Abstract

The growing global concern over heat-related health risks, exacerbated by climate change, disproportionately affects low-income populations, particularly in tropical regions like Indonesia. This study investigates indoor thermal conditions in home-based enterprises (HBEs) within the informal urban settlements of Surakarta City, Indonesia, focusing on the struggle for thermal comfort under constrained conditions. By addressing the thermal comfort challenges in low-income urban housing, this research contributes to sustainable development goals, aiming to enhance living conditions in tropical climates. Our methodology included detailed field measurements of thermal comfort using standard indices in these dwellings, complemented by surveys and interviews to understand building designs, occupant behaviors, and adaptation strategies. Findings indicate that temperatures inside the dwellings frequently exceeded 30 °C during 50–60% of working hours, prompting residents to adopt coping strategies such as opening windows, adjusting work schedules, and utilizing shading devices. Space limitations necessitated multifunctional use of dwellings, exacerbating heat and humidity from activities like cooking and ironing. Despite reliance on natural ventilation, ineffective architectural layouts impeded airflow. This study highlights the urgent need for sustainable architectural solutions that accommodate the dual residential and commercial functions of these spaces, aiming to improve living conditions in such challenging environments.

1. Introduction

In recent years, global climate change, accompanied by the overarching issue of global warming, has risen as a prominent international concern, casting a shadow over both public health and overall well-being [1]. The repercussions of this transformation are evident in the increasing frequency of heatwaves, heavy rainfall, and other extreme weather events. Consequently, the heightened prevalence of elevated temperatures has been significantly associated with a surge in heat-related illnesses [2]. In response to this critical challenge, research into the health hazards stemming from rising temperatures due to climate change [3,4], along with efforts to mitigate these risks [5], has seen substantial growth. Nevertheless, a considerable portion of this research has primarily concentrated on mid-latitude regions, such as Europe, East Asia, and the USA. In contrast, South-East Asia, located within the tropical and subtropical zones, grapples with persistent high temperatures throughout the year [6]. In this region, low-income households often contend with substandard living conditions lacking mechanical cooling devices and adequate infrastructure, rendering them more susceptible to a myriad of health risks [7,8]. With such a background, the indoor thermal conditions of naturally ventilated residential buildings in South-East Asia and other developing regions with hot climates have been extensively investigated, focusing on occupants’ thermal comfort, health, and living quality. For example, Kubota et al. [9] conducted a field experiment in typical terrace houses to examine the effectiveness of ventilation as a passive cooling method. They found that night ventilation improves thermal comfort but also emphasized the need for indoor humidity control during the daytime. Toe and Kubota [10] measured indoor thermal conditions in traditional Malay houses in Malaysia under natural ventilation and revealed that indoor air temperatures were generally higher than outdoor temperatures, underscoring the importance of passive cooling techniques. Djamila and Kumaresan [11] conducted a field survey of indoor thermal comfort among 890 occupants and assessed physical indoor thermal variables in non-air-conditioned residences in Kota Kinabalu, Malaysia. They suggested that high indoor temperatures necessitate passive cooling strategies in building designs. Irakoze and Kim [12] evaluated the indoor thermal conditions of three main urban housing types—informal settlements, planned low-income housing, and modern urban housing—in Kigali, Rwanda, located in a tropical highland climate zone, using building energy simulations. Naicker and Mathee [13] reported high heat risk based on indoor temperature measurements in 100 low-cost houses in South Africa.

Indonesia, home to a vast population of 270 million in South-East Asia, has witnessed robust economic growth in recent years. This economic expansion has run in parallel with urbanization, resulting in the urban population accounting for 55% of the total population in 2018 [14]. Projections indicate that urbanization will continue, with an estimated three-quarters of the total population expected to dwell in cities by 2045 [15]. Consequently, the confluence of global warming and the urban heat island phenomenon is poised to amplify future threats of heat-related illnesses.

Simultaneously, the poverty rate in Indonesia stood at 9.5% in 2022, with an estimated 26.1 million individuals living below the poverty line [16]. Within urban areas, a significant number of impoverished households reside in informal settlements with inadequate infrastructure, often referred to as urban slums or ‘kampung’ in Indonesian [17]. Residents of these areas are exposed to a range of health and disaster risks due to the substandard conditions, other extreme weather, and the lack of air conditioning.

