The Role of Collective Action and Identity in the Preservation of Irrigation Access in Dacope, Bangladesh

Abstract

1. Introduction

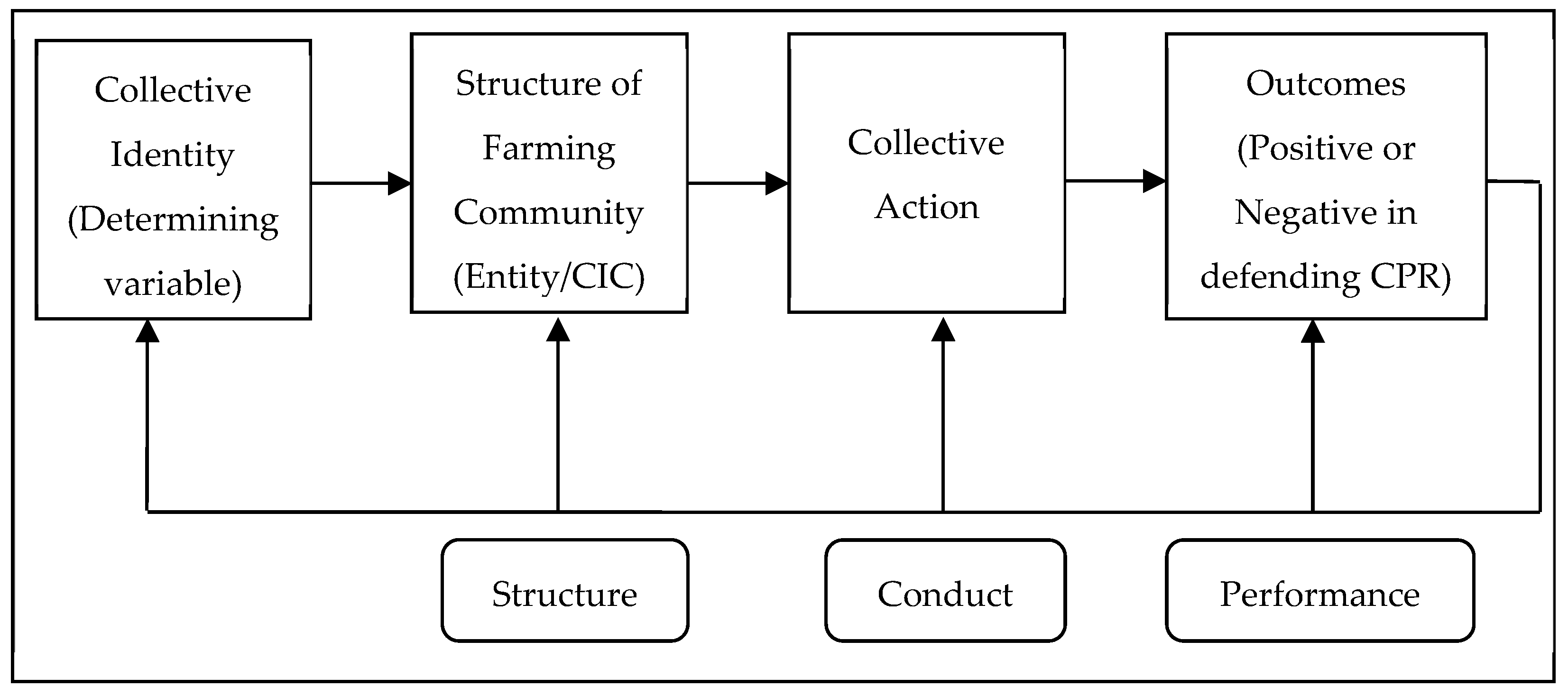

Theory of Collective Identity in Collective Action Situations

2. Methods

2.1. Ethnographic Setting

2.2. Description of the Study Area

2.3. Data Collection Methods and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Barriers to Adaptation: Land Tenure Issues and Salinity

3.2. Dacope Farmers’ Approach to Adaptation

3.3. Collective Identity among Dacope Farmers

“We are farmers by birth” he said. “I’ve been farming this land since I was a child. I watched my grandfather farm it, and then my father. I don’t know any other way to survive. I haven’t got the skills for a job in town, and even if I did, that’s not the life I want”.

“Saline water is harmful for watermelon cultivation, which is the major economic crop of ours. If we cannot grow it many families will go penniless, including me”.

