUA), introduced in 2016. This is performed in the following three phases: (1) positioning where the NUA and HUL overlap with the SDGs relevant target to heritage and culture (SDGs 8, 11 and 17); (2) conducting a critical content analysis using the NVivo qualitative analysis tool to analyze the overlap and synergies between the three initiatives and see how these can be combined and incorporated to complement the SDGs’ targets; and (3) data curation—a refined definition for the targets and new indicators was created. This is done to develop a refined set of criteria and targets of the SDGs for mainly historic cities and WH cities.

3. Heritage-Led Urban Regeneration and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 2015

Following the end of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs)’s implementation period in 2015, the UN Summit on Sustainable Development ended with “Change Our World: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development” [6]. Seventeen Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were introduced as landmark achievements to offer a new type of international consensus to promote a sustainable development vision from a global standpoint [29]. Heritage-led urban regeneration has an important relationship to the SDGs, especially SDG 11: “Sustainable cities and communities: Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable” [6], p. 24. Unfortunately, out of 17 goals for sustainable development, with 169 targets embedded in the goals, cultural heritage was explicitly mentioned only in target 11.4: “Protect the world’s cultural and natural heritage- Strengthen efforts to protect and safeguard the world’s cultural and natural heritage” [6], p. 24. However, it was implied in many other targets within SDG 8, “promote sustained, inclusive, and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment, and decent work for all”; and SDG 17, “Revitalize the global partnership for sustainable development” [6], p. 21.

The end of 2023 marked eight years since the SDGs were first introduced. The subsequent progress reports published by the UN official website indicate that the SDGs have gone a long way in regard to the aspects of providing basic needs like shelter, transportation, pollution, and waste management [30]. However, safeguarding and promoting cultural heritage were clearly under-represented and not sufficiently emphasized. This is even though social and cultural sustainability are indirectly embedded in many SDGs, such as safe and sustainable cities, decent work and economic growth, reduced inequalities, the environment, and promoting gender equality and peaceful and inclusive societies. These weaknesses precede the UN SDGs for 2030; as sustainable development policies and research have prioritized environmental and economic sustainability, giving less importance to social sustainability, with culture being frequently considered under the social sustainability dimension [5,31,32]. In fact, Cultural Heritage was also absent from both the MDGs and the first draft of SDGs [21].

Undoubtedly, the SDGs enshrine a conceptual shift in thinking beyond economic growth and imagining an inclusive, peaceful, and sustainable future. However, such bold vision and aspiration demand creative alternatives beyond the typical linear ones most WH cities have used in urban regeneration projects. Despite the efforts made by many platforms that are dedicated to including, integrating, and localizing culture among the SDGs (e.g., culture 21 committee of UCLG, 2018; CIVVIH/ICOMOS, 2020; ICOMOS-SDGWG 2020; and others), the potential to relate culture to the SDGs operationally appears to remain untapped in national and local strategies. For example, countries can adopt the SDGs. However, their implementation is not necessarily integrated within the local policies and strategies, and this is clear from reviewing the progress in achieving the SDGs within the Voluntary National Reports (VNRs) [33]. This impacts the protection of the OUV of a World Heritage site, especially when this is based on the intangible heritage that can only be protected through social and cultural sustainability and the well-being of the local communities carrying that heritage. The literature has also highlighted the many challenges in attaining adequate data and developing systematic methodologies to measure the progress of the SDGs on cultural heritage [34]. Moreover, the lack of correlation between the goals and their affiliated targets is another important aspect to address, with many vaguely defined targets and indicators. Consequently, when reviewing the progress reports written in 2016, 2017, 2018, and 2019, respectively [7], Target 11.4 or the progress of its indicator was not mentioned. The best example that illustrates the problem is the only indicator for Target 11.4, which is as follows:

“11.4.1. Total expenditure (public and private) per capita spent on the preservation, protection and conservation of all cultural and natural heritage by type of heritage (cultural, natural, mixed and World Heritage Centre designation), level of government (national, regional and local/municipal), type of expenditure (operating expenditure/investment) and type of private funding (donations in kind, private non-profit sector, and sponsorship)”[6], p. 24.

Interestingly, we still mark our progress in heritage preservation by the amount of funding spent on culture per capita. The preservation of tangible and intangible heritage can be measured by stakeholders’ participation, public awareness levels, integrity and authenticity, managerial system, continuity of intangible heritage, quality rehabilitation, reuse of heritage buildings, job opportunities, etc.

Global and local partnerships are also extremely relevant when mentioning the UNESCO WHL; hence, they can be found in Target 17.16, “Enhance the Global Partnership”; and Target 17.17, “Encourage and promote effective public, public-private and civil society partnerships”. However, similar to Target 11.4, which was mentioned earlier, the partnership with civil society within Target 17.17 is measured by the “Amount in United States dollars committed to public-private partnerships for infrastructure”. Heritage and local partnerships can be measured by their community’s performativity, livability, and diversity, including aspects such as the percentages of the local population engaged and the type and frequency of such partnerships. Limiting all those indicators to “Total expenditure” or “US dollars” is problematic. Furthermore, the notion that “there is not yet a UN definition on this indicator” appears in many indicators, opening another platform for discussion [6], p. 24.

Another case is in SDG 8. Although Target 8.1, “Sustainable Economic growth”; Target 8.3, “Promote policies to support job creation and growing enterprises”; and Target 8.9, “Promote beneficial and sustainable tourism”, are relevant to heritage-led urban regeneration, the indicators for these targets rely on the Gross Domestic Product, a monetary value abbreviated as GDP [6], p. 21. There was no mention of community involvement in the decision-making processes; no measure of public awareness of sustainable tourism; and no mention of the level of interaction with cultural knowledge, skills, and training programs [35]. Cultural and innovative sectors can be integrated into tourism strategies, active participation in cultural life, and the safeguarding of tangible and intangible cultural heritage, core components of human and sustainable development [35]. They have the potential to create inclusive, sustainable, and fair employment, provided that the appropriate labor conditions are met in accordance with international human rights. Including these in measuring the impact on future social and cultural sustainability is extremely critical, particularly in WH cities, where tangible and/or intangible heritage was/were found to be irreplaceable for all human beings. Social and cultural sustainability are important for the local community’s well-being, as they carry intangible heritage and sustain the tangible. The WH city of As-Salt is used as a case study in the next section to illustrate how problematic it is to use the relevant SDGs targets to measure the sustainability of heritage-led urban regeneration in the city.

4. The Case of As-Salt City in Jordan, as Recently Inscribed in 2021

After two unsuccessful attempts by local and international NGOs [36,37] to nominate the city of As-Salt in Jordan for the WH list in 1993 and 2004 [36,37], the Municipality of As-Salt led the latest two attempts in 2016 and 2020, respectively. In 2016, a nomination file was submitted under the title “As-Salt Eclectic Architecture (1865–1925) Origins and Evolution of an Architectural Language in the Levant” [38], with seven volumes of supportive documents. This nomination file focused on the tangible heritage of the city. A “serial property” of 22 buildings scattered around As-Salt’s historic city center, representing the city’s outstanding universal value under Criteria (ii) and (iii). A “unique architectural language” is regarded as considerable evidence of the flow of knowledge within the Ottoman Empire [38], p. 78. Once that file was deferred, another WH nomination file was submitted in 2020 under “As-Salt: The Place of Tolerance and Urban Hospitality” [39], p. 1. The focus of the OUV shifted to the city’s intangible values (i.e., the religious harmony of Muslims and Christians and the urban hospitability) [39]. This nomination was under the “site” category and Criteria (ii) and (iii) and has led to the successful inscription of the city on the WHL in 2021 [28]. The following section focuses on the last two attempts led by the local municipality.

4.1. Heritage-Led Urban Regeneration in As-Salt City

Since 2014, while the inscription status has not yet been confirmed, As-Salt has already started following the footsteps of other WH cities in the region. The chain of events leading to the inscription has triggered an increasing interest from the public and private sectors at national and international levels, who saw touristic opportunities for funding and investment in the city. This was translated into a proliferation of a series of urban development projects scattered around the city center and initiated without developing a clear master plan [36]. It has also triggered urban regeneration projects that focused on beautifying the city’s urban fabric and improving the tourism infrastructure [9]. These included forced eviction, acquisition, and demolition of more than 15 multi-floor buildings in the Oqbe bin Nafe project in the heart of the city heritage center. The occupants and the tenants of those buildings were forced to move out of the apartment buildings [40,41]. Traders from the shops on the ground floor of the demolished buildings were forced to relocate their businesses. Two schools were evacuated and had to move from the city center to the periphery. While this project has been on the agenda since 2007 [36], the kick-off of the actual implementation was in 2014, just after the roadmap of As-Salt nomination was announced. This is because the project included the tourism infrastructure (a visiting center, souvenir shops, public facilities, and restaurants) needed for the WH nomination file [38]. Despite many protests from the occupants of those buildings, in preparation for the WH nomination attempt in 2014, the city court ruled in favor of the municipality for the compulsory acquisition of and demolition of all of the existing buildings in an urban area estimated as 13,900 square meters known as the Oqbe triangle [41]. This allowed the municipality to resume its plans and accelerate the construction process of the newly designed urban regeneration project [36].

