Abstract

This study explores the development prospects of tourism in predominantly industrial small-sized cities (SSCs), focusing on the integration of tourism into urban planning and sustainable practices. Using structural equation modeling (SEM) to analyze survey data from SSCs in Serbia and Russia, the research identifies key factors contributing to urban tourism sustainability. The analysis reveals the significant roles of environmental, economic, social, and cultural indicators in promoting sustainable urban tourism. The importance of inclusive development and community engagement is also highlighted, underscoring their impact on sustainability. The findings offer theoretical insights and practical recommendations for effectively incorporating tourism into urban planning to achieve comprehensive sustainability in SSCs.

1. Introduction

Urban tourism fundamentally influences the dynamics of cities, from social and cultural to the economic perspective, especially those of small and medium size that are primarily industry-oriented [1]. In this context, exploring the possibilities for developing sustainable urban tourism becomes crucial for their broader expansion and transformation. Despite significant interest in urban tourism, there is a noticeable lack of detailed research addressing how to achieve sustainability in such cities [2]. In most cases, traditional industrial cities either do not invest in tourism development or try to develop industrial heritage tourism as a specific form of tourism [3].

The gap in the scholarly literature requires detailed attention due to the potential long-term benefits that sustainable urban tourism can provide to local communities in SSCs. The study aims to thoroughly examine how current practices and strategies in urban tourism can be realigned and adapted to the sustainable doctrines, especially in predominantly industrial environments. The innovation of the study stems from an integrative approach that combines aspects of urban planning with sustainable practices and active community participation. This approach enables the exploration of the prospective of urban tourism to support the achievement of global goals of sustainable policies through increased environmental conservation, social equality, and cultural enrichment. The following questions form the basis of this research:

Q1: How does the implementation of sustainable tourism practices affect diverse sustainable features (social, economic, environmental, and cultural) in SSCs?

Q2: What are the effects of integrating tourism into urban planning processes on the sustainable outcomes of urban tourism?

Q3: How can inclusive development and local residents’ engagement in SSCs enhance the positive effects of sustainable urban tourism?

Q4: Which specific strategies for overcoming industrial constraints and industrial heritage can enable the successful integration of sustainable tourism in predominantly industrial SSCs?

The objectives of this research include not only the identification and evaluation of sustainable tourism practices that contribute to urban sustainable solutions in the selected two SSCs but also the development of new methodological approaches for analyzing and implementing these transforming practices in small industrial cities. Additionally, this work aims to demonstrate how inclusive development models can effectively address and enhance the social and economic benefits of urban tourism, offering new perspectives for local and national policies. This study is not only an opportunity for theoretical contribution but also provides practical guidelines for creating policies that can have broad positive effects on urban societies at a global level. With its multidisciplinary approach, the research represents an important step toward understanding the complex dynamics of sustainable growth for city tourism in mostly industrialized areas.

Although this study presents a comparative analysis of the integration of sustainable tourism in two countries with different industrial backgrounds, it is important to note that significant differences in national size, industrial base, and spatial geographical distribution exist between these countries. These distinctions must be considered when interpreting the results and their applicability to broader contexts.

2. Conceptual Background and Hypothesis Statements

2.1. Urban Tourism in Predominantly Industrial SSCs

Urban tourism, as defined by Mora and Bolici [4], is a significant component of the tourism industry, involving visits to urban centers and engaging in diverse tourist activities available throughout the year. This form of tourism operates in urban environments characterized by a non-agricultural economy encompassing administration, production, trade, services, and transportation hubs, as detailed by the UN Tourism [5] and further supported by Nicholls et al. [6] and Seto et al. [7]. The importance of urban tourism in stimulating economic growth in developing countries is highlighted through its roles in generating revenue, creating jobs, and enhancing infrastructure and international visibility [8,9,10,11]. The success of urban tourism relies significantly on the geographical uniqueness of cities. Vinyals-Mirabent [12] stressed the importance of having a geographical pattern that differs from typical metropolises, which is crucial for industrial cities where tourism is not the primary activity but integrated into their economic development plans. This uniqueness, which may include distinctive architectural styles or special cultural landmarks, not only attracts visitors but also aids in globalizing these destinations, thus allowing cities to offer unique experiences tailored to diverse individual preferences such as cultural events and local cuisine [13,14].

The development of urban tourism in predominantly SSCs presents a complex challenge that, according to Hidalgo [15], requires innovative approaches to align industrial capacities with the needs of the tourism sector. Industrial cities, traditionally focused on production, often face specific challenges such as pollution, a lack of attractive tourist locations, and infrastructural barriers, which according to Conelli [16], Bramwell and Lane [17] and Guzman [18] can complicate the development of tourism. Tosun [19] highlighted that the key to success in transforming these cities lies in engaging local communities and aligning tourism initiatives with existing industrial activities. Edwards, Griffin and Hayllar [20] as well as Loach [21] emphasized that the integration of tourism into urban planning should be strategically directed to improve infrastructure and enhance the quality of life for the local population.

According to the classification of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) [22], cities are classified as small-sized if they have a population between 40,000 and 200,000. This indicator is measured as a percentage of the national population. Large numbers of these SSCs, which were formerly dominated by industrial development, are now shifting toward a service-oriented economy and opening up to the tourist sector in an effort to promote sustainable economic growth [23]. Even more, urban tourism in SSCs is becoming increasingly popular among new generations of tourists [24,25].

As the main research objective includes the identification and evaluation of sustainable tourism practices that contribute to urban sustainable solutions along with the development of new methodological approaches for analyzing and implementing these practices in SSCs, two carefully selected locations were tested. The term “predominantly industrial” in our study refers to SSCs where over 50% of economic output and employment are related to industrial sectors such as manufacturing, heavy machinery, and chemical production [22]. For this purpose, we selected two representative cases of predominantly industrial small urban areas. The first one is Zrenjanin in northern Serbia with a population of approximately 67,000 people [26]. The second location is Satka, a small town in Southern Ural Mountains of Russia, with a population of approximately 42,000 people [27]. Both Zrenjanin and Satka are typical industrial cities that, besides being centers of heavy and light industry, are also striving to develop urban tourism [28,29]. Comparing two cities with varying sizes and locations is intriguing because it provides insight into the characteristics of typical industrial sites that have recently been reoriented toward service-oriented development in two distinct emerging regions.

The first analyzed location, Zrenjanin, traditionally relies on the food industry, chemical industry, brewery, and machinery (manufacture of boilers for central heating and radiators, reparation of locomotives, railcars, and rail assemblies). Zrenjanin’s deindustrialization was finished in the early 21st century, having started in the 1990s. The collapse of the city’s industrial titans may be attributed to several factors, including the nation’s political unrest, economic decline from isolation and conflict, inadequate management, misuse of privatizations, and others [28]. The city generally deteriorated in terms of economy and society as a result of deindustrialization. The old industrial plants were ignored and left to decay, and now they serve as the foundation for industrial heritage, while the manufacturing was transferred to new factory halls on the outskirts of the city. These artifacts can be employed in the development of industrial heritage tourism, which in industrialized nations stimulates economic growth and aids in the preservation of regional identities [30,31]. On the other hand, the second observed location, Satka, is also an excellent illustration of how an industrial city can be methodically transformed into a hub for ecological and event tourism in addition to heavy industry. Historically, the city has been mostly centered on producing iron. There was the discovery of magnesite, which is a mineral used to make refractory brick for blast furnaces [32]. However, the primary industries of metallurgical facilities for the mining of magnesite and other ores have recently been replaced by the concept of urban creative-tourism development strongly supported by the newly established public enterprise. The closeness of the attractive South Urals and Zyuratkul National Park additionally contributed to visitors’ attention to the area. Even if it is not a typical de-industrialization process, it is more like the complementary spillover process initiated by the local public enterprise, which actively cooperates on tourism strategies with municipal authorities. The local institutions recognized the importance of the sustainable development of urban tourism and provide strong institutional support [29,33].

The comparative analysis between these two cities aims to highlight the different industrial contexts and their modern approaches to the integration of sustainable tourism. We examine the demographic, economic, and social characteristics of both cities to understand how these factors affect the development of sustainable urban tourism. The selected locations differ in terms of size, socioeconomic status, and cultural background, providing a rich comparative framework for analyzing different influences and strategies.

This study selected two countries (Serbia and Russia) to explore the unique challenges and opportunities faced by industrial cities in different geopolitical and economic contexts. Both countries have a similar history of industrial development as ex-communist systems, but they differ in their current developing socioeconomic trajectories and policies toward urban tourism. This selection allows us to draw insights and recommendations applicable to other industrial cities undergoing similar transitions around the world. Examples of two selected locations include promoting events that highlight local culture, such as festivals, exhibitions, and gastronomic events, and providing help to preserve and promote local identity and attract tourists, further supporting sustainable development [29,34]. In this respect, the approach to sustainable urban tourism proves to be a key strategy for industrial cities seeking to leverage their urban centers as engines of economic and sociocultural development while minimizing negative consequences [35,36].