For instance, a study conducted by Murtyas et al. [18] involved field measurements of the indoor thermal conditions in 17 urban slum dwellings in Surakarta, Indonesia. Their findings revealed that the majority of these houses failed to meet the thermal comfort criteria established by ASHRAE55-2017 for most hours, resulting in a high risk of heatstroke. Based on the measured data from this study, Murtyas et al. [19] also reported a high mold risk in low-cost housing due to high humidity and poor ventilation. Hildebrandt et al. [20] investigated the indoor air quality and health conditions of occupants in newly constructed high-rise apartments and traditional kampung houses in Surabaya. They found that while high-rise apartments had higher levels of formaldehyde and total volatile organic compounds, mold issues were more severe in kampung housing due to higher humidity and poor ventilation. Similarly, Hanief et al. [21] reported field measurements of indoor air quality and humidity in informal settlements in Bandung, Indonesia, which highlighted the elevated mold risk associated with low construction quality and the hot, humid climate. Furthermore, Prihardanu et al. [22] reviewed recent field studies on indoor air quality of housing and relevant national regulations and standards, suggesting inadequate ventilation in housing and gaps in the implementation of mandatory regulations.

Meanwhile, several studies have indicated that a significant proportion of residents in informal settlements in developing countries are engaged in home-based work, one of the three typical urban informal occupational groups alongside street vendors and waste pickers [23,24]. Home-based workers, particularly those who are self-employed or sub-contracted, often find themselves more vulnerable to the influence of the macroeconomic environment [25]. Furthermore, they are exposed to substandard indoor working conditions due to low-quality housing [26] and hazardous pollutants from indoor manufacturing activities [27]. In 2006, Tipple [28] reported the results of surveys of home-based enterprise (HBE) households in Cochabamba, Bolivia; New Delhi, India; Surabaya, Indonesia; and Pretoria, South Africa, highlighting their poor working conditions and various health risks. Almost 20 years after the publication of this paper, working and living conditions in HBEs continue to be a problem in many developing countries.

In the case of Indonesia, urban informal settlements serve as both living spaces and HBEs, encompassing a variety of small, informal businesses that support household livelihoods. The characteristics of HBEs within informal settlements in Indonesia have been studied in the fields of labor economics [25,29] occupational public health [30], and urban/architectural planning [31,32,33,34]. For example, Kusumaningdyah et al. conducted a field survey of HBE housing in urban slums in Surakarta City [35]. Their research identified the diversity of businesses and how home-based workers utilize their limited small housing space for multiple functions, including both living and business activities.

The integration of HBEs in small, low-cost housing in Indonesia presents unique features of adaptive space usage, as explored by several key studies. Sihombing [36,37] reported that the architecture of kampung houses often evolves to incorporate in-house businesses, such as “warung” (small stalls), laundry services, food shops, and other commercial ventures to meet local demands. Spaces within HBE dwellings are notably flexible, serving multiple purposes—ranging from a workspace to a living room—depending on the time of day. Prakoso and Dewi [38] highlighted the use of flexible spaces to reduce conflicts between living and working areas. Suparwoko and Raharjo [39] examined the blend of local and Western influences in Yogyakarta HBEs catering to tourists. Putri et al. [40] observed that residents in Kampung Lio, Depok, adapt their homes for multiple businesses. Lastly, Putra et al. [41] investigated housing activities in Bandung, emphasizing the need for spacious and flexible housing designs to accommodate various domestic and social activities. Together, these studies underline the necessity of adaptable housing designs to support the dual function of homes as residential and commercial spaces.

However, to our knowledge, the indoor thermal environment of HBE housing in not only Indonesia but also other developing regions has been rarely investigated. This is particularly significant as home-based workers spend a substantial amount of time within their substandard housing, in contrast to those working at locations other than a home. The quality of the indoor environment in HBE housing becomes even more critical for the health and well-being of these workers in slum housing. On the other hand, due to severe financial constraints, residents often face challenges in improving their living conditions. This financial burden can hinder their efforts to reduce heat-related health risks and mitigate the impacts of climate change.

With this background, the present study aims to address the research gap concerning indoor thermal conditions experienced by home-based workers in substandard HBE housing in Indonesia. By focusing on homes with varied HBE functions in Surakarta, Central Java, we explore three key research questions using both qualitative and quantitative approaches:

- (1)

- To what extent do the indoor climate conditions of HBE housing meet thermal comfort criteria as a working environment?

