Abstract

Organizations committed to sustainability and reducing their environmental footprint depend largely on the pro-environmental performance of their employees. This study investigates how environmentally specific transformational leadership (ESTL) shapes employee pro-environmental performance, as well as the mediating role of employee environmental awareness and the boundary condition of emotional exhaustion at work. Data were collected from 264 participants across three waves. The findings reveal that ESTL exerts a positive influence on employee environmental awareness, which in turn enhances pro-environmental performance. Additionally, the positive indirect effect of ESTL on pro-environmental performance through environmental awareness is moderated by emotional exhaustion, being stronger when the emotional exhaustion level is low. These findings highlight the critical role of leadership in fostering environmental sustainability within organizations and the importance of considering employee psychological well-being in the process. Our research contributes to the understanding of how specific leadership behaviors can drive pro-environmental actions in the workplace, offering practical implications for organizational leaders aiming to enhance environmental performance.

1. Introduction

“For sustainable development to be achieved, it is crucial to harmonize three core elements: economic growth, social inclusion and environmental protection.”—The United Nations

In an era where environmental sustainability is a pressing concern, organizations are increasingly recognizing the importance of fostering pro-environmental behaviors among their employees [1]. Employee pro-environmental performance, which encompasses actions that contribute to environmental sustainability at the workplace, is critical for organizations aiming to reduce their environmental footprint and achieve long-term sustainability goals [2,3]. Promoting such behaviors not only enhances environmental performance but also aligns organizational practices with employees’ values, fostering greater engagement, satisfaction, and a shared commitment to sustainability.

Adopting the conservation of resources (COR) theory [4,5] as a conceptual framework, this research investigates the role of environmentally specific transformational leadership (ESTL) in enhancing employee pro-environmental performance. It explores the mechanisms through which ESTL exerts its influence, specifically focusing on the mediating effect of employee environmental awareness. Additionally, this research examines the impact of employee psychological resources on this process, providing a comprehensive understanding of how leadership can effectively promote sustainable practices within organizations.

Transformational leadership, a concept first introduced by Burns [6] and further developed by Bass [7], emphasizes the leader’s role in inspiring and motivating followers to achieve extraordinary outcomes. This leadership style is characterized by four key components: idealized influence, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration. Idealized influence involves leaders acting as ethical role models, fostering trust and respect from their followers [8]. Inspirational motivation entails the articulation of a compelling vision that provides a sense of purpose and drives collective efforts toward organizational goals. Intellectual stimulation encourages followers to challenge existing assumptions and embrace innovative approaches, thereby fostering a culture of creativity and problem solving [9]. These components collectively enable transformational leaders to elevate their followers’ performance and commitment to the organization [10].

Building on these premises, Roberson and Barling conceptualized ESTL as “a manifestation of transformational leadership in which the content of the leadership behaviors are all focused on encouraging pro-environmental initiatives” [11] (p. 177). Leaders who embody environmentally specific transformational leadership will motivate their subordinates to engage in pro-environmental behaviors at work. They tend to serve as role-models and commit morally to environmental sustainability. Furthermore, by exhibiting inspirational motivation, these leaders use their passion and optimism to encourage employees to engage in environmentally friendly behaviors that benefit the collective good. Practicing intellectual stimulation, they prompt employees to view environmental issues from new perspectives, question current practices, and devise innovative solutions. Lastly, leaders demonstrating individualized consideration build strong relationships with followers, communicate their environmental values, model sustainable behaviors, and encourage reevaluation of environmental priorities [12].

COR theory posits that individuals are driven to protect their existing resources and acquire new ones, which is vital for coping with stress and achieving goals. Resources can be tangible (e.g., time, money) or intangible (e.g., social support, self-efficacy) [13]. According to this theory, ESTL can be perceived as a significant resource gain for employees. First, transformational leaders offer emotional support and motivation, which can enhance employees’ psychological well-being and resilience. This emotional support helps employees feel valued and understood, reducing feelings of burnout and emotional exhaustion, which are forms of resource loss [14]. Second, ESTL provides clear vision and guidance, increasing employees’ self-efficacy and confidence in their ability to engage in pro-environmental behaviors. By articulating a compelling environmental vision and leading by example, transformational leaders foster an environment where employees are more likely to internalize and prioritize environmental values. This, in turn, encourages proactive behaviors aimed at environmental sustainability. Therefore, through emotional support, motivation, and guidance, ESTL not only equips employees with new resources but also helps them conserve their existing resources by mitigating stress and enhancing their capacity for sustained engagement in pro-environmental initiatives. Leaders who exemplify and promote environmental values are not only likely to enhance the employees’ environmental awareness, but also inspire them to take initiative by engaging in environmental protection activities within the organization [15].

ESTL enhances employee pro-environmental performance by increasing employees’ environmental awareness, which serves as a cognitive resource that motivates and informs their actions toward sustainability. This awareness acts as a crucial step, translating the leader’s influence into concrete environmental behaviors. Conversely, emotional exhaustion represents a resource loss [16], depleting the energy and emotional reserves that employees might otherwise invest in pro-environmental activities. Emotional exhaustion, a key component of burnout, is characterized by feelings of being emotionally drained and fatigued, which can undermine an employee’s capacity to engage in discretionary behaviors, including those that benefit the environment [17]. This study hypothesizes that the positive effects of ESTL on employee pro-environmental performance are mediated by increased environmental awareness and moderated by levels of emotional exhaustion.

