Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to significant transformations in industries globally, particularly those heavily reliant on human interaction, such as the event industry. However, the effects of COVID-19 on the event industry have not been thoroughly explored in previous studies. This study utilizes secondary data from the Korean Statistical Information Service, covering 16 cities and regions from 2018 to 2022, to analyze the effects of COVID-19 on the event industry and how the pandemic has reshaped the sector’s landscape and sustainability. We employed a Regression Discontinuity Design (RDD) model to assess the causal impact and utilized Garthwaite’s (2014) Dynamic Discontinuity model to explore the dynamic effects over time. The results demonstrate that, initially, COVID-19 had a considerable disruptive influence on the event industry, severely affecting face-to-face interactions and operations. However, our findings reveal significant signs of adaptation and recovery in the industry by 2022, with the initial negative impacts no longer evident. This study highlights the event industry’s resilience, the progressive nature of its post-pandemic recovery, and its path toward sustainable practices in a post-pandemic era.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic, which originated as a singular health crisis, quickly transformed into a complex polycrisis affecting social, economic, political, and environmental dimensions [1]. Consequently, the pandemic has undeniably exerted a profound impact across the global economy, reshaping industries and altering consumer behaviors [2]. In-depth studies have elucidated various dimensions of this impact, detailing shifts in supply chain dynamics [3,4], alterations in consumer spending patterns [5], COVID-19 recovery in a city [6], and the accelerated adoption of digital technologies [7]. These research efforts have significantly enhanced our understanding of the pandemic’s broad economic repercussions [8], offering insights into resilience strategies [9] and adaptive measures employed by different sectors.

Despite the extensive body of research, the quantitative impact of the pandemic on the industries reliant on human interaction, such as the event industry, remains underexplored [10]. This industry, crucial both economically and culturally, plays a significant role in local and national economies by generating direct and secondary spending and fostering community engagement and cultural exchange [11,12,13,14]. For instance, events provide platforms for artistic expression, education, and networking [13]. They serve as a catalyst for cultural vibrancy, innovation, and the exchange of ideas, enriching societies and fostering a sense of identity and unity among participants [14]. However, the inherent requirement for face-to-face interaction within this sector has led to heightened vulnerability to the pandemic’s disruptions, revealing a critical gap in empirical research focused on the event industry’s specific challenges and responses during the pandemic [14,15,16]. So, this study aims to address this gap by focusing on the resilience and recovery strategies within the meetings, incentives, conferences, and exhibitions (MICE) sector during and after the pandemic. Specifically, we analyze the direct and indirect effects of COVID-19 on key economic metrics within the event industry—specifically the number of businesses, employment levels, sales revenue, and operating profit. Also, through regression analysis incorporating COVID-19 as a primary independent variable, we explore the pandemic’s role as a major disruptor and gauge the industry’s response and recovery patterns without assuming the implementation of specific recovery strategies as part of the model’s independent variables.

Based on the findings from our model, we highlight the event industry’s initial significant disruptions in 2020 and its subsequent adaption and recovery, revealing a progressive movement towards sustainable practices by 2022. Initially, the sustainability of the event industry came into sharp focus in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic [17,18]. COVID-19 had a considerable disruptive influence on the event industry, severely affecting face-to-face interactions and operations. Our results reveal that the initial negative impacts on the event industry are no longer evident in the post-pandemic era.

Our study also emphasizes the resilience of the MICE sector during the pandemic. The industry’s ability to quickly pivot to virtual and hybrid event formats demonstrates significant adaptability. These innovations not only provided immediate solutions during lockdowns but also opened up new avenues for future growth and sustainability. The rapid adoption of digital platforms and technologies allowed the MICE sector to maintain engagement with their audiences, ensuring continuity and minimizing financial losses. By 2022, many MICE events successfully integrated in-person and virtual elements, creating a robust hybrid model that could withstand future disruptions.

By examining the enduring changes and emerging trends within the event industry, this study not only contributes to the academic discourse but also provides practical insights for industry stakeholders, policymakers, and planners. We aim to offer a comprehensive analysis that can inform future strategies, ensuring the sector’s robust recovery, sustainable growth, and resilience in the era of the new normal [19].

Following this introduction, the paper will continue with a literature review, laying the foundational groundwork by examining existing studies that illuminate the impact of COVID-19 across various industries, with a particular emphasis on the event sector. Subsequently, we will present our forecasts concerning the pandemic’s influence on the event industry, supported by a comprehensive overview of the data and methodologies utilized in our analysis. Finally, we will conclude this study by summarizing the findings and discussing both the theoretical and practical implications, as well as acknowledging the limitations of the current research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. COVID-19 and Changes in the Korean Event Industry

2.1.1. Digital Transformation of the Event Industry

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to significant transformations in the global event industry. Industries worldwide have experienced a shift towards digitalization and environmentally sustainable management [20]. The event industry, traditionally focused on offline interactions, has been compelled to embrace digitalization due to the pandemic’s unique challenges [21]. This shift has necessitated rapid adaptation and the development of new business models to enhance profitability and sustainability [22].

2.1.2. Digital Transformation of the Event Industry in Korea

The event industry in Korea has undergone significant changes due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The most notable transformations include digitalization and environmentally sustainable management. Initially less inclined towards digitalization, the Korean event industry had to adapt quickly for survival. Digital transformation policies aimed to innovate traditional events through virtual and hybrid platforms, online registration, virtual exhibitions, and enhanced online communication [23]. Metaverse platforms and hybrid events have become more prevalent, allowing participation without the constraints of time and space and combining the benefits of both online and offline elements [24]. Additionally, there has been a growing adoption of environmentally sustainable practices, such as waste reduction, recycling, and carbon emission mitigation, accelerated by the pandemic [25]. In response to COVID-19, the Korean event industry has also focused on sustainability efforts, aiming to obtain global environmental certifications like LEED, ISO, and carbon-neutral certification.

2.2. Previous Studies on the Impacts of COVID-19 and Hypothesis Development

2.2.1. Global Impact of COVID-19 on the Economy

The COVID-19 pandemic has had significant impacts on the global macroeconomic landscape [26]. The pandemic led to a sharp economic contraction in 2020, with the global GDP decline estimated to be between 3.0% and 6.5% for that year [27,28]. This was the deepest global recession since the Great Depression [29]. Lockdowns [30], travel restrictions [31], and other containment measures disrupted supply chains and reduced consumer spending [32], leading to a collapse in demand across many industries. This resulted in high unemployment rates in many countries [33].

