Analyzing the Impact of Social Media Influencers on Consumer Shopping Behavior: Empirical Evidence from Pakistan

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Background

2.1. Social Influence Theory

2.2. Social Media Influencers

2.3. Brand Credibility

2.4. Shopping Values

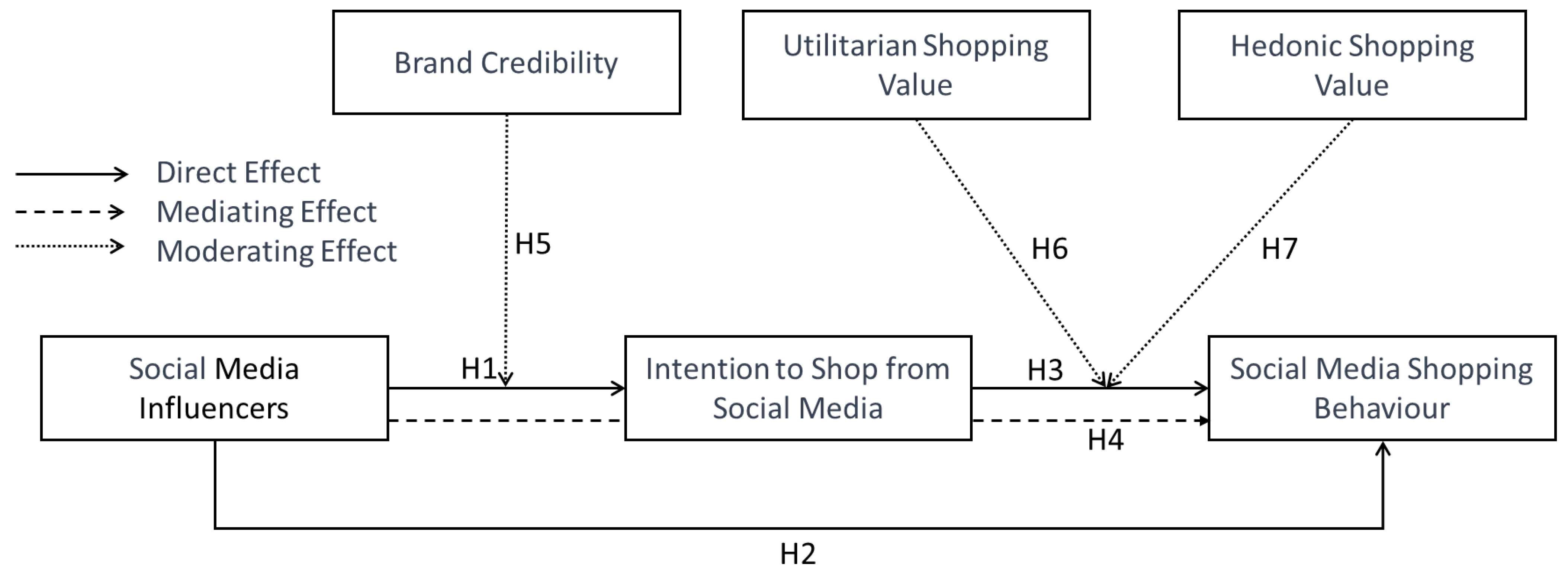

3. Research Framework and Hypothesis Development

3.1. Research Framework

3.2. Hypothesis Development

3.2.1. Social Media Influencers, Shopping Intention, and Shopping Behavior

3.2.2. Brand Credibility, Social Media Influencers, and Shopping Intention

3.2.3. Shopping Intention, Shopping Values, and Shopping Behavior

4. Methodology

4.1. Sample and Data Collection

4.2. Demographic Information on Respondents

4.3. Measures

| Constructs and Source | Items |

|---|---|

| Social Media Influencers (SMI) Ki et al. Pangarkar et al. [1,72] | SMI1. [SMIs] inspire me to discover something new about fashion products from social media. SMI2. [SMIs] have tastes and preferences similar to mine regarding fashion products. SMI3. [SMIs] seem to have a lot in common with me regarding fashion products. SMI4. [SMIs] are knowledgeable regarding fashion products. SMI5. [SMIs] make me feel like a mirror image of the person I would like to be through wearing similar fashion products. SMI6. [SMIs] make me feel the kind of person I want to be in life by making me wear similar fashion products. SMI7. [SMIs] make me feel a personal connection toward them through wearing similar fashion products. SMI8. [SMIs] make me feel an emotional connection toward them through wearing similar fashion products. SMI9. I would likely consider buying one of the same fashion products and brands the [SMIs] posted on their social media. SMI10. I would likely consider using one of the same fashion products and brands the [SMIs] posted on their social media. |

