Transformation of the Cultural Landscape in the Central Part of the Historical Region of Warmia in Poland

Abstract

1. Introduction

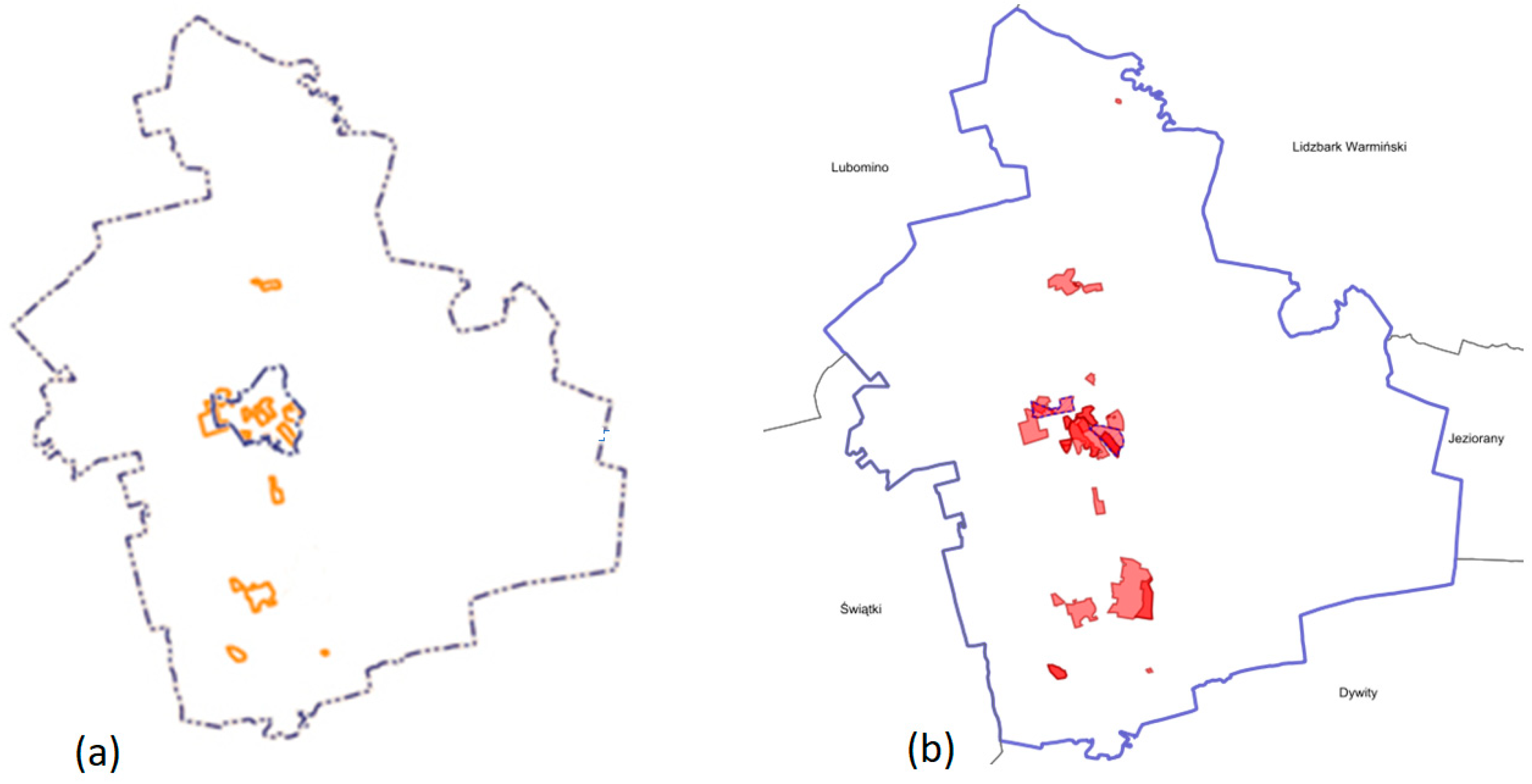

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of the Study Area

2.2. Research Methodology

| Criteria | Point Grading Scale | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Elements of the Cultural Heritage | Points | ||