The findings of this research add to the growing body of literature on environmental leadership and employee sustainability behaviors by elucidating the dual role of ESTL as both a resource gain and a mitigating factor against resource loss [18]. Additionally, this study underscores the importance of considering employee well-being, specifically emotional exhaustion, in fostering a sustainable organizational culture. The practical implications of these findings suggest that organizational leaders should not only adopt environmentally specific transformational leadership practices but also be vigilant in addressing factors that contribute to employee burnout, to optimize pro-environmental performance within organizations.

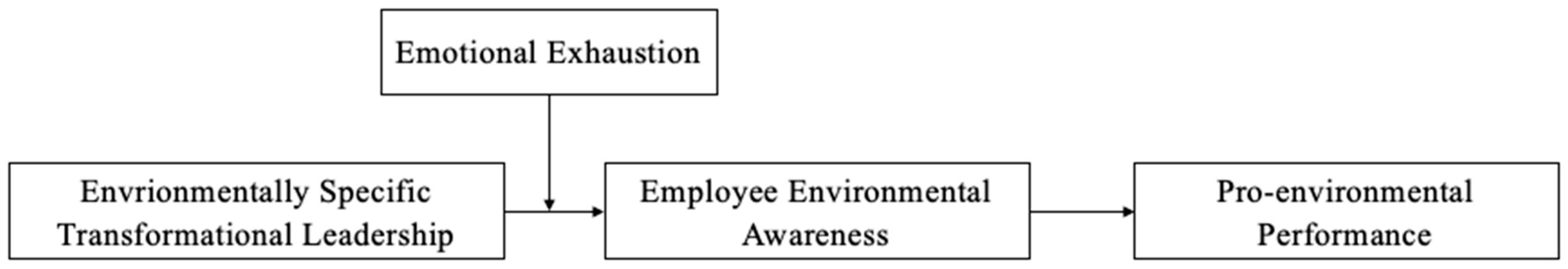

Our research makes three key contributions. First, we propose a model that highlights the critical role of leadership in informing employee environmental performance, demonstrating that ESTL significantly motivates employees to engage in pro-environmental behaviors at work. Second, it identifies environmental awareness as a crucial mechanism through which ESTL influences employee behaviors, signaling the importance of leadership in fostering environmental consciousness among employees. Third, we underscore the role of emotional exhaustion as a moderator. Specifically, we highlight how employee emotional exhaustion moderates the relationship between ESTL and employee environmental awareness. This emphasizes the significance of employee psychological resources in shaping the impact of leadership on environmental awareness and employee pro-environmental performance (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The hypothesized model.

2. Theory and Hypotheses

Environmentally Specific Transformational Leadership and Environmental Awareness

Over the years, research on transformational leadership research has consistently demonstrated that this particular leadership approach is associated with positive outcomes, including increased follower satisfaction, higher levels of performance, and greater organizational commitment [19,20,21]. Owing to its effectiveness in motivating employees, Robertson and Barling introduced the concept of ESTL, to highlight its role in environmental protection, which refers to “a manifestation of transformational leadership in which the content of the leadership behaviors is all focused on encouraging pro-environmental initiatives” [11] (p. 177). Extensive evidence indicates that ESTL enhances employee environmental protection behaviors at work beyond the impact of general leadership styles [22,23,24,25]. Boeske reviewed the environmental leadership literature and outlined several significant benefits associated with such a leadership style [26]. Althnayan et al. also found that ESTL positively predicts organizational sustainable performance [27]. In a similar vein, empirical evidence suggests that ESTL and green HRM have a synergistic effect on employee environmental protection behavior [15].

When leaders specifically focus on environmental issues, they can cultivate a culture of environmental consciousness within the organization. These leaders typically emphasize the importance of environmental sustainability, educate employees on environmental issues, and exemplify sustainable practices [28]. This approach can enhance employees’ awareness and knowledge about environmental issues, as employees are more inclined to embrace the values and priorities demonstrated by their leaders [12]. ESTL is likely to result in heightened levels of environmental awareness among employees [29], as leaders act as role models and provide a clear vision for environmental responsibility. Thus, we propose that:

Hypothesis 1.

Environmentally specific transformational leadership is positively related to employee environmental awareness.

Transformational leaders not only increase awareness but also inspire action [21,30]. Studies have shown that transformational leadership is linked to higher levels of employee motivation and engagement, which translates into more proactive and sustained environmental behaviors in the workplace, under the influence of the employees’ leaders [31]. By providing education and resources on environmental issues, leaders equip employees with the necessary knowledge and skills to perform their tasks in an environmentally sustainable manner. Empirical examinations have identified links between green leadership and follower characteristics that relate to environmental concerns, such as commitment to environmental initiatives [32] and employee green advocacy [33].