| Intention to Shop through Social Media (ISSM) Ajzen & Fishbein. Bian & Forsythe. Dodds et al. Patel et al. [10,39,73,74] | ISSM1. I would love to buy fashion products from social media. ISSM2. I will buy fashion products from social media in the future. ISSM3. I intend to buy fashion products from social media within the next year. ISSM4. There is a high probability that I would buy fashion products from social media within 6 months. |

| Social Media Shopping Behavior (SMSB) Lin. Patel et al. [10,75] | SMSB1. I prefer buying fashion products from social media. SMSB2. I frequently use social media to buy fashion products. SMSB3. On a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree), please indicate your agreement with the statement: ‘I am a frequent buyer of fashion products from social media.’ SMSB4. On a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree), please indicate your agreement with the statement: ‘I frequently purchase fashion products based on recommendations from Social Media Influencers.’ SMSB5. On a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree), please indicate your agreement with the statement: ‘I believe the role of brand reputation in my decision to purchase fashion products is very significant.’ |

| Brand Credibility (BC) Erdem et al. Guo & Luo. [21,49] | BC1. The brands shown on social media can’t deliver on their promises. BC2. The brands’ claims shown on social media are believable. BC3. The brands shown on social media deliver what they promise. BC4. The brands shown on social media are reliable. |

| Utilitarian Shopping Value (USV) De-hu, Hanafiza-deh et al. Qu et al. [22,76,77] | USV1. I think the products recommended by the social media platform or social media influencers are of good quality and trustworthy. USV2. I think the social media platform or social media influencers helped me choose the right product, which is a good bargain. USV3. I think the interactive features set by the platform are attractive and exactly what I want. |

| Hedonic Shopping Value (HSV) De-hu, Hanafizadeh et al. Qu et al. [22,76,77] | HSV1. Browsing through social media platforms when I’m bored makes me happy. HSV2. It’s fun to browse, express opinions, discuss, and communicate with other users on social media platforms. HSV3. Participating in topic comments and other activities on the social media platform makes me feel relaxed and happy. |

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Analytical Strategy and Descriptive Statistics

5.2. Reliability, Validity, and Collinearity

5.3. Structural Model Evaluation and Hypothesis Testing

5.4. The Explanatory and Predictive Power of the Model

6. From Theoretical Insights to Applicable Contributions

6.1. Theoretical Insights

6.2. Practical and Managerial Contributions

7. Limitations and Future Research

7.1. Limitations

7.2. Future Research

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pangarkar, A.; Patel, J.; Kumar, S.K. Drivers of EWOM Engagement on Social Media for Luxury Consumers: Analysis, Implications, and Future Research Directions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 74, 103410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangarkar, A.; Rathee, S. The Role of Conspicuity: Impact of Social Influencers on Purchase Decisions of Luxury Consumers. Int. J. Advert. 2023, 42, 1150–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meaghan Yuen Guide to Social Commerce and the Evolving Path to Purchase. Available online: https://www.emarketer.com/insights/social-commerce-brand-trends-marketing-strategies/ (accessed on 29 June 2024).

- Chris Dawson TikTok Shop Expands UK Shopify Integration. Available online: https://channelx.world/2024/03/tiktok-shop-expands-uk-shopify-integration/ (accessed on 29 June 2024).