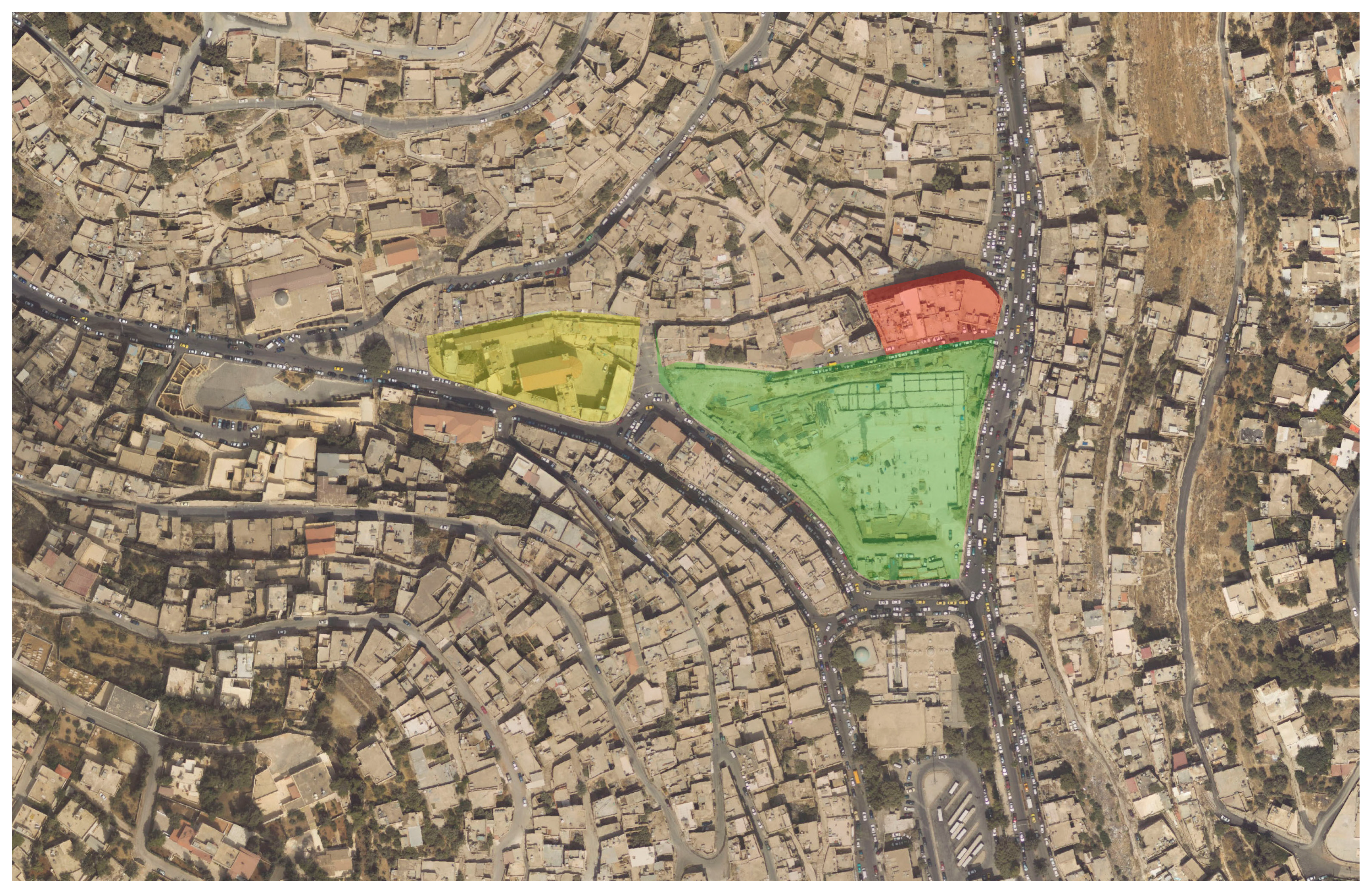

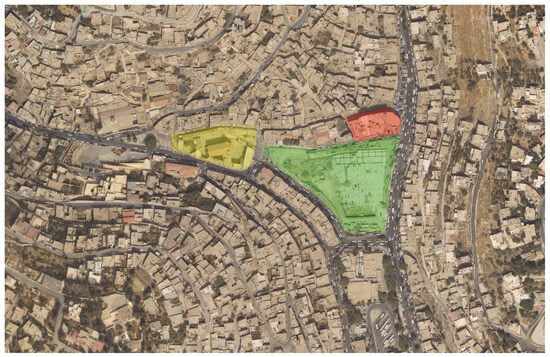

After the deferral in 2017 of the WH nomination file (focusing on the tangible heritage of the golden era), another WH nomination file was submitted in 2020 (focusing on the intangible heritage of As-Salt (i.e., the urban hospitality and religious tolerance among Muslims and Christians)). This has also triggered urban regeneration projects focusing on beautifying the city’s urban fabric and improving the tourism infrastructure. The Oqbe bin Nafe project was followed by a second project phase (Oqbe bin Nafe Phase 2) and a third phase (Oqbe bin Nafe Phase 3) in 2019 and 2020, respectively. In Phase 2, SGM decided to extend the project to include several multi-story buildings (5–7 floors) adjacent to the site, demolish them, and design an extension of public plazas with sitting areas and one-story shops [38,41]. Phase 3 included the SGM acquiring the Latin school surrounding the Latin church at the project’s rear to demolish it, widen the open spaces, and beautify them [28]. See Figure 2 below for the three phases of the project.

Figure 2.

Oqbe bin Nafe’s project Phase 1 is highlighted in green on an aerial photo taken in 2014, Phase 2 is highlighted in red, and Phase 3 is highlighted in yellow Source: creation of the first author.

Other projects in the city center included changing the local transportation hub to the outskirts of the historic center, changing the bus routes, and pedestrianizing a few streets in the city center [36]. The municipality also prohibited polluting activities such as chicken butchery and unified the street signage in the local markets, impacting many local livelihoods. Private initiatives have also increased to create tourism-oriented attractions, such as rehabilitating heritage buildings into cafés and restaurants. The newly established cafés and restaurants initiated the site’s most immense publicity. They publicize the views, nostalgic experience, and the food of As-Salt to attract visitors. At the time, these were randomly scattered around Al-Khader Street, Midan Street, Hammam Street, and Jada’a Mountain. These include Gerbal restaurant, Eskandarane café, Beit Aziz Bed and Breakfast, Al Aktham café, and many others.

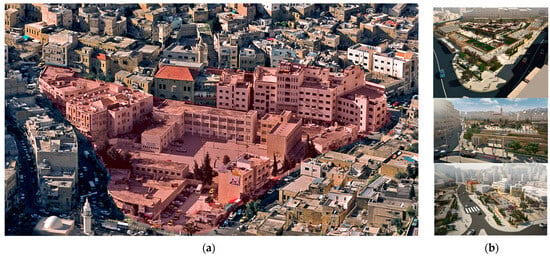

4.2. As-Salt Urban Regeneration after the Successful Inscription on the WHL

Nearly eight months after the successful inscription of the city on the WHL in July 2021, and even though the successful WH nomination file was based on intangible cultural heritage, such as urban hospitality and religious tolerance, the same pattern of regeneration that started before the inscription on the WHL continued [39]. Immediately after the inscription, more urban-regeneration projects were planned, such as restoring a few monumental heritage buildings and introducing a new multi-story car park which replaced the inner-city bus terminal [9]. However, the implementation speed of the new project slowed after the inscription was granted. Since the successful inscription, only a few small-scale projects have been implemented to beautify the city’s townscape. In fact, many projects lost momentum, such as Phase 1 of the Oqbe bin Nafe project, which started showing signs of failure, as the buildings completed in the early phase were left empty and closed due to their high rents that were not affordable for the existing local community. This was indeed discussed between five traders (who used to have shops on the site before the regeneration project) and the municipality, which offered them the opportunity to rent the shops in the new project. However, they refused to resume their agreement with the municipality due to the high rent and operation expenses. They were also discouraged by the design of the shops, which have their main facade and shop window into the site instead of outward into the peripheral lively streets with high footfall [28]. Thus, they preferred to take their business elsewhere. This illustrates how the project’s design disregarded the local community’s lifestyles and trading preferences and followed a top-down approach to decision-making, which ended up with a failed project still closed in 2024!