Farmer A: “They (local authorities) do not have enough time to listen to us. Though we have elected them, and they get funds. But they do not use that fund in opening or closing the sluicegates. We used to collect money voluntarily and engage ourselves in these activities”.

Farmer B: “The person who was given charge by the BWDB to operate these sluice gates, never seen him. When I (Farmer B) personally tried to contact him via mobile, the other end said that it was wrong number”.

“After taking loans from local wealthy people, when we fail to repay them due to loss in agricultural failure, we move to other places. Most of us moved to the garments sector in Dhaka”.

4. Discussion

4.1. Land Tenure Insecurity

4.2. Constructing Collective Identity and Driving Collective Action

4.2.1. Function of CI: Fostering Belonging and Shared Responsibility (Local Level)

4.2.2. Facilitating Irrigation Management (Local Level)

4.2.3. Negotiating with Local Authorities and Empowerment

4.2.4. Building Resilience

4.3. Limitations and the Power of Land Tenure Insecurity

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

6. Future Directions

- Exploring alternative collective identity constructions that may empower the farmers in their fight against land grabbing.

- Investigating the role of external factors, such as NGOs and international organizations, in supporting the community’s efforts and advocating for their rights.

- Examining the potential for legal and policy frameworks to address the systemic issues of land ownership and resource management in the region.

- Delving deeper into community dynamics by expanding the study to include perspectives from other sectors within the community.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mainuddin, M.; Peña-Arancibia, J.L.; Karim, F.; Hasan, M.M.; Mojid, M.A.; Kirby, J.M. Long-Term Spatio-Temporal Variability and Trends in Rainfall and Temperature Extremes and Their Potential Risk to Rice Production in Bangladesh. PLOS Clim. 2022, 1, e0000009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniruzzaman, M.; Mainuddin, M.; Bell, R.W.; Biswas, J.C.; Hossain, M.B.; Yesmin, M.S.; Kundu, P.K.; Mostafizur, A.B.M.; Paul, P.L.C.; Sarker, K.K.; et al. Dry Season Rainfall Variability Is a Major Risk Factor for Cropping Intensification in Coastal Bangladesh. Farming Syst. 2024, 2, 100084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, S.; Hossain, M.M.; Huq, M.; Wheeler, D. Climate Change, Salinization and High-Yield Rice Production in Coastal Bangladesh. Agric. Resour. Econom. Rev. 2018, 47, 66–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, D.; Williams, S.; Jahiruddin, M.; Parks, K.; Salehin, M. Projections of On-Farm Salinity in Coastal Bangladesh. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2015, 17, 1127–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahtab, M.H.; Zahid, A. Coastal Surface Water Suitability Analysis for Irrigation in Bangladesh. Appl. Water Sci. 2018, 8, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkat, A.; Zaman, S.U.; Raihan, S. Distribution and Retention of Khas Land in Bangladesh; Human Development Research Centre (HDRC): Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Dewan, C. Simplifying Embankments. In Misreading the Bengal Delta; Climate Change, Development, and Livelihoods in Coastal Bangladesh; University of Washington Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; pp. 21–47. ISBN 978-0-295-74960-0. [Google Scholar]

- Kundo, H.K. Citizen’s Charter for Improved Public Service Delivery and Accountability: The Experience of Land Administration at the Local Government in Bangladesh. Int. J. Public Adm. 2018, 41, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Collective Action Theory. In The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Politics; Boix, C., Stokes, S.C., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 186–208. ISBN 978-0-19-956602-0. [Google Scholar]

- Meinzen-Dick, R.; Raju, K.V.; Gulati, A. What Affects Organization and Collective Action for Managing Resources? Evidence from Canal Irrigation Systems in India. World Dev. 2002, 30, 649–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N. Social Capital, Collective Action, and Adaptation to Climate Change. In Der Klimawandel; Voss, M., Ed.; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2010; pp. 327–345. ISBN 978-3-531-15925-6. [Google Scholar]