By emphasizing the significance of environmental sustainability and integrating it into the organizational mission, these leaders can motivate employees to engage in pro-environmental behaviors [34], which include actions such as reducing waste, conserving energy, or supporting sustainable practices [35]. Environmentally specific transformational leaders not only provide the resources and support necessary for employees to engage in these behaviors, but also reinforce these behaviors by rewarding and recognizing pro-environmental actions [36]. This encouragement and reinforcement can lead to increased employee engagement in pro-environmental performance. Thus, we posit that:

Hypothesis 2.

Environmentally specific transformational leadership is positively related to employee pro-environmental performance.

We propose that the relationship between environmentally specific transformational leadership and employee pro-environmental performance is mediated by environmental awareness. When leaders prioritize environmental issues, they increase employees’ knowledge and understanding of these issues, which in turn influences their behaviors [37]. Employees who are more aware of environmental problems and solutions are more likely to engage in actions that support environmental sustainability [38]. This increased awareness serves as a crucial intermediary step, translating the leaders’ environmental focus into concrete pro-environmental actions by employees. Several studies support the idea that awareness is a critical precursor to behavior change [39,40], indicating that increasing environmental awareness is a key mechanism for transformational leaders to enhance employees’ pro-environmental performance. Unlike other leadership styles, ESTL uniquely integrates an environmental focus within the transformational leadership framework, emphasizing the importance of environmental values and sustainability. While other leadership styles can increase awareness, ESTL combines this with motivational elements, inspirational vision, and individualized support that are particularly effective in fostering deep environmental commitment and translating awareness into sustained pro-environmental actions.

Hypothesis 3.

Environmentally specific transformational leadership has a positive indirect effect through employee environmental awareness on employee pro-environmental performance.

In line with COR theory, when employees are in a resource-loss state, they are less motivated and are likely to withdraw from work [41]. Emotional exhaustion is such a state in which employees feel emotionally drained and depleted of emotional resources, which can significantly impact their ability to respond to leadership [42]. Therefore, it is reasonable to postulate that when employees are emotionally exhausted, they are less likely to be receptive to the influence of transformational leadership because their capacity to process new information and engage in additional activities is compromised. In the context of environmentally specific transformational leadership, emotionally exhausted employees may not fully absorb or prioritize the environmental messages and initiatives promoted by their leaders [43]. Consequently, the positive impact of ESTL on environmental awareness is likely diminished. Conversely, when emotional exhaustion level is low, employees have more emotional and cognitive resources available to engage with and respond positively to their leaders’ environmental initiatives, leading to higher levels of environmental awareness. Thus, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 4.

Employee emotional exhaustion moderates the relationship between environmentally specific transformational leadership and environmental awareness, such that when the emotional exhaustion level is high, this relationship will be weaker than when the emotional exhaustion level is low.

Further, we posit that the effectiveness of environmentally specific transformational leadership in enhancing pro-environmental performance via environmental awareness is influenced by the emotional state of employees, specifically their level of emotional exhaustion. When emotional exhaustion levels are low, employees have greater emotional and cognitive resources to absorb and act upon the environmental awareness promoted by leaders who adopt ESTL [44]. In this state, employees are more capable of internalizing the environmental values and knowledge imparted by their leaders, which translates into higher pro-environmental performance. Essentially, they are more receptive to the influence of ESTL and can better align their behaviors with the environmental goals set by their leaders. Conversely, when emotional exhaustion levels are high, employees are less likely to effectively process the environmental information and inspiration provided by their leaders. The cognitive and emotional toll of exhaustion means that employees may struggle to prioritize or engage with environmental initiatives, even if they are aware of their importance [45]. This diminishes the indirect effect of ESTL on pro-environmental performance through environmental awareness because the link between awareness and action is weakened by the employees’ reduced capacity to act on their knowledge and values. In other words, when employees are not emotionally exhausted, they are better able to leverage their environmental awareness into concrete pro-environmental actions, enhancing the positive impact of ESTL. Conversely, high levels of emotional exhaustion impede this process, weakening the overall effect. We therefore hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 5.

The positive indirect effect of environmentally specific transformational leadership through environmental awareness on pro-environmental performance will be stronger (weaker) when employee emotional exhaustion level is low (high).

3. Method

3.1. Participants and Procedure

A total of 350 employees at a real estate company were invited to participate in this study. Participants were introduced to the purpose of this study and ensured anonymity in their participation. Questionnaires were distributed three times with a one-month time interval between each wave. At time 1, we surveyed demographic information and emotional exhaustion, as well as environmentally specific transformational leadership, and received 322 responses. At time 2, we asked participants to fill out questionnaires on environmental awareness and received 298 responses. At time 3, we measured pro-environmental performance, and the final sample consisted of 264 employees (response rate 75.4%). Among the participants, 28.6% were male, and 71.4% were female. The majority of participants were aged 30–40 (49.8%), with 34.1% of the participants aged between 40 and 50. On average, participants had worked for 7.08 years (SD = 5.48).

3.2. Measures

All variables in this study were measured using well-established and widely used existing measures (see Appendix A). Surveys were translated into Chinese following Brislin’s translation–back translation procedure [46]. All items were measured using a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree).

Environmentally specific transformational leadership. Environmentally specific transformational leadership was measured using the abbreviated ETFL scale developed by Robertson [12], which contained 4 items. One sample item is “My leader acts as an environmental role model”. Cronbach’s α for this scale was 0.946.

