Abstract

The overconsumption of clothing has detrimental impacts on society and the environment. For consumers, reducing consumption is complicated by the vital role that clothing plays in individual expression. This study examined the influence of personal values and clothing style confidence on consumers’ interest in upcycled clothing. An online Internet survey was used to gather data from a valid sample of 565 U.S. residents. Partial least squares structural equation modeling was used to analyze the data. Schwartz’s self-transcendence and self-enhancement values were modeled as antecedents to clothing style confidence (CSC), which is a multi-dimensional construct composed of five factors, including (1) style longevity, (2) aesthetic perceptive ability, (3) creativity, (4) appearance importance, and (5) authenticity. CSC was predicted to mediate the relationship between self-transcendence and self-enhancement values and interest in upcycled clothing, including the purchase of upcycled clothing and interest in learning how to upcycle clothing. Findings showed that CSC mediated the relationship between self-self-transcendence and self-enhancement values and interest in upcycled clothing, as predicted according to value–attitude–behavior theory. Results suggest that bolstering consumers’ confidence in personal style may provide intrinsic motivation for change, empowering individuals to embrace their personal style rather than follow fashion trends.

Keywords:

clothing products; fashion; style; values; sustainable consumption; self-expression; PLS-SEM 1. Introduction

There is a growing realization within the fashion industry that the “take-make-dispose” model is unsustainable [1,2]. The overproduction and overconsumption of clothing harms society and the environment [2,3,4]. “Fast fashion” practices produce continuous new collections at low prices that overstimulate consumer demand, leading to waste and the overconsumption of clothing [5,6,7]. It is estimated that more than USD 500 billion in value is lost annually by underutilized clothing and the lack of recycling [2]. Over half of all fast fashion clothing is disposed of within one year [1]. The average number of times clothing is worn before being discarded has decreased by 36% compared to two decades ago [2].

Sustainability has become a strategic concern for the apparel sector. Fashion companies increasingly prioritize sustainability initiatives and offer sustainable options in their product lines [7,8]. One of these options is upcycling, in which consumers or clothing brands repurpose or recreate new fashions from previously worn products [9,10]. For example, fashion brand Re/Done (https://shopredone.com, accessed on 4 June 2024) upcycles vintage Levi’s and Hanes clothing into modern styles, and the outdoor clothing brand Patagonia collects pre-owned clothing from its customers and recrafts them for resale (https://wornwear.patagonia.com, accessed on 4 June 2024). Although consumer interest in sustainable fashion is rising, especially among Gen Z and Millennial consumers [11,12], sustainable fashion options like upcycling have yet to become mainstream, as some consumers remain skeptical about costs and stylishness [13] or their ability to upcycle clothing themselves [14]. Fashion brands must understand what motivates consumers to engage in sustainable fashion consumption to effectively target sustainable fashion for broader consumer markets and ensure the success of their sustainability initiatives.

Only a handful of studies within the growing literature on sustainable fashion have examined consumers’ interest in upcycled clothing. Generally, findings show that upcycling appeals to environmentally conscious consumers [9,10,15]. However, these studies also suggest that pro-environmental values are not the primary driver for consumers’ interest in upcycling. Consumers were also motivated by opportunities for individualistic self-expression, self-enhancement, and personal characteristics like creativity and fashion consciousness. Similar findings appear in studies with sustainable fashion consumers who report that “clothing style confidence”, defined as “confidence about the individual way people express themselves with clothing and accessories” [16] (p. 554), is the characteristic underlying their behaviors [13,17,18]. These exploratory findings offer new insights into consumers’ motivations for sustainable clothing consumption. However, more research is needed to test the influence of clothing style confidence on interest in upcycling and determine its antecedents.

The central research question driving this investigation is as follows: what is the relationship between personal values, clothing style confidence, and interest in upcycling? This study examined how personal values (i.e., self-transcendence and self-enhancement values) and clothing style confidence operate together to influence consumers’ interest in upcycled clothing, including purchasing upcycled clothing and learning how to upcycle clothing. A greater understanding of the role of personal values and clothing style confidence in fostering consumers’ interest in upcycling may suggest how fashion brands and retailers can identify and attract more potential target markets for upcycled clothing products. It may also suggest new services like personal stylists to help consumers develop confidence in their clothing style, or upcycling design specialists to assist consumers who want to upcycle apparel in their wardrobe. For example, upcycleDZINE (https://www.upcycledzine.com, accessed on 4 June 2024) features over 400 upcycle designers, including small businesses, who share their upcycling ideas and offer upcycled products for sale.

The paper is organized as follows. The background describes the theoretical framework supporting the study hypotheses, which is based on Schwartz’s theory of basic human values [19,20,21], the hierarchical value–attitude–behavior model [22], and psychological models for understanding people’s motives for pursuing fashion [23]. The background also introduces the literature to support the study hypotheses and presents the conceptual model. Next, a description of the study methods is presented, which utilized an Internet survey administered to a valid convenience sample of 565 U.S. adults between the ages of 25 and 65 purchased from Prolific. After presenting the findings, the paper concludes with a discussion of the results, their theoretical and practical implications, the study’s limitations, and suggestions for future research.

2. Theoretical Framework and Support for Study Hypotheses

2.1. Theory of Basic Human Values and the Value–Attitude–Behavior Model

Values are viewed as enduring beliefs about desired end-states or modes of conduct that guide human behavior [20,24,25]. Values can be guiding principles in the life of a person or a group. Personal values reflect individual conceptions about what is important to that person, while cultural values reflect what tends to be important to groups. One of the most influential theories of personal values is Schwartz’s theory of basic human values. Schwartz and Bilsky [19] developed a theory of how personal values are interrelated within a universal value system, or how the clustering of values are integrated or closely connected. Following an analysis of data on 56 values obtained from samples across 44 countries, the researchers identified ten universal values, which they represented as value clusters located within a two-dimensional circumplex model. In the theory, values in opposite axes are hypothesized to be conflicting, as behaviors that satisfy one goal may come at the expense of the opposing value. The subsequent testing of this theory in multiple countries supports the near-universal organization of values along these motivational dimensions and the hypothesized interrelationships between oppositional value clusters [20,21]. The first dimension, “openness to change/conservation” represents conflict between the desire for new experiences versus tradition and conformity. The second dimension, “self-enhancement/self-transcendence”, represents the conflict between individual or egoistic concerns and concerns for others and nature. Schwartz [20] designated these two dimensions as higher-order value clusters that differentiate whether an individual’s primary motivation is to promote self-interests (i.e., self-enhancement) or to promote the welfare of society and the environment (i.e., self-transcendence).