Governments responded with unprecedented fiscal and monetary stimulus to support households and businesses, including direct payments, expanded unemployment benefits, and central bank interventions [34,35]. This helped mitigate the economic damage but also led to rising public debt levels. The pandemic accelerated certain economic trends, such as the shift towards remote work and e-commerce [36]. This has had implications for commercial real estate [37], transportation [38], and other sectors. Recovery has been uneven across sectors and regions, with some industries like technology thriving and others, such as events, requiring in-person attendance, and hospitality and commercial passenger transportation struggling. Developing economies have generally fared worse than advanced economies. There are concerns about the long-term scarring effects of the pandemic on productivity, investment, and potential output growth [39]. The pandemic may also exacerbate existing inequalities within and across countries [40].

2.2.2. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Event Management and Tourism Industries

The pandemic has particularly affected industries reliant on direct human interactions, notably those necessitating large group gatherings like meetings, exhibitions, concerts, and assorted events [23]. The COVID-19 pandemic significantly impacted the event management industry globally, particularly affecting the USD 1000 billion event planning sector [41]. The enforcement of social distancing regulations, lockdowns, and travel restrictions has severely disrupted these sectors. For example, the MICE (meetings, incentives, conventions, and exhibitions) sector faced a sharp decline in demand. Additionally, hotels and other tourism-related businesses suffered significant financial losses. Specifically, there was an 82% decrease in scheduled departure flights [42]. Essential revenue sources for these industries, including registration fees, ticket sales, on-site expenditures, sponsorships, venue rental fees, and advertising revenues, have experienced a marked decline due to widespread event cancellations and postponements. This disruption highlights the vulnerability of such industries to global crises and underscores the need for adaptive strategies to mitigate the impact of such unprecedented challenges.

2.2.3. Hypothesis Development

Industries such as exhibitions, conventions, and events heavily rely on support service providers and contract workers, whose financial stability was jeopardized when events were halted. In response, some entities and performers pivoted to digital means to keep in touch with their customers, participants, and audiences, using online streaming, virtual events, and digital workshops. This transition opened up new avenues for revenue, though it did not entirely substitute the experience of in-person attendance.

Therefore, the COVID-19 pandemic led to restrictions and cancellations of large gatherings and events. This resulted in significant economic losses for the event industry, with many companies reducing operations or shutting down completely. The initial uncertainty and increased regulations made it difficult to hold events, which negatively impacted the overall industry. Based on the above reasoning, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1.

COVID-19 has had negative impacts on the event industry.

However, amid the COVID-19 pandemic, the MICE sector implemented immediate strategies to reassess operational costs and adjust business models by integrating virtual events to facilitate recovery and resilience efforts [43]. However, rather than being short-term solutions, digital technologies were leveraged to enhance the overall event experience for attendees and optimize business opportunities for each event [44]. Key findings also highlight the agility of entrepreneurs, significant technological advancements spurred by COVID-19, the emergence of hybrid events as a new industry standard, and the critical role of adopting new technologies to maintain competitiveness [45]. The pandemic is poised to cause enduring shifts in how these industries operate and are perceived, potentially altering the design and management of large-scale events, as well as the standards for hygiene, safety, and virtual engagement. The event industry is always mindful of the possibility of another pandemic arising unexpectedly. Despite the lack of short-term benefits, many believe that prioritizing the establishment of a business environment capable of remote operation in the long term is crucial. Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, numerous event companies have been conducting virtual conferences, creating digital exhibition spaces, and incorporating live streaming alongside traditional in-person events for this reason.

The event management sector stands as a pivotal component of the global economy, orchestrating activities that resonate across various economic sectors and yielding significant financial gains. By meticulously planning and executing a myriad of events, ranging from high-profile conferences to specialized trade shows and cultural festivals, event management not only promotes international trade and stimulates economic output but also fosters employment. This industry, as per the World Travel & Tourism Council, was estimated at a staggering USD 1.5 trillion in 2019, supporting over 26 million jobs worldwide [46]. This sector’s influence extends to boosting expenditures in associated services like venue rentals, catering, and logistics, thereby serving as a linchpin for economic expansion.

Beyond its direct financial contributions, event management plays a crucial role in fueling tourism and hospitality, drawing a global audience that, in turn, invigorates local economies. Attendees contribute to the vibrancy of host cities through accommodation bookings, dining, and tourism, which not only augments local revenue but also prompts infrastructural enhancements. Moreover, events act as a crucible for networking and the exchange of knowledge, fostering innovation and business opportunities. By congregating professionals and thought leaders, event management facilitates a synergy that propels industry advancements and economic growth, underscoring its indispensable value to the broader economic landscape.

While the event industry faced significant challenges due to COVID-19 initially, over time, human adaptability and innovative solutions helped mitigate these negative impacts [47]. For example, many events transitioned to online formats, and hybrid events were introduced [48]. People started to gather in new ways, and with technological advancements, the event industry evolved into new forms [49]. These changes offset the short-term negative effects and provided opportunities for the industry to recover and grow in the long term. Due to human adaptability, the initial negative impacts did not persist.

H2.

COVID-19 initially had negative impacts on the event industry, but these negative effects diminished in the long term.

Despite the undeniable importance of the event industry within the global economy, there is a notable scarcity of empirical research examining the pandemic’s impact on this sector and whether its effects are persisting or subsiding [50]. This lack of data has hindered a comprehensive understanding of how COVID-19 has reshaped the landscape of events, affecting economic output, employment, and related industries. Therefore, systematic investigations are needed to provide insights into the pandemic’s long-term effects on the event industry, informing strategies for recovery and future resilience. The following section summarizes existing research on strategies for recovery and resilience from COVID-19.