- Statista. Influencer Advertising—Worldwide; Statista: Hamburg, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, A.A.; Mishra, A.S.; Vaishnav, K. Response to Social Media Influencers: Consumer Dispositions as Drivers. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2023, 47, 1979–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooi, K.B.; Lee, V.H.; Hew, J.J.; Leong, L.Y.; Tan, G.W.H.; Lim, A.F. Social Media Influencers: An Effective Marketing Approach? J. Bus. Res. 2023, 160, 113773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, T.; Nettleship, H.; Pinto, L.H. Judging a Book by Its Cover? The Role of Unconventional Appearance on Social Media Influencers Effectiveness. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 66, 102917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley Publishing Co., Inc.: Boston, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, A.K.; Singh, A.; Rana, N.P.; Parayitam, S.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Dutot, V. Assessing Customers’ Attitude towards Online Apparel Shopping: A Three-Way Interaction Model. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 164, 113917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwar, A.; Huang, Y.-C. Exploring the Impact of Social Media Influencers on Customers’ Purchase Intention: A Sequential Mediation Model in Taiwan Context. Entrep. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2022, 10, 123–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audrezet, A.; de Kerviler, G.; Guidry Moulard, J. Authenticity under Threat: When Social Media Influencers Need to Go beyond Self-Presentation. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koay, K.Y.; Lim, W.M.; Kaur, S.; Soh, K.; Poon, W.C. How and When Social Media Influencers’ Intimate Self-Disclosure Fosters Purchase Intentions: The Roles of Congruency and Parasocial Relationships. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2023, 41, 790–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kareem, S.A.; Venugopal, P. Social Media Influencers’ Traits and Purchase Intention: A Moderated Mediation Effect of Attitude towards Brand Credibility and Brand Familiarity. FIIB Bus. Rev. 2023, 231971452311622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ki, C.W.; Kim, Y.K. The Mechanism by Which Social Media Influencers Persuade Consumers: The Role of Consumers’ Desire to Mimic. Psychol. Mark. 2019, 36, 905–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Castillo, D.; Sánchez-Fernández, R. The Role of Digital Influencers in Brand Recommendation: Examining Their Impact on Engagement, Expected Value and Purchase Intention. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 49, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhukya, R.; Paul, J. Social Influence Research in Consumer Behavior: What We Learned and What We Need to Learn?—A Hybrid Systematic Literature Review. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 162, 113870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, W.; Oh, G.E.; Cho, H. Impact of COVID-19 on Consumers’ Impulse Buying Behavior of Fitness Products: A Moderated Mediation Model. J. Consum. Behav. 2022, 21, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallego, J.S.R.; Torres, J.A.S.; Irurita, A.A.; Cañada, F.J.A. Are Social Media Influencers Effective An Analysis of Information Adoption by Followers. Int. J. Technol. Mark. 2023, 17, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelman, H.C. Compliance, Identification, and Internalization Three Processes of Attitude Change. J. Confl. Resolut. 1958, 2, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Luo, Q. Investigating the Impact of Intelligent Personal Assistants on the Purchase Intentions of Generation Z Consumers: The Moderating Role of Brand Credibility. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 73, 103353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Cieślik, A.; Fang, S.; Qing, Y. The Role of Online Interaction in User Stickiness of Social Commerce: The Shopping Value Perspective. Digit. Bus. 2023, 3, 100061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, R.; Paul, J.; Koles, B. The Role of Brand Experience, Brand Resonance and Brand Trust in Luxury Consumption. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 66, 102895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamim, K.; Azam, M.; Islam, T. How Do Social Media Influencers Induce the Urge to Buy Impulsively? Social Commerce Context. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 77, 103621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuhaiber, A.; Al-Kfairy, M.; Alrabaee, S. The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly About Insta Shopping: A Qualitative Study. IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst. 2023, 10, 2786–2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelman, H.C. Processes of Opinion Change*. Public Opin. Q. 1961, 25, 57–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiese, M.; Martínez-Climent, C.; Botella-Carrubi, D. A Framework for Facebook Advertising Effectiveness: A Behavioral Perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 109, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tata, S.V.; Prashar, S.; Gupta, S. An Examination of the Role of Review Valence and Review Source in Varying Consumption Contexts on Purchase Decision. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 52, 101734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Lee, H. Do Parasocial Interactions and Vicarious Experiences in the Beauty YouTube Channels Promote Consumer Purchase Intention? Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2022, 46, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asch, S.E. Effects of Group Pressure upon the Modification and Distortion of Judgments. In Groups, Leadership and Men; Research in Human Relations; Carnegie Press: Oxford, UK, 1951; pp. 177–190. [Google Scholar]