- (2)

- What problems exist in the design of HBE housing regarding the maintenance of good indoor air quality and thermal comfort?

- (3)

- What types of adaptation strategies have home workers employed to improve their environmental conditions in their current HBE housing, given economic constraints?

Specifically, we investigated HBE housing in four residential areas within the city of Surakarta. One area is an urban slum known as a kampung, while the other three are newly constructed low-rise residential districts planned to eliminate urban slums. We conducted in-depth interviews with residents and on-site observations in twelve dwellings across these districts to grasp the characteristics of housing design and occupants’ behaviors related to the indoor thermal comfort of home workers. For six of these dwellings, we estimated the time-series thermal comfort index during working hours using existing indoor thermal environment data and evaluated the fraction of thermal discomfort hours.

Regarding building design, various factors such as the thickness and size of materials, their thermal properties, and the ventilation efficiency between indoor and outdoor air critically influence indoor temperature. This mechanism can be modeled using building energy simulation techniques that solves dynamic thermal balance equations [42,43]. In fact, these simulations have been used to explore passive cooling designs effective in improving the indoor thermal environment of tropical residences [44]. However, such simulations are beyond the scope of this paper. In this exploratory study, we primarily analyze the characteristics of floor plans and the location and size of openings to determine if the design effectively ensures natural ventilation in non-air-conditioned HBE dwellings.

Overall, this study aims to contribute to the development of environmental improvement measures for HBE housing within Indonesia’s urban informal residential areas. This study aligns with the goals of sustainable development by addressing the environmental health and economic resilience of vulnerable populations. Improving thermal comfort and reducing heat risks in urban low-cost HBE housing not only enhance the well-being of residents but also support sustainable urban development.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Target Site