Despite the failure in Phase 1 of Oqbe bin Nafe project, Phase 2 started even before securing the project’s financial needs, and many existing buildings were forcibly evicted and demolished. The municipality explained that the responsible government’s financial support for all the development projects in the city center stopped in 2019 [42]. Since then, the projects have relied almost entirely on foreign aid and grants, which were not guaranteed, leading to a shortage in funding for the project. This has also been exacerbated by the municipality spending funds on compensations for the displaced local community, leading to the expenditure of the budget allocated to the projects in 2014 [9]. Therefore, the municipality of As-Salt eventually decided to seize Phase 2 of the project. Instead of starting the second phase of the project, the municipality has been clearing the site of Phase 2 to be used as a temporary parking space as requested by the local community. Therefore, there is a lack of sound site and project management. A feasible financial plan should have been established to take place within a feasible timeframe before initiating these mega-projects. For two years (2020–2022), the site was cleared from its existing buildings and remained vacant in the city’s heritage heart. It continues to be used as a temporary car park facility and has attracted informal stalls, perceived by many as a visual and environmental hazard [42].

Regarding Phase 3 of the project, the plans included acquiring the Latin school buildings, evacuating the school and its students to the suburbs, and demolishing the buildings around the Latin church to design a landscape area and expose the church. This phase has yet to be planned, with a high possibility of cancellation. Nevertheless, the buildings were acquired in 2019 and remain empty and abandoned in 2024. This also shows that decisions are made randomly without a careful and realistic overall master plan. They acquired the buildings and pushed the school out of the city center without having the project fully planned or securing the funding it needed. In fact, the unit responsible for managing the heritage center was closed and had no replacement [43]. In the three phases, Oqbe bin Nafe’s project included the demolition of primary and secondary schools, bank branches, around 20 apartment buildings (five or six floors each), local shops, NGOs, and offices [36,40]; see Figure 3 below. These were important for the local community to carry out their everyday activities and were part of the local community’s collective memory. Demolishing them decreased the local footfall within the market area and has economically affected the other shops around them, especially outside the tourism season.

Figure 3.

(a) Oqbe bin Nafe Project in As-Salt City Center highlighted by the author on an aerial photo that was taken in 2007; demolished buildings are highlighted in red. (b) The new project design [36].

In addition, with a guaranteed status on the UNESCO WHL, more investors found opportunities in the tourism sector. They started purchasing or renting heritage buildings around the historic center. Most of these rehabilitation projects mainly host activities that focus on activities that promote the intangible heritage of As-Salt, which opened in 2021–2022. Examples of these projects include the Balqawi wedding experience, Jordan heritage restaurant, and Al-Khader bazaar, among many more. The locations of these seem to be clustering around JICA 2012 tourism trails guided by local entrepreneurs. These are the only active trails in the city center with allocated local guides to benefit from the footfall of tourists.

5. As-Salt Urban Regeneration Practices and the SDGs

Linking this case study back to the SDGs, the case of As-Salt shows how relevant the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are in measuring the sustainability of the urban regeneration trajectories in World Heritage Cities. These are demonstrated within each of the relevant SDGs to heritage-led urban regeneration as follows:

SDG 11, “Sustainable cities and communities: Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable”.

The best example to highlight the problematic targets within SDG 11 is Oqbe bin Nafe project Phase 2, mentioned earlier. Millions of dollars were put into a scheme that relied on the demolish–build–demolish–build pattern [42]. These funds could have incentivized the community to invest in the center or build a more durable car park at the city’s edges. Therefore, if we are measuring the expenditure spent on these urban regeneration practices since 2014, then the Oqbe bin Nafe project would have successfully achieved Target 11.4 (protect the world’s cultural and natural heritage). Acquiring these buildings, compensating their owners, demolishing them, and starting high-end and large-scale projects must have cost millions of U.S. dollars; see Figure 4 below. However, the result was not sustainable at all; the displacement of the local community is a significant cause of losing this intangible heritage. Due to the lack of social and cultural aspects in this target or its indicator, the shifting of the commercial center to the periphery of the city, the disappearance of the intangible heritage, and many others are dismissible. Therefore, this is not an adequate measure of Sustainable Development, as it favors monetary measurements and neglects local social and cultural sustainability values.

Figure 4.

The timeline for implementing the Oqbe bin Nafe project’s Phase 2. Source: creation of the first author.

Furthermore, immediately after the WH inscription, the municipality experienced financial constraints, which led to the closure of the ASCDP unit in charge of the heritage city center, as it was not able to pay the salaries of the employees and the ongoing projects [42,43]. In fact, all phases of the Oqbe bin Nafe project lost momentum due to financial constraints [28]. Therefore, there was clearly an issue with the management of the city and its financial resources.

Authorities in the city continuously changed conservation policies to follow UNESCO’s recommendations without considering the local community’s needs [42]. Furthermore, the lack of community involvement and participation in the regeneration plans for the city of As-Salt does not resonate with Target 11. (strong national and regional development planning) and Target 11.3 (inclusive and sustainable urbanization). The lack of a master plan, with random projects scattered around the city center and different agendas of various stakeholders involved is proof of the lack of planning coordination at local, regional, and national levels. In addition, the contradictory priorities of different stakeholders and the confusion of their roles are also against Target 11. In fact, the indicators for Target 11.3 are “11.3.1 Ratio of land consumption rate to population growth rate” and “11.3.2 Proportion of cities with a direct participation structure of civil society in urban planning and management that operate regularly and democratically” [44].

Target 11.3 could be the most relevant target to enhance inclusive and sustainable urbanization and capacity for participatory, integrated, and sustainable human settlement planning and management. However, it needs to clarify the terms of direct participation and the proportion of the civil structure involved in the participation. Therefore, these targets are problematic because they do not mention the awareness level and the consensus between different stakeholders in their understanding of what constitutes the tangible and intangible heritage of the city.

SDG 8, “Promote sustained, inclusive, and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment, and decent work for all”.

In the city of As-Salt, urban regeneration projects such as the Oqbe bin Nafe project and the development of the hospitality sector have surely enhanced the tourism infrastructure and the city’s visual appearance and exposed the heritage of yellow limestone buildings. These tourism-led projects may generate income and support the creation of catering jobs, which contribute directly to the SDG targets (8.1, 8.3, and 8.9). However, the forced eviction, the demolition of buildings, and the shifting of the local community commercial hub from its original location in the city center to the periphery create other economic problems, such as depriving the center of its local community members who previously needed to visit the city center for everyday activities. This impacts the city center’s footfall, particularly for the locals visiting the commercial markets, schools, banks, and government buildings in everyday life. Furthermore, the recent COVID-19 crisis has also opened the discussion around the risks associated with the over-reliance on tourism to economically sustain communities and heritage sites [45]. The COVID-19 pandemic has stopped all types of international tourism, causing a massive blow to the sector. Amidst international travel restrictions, border closures, and physical-distancing measures, countries have been forced to impose widespread closures of heritage sites, cultural venues, festivals, and museums, some of which may never reopen. This directly impacted the local communities that rely on tourism income [46]. Therefore, to sustain the livelihood of the local communities living in heritage centers, we must acknowledge that the communities are the carriers of the intangible heritage and the keepers of the tangible heritage. Furthermore, the lack of monitoring of the living costs in the city center after the WH inscription in As-Salt raised property and retail prices.

Regarding Target 8.3, a local community questionnaire, conducted in March 2022 by the main author in As-Salt, concluded that 30% of the respondents (n = 55 respondents) who were aware of the City Core Special Regulations (CCSRs) governing the heritage city center disagreed with them or could not access them [9]. That was justified, as the restoration and renovation guidelines within the laws protecting the city center were overwhelming and required high-end restoration techniques that were extremely expensive and required professional human power. These laws were not accompanied by any financial and technical support or incentive programs, such as tax reductions, grants, and funds to support the rehabilitation of heritage buildings. The only indicator for that target is as follows: “Proportion of informal employment in total employment, by sector and sex” [44]. However, this does not cover promoting policies that encourage local investments. It is extremely important to include these incentives and support as an indicator of achieving that target. Using the same approach for SDG 8.1, there is no mention of community involvement in the decision-making processes; no measure of public awareness of sustainable tourism; and no level of interaction with cultural knowledge, skills, and capacity-building programs.

It is essential to mention that cultural and innovative sectors can be integrated into tourism strategies, active participation in cultural life, and safeguarding tangible and intangible cultural heritages, which are core components of human and sustainable development [35]. The Ministry of Tourism in As-Salt revealed that internal tourism has thrived in the last few years, with around a 5% increase from 2019 and a 36% increase from 2020 to 2021, and is still rising, with 123,000 tourists recorded in 2022, based on MoTA records. The year 2020 was a fall due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The number of foreign workers in the hospitality sector has increased by 30%, as well as in souvenir and craft shops. However, there were never any studies, statistics, surveys, or guidelines mapping the engagement of the local communities within those. These are all aspects that can also promote an area for inclusive, sustainable, and fair employment regarding the appropriate labor conditions and ensure the well-being of the local communities. Engagement with local communities is paramount for developing sustainable strategies for conserving and managing heritage settings. A lack of stakeholder representation can damage trust and relationships, and decision-making can overlook the concerns of local communities.