| I | Objects generally classified as cultural monuments * | Historic palaces, historic parks | 5 |

| Historic urban layout | 5 | ||

| Churches, chapels, Stations of the Cross, towers | 5 | ||

| Cemeteries, roadside shrines, and crosses | 3 | ||

| Historic farmhouses | 3 | ||

| Archeological sites | 3 ** | ||

| Historic residential and commercial buildings | 1 | ||

| Buildings with valuable architecture | 1 | ||

| II | Objects of unique significance for the region’s cultural heritage | Objects that are unique on the national scale | 5 |

| Objects that are unique on the regional scale | 3 | ||

| Objects with typical and repetitive features | 1 | ||

| III | Significance for the cultural landscape (historic and architectural value, level of preservation) | High | 5 |

| Moderate | 3 | ||

| Low | 1 | ||

| IV | General landscape composition | Harmonious | 5 |

| Partly disrupted | −3 | ||

| Disrupted | −5 | ||

3. Results

3.1. Warmian Cultural Landscape

3.2. Planning Regulations in the Urban–Rural Municipality of Dobre Miasto

3.3. Assessment of Cultural Heritage Value

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jones, M. The Concept of Cultural Landscape: Discourse and Narratives. In Landscape Interfaces; Palang, H., Fry, G., Eds.; Landscape Series; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2003; Volume 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnoletti, M. Rural landscape, nature conservation and culture: Some notes on research trends and management approaches from a (southern) European perspective. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 126, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berninger, O. Krajobraz i jego składnik. In Kształtowanie Krajobrazu a Ochrona Przyrody; Buchwald, K., Ed.; PWRiL: Warsaw, Poland, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Richling, A.; Solon, J. Ekologia Krajobrazu; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanowski, J.; Łuczyńska-Bruzda, M.; Novak, Z. Architektura Krajobrazu; PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Polish Government. Nature Conservation Act of 16 April 2004 (Journal of Laws, 92/2004, Item 880); Internetowy System Aktów Prawnych (ISAP): Warsaw, Poland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. European Landscape Convention; adopted in Florence on 20 October 2000; Treaty Office of the Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanowski, J. Czytanie Krajobrazu. Kraj. Dziedzictwa Nar. 2002, 1, 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Rössler, M. World Heritage cultural landscapes: A UNESCO flagship programme 1992–2006. Landsc. Res. 2006, 31, 333–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Światowe Dziedzictwo. 19 September 2016. Available online: http://www.unesco.pl/kultura/dziedzictwo-kulturowe/swiatowe-dziedzictwo/ (accessed on 1 July 2024). (In Polish).

- Degórski, M. Krajobraz jako odbicie przyrodniczych i antropogenicznych procesów zachodzących w megasystemie środowiska geograficznego. Probl. Ekol. Kraj. 2009, 13, 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Banaszak, J.; Wiśniewski, H. Podstawy Ekologii; Wydawnictwo WSP: Bydgoszcz, Poland, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Eshrati, P.; Hanachi, P. A new definition of the concept of cultural landscape based on its formation process. Naqshejahan-Basic Stud. New Technol. Archit. Plan. 2015, 5, 42–51. Available online: http://bsnt.modares.ac.ir/article-2-10142-en.html (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Andreychouk, V. Cultural Landscape Functions. In Landscape Analysis and Planning; Luc, M., Somorowska, U., Szmańda, J., Eds.; Springer Geography; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyurkovich, M.; Pieczara, M. Using composition to assess and enhance visual values in landscapes. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terkenli, T. Towards a Theory of the Landscape: The Aegean Landscape as a Cultural Image. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2001, 57, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polish Government. Act of 23 July 2003 on the Protection and Conservation of Historic Monuments; (Journal of Laws, 2022, Item 840); Internetowy System Aktów Prawnych (ISAP): Warsaw, Poland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ostaszewska, K. Geografia Krajobrazu. Wybrane Zagadnienia Metodologiczne; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Dubel, K. Problemy kształtowania i ochrony krajobrazu. Fragm. Agron. 2002, 73, 41–57. [Google Scholar]