- Milgram, S. Behavioral Study of Obedience. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 1963, 67, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashraf, A.; Hameed, I.; Saeed, S.A. How Do Social Media Influencers Inspire Consumers’ Purchase Decisions? The Mediating Role of Parasocial Relationships. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2023, 47, 1416–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridges, E.; Florsheim, R. Hedonic and Utilitarian Shopping Goals: The Online Experience. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I.A.; Alrawad, M.; Lutfi, A.; Azazz, A.M.S. Social Commerce and Buying Intention Post COVID-19: Evidence from a Hybrid Approach Based on SEM—FsQCA. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 76, 103548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kfairy, M.; Shuhaiber, A.; Al-Khatib, A.W.; Alrabaee, S. Social Commerce Adoption Model Based on Usability, Perceived Risks, and Institutional Trust. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2024, 71, 3599–3612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. From Intentions to Actions: A Theory of Planned Behavior. In Action Control: From Cognition to Behavior; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985; pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Vrontis, D.; Makrides, A.; Christofi, M.; Thrassou, A. Social Media Influencer Marketing: A Systematic Review, Integrative Framework and Future Research Agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 45, 617–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behaviour; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, UK, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.J.; Lin, L.M. Exploring Attitude–Behavior Gap in Sustainable Consumption: Comparison of Recycled and Upcycled Fashion Products. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 623–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, C.; Zeng, X.; Liang, S.; Zhang, K. Do Live Streaming and Online Consumer Reviews Jointly Affect Purchase Intention? Sustainability 2023, 15, 6992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhu, D.H. Effect of Dynamic Promotion Display on Purchase Intention: The Moderating Role of Involvement. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 148, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde, R.; Casais, B. Micro, Macro and Mega-Influencers on Instagram: The Power of Persuasion via the Parasocial Relationship. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 158, 113708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubb, C.; Colliander, J. “This Is Not Sponsored Content”—The Effects of Impartiality Disclosure and e-Commerce Landing Pages on Consumer Responses to Social Media Influencer Posts. Comput. Human Behav. 2019, 98, 210–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoenberger, H.; Kim, E. Explaining Purchase Intent via Expressed Reasons to Follow an Influencer, Perceived Homophily, and Perceived Authenticity. Int. J. Advert. 2023, 42, 368–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, C.; Yuan, S. Influencer Marketing: How Message Value and Credibility Affect Consumer Trust of Branded Content on Social Media. J. Interact. Advert. 2019, 19, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trudel, R. Sustainable Consumer Behavior. Consum. Psychol. Rev. 2019, 2, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otterbring, T.; Folwarczny, M. Social Validation, Reciprocation, and Sustainable Orientation: Cultivating “Clean” Codes of Conduct through Social Influence. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 76, 103612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdem, T.; Swait, J. Brand Credibility, Brand Consideration, and Choice. J. Consum. Res. 2004, 31, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, S.I.N.W.; Ali, S.F.S.; Teng, P.K. Love, Trust and Follow Them? The Role of Social Media Influencers on Luxury Cosmetics Brands’ Purchase Intention among Malaysian Urban Women. Malays. J. Consum. Fam. Econ. 2023, 30, 271–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teresa Borges-Tiago, M.; Santiago, J.; Tiago, F. Mega or Macro Social Media Influencers: Who Endorses Brands Better? J. Bus. Res. 2023, 157, 113606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrwashdeh, M.; Ali, H.; Helalat, A.; Alkhodary, D.A.A. The Mediating Role of Brand Credibility between Social Media Influencers and Patronage Intentions. Int. J. Data Netw. Sci. 2022, 6, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babin, B.J.; Darden, W.R.; Griffin, M. Work and/or Fun: Measuring Hedonic and Utilitarian Shopping Value. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 20, 644–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.A.; Wang, X.; Yang, Y. Sustainable Apparel Consumption: Personal Norms, CSR Expectations, and Hedonic vs. Utilitarian Shopping Value. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschman, E.C.; Holbrook, M.B. Hedonic Consumption: Emerging Concepts, Methods and Propositions. J. Mark. 1982, 46, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, S.; Banerjee, R.; Dagar, V. Analysis of Impulse Buying Behaviour of Consumer during COVID-19: An Empirical Study. Millenn. Asia 2023, 14, 278–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, K.E.; Spangenberg, E.R.; Grohmann, B. Measuring the Hedonic and Utilitarian Dimensions of Consumer Attitude. J. Mark. Res. 2003, 40, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.A.; Reynolds, K.E.; Arnold, M.J. Hedonic and Utilitarian Shopping Value: Investigating Differential Effects on Retail Outcomes. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 974–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, E.M. Justification Effects on Consumer Choice of Hedonic and Utilitarian Goods. J. Mark. Res. 2005, 42, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suparno, C. Online Purchase Intention of Halal Cosmetics: S-O-R Framework Application. J. Islam. Mark. 2020, 12, 1665–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.J.; Oh, K.W.; Kim, H.M. Country Differences in Determinants of Behavioral Intention towards Sustainable Apparel Products. Sustainability 2021, 13, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moharana, T.R.; Pattanaik, S. Post-Pandemic Revisit Intentions: How Shopping Value and Visit Frequency Matters. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2023, 51, 386–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overby, J.W.; Lee, E.-J. The Effects of Utilitarian and Hedonic Online Shopping Value on Consumer Preference and Intentions. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 1160–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y.-S. Hedonic and Utilitarian Shopping Values in Airport Shopping Behavior. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2015, 49, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayburn, S.W.; Anderson, S.T.; Zank, G.M.; McDonald, I. M-Atmospherics: From the Physical to the Digital. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 64, 102782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H.; Lee, H.N.; Choi, J.I. The Influence of Characteristics of Mobile Live Commerce on Purchase Intention. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, G. Regulatory Focus as a Moderator of Retail Shopping Behaviour. J. Strateg. Mark. 2016, 24, 484–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DataReportal. Digital 2024: Pakistan. Available online: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2024-pakistan (accessed on 28 June 2024).

