Sustainability Measures of the Apparel Industry: A Longitudinal Analysis of Apparel Corporations’ Sustainability Efforts

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Sustainability Reports

2.2. Sustainability Measuring Indices

2.3. Sustainable Apparel Coalition (SAC)

2.4. Global Reporting Initiative (GRI)

2.5. Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP)

3. Materials and Methods

Data and Analysis

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Environmental Protection Agency. Overview of Greenhouse Gases. 2017. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/overview-greenhouse-gases (accessed on 8 January 2018).

- UNFCCC. U.N. Helps Fashion Industry Shift to Low Carbon; United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change: Bonn, Germany, 2018; Available online: https://unfccc.int/news/un-helps-fashion-industry-shift-to-low-carbon (accessed on 7 March 2019).

- Chen, X.; Memon, H.A.; Wang, Y.; Marriam, I.; Tebyetekerwa, M. Circular economy and sustainability of the clothing and textile industry. Mater. Circ. Econ. 2021, 3, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Fashion and the Circular Economy. 2017. Available online: https://archive.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/explore/fashion-and-the-circular-economy (accessed on 8 January 2018).

- Kunz, G.I.; Garner, M.B. Going Global: The Textile and Apparel Industry; Fairchild Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- World Wildlife Fund. Thirsty Crops. 2013. Available online: https://assets.wwf.org.uk/downloads/thirstycrops.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2020).

- Singha, K.; Pandit, P.; Maity, S.; Sharma, S.R. Harmful environmental effects for textile chemical dyeing practice. In Green Chemistry for Sustainable Textiles; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2021; pp. 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willsher, I. What Is Polyester Made of and Is It Ever Sustainable? Utopia. 2022. Available online: https://utopia.org/guide/what-is-polyester-made-of-and-is-it-ever-sustainable/ (accessed on 17 June 2023).

- Karthik, T.; Rathinamoorthy, R. Sustainable synthetic fibre production. In Sustainable Fibres and Textiles; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 191–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiti, R. Fast Fashion: Its Detrimental Effect on the Environment. Earth.Org. 2024. Available online: https://earth.org/fast-fashions-detrimental-effect-on-the-environment/ (accessed on 13 April 2024).

- Algamal, A. New Shocking Facts about the Impact of Fast Fashion on Our Climate; Oxfam GB: Oxford, UK, 2019; Available online: https://www.oxfam.org.uk/oxfam-in-action/oxfam-blog/new-shocking-facts-about-the-impact-of-fast-fashion-on-our-climate/ (accessed on 12 December 2023).

- Press, R. Your Clothes Can Have an Afterlife; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.nist.gov/news-events/news/2022/05/your-clothes-can-have-afterlife (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Wolfe, I. Textile Dyes Pollution: The Truth about Fashion’s Toxic Colours. Good on You. 2024. Available online: https://goodonyou.eco/textile-dyes-pollution/ (accessed on 5 March 2024).

- Aras, G.; Crowther, D. Corporate sustainability reporting: A study in disingenuity? J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 87, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations General Assembly. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future. 1987. Available online: http://www.un-documents.net (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- Nogueira, E.; Gomes, S.; Lopes, J.M. Triple bottom line, sustainability, and economic development: What binds them together? A bibliometric approach. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C. Sustainability and Sustainable Development. 2018. Available online: http://www.circularecology.com/sustainability-and-sustainable-development.html (accessed on 9 July 2024).

- Fletcher, K.; Grose, L. Fashion & Sustainability: Design for Change; Laurence King Publishing: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Diddi, S.; Niehm, L.S. Corporate Social Responsibility in the Retail Apparel Context: Exploring Consumers’ Personal and Normative Influences on Patronage Intentions. J. Mark. Channels 2016, 23, 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omair, S.; Khizar HM, U.; Majeed, O.; Iqbal, M.J. Sustainability: Concept clarification and theory. In Corporate Sustainability in Africa; Adomako, S., Danso, A., Boateng, A., Eds.; Palgrave Studies in African Leadership; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2023; pp. 375–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, M.; Guan, D.; Yang, Z. The carbon footprint of fast fashion consumption and mitigation strategies: A case study of jeans. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 924, 171508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landi, F.; Fabiani, C.; Pioppi, B.; Pisello, A.L. Sustainable management in the slow fashion industry: Carbon footprint of an Italian brand. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2023, 28, 1229–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.; Li, Q.; Dong, C.; Perry, P. Sustainability issues in textile and apparel supply chains. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, N.R.; Chowdhury, P.; Paul, S.K. Sustainable practices and their antecedents in the apparel industry: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 256, 120472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business; Capstone Publishing: Mankato, MN, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Leavoy, P. What Motivates Companies to Produce Sustainability Reports? LNS Research. 2015. Available online: http://www.lnsresearch.com/ (accessed on 4 March 2018).