Environmental awareness. The environmental awareness scale was measured using a four-item scale developed by Ryan and Spash and that was adopted by Han and Yoon [29,47]. One sample item is “Environmental protection will provide a better world for me and my children”. Cronbach’s α for this scale was 0.952.

Pro-environmental performance. We measured employee pro-environmental performance at work using three items developed by Bissing-Olson et al. [48]. One sample item is “I take the chance to get actively involved in environmental protection at work”. Cronbach’s α for this scale was 0.892.

Emotional exhaustion. A short form of emotional exhaustion comprising three items was adopted from the subscale of the abbreviated Maslach Burnout Inventory (aMBI) [49]. One sample item is “I feel emotionally drained from my work”. This version was widely adopted and validated [50]. Cronbach’s α for this scale was 0.863.

Control variables. Previous research has demonstrated that these demographic variables affect our focal variables [51,52,53]. Therefore, we controlled for participants’ age, tenure, and gender.

3.3. Analytical Strategy

Data analysis was conducted in Mplus and Process macro in the SPSS version 27 software [54,55]. Confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to examine the discriminant validity of latent variables. Confidence intervals were calculated using bootstrap sampling with 5000 samples to test the significance level of indirect effects.

4. Results

4.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

The results of the confirmatory factor analysis are shown in Table 1. The four-factor measurement model demonstrated a good fit for the data ( = 180.99, SRMR = 0.05, RMSEA = 0.08, CFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.96). It fits the data significantly better than alternative models, i.e., a three-factor model, a two-factor model, and a one-factor model with all items loading on one factor.

Table 1.

Confirmatory factor analysis.

4.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

The means, standard deviations, and correlation figures of the variables are shown in Table 2. As shown in Table 2, ESTL is negatively correlated with emotional exhaustion (r = −0.21, p < 0.01) and positively correlated with environmental performance (r = 0.60, p < 0.01). The initial results validated our hypotheses.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and intercorrelations.

4.3. Hypothesis Tests

Hypothesis 1 proposed a positive relationship between environmentally specific transformational leadership and employee environmental awareness. The path analysis results suggest that environmentally specific transformational leadership was significantly and positively related to employee environmental awareness (β = 0.97, SE = 0.13, p < 0.001), thus supporting Hypothesis 1.

Hypothesis 2 suggested a positive relationship between environmentally specific transformational leadership and employee pro-environmental performance. The results suggest that (β = 0.13, SE = 0.05, p < 0.05), supporting Hypothesis 2.

Hypothesis 3 indicated an indirect effect between environmentally specific transformational leadership and employee pro-environmental performance through employee environmental awareness. To examine the proposed indirect effect, we employed a bootstrapping sampling method with 5000 replications and obtained the 95% bias-corrected confidence interval. The results revealed a significant indirect effect (indirect effect = 3.68; boot SE = 0.54; 95%CI [0.26, 0.48]), therefore supporting Hypothesis 3.