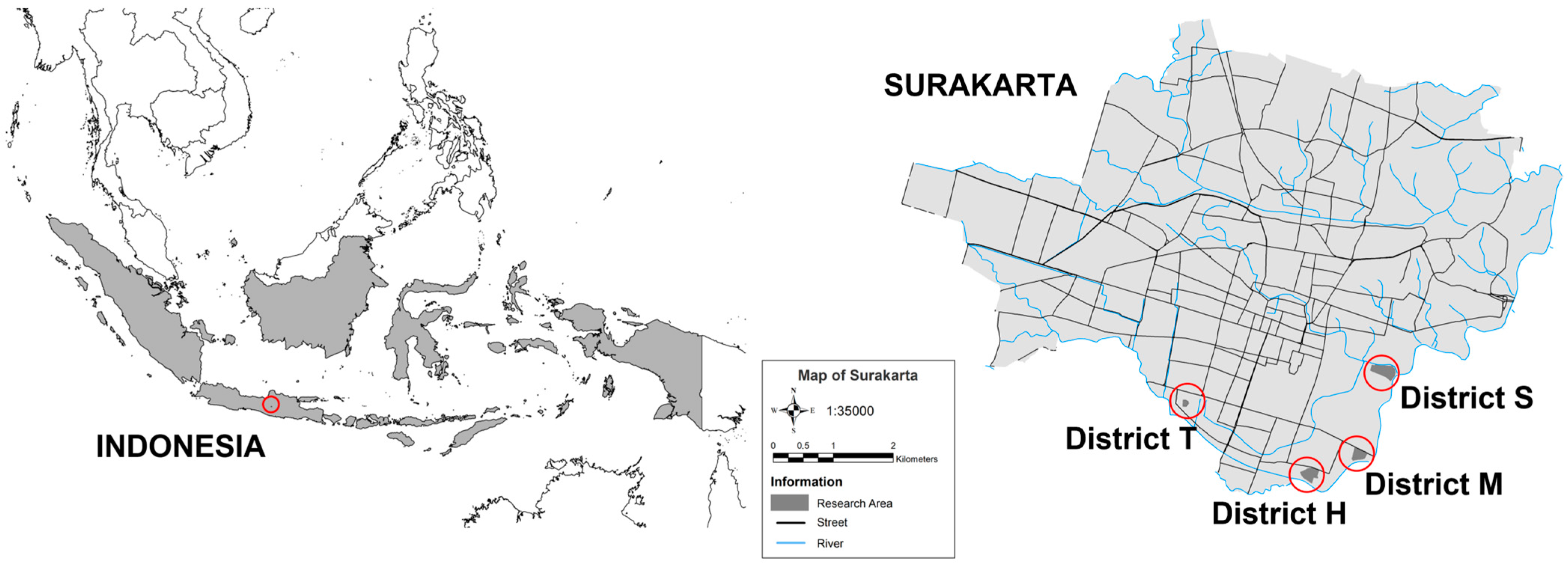

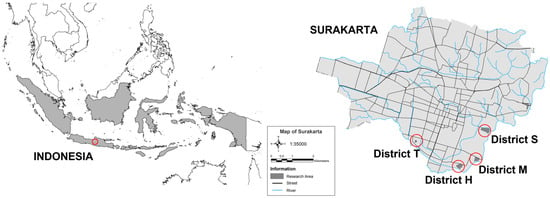

Surakarta City, commonly known as Solo, which was chosen as the field survey site for this study, stands prominently in Central Java, Indonesia, as shown in Figure 1. It is a provincial city with a population nearing 570,000. The selection of Surakarta is strategic due to its unique urban challenges; it encompasses an area of 46.72 km2, divided into 16 districts grouped into five blocks. Surakarta has a high population density, recorded at 11,194 people per square kilometer according to the 2024 BPS Statistics of Surakarta [16].

Figure 1.

Location of Surakarta City and surveyed districts.

As of 2020, a total area of 3.6 km2 has been officially recognized as urban slums, underscoring the city’s inclusion in the 2016 National Slum Improvement Programme (NUSP) initiated by the Indonesian Ministry of Public Works and Housing. Notably, Surakarta is among the 30 priority cities targeted by this program, reflecting its proactive stance in tackling urban slum proliferation and enhancing living conditions.