- Ferns, B.; Emelianova, O.; Sethi, S.P. In his own words: The effectiveness of CEO as spokesperson on CSR-sustainability issues–Analysis of data from the Sethi CSR Monitor©. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2008, 11, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Reporting Initiative. What Is Sustainability Reporting? 2013. Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org (accessed on 9 May 2023).

- Gray, R.; Owen, D.; Adams, C. Accounting and Accountability: Changes and Challenges in Corporate Social Environmental Reporting, 1st ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Deegan, C. Financial Accounting Theory; McGraw-Hill: Sydney, Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rafi, T. Why Sustainability Is Crucial for Corporate Strategy. World Economic Forum. June 2022. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/06/why-sustainability-is-crucial-for-corporate-strategy/ (accessed on 17 June 2023).

- Eccles, R.G.; Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. The impact of corporate sustainability on organizational processes and performance. Manag. Sci. 2014, 60, 2835–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KPMG. The Time Has Come: The KPMG Survey of Sustainability Reporting 2020; KPMG International: Amstelveen, The Netherlands, 2020; Available online: https://kpmg.com/xx/en/home/insights/2020/11/the-time-has-come-survey-of-sustainability-reporting.html (accessed on 17 June 2022).

- Clark, G.L.; Feiner, A.; Viehs, M. From the Stockholder to the Stakeholder: How Sustainability Can Drive Financial Outperformance; Oxford University: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Giese, G.; Lee, L.E.; Melas, D.; Nagy, Z.; Nishikawa, L. Foundations of ESG investing: How ESG affects equity valuation, risk, and performance. J. Portf. Manag. 2019, 45, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RobecoSAM. The sustainability yearbook 2019. In 2018 Annual Corporate Sustainability Assessment; RobecoSAM: Zurich, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Perez, L.; Hunt, D.V.; Samandari, H.; Nuttall, R.; Biniek, K. Does ESG Really Matter—And Why? McKinsey & Company: Chicago, FL, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/sustainability/our-insights/does-esg-really-matter-and-why (accessed on 13 April 2024).

- Cascale. 2024. Available online: https://cascale.org/ (accessed on 3 March 2024).

- Carbon Disclosure Project. 2017. Available online: https://www.cdp.net (accessed on 23 September 2017).

- Global Reporting Initiative. GRI Standards. 2024. Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org/standards (accessed on 14 February 2024).

- Thumi, B. Sustainable Apparel Coalition rebrands as Cascale. Business Wire. 2024. Available online: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20240221828872/en/Sustainable-Apparel-Coalition-Rebrands-as-Cascale/ (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- Bruce, A. Sustainable Apparel Coalition rebrands as Cascale. Apparelist. 2024. Available online: https://www.apparelist.com/2024/02/27/sustainable-apparel-coalition-rebrands-as-cascale/ (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- Sala, S.; Ciuffo, B.; Nijkamp, P. A systemic framework for sustainability assessment. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 119, 314–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, X.; Cao, H. A comparison between consumer and industry perspectives on sustainable practices throughout the apparel product lifecycle. In Proceedings of the International Textile and Apparel Association (ITAA) Annual Conference, St. Petersburg, FL, USA, 14–18 November 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Deloitte. Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). IAS Plus. 2013. Available online: https://www.iasplus.com/en/resources/sustainability/gri (accessed on 8 January 2024).

- GRI 1; Foundation. Global Reporting Initiative: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021.

- GRI 2; General Disclosures. Global Reporting Initiative: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021.

- GRI 3; Management Approach. Global Reporting Initiative: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021.

- GRI 201; Economic Performance. Global Reporting Initiative: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016.

- GRI 302; Energy. Global Reporting Initiative: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016.

- GRI 305; Emissions. Global Reporting Initiative: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016.

- GRI 401; Employment. Global Reporting Initiative: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016.

- GRI 403; Occupational Health and Safety. Global Reporting Initiative: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018.