2.2. Sustainability of Urban Tourism in SSCs

Sustainable urban tourism aims to preserve city heritage, strengthen local communities, and ensure long-term development and employment opportunities, as noted by D’Alençon and Morales [37]. This approach involves balancing the interests of residents and visitors in SSCs, minimizing environmental impacts and unsustainable consumption, as outlined by Postma and Schmuecker [38]. However, as Guo et al. [39] highlighted, overtourism presents a significant challenge, driven by mass tourism and affecting the environmental quality of urban tourist locations, such as air quality, which is often ignored by travelers. The efficiency of municipal services in managing tourism influx, particularly in transportation and sanitation, is crucial for sustainability, which is a point supported by Santos-Rojo et al. [40] who observe new research trends in overtourism primarily in European urban areas.

Panasiuk [41] emphasizes the need for municipal authorities to engage in proactive, long-term cooperation with all stakeholders of urban tourism in SSCs. Despite the wide acceptance of sustainable tourism among tourism managers and planners, Maxim [42] pointed out that even in the large city of London, only a few local authorities promote sustainability concepts in their policy documents, and even fewer implement these policies effectively. As he claimed, most of these initiatives are stand-alone activities that deal with only a subset of sustainable tourism issues. In line with these observations, Grah et al. [43] recommended prioritizing sustainability in the development of urban tourism, considering a broad range of sustainability elements and stakeholders. Their study finds that economic, social, and environmental sustainability are essential considerations with local communities and businesses frequently cited as key actors. Thus, sustainable urban tourism in SSCs not only demands effective governance, which includes strategic planning, education, and policymaking, but also requires a comprehensive approach that integrates the needs and welfare of all stakeholders to foster a resilient urban tourism sector.

While many authors highlight the financial priorities of the urban tourism growth, concerns persist about the rapid tourism expansion in predominantly industrial SSCs, as it can strain natural, cultural, and socioeconomic resources [44,45,46]. The rapid development often leads to overloaded infrastructure, an erosion of local identity and culture, and increased property prices and living costs, potentially sparking social tensions among residents [47,48,49]. In response, Łapko et al. [50] advocated for urgent strategies to balance urban tourism growth with the preservation of local communities’ quality of life.

This balancing act involves managing (dis-)advantages of urban tourism development in industrial SSCs, aiming to sustain it as an economically beneficial activity while also conserving social and natural values. Adiati et al. [51] emphasized the need for extensive planning and strategic decision making to preserve key ecological processes and cultural heritage, arguing that without such measures, urban tourism in predominantly industrial SSCs might degrade these resources even while generating economic gains. Further supporting sustainable approaches, Miller et al. [52], Koens et al. [53] and Niñerola et al. [54] advocated for the incorporation of green technologies and the promotion of local culture in tourism activities coupled with strong community engagement to mitigate environmental and sociocultural impacts. Additionally, Zamfir and Corbos [55], D’Amato et al. [56], and Wei et al. [57] stressed that sustainable urban tourism in industrial SSCs is essential for improving the local conditions of many urban areas. Aall and Koens [58] discussed the challenges in reconciling improvements in residents’ quality of life with tourism demands, noting the tension between local desires for high ecological standards and the pressures of overtourism. Despite these initiatives, critics like Chen et al. [59], Fistola et al. [60] and Dodds and Butler [61] argued that many sustainability measures are often superficial and fail to produce lasting results. They pointed out that although green technologies and sustainable practices are promising, they require significant initial investments that may not be feasible for all destinations, particularly in industrial cities. Moreover, Gowel et al. [62] and Grube [63] caution that using sustainable development as merely a marketing tool can lead to cynicism and resistance among local populations, undermining the genuine preservation of natural and cultural resources.

2.3. Hypothesis Setting

The challenges of developing urban tourism in industrial cities need to be carefully considered to ensure that efforts toward sustainable urban tourism are accompanied by concrete and measurable outcomes [64,65,66]. In light of these challenges, the quest for sustainable urban tourism represents a crucial moment where contemporary urban planning, environmental stewardship, and socioeconomic development converge [67,68,69,70]. This literature review spans various research domains to precisely delineate the key elements for this study: sustainable urban tourism practices (SUTPs), integration of tourism into urban planning (ITUP), inclusive development for citizens and visitors (IDCV), and the mediators: economic indicators (EIs), social indicators (SIs), environmental indicators (ENIs), and cultural indicators (CIs). Urban tourism is increasingly recognized as an essential component of city planning where a strategic approach is necessary to fully harness its potential [71]. The integration of tourism in urban planning (ITUP) ensures that tourism development is aligned with broader urban agendas, mitigating negative impacts and optimizing benefits for industrial cities [72,73]. This approach requires the implementation of governance models that foster collaboration among stakeholders, including local governments, tourism businesses, and community groups [43].

By promoting a harmonious integration of tourism with urban infrastructure and local culture, the ITUP aims to create a sustainable urban environment that benefits both residents and visitors. In light of the challenges and opportunities presented by the ITUP, several hypotheses have been formulated to explore its indirect effects on the long-term viability of urban tourism by various mediators. These hypotheses include the following:

H1a:

The incorporation of tourism into urban planning (ITUP) positively influences the long-term viability of urban tourism by cultural indicators (CIs).

H1b:

The incorporation of tourism into urban planning (ITUP) positively influences the long-term viability of urban tourism by economic indicators (EIs).

H1c:

The incorporation of tourism into urban planning (ITUP) positively influences the long-term viability of urban tourism by environmental indicators (ENIs).

H1d:

The incorporation of tourism into urban planning (ITUP) positively influences the long-term viability of urban tourism by social indicators (SIs).

Sustainable urban tourism practices (SUTPs) are crucial, particularly in industrial cities where balancing growth with environmental sustainability is highly sensitive. A significant body of research, including studies by Lalicic and Önder [74] and Cohen [75], has underscored the necessity of SUTP, focusing on resource efficiency, emissions reduction, and the conservation of local identity. These practices are vital not only for environmental protection but also for ensuring the sustainability of urban destinations [76,77]. In industrial cities, implementing sustainable practices such as eco-friendly infrastructure and responsible waste management not only contributes to the destination’s competitiveness and attractiveness but also addresses critical environmental pressures often exacerbated by rapid urbanization and tourism growth [43,78]. Given this context, the following hypotheses have been formulated:

H2a:

Sustainable urban tourism practices (SUTPs) positively influence the long-term viability of urban tourism by cultural indicators (CIs).

H2b:

Sustainable urban tourism practices (SUTPs) positively influence the long-term viability of urban tourism by economic indicators (EIs).

H2c:

Sustainable urban tourism practices (SUTPs) positively influence the long-term viability of urban tourism by environmental indicators (ENIs).

H2d:

Sustainable urban tourism practices (SUTPs) positively influence the long-term viability of urban tourism by social indicators (SIs).

Inclusive development for citizens and visitors (IDCV) plays a significant role in ensuring that tourism development benefits both local residents and visitors, especially in industrial cities where socioeconomic disparities are often pronounced. The emphasis on equitable benefit distribution and community engagement, as highlighted by Muler Gonzalez et al. [79], underscores the importance of fostering inclusive growth within tourism. Tourism initiatives should not only be accessible to all segments of society but also contribute to urban regeneration, cultural diversity, and social cohesion [80].

H3a:

Inclusive development for citizens and visitors (IDCV) positively influences the long-term viability of urban tourism by cultural indicators (CIs).

H3b:

Inclusive development for citizens and visitors (IDCV) positively influences the long-term viability of urban tourism by economic indicators (EIs).

H3c:

Inclusive development for citizens and visitors (IDCV) positively influences the long-term viability of urban tourism by environmental indicators (ENIs).

H3d:

Inclusive development for citizens and visitors (IDCV) positively influences the long-term viability of urban tourism by social indicators (SIs).

Economic sustainability in urban tourism is commonly evaluated using indicators such as job creation, income distribution, and local economic growth [81,82]. However, it is crucial to balance the economic benefits with the potential costs to the community and infrastructure [83]. This equilibrium ensures that urban tourism contributes positively to the local economy while mitigating any adverse effects on the community and its resources. Nesticò and Mastelli [84] argued that the economic vulnerability characteristic of urban environments underscores the necessity of including several sustainability factors in the procedures used to define strategies and investment initiatives in the travel industry. According to their research, economic sustainability indicators play a significant role in assessing and planning tourism investments, which is crucial for island states facing challenges specific to their unique territories.

H4:

Economic indicators (EIs) directly and positively influence the sustainability of urban tourism (SUT).

In industrial small and medium cities, social sustainability in tourism requires a comprehensive approach that considers factors such as quality of life, social equity, and the preservation of cultural heritage [85]. It is crucial to examine how tourism impacts urban social structures, community well-being, and access to social services [43,86]. By systematically addressing these social indicators, urban tourism stands to deliver a pivotal contribution to nurturing the collective well-being and solidarity of communities in developing nations, thereby advancing their sustainable development objectives.