- Małachowicz, E. Ochrona Środowiska Kulturowego; PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 1988; Volume 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Sztafrowski, M. Architektura w Krajobrazie; Wydawnictwo Politechniki Gdańskiej: Gdańsk, Poland, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Dobrowolska, M. Dynamika krajobrazu kulturalnego. Przegląd Geogr. 1948, 1, 151–203. [Google Scholar]

- Myga-Piątek, U. Przemiany krajobrazów kulturowych w świetle idei zrównoważonego rozwoju. Probl. Ekorozwoju 2010, 5, 95–108. [Google Scholar]

- Mazurski, K.R. Pojęcie krajobrazu i jego ocena. In Mijające Krajobrazy Polski. Dolny Śląsk. Krajobraz Dolnośląski Kalejdoskopem Jest…; Mazurski, K.R., Ed.; Proksenia: Krakow, Poland, 2012; pp. 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Plit, F. Krajobraz w przestrzeni czy przestrzeń w krajobrazie. Pr. Kom. Kraj. Kult. 2014, 24, 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Kozłowski, L. Rozłogi wsi jako treść krajobrazu. In Planowanie Rozwoju Przestrzeni Wiejskiej; Kurowska, K., Gwiaździńska-Goraj, M., Eds.; Studia Obszarów Wiejskich, IGiPZ PAN: Warsaw, Poland, 2012; Volume 29, pp. 9–30. [Google Scholar]

- Ozimek, A. Landscape dominant element–an attempt to parameterize the concept. Tech. Trans. 2019, 116, 35–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Fang, Y.; Yan, Q.; Chen, C. Modern zoning plans versus traditional landscape structures: Ecosystem service dynamics and interactions in rapidly urbanizing cultural landscapes. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 331, 117315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rookwood, P. Landscape planning for biodiversity. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1995, 31, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polish Government. Act of 27 March 2003 on Spatial Planning and Development (Journal of Laws, 80/2003, Item 717); Internetowy System Aktów Prawnych (ISAP): Warsaw, Poland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Polish Government. Act of 15 February 1962 on the Protection of Cultural Heritage and Museums (Journal of Laws, 10/1962, Item 48, as Amended), Article 5, Point 12; Internetowy System Aktów Prawnych (ISAP): Warsaw, Poland, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Polish Government. Nature Conservation Act of 16 October 1991 (Journal of Laws, 114/1991, Item 492, as Amended); Internetowy System Aktów Prawnych (ISAP): Warsaw, Poland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Polish Government. Strategia Rozwoju Kapitału Społecznego 2030. Warsaw, Poland. 2020. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/ia/strategia-rozwoju-kapitalu-spolecznego-2030-srks (accessed on 10 March 2024).

- Silverman, H.; Ruggles, D.F. Cultural heritage and human rights. In Cultural Heritage and Human Rights; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 3–29. [Google Scholar]

- Borowiecki, K.J.; Forbes, N.; Fresa, A. Cultural Heritage in a Changing World; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; p. 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sesana, E.; Gagnon, A.S.; Ciantelli, C.; Cassar, J.; Hughes, J.J. Climate change impacts on cultural heritage: A literature review. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang. 2021, 12, e710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Högberg, A.; Holtorf, C. (Eds.) Cultural Heritage and the Future; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, O.E.; Duguma, L.A.; Minang, P.A. Operationalizing the integrated landscape approach in practice. Ecol. Soc. 2015, 20, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, J.; Van Vianen, J.; Deakin, E.L.; Barlow, J.; Sunderland, T. Integrated landscape approaches to managing social and environmental issues in the tropics: Learning from the past to guide the future. Glob. Change Biol. 2016, 22, 2540–2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Defries, R.; Rosenzweig, C. Toward a whole-landscape approach for sustainable land use in the tropics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 19627–19632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Verburg, P.H.; Liu, L.; Eitelberg, D.A. Spatial analysis of cultural heritage landscapes in rural China: Land use change and its risks for conservation. Environ. Manag. 2016, 57, 1304–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Cheshmehzangi, A.; Chan, F.K.S.; Ives, C.D. Mapping the research landscape of nature-based solutions in urbanism. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, M.F.; Herrero-Jáuregui, C. Cultural landscape preservation and social–ecological sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wantuch-Matla, D.; Dorocki, S.; Kroczak, R. Spatial, Functional, and Landscape Changes in a Medium-Sized Post-Industrial City Based on Aerial Photo Analysis: The Case of Gorlice (Poland). Sustainability 2023, 15, 11821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosgrove, D. Cultural Landscapes. In A European Geography; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 65–81. [Google Scholar]