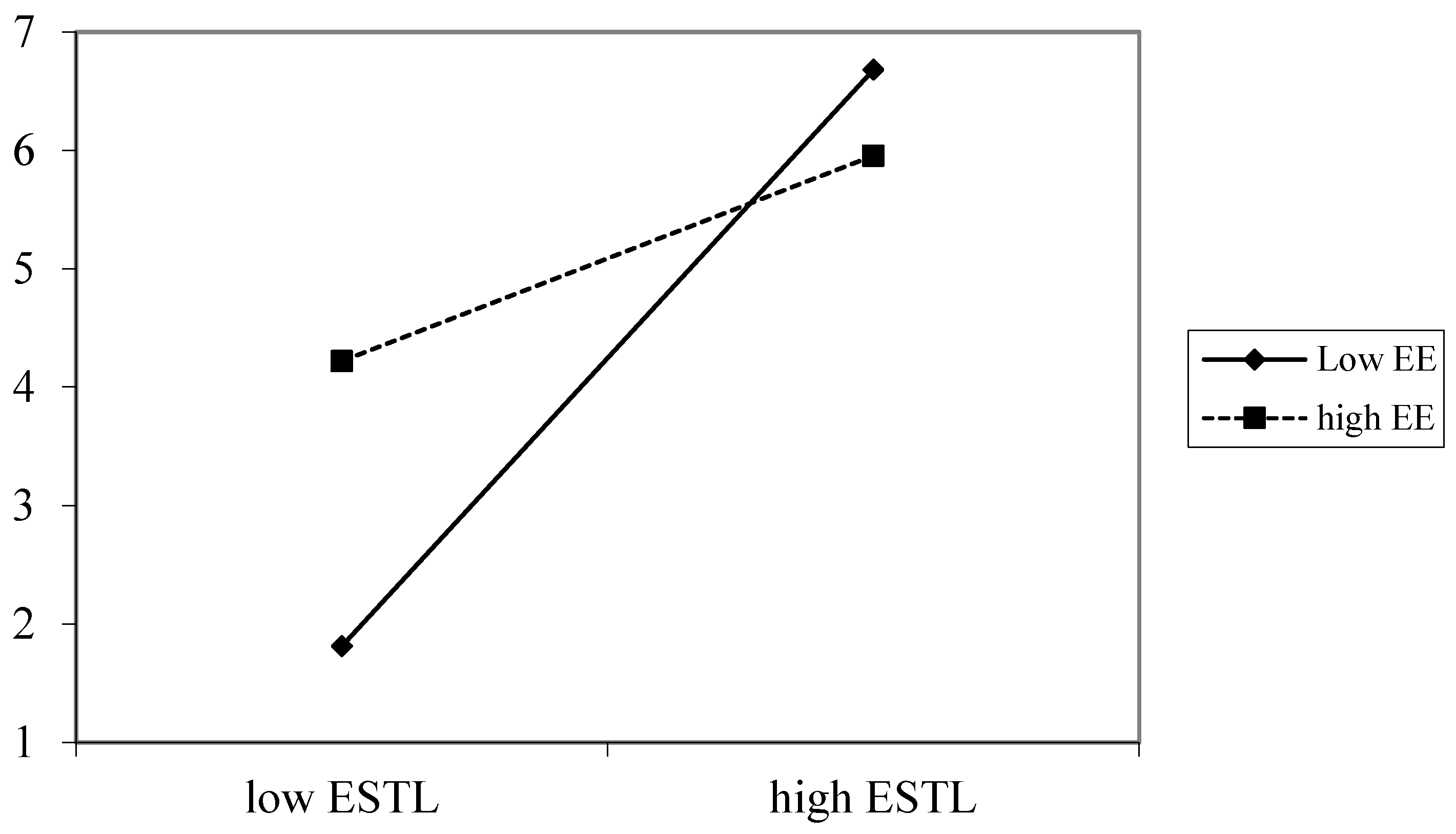

Next, we examined whether employee emotional exhaustion moderated the relationship between environmentally specific transformational leadership and employee environmental awareness, such that when the emotional exhaustion level is high, this relationship is weaker (i.e., Hypothesis 4). The results suggest a significant negative effect (β = −0.09, SE = 0.03, p < 0.01). We plotted the interaction effect to aid further interpretation (Figure 2). As expected, the results of simple slope tests suggest that environmentally specific transformational leadership was less positively related to employee environmental awareness when emotional exhaustion was higher (β = 0.49, boot SE = 0.05; 95%CI [0.39, 0.60], with moderator 1 SD above the mean) than when emotional exhaustion was lower (β = 0.77, boot SE = 0.07; 95%CI [0.62, 0.91], with moderator 1 SD below the mean). Hypothesis 4 was supported.

Figure 2.

The interaction between environmental specific transformational leadership and employee emotional exhaustion on employee environmental awareness. Note. ESTL = environmentally specific transformational leadership; EE = emotional exhaustion.

We then tested the full moderated mediation model in which the indirect effect between environmentally specific transformational leadership and employee pro-environmental performance via employee environmental awareness depends on the level of emotional exhaustion. Following Edwards and Lambert [56], we used a bootstrapping sampling method and obtained bias-corrected confidence intervals at different values of emotional exhaustion. Consistent with our assumptions, the results revealed a significant moderated mediation effect (β = −0.06, boot SE = 0.04; 95%CI [−0.141, −0.003]), such that when the emotional exhaustion level was high, the indirect effect was weaker (β = 0.32, boot SE = 0.06; 95%CI [0.19, 0.43]) compared with when the emotional exhaustion level was low (β = 0.49, boot SE = 0.10; 95%CI [0.32, 0.71]), supporting Hypothesis 5.

5. Discussion

The findings provide support for the proposed model, highlighting the critical role of environmentally specific transformational leadership in fostering environmental awareness and promoting pro-environmental performance among employees. Our data suggest that such leadership significantly increases environmental awareness and promotes pro-environmental behaviors. Moreover, the study reveals that environmental awareness mediates the relationship between ESTL and employee pro-environmental performance, emphasizing its importance as an intermediary. Additionally, our findings supported emotional exhaustion as a moderator that weakens the positive impact of ESTL on environmental awareness when the employee emotional exhaustion level is high, and reduces the indirect effect on performance through awareness under the same conditions. These findings highlight the necessity for organizations to not only foster environmentally focused leadership but also to address employee well-being to fully realize the benefits of ESTL.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

This study makes several important theoretical contributions to the fields of leadership as well as environmental sustainability. First, it extends the transformational leadership theory by integrating an environmental perspective, demonstrating that environmentally specific transformational leadership can significantly and positively influence employee attitudes and behaviors toward sustainability. This nuanced understanding enriches the existing leadership literature by adding to the specific domain of environmental responsibility. Previous research on transformational leadership has primarily focused on general employee outcomes such as job satisfaction, performance, and organizational commitment [57]. By incorporating an environmental dimension, our study highlights the importance of leadership in addressing global sustainability challenges and underscores the role of leaders in shaping environmentally responsible organizational practices [58].

Second, previous studies have suggested that transformational leaders enhance employee awareness of organizational goals and values [59], but our research specifically demonstrates how this awareness translates into pro-environmental actions. Our findings underscore the critical role of environmental awareness as a mediator in the relationship between transformational leadership and pro-environmental performance. This extends the line of inquiry on the mechanisms through which leadership influences employee behavior, providing empirical evidence that awareness is a crucial precursor to action in the context of environmental sustainability.