H5:

Social indicators (SIs) directly and positively influence the sustainability of urban tourism (SUT).

Environmental indicators in urban tourism encompass biodiversity conservation, resource management, and pollution control [87,88,89], with the aim to reduce the ecological footprint of tourism activities while promoting environmental awareness [90,91,92]. Dieguez-Castrillón et al. [93] found that environmental indicators stand out in most cases as the main indicators, especially when it comes to sustainable urban tourism.

H6:

Environmental indicators (ENIs) directly and positively influence the sustainability of urban tourism (SUT).

Cultural sustainability involves protecting and promoting local heritage and traditions [94,95]. Urban tourism provides opportunities to showcase cultural assets, which must be carefully managed to prevent commodification and cultural erosion [86,96]. Cultural indicators serve as important tools for tourism managers, enabling them to analyze the state of destinations and identify issues that require improvement in the context of sustainable tourism activities [97,98,99].

H7:

Cultural indicators (CIs) directly and positively impact the sustainability of urban tourism (SUT).

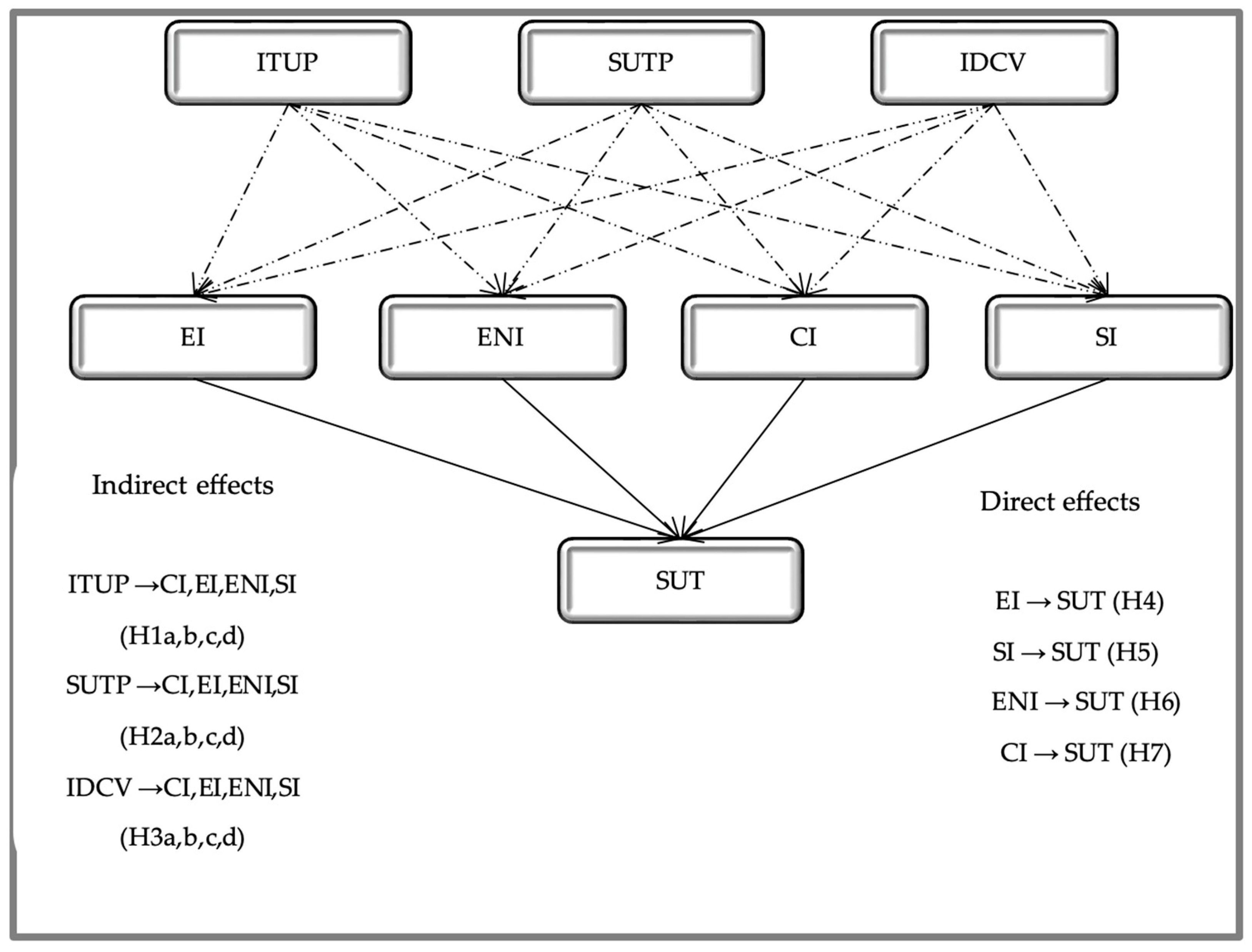

Figure 1 shows the proposed model, depicting the initial hypotheses related to the indirect effects of factors ITUP, SUTP, and IDCV (via mediators EIs, ENIs, SIs, CIs) and direct effects (EIs, ENIs, CIs, SIs) on the criterion variable sustainable urban tourism in small industrial cities.

Figure 1.

Proposed research model. Note: ITUP—integration of tourism in urban planning; SUTP—sustainable urban tourism practice; IDCV—inclusive development for citizens and visitors; EI—economic indicator; ENI—environmental indicator; CI—cultural indicator; SI—social indicator.

While previous research has focused on the importance and challenges of the tourism industry in urban development, relatively little attention has been paid to the evaluation and review of the sustainable development of the tourism industry in industrial small cities. Scholars currently assess sustainable development in the tourism industry from several key aspects, including economic, social, environmental, and cultural indicators. These indicators are used to evaluate the long-term impact of tourism activities on local communities.

The selection of these indicators can vary significantly between industrial small cities and larger urban areas. In industrial cities, economic indicators often include assessments of industrial heritage revitalization and its impact on the local economy, while environmental indicators may evaluate the effects of industrial pollution on tourist sites. Social indicators focus on community engagement and the fair distribution of tourism benefits, while cultural indicators encompass the preservation of local industrial heritage and cultural identity.

Therefore, it is crucial to tailor the selection of indicators to the specific characteristics of industrial small cities to more accurately assess their sustainable development in the context of tourism. This study aims to fill this gap in the literature by providing a comprehensive review and analysis of the selection of sustainability indicators relevant to industrial small cities. Analyzing various factors, such as cultural, economic, environmental, and social indicators, allows for a deeper understanding of the complex interactions within sustainable tourism. Additionally, the study emphasizes the importance of involving local people in tourism planning processes, as this can help develop inclusive practices and increase social and cultural sustainability.

3. Methodology

3.1. Overall Questionnaire Design

This research used a mixed methods technique to address research problems. Mixed methods allow for a comprehensive exploration of the topic by integrating practical perspectives resulting from the combination of two different approaches—quantitative and qualitative [100,101,102]. The research began with an exploratory qualitative design, the results of which informed and guided the subsequent quantitative phase. This approach is beneficial as it produces results that are clear and directly applicable, contributing to the development of new constructs and variables tailored to the specific research topic. The questionnaire design and measurements were carefully crafted to encompass the multifaceted nature of sustainable urban tourism, integrating strategies and practices aimed at harmonizing different scopes of destination development (from environmental to economic). Predictors of sustainable urban tourism, such as the integration of tourism in urban planning (ITUP), sustainable urban tourism practices (SUTPs), and inclusive development for citizens and visitors (IDCV), were derived from the guidelines of the World Tourism Organization—UN Tourism [103], which is recognized as a prominent authority in the travel industry.

Additionally, assertions relating to economic indicators (EIs), social indicators (SIs), environmental indicators (ENIs), and cultural indicators (CIs) of sustainable urban tourism were extracted from extensive literature examining various aspects of this topic. This literature includes analyses of current trends, expert recommendations, and empirical research conducted in this field, enabling a comprehensive understanding and evaluation of practical applications tailored to the specificities of urban tourism and sustainable development. The vast number of constructs in the questionnaire itself indicates that all pertinent segments that may help shape opinions about the growth of sustainable urban tourism are covered. There were two sections to the questionnaire: (1) a demographic part, which collected basic information about the respondents, such as age, gender, occupation and education, to enable demographic data analysis; and (2) sustainable urban development statements, which contained a series of statements designed to assess respondents’ attitudes and perceptions of sustainable urban development SSCs.