- Fagerholm, N.; Martín-López, B.; Torralba, M.; Oteros-Rozas, E.; Lechner, A.M.; Bieling, C.; Olafsson, A.S.; Albert, C.; Raymond, C.M.; Garcia-Martin, M.; et al. Perceived contributions of multifunctional landscapes to human well-being: Evidence from 13 European sites. People Nat. 2020, 2, 217–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieling, C.; Plieninger, T.; Pirker, H.; Vogl, C.R. Linkages between landscapes and human well-being: An empirical exploration with short interviews. Ecol. Econ. 2014, 105, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, F.; Stephens, J.; Tiwari, R. Grounded theory as an approach for exploring the effect of cultural memory on psychosocial well-being in historic urban landscapes. Soc. Sci. 2020, 9, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K.; Lennon, J. Cultural landscapes: A bridge between culture and nature? Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2011, 17, 537–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farina, A. The cultural landscape as a model for the integration of ecology and economics. BioScience 2000, 50, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anelli, D.; Tajani, F. Valorization of cultural heritage and land take reduction: An urban compensation model for the replacement of unsuitable buildings in an Italian UNESCO site. J. Cult. Herit. 2022, 57, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Torre, S.; Boniotti, C. Innovative funding and management models for the conservation and valorization of public built cultural heritage. In Eresia ed Ortodossia nel Restauro. Progetti e Realizzazioni; Arcadia Ricerche: Marghera, Italy, 2016; pp. 105–114. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen-Jansen, L.; Spaans, M.; van der Veen, M. New Instruments in Spatial Planning. An International Perspective on Non-Financial Compensation; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Di Liddo, F.; Morano, P.; Tajani, F. Cultural and religious heritage enhancement initiatives: A logic-operative method for the verification of the financial feasibility. J. Cult. Herit. 2023, 62, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Meulen, M. Interior convertions: Redesigning the Village Church for Adaptive Reuse. IN_BO. Ric. Progett. Per Il Territ. Città L’architettura 2017, 8, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, T.C. Placemaking in a Postsecular Age: Sorting” Sacred” from” Profane” in the Adaptive Reuse of Relegated U.S. Catholic Churches. U.S. Cathol. Hist. 2023, 41, 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velthuis, K.; Spennemann, D.H. The future of defunct religious buildings: Dutch approaches to their adaptive re-use. Cult. Trends 2007, 16, 43–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaszczak, A.; Denekas, J. Znaczenie cech krajobrazu w kreowaniu przestrzeni kulturowej w układach regionalnych (The importance of landscape features in shaping cultural space in regional systems). Pr. Kom. Kraj. Kult. 2014, 25, 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Zagroba, M. Historical spatial structures in small towns and their role in the cultural landscape: A case study of towns in the polish region of Warmia. Bull. Geogr. Socio-Econ. Ser. 2023, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environmental Protection Program for Dobre Miasto Municipality for 2022–2025, with a Perspective Development Plan until 2030. 2021. Dobre Miasto. Available online: https://dobremiasto.com.pl/images/program-ochrony-srodowiska.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2024).

- Królikowska, H. (Ed.) Dobre Miasto na Starych Widokówkach; Pracownia Wydawnicza ElSet: Olsztyn, Poland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Local Revitalization Plan for Dobre Miasto for 2005–2008, with a Projection until 2013; Update for 2007–2015. Available online: https://bip.dobremiasto.com.pl/10044/3602/Program_Ochrony_Srodowiska_dla_Gminy_Dobre_Miasto_na_lata_2022-2025_z_perspektywa_do_2030_roku/ (accessed on 10 March 2024).