- Hoyle, R.H. (Ed.) Handbook of Structural Equation Modeling; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-1-60623-077-0. [Google Scholar]

- Garland, R. The Mid-Point on a Rating Scale: Is It Desirable? Mark. Bull. 1991, 2, 66–70. [Google Scholar]

- Behling, O.; Law, K.S. Translating Questionnaires and Other Research Instruments: Problems and Solutions; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000; Volume 133. [Google Scholar]

- Ki, C.W.; Cuevas, L.M.; Chong, S.M.; Lim, H. Influencer Marketing: Social Media Influencers as Human Brands Attaching to Followers and Yielding Positive Marketing Results by Fulfilling Needs. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 55, 102133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, W.B.; Monroe, K.B.; Grewal, D. Effects of Price, Brand, and Store Information on Buyers’ Product Evaluations. J. Mark. Res. 1991, 28, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Q.; Forsythe, S. Purchase Intention for Luxury Brands: A Cross Cultural Comparison. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1443–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.F. Predicting Consumer Intentions to Shop Online: An Empirical Test of Competing Theories. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2007, 6, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.H.; Han, X.Y.; Li, Y.Z. Factors Affecting Consumers’ Purchase Intention in Electronic Commerce of Fresh Agro-Products. J. Northwest AF Univ. 2014, 14, 85–91. [Google Scholar]

- Hanafizadeh, P.; Shafia, S.; Bohlin, E. Exploring the Consequence of Social Media Usage on Firm Performance. Digit. Bus. 2021, 1, 100013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, M.; Asare, C.; Fatawu, A.; Abubakari, A. An Analysis of the Effects of Customer Satisfaction and Engagement on Social Media on Repurchase Intention in the Hospitality Industry. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2022, 9, 2028331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, S.; Khadim, S.; Ali Asadullah, M.; Syed, N. Exploring the Influence of Artificial Intelligence Technology on Consumer Repurchase Intention: The Mediation and Moderation Approach. Technol. Soc. 2023, 72, 102190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Matthews, L.M.; Ringle, C.M. Identifying and Treating Unobserved Heterogeneity with FIMIX-PLS: Part I—Method. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2016, 28, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorndike, R.M. Book Review: Psychometric Theory (3rd Ed.) by Jum Nunnally and Ira Bernstein New York: McGraw-Hill, 1994, Xxiv + 752 pp. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1995, 19, 303–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, G.; Sarstedt, M. Heuristics versus Statistics in Discriminant Validity Testing: A Comparison of Four Procedures. Internet Res. 2019, 29, 430–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, M.N.K.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research Methods for Business Students, 7th ed.; SE—XXVI; Pearson Education Limited: London, UK, 2016; 741p, ISBN 9781292016627. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Wang, S. Factors Influencing the Purchase Intention for Online Health Popular Science Information Based on the Health Belief Model. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Measure | Category | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 19 years and below | 103 | 10.42 |

| 20–29 years | 308 | 31.17 | |

| 30–39 years | 213 | 21.56 | |

| 40–49 years | 136 | 13.77 | |

| 50–59 years | 105 | 10.63 | |

| 60+ years | 123 | 12. 45 | |

| Household Income | PKR 20,000 to 60,000 | 378 | 38.26 |

| PKR 60,000 to 100,000 | 272 | 27.53 | |

| PKR 100,000 to 150,000 | 162 | 16.40 | |

| Greater than PKR 150,000 | 176 | 17.81 | |

| Gender | Male | 476 | 48.18 |

| Female | 512 | 51.82 | |

| Education | Below High School | 101 | 10.22 |

| High School | 209 | 21.16 | |

| College Education | 256 | 25.91 | |

| University Degree | 422 | 42.71 | |

| Occupation | Employee/Business | 512 | 51.83 |

| Students | 365 | 36.94 | |

| Unemployed | 111 | 11.23 |

| Name | Items | Mean | Median | Standard Deviation | Excess Kurtosis | Skewness | Factor Loading |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Media Influencers | SMI1 | 3.403 | 4 | 1.652 | −1.231 | −0.113 | 0.748 |

| SMI2 | 3.428 | 4 | 1.492 | −1.014 | −0.132 | 0.853 | |

| SMI3 | 3.38 | 4 | 1.471 | −0.973 | −0.065 | 0.837 | |

| SMI4 | 3.818 | 4 | 1.426 | −0.67 | −0.422 | 0.741 | |

| SMI5 | 3.315 | 3 | 1.593 | −1.179 | 0.006 | 0.879 | |

| SMI6 | 3.266 | 3 | 1.572 | −1.167 | 0.02 | 0.875 | |

| SMI7 | 3.225 | 3 | 1.567 | −1.133 | 0.081 | 0.881 | |

| SMI8 | 3.107 | 3 | 1.557 | −1.111 | 0.179 | 0.86 | |

| SMI9 | 3.439 | 4 | 1.57 | −1.13 | −0.106 | 0.841 | |

| SMI10 | 3.442 | 4 | 1.54 | −1.08 | −0.108 | 0.832 | |

| Intention to Shop through Social Media | ISSM1 | 4.206 | 4 | 1.352 | 0.046 | −0.827 | 0.883 |