3.2. Data and Sample Collection Procedure

A stratified random sample technique was used for this investigation to ensure adequate representativeness of the sample consisting of a total of 1218 respondents from the target population of local residents in two selected cities: Zrenjanin (Republic of Serbia) with 546 respondents and Satka (Russian Federation) with 672 respondents. Respondents were randomly selected from each urban stratum, allowing representation across diverse social groups. The research was conducted from February 2024 to May 2024. Initially, the survey was distributed to academic experts in Serbia’s travel industry. As part of this procedure, 25 questionnaires were distributed to professionals working in the travel industry as part of a pilot study. This stage attempted to improve the survey’s quality and identify areas that needed improvement, such as the quantity of questions, structures, and reliability analysis. The questionnaire was subsequently revised and translated to avoid mechanical errors and then distributed to all participants in the second phase. Data collection involved using survey questionnaires designed to quantitatively assess different aspects of sustainable urban tourism by measuring the perceptions and attitudes of the respondents. The questionnaire included items specifically created for each of the key constructs of the research, such as the integration of tourism into urban planning, sustainable tourism practices, and inclusive development for citizens and visitors. Respondents expressed their views using a Likert scale, where “1” indicated “strongly disagree”, and “7” indicated “strongly agree”.

Data preprocessing included several crucial steps to ensure the accuracy and integrity of the data. Missing data were addressed using multiple imputation methods. Specifically, the Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations (MICE) algorithm was utilized, which allowed for the estimation of missing values based on the observed data, thereby reducing potential biases [104]. Outliers were identified through a combination of statistical tests and visual inspections. Grubbs’ test was employed to detect single outliers, while Iglewicz and Hoaglin’s test was used for multiple outliers [104]. Identified outliers were carefully examined and, where appropriate, adjusted to fall within three standard deviations from the mean, ensuring they did not disproportionately affect the results. Data transformations were applied to normalize the distribution of the data. Skewed data were log-transformed (logarithmic transformation) to achieve normality. For variables with zero or negative values, a constant was added before transformation. Additionally, square root transformations were applied to stabilize variance for highly skewed datasets. After these transformations, the skewness and kurtosis values of the data were checked, and it was confirmed that they fell within the acceptable range of −1 to 1, indicating that the data were approximately normally distributed.

During the analytical process, it was observed that both Satka and Zrenjanin showed similar trends in the development of industrial sectors and urban tourism, despite geographical and cultural differences. Moreover, responses from the survey conducted among relevant experts and local populations also showed a high degree of similarity in perceptions and attitudes regarding developmental challenges in both cities. These similarities facilitated the integration of responses, resulting in a combined analysis. This integration provided an opportunity to better understand how industrial cities can direct their strategies toward tourism development and how industrial and tourism sectors can complement each other. Thus, the joint analysis was not only a methodological decision but also a logical response to the observed similarities in economic structures, development aspirations, and research outcomes of both cities. This approach allows for a more efficient synthesis of data and the formulation of stronger conclusions about the potentials and challenges faced by industrial cities in the context of globalization and changing economic trends. A broad examination of the economic transformation of SSCs in the examined nations, with an emphasis on the present prevailing trend of tourist growth, can justify the consolidation of surveys.

Table 1 shows the respondents’ sociodemographic characteristics, which have a slight male majority (53.3% vs. 46.7% female). The predominant group spans from 20 to 35 years of age, accounting for 41.7% of answers, indicating a younger demographic. In terms of education, the majority (63.5%) have a faculty degree, indicating a well-educated population. In terms of monthly income, the majority of respondents (69.1%) earn between 500 and 1000 euros, indicating that the middle-income group is the most common. Only 4.2% of respondents have advanced degrees (PhD, MSc), and a minority (27.3%) earn more than 1000 Euros each month.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics.

3.3. Data Analysis

Using SPSS software version 23.00, descriptive statistics were employed to illustrate the sample and determine its central tendency and variability. Initially, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was computed for the complete questionnaire, yielding a value of α = 0.872, indicating high internal consistency reliability [104]. The factor analysis with promax rotation identified 8 factors from the 29 elements. These factors were labeled as follows: ITUP (integrating tourism into urban planning) (S1–S4), SUTP (sustainable urban tourism practices) (S5–S8), IDCV (inclusive development for citizens and visitors) (S9–S13), EIs (economic indicators) (S14–S16), SIs (social indicators) (S17–S19), ENIs (environmental indicators) (S20–S22), CIs (cultural indicators) (S23–S25), and SUTs (sustainable urban tourism) (S26–S29).

Table 2 presents the measurement results for various statements related to sustainable urban tourism, including the mean (m), standard deviation (sd), Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (α), and factor loading (FL) for all 29 statements. These results quantitatively assess participants’ insights of the tourism influence on urban planning, sustainability, and social inclusion. The statements cover topics such as the integration of tourism into urban policy, promotion of sustainable tourism practices, involvement of local communities, and application of modern technology to improve tourist administration.

Table 2.

Measurement model results for statements.

The dataset reveals high Cronbach’s alpha values across most statements, indicating a robust measure of internal consistency. This consistency suggests that respondents exhibit uniform perceptions across diverse dimensions of urban tourism sustainability. Notably, the mean scores for these statements are predominantly above 4.5, signaling a favorable attitude toward the integration of sustainable practices within urban tourism planning. Regarding the variability in responses, it remains relatively low for the majority of items, highlighting a consensus among participants. Nevertheless, areas such as sustainable transport and waste management display higher standard deviations. This variability may reflect differing local contexts or varying degrees of implementation, suggesting that these aspects of urban tourism sustainability are perceived differently across different urban settings. The factor loadings substantiate that the statements serve as effective indicators of underlying factors. Statements particularly related to sustainable practices, policy integration, and community involvement demonstrate especially strong loadings, which are indicative of their perceived importance within the sustainability framework of urban tourism. The data robustly support the premise that successful urban tourism relies on comprehensive frameworks, innovative technological application, active participation from local communities, and strict adherence to global sustainability standards. These factors are not only instrumental in promoting environmental and cultural preservation but are also crucial for bolstering the economic and social infrastructure of urban destinations. Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics and reliability analysis for different constructs associated with the factors influencing sustainability of urban tourism.

Table 3.

Measurement model results for factors.

The integration of tourism in urban planning stands out with the highest mean score (5.20) and contributes 13.650% to the total variance, suggesting that it is perceived as crucial by respondents. The high α (0.875) and satisfactory CR (0.800) affirm the reliability and internal consistency of this construct. Sustainable tourism practices and inclusive development for citizens and visitors also show robust support with mean scores of 4.96 and 4.78, respectively, and similar levels of internal consistency (α > 0.874). These factors also account for significant portions of the variance, indicating their perceived importance in the sustainability of urban tourism. Economic indicators, although exhibiting the highest standard deviation (0.975), reflect the diversity of opinions about their impact yet still demonstrate substantial internal consistency and contribute notably to the cumulative variance, emphasizing their role in urban tourism sustainability. Social and environmental indicators show relatively lower mean scores but maintain high reliability measures and contribute significantly to understanding sustainability with social indicators explaining 5.148% and environmental indicators explaining 4.402% of the variance. Cultural indicators have a solid presence in the analysis with a mean score of 4.92, showcasing their relevance in fostering a sustainable tourism environment that respects and promotes local culture.

The sustainability of urban tourism as a construct has a relatively lower mean score (4.86) compared to others but stands out with the highest CR (0.943), indicating exceptional composite reliability. Its lower standard deviation (0.503) suggests that responders share a similar opinion on the significance of sustainable practices in urban tourism. Bootstrapping methods were used to assess the stability of parameter estimates. Specifically, 1000 bootstrap samples were generated, and estimates were recomputed for each sample. This procedure provided bias-corrected and accelerated confidence intervals (BCa), which helped to ensure that our results were not influenced by the overly specific sample used in the study, thereby increasing the generalizability of our findings.

We also conducted a sensitivity analysis to examine how changes in key assumptions affected the model results. This involved varying the input parameters over a reasonable range and observing the effects on the output. The analysis showed that the model results remained consistent across different scenarios, indicating high robustness. In addition, cross-validation techniques were used to further validate the predictive power of the model. The dataset was split into training and test sets using k-fold cross-validation (k = 10). This approach involved dividing the data into ten subsets, training the model on nine subsets, and testing on the remaining subset. This process was repeated ten times, with each subset serving as a test set for one week, allowing the model’s performance to be evaluated on different parts of the data. The results showed consistent performance of the model on all datasets, thus confirming its generalizability. Model fit indices such as root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI), and Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) were calculated to assess the overall model fit. The RMSEA value was 0.05, indicating a good fit, while the CFI and TLI values were above 0.95, suggesting that the model adequately captured the structure of the data. In addition to the primary data analysis techniques, we employed the PROCESS macro for SPSS, developed by Andrew F. Hayes, to conduct mediation and moderation analyses [104]. This allowed us to test complex models involving indirect and interaction effects. Specifically, we utilized Model 4 of the PROCESS macro to assess mediation effects and Model 1 for moderation effects. The analysis involved generating 1000 bootstrap samples to obtain bias-corrected confidence intervals, ensuring robust and reliable estimates of the indirect and interaction effects.

It is acknowledged that the two countries analyzed in this study have significant differences in terms of national size, industrial base, and spatial geographical distribution. These factors were considered during the analysis to ensure that the results reflect the unique characteristics of each country. While average statistical data were used for model validation, we recognize that this approach may obscure specific details and differences. Therefore, the impact of scale differences will be considered in future research to enhance the interpretability and applicability of the findings.