Third, by identifying emotional exhaustion as a moderator, this study offers a more comprehensive model of the factors that affect the efficacy of transformational leadership. Previous research has highlighted the critical role of ESTL on environmental outcomes but lacks examination of boundary conditions [30]. This finding highlights the importance of employee well-being in leadership effectiveness, particularly in promoting pro-environmental behavior. This theoretical insight integrates concepts from occupational health psychology into the leadership and sustainability discourse, suggesting that the emotional and psychological states of employees can significantly impact the outcomes of leadership interventions.

Finally, this research contributes to the growing literature on pro-environmental behavior in organizations. It provides empirical evidence that leadership can be a powerful tool for fostering sustainability, offering a clear pathway through which organizational leaders can influence and enhance employee environmental performance. Previous studies have shown that leadership can shape organizational culture and influence employee behaviors [60]. Our findings specifically demonstrate the potential of ESTL to drive pro-environmental behavior, thereby bridging transformational leadership theory and environmental management. This study informs future research at the intersection of these fields and suggests practical strategies for leaders aiming to promote sustainability within their organizations [61].

5.2. Practical Implications

Our findings suggest that organizations should invest in developing environmentally specific transformational leadership. Training programs and leadership development initiatives should include a strong focus on environmental issues, equipping leaders with the skills and knowledge to promote sustainability within their teams. Efficient resource use, waste reduction, and energy conservation not only benefit the environment but also enhance the economic performance of businesses by lowering operational costs and fostering innovation in sustainable practices.

Second, the mediating role of environmental awareness indicates that leaders should actively work to increase employees’ understanding of environmental issues. This can be achieved through regular communication, educational workshops, and by setting an example through their own environmentally responsible behaviors [62]. By fostering a culture of environmental awareness, leaders can drive more substantial and sustained pro-environmental actions among employees.

Moreover, addressing employee emotional exhaustion is crucial. Organizations should implement policies and practices that support employee well-being, such as stress management programs, flexible work arrangements, and providing sufficient resources and support. By reducing emotional exhaustion, organizations can enhance the positive effects of transformational leadership on pro-environmental performance.

Lastly, these findings encourage organizations to create an integrated strategy that combines leadership development, employee education, and well-being support to achieve their environmental sustainability goals. This holistic approach ensures that employees are not only aware of environmental issues but are also motivated and capable of engaging in pro-environmental behaviors.

6. Conclusions

This study provides compelling evidence that environmentally specific transformational leadership significantly enhances both environmental awareness and pro-environmental performance among employees. By demonstrating the mediating role of environmental awareness and the moderating effect of emotional exhaustion, our findings offer a nuanced understanding of how and when transformational leadership can be most effective in promoting environmental sustainability within organizations. The results of our study also highlight that organizations seeking to improve their environmental performance should cultivate transformational leadership that specifically focuses on environmental issues. Additionally, addressing employee emotional exhaustion is crucial to ensure that the positive effects of such leadership are fully realized. By fostering a supportive work environment and prioritizing employee well-being, organizations can enhance their employees’ capacity to engage in pro-environmental behaviors, thereby achieving greater overall sustainability.

Our study is not without limitations. Though the study was conducted using a multi-wave design to avoid common-method variance, the results cannot infer causal relationships. Future research could consider adopting longitudinal or experimental designs to examine the causal relationships. Furthermore, in considering the role of employee psychological state in the process, emotional exhaustion could also be acting as a factor that explains why environmentally aware individuals fail to exhibit pro-environmental behaviors [63]. Future studies are also encouraged to consider additional moderating factors, such as team factors or organizational climate, and consider different organizational contexts. This will further our understanding of how to effectively promote environmental sustainability through leadership and organizational practices. Also, the measurement of leadership style is based on employee perceptions, which may not accurately reflect the actual practices of the leaders. While perceptions are critical as they influence employee behaviors and attitudes, they may not fully capture the true extent of ESTL being practiced. Future research could benefit from incorporating multi-source data, including self-reports from leaders and objective measures of leadership behaviors, to provide a more comprehensive understanding of ESTL’s impact.

Author Contributions

Q.R.: conceptualization, investigation, methodology, funding acquisition, writing—original draft. W.L.: methodology, data curation, formal analysis. C.M.: writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Fundamental Research Funds for the Central University. Funding number: JBK23YJ69.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The data were collected by the author whose affiliated university in China does not have an Institutional Review Board (IRB). The author ensured that the data collection procedure strictly followed the requirements as declared in the Nuremberg Code, the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki, and other international conventions on human rights. The analyses of this study were based on anonymized data.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Measurement Scales Used in the Study

Environmentally specific transformational leadership:

My leader acts as an environmental role model.

My leader takes note of my individual contributions to the organization’s environmental performance.

My leader is passionate about improving the future state of the natural environment.

My leader urges me to think creatively about improving our organization’s environmental performance.

Environmental awareness:

The effects of pollution on public health are worse than we realize.

Over the next several decades, thousands of species will become extinct.

Claims that current levels of pollution are changing earth’s climate are exaggerated.

Emotional exhaustion:

I feel emotionally drained from my work.