| ISSM2 | 4.418 | 5 | 1.308 | 0.581 | −1.004 | 0.899 | |

| ISSM3 | 4.32 | 5 | 1.382 | 0.149 | −0.927 | 0.915 | |

| ISSM4 | 4.16 | 4 | 1.433 | −0.322 | −0.698 | 0.886 | |

| Social Media Shopping Behavior | SMSB1 | 3.93 | 4 | 1.467 | −0.737 | −0.472 | 0.872 |

| SMSB2 | 3.907 | 4 | 1.53 | −0.944 | −0.412 | 0.876 | |

| SMSB3 | 3.492 | 4 | 1.621 | −1.143 | −0.133 | 0.839 | |

| SMSB4 | 3.238 | 3 | 1.623 | −1.189 | 0.04 | 0.764 | |

| SMSB5 | 4.59 | 5 | 1.515 | 0.086 | −1.035 | 0.558 | |

| Utilitarian Shopping Value | USV1 | 3.698 | 4 | 1.357 | −0.624 | −0.363 | 0.894 |

| USV2 | 3.671 | 4 | 1.406 | −0.702 | −0.352 | 0.921 | |

| USV3 | 3.761 | 4 | 1.344 | −0.549 | −0.393 | 0.882 | |

| Hedonic Shopping Value | HSV1 | 4.315 | 5 | 1.337 | 0.179 | −0.828 | 0.86 |

| HSV2 | 4.106 | 4 | 1.385 | −0.373 | −0.612 | 0.902 | |

| HSV3 | 3.757 | 4 | 1.483 | −0.852 | −0.298 | 0.866 | |

| Brand Credibility | BC1 | 3.794 | 4 | 1.356 | −0.71 | −0.209 | 0.188 |

| BC2 | 3.781 | 4 | 1.342 | −0.583 | −0.307 | 0.899 | |

| BC3 | 3.741 | 4 | 1.362 | −0.57 | −0.324 | 0.914 | |

| BC4 | 3.793 | 4 | 1.326 | −0.476 | −0.392 | 0.916 |

| Construct | α | rho_a | rho_c | AVE | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Media Influencers (SMI) | 0.899 | 0.902 | 0.937 | 0.832 | 0.899 |

| Intention to Shop through Social Media (ISSM) | 0.918 | 0.918 | 0.942 | 0.802 | 0.918 |

| Social Media Shopping Behavior (SMSB) | 0.845 | 0.878 | 0.891 | 0.625 | 0.845 |

| Brand Credibility (BC) | 0.899 | 0.902 | 0.937 | 0.832 | 0.899 |

| Utilitarian Shopping Value (USV) | 0.882 | 0.882 | 0.927 | 0.809 | 0.882 |

| Hedonic Shopping Value (HSV) | 0.848 | 0.849 | 0.908 | 0.767 | 0.848 |

| SMI | ISSM | SMSB | BC | USV | HSV | SMI | ISSM | SMSB | BC | USV | HSV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMI | 0.836 | |||||||||||

| ISSM | 0.510 | 0.479 | 0.896 | |||||||||

| SMSB | 0.637 | 0.869 | 0.581 | 0.783 | 0.791 | |||||||

| BC | 0.607 | 0.608 | 0.663 | 0.561 | 0.554 | 0.588 | 0.912 | |||||

| USV | 0.777 | 0.626 | 0.690 | 0.777 | 0.713 | 0.565 | 0.602 | 0.692 | 0.899 | |||

| HSV | 0.599 | 0.497 | 0.500 | 0.554 | 0.641 | 0.537 | 0.440 | 0.427 | 0.484 | 0.556 | 0.876 |

| Saturated Model | Estimated Model | |

|---|---|---|

| SRMR | 0.053 | 0.058 |

| d_ULS | 1.235 | 1.465 |

| d_G | 0.55 | 0.562 |

| Chi-square | 3135.307 | 3192.884 |

| NFI | 0.867 | 0.864 |

| Relationship | β | SD | T | p | LLCI | ULCI | Hypothesis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMI -> ISSM | 0.257 | 0.034 | 7.629 | 0.000 | 0.195 | 0.327 | H1 Accepted |

| SMI -> SMSB | 0.210 | 0.038 | 10.071 | 0.000 | 0.15 | 0.276 | H2 Accepted |

| ISSM -> SMSB | 0.652 | 0.023 | 28.076 | 0.000 | 0.605 | 0.696 | H3 Accepted |

| SMI -> ISSM -> SMSB | 0.171 | 0.022 | 7.762 | 0.000 | −0.127 | 0.214 | H4 Accepted |