SDG 17, “Revitalize the global partnership for sustainable development”.

Excluding the local community from the decision-making processes in the city highly impacts the city’s management and directly impacts the partnership notion of SDG 17. The lack of partnership between the different stakeholders in the city and the confusing roles of the authorities in the city also add to the dilemma. The mechanisms for receiving funding in the city are usually articulated to the purpose of the sponsor’s agenda and have many limitations and restrictions [9]. This means proposing random projects that meet the sponsor’s agenda to accommodate grant calls and proposals. It is crucial to have a set of goals and objectives as part of an overall master plan with some guidelines to manage the process of receiving financial aid and grants. The closure in August 2022 of the As-Salt City Developing Projects’ unit ASCDP (which was managing the heritage center) soon after the successful inscription of the site on the WHL has left a critical administrative gap at a time when the city should attract grants and funds to start implementing the management and conservation plans associated for ICH Outstanding Universal Value. This has been further exacerbated by removing the heritage property manager from her post as the head of the Municipality Heritage Unit, leading to no access to the As-Salt heritage database. Since then, there has been no specific unit/office in As-Salt Municipality to receive applications for heritage conservation and management grants or negotiate the terms of grants [43]. The continuity of teams involved in the project is crucial to financial sustainability and resilience for the implementation of an agreed management plan.

Considering the current pattern of urban development and urban governance in As-Salt, it is likely that the city would also receive a negative UNESCO’s first monitoring report in three years. UNESCO would highlight the decline in physical conditions and managerial changes and might grant financial support to restore some monumental buildings. In the long and medium term, there is a possibility of a decline in UNESCO’s monitoring role in the city [9]. Their involvement would potentially be limited to monitoring reports and some financial assistance (only if the application of the state party is approved). These trajectories are not sustainable based on the UN SDGs. Inconsistent communication between UNESCO and the state party and the state party with other city stakeholders is jeopardizing meeting SDG Target 17.16, related to enhancing the global partnership for sustainable development, and Target 17.17, related to encouraging effective partnerships. Therefore, the development of more inclusive partnerships with local communities and enhancing the governance structure and operations of the municipality must be addressed locally as a matter of urgency to ensure that social and cultural sustainability are carefully considered for the resilience of both tangible and intangible heritage. There is also an urgent need for multi-scalar collaboration and partnership between local, regional, national and global institutions for clearly integrated joint strategies that take social and cultural sustainability as a core priority, meet the SDGs and provide alternative sustainable heritage-led urban regeneration.

Finally, the last two targets, Target 17.18, “Enhance availability of reliable data”, and Target 17.19, “Further develop measurements of progress”, can help bring culture and heritage to the table to address these shortcomings.

Despite all the mentioned shortcomings, the SDGs and the 2030 agenda are to be taken as the main reference in this paper as there is already a policy document in place for the “Integration of a Sustainable Development Perspective into the Processes of the World Heritage Convention” [47]. This document was adopted in 2015 by the General Assembly of States parties to the World Heritage Convention at its 20th session. It recognized the World Heritage Convention as integral to UNESCO’s overarching mandate to ensure coherence with the UN Sustainable Development Goals. This integration was found important by UNESCO as it enables state parties of WH sites to play a role in implementing SDGs. It also sets the standards for WH cities to act with social responsibility as innovative models of sustainable development [47]. Although this policy was introduced nine years ago, in 2015, it has unfortunately not been sufficiently activated and used. However, it justifies the focus of this paper, which is on integrating the SDGs within the framework of WH guidance. To feed into the sustainable development framework globally, there is a great need to address cultural and social sustainability within the overall framework of the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda at the national level. This requires adjusting the governance practices within the management of World Heritage Cities to eliminate embedded obstacles to implementing social and cultural sustainability.

To reach a more inclusive and sustainable outcome and overcome the SDGs’ shortcomings, there is a need to investigate where social and cultural sustainability in previous UN initiatives correlate, overlap, and/or complement the UN 2030 SDGs in focus. The next section introduces two earlier initiatives: the Historical Urban Landscape Recommendations (HUL) 2011 and its subsequent New Urban Agenda (NUA) 2016. These two initiatives were related to heritage-led urban regeneration and community-led approaches for the holistic preservation of an urban setting and could complement the SDGs to overcome its current shortcomings.

6. Complementary Initiatives from the Corpus of the UN for Sustainable Development

6.1. The Historic Urban Landscape Recommendations (HUL) in 2011

HUL recommendation serves as both a definition and an approach. As a definition, it broadens our understanding of the historic environment and identifies the complex elements and layers that make our cities distinctive with a sense of place and identity [48]. As an approach, it establishes the basis for integrating urban conservation within an overall sustainable development framework by applying a range of traditional and innovative tools adapted to local contexts. This holistic and interdisciplinary approach goes beyond the notion of the historic center to include the broader urban context and its geographical setting. It acknowledges cities as living heritage and community-led endeavors that challenge urban planning and development systems [49]. HUL was meant to combine and complement previous European and international doctrines and charters rather than replace them. It is an additional tool to integrate policies and practices of conservation of the built environment into the broader goals of sustainable urban development [7]. The aim is to emphasize the engagement and collaboration with communities associated with the landscape and to grasp the different values and heritage significance that could support a cross-cultural dialogue between the various stakeholders, positioning the increasing complexity around decisions on what attributes and values to protect for future generations, especially in a constantly changing environment.

The recommendation provides a more global vision and gives special attention to the communities inhabiting historic towns or centers. This approach is presented in a document with 30 articles under six main themes to facilitate the adoption and implementation of this new instrument. In theory, the HUL is an ideal fit for involving the local community in decision-making processes within WH cities. It also considers all the site’s values, alongside the OUV. Implementing the HUL guidelines would encourage a more sustainable and positive outcome and include the voices of the communities in the decision-making processes. However, in practice and until 2023, ten years have passed since the adoption of the HUL, and the academic discussion stands today in operationalizing this approach and adapting its theoretical and conceptual framework to local contexts. The implementation and the intellectual debate do not yet cover the entire spectrum provided by the HUL definition and guidelines [50]. This is due to the challenges facing the application of the HUL and the value-based approach, which revolve around heritage being a complex social construct mutable and contested in character [19]. Heritage can be perceived and understood differently, depending on the lens used. The interpretation of this lens can vary depending on the observer’s agenda, personal history, ideologies, etc. [19,20].

Furthermore, given the interdisciplinary, all-inclusive, value-based character of the HUL, bringing all of these characteristics together and assembling its components can be challenging, as well as addressing the values of cultural heritage in explicit and unambiguous terms. Not fully contextualized and localized, the discussion about value-led initiatives remains generic [51]. As such, the accountability of a value-based approach is compromised, especially in contexts that tend to be dominated by groups with the most political power; it remains critical if it fails to assure equity and stakeholder involvement to avoid the dominance of values that represent groups with the most political power [52]. These issues are maximized in WH cities, as the local and international politics are more complicated, especially when the roles of different stakeholders are unclear.

Thus, although the HUL approach offers a genuine advantage in managing heritage in urban areas, because of this conceptual confusion, it does not yet represent a significant advance toward the integrated management of tangible and intangible heritage without the necessary clarifications. Unfortunately, this issue started well before the HUL. UNESCO started placing more emphasis on intangible heritage in 2003, when a new Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity was adopted by UNESCO’s General Assembly. However, although UNESCO’s literature on the intangible cultural heritage (ICH) program reflects a utopian emphasis that is filled with empowerment phrases, such as “community-based”, “grassroots level”, “vessels”, and “capacity building” [53], it resulted in a counter effect. The ICH discourse treats those who engage in each practice as anonymous “bearers” who carry and pass on a practice—adding their personal touches along the way. The heritage practice becomes the focus of concern, and the people who engage in that practice become of secondary importance: interchangeable “vessels” whose life circumstances or personal wishes are essential to the discussion only as much as they affect the continuation of the heritage practice. In turn, anonymizing the heritage practitioner can have undesirable effects [54]. Therefore, the discourse surrounding the ICH safeguarding paradigm is portrayed as a process that gives voice to communities and recognition to practices otherwise ignored, presenting it as a tool that allows these communities to resist homogenizing globalization. It is a legacy that gives a character and an identity to the community that represents them and can be inherited by future generations. This paradigm can do much the opposite and has the potential to disempower and silence some, while inserting a new heritage middle management who speaks on their behalf [54]. This imbalance of agency and influence does not necessarily result from short-sightedness, lack of awareness, or incompetency on the part of those implementing a heritage program. Instead, it is from built-in aspects within urban governance and how intangible heritage safeguarding programs are constructed and implemented. This is mainly due to requiring experts with skills and levels of access to establish what constitutes the intangible heritage of a community that many of those who practice the cultural heritage in question do not possess. In practice—if not always—these people within the communities become the objects of heritage safeguarding programs as practitioners who passively “bear” and “pass on” that heritage rather than the decision-makers who shape and continuously recreate it as part of their daily lives [49]. This approach has unsustainable consequences for urban regeneration scenarios in WH cities. Therefore, it was unsurprising that UNESCO needed to include more Sustainable Development initiatives afterward, such as the HUL. There was a need for more protection measures and management guidance beyond that offered by the WHC (World Heritage Convention). Although praised by academics and experts, it left more questions than answers.