- Belkhir, L.; Bernard, S.; Abdelgadir, S. Does GRI reporting impact environmental sustainability? A cross-industry analysis of CO2 emissions performance between GRI-reporting and non-reporting companies. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2017, 28, 138–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncalves, A.; Silva, C. Looking for sustainability scoring in apparel: A review on environmental footprint, social impacts and transparency. Energies 2021, 14, 3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, P.; Rhodes, H.; Stickler, D. Three ways to leverage the many benefits of virtual collaboration. Sustain. Brands 2017, 22, 2017. Available online: https://sustainablebrands.com/read/product-service-design-innovation/three-ways-to-leverage-the-many-benefits-of-virtual-collaboration (accessed on 16 April 2018).

- Depoers, F.; Jeanjean, T.; Jerome, T. Voluntary disclosure of greenhouse gas emissions: Contrasting the Carbon Disclosure Project and corporate reports. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 134, 445–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaifi, K.; Elnahass, M.; Salama, A. Carbon disclosure and financial performance: UK environmental policy. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 29, 711–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gap Inc. Sustainability. 2024. Available online: https://www.gapinc.com/en-us/values/sustainability (accessed on 14 February 2024).

- Hanes Inc. HanesBrands Announces 2030 Global Sustainability Goals Focused on People, Planet, and Product. 2020. Available online: https://newsroom.hanesbrands.com (accessed on 20 June 2021).

- JC Penney. Corporate Responsibility. 2024. Available online: https://companyblog.jcpenney.com/corporateresponsibility/ (accessed on 14 February 2024).

- Kohl’s Corp. Environmental Sustainability. 2023. Available online: https://corporate.kohls.com (accessed on 17 August 2023).

- Macy’s Inc. Investors. 2023. Available online: https://www.macysinc.com (accessed on 17 June 2023).

- Nike Inc. Move to Zero. 2024. Available online: https://www.nike.com/sustainability (accessed on 13 April 2024).

- Nordstrom Inc. Corporate Social Responsibility. 2024. Available online: https://www.nordstrom.com (accessed on 13 April 2024).

- PVH Corp. Responsibility. 2024. Available online: https://www.pvh.com (accessed on 17 June 2023).

- TJX Companies Inc. Corporate Responsibility. 2024. Available online: https://www.tjx.com (accessed on 13 April 2024).

- VF Corp. Responsibility. 2024. Available online: https://www.vfc.com (accessed on 17 June 2023).

- Fetisov, V.; Gonopolsky, A.M.; Davardoost, H.; Ghanbari, A.R.; Mohammadi, A. Regulation and impact of VOC and CO2 emissions on low-carbon energy systems resilient to climate change: A case study on an environmental issue in the oil and gas industry. Energy Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1516–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNFCCC. Fashion Charter Informational Pack; United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change: Bonn, Germany, 2023; Available online: https://unfccc.int/documents/632723 (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- Karedla, Y.; Mishra, R.; Patel, N. The impact of economic growth, trade openness and manufacturing on CO2 emissions in India: An autoregressive distributive lag (ARDL) bounds test approach. J. Econ. Financ. Adm. Sci. 2021, 26, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.; Min, W. Research on the control path and countermeasures of net CO2 emissions in central China—Represented by Jiangxi Province. Environ. Technol. 2022, 43, 3367–3378. [Google Scholar]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Circular Economy. 2016. Available online: https://ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/ (accessed on 8 January 2018).

- Deloitte. 2021 Climate Check: Business’ Views on Environmental Sustainability. 2021. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/xe/en/pages/risk/articles/2021-climate-check-business-views-on-environmental-sustainability.html (accessed on 5 March 2024).

- De Pablo Valenciano, J. Sustainability and Retail: Analysis of Global Research. Sustainability 2019, 11, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Wildlife Fund. Freshwater Initiatives. 2020. Available online: https://www.worldwildlife.org/initiatives/freshwater (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- International Energy Agency. Renewables 2022; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2022; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/renewables-2022 (accessed on 17 August 2023).

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goal 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities. 2015. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/cities/ (accessed on 4 March 2018).

- Stockholm Convention. Protecting Human Health and the Environment from Persistent Organic Pollutants. 2001. Available online: https://www.pops.int/ (accessed on 4 March 2018).