Personal values are theorized to influence attitudes and behaviors [22,26]. Values are central to one’s self-concept [24], and as central components of belief systems, they represent energizing forces for expressing personal goals [27]. Conversely, attitudes are oriented toward specific stimuli and are seen as expressions of or subordinate consequences of values in the hierarchical value–attitude–behavior model [22]. Behaviors are also systematically related to values in that people are prone to act in a self-congruent manner with their value systems [24]. However, the influence of personal values on behavior is theorized not to be as strong as more proximal sources of motivation, such as attitudes [22,28]. According to the hierarchical value–attitude–behavior model of value-motivated behavior [22], influence should flow sequentially from highly abstract values to value-relevant attitudes to specific behaviors within any given context. For instance, in a test of the theory, Homer and Kahle [22] found that values predicted consumers’ attitudes toward natural foods and that these attitudes, in turn, predicted shopping behaviors for natural foods. Attitudes toward natural foods mediated the relationship between values and shopping behaviors.

A handful of studies have examined the relationship between personal values and sustainable clothing behaviors. All support a positive influence of pro-environmental or socially conscious values on consumers’ use or purchase of sustainable clothing products. Studies also reveal that egoistic values or factors associated with self-interests can positively influence consumers’ attitudes and behavior toward sustainable clothing products. For instance, Bhatt et al. [10] found that environmental concern positively influenced consumers’ interest in learning upcycling techniques and purchasing upcycled clothing products. However, individual concerns such as consumer creativity and fashion consciousness, or awareness, also influenced consumers’ interest in upcycling. Park and Lin [15] found that self-expressiveness positively influenced consumers’ interest in purchasing upcycled fashion in addition to environmental concerns. However, the same was not true for interest in purchasing secondhand goods. They attributed these results to the perception that upcycled fashion products are more innovative or unique than recycled goods sold in secondhand clothing stores. Qualitative research with sustainable fashion consumers reveals similar findings. Lindblad and Davies [29] used a laddering technique with 39 sustainable fashion consumers to uncover values driving their behavior. They found that both self-transcendence and self-enhancement values, especially those associated with accomplishment, individuality, and self-esteem, motivated sustainable clothing behaviors. Personal values have also been shown to influence value-relevant or clothing attitudes. In another laddering study with 98 ethical clothing consumers, Jägel et al. [30] discovered multiple values were positively associated with ethical and sustainable attitudes toward clothing. These included not only environmental and altruistic values, but also individual motives related to values of money and personal image. In summary, research shows that consumers who purchase sustainable clothing products do so to express a complex mix of end-goals, including concern for the environment, altruism, clothing longevity, self-expression, creative satisfaction, and attitudes toward appearance.

2.2. Psychological Models of Fashion and Clothing Style Confidence

Socio-psychological theories of fashion theorize that individuals use clothing to construct and express self-identity and to communicate identities to others [31,32]. The fashion theory literature proposes that diverse psychological motivations underlie people’s clothing choices and fashion consumption orientations. These varied motivations can be classified into two basic models: individualism-centered models and conformity-centered models [23]. Individualism-centered models [33] emphasize motives related to self-enhancement and individuality, such as distinctiveness, prestige, excitement, rebellion against convention, values, attitudes, and creative expression. Conformity-centered models emphasize how social pressures to conform to prevailing styles of dress influence style choices [34]. Research shows that individuals interested in clothing are more likely to have a heightened awareness of clothing’s social meanings and ascribe higher importance to personal appearance [33,35].

The body becomes a malleable form of self-expression through clothing and other forms of body adornment, such as tattoos or hairstyles [33]. The symbolic-interactionism theory of fashion [36] describes how self-identity is constructed through the appearance management process. Individuals convey aspects of self to others through their clothing selections, which represent external symbols of shared meaning that express values, feelings, and beliefs understood within social contexts [37]. Social interactions provide information that the person then uses to self-reflect on others’ inferred perceptions of their self-symbolizing with clothing. This self-reflection process can fortify internal self-identity or prompt modifications in clothing selections that enable the person to reflect their desired self-image more closely.

Social approval is a powerful force motivating the growth of fashion trends. The accelerated pace of fashion change epitomized by fast fashion contributes to clothing overconsumption [38]. Many consumers feel compelled to conform to current fashion trends to maintain a trendy self-image. These consumers, sometimes called “fast fashion” or “fashion-oriented” consumers, are more outward-oriented, using clothing for social positioning [39,40]. Fashion-oriented consumers are more aware of fashion trends and make more frequent clothing purchases to keep up with increasingly short-lived fashion trends [40]. Conversely, “slow fashion” or “style-oriented” consumers are less concerned with trendiness [39]. Instead, these consumers are motivated to use clothing for self-expression and value authenticity, uniqueness, and quality over quantity [40,41]. Style-oriented consumers want to look and feel good in their clothing, but their motives are internally rather than externally driven. Research shows they are less materialistic and care more about clothing longevity [40].