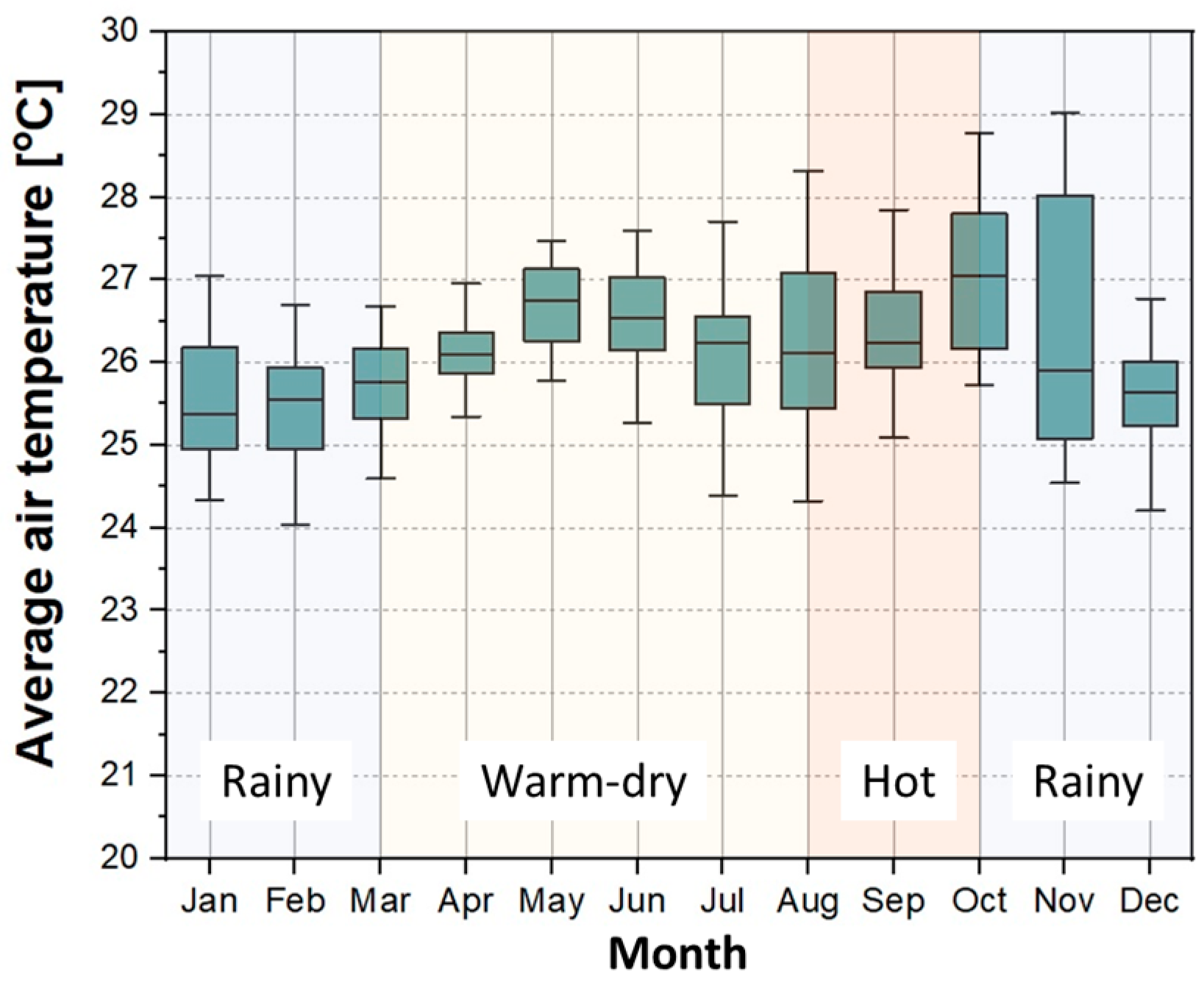

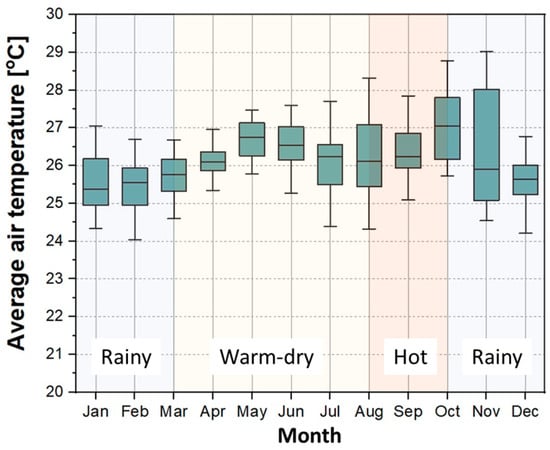

Surakarta City is situated within a tropical climate zone. Climate data from 2015 to 2018 show an average annual temperature of 26.9 °C and a total annual precipitation of 804.3 mm. As depicted in Figure 2, the city experiences minimal temperature variations throughout the year, characterized by a dry season lasting about five months (May–September) and a rainy season extending for seven months (October–April). The impact of such a hot and humid climate on the indoor thermal environment, particularly in urban slum housing with HBE functions, offers a pertinent context for our field survey.

Figure 2.

Daily high and low air temperature in Surakarta.