2.2.4. Resilience and Adaptation of the Event Industry and MICE Sector Post-COVID-19

As detailed in this section, we reviewed previous research on the resilience of the event industry and MICE (meetings, exhibitions, congresses, and events) sector as the COVID-19 pandemic ends and the transition to a new normal era occurs. Yang and Smith (2023) [51] measured the resilience of the tourism and outdoor activities industry to COVID-19 using publicly available data for all regions of the United States. Khlystova et al. (2022) [52] reviewed the positive and negative impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on creative industries and developed a response matrix that takes into account a company’s digital capabilities and ability to respond to the COVID-19 crisis. Orthodoxou et al. (2021) [53] surveyed perceptions of sustainability among 71 business event stakeholders in Cyprus. The results of this study show that, currently, few sustainability practices are implemented within business event organizations and the demand for sustainability is relatively low. But, importantly, the emergence of a sustainable business events sector can also contribute to post-COVID-19 recovery. Werner et al. (2022) [54] used qualitative, semi-structured interviews to investigate the perspectives of event stakeholders (experts, instructors, and students) on necessary future skills in China, Germany, and Australia. Dillette and Ponting (2021) [23] emphasized that the extensive utilization of webinars, social media, and digital communication software offers event management professionals a universally accessible means to maintain communication and connectivity, even after the pandemic (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of previous studies.

3. Empirical Results

3.1. Data Description

We sourced the data for our research from the Korean Statistical Information Service, commonly known as KOSIS.KR (https://kosis.kr/index/index.do (accessed on 1 April 2024)). Managed by Statistics Korea, this official online platform functions as a comprehensive repository of statistical data pertinent to South Korea. It provides diverse statistics on demographics, economics, social issues, and more, meeting the needs of researchers, policymakers, and the general public. The platform facilitates data-driven decision making by offering detailed datasets essential for economic analysis, social studies, and market research. It includes tools and resources that enhance data accessibility and usability, making it an invaluable asset for anyone requiring authoritative statistical data on South Korea. Since 2016, the South Korean government has annually surveyed the performance of the event industry in the country, encompassing exhibition and international conference organizers, facility rental companies, service providers, venue rental companies, and equipment design and installation firms.

Annually, surveys are conducted involving approximately 2600 companies in South Korea’s event industry. These surveys collect key metrics such as the number of events hosted, employment statistics, annual revenue, operating profits, and other relevant performance indicators. Since 2018, statistical data have been provided based on 16 cities and regions. Therefore, we conducted an empirical study over a five-year period, from 2018 to 2022, using statistical data from these 16 areas. This approach allowed us to thoroughly investigate regional trends and differences within the dataset. The dataset includes both online and offline activities. This consistent dataset enables an analysis of the industry’s performance before, during, and after the pandemic, providing a comparative overview using the same group of companies each year. This information is vital for a comprehensive assessment of the pandemic’s impact on the event industry in South Korea. In our study, we aimed to analyze these data to understand how the pandemic has affected the event industry, focusing on variations in these key performance indicators over time.

In our research, we focused on four key metrics: the number of businesses, the number of employees, sales revenue, and operating profit. The unit of measurement for sales revenue and operating profit is in millions of Korean won. By concentrating on these variables, we sought to elucidate the causal impact of COVID-19 on the event industry, as well as the dynamic impact over time. This approach enabled us to understand not only the immediate effects of the pandemic but also its prolonged influence on the industry’s economic health.

Table 2 displays the summary statistics for the main variables used in our research. To normalize the four key metrics—number of businesses, number of employees, sales revenue, and operating profit—we applied a log transformation. We log-transformed the dependent variables to address skewness in the data, making the distribution closer to a normal distribution [55]. For operating profit, where the minimum value is −40,210 (in millions of Korean won), we adjusted the values by adding 40,211 to ensure all figures are positive before the transformation. This adjustment is necessary to apply the log transformation as it is undefined for non-positive values. We use the log-transformed per-capita personal income of South Korea to control for fluctuations in macroeconomic variables. On average, there are about 160 businesses and approximately 925 employees in each sector across South Korea

Table 2.

Summary statistics of the main variables based on yearly data from 2018 to 2022.

Table 3 presents the correlation matrix of the main variables. The four key metrics—number of businesses, number of employees, sales revenue, and operating profit—are all significantly positively correlated.

Table 3.

Correlation matrix of the main variables based on yearly data from 2018 to 2022.

3.2. Empirical Approach

3.2.1. Causality Impact Model

Before analyzing the dynamic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the event industry, we initially assessed its immediate impacts using Regression Discontinuity Design (RDD). RDD is a commonly employed method for determining the causal effects of a specific intervention [56]. This is achieved by comparing outcomes between two groups located around a predetermined threshold in an assignment variable (Treatment). In our study, we aimed to determine the causal impact of COVID-19; thus, COVID-19 served as the Treatment. When examining the impact of COVID-19 on the event industry using RDD, the presence of a causal impact implies a discontinuity at the threshold (2020 and beyond). This discontinuity enables us to observe the various effects of COVID-19 on the event industry. By identifying and analyzing this break in the data at the point where the pandemic began, we can discern the direct consequences of the virus on different aspects of the industry, thereby isolating the causal influence of the pandemic. In our first study, we explored the pandemic’s causal effects using annual data from South Korea’s event industry over a five-year period, from 2018 to 2022. To assess the findings from the linear regression, we conducted an analysis using a fixed effect model:

We employ the following RDD model specification:

where l represents location and t represents year. denotes the dependent variables. The variable serves as the treatment indicator; it is a binary variable set to 1 for observations in 2020 and beyond, and 0 otherwise. The variable d acts as the running variable (R.V.), a linear metric that measures the number of years relative to 2020, our chosen cutoff year, indicating the time distance from the start of the pandemic. The model is designed to accommodate varying coefficients for the assignment variable on both sides of this threshold, allowing for the computation of distinct coefficients for each side. is crucial to our analysis, representing the shift in the event industry beginning in 2020, which is our primary focus. are dummy variables introduced to control for fixed effects associated with each year, aiming to isolate the impact of yearly economic fluctuations by incorporating year-specific fixed effects. The term is used to control for location-specific fixed effects, which could be cities or states. represents the stochastic standard errors in our model.