However, the lack of attention to intangible heritage as practice can mean that implementing the HUL recommendations does not go beyond a focus on conserving the authenticity and integrity of the built environment with some community flavor, which has turned out to be a significant issue in WH cities. A truly integrated approach would focus on managing historic urban landscape values and on the local communities and safeguarding their practices. Safeguarding intangible heritage practices might be included in management planning where they are located in specific places in the city or are more diffuse, and whether they attest to the authenticity of this built fabric. Resources would be committed to the safeguarding of cultural practice. A better understanding of the concept of intangible heritage and its use in different UNESCO instruments can facilitate discussion within UNESCO and between experts working on the World Heritage and Intangible Heritage Conventions [49]. This understanding should be established by the people caring for and practicing this intangible heritage. As is, the HUL cannot on its own be a reference to guide WH city’s sustainable practices; it is concluded that, due to the many challenges, it must be complemented, contextualized, and applied from an operational level. The HUL recommendations alone can be challenging regarding the national/international networking, measurement, and monitoring aspects, with no clear understanding of the values and priorities within the site.

6.2. The New Urban Agenda NUA: UN-Habitat III in 2016

One year after initiating the Sustainable Development Goals (2016), the New Urban Agenda (NUA) was adopted at the United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development (Habitat III) in Quito, Ecuador, and was endorsed later that same year [55]. The NUA represents a shared vision for a better and more sustainable future, one in which all people have equal rights and access to the benefits and opportunities that cities can offer and in which the international communities reconsider the urban systems and physical form of our urban spaces to achieve this. The agenda sets a new global standard for sustainable urban development and will help us rethink how we “plan, manage and live” in cities. It is a roadmap for building cities that can serve as engines of prosperity and centers of cultural and social well-being while protecting the environment [8]. This NUA document published on the UN’s official website contains vital concepts and corresponding paragraph numbers. These concepts represent 175 commitments from the UN, the national governments, and local authorities to implement the agenda, including technical and financial partnerships and assistance from the international community [8]. Although the agenda’s development resulted from a separate timeline of the UN-Habitat process, the NUA was intricately connected to the Sustainable Development Goals. It is seen as the delivery vehicle for the SDGs in urban settlements.

“Although, for political reasons, there is no formal link between the NUA and the SDGs, there is a wide consensus that the SDGs, and especially the urban goal and the urban elements of the other goals, should constitute the de facto monitoring and evaluation framework for the New Urban Agenda”[56], p. 1.

The agenda guides the achievement of sustainable development goals and provides the underpinning for actions to address urbanism and climate change [8]. Therefore, one of the main aspects covered by this agenda is deciding how relevant sustainable development goals will be supported through sustainable urbanization.

NUA is the final UN initiative highly related to heritage-led urban regeneration discussed in this paper. Many aspects still need to be addressed within each of the three UN initiatives. Therefore, this paper argues for an approach that integrates some of the commitments made in the New Urban Agenda within the Sustainable Development Goals and articles from the value-based HUL recommendations. The next section examines synergies, correlations, and complementarity between the three initiatives for the development of a more comprehensive set of goals that promote heritage-led urban regeneration that is socially and culturally sustainable for cities acquiring UNESCO WH status.

7. Results: An Integrated Approach for Sustainable Development under the Umbrella of the 2030 SDGs

UN platforms are a good starting point for initiating more socially and culturally sustainable approaches toward heritage-led urban regeneration. However, this paper has identified many shortcomings in addressing social and cultural sustainability, as well as environmental and economic sustainability. There is a separation between the different UN and UNESCO initiatives, and this creates a potential conflict in the heritage preservation for all humankind offered by UNESCO WHL and the promotion of Sustainable Development, also established by the United Nations (UN). While all mentioned initiatives, including the WH convention, are oriented toward protecting cultural heritage and improving the lifestyle of local communities, adopting WH listing and the different criteria under the UN umbrellas might lead to a potential conflict of interest in the same urban site.

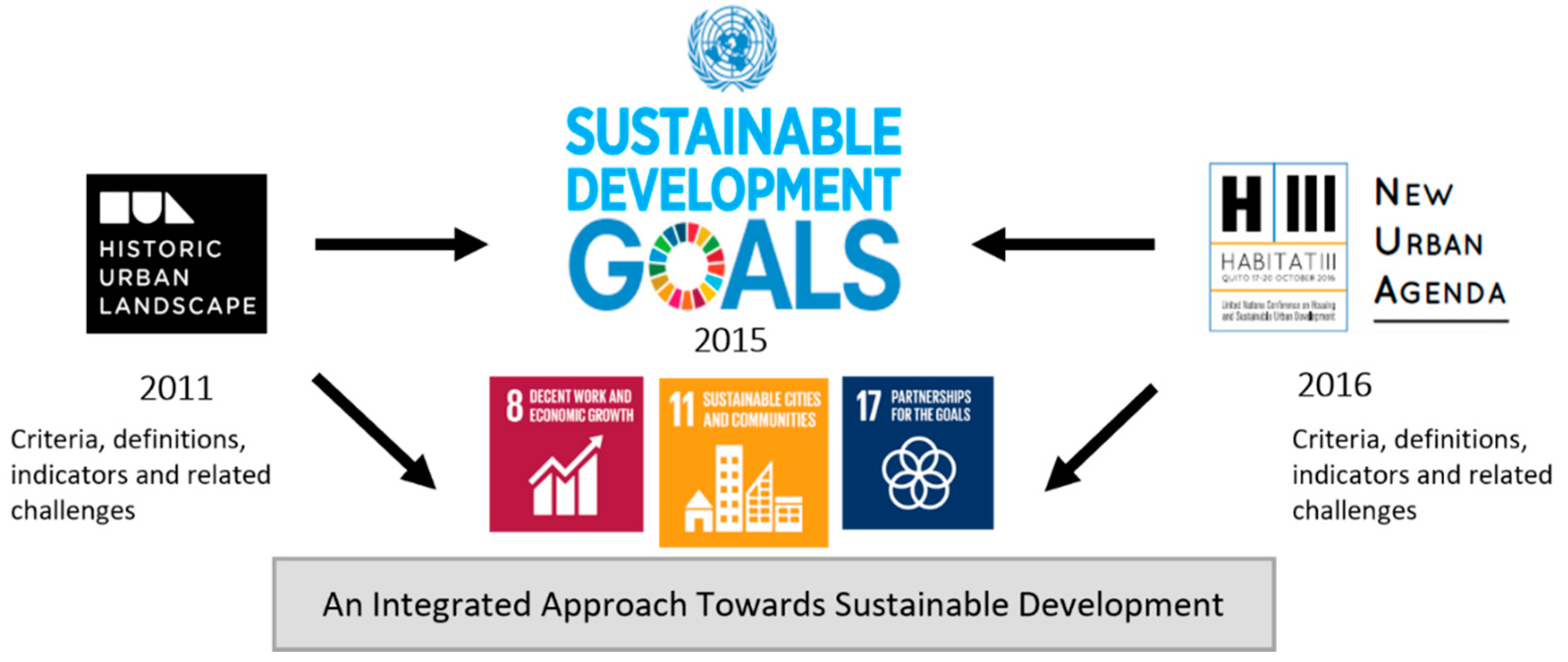

Furthermore, there is an apparent difficulty in translating those initiatives into local actions. There is a need to incorporate and complement some of those initiatives for a more inclusive framework that covers all pillars of sustainability and can be implemented locally. It is necessary to address those shortcomings of the SDGs before using them as a reference and guiding framework, especially in cities where culture and heritage are integrated into the local communities’ lifestyles and livelihoods. Therefore, this paper also suggests an integrated approach that would allow for a more comprehensive framework toward sustainable development. The proposed relationship between the three platforms is illustrated in Figure 5, and the roles of each are listed below.

Figure 5.

An integrated approach toward Sustainable Development from the three initiatives (SDGs, HUL, and NUA) Source: creation of the first author.