2.2. Surveyed Districts and Dwellings

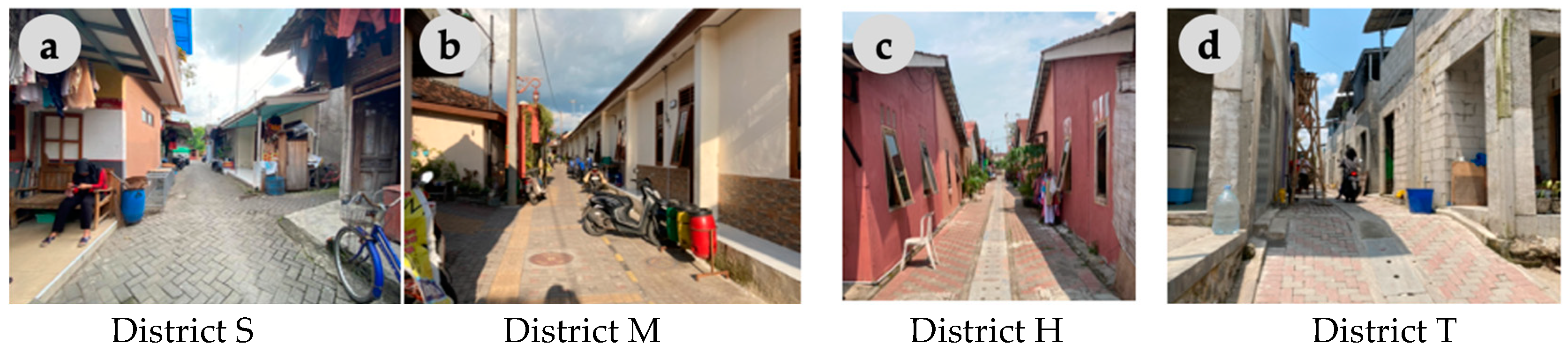

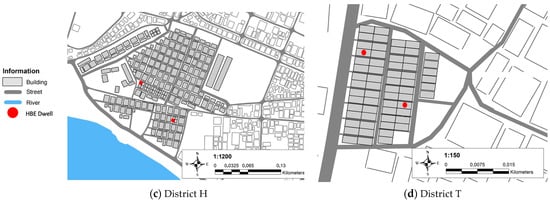

For our field survey, we selected twelve HBE dwellings located in four different districts, as shown in Figure 1. Figure 3 and Figure 4 illustrate the map and appearance of these districts. The first district is Rukun Warga (RW 13) within Kampung Sangkrah, located in Sangkrah, District of Pasar Kliwon, Surakarta (hereafter, District S). This area was selected as a typical urban informal residential district from 29 existing urban slum areas in Surakarta City. District S is notable for its high poverty rate of 30% [2331] and high population density, recorded at 16,101 people per square kilometer according to the 2024 BPS Statistics of Surakarta [45]. Figure 3a and Figure 4a display typical urban slum characteristics, with a dense aggregation of variously sized buildings and a notably irregular layout in relation to the surrounding streets.

Figure 3.

Site plan of target districts.

Figure 4.

Appearance of surveyed districts.

In addition, we adopted three districts from four newly built areas under the urban slum upgrading projects initiative by Surakarta City, known as the Kota Tanpa Kumuh (KOTAKU) program. These districts are Kampung Metal Mojo (hereafter, District M), Kampung HP 00001 (hereafter, District H), and Kampung Tipes (hereafter, District T), which are located within 5 km of District S. The selection criteria for these three districts were the contrasting geometries of their architectural designs. As shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4, Districts M, H, and T represent newly built residential areas aimed at upgrading sub-standard urban slum settlements. In District M, long row-house-style buildings were constructed along the street, housing a total of 56 dwelling units in 2021. Conversely, District H consists of townhouses, with a total of 523 dwelling units built since 2021. Meanwhile, in District T, a total of 63 households reside in townhouses, consisting of four units constructed in 2022.

In Districts M, H, and T, the columns and beams made of concrete modules, roofs, and concrete-block walls were constructed at the municipality’s expense. In contrast, the residents were responsible for finishing the interiors and exteriors, as well as installing window sashes and ventilation openings. Consequently, the size and position of windows and ventilation openings vary from one dwelling to another.

In our study, we meticulously selected twelve houses, all situated on legally owned properties to capture a broad representation of HBE housing within Surakarta City. The selected HBE dwellings encompass diverse business types and building conditions, as outlined in Table 1. The majority of these dwellings are modestly sized, ranging from 30 to 100 m2. Dwellings newly constructed by slum upgrading projects tend to be smaller, reflecting financial constraints.

Table 1.

Outline of surveyed HBE dwellings.

Notably, the original dwelling units of District H (H1 and H2) feature two bedrooms and a living room. Similarly, dwellings in Districts M and T are designed with a living room and a single bedroom. The dimensions are significantly modest, given the number of occupants. Approximately half of the surveyed dwellings are single-story, although three have had loft spaces added by occupants to meet their needs. The majority of the households are classified as “low” in terms of household income compared to the regional average. In contrast, to provide a comparative perspective, our study includes one larger residence owned by a middle- to high-income household (S1).

The study involves not only conducting interviews with residents but also entering the residences—a highly private space—for observations and taking photographs. To facilitate this, we recruited twelve households willing to cooperate with the study, having established a trusting relationship with the residents and communities through repeated visits over the past five years.

Considering that the number of substandard dwellings in Surakarta City was approximately 12,000 as of 2022 [46] (with the number of substandard HBE dwellings not specifically reported), our survey sample of twelve households is extremely small and cannot be considered statistically representative. Nevertheless, this exploratory study is a first attempt to understand the actual indoor thermal environment of HBE housing in Indonesia and to elucidate the design of HBE housing and occupant behaviors as dominant factors affecting the indoor thermal environment. Therefore, we believe this in-depth survey of twelve HBE dwellings has significant academic value despite its limited sample size.