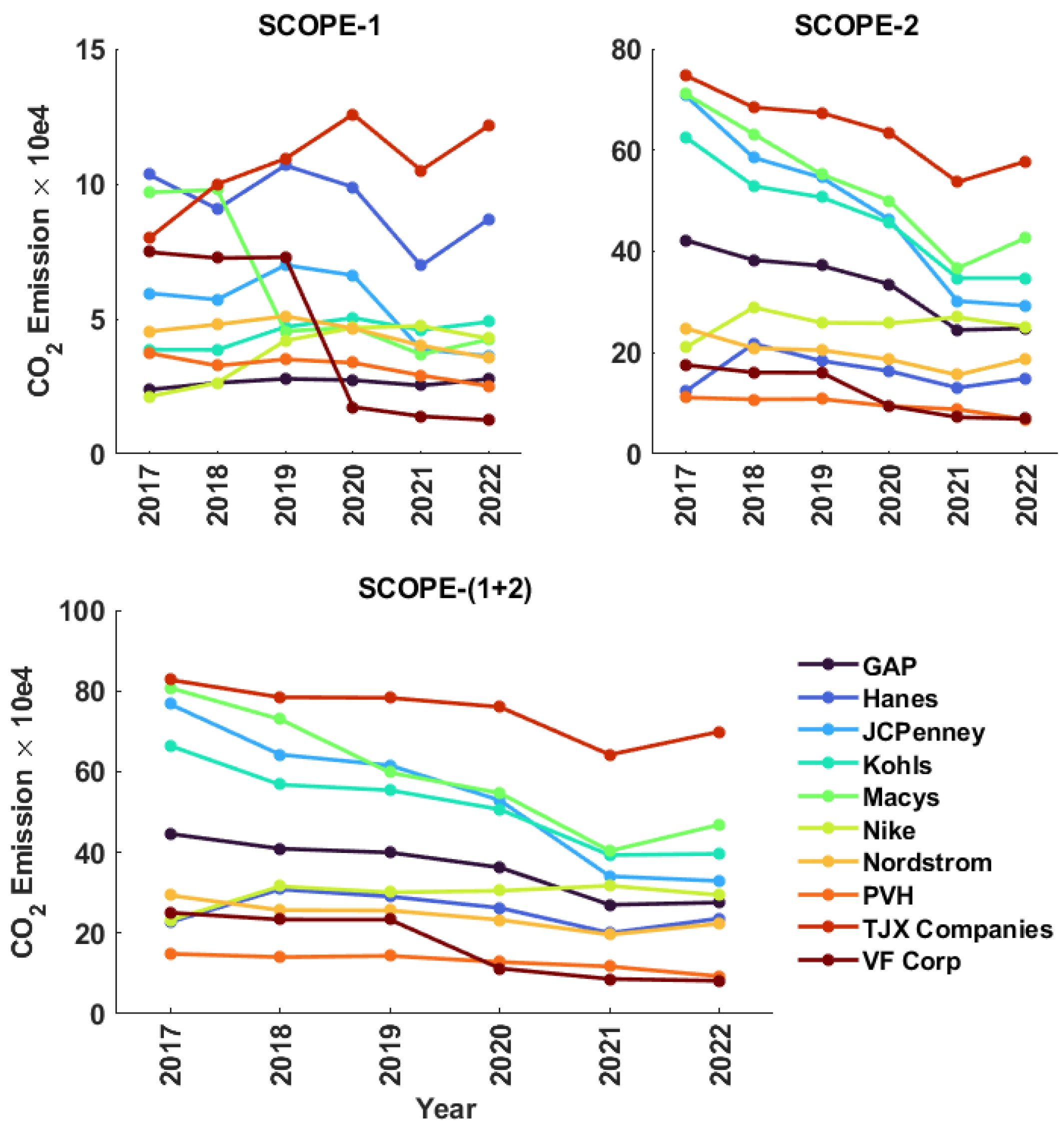

| Year | Scope 1 CO2 (Metric Tons) | Scope 2 CO2 (Metric Tons) | Scope 1 and 2 Combined CO2 (Metric Tons) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 58,089.26 | 408,253.2 | 466,342.4 |