Clothing style confidence, or confidence in one’s ability to use clothing to express oneself using clothing [16], has been viewed by some scholars as a potential motivator for engaging in sustainable clothing consumption behaviors. Cultivating a unique, personal clothing style frees consumers from the need to continually monitor fashion trends. Because self-identity evolves more slowly through self-awareness, style confidence may promote mindful consumption behaviors that increase clothing longevity, such as upcycling [41]. Fletcher and Grose [42] argue that a lack of self-confidence in expressing identity through clothing leads consumers to blindly follow fashion dictates without considering the environmental impact of their excessive clothing consumption. Bly and her colleagues [17] were among the first to uncover a positive relationship between sustainable fashion behaviors and personal style confidence. Participants in their qualitative investigation described how their sustainable clothing behaviors, like upcycling their own clothing or buying secondhand clothing, facilitated self-expression and contributed to their happiness and well-being. Two traits frequently cited by sustainable fashion consumers as essential for developing personal style were creativity and self-awareness. Cho et al. [18] also identified style-oriented consumption as a potential avenue for promoting sustainable clothing consumption. In an online survey with 586 consumers, Cho et al. [18] found that style consumption was motivated by ecologically conscious consumption, fashion consciousness, and frugal apparel consumption. In turn, style consumption was positively associated with purchasing environmentally friendly apparel.

Only a handful of studies have quantitatively studied personal style and its influence on sustainable clothing. This is partly because, until recently, the concept was vaguely defined, and valid measures did not exist. Joyner Armstrong et al. [16] conceptualized clothing style confidence (CSC) as a multidimensional attitude representing people’s confidence in expressing personal style through clothing choices. These authors developed a 22-item scale for measuring CSC composed of five affective, cognitive, and behavioral attitudinal dimensions: (1) style longevity, or preference for timeless styles; (2) aesthetic perceptual ability, or knowledge about what looks good on them; (3) creativity, or interest in experimenting with one’s wardrobe; (4) appearance importance; and (5) authenticity, or how well their clothing style reflects their “true” self. Initial scale items were developed through interviews with a small sample of individuals who self-identified as “style confident”. Subsequent versions of the scale were tested in Internet surveys conducted with two different samples of adults to purify items and validate the scales’ nomological and predictive validity. Each dimension of CSC was significantly correlated with two criterion behaviors associated with sustainable clothing consumption: wardrobe engagement (i.e., knowing what is in one’s wardrobe and keeping it organized) and wardrobe preservation (i.e., paying attention to the condition of one’s wardrobe). The scale authors proposed that CSC would likely predict other sustainable clothing behaviors, but they did not empirically validate this claim.

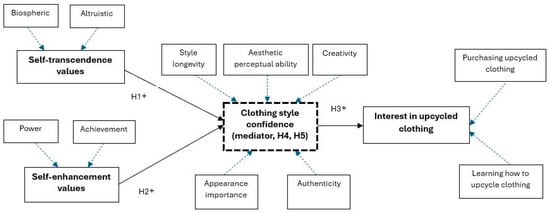

Based on the hierarchical value–attitude–behavior theory described in the previous section and the prior literature reviewed above, CSC is expected to mediate the relationship between personal values for self-transcendence and self-enhancement and consumers’ interest in upcycled clothing. These expectations are formally stated below in the study hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Self-transcendence values will positively influence clothing style confidence.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Self-enhancement values will positively influence clothing style confidence.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Clothing style confidence will positively influence interest in upcycled clothing.

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Clothing style confidence will mediate the relationship between self-transcendence values and interest in upcycled clothing.

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

Clothing style confidence will mediate the relationship between self-enhancement values and interest in upcycled clothing.

The conceptual model for the study appears below in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection and Sampling

An Internet survey was conducted with a convenience sample of 600 U.S. residents between the ages of 25 and 65 purchased from Prolific (www.prolific.com, accessed on 4 June 2024). The study objective was to test theoretical relationships, not to generalize clothing behavior to the general population. Therefore, sampling methods sought a representative sample of adult clothing buyers. The range of ages purposefully excluded consumers under 25 as they may not have enough life experience or self-awareness to develop a personal clothing style. The sample was evenly split by gender (males/females) to ensure the sample represented the attitudes of both men and women. Men are often underrepresented in clothing studies. According to Mintel [43], both males and females use clothing for self-expression and gain confidence by being well-dressed and comfortable. Respondents were paid at a rate of USD 12 per hour for completing a 20 min survey. The author’s Institutional Review Board approved the study before data collection. Informed consent was obtained from all study participants. After obtaining their consent, respondents were given the following definition of clothing to use when answering questions: “This survey contains questions about your attitudes and behaviors toward clothing for yourself, not others. For these questions, ‘clothing’ is defined as any apparel that can be worn on the human body, including jewelry, shoes, hats, scarves, and other objects”. Two instructional attention-check questions (e.g., Please respond ‘slightly agree’ to this question) were embedded in multi-item question blocks at different points in the survey for response quality assurance.

The valid sample number was 565 after removing cases that failed the attention checks or contained missing demographic data and following data clean-up to detect univariate and multivariate outliers before data analysis [44]. The minimum sample needed for partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) is calculated based on the statistical power of model path estimates, typically aimed at a power level of 80% and significance level of 5% [45]. The sample size for this study exceeded the minimum of 132 calculated by G*Power 3.1 for a desired effect size (f2) of 0.15 [46]. In addition, post hoc minimum sample sizes were calculated using the PLS-SEM algorithm for each path coefficient in the structural model, as recommended by Hair et al. [45] (p. 26). These results indicated the sample size exceeded a minimum of 107 needed for the largest path coefficient to achieve a power level of 90% at a significance level of 1%. Women made up 49.9% of the sample, and men made up 50.1%. The mean age was 39.6 (s = 10.92). Most were college graduates (47.1%). The median household income was between USD 50,000 and USD 74,999. Most respondents were white (76.6%), with 13.8% identifying as black and 10.3% as Asian. While lack of diversity is an issue with all crowdsourcing samples, Prolific samples have been shown to be more diverse and produce higher quality data than competing sample sources, including Amazon’s MTurk [47,48].