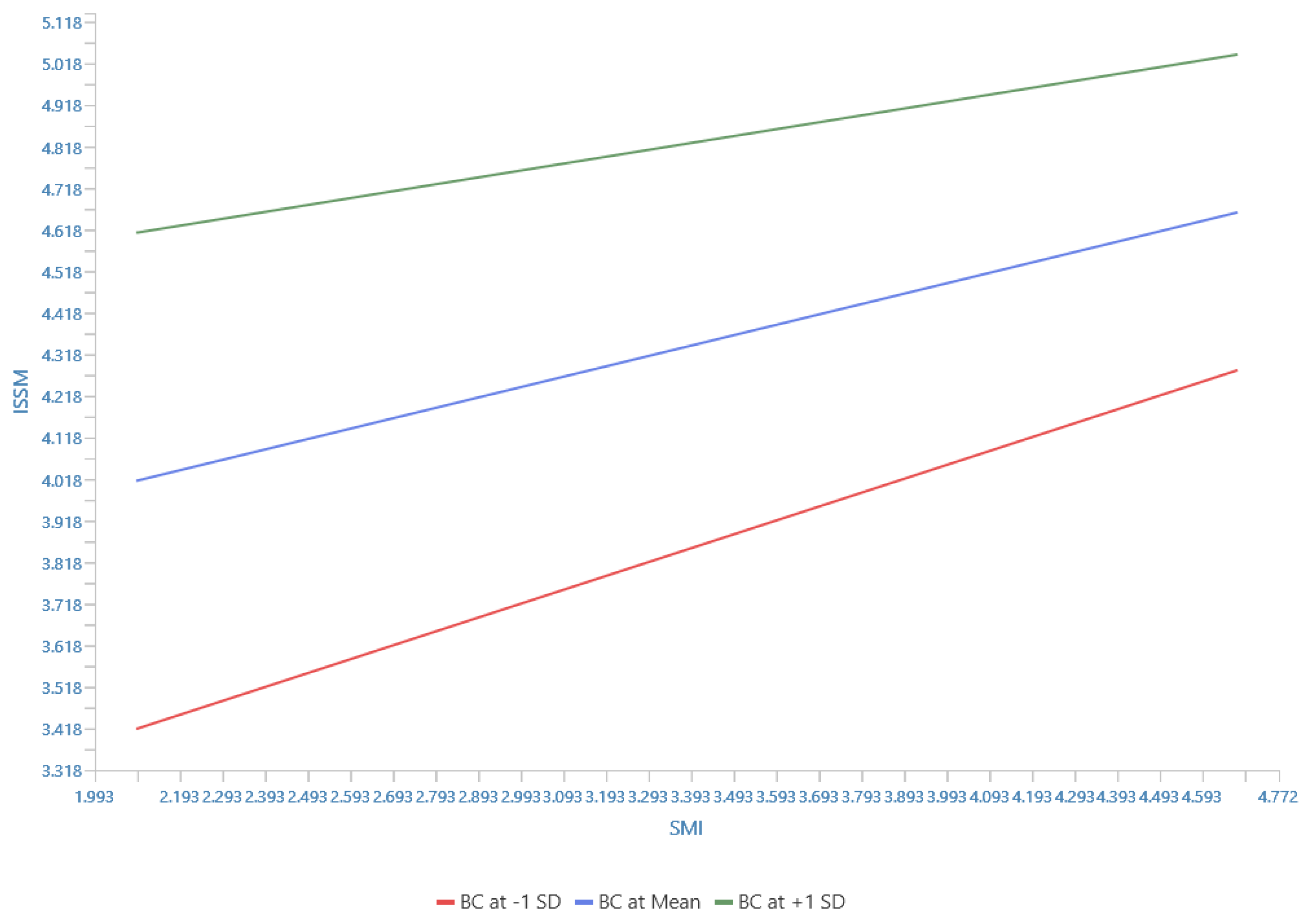

| BC × SMI -> ISSM | −0.088 | 0.027 | 3.447 | 0.002 | −0.141 | −0.03 | H5 Accepted |

| USV × ISSM -> SMSB | 0.045 | 0.017 | 1.104 | 0.010 | 0.011 | 0.078 | H6 Accepted |