3.2.2. Empirical Results of the Causal Impact Model

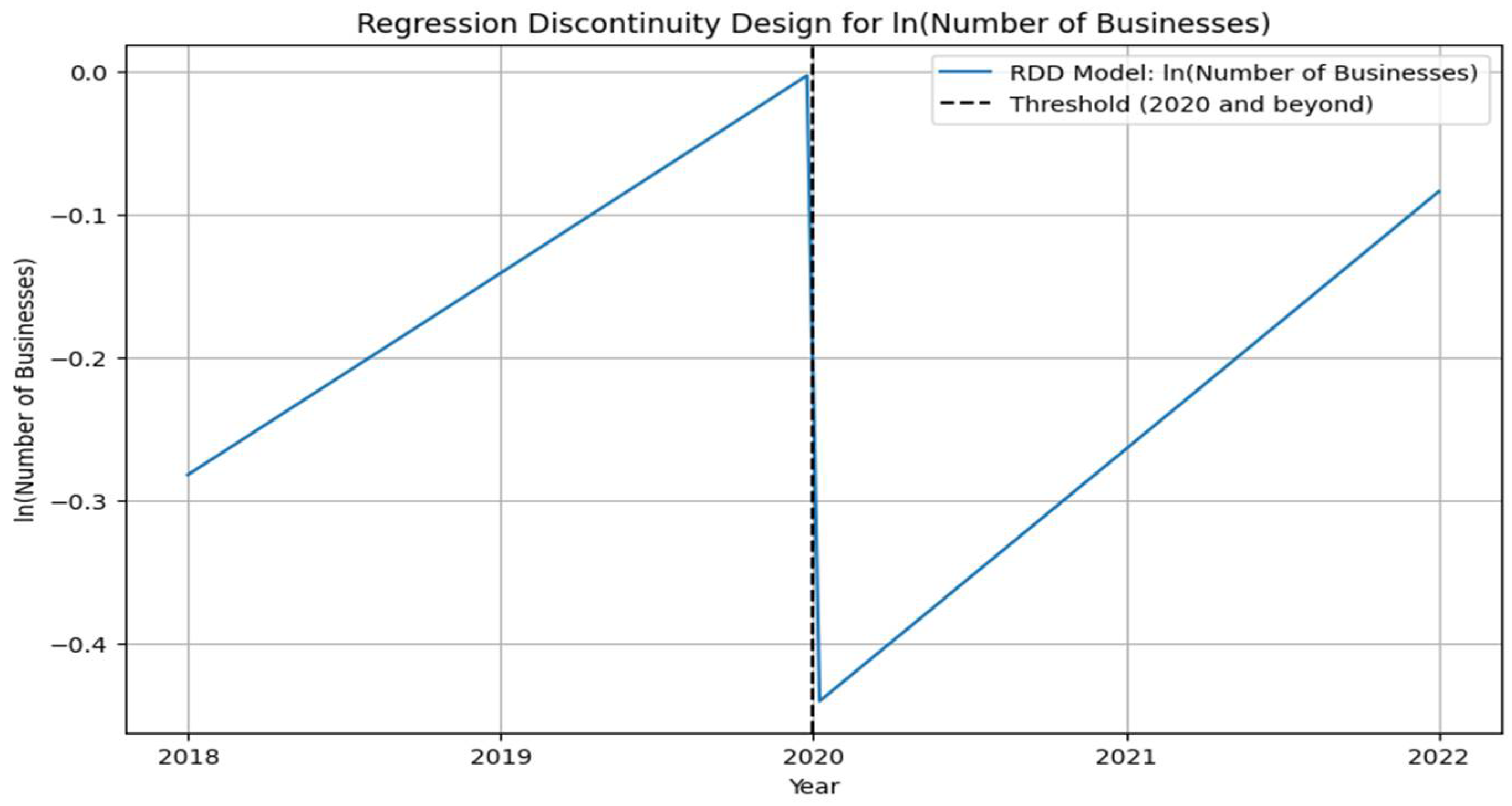

Table 4 presents the empirical results from the RDD model described earlier. In the table, the estimated coefficient for the Treatment variable (2020 and beyond) quantifies the causal impacts of COVID-19 on the dependent variables. In Model (1), the coefficient of treatment for the log-transformed number of businesses is significantly negative (βTreatment = −0.444, p-value < 0.01), indicating that COVID-19 had a detrimental impact on the log-transformed number of businesses operating in the event industry.

Table 4.

Empirical results of Regression Discontinuity Design.

Similarly, the negative impacts of COVID-19 on the event industry are confirmed through the estimated coefficients of Treatment for the number of employees, sales revenue, and operating profit. The estimated coefficient of Treatment for the log-transformed number of employees is significantly negative (βTreatment = −0.920, p-value < 0.01), that for the log-transformed sales revenue is significantly negative (βTreatment = −1.124, p-value < 0.01), and that for the log-transformed operating profit is also significantly negative (βTreatment = −2.519, p-value < 0.01). On the other hand, the estimated coefficients on both sides of the threshold (Treatment) are insignificant, indicating that there was no noticeable trend in the event industry from 2018 to 2022. The negative impact was solely attributed to COVID-19. This finding naturally leads us to the subsequent question of whether the negative impacts persisted until the end of 2022 or if the industry’s responses, such as digital transformation, could mitigate these effects. To address this query, we employed the approach (Dynamic Discontinuity model) developed by Garthwaite (2014) [57], who analyzed the dynamic impacts of celebrity endorsements on book sales over time.

Figure 1 illustrates the impact of COVID-19 on the number of businesses based on the estimated coefficients from Model (1). The x-axis represents the years from 2018 to 2022, with 2020 as the threshold marking the onset of the pandemic. The significant drop in the ln(Number of Businesses) post-2020 indicates the negative effect of the pandemic.

Figure 1.

Causal Impact of COVID-19 on number of businesses.

3.2.3. Dynamic Impact Model

Celebrity endorsements are often regarded as external disturbances or “exogenous shocks” due to their transient effects. Garthwaite (2014) [57] utilized time dummy variables in linear regression models to assess how these endorsements temporarily boost book sales. By including these time-specific variables, he examined the ephemeral impacts of celebrity endorsements, capturing how their effects peak and then diminish over a defined period. This approach enabled an analysis of the dynamic relationship between celebrity endorsements and book sales, acknowledging the temporary nature of their influence. Consequently, if celebrity endorsements significantly impact book sales, this effect will be evident in the time dummy variables incorporated in the model, demonstrating a sharp discontinuity during the period of influence. This discontinuity provides a clear indication of the temporal effects of endorsements on sales dynamics, as confirmed by the estimated coefficients of the time dummy variables in the model.