3.2. Measures

All constructs in the model were measured using previously validated multi-item scales. As shown in Figure 1, the conceptual model has four higher-order multidimensional constructs—self-transcendence, self-enhancement, clothing style confidence, and interest in upcycled clothing—each of which was measured using subscales, 11 in total, representing the construct’s lower-order dimensions. The subsections below provide a detailed description of each measure.

3.2.1. Personal Values

Of the two main dimensions of personal values in Schwartz’s value system [19,20,21], the dimension most relevant for the current study is self-transcendence versus self-enhancement. The self-transcendence value cluster was formed by two three-item subscales, one for biospheric values and one for altruistic values representing concern for nature and concern for others, respectively. Items for these subscales were taken from Stern et al.’s Brief Inventory of Values (BIV) [49]. The self-enhancement value cluster was also formed by two three-item subscales, one to represent power and influence values and one to represent achievement values. The power/influence subscale came from the BIV [49]. The achievement subscale was based on items in the modified version of the SVS [50]. Respondents rated the importance of each of the six value items as a guiding principle in their life on a 9-point scale from 0 = “not important” to 8 = “of supreme importance”.

3.2.2. Clothing Style Confidence

Clothing style confidence (CSC) was measured with the 22-item multi-dimensional scale developed by Joyner Armstrong et al. [16]. The CSC includes five subscales, one for each dimension. The dimensions for style longevity, aesthetic perceptual ability, and authenticity were each measured with four-item subscales. The dimensions for creativity and appearance importance each contained five items. Instructions asked participants to indicate how much they agreed or disagreed with each statement as it reflected their personal clothing style on a scale from 1 to 7, where 1 = “strongly disagree” and 7 = “strongly agree”.

3.2.3. Interest in Upcycled Clothing

Respondents were provided with the following definition of upcycling [10] prior to viewing the measures: “Upcycling is the practice of repurposing or remaking items to be of the same or greater quality than the original”. Interest in upcycled clothing was measured using two subscales developed by Bhatt et al. [10]. The first dimension, interest in purchasing upcycled clothing, was measured using a five-item scale. Interest in learning how to upcycle clothing was measured by four items also developed by Bhatt et al. [10]. All items were measured on 5-point Likert scales from 1 = “strongly disagree” to 5 = “strongly agree”.

3.3. Data Analysis Procedures

The method used for data analysis was partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) with SmartPLS 4.0 [51]. PLS-SEM differs from covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM) regarding how model parameters are estimated [45,52]. CB-SEM treats the model constructs as common factors, while PLS-SEM treats constructs as composites based on total variance. Composite scores are formed by linear combinations of the values of all standardized indicators associated with a particular latent construct such that it maximizes the total variance explained by the model’s causal–predictive relationships. Therefore, PLS-SEM is superior to covariance-based structural equation modeling when the primary research objective is the prediction and explanation of target constructs [45], which was the aim of this research. PLS-SEM is also better for analyzing complex models, like those with multiple constructs, indicators, and/or model relationships, and those involving advanced mediation analysis with latent variables [53,54]. This is because, unlike CB-SEM, PLS-SEM can facilitate these complex analyses while accounting for measurement error in the indicators, and it can do so with smaller samples.

Model evaluation involved a two-step process with separate assessments of the measurement and structural models according to guidelines recommended by Hair et al. [45]. In step one, the reliability and validity of the lower-order and the higher-order construct measures were examined, separately, using confirmatory composite analysis (CCA), a systematic methodological process for confirming measurement models in PLS-SEM [53]. Because PLS-SEM accounts for the total variance in the measures, CCA accomplishes the goals of both exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis in CB-SEM. Because the estimation of latent constructs in PLS-SEM always depends on their relationship with dependent variables in the network, model goodness-of-fit indices are not typically reported [53]. In step two, the structural model was evaluated. In this stage, the significance and relevance of the model’s hypothesized pathways were tested with nonparametric bootstrapping procedures that estimated coefficients within a 95% confidence interval for hypothesized direct and indirect pathways and their standard errors. Confidence intervals that did not include zero supported a conclusion of statistical significance. The evaluation of the structural model also included an assessment of the predictive validity of variables on the model’s endogenous constructs.

4. Results

4.1. Confirmatory Composite Analysis of Measurement Model

Because the model contained four higher-order multidimensional constructs along with their lower-order dimensions, a disjoint two-stage approach was used to estimate and validate the measurement model [55,56]. In the first stage of the disjoint two-stage approach, the 11 lower-order variables were assessed for measurement properties. Latent variable composite scores for the eleven lower-order variables forming the model’s four higher-order structural constructs were obtained from a path analysis that connected each lower-order dimension to all other variables as specified in the model. These latent variable composite scores then became the indicators for their respective higher-order constructs. In the second stage, the higher-order constructs were then tested separately for their measurement properties. Once their measurement properties were affirmed, the four higher-order constructs were used to create a more parsimonious model for testing the structural model’s hypothesized paths and mediation effects [56].

Table 1 presents the indicator items, outer measurement loadings, Cronbach’s α, composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE) values for all lower-order constructs. Standardized outer loadings for indicators were within or near the recommended range of 0.70 to 0.95 [45] for demonstrating item reliability. For all constructs, Cronbach’s α and composite reliability (CR) exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.70 for establishing construct reliability. The average variance extracted (AVE) exceeded the 0.50 criterion for convergent validity. Table 2 provides reliability and validity assessments for the higher-order constructs. Loadings for dimensions representing each higher-order construct exceeded the threshold of 0.70 needed for establishing reliability. Cronbach’s α and CR values were above 0.70, and AVE exceeded the threshold of 0.50, demonstrating reliability and convergent validity, respectively, for all higher-order measures in the structural model.

Table 1.

Reliability and validity assessment of lower-order constructs.

Table 2.

Reliability and validity assessment of higher-order constructs.