| 2018 | 58,998.2 | 379,827.9 | 438,826.1 |

| 2019 | 60,726.99 | 356,675.5 | 417,402.4 |

| 2020 | 55,964.77 | 318,626.5 | 374,591.3 |

| 2021 | 45,215.76 | 251,542.1 | 296,757.9 |

| 2022 | 48,000.14 | 261,812.3 | 309,812.4 |

| Corporation | Water | Energy | Transportation | Waste Recycling | Chemical Management |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gap Inc. [59] | Implementing water-saving techniques in denim manufacturing | Investing in renewable energy sources and energy efficiency in stores and facilities | Optimizing logistics to reduce transportation emissions | Comprehensive waste reduction and recycling programs in stores and distribution centers | Reducing hazardous chemicals in products and manufacturing processes |

| Hanes Inc. [60] | Water conservation practices in textile production, such as using recycled water | Utilizing energy-efficient machinery and transitioning to renewable energy in manufacturing plants | Developing a sustainable transportation fleet, including electric vehicles | Implementing extensive recycling programs for textile waste and packaging materials | Ensuring safer chemical management and compliance with regulatory standards in the supply chain |

| JC Penney [61] | Water efficiency initiatives in stores and distribution centers | Implementing energy-saving measures, such as LED lighting and energy management systems | Adopting eco-friendly transportation options and optimizing delivery routes | Recycling programs for cardboard, plastic, and other materials in stores | Reducing the use of harmful chemicals in products through supplier partnerships |

| Kohl’s Corp. [62] | Water efficiency programs in operations, including low-flow fixtures | Sourcing renewable energy and improving energy efficiency in facilities | Reducing transportation emissions through improved logistics and fuel-efficient vehicles | Comprehensive waste recycling initiatives, diverting waste from landfills | Implementing safe chemical practices and reducing chemical use in products |

| Macy’s Inc. [63] | Implementing water-saving technologies in stores | Energy conservation efforts, including the use of renewable energy and energy-efficient lighting | Sustainable transportation initiatives, including optimizing logistics | Waste management and recycling programs, focusing on reducing landfill waste | Managing chemicals in products to ensure safety and compliance |

| Nike Inc. [64] | Reducing water usage in textile dyeing and finishing processes by 25% | Increasing the use of renewable energy and improving energy efficiency in manufacturing and retail operations | Reducing emissions from logistics and transportation through optimized delivery networks | Achieving zero waste to landfill in the supply chain and recycling at least 80% of waste | Innovating in sustainable chemistry to reduce environmental impact |

| Nordstrom Inc. [65] | Reducing water consumption in operations and supply chain | Implementing energy-efficient practices and sourcing renewable energy | Promoting sustainable logistics and transportation practices | Extensive recycling programs in stores and supply chains | Managing chemicals in products to ensure they are safe and environmentally friendly |

| PVH Corp. [66] | Implementing water-saving measures in manufacturing processes | Investing in green energy initiatives and improving energy efficiency across operations | Utilizing sustainable transportation options and optimizing logistics | Recycling initiatives across operations, including textile and packaging materials | Reducing hazardous chemicals and promoting safe chemical use in products |

| TJX Companies Inc. [67] | Water-saving measures in store operations and supply chain | Energy efficiency initiatives and renewable energy use in facilities | Reducing transportation emissions through efficient logistics and sustainable fleet management | Robust recycling programs, including recycling packaging materials and reducing waste | Implementing safe chemical use policies in products and supply chains |

| VF Corp. [68] | Promoting water stewardship and efficiency in the supply chain | Renewable energy sourcing and energy efficiency programs across facilities | Reducing transportation emissions through sustainable logistics practices | Circular economy initiatives and extensive waste recycling programs | Sustainable chemistry practices and reducing hazardous chemicals in products |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cheramie, L.; Balasubramanian, M. Sustainability Measures of the Apparel Industry: A Longitudinal Analysis of Apparel Corporations’ Sustainability Efforts. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6681. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16156681

Cheramie L, Balasubramanian M. Sustainability Measures of the Apparel Industry: A Longitudinal Analysis of Apparel Corporations’ Sustainability Efforts. Sustainability. 2024; 16(15):6681. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16156681

Chicago/Turabian StyleCheramie, Lance, and Mahendran Balasubramanian. 2024. "Sustainability Measures of the Apparel Industry: A Longitudinal Analysis of Apparel Corporations’ Sustainability Efforts" Sustainability 16, no. 15: 6681. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16156681

APA StyleCheramie, L., & Balasubramanian, M. (2024). Sustainability Measures of the Apparel Industry: A Longitudinal Analysis of Apparel Corporations’ Sustainability Efforts. Sustainability, 16(15), 6681. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16156681

_Li.png)