- Swaryczewska, M. Sacrum i Profanum w Krajobrazie Kulturowym. Dziedzictwo Przestrzeni Sakralnej na Warmii; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Warmińsko-Mazurskiego: Olsztyn, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Drej, S. Święta Warmia; Pracownia Wydawnicza ElSet: Olsztyn, Poland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Antolak, M.; Szyszkowski, W. Funkcjonowanie krzyża przydrożnego w krajobrazie kulturowym Polski. Pr. Kom. Kraj. Kult. 2013, 21, 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Antonowicz, B. Dziedzictwo Kulturowe Warmii, Mazur, Powiśla: Stan Zachowania, Potencjały i Problemy; Warmińsko-Mazurskie Biuro Planowania Przestrzennego: Olsztyn, Poland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Drej, S.; Swajdo, J. Warmia i Mazury. Przewodnik; BOSZ: Olszanica, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Batyk, I.M. Dziedzictwo kulturowe Warmii. Infrastrukt. Ekol. Teren. Wiej. 2010, 7, 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Zagroba, M.; Pawlewicz, K.; Senetra, A. Analysis and Evaluation of the Spatial Structure of Cittaslow Towns on the Example of Selected Regions in Central Italy and North-Eastern Poland. Land 2021, 10, 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodziński, Z.; Kurowska, K. Cittaslow idea as a new proposition to stimulate sustainable local development. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zając, A.; Zając, M. (Eds.) Atlas Rozmieszczenia Roślin Naczyniowych w Polsce; Instytut Botaniki Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego: Krakow, Poland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Balon, J.; Krąż, P. Ocena jakości krajobrazu—Dobór prawidłowych jednostek krajobrazowych. In Identyfikacja i Waloryzacja krajobrazów—Wdrażanie Europejskiej Konwencji Krajobrazowej; Generalna Dyrekcja Ochrony Środowiska: Warsaw, Poland, 2013; pp. 58–63. [Google Scholar]

- ATPOL Topographic Map and Raster Map with a Grid of Squares. Available online: http://www.igipz.pan.pl/Regiony-geobotaniczne-zgik.html (accessed on 10 April 2016). (In Polish).

- Żarska, B. Ochrona Krajobrazu; Wydawnictwo SGGW: Warsaw, Poland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Malinowska, E. Wpływ atrakcyjności wizualnej krajobrazu na potencjał turystyczny Narwiańskiego Parku Narodowego i jego otuliny. Probl. Ekol. Kraj. 2010, 27, 277–285. [Google Scholar]

- Koc, J. Krajobraz Warmii. In Tożsamość Ziemi Warmińskiej—Monografia; Dziugieł-Łaguna, M., Łonyszyn, M., Pawelc, M., Eds.; Lidzbark Warmińsk: Lidzbark Warmińsk, Poland, 2005; pp. 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Bałdowski, J. Warmia, Mazury, Suwalszczyzna. Przewodnik; Muza SA: Warsaw, Poland, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Sierzputowski, A.; Juszczyński, M.; Drej, S. Tożsamości kulturowe Warmii i ich wpływ na kształtowanie przestrzeni geograficznej i kultury rolnej regionu. In Krajobraz Kształtowany Przez Kulturę Rolną; Młynarczyk, K., Ed.; Wydawnictwo UWM: Olsztyn, Poland, 2006; pp. 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Swaryczewska, M. Symboliczna Jerozolima w krajobrazie Warmii. Teka Kom. Arch. Urban. Stud. Krajobr. 2007, 3, 135–149. [Google Scholar]

- Jasiński, J. Dlaczego „Święta Warmia”. In Między Prusami a Polską. Rozprawy i Szkice z Dziejów Warmii i Mazur w XVIII–XX Wieku; Wydawnictwo Littera: Olsztyn, Poland, 2003; pp. 26–35. [Google Scholar]