The recommended method for establishing discriminant validity in PLS-SEM is the heterotrait–monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT) [45,57]. The traditional Fornell–Larcker criterion [58] can also be used to assess discriminant validity, but it is less accurate when the indicator loadings of constructs vary only slightly. HTMT is the ratio of between-trait correlations to the within-trait correlations, or the mean of all correlations of indicators across all constructs relative to the mean of the average correlations of indicators within constructs. Henseler et al. [57] recommend a threshold value of 0.90 or below for establishing discriminant validity. The HTMT matrix for all lower model constructs appears in Table 3. Only one correlation, the one between subscales for power and achievement, exceeded this standard with a value of 0.95. This was not problematic, however, as these variables form indicators for the same higher-order construct, i.e., the self-enhancement value. A Fornell–Larcker assessment of the lower-order constructs was conducted along with the HTMT. The criterion for the Fornell–Larcker test is that the square root of each construct’s AVE should be greater than its correlation with any other construct in the model. This matrix appears in Table 4. As shown in the main diagonal, the square root of the AVE values exceeded the correlations of each lower-order construct with all other lower-order constructs in the model. Unlike the HTMT assessment, the Fornell–Larcker test demonstrates an acceptable level of discriminate validity between the power and achievement subscales.

Table 3.

HTMT matrix for lower-order constructs.

Table 4.

Fornell–Larcker matrix for lower-order constructs.

Table 5 and Table 6 repeat these discriminant validity assessments for the higher-order constructs. The HTMT matrix for higher-order constructs in Table 5 shows none of the average construct correlations exceeded the threshold value of 0.90 for discriminate validity. As shown in Table 6, the Fornell–Larcker matrix also supports discriminate validity, as the square root of the AVE for each higher-order construct exceeded the construct’s association with other higher-order constructs in the structural model.

Table 5.

HTMT matrix for higher-order constructs.

Table 6.

Fornell–Larcker matrix for higher-order constructs.

4.2. Structural Model Assessment and Hypothesis Results

Because PLS-SEM is similar to multiple regression analysis, the first step in the structural model assessment is to evaluate variables in the structural model for evidence of collinearity. Variance inflation factors (VIFs) for each set of predictor constructs in the inner model paths were below 2.0, well below the conservative threshold of 3.0 recommended by Hair et al. [45].

The assessment of the structural model entailed an evaluation of the direct and indirect effects of hypothesized relationships among constructs in the conceptual model that appear in Figure 1. The results appear in Table 7. First, the direct pathways, as predicted by the value–attitude–behavior theory, were tested. H1 predicted that self-transcendence values would positively influence clothing style confidence (CSC). The direct path between self-transcendence values and CSC was significant (β = 0.275, t = 7.098, p < 0.001), supporting H1. H2 predicted that self-enhancement values would positively influence CSC. The direct path between self-enhancement values and CSC was also significant (β = 0.261, t = 5.326, p < 0.001), supporting H2. H3 predicted that CSC would positively influence interest in upcycled clothing. The results support H3 (β = 0.287, t = 6.123, p < 0.001).

Table 7.

Bootstrap mediation analysis of structural model paths.

Next, H4 and H5 predicted that CSC would mediate the relationships between personal values and interest in upcycling. A mediation analysis was conducted using Zhao et al.’s [59] multi-step procedure for interpreting mediation effects described by Hair et al. [45] for PLS-SEM. The first step in this process addresses the significance of the indirect effect via the mediating variable. If significant, the mediation effect of the intervening variable, in this case CSC, is supported. The second step of this process examines the significance of the direct relationship between the independent and dependent variables to determine if the mediation effect is partial or full. If the direct path is also significant, the mediation is considered partial. If insignificant, the intervening variable’s mediation effect is considered full.

The results for the mediation (indirect path) of values through CSC appear in the bottom section of Table 7. The indirect path between self-transcendence values and interest in upcycled clothing via CSC was significant (β = 0.079, t = 4.70, p < 0.001). Therefore, H4 is supported. Because the direct path between self-transcendence values and interest in upcycling was also significant (β = 0.350, t = 8.633, p < 0.001), the mediating influence of CSC was partial. Last, H5 predicted that CSC would mediate the relationship between self-enhancement values and interest in upcycled clothing. H5 was also supported. The results indicate that CSC fully mediated the relationship between self-enhancement values and interest in upcycled clothing. The indirect path via CSC was positive and significant (β = 0.075, t = 3.995, p < 0.001). However, self-enhancement values were not directly related to interest in upcycled clothing (β = −0.064, t = 1.521, p = 0.128, ns).

4.3. Assessment of the Explanatory and Predictive Power of the Structural Model

The final stage in PLS structural model assessment involves examining the explanatory and predictive power of the model’s exogenous (i.e., predictor) constructs on their respective endogenous (i.e., dependent) variables. First, f2 effect sizes were obtained for each of the direct paths in the model. These appear in the far-right column of Table 7. Values between 0.02 and 0.14 are considered small, those between 0.15 and 0.34 are considered medium, and values of 0.35 or above are considered large effects [60]. The strongest relationship was that between self-transcendence values and interest in upcycled clothing. However, relatively small effect sizes are not uncommon in consumer psychology studies, partly because most consumer-relevant phenomena are determined by multiple influences and partly because most consumer research seeks to uncover non-obvious influences as part of the discovery process [61].

Table 8 presents the R2 values or variance explained for each endogenous variable in the model. Chin [62] proposes guidelines of 0.67, 0.33, or 0.19 for substantial, moderate, or weak R2 values, respectively. The R2 values for both endogenous constructs were statistically significant (p < 0.001) but relatively small. Notably, the model explained a small to moderate level of variance (R2 = 26%) in the primary dependent variable, i.e., interest in upcycled clothing. Last, a blindfolding procedure was used to establish the predictive relevance of the endogenous constructs. Using construct cross-validated redundancy, Q2 values for all endogenous constructs exceeded zero, indicating the model has predictive validity [53]. These values also appear in Table 8.