4. Findings

Table 4 awards the adjusted reliability and validity metrics for various constructs. All the constructs are related to the study on urban tourism sustainability in SSCs reflecting measurements of internal consistency, composite reliability, and convergent validity across all constructs.

Table 4.

Construct reliability and validity.

The Cronbach’s alpha and Omega reliability values range from 0.800 to 0.880, indicating excellent internal consistency across all constructs. These high values ensure that the constructs are reliably measuring the attributes they are intended to assess, thereby enhancing the credibility of the study’s outcomes. Composite reliability values now uniformly exceed the 0.8 threshold, with figures ranging up to 0.910. This shows a great degree of uniformity across the items comprising each construct, affirming that the constructs are coherent and capture the intended dimensions effectively. The AVE values, all above 0.5 and as precise as 0.560 in some constructs, signify strong convergent validity.

Table 5 displays discriminant validity assessments for multiple constructs related to urban tourism sustainability. Our analysis of discriminant validity, including the Fornell–Larcker criterion and HTMT ratios, demonstrated complete discriminant validity among the constructs examined in the urban tourism framework.

Table 5.

Checking of discriminant validity using Fornell–Larcker and HTMT criteria.

The square roots of the AVE for each construct were higher than the correlations of that construct with any other construct, which was consistent with the Fornell–Larcker criterion. Additionally, HTMT ratios were below the threshold of 0.85 for all pairs of constructs, further supporting discriminant validity. These low HTMT ratio values confirm that the constructs have clearly separated conceptual bases, which is crucial for the accuracy and reliability of our measurements. Diagonally shaded cells in the table assessing discriminant validity are used to visually highlight the key diagonal elements, representing the AVE for each construct. Coloring certain cells in the table serves to emphasize that each construct has a significant and unique amount of variance explained by its indicators, which is the foundation for confirming discriminant validity.

Table 6 presents the VIF for each statement related to research on urban tourism sustainability. The VIF is a measure used to detect the presence of multicollinearity among predictors in a regression model. A commonly accepted threshold for VIF is 3.3, above which the presence of multicollinearity becomes concerning as it can distort the reliability of the regression coefficients.

Table 6.

Collinearity statistics (variance inflation factor—VIF).

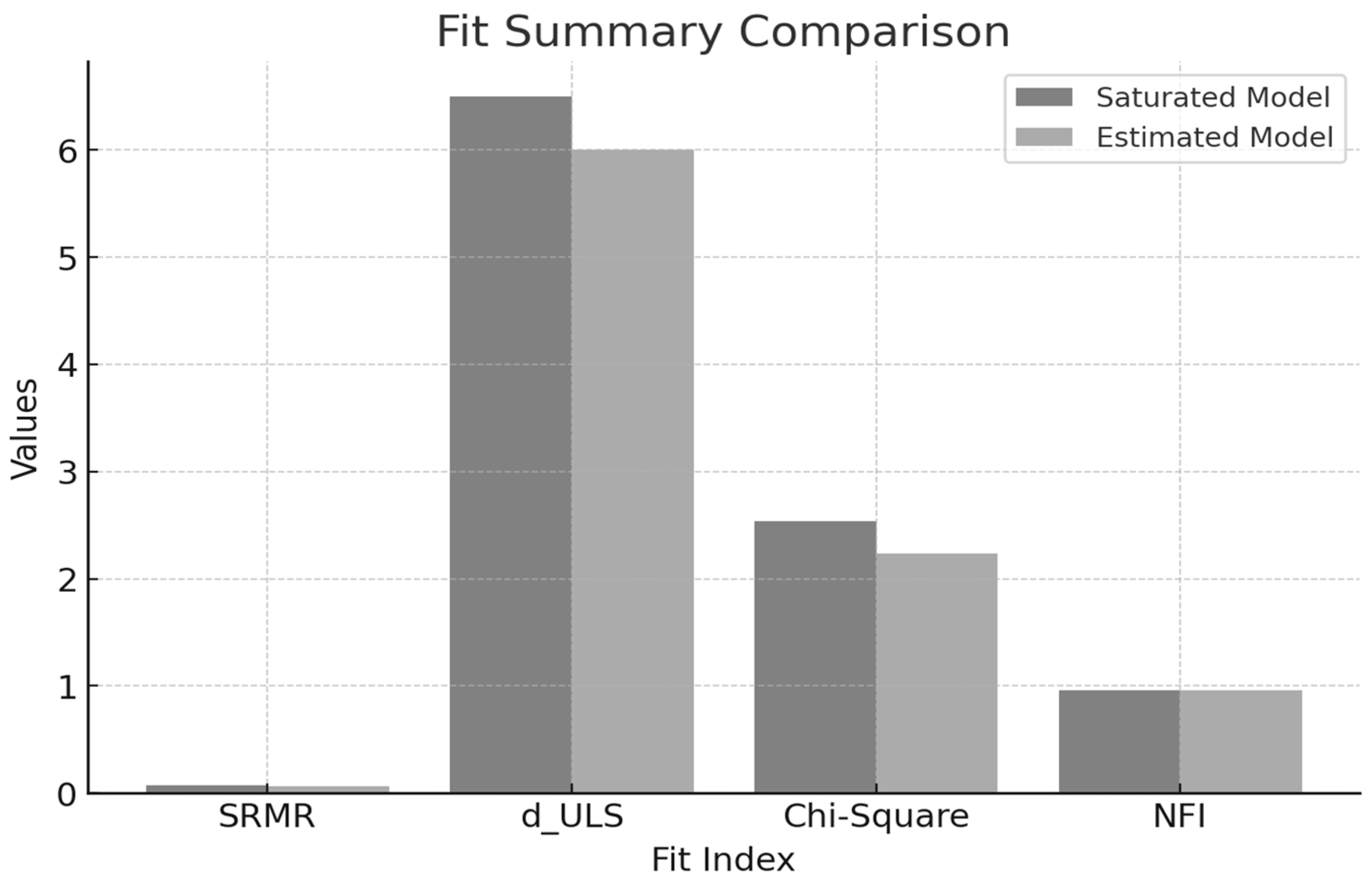

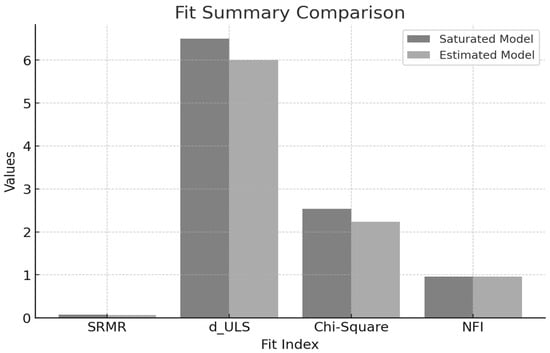

All listed VIF values fall below the threshold of 3.3, suggesting that there is no significant multicollinearity among the statements. This is crucial for the statistical validity of the regression models used in the study, as it ensures that the estimated coefficients are reliable and not overly influenced by redundant information. The VIF values range from 1.001 (S20) to 1.407 (S6), indicating very low to modest levels of collinearity. The majority of statements have VIF values close to 1, which is ideal and indicates very little collinearity. The highest VIF observed is for S6 (1.407), which, while being the highest in this dataset, still remains well below the threshold of concern. This reflects a well-specified model where predictors are not excessively overlapping in the information they provide about the dependent variable. Figure 2 presents a comparison of various fit indices for the saturated and estimated models in structural equation modeling, illustrating the models’ adherence to the observed data.

Figure 2.

Model fit indices.

The SRMR shows very close values, indicating minimal residuals in both models. The estimated model performs slightly better, suggesting more precise predictions. The d_ULS (Unweighted Least Squares deviation) values are also close, with the estimated model showing a slight improvement, which indicates better overall fit. Chi-square values are low for both models with the estimated model showing a marginally better fit. Lower Chi-square values suggest fewer discrepancies between expected and observed covariance matrices. The NFI remains constant at 0.962 in both cases, demonstrating that both models adequately explain the variance and covariance in the data relative to a null model. The p-values associated with these paths signify statistical significance, with most below the 0.05 threshold, affirming the robustness of the hypothesized relationships. The model demonstrates a perfect match, as demonstrated by the combined variance explained by all the constructs and the consistency of the mediator effects.

We also utilized the PROCESS macro for SPSS to empirically test mediation and moderation effects within our model. The analysis was conducted using Model 4 for mediation and Model 1 for moderation. The results included direct, indirect, and total effects along with associated confidence intervals obtained through bootstrapping (1000 samples). The detailed results are summarized in Table 7 and Table 8.

Table 7.

Mediation analysis results.

Table 8.

Moderation analysis results.