2.3. Observation and Interview on Occupants’ Behaviors and Architectural Setting of the Target Dwellings

We conducted qualitative interviews at six dwellings located in District S from March to May 2023 and at the remaining six dwellings from September to November 2023. We interviewed the head of the household in each house, focusing on their lifestyle, perceptions of indoor thermal conditions and functional use of spaces. For this interview, we prepared 15 questions divided into four sections. The first section collected demographic information, such as gender, age, and occupation of each household member. The second section explored perceptions of the condition and quality of the building. In the third section, we explored the spatial–temporal dynamics of HBE activities. We specifically focused on the daily schedules of home-based workers, inquiring about the range of activities—including work, social interactions, meals, sleep, and leisure—carried out throughout the day. Additionally, we gathered data on specific locations within the home where these activities typically take place. The last section was on lifestyle factors that affect indoor thermal conditions, including appliance ownership, usage schedules, and window and door opening habits. Each interview, which lasted for approximately 30 min, varied in length depending on the number of household members. Conducted in Indonesian, the interviews were recorded to ensure efficiency and accuracy. We aimed to create a relaxed atmosphere for the respondents, encouraging them to express their thoughts and opinions on their lives, work, and housing freely, without diverting from their initial responses.

In addition, the design, including the geometry and material of each component, layout of the furniture, and usage of space in each dwelling were meticulously documented through photographs, sketches, and drawings. The major variables used for analysis are shown in Table 2. Past field measurements in a non-air-conditioned terrace house in Malaysia, which shares similar climate conditions with our current research site, revealed the significant impact of natural ventilation on space cooling [45]. Therefore, the presence and size of openings exposed to the outside air in each room were included in our analysis.

Table 2.

Observed building-related variables.

2.4. Field Measurement and Questionary Survey on Indoor Thermal Conditions

The field measurement of indoor air temperature and relative humidity was conducted at six dwellings of District S from 26 March to 5 May, 2019, over 41 days with an interval of 10 min to assess indoor thermal environment conditions. The details of the measurement procedure have been reported in [18]. The measurement period coincided with the transition between the wet and dry seasons. As shown in Figure 2, due to the tropical climate near the equator, the annual variation in Surakarta City’s climate is minimal compared to mid-latitude regions. Therefore, the data collected over the 41 days are considered representative for evaluating the indoor thermal environment in this hot and humid region.

By using the measured time-series indoor air temperature and relative humidity, we calculated the thermal comfort metrics in each dwelling. Specifically, operative temperature, predicted mean vote (PMV), and predicted percentage dissatisfied (PPD) based on ASHRAE 55 [47] were adopted for assessing thermal exposure of HBE workers during working hours. The radiative temperature was assumed to be identical to the indoor air temperature, whilst indoor wind speed was assumed to be 0.15 m/s. In addition, the thermal insulation of closing was assumed to be 0.5 clo. The daily variation in the metabolic rate for each dwelling was determined based on the occupants’ HBE working schedule and type of behaviors collected by the interviews according to the four categories adopted in ASHRAE 55: lifting/packing (MET = 2.1), walking (MET = 1.7), standing (MET = 1.4), and seated position (MET = 1.1).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Thermal Comfort Assessment Based on PMV and PPD Indices