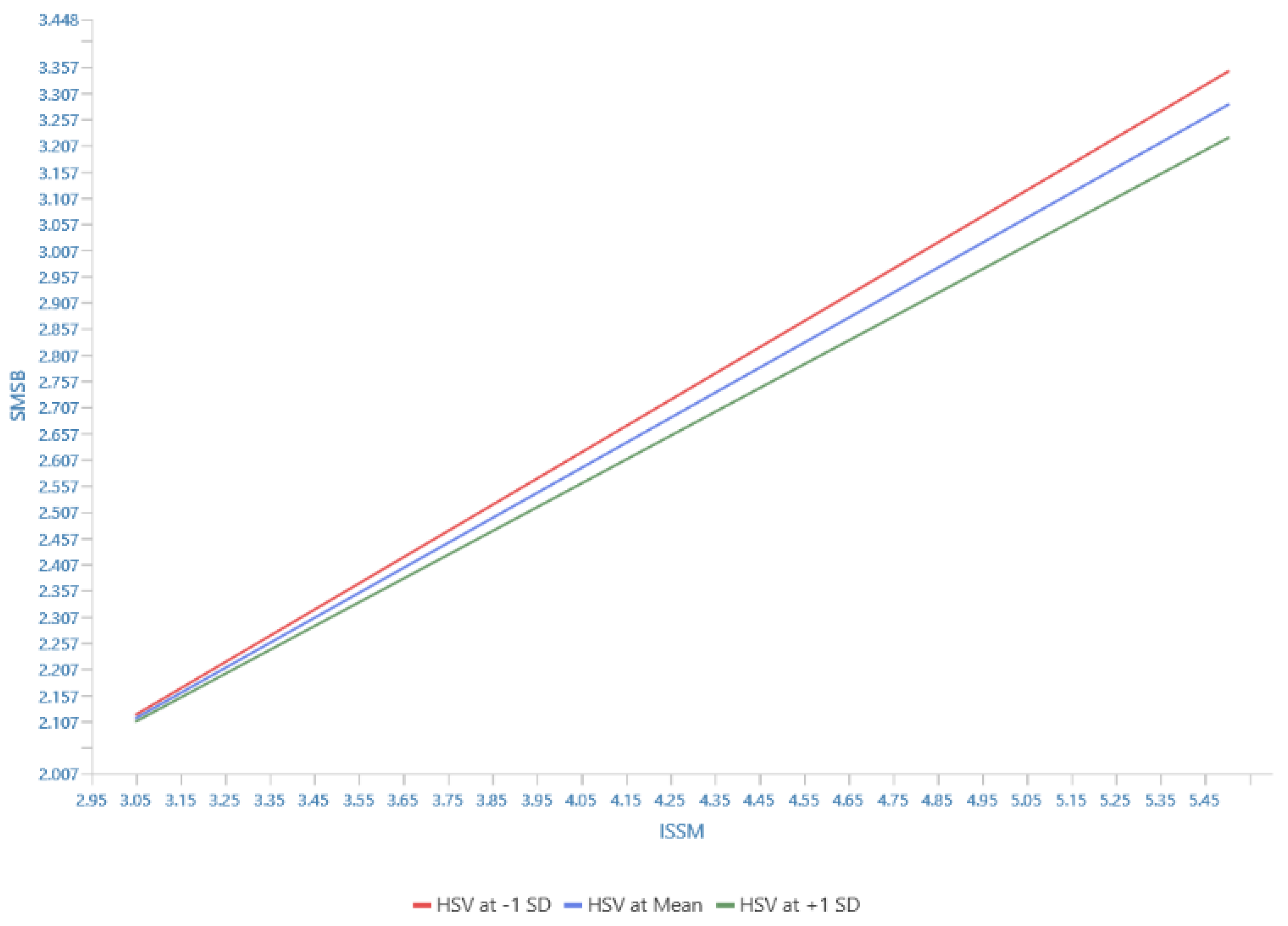

| HSV × ISSM -> SMSB | −0.018 | 0.017 | 2.587 | 0.270 | −0.051 | 0.013 | H7 Not Accepted |

| Endogenous Variables | R-Square | R-Square Adjusted | Q2-Predict |

|---|---|---|---|

| ISSM | 0.357 | 0.355 | 0.349 |

| SMSB | 0.679 | 0.677 | 0.435 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Afzal, B.; Wen, X.; Nazir, A.; Junaid, D.; Olarte Silva, L.J. Analyzing the Impact of Social Media Influencers on Consumer Shopping Behavior: Empirical Evidence from Pakistan. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6079. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16146079

Afzal B, Wen X, Nazir A, Junaid D, Olarte Silva LJ. Analyzing the Impact of Social Media Influencers on Consumer Shopping Behavior: Empirical Evidence from Pakistan. Sustainability. 2024; 16(14):6079. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16146079

Chicago/Turabian StyleAfzal, Bilal, Xiao Wen, Ahad Nazir, Danish Junaid, and Leidy Johanna Olarte Silva. 2024. "Analyzing the Impact of Social Media Influencers on Consumer Shopping Behavior: Empirical Evidence from Pakistan" Sustainability 16, no. 14: 6079. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16146079

APA StyleAfzal, B., Wen, X., Nazir, A., Junaid, D., & Olarte Silva, L. J. (2024). Analyzing the Impact of Social Media Influencers on Consumer Shopping Behavior: Empirical Evidence from Pakistan. Sustainability, 16(14), 6079. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16146079