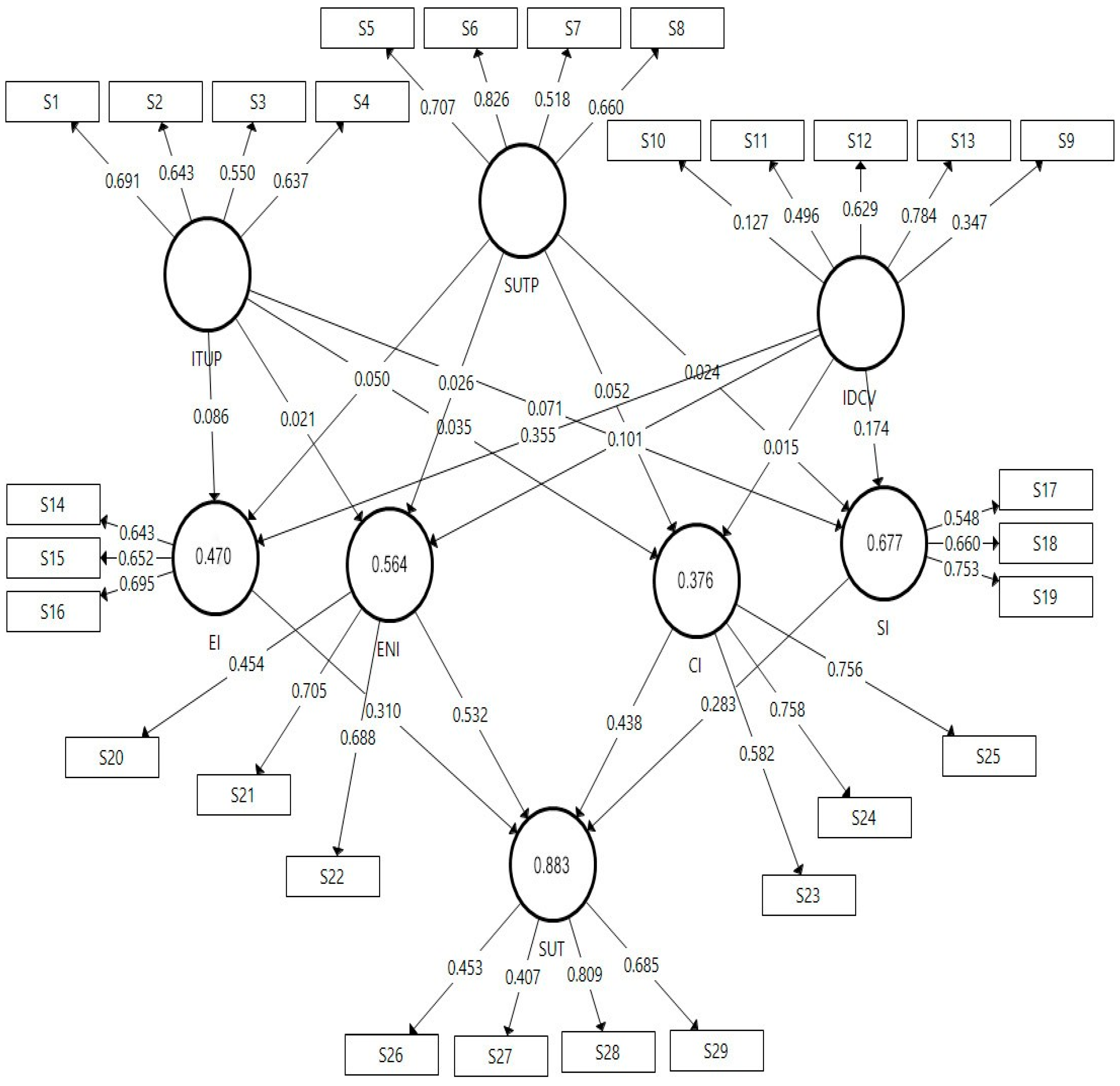

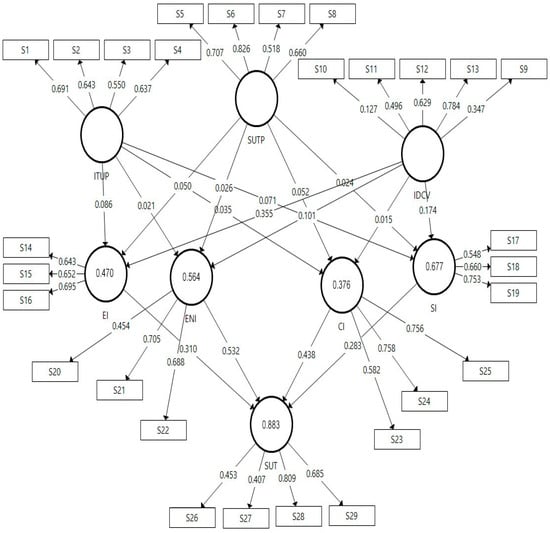

The further results are shown in Table 9 and Figure 3. The outcomes clearly demonstrate how different aspects of sustainable urban tourism in SSCs mediate the influence of underlying constructs on tourism sustainability. The analysis focused on the indirect effects of integration of tourism into urban planning (ITUP), sustainable urban tourism practices (SUTPs), and inclusive development for citizens and visitors (IDCV) through economic indicators (EIs), environmental indicators (ENIs), social indicators (SIs), and cultural indicators (CIs) on the sustainability of urban tourism (SUT). Structural equation modeling (SEM) showcases that economic indicators (EIs) elucidate 47.0% of the variance, while environmental indicators (ENIs) account for 56.4%, cultural indicators (CI) account for 37.6%, and social indicators (SI) account for 67.7% of the variance in urban tourism sustainability in predominantly industrial SSCs. These mediators, in conjunction with direct influences, comprehensively explain 88.3% of the variance in the sustainability of urban tourism (SUT), demonstrating a substantial collective impact.

Table 9.

Path coefficients and hypotheses testing results.

Figure 3.

Model testing results.

The structural equation model provides evidence for the significance of integrating tourism into urban planning (ITUP), implementing sustainable urban tourism practices (SUTPs), and fostering inclusive development for citizens and visitors (IDCV) in enhancing the sustainability of urban tourism (SUT). Notably, the explained variance in the sustainability of urban tourism by these predictors suggests that they are substantial but not exclusively determinant factors on their own. Figure 3 presents a comparison of various fit indices for the saturated and estimated models in structural equation modeling, illustrating the models’ adherence to the observed data. This comparison highlights how well each model fits with the empirical data, confirming the relevance and effectiveness of these factors in promoting sustainable urban tourism.

The integration of tourism into urban planning (ITUP) not only directly contributes to sustainability but also exerts significant indirect effects through various mediators. For instance, ITUP’s strongest impact is via economic indicators (β = 0.086, p = 0.014), affirming its critical role in sustainable economic growth. Conversely, its effect through environmental indicators, though weaker (β = 0.021, p = 0.010), remains meaningful, underscoring the nuanced balance between economic development and environmental preservation. Sustainable urban tourism practices (SUTPs) also demonstrate a beneficial indirect influence across all sustainability dimensions with a pronounced effect on cultural indicators (β = 0.052, p = 0.021). This finding highlights the pivotal role of cultural sustainability in strengthening the overall fabric of urban tourism. Inclusive development for citizens and visitors (IDCV) reveals a compelling pattern of influence, particularly through economic indicators (β = 0.355, p < 0.001), suggesting that economic inclusivity is paramount for sustainable urban development. Moreover, even though the impact through cultural indicators is relatively modest (β = 0.015, p = 0.004), it is crucial for fostering a culturally vibrant urban tourism environment.

The direct effects of these practices on sustainability are equally significant. Economic indicators not only mediate other impacts but also directly drive sustainability (β = 0.310, p = 0.005), proving that economic health is foundational to sustainable urban tourism. Social indicators, representing social inclusion and cohesion, directly enhance sustainability (β = 0.283, p = 0.019), which reflects the social dimension’s integral role in creating harmonious urban environments. Environmental sustainability, mediated by eco-friendly practices, shows the strongest direct effect (β = 0.532, p < 0.001), emphasizing the urgent need for environmental considerations in urban planning. Lastly, cultural indicators significantly contribute to overall sustainability (β = 0.438, p < 0.001), highlighting the importance of cultural heritage and diversity in enriching the urban tourist experience and promoting sustainable growth.

The results section has been expanded to include a detailed analysis of the important findings derived from the use of structural equations to analyze the survey questionnaire. Specifically, we have highlighted the key factors contributing to the sustainability of urban tourism in SSCs and discussed the implications of these findings for Zrenjanin and Satka. This includes examining how economic, social, environmental, and cultural indicators mediate the effects of integrating tourism into urban planning and sustainable tourism practices.