- The Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) recommendations can act as a first step toward looking at urban heritage to be inclusive and understanding the site’s different layers. It goes beyond the notion of the historic center to include the broader urban context and its geographical setting. It also positions the increasing complexity around decisions on what attributes and values to protect for future generations in a constantly changing environment.

- The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the 2030 Agenda are current global movements signed by almost all the UN member states [44]. They cover areas not mentioned by the HUL and NUA, such as international networking or providing measurement and monitoring standards. The SDGs will be used as the widest umbrella in this paper for inclusive, sustainable development with input from the HUL and NUA.

- The New Urban Agenda (NUA) highlights a connection to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and provides guidance and a roadmap for achieving the goals, especially Goal 11, on sustainable cities and communities. It can serve as an engine of prosperity and a center of cultural and social well-being, while protecting the environment; it also underlines the linkages to urban renewal policies and strategies and provides the role of both the support of the UN and the role of countries in the urban regeneration processes.

To develop this integrated approach toward Sustainable Development, three phases are followed:

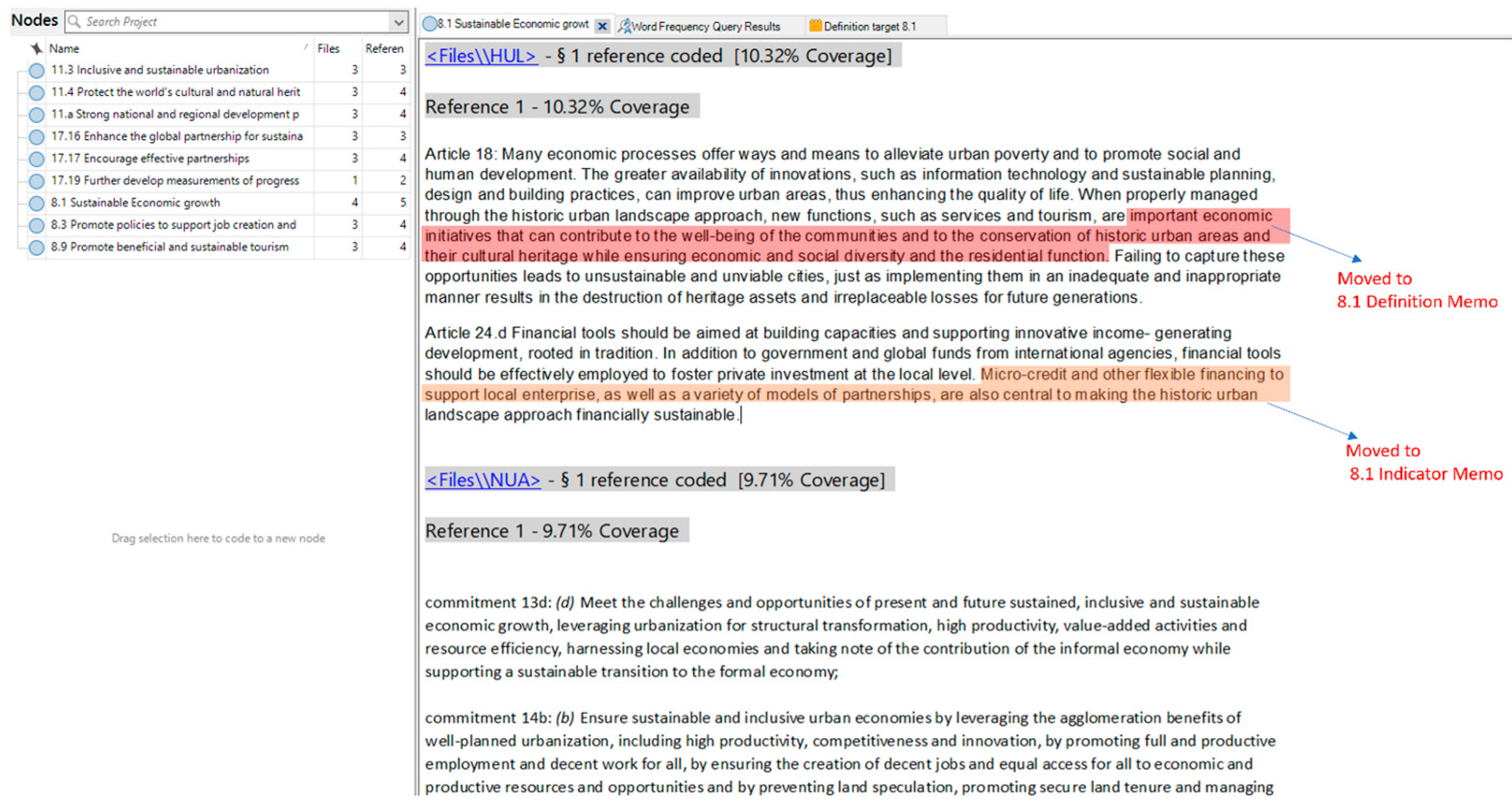

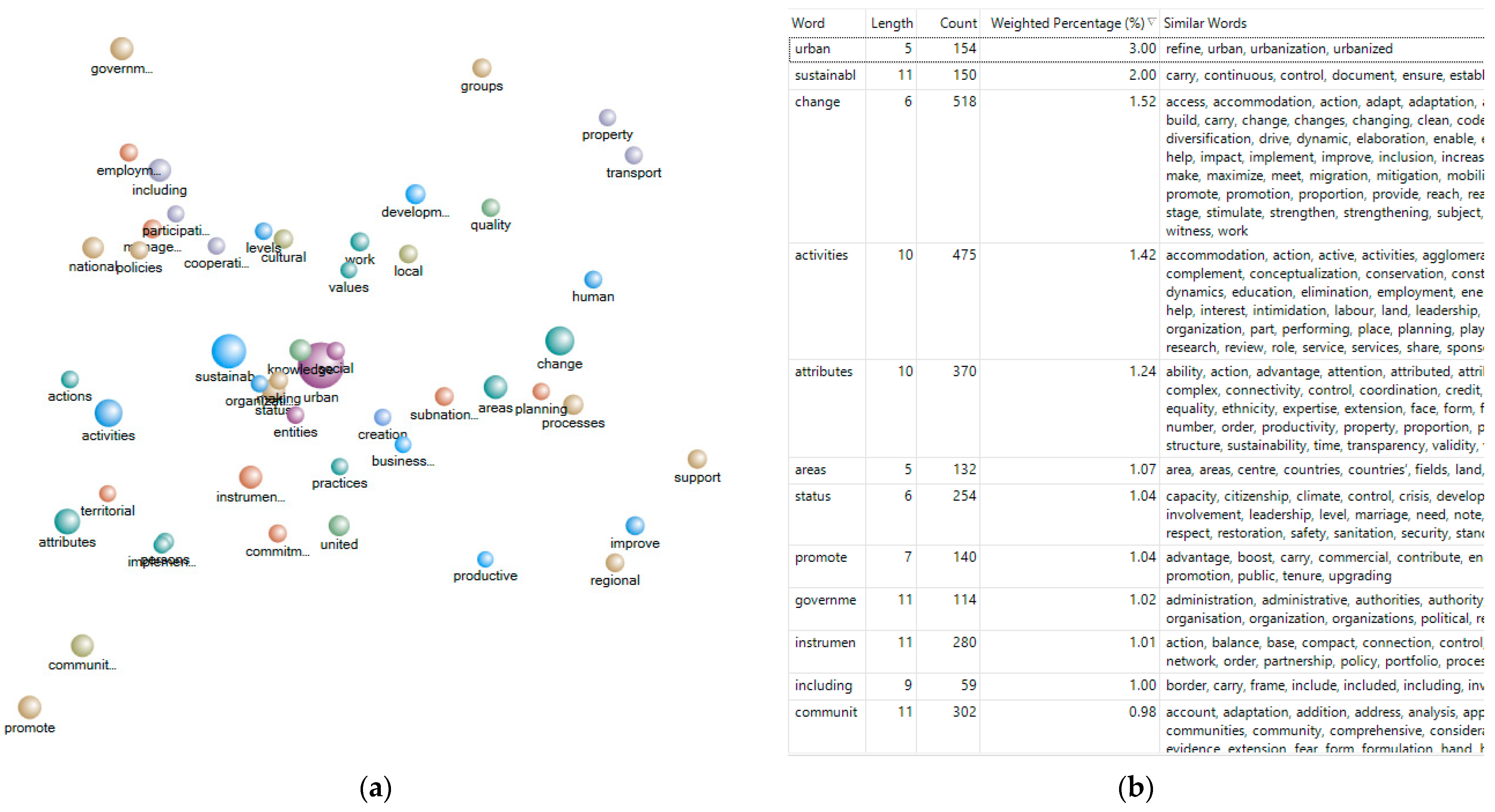

Phase 1: Positioning where the NUA and HUL overlap with the SDGs’ relevant target to heritage and culture. To do so, secondary data from the text of the published documents of the UN initiatives for sustainable development (commitments from the NUA and the articles from HUL and the SDGs targets and indicators) were analyzed using a critical content analysis. The data were entered into a qualitative analysis tool (NVivo) and categorized based on different nodes, each dedicated to an SDG target. For example, where information was found related to Target 8.1 (sustainable economic growth), it was categorized and moved to that node. Table 1 below illustrates how the contribution from each initiative is categorized under the most relevant SDGs, which are SDG 8 (8.1, 8.3, and 8.9), SDG 11 (11.3, 11.4, and 11. a), and SDG-17 (17.16, 17.17, 17.18, and 17.19).