In the model specification outlined below, the onset of COVID-19 is treated as a random event, akin to an unforeseen shock. This approach facilitates the examination of the pandemic’s effects on our key dependent variables, including the number of businesses, the number of employees, sales revenue, and operating profit. To effectively analyze these effects within our regression models, we included year dummy variables that represent the period impacted by COVID-19, known as the “COVID-19 period”. These variables allow us to specifically identify and analyze the dynamic effects of the pandemic on the variables being studied and to assess the statistical significance of these effects. By considering COVID-19 as an external shock and incorporating it into our regression models, we gain valuable insights into the pandemic’s impact on the variables we are investigating.

where l refers to location and t represents year. In the above model specification, we define the dependent variables (Dependent Variableslt) as the number of businesses, number of employees, sales revenue, and operating profit. We incorporated a stochastic error term (εlt) to capture any variations in the dependent variables that are not explained by the model. By analyzing the relationship between independent variables (time dummy variables—indicator variables), including the COVID-19 period and other controls, with the dependent variables, we aim to understand the effects and dynamics of COVID-19 on these metrics. Our analysis employs a fixed-effect linear regression based on the described model specification.

In our model, the estimated coefficients of the indicator variables are of particular interest. Specifically, the βl coefficients are designed to reflect the variations in the dependent variables for a specific year “l” following the emergence of COVID-19. We utilize a specific indicator function named to denote this effect. This function assigns a value of 1 if the data year corresponds to the “l” year since the pandemic began, and 0 otherwise. The inclusion of these indicators in our regression analysis allows us to examine the sustained effects of COVID-19 on the four primary metrics across a span of three years from the onset of the pandemic.

To address potential confounding factors and control for additional influences on the dependent variables, we incorporated per-capita personal income and year indicators I{Year} into the model. Additionally, since this a fixed-effect linear model, location-specific variations were controlled for. We log-transformed the four dependent variables and per-capita personal income to normalize the data.

3.2.4. Empirical Results of the Dynamic Impact Model

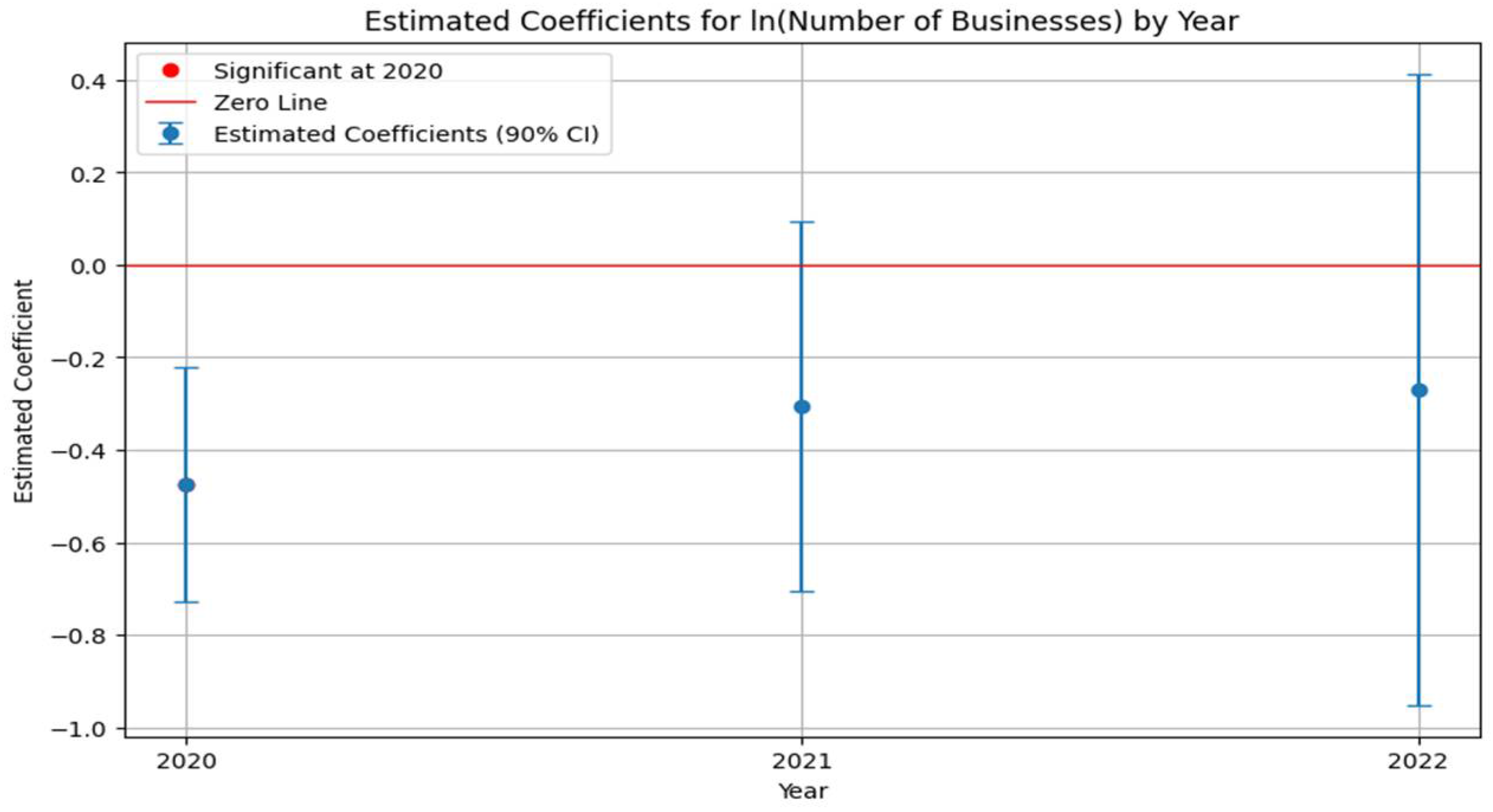

Table 5 shows the empirical results of the dynamic impact model. In Model (1), the analysis reveals that the negative impact of COVID-19 on the log-transformed number of businesses was significant in 2020, as indicated by the significantly negative coefficient (β2020 = −0.474, p-value < 0.05). However, this negative impact did not continue beyond 2020; the estimated coefficients for 2021 and 2022 are not significant (β2021 = −0.305, p-value > 0.10, and β2020 = −0.269, p-value > 0.10, respectively), indicating that the adverse effects did not persist in these years.