5. Discussion

This study has focused on the incorporation of tourism within city planning in SSCs in Serbia and Russia. The key findings indicate significant impacts of integrating tourism into urban planning and implementing sustainable tourism practices on urban tourism sustainability. These results are consistent with previous research, yet they also highlight unique contributions and innovations of this study. The discussion will extract the main research results, comparing them with previous studies to address common issues in contributions and limitations, and highlight the unique aspects that distinguish this study from others. The main objective is to identify and evaluate how these practices can support urban tourism’s sustainability on an ecological, economic, social, and cultural level. It is the study’s goal to close a gap in the existing literature by exploring the direct and indirect impact of sustainable practices on various aspects of urban tourism sustainability. Using stratified random sampling and structural equation modeling (SEM) allowed for a precise analysis of data collected from 1218 participants. The validity of the model was confirmed by high values for the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, indicating the reliability of the scale, and confirming the suitability of the data for factor analysis. Research variables include the integration of tourism into urban planning (ITUP), sustainable urban tourism practices (SUTPs), and inclusive development for citizens and visitors (IDCV). These variables served as predictors to assess their impact on urban tourism sustainability, with cultural, economic, environmental, and social indicators (CIs, EIs, ENIs, and SIs) used as mediators.

The research results showed that the ITUP has a significant indirect impact on all dimensions of sustainability. This confirms hypotheses H1a–d, which suggest that ITUP indirectly affects sustainability through cultural, economic, environmental, and social indicators. Similarly, sustainable urban tourism practices (SUTPs) showed a positive indirect impact (hypotheses H2a–d), indicating that the implementation of sustainable practices can significantly improve all aspects of urban tourism sustainability. The study by Aall and Koens [58] further strengthens these findings, highlighting how the active integration of tourism into urban development strategies can contribute not exclusively to economic and social sustainability but also to the overall progress of cities. Their analysis shows that tourism integration can significantly contribute to the local economy and social cohesion, which directly resonates with our findings on economic and social sustainability indicators. This parallelism underscores the universal value of tourism integration into urban plans as a strategy for achieving broader sustainable goals, confirming the importance of our results within the larger framework of tendencies in urban development worldwide. This emphasizes the need for further research and policy development to maximize the potential of tourism in urban development on a global level.

Our research on inclusive development for citizens and visitors (IDCV) revealed its indirect effects on sustainability, while direct impacts were less pronounced. These findings confirm hypotheses H3a–d and highlight the initial suspicious. The approach not only enhances social sustainability but also encourages communities to take greater ecological responsibility. The study by Dwyer and Edwards [81] provided additional support for these findings, demonstrating that involving local communities in tourism practices can significantly improve both social and environmental sustainability. Their results clearly show that the active participation of local communities in tourism not only increases their benefits and satisfaction but also contributes to the preservation and protection of the local environment. This underscores the importance of IDCV in creating sustainable tourism initiatives that are beneficial and acceptable to the local population while ensuring that tourism positively contributes to the broader community and environment [105]. These insights further support the argument that it is crucial to develop policies and practices that focus on the inclusion and participation of local communities in tourism planning and management, which is not only an ethical approach but also a strategy that leads to more sustainable and responsible tourism development in urban areas [106].

Direct effects are evident in the model through relationships between independent variables such as the integration of tourism into urban planning (ITUP), sustainable urban tourism practices (SUTPs), and inclusive development for citizens and visitors (IDCV) with dependent variables, including economic, social, environmental, and cultural sustainability indicators. Our research has shown that the direct effects of economic indicators (EIs) on urban tourism sustainability are evident and confirm that economic sustainability is crucial for this purpose. The outcomes are related with Maxim’s [42] research, who examined how the implementation of sustainable practices affects the urban tourism progress, with a specific focus on environmental and cultural indicators. His results have shown that sustainable practices significantly improve the perception of tourist destinations and contribute to the long-term preservation of cultural and natural resources.

Indirect effects were explored through a mediation analysis, demonstrating how independent variables influence dependent variables through mediators. For example, the integration of tourism into urban planning (ITUP) shows indirect effects on sustainability through cultural, economic, environmental, and social indicators. This suggests that although primary strategies may not have a direct impact, their indirect effects through mediators such as cultural and environmental indicators have a significant position in determining sustainable outcomes. The mediation of cultural indicators in the relationship between the ITUP and urban tourism sustainability illustrates how cultural preservation and valorization can enhance overall sustainability. This mechanism indicates that properly integrated tourism not only respects and promotes local cultural values but also actively contributes to their preservation. Similarly, environmental indicators mediate the relationship between sustainable urban tourism practices (SUTPs) and sustainability, suggesting that initiatives such as natural resource protection and waste reduction have a vital impact on enhancing the ecological dimension of sustainability. Richards’ results [107] further supported these findings, highlighting how the integration of tourism into urban infrastructure and planning can transform urban centers, providing new opportunities for creative urban hubs’ development. Their findings align with the importance of ITUP for sustainability, demonstrating that strategic planning approaches can have far-reaching positive effects on the urban environment. This synergy between cultural valorization and ecological sustainability supports the concept that tourism integration can be crucial not only for preserving the identity and resources of the city [108].

In terms of the obtained results, we were able to identify key factors contributing to the sustainability of urban tourism industrial SSCs. Additionally, we have established connections with similar research, corroborating our findings and supporting the wider knowledge on successful urban tourism practices globally.

Q1: How does the implementation of sustainable urban tourism practices affect diverse sustainable features (social, economic, environmental, and cultural) in SSCs?

The SUTP has shown significant indirect effects on all aspects of sustainability in urban environments [109]. Our research indicates that such practices, including waste reduction, the use of renewable energy sources, and the promotion of local culture, directly contribute to environmental and cultural sustainability. Additionally, these practices increase the economic value of tourist destinations and enhance social cohesion, thereby improving the overall quality of life for local communities. Hunter [110] emphasized the importance of sustainable tourism practices that not only contribute to resource conservation and reducing the ecological footprint but also promote social justice in tourist destinations. Concurrently, Bramwell [111] analyzed how sustainable tourism practices impact economic development and the quality of life of local communities. His research confirms that sustainable practices positively impact economic sustainability, emphasizing how strategic management and the integration of sustainability into tourism policies can result in significant benefits for local communities and broader society. The implementation of sustainable tourism practices has a wide range of impacts on sustainability in urban environments, as shown by a 2018 study analyzing digital traces of tourists in urban spaces, exploring how tourists use and navigate urban spaces [112]. This study highlights the potential for reducing the ecological footprint and enhancing cultural valorization through thoughtful sustainable practices.

Q2: What are the effects of integrating tourism into urban planning processes on the sustainable outcomes of urban tourism?

The ITUP has a crucial indirect impact on the sustainable outcomes of urban tourism [113]. Our study has revealed that when tourist activities are aligned with urban development plans, better economic, social, environmental, and cultural outcomes are achieved. Istoc [114] demonstrated how properly integrated tourism can play a key role in supporting urban regeneration and sustainable development, demonstrating the positive effects of tourism integration on urban infrastructure. This research highlights how the strategic integration of tourism activities into urban planning can contribute to the revitalization of urban areas and the enhancement of quality of life. Similarly, Edwards and Griffin [115] analyzed how tourism integration can promote sustainable outcomes through improving the local economy and protecting the urban environment. Their research indicates that tourism integration not only stimulates economic development but also provides tools for a more efficient protection and preservation of cities’ natural and cultural resources, confirming the significance of this practice in promoting sustainable urban development. The integration of tourism into urban planning can significantly contribute to sustainable outcomes [116]. This research underscores how urban policy can impact tourism in cities, suggesting longitudinal studies for a better understanding of this phenomenon.

Q3: How can inclusive development and engagement of the local community enhance the positive effects of sustainable urban tourism?

Inclusive development for citizens and visitors (IDCV) has shown that the role of local residents in the processes of planning and managing tourism can significantly enhance the positive effects of sustainable urban tourism [117]. Community engagement not only enhances social sustainability through increased participation and satisfaction of the local population but also promotes environmental responsibility. Moreover, when citizens actively participate in tourism initiatives, it leads to greater transparency, fairness, and sustainable development that respects local needs and traditions. Cole [118] deeply explored the role of involving local communities in tourism projects, highlighting how such practice can significantly improve social cohesion and economic sustainability. In parallel, Tosun [19] stated that community engagement not only enhances social sustainability but also enables a more efficient protection of natural and cultural resources through sustainable tourism. The same author [19] emphasized that community participation is crucial for the realization of sustainable tourism initiatives, as it contributes to the preservation and valorization of the local environment and cultural heritage, further underscoring the need for integrating this practice into tourism development policies. Engaging the local community in tourism can amplify sustainable effects, as confirmed by a 2018 study on managing urban tourism growth through perceptions. This study analyzes residents’ attitudes toward tourism in several European cities and proposes strategies for managing visitor growth sustainably.

Q4: Which specific strategies for overcoming industrial constraints and industrial heritage can enable the successful integration of sustainable tourism in predominantly industrial small-sized cities (SSCs)?