I feel fatigued when I get up in the morning and have to face another day on the job.

Working with people all day is really a strain for me.

Pro-environmental performance:

I took a chance to get actively involved in environmental protection at work.

I took initiative to act in environmentally-friendly ways at work.

I did more for the environment at work than I was expected to.

References

- Shaukat, H.S.; Ong, T.S.; Cheok, M.Y.; Bashir, S.; Zafar, H. The impact of green human resource management on employee empowerment and pro-environmental behaviour in Pakistan’s manufacturing industry. J. Environ. Asses. Policy Manag. 2023, 25, 2350015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, J.; Shen, J.; Deng, X. Effects of green HRM practices on employee workplace green behavior: The role of psychological green climate and employee green values. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 56, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampene, A.K.; Li, C.; Wiredu, J.; Agyeman, F.O.; Brenya, R. Examining the nexus between social cognition, biospheric values, moral norms, corporate environmental responsibility and pro-environmental behaviour. Does environmental knowledge matter? Curr. Psychol. 2023, 43, 6549–6569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources theory: Its implication for stress, health, and resilience. In The Oxford Handbook of Stress, Health, and Coping; Folkman, S., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011; p. 147. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, J.M. Leadership; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B.M. Leadership and Performance beyond Expectations; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Nassif, A.G.; Hackett, R.D.; Wang, G. Ethical, virtuous, and charismatic leadership: An examination of differential relationships with follower and leader outcomes. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 172, 581–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanat-Maymon, Y.; Elimelech, M.; Roth, G. Work motivations as antecedents and outcomes of leadership: Integrating self-determination theory and the full range leadership theory. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2020, 38, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Hetland, J.; Olsen, O.K.; Espevik, R. Daily transformational leadership: A source of inspiration for follower performance? Eur. Manag. Rev. 2023, 41, 700–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.L.; Barling, J. Greening organizations through leaders’ influence on employees’ pro-environmental behaviors. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, 176–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.L. The nature, measurement and nomological network of environmentally specific transformational leadership. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 151, 961–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbesleben, J.R.; Neveu, J.-P.; Paustian-Underdahl, S.C.; Westman, M. Getting to the “COR” understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. J. Manag. 2014, 40, 1334–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, M.; Schümann, M.; Vincent-Höper, S. A conservation of resources view of the relationship between transformational leadership and emotional exhaustion: The role of extra effort and psychological detachment. Work Stress 2021, 35, 241–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zuo, W. Arousing employee pro-environmental behavior: A synergy effect of environmentally specific transformational leadership and green human resource management. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2023, 62, 159–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirom, A. Burnout in work organizations. In International Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Cooper, C.L., Robertson, I., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1986; pp. 25–48. [Google Scholar]