Table 1.

The overlapping of the HUL recommendations and the NUA commitments with the related SDG targets Source: creation of the first author.

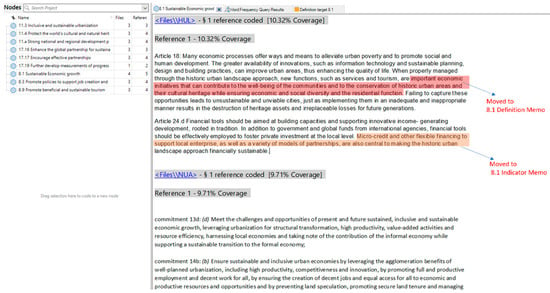

Phase 2: Once all the data are categorized into specified nodes for each target, this phase is dedicated to studying the correlations such as the coding of word frequency, areas of focus, overlapping and others. Within each node, the data is categorized again, whether they are more relevant as a definition or an indicator within “Memos”; one for the definition and one for the indicators. Using the same example of Target 8.1 (Sustainable Economic growth). Articles 18 and 24d from HUL and Commitments 13d, 14b, 43–45, 56, 60, 62, and 66 from NUA are carefully analyzed and categorized, as illustrated in Figure 6 below.

Figure 6.

Analyzing the secondary data from the three initiatives’ contents using NVivo. The figure shows how the data relevant to Target 8.1 were categorized as definitions and indicators, Source: creation of the first author.

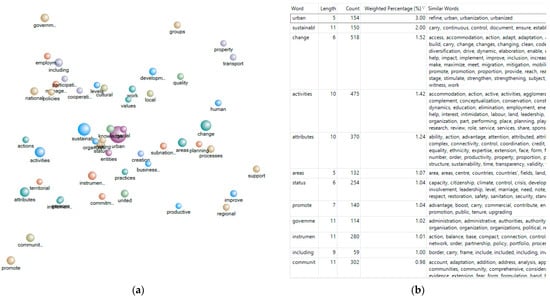

Phase 3: Data curation, once the analysis is completed for all relevant SDG targets, a refined definition for the targets and new indicators are created. The definition and the indicator of each goal were analyzed by studying the correlations among the combined data from the three UN initiatives and word-frequency analysis. Figure 7 below demonstrates how these were identified in the wider context they were used in. By doing this to all the relevant targets, the overlapping and areas of correlation would be identified to ease the development of a more comprehensive set of criteria covering all aspects of sustainability, including social and cultural sustainability.

Figure 7.

Studying correlations and word-frequency analysis that was performed in those two categories: (a) a figure that shows a correlation of the terms used in the initiatives; and (b) word-frequency analysis using NVivo.

- To further explain the process, the existing UN definition and indicator for that target are as follows:

- Target 11.4. Protect the world’s cultural and natural heritage: Strengthen efforts to protect and safeguard the world’s cultural and natural heritage. Indicator:

- 11.4.1:

- Total per capita expenditure on the preservation, protection, and conservation of all cultural and natural heritage, by source of funding (public and private), type of heritage (cultural and natural), and level of government (national, regional, and local/municipal).

- The proposed new definition and indicators after the data curation phase are as follows:

- Target 11.4. Protect the world’s cultural and natural heritage: Strengthen efforts to protect and safeguard the world’s cultural and natural heritage through identifying, conserving, and managing historic areas within their urban contexts. Recognize the different values attributed to heritage by various stakeholders and promote participatory urban management strategies. Indicators:

- 11.4.1.

- Number and quality of efforts to promote the innovative and sustainable reuse of architectural monuments and sites, and value creation through respectful restoration and adaptation.

- 11.4.2.

- Number of engaged Indigenous people and local communities in the promotion and dissemination of knowledge of tangible and intangible cultural heritage and protection of traditional expressions and languages, including using new technologies and techniques.

- 11.4.3.

- The increase in cultural promotion of museums, indigenous cultures, and languages, as well as traditional knowledge and the arts, highlights how culture plays a role in rehabilitating and revitalizing urban areas and strengthening social participation and the exercise of citizenship.

- 11.4.4.

- The level at which urban heritage, including its tangible and intangible components, constitutes a key resource in enhancing the livability of urban areas and fosters economic development and social cohesion in a changing global environment.

- 11.4.5.

- Number of initiatives that harness the potential of cultural heritage to enhance the identities, and sense of belonging to create job opportunities and sustainable livelihoods, stimulate dialogue across different communities, and encourage social inclusion, especially of the most vulnerable and marginalized.

The example presented above illustrates how the three UN initiatives can complement each other to more clearly redefine targets and indicators, particularly those relevant to heritage-led urban regeneration, as well as how they can be applied to all the SDGs’ targets to balance social and cultural sustainability, along with environmental and economic sustainability, and override the shortcomings of the SDGs. This suggestion is only a starting point in the discussion that could be employed for WH cities that resonate with the purpose of Sustainable Development promoted by the SDGs.

8. Discussion

This paper recognizes the World Heritage Convention as integral to UNESCO’s overarching mandate to ensure coherence with the UN Sustainable Development Goals [26]. Heritage can be measured by stakeholder participation, awareness level, integrity and authenticity, the managerial system, the continuity of intangible heritage or the quality rehabilitation processes, the reuse of heritage buildings, the provision of job opportunities, etc. Thus, a more comprehensive approach, where social and cultural sustainability is at the core of every SDGs, needs to be developed and implemented successfully and sustainably. This will require a new form of urban governance where the sustainability of heritage-led urban regeneration in World Heritage Cities is not measured in monetary terms only but in relation to improved living conditions for local communities and their level of engagement and participation in decision-making, ensuring that their living intangible heritage and its continuation and adaption into the future by new generations is a key factor for a socially, culturally, environmentally, and economically sustainable future. This feeds back the concept of wisdom and does so by employing an exploration of how being wise might relate to being critical [57]. It is necessary to go beyond the mere description and explanation of the spatiality of social phenomena by incorporating particular aspects of existing UN initiatives to address on-the-ground issues rather than criticizing them. What is needed is a more encompassing and forward-looking wise stance. The SDG platform’s end threshold in 2030 starts a new 15-year cycle that should consider all aspects of sustainability, including social and cultural sustainability. Therefore, the importance of this paper is to point out how this can be achieved.

The relevant SDG targets and indicators should also be refined to include the community’s performativity, livability, diversity, and well-being. Both UNESCO WHL and the SDGs are initiatives led by the UN for a more sustainable future and the well-being of future generations. The concept of sustainability is widely discussed in conferences and research papers. However, its ideological functionality may be declining based on changes in trends or economic concerns [58] due to the lack of a comprehensive understanding of what being truly critical and piercing about this ideology reveals. Therefore, the SDG platform should address its shortcomings by identifying what “sustainability” is and by linking it to culture and social sustainability as priority pillars that are at the core of economic and environmental sustainability pillars. This is to ensure that both tangible and intangible heritage are preserved and included in the framework of the SDGs.

This paper further suggested a more comprehensive approach to promoting sustainable heritage-led urban regeneration alternatives for cities acquiring UNESCO WH status. This is to rebalance cultural and social priorities in the most relevant SDGs, which are SDG-8 (8.1, 8.3, and 8.9), SDG-11 (11.3, 11.4, and 11. a), and SDG-17 (17.16, 17.17, 17.18, and 17.19). The suggestion is to integrate aspects from the other two UN initiatives: the Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) and the New Urban Agenda (NUA). Synergies and correlations among the three initiatives can be made using a critical content analysis and the NVivo qualitative analysis tool. This is to develop and curate a more comprehensive set of goals promoting sustainable heritage-led urban regeneration alternatives for cities acquiring UNESCO WH status. The suggested approach would help overcome the shortcomings of the SDGs in terms of social and cultural sustainability. This concept addresses and integrates already established UN initiatives rather than creating new ones. The SDGs’ platform is the primary reference for developing the integrated approach, as a policy document is already in place to ensure the link with the UNESCO World Heritage Convention [26].