Table 8.

Explained variance and predictability of the model’s endogenous variables.

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Discussion

Previous studies have identified values and personal style as important influences on sustainable fashion consumption [17,18,29,30]. However, the concept of personal style orientation was not wholistically defined in the literature, and no validated measures existed to confirm its influence on sustainable clothing consumption. This limitation was addressed when Joyner Armstrong et al. [16] proposed a multidimensional attitudinal construct to represent personal style orientation, which they called “clothing style confidence”. Joyner Armstrong et al. [16] defined clothing style confidence (CSC) as a person’s confidence in the individual way they express themselves with clothing and developed an empirically validated 22-item scale to measure it. The scale authors proposed that the CSC scale could be used to empirically confirm linkages between clothing style confidence and a variety of sustainable fashion behaviors. This study’s findings support such a linkage to interest in upcycled clothing products.

This study examined how personal values are associated with confidence in clothing style and how they operate in conjunction to positively influence consumers’ interest in upcycled clothing products. Self-transcendence, representing concern for the environment, and concern for others, had a direct positive influence on interest in upcycling, which is a finding that is consistent with the prior literature [10,15,18]. Self-enhancement values, representing egoistic concerns including wealth, influence, and achievement, were not directly related to interest in upcycled clothing. However, both of these opposing personal values in Schwartz’s [19,20,21] value system were positively related to clothing style confidence, which represents a concern for appearance as well as choosing and wearing clothing that suits one’s personal style and can be worn for a long time. Clothing style confidence, in turn, positively influenced interest in upcycled clothing, which provides empirical support for proposed relationships between clothing style confidence and sustainable clothing choices and practices [16,63].

In accordance with value–attitude–behavior theory [22], findings showed that clothing style confidence mediated the relationship between self-transcendence and self-enhancement values and interest in upcycled clothing. CSC partially mediated the relationship between self-transcendence values and interest in upcycled clothing, which demonstrates a complementary influence of both factors on upcycling. CSC fully mediated the relationship between self-enhancement values and interest in upcycled clothing, which explains results from prior research showing mixed influences on people’s interest and engagement in sustainable clothing purchases and consumption practices [29,30]. Overall, findings suggest that people’s confidence in their ability to express themselves through their distinctive clothing style creates a conduit through which people feel empowered to express their personal values in a self-directed manner that does not depend on fashion system trends.

5.2. Theoretical and Practical Implications

This study offers important theoretical contributions to the literature on sustainable clothing consumption. First, this study demonstrates how the value–attitude–behavior hierarchy model [22] helps to explain the influence of values on sustainable clothing behaviors and intentions. Qualitative research conducted by Lundblad and Davies [29] and Jägel et al. [30] demonstrated the importance of biospheric or self-transcendence motives to sustainable fashion consumers. However, these studies also found that sustainable fashion consumers were motivated by internally oriented egoistic or self-enhancement values, like feelings of accomplishment and a greater sense of well-being. From a theoretical perspective, when two opposing higher-order values drive consumers’ behavior, like self-transcendence versus self-enhancement, Schwartz’s theory of dynamic value relations suggests the potential for conflict or the need to compromise [19,20,21]. This study’s findings show that both self-transcendence and self-enhancement values are antecedents of clothing style confidence, a multidimensional attitudinal construct for assessing people’s confidence in their ability to express individuality through clothing purchase and wear. The mediating influence of clothing style confidence makes these seemingly opposing goals compatible. Clothing style confidence promotes sustainable clothing goals, like seeking styles that last instead of chasing transient fashion trends, without sacrificing important individual goals and meanings associated with clothing, including creativity, self-expression, and appearance. Future research could investigate other attitudinal constructs that might mediate the influence of conflicting or mixed values or goals on sustainable clothing behaviors. For instance, research might explore the relationship between aesthetic attitudes, values, and interest in upcycling. Self-esteem is another attitude, one that reflects one’s attitude toward self, that may reconcile conflicting egoistic and biospheric values and their influence on sustainable or socially responsible consumer behaviors, such as making charitable donations of clothing.

This study also contributes to future research utilizing the construct of clothing style confidence. This is one of the first studies to examine the CSC scale with a relatively large sample of both males and females. The scale exhibited good measurement properties, and all five dimensions contributed significantly and uniquely to the higher-order construct. Also, the scale performed equally well with both men and women. The findings confirm the scale authors’ proposition that clothing style confidence is positively associated with sustainable clothing consumption [16], specifically the purchase of environmentally friendly clothing and upcycled clothing and interest in learning how to upcycle clothing. This study provides a demonstration of how the scale can be modeled as a higher-order construct in structural equation models to reduce the number of paths and create a more parsimonious model, which may be helpful for future research using the CSC scale.

The findings also provide practical applications for marketing managers and retail fashion brands. First, the close association between clothing style confidence and sustainable clothing behaviors suggests that incorporating attempts to appeal to or promote clothing style confidence may be an effective way for fashion brands to persuade a broader segment of consumers to adopt sustainable clothing behaviors. For example, brands might consider ways to allow consumers to indicate or describe their personal style when shopping online for particular products. This would enable consumers to customize their shopping searches toward product styles they know look good on them, which in turn might improve their shopping experience and potentially help retailers avoid costly returns. Retailers might offer revenue-generating services like personal shoppers or style consultants for consumers who are not style-confident. Alternatively, free online “style bots” might be activated upon request to help consumers who need help finding products that fit their needs and values. Because the findings demonstrate that personal style helps consumers express their personal values, retailers might utilize self-expressiveness and authenticity as appeals for promoting sustainable clothing products. Fashion brands could also encourage consumers to share their own experiences and tips for upcycling clothing made by the brand on a community website. For instance, IKEA fans can share their ideas for transforming old IKEA furniture into new home décor items on the IKEA Hackers website (https://ikeahackers.net, accessed on 4 June 2024). Research shows that consumers develop stronger emotional attachments to goods they have upcycled [64]. Therefore, offering consumers a community space where they can share upcycling ideas with others and learn tips on how to upcycle clothing may help to promote upcycling and increase consumers’ attachment to the brand.