Table 5.

Empirical results of Dynamic Discontinuity Model.

In Model (2), the estimated coefficients for 2020 and 2021 are significantly negative (β2020 = −0.688, p-value < 0.01 and β2020 = −0.639, p-value < 0.10, respectively), indicating that the negative impact of COVID-19 on the log-transformed number of employees continued through 2021. However, the coefficient for 2022 is insignificantly negative (β2020 = −0.512, p-value > 0.10), suggesting that the negative impact did not persist into 2022.

In Model (3), the estimated coefficient for 2020 is significantly negative (β2020 = −0.668, p-value < 0.01), indicating that the negative impact of COVID-19 on the log-transformed sales revenue was pronounced in 2020. However, the coefficients for 2021 and 2022 are insignificantly negative (β2021 = −0.599, p-value > 0.10 and β2020 = −0.586, p-value > 0.10, respectively), suggesting that the negative impact did not persist beyond 2020 and effectively dissipated.

Lastly, it is evident that the negative impact of COVID-19 on the log-transformed operating profit persisted through 2021, as the estimated coefficients for 2020 and 2021 are significantly negative (β2020 = −1.996, p-value < 0.01 and β2020 = −2.058, p-value < 0.10, respectively). However, the coefficient for 2022 is insignificantly negative (β2020 = −3.178, p-value > 0.10), indicating that the negative impact ceased in 2022.

From the results presented in Table 4 and Table 5, we observed that COVID-19 had causally negative impacts on the four key metrics. However, these negative effects had dissipated by the year 2022.

Figure 2 shows the estimated coefficients for ln(Number of Businesses) by year. The red point for 2020 indicates a significant effect, while 2021 and 2022 are not significant at the 90% confidence level.

Figure 2.

Dynamic Impact of COVID-19 on number of businesses.

4. Conclusions

4.1. Summary of Findings

Our study analyzed the impact of COVID-19 on the event industry, focusing on essential economic metrics. Although we anticipated that the adverse effects of the pandemic would have largely subsided by 2022, the findings from Table 4 and Table 5 confirmed that COVID-19 had a causal negative impact on four key metrics: the number of businesses, the number of employees, sales revenue, and operating profit. In other words, the results indicate that despite the initial severe disruptions caused by the pandemic in 2020, there were significant signs of recovery by 2022. This rebound suggests an inherent resilience within the industry, possibly facilitated by a broad and rapid pivot towards digital and virtual engagement strategies.

The shift to digital platforms, increased utilization of virtual communication tools, and integration of hybrid event formats appear to have played crucial roles in mitigating the pandemic’s negative impacts. These changes, while initially responses to immediate needs, may have paved the way for enduring transformations in how events are planned, executed, and experienced, thereby enhancing the industry’ sustainability and resilience. For instance, a 2021 survey by the Korea Tourism Organization indicates that business event companies in South Korea are increasingly accelerating their digital transformation efforts. A total of 87.5% of respondents reported plans to host events in hybrid or online formats in 2021. This adaptation has not only helped mitigate the initial disruptions caused by the pandemic but also enhanced the industry’s sustainability, promising a more resilient future for the event sector in the post-pandemic world.

4.2. Theoretical and Practical Implications

4.2.1. Theoretical Implications

This study enhances the theoretical understanding of resilience [47] within the event industry by demonstrating how crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, catalyze rapid transformations across sectors [58]. It supports the theory that adversity fuels innovation, illustrating how the integration of digital technologies acts as a buffering mechanism against disruptions, thereby bolstering long-term sustainability. Moreover, our findings enrich dynamic capabilities theory [59] by showcasing how the event industry capitalized on its abilities to adapt to the new challenges posed by the pandemic. This swift adaptation and implementation of new technologies and strategies exemplify the sector’s dynamic capabilities, which are essential for survival, competitiveness, and sustainability during crisis situations.

4.2.2. Practical Implications

The findings of this study underscore the imperative for industries that depend heavily on human interaction, such as the event sector, to continually develop and integrate flexible and innovative solutions like digital platforms to mitigate future disruptions. With the expectation that pandemics may continue in the future (https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-022-03356-6 (accessed on 1 April 2024)), digital transformation is crucial for the sustainability of the event industry. Enhanced readiness is essential not only for basic survival but also for thriving in the aftermath of crises. Industry leaders and policymakers should leverage these insights to fortify disaster preparedness strategies and ensure sustainable growth.

UFI The Global Association of the Exhibition Industry (https://www.ufi.org/ (accessed on 1 May 2024)) predicts that in the future, most exhibitions will adopt a hybrid format, combining offline elements with features like video consultations and live streaming to enable real-time communication with customers. Additionally, virtual webinar-style conferences and meetings hosted on metaverse platforms, where anyone can participate regardless of time and space constraints, are expected to further develop. Through the integration of various digital communication channels, the event industry is anticipated to become more advanced and diversified. Leveraging accumulated big data, the scope of business is also expected to expand.

Furthermore, the event industry, which has been traditionally perceived as a major contributor to environmental pollution, is expected to transition into a more environmentally friendly and sustainable industry, with a focus on non-face-to-face interactions, recycling, and environmental, social, and governance (ESG) initiatives, catalyzed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Many prominent global events already provide ESG guidelines and evaluate participants accordingly.

Therefore, it is crucial for businesses within the event sector to prioritize investments in technology and employee training to boost digital literacy. This commitment will enhance the sector’s capacity to face similar challenges in the future, ensuring resilience and sustainability. By embracing these strategies, the event industry can set a precedent for other sectors, promoting a broader shift towards sustainable practices that balance economic needs with environmental considerations.

4.3. Limitations and Future Research

This study encountered several limitations that suggest avenues for future research. Firstly, the limited sample size constrains the generalizability of our findings. This limitation primarily stems from the availability of data from the Korean Statistical Information Service, which currently only extends up to 2022. As more data become available, it will be imperative to reassess and expand our analysis over a broader timeframe to enhance the robustness and applicability of the results.