Furthermore, many countries address and include the SDGs in their action framework. In fact, 2014 witnessed the formation of new working groups, bringing together the work of ICOMOS and those working on 2030 Sustainable Development Goals under the umbrella of the United Nations. This working group is currently working on actions to localize and nationalize a version of the ICOMOS SDGWG document “Heritage and The Sustainable Development Goals: Policy Guidance for Heritage and Development Actors” [26]. Although many of these initiatives acknowledge that culture is underrepresented in the SDGs, none of the above initiatives addressed the shortcomings of the SDGs from a social and cultural standpoint before adapting them in their framework. Therefore, this paper is a timely opportunity to suggest how these initiatives can be incorporated to overcome the shortcomings of the SDGs and ensure that all pillars of sustainability are covered to avoid the negative aspects of urban regeneration that tend to follow WH listing. This integrated approach with the other UN initiatives will aid this paper in being highly valued within these platforms and cities pursuing the UNESCO inscription or already on the WH list.

There is a rising awareness of the need to incorporate different UN initiatives together and include and activate the role of culture and heritage. For example, UNESCO is identifying areas of correlation between the HUL approach and the SDGs [59]. In contrast, others try to correlate the NUA and the SDGs, such as the Compass Housing Services [60], the United Nations Human Settlements Program [30], the General Assembly of Partners in 2021 [61], and some academics [62,63,64]. Others research heritage or culture as an enabler to achieve the SDGs [21,22,23,24,25]. This is in addition to the formation of the ICOMOS working group dedicated to including heritage and culture as a primary driver to achieve the SDGs called ICOMOS-SDGWG, of which the author is an active member and one of the three representatives for ICOMOS-Jordan under the title of SDGWG/ICOMOS-NC Jordan [21]. These are timely recent initiatives still in progress with no published outcomes yet; all have stopped at positioning culture and heritage among one or two selected initiatives.

9. Conclusions

There are many shortcomings of the SDGs in addressing social and cultural sustainability as an equal pillar of sustainability as economic and environmental sustainability, despite all the efforts made by many platforms that are dedicated to integrating and localizing culture among the SDGs (e.g., culture 21 committee of UCLG, 2018; CIVVIH/ICOMOS, 2020; ICOMOS-SDGWG, 2020; and others). There are many challenges and difficulties in attaining adequate data and developing systematic methodologies for cultural heritage to realize and measure the progress of the SDGs. Therefore, relevant SDG indicators do not correlate with their affiliated targets, with most indicators measured by the expenditure spent to achieve them. Thus, aspects related to social and cultural sustainability are excluded, leading to many shortcomings of the SDGs that impact the local communities and tangible and intangible heritage in WH cities. The consequences of those shortcomings are visible from the adopted case study of As-Salt in Jordan, inscribed on the WHL in July 2021. Although Jordan already signed and adopted the SDGs in 2015, regeneration in the city has often translated to a proliferation of hotels, bed-and-breakfast accommodations, souvenir shops, and many other tourist-oriented leisure and catering facilities [9]. This has led to the alienation of the local community and the neglect of its intangible heritage that—in this case—formed the site’s Outstanding Universal Value (OUV). This case has clearly shown that monitoring and measuring the successful implementation of the SDG targets is problematic. The undermining of social and cultural sustainability in the indicators may lead to undermining intangible heritage preservation and neglecting community needs.

Both UNESCO WHL and the SDGs are initiatives led by the UN to promote a more sustainable future and the well-being of future generations [44]. Therefore, the SDG platform should address its shortcomings and linkages with culture and social sustainability as equal pillars to sustainability as economic and environmental pillars. This is to ensure that both tangible and intangible heritage are preserved and included in the framework of the SDGs. It was concluded in this paper that to address this issue, other initiatives from the UN corpus for sustainable development can be incorporated under the umbrella of the SDGs. These initiatives are the Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) and the New Urban Agenda (NUA). The other two initiatives do not cover many aspects but can be addressed. These initiatives are used along with the SDGs to build an integrated approach toward sustainable development. The suggested approach would help overcome the shortcomings of the SDGs in terms of social and cultural sustainability. The SDG platform is the main reference for developing the integrated approach, as a policy document is already in place to ensure the link with the UNESCO World Heritage Convention [26]. A critical content analysis using a qualitative analysis tool (NVivo) identified the correlations and the areas of overlapping among the three initiatives. This was performed to develop a refined set of criteria and targets for the SDGs, mainly for historic and WH cities. Adopting this integrated approach makes it more likely to retain tangible and intangible heritage components that connect local communities to their heritage.

Finally, UNESCO has made many subsequent efforts to extend heritage protection into the sustainable development paradigm, most notably with the 2011 Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape and the 2015 Policy Document for integrating a Sustainable Development Perspective into the processes of the World Heritage Conventions. However, progress in making this shift in World Heritage practice is still described as a piecemeal approach. It is to be acknowledged that addressing this issue is a shared responsibility, starting from UNESCO and moving to local governments and the local communities. However, UNESCO and other international bodies should also provide state parties with more guidance and additional recommendations on localizing and nationalizing frameworks to meet the other UN initiatives already in place, especially the current UN Sustainable Development Goals.

This paper proposed an approach for a more comprehensive framework that equally considers all pillars of sustainability. Further research is needed to cover all the targets and indicators of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This paper revealed that culture and heritage are embedded within all the SDGs, emphasizing the importance of social and cultural sustainability in promoting stakeholders’ resilience and inclusiveness toward accepting all values within the site boundaries.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.F.E.F. and M.S.; methodology, B.F.E.F. and M.S.; software, B.F.E.F.; validation, B.F.E.F. and M.S.; formal analysis, B.F.E.F.; investigation, B.F.E.F. and M.S.; resources, B.F.E.F.; data curation, B.F.E.F.; writing—original draft preparation, B.F.E.F.; writing—review and editing, B.F.E.F. and M.S.; visualization, B.F.E.F. and M.S.; supervision, M.S.; project administration, B.F.E.F. and M.S.; funding acquisition, B.F.E.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

As-Salt local community survey was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Welsh School of Architecture, School Research Ethics Committee, CF10 3NB on 12 October 2020.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in As-Salt local community survey at the heart of this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This paper is a part of the leading author’s PhD research, sponsored by the Hashemite University in Jordan.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acronyms and Abbreviations

| UNESCO | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization |

| UN | United Nations |

| WHL | World Heritage List |

| UNESCO | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization |

| OUV | Outstanding Universal Value |

| ICOMOS | International Council on Monuments and Sites |

| WHS | World Heritage Site |

| HUL | Historic Urban Landscape |

| NUA | New Urban Agenda |

| SDGWG | Sustainable Development Goals Working Group |

References

- WCED. Our Common Future; WCED: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J. The 2030 agenda for sustainable development and China’s implementation. Chin. J. Popul. Resour. Environ. 2017, 15, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landorf, C. A Framework for Sustainable Heritage Management: A Study of UK Industrial Heritage Sites. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2009, 15, 494–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P. The Governance of sustainable development in Wales. Local Environ. 2006, 11, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogruyol, K.; Aziz, Z.; Arayici, Y. Eye of Sustainable Planning: A Conceptual Heritage-Led Urban Regeneration Planning Framework. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN. Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; UN Doc. A/RES/70/1 (25 September 2015); UN: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. UNESCO Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/hul/ (accessed on 16 March 2024).

- United Nations UN. The New Urban Agenda|Urban Agenda Platform. Available online: https://www.urbanagendaplatform.org/nua (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- El Faouri, B.F.; Sibley, M. Heritage-Led Urban Regeneration in the Context of WH Listing: Lessons and Opportunities for the Newly Inscribed City of As-Salt in Jordan. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, C. The UNESCO imprimatur: Creating global (in)significance. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2020, 26, 845–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orbaşlı, A. Urban heritage in the Middle East: Heritage, tourism and the shaping of new identities. In Routledge Handbook on Tourism in the Middle East and North Africa; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 95–105. [Google Scholar]

- Gharib, R.Y. Revitalizing Historic Cairo: Three decades of policy failure. ArchNet-IJAR Int. J. Archit. Res. 2011, 5, 40. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker, H.; Carnegie, E. World heritage and the contradictions of “universal value”. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 47, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, L.; Frey, B.S. Imbalance of World Heritage List: Did the UNESCO Strategy Work? University of Zurich, Economics Working Paper; University of Zurich: Zürich, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bagader, M. The impacts of UNESCO’s built heritage conservation policy (2010–2020) on historic Jeddah built environment. WIT Trans. Built Environ. 2018, 177, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Yung, E.H.K.; Chan, E.H.W.; Xu, Y. Sustainable Development and the Rehabilitation of a Historic Urban District—Social Sustainability in the Case of Tianzifang in Shanghai. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 22, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soini, K.; Birkeland, I. Exploring the scientific discourse on cultural sustainability. Geoforum 2014, 51, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meskell, L. The rush to inscribe: Reflections on the 35th Session of the World Heritage Committee, UNESCO Paris, 2011. J. Field Archaeol. 2012, 37, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]