This study also suggests how public policymakers can promote the sustainable consumption of clothing or other products by bolstering consumers’ confidence in abilities needed to repurpose or upcycle goods. For example, communities could sponsor upcycling workshops that teach people how to explore their own creativity or offer classes on sewing and other skills needed for upcycling projects. McEachern et al. [65], in a study in which they exposed focus group participants to interactive upcycling workshops, report that participants enjoyed learning upcycling techniques and felt empowered to think about ways to use their own clothing longer.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Like most studies, this study had some limitations that may impact the generalizability of the results. First, the sample was purchased from an online crowdsourcing platform, Prolific. The advantages of crowdsourcing panel providers include the ability to recruit a large number of participants for a relatively low cost. A limitation is that, like most samples recruited from online panels, this study’s sample overrepresented well-educated white adults and is, therefore, not representative of the U.S. adult population. However, comparison studies show that Prolific samples are more representative than alternative platforms and produce higher-quality data [47,48]. Future studies conducted with representative samples would be useful for determining how ethnicity, income, and education levels influence the relationship between clothing style confidence and interest in upcycling. Second, the method was a cross-sectional survey; therefore, causal relationships cannot be derived from the findings. Nevertheless, the study’s findings provide valuable insights into relationships between values, clothing style confidence, and upcycling behaviors that can be tested in experimental designs. For example, future research might explore the effectiveness of various appeals based on clothing style confidence to determine their effect on purchase intentions. There are also opportunities for future research to explore the relationship between personal values, clothing style confidence, and other sustainable clothing behaviors, such as the repair and disposition of clothing. As Park and Lee have noted [66], sustainable consumption encompasses a wide range of behaviors beyond the purchase of sustainable clothing products. Last, this study examined consumers from one country, the United States. Currently, the CSC scale has only been validated with a U.S. sample. Future research could validate the scales’ use in other countries/cultures to determine cross-cultural differences in the influence of values on clothing style confidence and sustainable clothing consumption.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of The University of New Mexico (protocol number 2307073033; date of approval 14 August 2023) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Deidentified data can be obtained from the author upon request.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to extend sincere thanks to anonymous reviewers for providing helpful comments and suggestions on earlier drafts of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Remy, N.; Speelman, E.; Swartz, S. Style That’s Sustainable: A New Fast-Fashion Formula. 20 October 2016. McKinsey & Co. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/sustainability/our-insights/style-thats-sustainable-a-new-fast-fashion-formula (accessed on 6 March 2024).

- A New Textiles Economy: Redesigning Fashion’s Future, 2017. Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Available online: http://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/a-new-textiles-economy (accessed on 6 March 2024).

- Fashion on Climate: How the Fashion Industry Can Urgently Act to Reduce Its Greenhouse Gas Emissions. 26 August 2020. McKinsey & Company & GFA. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/retail/our-insights/fashion-on-climate (accessed on 6 March 2024).

- Reichart, E.; Drew, D. By the Numbers: The Economic, Social and Environmental Impacts of “Fast Fashion”. 10 January 2019. World Resources Institute. Available online: https://www.wri.org/insights/numbers-economic-social-and-environmental-impacts-fast-fashion (accessed on 6 March 2024).

- Ekström, K.M. Consumption of clothes and the problems of waste in affluent societies: Understanding the driving forces of consumption and waste. In Marketing Fashion: Critical Perspectives on the Power of Fashion in Contemporary Culture, 1st ed.; Ekström, K.M., Ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 171–186. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, D. Fashionopolis: Why What We Wear Matters; Penguin: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, X.; Hong, Y.; Zeng, X.; Dai, X.; Wagner, M. A systematic literature review for the recycling and reuse of wasted clothing. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saqib, Z.A.; Qin, L.; Menhas, R.; Lei, G. Strategic sustainability and operational initiatives in small- and medium-sized manufacturers: An empirical analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, K. Clothing upcycling, textile waste and the ethics of the global fashion industry. ZoneModa J. 2019, 9, 173–184. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt, D.; Silverman, J.; Dickson, M.A. Consumer interest in upcycling techniques and purchasing upcycled clothing as an approach to reducing textile waste. Int. J. Fash. Des. Technol. Educ. 2019, 12, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Follett, G. Gen Z Shoppers Prioritize Influencer Recommendations and Sustainability in Clothing Purchases. Ad Age, 14 June 2023. Available online: https://adage.com/article/marketing-news-strategy/gen-z-prioritizes-influencer-recommendations-sustainability-clothing-purchases-study/2499696 (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Manley, A.; Seock, Y.-K.; Shin, J. Exploring the perceptions and motivations of Gen Z and Millennials toward sustainable clothing. Fam. Consum. Sci. Res. J. 2023, 51, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, F.; Roby, H.; Dibb, S. Sustainable clothing: Challenges, barriers and interventions for encouraging more sustainable consumer behaviour. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2016, 40, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrani, M. People gather for stranger things, so why not this? Learning sustainable sensibilities through communal garment-mending practices. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J.; Lin, L.M. Exploring attitude-behavior gap in sustainable consumption: Comparison of recycled and upcycled fashion products. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 623–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyner Armstrong, C.M.; Kang, J.; Lang, C. Clothing style confidence: The development and validation of a multidimensional scale to explore product longevity. J. Consum. Behav. 2018, 17, 553–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bly, S.; Gwozdz, W.; Reisch, L.A. Exit from the high street: An exploratory study of sustainable fashion consumption pioneers. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2015, 39, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, E.; Gupta, S.; Kim, Y.-K. Style consumption: Its drivers and role in sustainable apparel consumption. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2015, 39, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H.; Bilsky, W. Toward a universal psychological structure of human values. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 53, 550–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Zanna, M.P., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992; Volume 25, pp. 1–65. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S.H. Are there universal aspects in the content and structure of values? J. Soc. Issues 1994, 50, 19–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homer, P.M.; Kahle, L.R. A structural equation test of the value-attitude-behavior hierarchy. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 638–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sproles, G.B. The psychology of fashion. In Behavioral Sciences Theories of Fashion; Solomon, M.R., Ed.; Lexington Books: Lexington, MA, USA, 1985; pp. 55–70. [Google Scholar]