Secondly, while our findings suggest that the negative impacts of COVID-19 on the event industry dissipated by 2022, potentially due to successful digital transformation, we are unable to definitively confirm the underlying mechanisms that facilitated this recovery. Future studies should explore these dynamics in greater depth. Surveys and interviews with industry professionals could provide valuable insights into how digital transformations and other adaptive strategies were implemented and perceived within the industry. Such qualitative data could enrich our understanding of the practical aspects of resilience and adaptation in the face of global disruptions, offering a more comprehensive view of the pathways through which the event industry has navigated the challenges posed by the pandemic, with a focus on long-term sustainability.

Lastly, future research should explore how the level of digital technology use and the stage of digital transformation in different cities influenced the impact of COVID-19 on the event industry. Neumann (2022) [60] highlights that smart district development, like Špitálka in Brno, enhances urban resilience and sustainability through digital solutions, potentially mitigating the negative effects of the pandemic. Thus, investigating the differential impacts on cities with varying degrees of digital transformation will provide insights into how digital integration can bolster the event industry’s resilience to crises and guide future urban development strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.-S.C.; methodology, J.-M.K.; validation, D.-S.C. and K.K.-c.P.; formal analysis, J.-M.K.; investigation, K.K.-c.P.; writing—original draft, D.-S.C., K.K.-c.P. and J.-M.K.; writing—review & editing, K.K.-c.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Matlovič, R.; Matlovičová, K. Polycrisis in the Anthropocene as Key Research. Folia Geogr. 2024, 66, 5–33. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, Y.K.P.; Li, X.; Lau, V.M.C.; Dioko, L.D. Destination governance in times of crisis and the role of public-private partnerships in tourism recovery from COVID-19: The case of Macao. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2022, 51, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foltynowicz, Z.; Łupicka-Fietz, A.; Jeszka, A.M.; Kowalczyk, D. Evolution of Social Competencies in Sustainable Supply Chains. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kähkönen, A.K.; Evangelista, P.; Hallikas, J.; Immonen, M.; Lintukangas, K. COVID-19 as a trigger for dynamic capability development and supply chain resilience improvement. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2023, 61, 2696–2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.; Sarkar, A.; Debroy, A. Impact of COVID-19 on changing consumer behaviour: Lessons from an emerging economy. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2022, 46, 692–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charnley-Parry, I.M.; Farrier, A.; Dooris, M.; Whitton, J.; Manley, J. Organisations and Citizens Building Back Better? Climate Resilience, Social Justice & COVID-19 Recovery in Preston, UK. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budd, J.; Miller, B.S.; Manning, E.M.; Lampos, V.; Zhuang, M.; Edelstein, M.; Rees, G.; Emery, V.C.; Stevens, M.M.; Keegan, N.; et al. Digital technologies in the public-health response to COVID-19. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 1183–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orlowski, L.T. The 2020 Pandemic: Economic repercussions and policy responses. Rev. Financ. Econ. 2021, 39, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appolloni, A.; Colasanti, N.; Fantauzzi, C.; Fiorani, G.; Frondizi, R. Distance learning as a resilience strategy during COVID-19: An analysis of the Italian context. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutte, G.J.; Markwell, K.; Wilson, E. An opportunity to build back better? COVID-19 and environmental sustainability of Australian events. Int. J. Event. Festiv. Manag. 2022, 13, 440–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolasinski, M.J.; Roberts, C.; Reynolds, J.; Johanson, M. Defining the field of events. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2021, 45, 553–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D.; Page, S.J. Progress and prospects for event tourism research. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 593–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jin, X. Event-based destination marketing: The role of mega-events. Event. Manag. 2019, 23, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seraphin, H. COVID-19: An opportunity to review existing grounded theories in event studies. J. Conv. Event Tourism. 2021, 22, 3–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhav, N.; Oppenheim, B.; Gallivan, M.; Mulembakani, P.; Rubin, E.; Wolfe, N. Pandemics: Risks, impacts, and mitigation. In Disease Control Priorities: Improving Health and Reducing Poverty, 3rd ed.; The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Janiszewska, D.; Hannevik Lien, V.; Kloskowski, D.; Ossowska, L.; Dragin-Jensen, C.; Strzelecka, M.; Kwiatkowski, G. Effects of COVID-19 infection control measures on the festival and event sector in Poland and Norway. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.; Comfort, D. The COVID-19 crisis and sustainability in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 3037–3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiksel, J. Designing resilient, sustainable systems. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2003, 37, 5330–5339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avraham, E. Recovery strategies and marketing campaigns for global destinations in response to the COVID-19 tourism crisis. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 26, 1255–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen, D. Sustainable event management: New perspectives for the meeting industry through innovation and digitalisation. In Innovations and Traditions for Sustainable Development? Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 259–275. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, W.G.; Fenton, A.; Ahmed, W.; Scarf, P. Recognizing events 4.0: The digital maturity of events. Int. J. Event. Festiv. Manag. 2020, 11, 47–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disimulacion, M.A.T. MICE tourism during COVID-19 and future directions for the new normal. Asia Pac. Int. Events Manag. J. 2020, 1, 11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Dillette, A.; Ponting, S.S.A. Diffusing innovation in times of disasters: Considerations for event management professionals. J. Conv. Event Tour. 2021, 22, 197–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, I. Events and online interaction: The construction of hybrid event communities. Leis. Stud. 2019, 38, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, S.; Kumar, A.; Luthra, S.; Garza-Reyes, J.A.; Nadeem, S.P. The adoption of environmentally sustainable supply chain management: Measuring the relative effectiveness of hard dimensions. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2020, 29, 3104–3122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitt, M.A.; Holmes Jr, R.M.; Arregle, J.L. The (COVID-19) pandemic and the new world (dis) order. J. World Bus. 2021, 56, 101210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J.K.; Weiss, M.A.; Schwarzenberg, A.B.; Nelson, R.M. Global Economic Effects of COVID-19: In Brief; Congressional Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rungcharoenkitkul, P. Macroeconomic effects of COVID-19: A mid-term review. Pac. Econ. Rev. 2021, 26, 439–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvatore, D. The US and the world economy after COVID-19. J. Policy Model. 2021, 43, 728–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caulkins, J.; Grass, D.; Feichtinger, G.; Hartl, R.; Kort, P.M.; Prskawetz, A.; Seidl, A.; Wrzaczek, S. How long should the COVID-19 lockdown continue? PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0243413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinazzi, M.; Davis, J.T.; Ajelli, M.; Gioannini, C.; Litvinova, M.; Merler, S.; Pastore y Piontti, A.; Mu, K.; Rossi, L.; Sun, K.; et al. The effect of travel restrictions on the spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak. Science 2020, 368, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunphy, C.; Miller, G.F.; Rice, K.; Vo, L.; Sunshine, G.; McCord, R.; Howard-Williams, M.; Coronado, F. The impact of COVID-19 state closure orders on consumer spending, employment, and business revenue. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2022, 28, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, F.; Bianchi, G.; Song, D. The long-term impact of the COVID-19 unemployment shock on life expectancy and mortality rates. J. Econ. Dyn. Control. 2023, 146, 104581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberola, E.; Arslan, Y.; Cheng, G.; Moessner, R. Fiscal response to the COVID-19 crisis in advanced and emerging market economies. Pac. Econ. Rev. 2021, 26, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girón, A.; Correa, E. Fiscal stimulus, fiscal policies, and financial instability. J. Econ. Issues 2021, 55, 552–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckers, J.; Weekx, S.; Beutels, P.; Verhetsel, A. COVID-19 and retail: The catalyst for e-commerce in Belgium? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 62, 102645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, J.; Phillips, G.M. COVID-19 losses to the real estate market: An equity analysis. Finance Res. Lett. 2022, 45, 102131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirachini, A.; Cats, O. COVID-19 and public transportation: Current assessment, prospects, and research needs. J. Public Transp. 2020, 22, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Vries, K.; Erumban, A.; van Ark, B. Productivity and the pandemic: Short-term disruptions and long-term implications: The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on productivity dynamics by industry. Int. Econ. Econ. Policy 2021, 18, 541–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiske, A.; Galasso, I.; Eichinger, J.; McLennan, S.; Radhuber, I.; Zimmermann, B.; Prainsack, B. The second pandemic: Examining structural inequality through reverberations of COVID-19 in Europe. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 292, 114634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madray, J.S. The impact of COVID-19 on event management industry. Int. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2020, 5, 533–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aburumman, A.A. COVID-19 impact and survival strategy in business tourism market: The example of the UAE MICE industry. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2020, 7, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekgau, R.J.; Tichaawa, T.M. Adaptive strategies employed by the MICE sector in response to COVID-19. Geo J. Tour. Geosites 2021, 38, 1203–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragin-Jensen, C.; Kwiatkowski, G.; Lien, V.H.; Ossowska, L.; Janiszewska, D.; Kloskowski, D.; Strzelecka, M. Event innovation in times of uncertainty. Int. J. Event. Festiv. Manag. 2022, 13, 387–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukovska, G.; Mezgaile, A.; Klepers, A. The pressure of technological innovations in meeting and event industry under the COVID-19 influence. In Proceedings of the 13th International Scientific and Practical Conference on Environment, Technology and Resources 2021, Rezekne, Latvia, 17–18 June 2021; pp. 44–50. [Google Scholar]