- Baland, J.-M.; Bardhan, P.; Bowles, S. Introduction. In Inequality, Cooperation, and Environmental Sustainability; Baland, J.-M., Bardhan, P., Bowles, S., Eds.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Mosimane, A.W.; Breen, C.; Nkhata, B.A. Collective Identity and Resilience in the Management of Common Pool Resources. Int. J. Commons 2012, 6, 344–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T.A.; Runge, C.F. The Emergence and Evolution of Collective Action: Lessons from Watershed Management in Haiti. World Dev. 1995, 23, 1683–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klandermans, B.; Sabucedo, J.M.; Rodriguez, M.; De Weerd, M. Identity Processes in Collective Action Participation: Farmers’ Identity and Farmers’ Protest in the Netherlands and Spain. Political Psychol. 2002, 23, 235–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klandermans, B. How Group Identification Helps to Overcome the Dilemma of Collective Action. Am. Behav. Sci. 2002, 45, 887–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashmore, R.D.; Deaux, K.; McLaughlin-Volpe, T. An Organizing Framework for Collective Identity: Articulation and Significance of Multidimensionality. Psychol. Bull. 2004, 130, 80–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polletta, F.; Jasper, J.M. Collective Identity and Social Movements. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2001, 27, 283–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stets, J.E.; Burke, P.J. Identity Theory and Social Identity Theory. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2000, 63, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groth, T.M.; Curtis, A.; Mendham, E.; Toman, E. The Development and Validation of a Collective Occupational Identity Construct (COIC) in a Natural Resource Context. J. Rural Stud. 2015, 40, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, C.; Breinlinger, S. Identity and Injustice: Exploring Women’s Participation in Collective Action. J. Community Appl. Psychol. 1995, 5, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latorre, S. Resisting Environmental Dispossession in E Ecuador: Whom Does the Political Category of ‘Ancestral Peoples of the Mangrove Ecosystem’ Include and Aim to Empower? J. Agrar. Chang. 2014, 14, 541–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalera-Reyes, J. Place Attachment, Feeling of Belonging and Collective Identity in Socio-Ecological Systems: Study Case of Pegalajar (Andalusia-Spain). Sustainability 2020, 12, 3388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinzen-Dick, R.; DiGregorio, M.; McCarthy, N. Methods for Studying Collective Action in Rural Development. Agric. Syst. 2004, 82, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melucci, A. Challenging Codes: Collective Action in the Information Age, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996; ISBN 978-0-521-57051-0. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, I. The Bengal Delta: Ecology, State and Social. Change, 1840–1943; Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies Series; 1. Publ.; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2010; ISBN 978-0-230-23183-2. [Google Scholar]

- Dewan, C.; Mukherji, A.; Buisson, M.-C. Evolution of Water Management in Coastal Bangladesh: From Temporary Earthen Embankments to Depoliticized Community-Managed Polders. Water Int. 2015, 40, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa Saroar, M.; Mahbubur Rahman, M.; Bahauddin, K.M.; Abdur Rahaman, M. Ecosystem-Based Adaptation: Opportunities and Challenges in Coastal Bangladesh. In Confronting Climate Change in Bangladesh; Huq, S., Chow, J., Fenton, A., Stott, C., Taub, J., Wright, H., Eds.; The Anthropocene: Politik—Economics—Society—Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 28, pp. 51–63. ISBN 978-3-030-05236-2. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, C.; Goodbred, S.; Small, C.; Gilligan, J.; Sams, S.; Mallick, B.; Hale, R. Widespread Infilling of Tidal Channels and Navigable Waterways in the Human-Modified Tidal Deltaplain of Southwest Bangladesh. Elem. Sci. Anthr. 2017, 5, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, S.; Geisler, C. Land Expropriation and Displacement in Bangladesh. J. Peasant Stud. 2012, 39, 971–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afroz, S.; Cramb, R.; Grunbuhel, C. Collective Management of Water Resources in Coastal Bangladesh: Formal and Substantive Approaches. Hum. Ecol. 2016, 44, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Political Economy of Institutions and Decisions Series Cambridge; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA; Melbourne, Germany, 1990; pp. xviii, 280. ISBN 0-521-37101-5. [Google Scholar]

- Dolšak, N.; Brondizio, E.S.; Carlsson, L.; Cash, D.W.; Gibson, C.C.; Hoffmann, M.J.; Knox, A.; Meinzen-Dick, R.S.; Ostrom, E. Adaptation to Challenges. In The Commons in the New Millennium: Challenges and Adaptation; Dolšak, N., Ostrom, E., Eds.; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003; ISBN 978-0-262-27186-8. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar, S.C. Bengal’s Southern Frontier, 1757 to 1948. Stud. Hist. 2012, 28, 69–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank Group. Doing Business 2016: Measuring Regulatory Quality and Efficiency; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-1-4648-0667-4. [Google Scholar]