- Rokeach, M. The Nature of Human Values; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, R.M., Jr. Change and stability in values and value systems: A sociological perspective. In Understanding Human Values Individual and Societal; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1979; pp. 15–46. [Google Scholar]

- Kluckhohn, C. Values and value orientations in the theory of action: An exploration in definition and classification. In Toward a General Theory of Action; Parsons, T., Shils, E., Eds.; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1951; pp. 388–433. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, L.V. The Measurement of Interpersonal Values; Science Research Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Milfront, T.L.; Duckitt, J.; Wagner, C. A cross-cultural test of the value-attitude-behavior hierarchy. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 40, 2791–2813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundblad, L.; Davies, I.A. The values and motivations behind sustainable fashion consumption. J. Consum. Behav. 2016, 15, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jägel, T.; Keeling, K.; Reppel, A.; Gruber, T. Individual values and motivational complexities in ethical clothing consumption: A means-end approach. J. Mark. Manag. 2012, 28, 373–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, G.P. Appearance and the self. In Dress, Adornment, and the Social Order; Roach, M.E., Eicher, J.B., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1965; pp. 216–245. [Google Scholar]

- Sproles, G.B.; Burns, L.D. Changing Appearances: Understanding Dress in Contemporary Society; Fairchild: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 179–219. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, S.B. The Social Psychology of Clothing: Symbolic Appearances in Context, 2nd ed.; Fairchild: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, L.L.; Miller, F.G. Conformity and judgments of fashionability. Home Econ. Res. J. 1983, 11, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, J.B.; Dixon, M.E.; O’Brien, P.E. Body Image: Appearance orientation and evaluation in the severely obese. Changes with weight loss. Obes. Surg. 2002, 12, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumer, H. Symbolic Interactionism: Perspective and Method; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Niinimäki, K. Eco-clothing, consumer identity and ideology. Sust. Dev. 2010, 18, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, R. Fashion police to fast fashion: “Slow down and pull over!”. In Marketing Fashion: Critical Perspectives on the Power of Fashion in Contemporary Culture, 1st ed.; Ekström, K.M., Ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, M.Z.; Yan, R.-N. An exploratory study of the decision processes of fast versus slow fashion consumers. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2013, 17, 141–159. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, K.S.; Joanes, T.; Webb, D.; Gupta, S.; Gwozdz, W. Exploring the psychological characteristics of style and fashion clothing orientations. J. Consum. Mark. 2023, 40, 897–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Gwozdz, W.; Gentry, J. The role of style versus fashion orientation on sustainable apparel consumption. J. Macromark. 2019, 39, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, K.; Grose, L. Fashion and Sustainability: Design for Change; Laurence King Publishing, Ltd.: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mintel. Men’s Clothing, US—2023. Mintel Market Research Reports Database. Available online: https://portal-mintel-com.libproxy.unm.edu (accessed on 17 April 2024).

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 4th ed.; Allyn & Bacon: Needham Heights, MA, USA, 2001; pp. 56–110. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.-G. Statistical power analyses using G*power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 40, 120–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peer, E.; Brandimarte, L.; Samat, S.; Acquisti, A. Beyond the Turk: Alternative platforms for crowdsourcing behavioral research. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2017, 70, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, B.D.; Ewell, P.J.; Brauer, M. Data quality in online human-subjects research: Comparisons between MTurk, Prolific, CloudResearch, Qualtrics, and SONA. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0279720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Guagnano, G.A. A brief inventory of values. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1998, 58, 984–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H.; Boehnke, K. Evaluating the structure of human values with confirmatory factor analysis. J. Res. Personal. 2004, 38, 230–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.-M. SmartPLS, Version 4; SmartPLS: Oststeinbek, Germany, 2022. Available online: https://www.smartpls.com (accessed on 26 April 2024).

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Howard, M.C.; Nitzl, C. Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 109, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F.; Nitzl, C.; Ringle, C.M.; Howard, M.C. Beyond a tandem analysis of SEM and PROCESS: Use of PLS-SEM for mediation analyses! Int. J. Mark. Res. 2020, 62, 288–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, J.M.; Klein, K.; Wetzels, M. Hierarchical latent variable models in PLS-SEM: Guidelines for using reflective-formative type models. Long Range Plann. 2012, 45, 359–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F.; Cheah, J.-H.; Becker, J.-M.; Ringle, C.M. How to specify, estimate, and validate higher-order constructs in PLS-SEM. Australas. Mark. J. 2019, 27, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Lynch, J.G.; Chen, Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Dias, R.S.; Spiller, S.S.; Fitzsimmons, G.J. Understanding effect sizes in consumer psychology. Mark. Lett. 2023, 34, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Mod. Methods Bus. Res. 1998, 295, 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Dao, J.F.; Joyner Martinez, C.M. Defining sustainable clothing use: A taxonomy for future research. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2024, 48, e13033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, K.A.; Weaver, S.T. The intersection of sustainable consumption and anticonsumption: Repurposing to extend product life spans. J. Public Policy Mark. 2018, 37, 291–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEachern, M.G.; Middleton, D.; Cassidy, T. Encouraging sustainable behaviour change via a social practice approach: A focus on apparel consumption practices. J. Consum. Policy 2020, 43, 397–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Lee, Y. Scale development of sustainable consumption of clothing products. Sustainability 2021, 13, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).