To effectively integrate sustainable tourism into predominantly industrial small-sized cities, it is essential to leverage industrial heritage by transforming historical sites into educational attractions, highlighting the city’s unique history. Engaging local communities ensures the equitable distribution of benefits and fosters broad support for tourism initiatives. Investing in eco-friendly infrastructure like sustainable transportation and waste management minimizes environmental impacts. Aligning tourism development with urban planning enhances public spaces and amenities, while promoting local culture and businesses enriches tourist experiences and boosts the local economy. These strategies collectively foster economic growth and enhance both social and environmental sustainability as cities transition toward tourism.

In the study of the integration of sustainable tourism in post-communist cities, it is clear that there are parallels with broader global research on sustainable tourism in SSCs. Specifically, Light et al. [119] and Barrado-Timon et al. [120] stressed the importance of the shifting dynamics in these urban environments, highlighting the importance of cultural heritage and the economy of culture in sustainable development. These findings resonate with insights from Badoc-Gonzales et al. [121], who proposed sustainable frameworks for tourism in regions recovering from natural disasters in the Philippines, emphasizing the universal applicability of sustainable tourism principles across various geographical and socioeconomic contexts. Furthermore, the work by Swati and Ruby [122] on sustainable tourism in small cities complemented these studies by providing a bibliometric analysis that underscores the significance of digital strategies in economic recovery post-COVID-19. This aligns with the focus on economic and cultural sustainability discussed by Moral-Moral and Fernandez-Alles [123], who explored local perceptions of urban and industrial tourism as a model for sustainable tourism development. Similarly, Givental et al. [124] investigated the tourism potential of post-industrial resources in Russia, highlighting unrealized opportunities that could be utilized for sustainable urban tourism development. These cohesive findings underscore a common understanding among scholars that sustainable tourism can serve as a key driver for cultural, economic, and ecological revitalization in small cities focused exclusively on industrial development. This synergy in the global discourse not only strengthens the validity of our research but also enriches strategic approaches to sustainable urban tourism development in SSCs.

While the model results indicate a high degree of correlation and similar characteristics between the two countries, it is important to acknowledge the limitations in interpretability due to significant differences in national size, industrial base, and spatial geographical distribution. The use of average statistical data may obscure specific details and differences. Future research should consider the impact of scale differences to provide more nuanced insights into the integration of sustainable tourism in diverse industrial contexts.

In addition to the methodological approaches discussed, it is important to acknowledge that many small industrial towns often lack the resources to effectively attract potential tourists. Addressing the demand side of tourism requires practical strategies that go beyond merely improving municipal services. Small industrial towns can benefit from developing partnerships with local businesses and stakeholders to create unique and attractive tourist packages. Leveraging digital marketing and social media is also crucial for reaching a wider audience. Offering incentives and support for small local businesses to participate in tourism activities, organizing community events and festivals to showcase local culture, and seeking funding and grants aimed at boosting tourism infrastructure and services are all essential strategies. These approaches can help small industrial towns overcome resource limitations and better secure potential tourists, fostering a more sustainable and inclusive approach to urban tourism.

6. Conclusions

The research outcomes clearly demonstrate that the integration of tourism development into the urban planning of predominantly industrial SSCs, sustainable tourism practices, and inclusive development for citizens and visitors have vital roles in the sustainability of urban tourism. This analysis revealed that these practices not only directly influence all aspects of sustainability but also influence them indirectly through mediating effects. Economic and cultural indicators particularly stand out as key mediators transferring positive effects to the sustainability of urban tourism in SSCs, while environmental and social indicators also contribute, albeit to a slightly lesser extent. We should underline the fact that some of the effects, although statistically significant, exhibited relatively weak intensity.

These findings underscore the importance of a comprehensive approach in urban tourism planning that encompasses various dimensions of sustainability. They confirm the need for policies and practices that promote integration, innovation, and inclusivity in all aspects of urban development to guarantee the sustainable development of urban tourism in industrial SSCs. Such results provide clear guidelines for further strategic planning and development in the urban tourism sector.

This study contributes to the theoretical understanding of sustainable tourism principles in industrial small-sized cities, highlighting the importance of incorporating tourism into urban planning and implementing sustainable strategies. Practical implications include developing partnerships with local businesses, leveraging digital marketing, organizing community events, and improving municipal services. These strategies can help small industrial towns overcome resource limitations and better secure potential tourists.

Studies on sustainable principles and urban growth in SSCs face several challenges that affect the generalization and interpretation of results. Financial constraints are critical, as the funds required for sustainable infrastructure and innovative practices often exceed available resources, hindering the broader implementation and testing of sustainable tourism initiatives. Limited access to reliable data complicates the analysis of sustainable practices’ impacts. The accuracy and comprehensiveness of collected data are crucial for understanding urban tourism dynamics. The research may not capture all key sustainability variables, such as political, socioeconomic, and cultural factors. Sample representativeness issues can further hinder the assessment of sustainable practices’ effectiveness in various urban contexts. Urban population heterogeneity and tourist flows can lead to variations in the perception and acceptance of sustainable tourism initiatives. Subjectivity in interpreting sustainable tourism poses challenges, as different stakeholders may have varying opinions on sustainable practices and their benefits, affecting the interpretation and practical application of results. Although some effects are statistically significant, their practical significance may be weaker than expected, indicating a need for further research to strengthen these effects and improve practical application. An integrated approach is needed to forecast and apply sustainable principles in industrial SSCs. This includes engaging all relevant stakeholders, enhancing financial and technological resources, developing more effective policies, and intensifying educational campaigns on the importance of sustainable development. These measures can help overcome existing barriers and create a stronger, more inclusive system of urban tourism in SSCs.

This research lays the foundation for further studies on incorporating sustainable practices into urban tourism frameworks in SSCs focused on industrial growth. Comparative studies can illuminate how these practices are implemented and adapted in different countries, identifying effective strategies for various socioeconomic contexts. Detailed analyses of specific sustainable interventions, such as green technologies or community engagement programs, will provide insights into their application, challenges, and effectiveness. Examining legal frameworks can identify key supports or barriers to sustainable urban tourism and assess the impact of policies, regulations, subsidies, and tax incentives on project success. Long-term studies can monitor how sustainable tourism affects the social, economic, and environmental aspects of communities, revealing lasting changes brought about by tourism. Research into modern technological innovations can enhance the management, monitoring, and evaluation of sustainable tourism activities. These research avenues offer significant opportunities to expand knowledge and develop environmentally friendly methods that protect the environment and improve local communities, making urban tourism more sustainable and inclusive.

Although this study offers significant insights into the integration of sustainable tourism in two countries with differing industrial profiles, it is essential to recognize the considerable disparities in national size, industrial structure, and geographical distribution. Future studies should focus on these differences more explicitly to enhance the interpretability and relevance of the findings across diverse contexts.

Although this study offers significant insights into the integration of sustainable tourism in predominantly industrial small-sized cities (SSCs), it is crucial to recognize the substantial disparities in national size, industrial structure, and geographical distribution between the analyzed countries. Future research should explicitly address these differences to enhance the interpretability and applicability of the findings across diverse contexts.

To support small industrial towns lacking resources for attracting tourists, practical recommendations include developing partnerships, leveraging digital marketing, and organizing community events. These strategies, coupled with improving municipal services, can foster a more sustainable and inclusive approach to urban tourism.

Overall, the integration of tourism into urban planning, sustainable tourism practices, and inclusive development is key to promoting the sustainability of urban tourism in SSCs. These findings provide clear guidelines for further strategic planning and development in the urban tourism sector.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.D.P. and T.G.; methodology, M.D.P. and T.G.; software, M.M.R.; validation, I.D.T. and E.D.B.; formal analysis, T.G. and M.M.R.; investigation, M.D.P. and T.G.; resources, M.M.R.; data curation, I.D.T. and E.D.B.; writing—original draft preparation, T.G.; writing—review and editing, M.D.P.; visualization, I.D.T. and E.D.B.; supervision, M.M.R. and E.D.B.; project administration, I.D.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The research was supported by the Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation of the Republic of Serbia (Contract no. 451-03-66/2024-03/200172), by the Russian Scientific Foundation (Grant no. 22-18-00679, «Creative reindustrialization of the second-tier cities in context of digital transformation»), and by the RUDN University (Grant no. 060509-0-000).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Escalona-Orcao, A.; Barrado Timón, D.A.; Escolano-Utrilla, S.; Sánchez-Valverde, B.; Navarro-Pérez, M.; Pinillos-García, M.; Sáez-Pérez, L.A. Cultural and Creative Ecosystems in Medium-Sized Cities: Evolution in TimesofEconomicCrisisandPandemic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressan, A.; Pedrini, M. Exploring sustainable-oriented innovation within micro and small tourism firms. Tour. Plan Dev. 2020, 17, 497–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionica, A.; Samuil, I.; Leba, M.; Toderas, M. The path of petrila mining area towards future industrial heritage tourism seen through the lenses of past and present. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, L.; Bolici, R. How to Become a Smart City: Learning from Amsterdam. In Smart and Sustainable Planning for Cities and Regions. Green Energy Technol. 2016, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]