- Vanclay, F. Social Principles for Agricultural Extension to Assist in the Promotion of Natural Resource Management. Aust. J. Exp. Agric. 2004, 44, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergami, M.; Bagozzi, R.P. Self-categorization, Affective Commitment and Group Self-esteem as Distinct Aspects of Social Identity in the Organization. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 39, 555–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinzen-Dick, R.S.; Pradhan, R. Legal Pluralism and Dynamic Property Right; AgEcon Search Agricultural & Applied Economics: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonvin, J.-M. Individual Working Lives and Collective Action. An Introduction to Capability for Work and Capability for Voice. Transf. Eur. Rev. Labour Res. 2012, 18, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallick, D.L. Chapter 5 Amplifying the Community Voices for Greater Access to Drinking Water in Bangladesh. In Community, Environment and Disaster Risk Management; Shaw, R., Thaitakoo, D., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2010; Volume 2, pp. 69–91. ISBN 978-1-84950-698-4. [Google Scholar]

- Seabrook, J. In the City of Hunger: Barisal, Bangladesh. Race Cl. 2010, 51, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A. Common Resources and Institutional Sustainability. In The Drama of the Commons; Ostrom, E., Dietz, T., Dolsak, N., Stern, P.C., Stonich, S., Weber, E.U., Eds.; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; p. 533. ISBN 978-0-309-08250-1. [Google Scholar]

| Components | Definition | Quotes from FGD | Appearances | Outcomes (Positive or Negative) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preserving Irrigation | Preserving Land Access | ||||

| Self-categorization | Self-identifying as a member of a farmer group. | Participants consistently referred to themselves as “we” instead of “they”, indicating a strong sense of shared identity and inclusivity within the group. | Clearly defined | Positive | Negative |

| Evaluation | An individual’s attitude, favorable or unfavorable, toward the farmer group. | “I am happy to be a farmer, and I know how important our work is to feed our family”. | High | Positive | Negative |

| Importance | The level of significance that a farmer holds within his overall self-perception. | “We are farmers by birthright! I’ve been farming this land since I was a child. I watched my grandfather farm it, and then my father. I don’t know any other way to survive. I haven’t got the skills for a job in town, and even if I did, that’s not the life I want”. | High | Positive | Negative |

| Attachment and sense of interdependence | The extent to which farmers perceive their own destiny as intertwined with that of the group. | “Saline water is harmful for watermelon cultivation, which is the major economic crop of ours. If we cannot grow it many families will go penniless, including me”. | High | Positive | Negative |

| Social embeddedness | The level of integration of farmer identity into an individual’s regular social interactions. | “They (local authorities) do not have enough time to listen to us. Though we have elected them, and they get funds. But they do not use that fund in opening or closing the sluicegates”. “We used to collect money voluntarily and engage ourselves in these activities”. | Low | Negative | Negative |

| Behavioral Involvement | The extent to which a farmer actively engages in action. | Farmers displayed strong behavioral involvement with their occupational identity, consistently wearing traditional farmer attire (Lungi and Gamcha). | High | Positive | Negative |

| Content and meaning | Self-descriptive endorsement of farmer group. | Based on assumption that this group is characterized b y a certain degree of dependency and precarious situation. “After taking loans from local wealthy people, when we fail to repay them due to loss in agricultural failure, we move to other places. Most of us moved to the garments sector in Dhaka”. | Low | Negative | Negative |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ashik Ur Rahman, M.; Beitl, C.M. The Role of Collective Action and Identity in the Preservation of Irrigation Access in Dacope, Bangladesh. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6279. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16156279

Ashik Ur Rahman M, Beitl CM. The Role of Collective Action and Identity in the Preservation of Irrigation Access in Dacope, Bangladesh. Sustainability. 2024; 16(15):6279. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16156279

Chicago/Turabian StyleAshik Ur Rahman, Md, and Christine M. Beitl. 2024. "The Role of Collective Action and Identity in the Preservation of Irrigation Access in Dacope, Bangladesh" Sustainability 16, no. 15: 6279. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16156279

APA StyleAshik Ur Rahman, M., & Beitl, C. M. (2024). The Role of Collective Action and Identity in the Preservation of Irrigation Access in Dacope, Bangladesh. Sustainability, 16(15), 6279. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16156279