- Pokropek, M. Osadnictwo i budownictwo. In Kultura Ludowa Mazurów i Warmiaków; Burszta, J., Ed.; Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich: Wroclaw, Poland, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Koreleski, K. Ochrona i kształtowanie terenów rolniczych w systemie kreowania krajobrazu wiejskiego. Infrastrukt. Ekol. Teren. Wiej. 2009, 4, 5–20. [Google Scholar]

- Suchenek, Z. Dobre Miasto. Skrawek Uroczej Warmii; Pracownia Wydawnicza „ElSet”: Olsztyn, Poland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kistowski, M. Eksterminacja krajobrazu Polski jako skutek wadliwej transformacji społeczno-gospodarczej państwa. In Studia Krajobrazowe a Ginące Krajobrazy; Chylińska, D., Łach, J., Eds.; Uniwersytet Wrocławski: Wroclaw, Poland, 2010; pp. 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Resolution No. XLI/238/2021, Uchwała Nr XLI/238/2021 Rady Miejskiej w Dobrym Mieście z Dnia 25 Marca 2021 r. w Sprawie Uchwalenia Miejscowego Planu Zagospodarowania Przestrzennego Fragmentu Miasta Dobre Miasto w Rejonie Ulic Olsztyńskiej, Cmentarnej, Jeziorańskiej i Granicy Administracyjnej Miasta. Available online: https://edzienniki.olsztyn.uw.gov.pl/WDU_N/2021/1827/akt.pdf (accessed on 13 March 2024). (In Polish)

- Urzqd Miejski w Dobrym Miescie. Available online: http://dobremiasto.e-mapa.net/ (accessed on 2 July 2024). (In Polish).

- Brumann, C.; Gfeller, A.É. Cultural landscapes and the UNESCO World Heritage List: Perpetuating European dominance. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2022, 28, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, F. Tangible heritage in archaeology. In Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 10489–10492. [Google Scholar]

- Tkocz, J. Organizacja Przestrzenna Wsi w Polsce; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego: Katowice, Poland, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Cymerman, R.; Falkowski, J.; Hopfer, A. Krajobrazy Wiejskie (klasyfikacja i Kształtowanie); Wydawnictwo ART: Olsztyn, Poland, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Raszeja, E. W poszukiwaniu ładu i autentyczności. Refleksje na temat kształtowania krajobrazu i architektury polskiej wsi. In Polska Wieś 2025—Wizja Rozwoju; Wilkin, J., Ed.; Fundusz Współpracy: Warsaw, Poland, 2005; pp. 191–197. [Google Scholar]

- Woźniak, M.; Cebulak, T.; Stec, S. Przestrzeń wiejska jako miejsce edukacji życia zgodnie z prawami natury. In Turystyka Wiejska a Edukacja; Sikora, J., Ed.; Wydawnictwo AR im. Augusta Cieszkowskiego: Poznań, Poland, 2007; pp. 244–251. [Google Scholar]

- Myga-Piątek, U. Kryteria i metody oceny krajobrazu kulturowego w procesie planowania przestrzennego na tle obowiązujących procedur prawnych. Probl. Ekol. Kraj. 2014, 19, 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Wańkowicz, W. Krajobraz—Wykorzystanie czy ochrona versus wykorzystanie i ochrona. Planowanie przestrzeni o wysokich walorach krajobrazowych. Teka Kom. Arch. Urban. Stud. Krajobr. 2012, 8, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhm, A. Planowanie w obszarach o wysokich walorach krajobrazowych. In Krajobraz a Turystyka; Andrejczuk, W., Ed.; Kom. Kraj. Kult. PTG: Sosnowiec, Poland, 2010; pp. 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Purchla, J. W stronę systemu ochrony dziedzictwa kulturowego w Polsce. Zarządzanie Publiczne 2010, 2, 69–82. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanowski, J. Kompozycja i Planowanie w Architekturze Krajobrazu; Ossolineum—PAN: Kraków, Poland, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Zagroba, M. The role of old towns in small Warmian towns in shaping the region’s cultural landscape. Acta Sci. Pol. Adm. Locorum 2023, 22, 289–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajerowski, T.; Biłozor, A.; Cieślak, I.; Senetra, A.; Szczepańska, A. Ocena i Wycena Krajobrazu. Wybrane Problemy Rynkowej Oceny i Wyceny Krajobrazu Wiejskiego, Miejskiego i Stref Przejściowych; Educaterra: Olsztyn, Poland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Pawłowska, K.; Swaryczewska, M. Ochrona Dziedzictwa Kulturowego. Zarządzanie i Partycypacja Społeczna; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego: Krakow, Poland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Polish Government. Act of 24 April 2015 on Amending Some Acts in Connection with the Strengthening of Landscape Protection Tools (Journal of Laws, 2015, Item 774); Internetowy System Aktów Prawnych (ISAP): Warsaw, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jedut, R. Geograficzne aspekty restrukturyzacji PGR wschodniej Polski. In Restrukturyzacja Państwowych Gospodarstw Rolnych w Świetle Doświadczeń Ogólnokrajowych; Wyższa Szkoła Inżynierska w Koszalinie—Polskie Towarzystwo Geograficzne: Koszalin, Poland, 1994; pp. 194–203. [Google Scholar]