- Pu, B.; Sang, W.; Ji, S.; Hu, J.; Phau, I. The effect of customer incivility on employees’ turnover intention in hospitality industry: A chain mediating effect of emotional exhaustion and job satisfaction. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2024, 118, 103665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raineri, N.; Paillé, P. Linking corporate policy and supervisory support with environmental citizenship behaviors: The role of employee environmental beliefs and commitment. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 137, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Piccolo, R.F. Transformational and transactional leadership: A meta-analytic test of their relative validity. J. Appl. Psychol. 2004, 89, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banks, G.C.; McCauley, K.D.; Gardner, W.L.; Guler, C.E. A meta-analytic review of authentic and transformational leadership: A test for redundancy. Leader Q. 2016, 27, 634–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaubroeck, J.; Lam, S.S.; Cha, S.E. Embracing transformational leadership: Team values and the impact of leader behavior on team performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nduneseokwu, C.K.; Harder, M.K. Developing environmental transformational leadership with training: Leaders and subordinates environmental behaviour outcomes. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 403, 136790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kura, K.M. Linking environmentally specific transformational leadership and environmental concern to green behaviour at work. Global. Bus. Rev. 2016, 17, 1S–14S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Chen, X.; Zou, Y.; Nie, Q. Environmentally specific transformational leadership and team pro-environmental behaviors: The roles of pro-environmental goal clarity, pro-environmental harmonious passion, and power distance. Hum. Relat. 2021, 74, 1864–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.L.; Barling, J. Contrasting the nature and effects of environmentally specific and general transformational leadership. Leader Organ. Dev. J. 2017, 38, 22–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeske, J. Leadership towards sustainability: A review of sustainable, sustainability, and environmental leadership. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althnayan, S.; Alarifi, A.; Bajaba, S.; Alsabban, A. Linking Environmental Transformational Leadership, Environmental Organizational Citizenship Behavior, and Organizational Sustainability Performance: A Moderated Mediation Model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.L.; Carleton, E. Uncovering how and when environmental leadership affects employees’ voluntary pro-environmental behavior. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2018, 25, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Yoon, H.J. Hotel customers’ environmentally responsible behavioral intention: Impact of key constructs on decision in green consumerism. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 45, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, H.A.; Vandenberg, R.J. Integrating managerial perceptions and transformational leadership into a work-unit level model of employee involvement. J. Organ. Behav. 2005, 26, 561–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helm, S. Employees’ awareness of their impact on corporate reputation. J. Bus. Res. 2011, 64, 657–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillé, P.; Mejía Morelos, J.H.; Raineri, N.; Stinglhamber, F. The influence of the immediate manager on the avoidance of non-green behaviors in the workplace: A three-wave moderated-mediation model. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 155, 723–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crucke, S.; Servaes, M.; Kluijtmans, T.; Mertens, S.; Schollaert, E. Linking environmentally-specific transformational leadership and employees’ green advocacy: The influence of leadership integrity. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 406–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.; Robertson, J.L. How and when does perceived CSR affect employees’ engagement in voluntary pro-environmental behavior? J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 155, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ren, X. Analysis of the mediating role of psychological empowerment between perceived leader trust and employee work performance. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Guo, Z.; Deng, B.; Wang, B. Unlocking the relationship between environmentally specific transformational leadership and employees’ green behaviour: A cultural self-representation perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 382, 134857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darvishmotevali, M.; Altinay, L. Green HRM, environmental awareness and green behaviors: The moderating role of servant leadership. Tour. Manag. 2022, 88, 104401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hwang, J.; Lee, S. Cognitive, affective, normative, and moral triggers of sustainable intentions among convention-goers. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 51, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoako, G.K.; Dzogbenuku, R.K.; Abubakari, A. Do green knowledge and attitude influence the youth’s green purchasing? Theory of planned behavior. Int. J. Product. Perform. 2020, 69, 1609–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimlich, J.E.; Ardoin, N.M. Understanding behavior to understand behavior change: A literature review. Environ. Educ. Res. 2008, 14, 215–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, T.A.; Cropanzano, R. Emotional exhaustion as a predictor of job performance and voluntary turnover. J. Appl. Psychol. 1998, 83, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordes, C.L.; Dougherty, T.W. A review and an integration of research on job burnout. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1993, 18, 621–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costin, A.; Alina, R.; Balica, R.-Ș. Remote work burnout, professional job stress, and employee emotional exhaustion during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1193854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, G.S.; Irudayasamy, F.G.; Parayitam, S. Emotional exhaustion, emotional intelligence and task performance of employees in educational institutions during COVID 19 global pandemic: A moderated-mediation model. Pers. Rev. 2023, 52, 539–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, J.K.; Brotheridge, C.M. Resources, coping strategies, and emotional exhaustion: A conservation of resources perspective. J. Vocat. Behav. 2003, 63, 490–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. The wording and translation of research instruments. In Field Methods in Cross-Cultural Research; Lonner, W.J., Berry, J.W., Eds.; Sage Publications: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1986; pp. 137–164. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, A.M.; Spash, C.L. Measuring “Awareness of Environmental Consequences”: Two Scales and Two Interpretations; CSIRO Sustainable Ecosystems: Canberra, Australia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bissing-Olson, M.J.; Iyer, A.; Fielding, K.S.; Zacher, H. Relationships between daily affect and pro-environmental behavior at work: The moderating role of pro-environmental attitude. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, 156–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E.; Leiter, M.P. Maslach Burnout Inventory, 3rd ed.; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Riley, M.R.; Mohr, D.C.; Waddimba, A.C. The reliability and validity of three-item screening measures for burnout: Evidence from group-employed health care practitioners in upstate New York. Stress Health 2018, 34, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kearney, E. Age differences between leader and followers as a moderator of the relationship between transformational leadership and team performance. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2008, 81, 803–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ausat, A.; Suherlan, S.; Peirisal, T.; Hirawan, Z. The Effect of Transformational Leadership on Organizational Commitment and Work Performance. J. Leadersh. Organ. 2022, 4, 61–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lajoie, D.; Boudrias, J.-S.; Rousseau, V.; Brunelle, É. Value congruence and tenure as moderators of transformational leadership effects. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2017, 38, 254–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, B.; Muthén, L. Mplus. In Handbook of Item Response Theory; Linden, W.J.v.d., Ed.; Chapman and Hall/CRC: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 507–518. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, J.R.; Lambert, L.S. Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychol. Methods 2007, 12, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguon, V. Effect of Transformational Leadership on Job Satisfaction, Innovative Behavior, and Work Performance: A Conceptual Review. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2022, 17, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Ahmad, S.; Ahmed, I. Linking environment specific servant leadership with organizational environmental citizenship behavior: The roles of CSR and attachment anxiety. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2023, 17, 855–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, L.; Gan, X.; Xu, T.; Long, R.; Qiao, L.; Zhu, H. A new perspective to promote organizational citizenship behaviour for the environment: The role of transformational leadership. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 239, 118002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almerri, H.S.H. Investigating The Impact of Organizational Culture on Employee Retention: Moderating Role of Employee Engagement. J. Syst. Manag. Sci. 2023, 13, 488–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, T.A.; Zacher, H.; Ashkanasy, N.M. Organisational sustainability policies and employee green behaviour: The mediating role of work climate perceptions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, M.M.S.; Hills, P.; Hau, B.C.H. Engaging employees in sustainable development–a case study of environmental education and awareness training in Hong Kong. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2017, 26, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Mi, L.; Xu, T.; Wang, X.; Qiao, L. Whether and how role stressors trigger employee non-green behaviors? The mediating role of emotional exhaustion. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2024, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).