- Mohanty, P.; Choudhury, R. Events tourism in the eye of the COVID-19 storm: Impacts and implications. In Event Tourism in Asian Countries; Apple Academic Press: Palm Bay, FL, USA, 2022; pp. 97–114. [Google Scholar]

- Zutshi, A.; Mendy, J.; Sharma, G.D.; Thomas, A.; Sarker, T. From challenges to creativity: Enhancing SMEs’ resilience in the context of COVID-19. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, T.; Wynn-Moylan, P. Conferences and Conventions: A Global Industry; Routledge: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bladen, C.; Kennell, J.; Abson, E.; Wilde, N. Events Management: An Introduction; Routledge: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hooshmand, R.; Sung, B.; Jefferies, K.; Jefferies, R.; Lin, J. The impact of COVID-19 on regional event attendees’ attitudes: A survey during and after COVID-19 lockdowns. Int. J. Event. Festiv. Manag. 2023, 14, 73–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E.; Smith, J.W. The spatial and temporal resilience of the tourism and outdoor recreation industries in the United States throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. Tour. Manag. 2023, 95, 104661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khlystova, O.; Kalyuzhnova, Y.; Belitski, M. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the creative industries: A literature review and future research agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 139, 1192–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orthodoxou, D.L.; Loizidou, X.I.; Gavriel, A.; Hadjiprocopiou, S.; Petsa, D.; Demetriou, K. Sustainable business events: The perceptions of service providers, attendees, and stakeholders in decision-making positions. J. Conv. Event Tour. 2022, 23, 154–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, K.; Junek, O.; Wang, C. Event management skills in the post-COVID-19 world: Insights from China, Germany, and Australia. Event. Manag. 2022, 26, 867–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilian, R.; Matschinger, H.; Loffler, W.; Roick, C.; Angermeyer, M.C. A comparison of methods to handle skew distributed cost variables in the analysis of the resource consumption in schizophrenia treatment. J. Ment. Health Policy Econ. 2002, 5, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.M.; Han, J.; Jiang, S. The impact of comment history disclosure on online comment posting behaviors. Inf. Technol. People 2023, 36, 2847–2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garthwaite, C.L. Demand spillovers, combative advertising, and celebrity endorsements. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 2014, 6, 76–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H.; Wang, D.; Desouza, K.C.; Evans, R. Digital transformation and the new normal in China: How can enterprises use digital technologies to respond to COVID-19? Sustainability 2021, 13, 10195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. A dynamic capabilities-based entrepreneurial theory of the multinational enterprise. In The Eclectic Paradigm: A Framework for Synthesizing and Comparing Theories of International Business from Different Disciplines or Perspectives; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 224–273. [Google Scholar]

- Neumannová, M. Smart districts: New phenomenon in sustainable urban development Case Study of Špitálka in Brno, Czech Republic. Folia Geogr. 2022, 64, 27–48. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).