- Niedźwiedzka-Filipiak, I. Wyróżniki Krajobrazu i Architektury Wsi Polski Południowo-Zachodniej; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Przyrodniczego we Wrocławiu: Wroclaw, Poland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Niedźwiedzka-Filipiak, I.; Filipiak, P. Wpływ stopnia modyfikacji zabudowy na wartość kulturową wsi w Polsce południowo—Zachodniej. In Wartościowanie w Ochronie i Konserwacji Zabytków; Szmygin, B., Ed.; Politechnika Lubelska: Warsaw, Poland; Lublin, Poland, 2012; pp. 151–160. [Google Scholar]

- Hermann, A.; Kuttner, M.; Hainz-Renetzeder, C.; Konkoly-Gyuró, É.; Tirászi, Á.; Brandenburg, C.; Allex, B.; Ziener, K.; Wrbka, T. Assessment framework for landscape services in European cultural landscapes: An Austrian Hungarian case study. Ecol. Indic. 2014, 37, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcinkowski, R. Intensywna zabudowa a ochrona walorów krajobrazu. Czas. Inżynierii Lądowej Sr. Archit. 2016, 63, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selman, P. Community participation in the planning and management of cultural landscapes. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2004, 47, 365–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazur, A.; Akincza, M. Edukacja społeczności Warmii i Mazur w procesie kształtowania wizerunku wsi. Teka Kom. Arch. Urban. Stud. Krajobr. 2012, 8, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subercaseaux, D.; Gastó, J.; Ibarra, J.T.; Arellano, E.C. Construction and metabolism of cultural landscapes for sustainability in the anthropocene. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Groups of Criteria | Description | Total Number of Points |

|---|---|---|

| A | Areas with outstanding cultural heritage value | >35 |

| B | Areas with very high cultural heritage value | 26–35 |

| C | Areas with high cultural heritage value | 16–25 |

| D | Areas with average cultural heritage value | 6–15 |

| E | Areas with low cultural heritage value | <6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mazur, A.; Kurowska, K.; Antolak, M.; Podciborski, T. Transformation of the Cultural Landscape in the Central Part of the Historical Region of Warmia in Poland. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6201. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16146201

Mazur A, Kurowska K, Antolak M, Podciborski T. Transformation of the Cultural Landscape in the Central Part of the Historical Region of Warmia in Poland. Sustainability. 2024; 16(14):6201. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16146201

Chicago/Turabian StyleMazur, Anna, Krystyna Kurowska, Mariusz Antolak, and Tomasz Podciborski. 2024. "Transformation of the Cultural Landscape in the Central Part of the Historical Region of Warmia in Poland" Sustainability 16, no. 14: 6201. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16146201

APA StyleMazur, A., Kurowska, K., Antolak, M., & Podciborski, T. (2024). Transformation of the Cultural Landscape in the Central Part of the Historical Region of Warmia in Poland. Sustainability, 16(14), 6201. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16146201