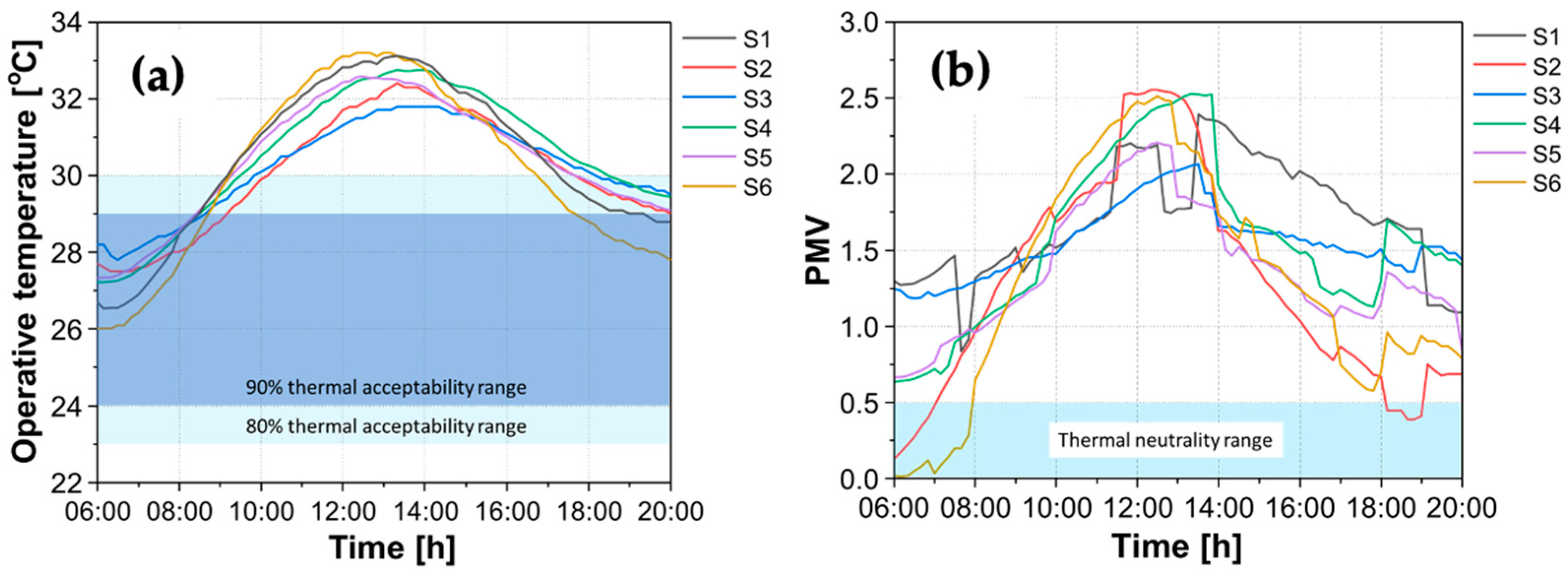

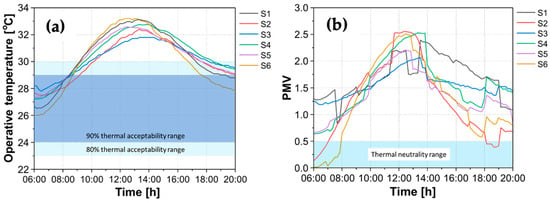

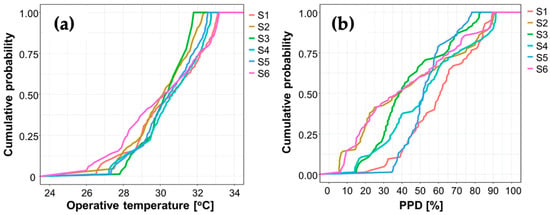

Figure 5 illustrates the daily fluctuations in indoor operative temperature and PMV, averaged over 41 measurement days, for the six residential dwellings. The figure also depicts the adaptive thermal comfort ranges for 80% and 90% acceptability, as well as the thermal neutrality range indicated by a PMV below 0.5.

Figure 5.

(a) Averaged daily fluctuation in operative temperature and (b) PMV at six dwellings of District S during HBE working hours.

The operative temperatures in all six dwellings correlate with the daily changes in outdoor air temperature and solar radiation, starting to rise at 6 a.m. and peaking between noon and 2 p.m., before decreasing. After 9–10 a.m., the operative temperatures exceed the 80% thermal comfort threshold, remaining above 30 °C in the evening, between 5:00 and 6:00 p.m. The absence of air conditioning systems subjects occupants to these severe thermal conditions year-round, significantly impacting their comfort while working. The maximum daily operative temperatures vary slightly, by about 1 °C, from one dwelling to another. Notably, S1—occupied by middle- to high-income families with larger floor areas—and S6, which houses a grocery store, recorded especially high temperatures. A detailed analysis of the relationship between indoor thermal environments and the buildings’ thermophysical properties was previously reported in [18].

Similarly, the daily PMV trends reveal that higher ‘hot’ sensation values occur during daytime hours. However, the specific patterns vary significantly across the dwellings, influenced by the type of HBE and associated work intensity and schedules. For example, large stepwise changes in PMV at certain times reflect shifts in metabolic rates due to changes in HBE activities. A PMV below 0.5, indicating thermal comfort range, is observed for only 1–2 h in the early morning in dwellings S2 and S6. During most working hours, the PMV remains above 0.5, suggesting discomfort.

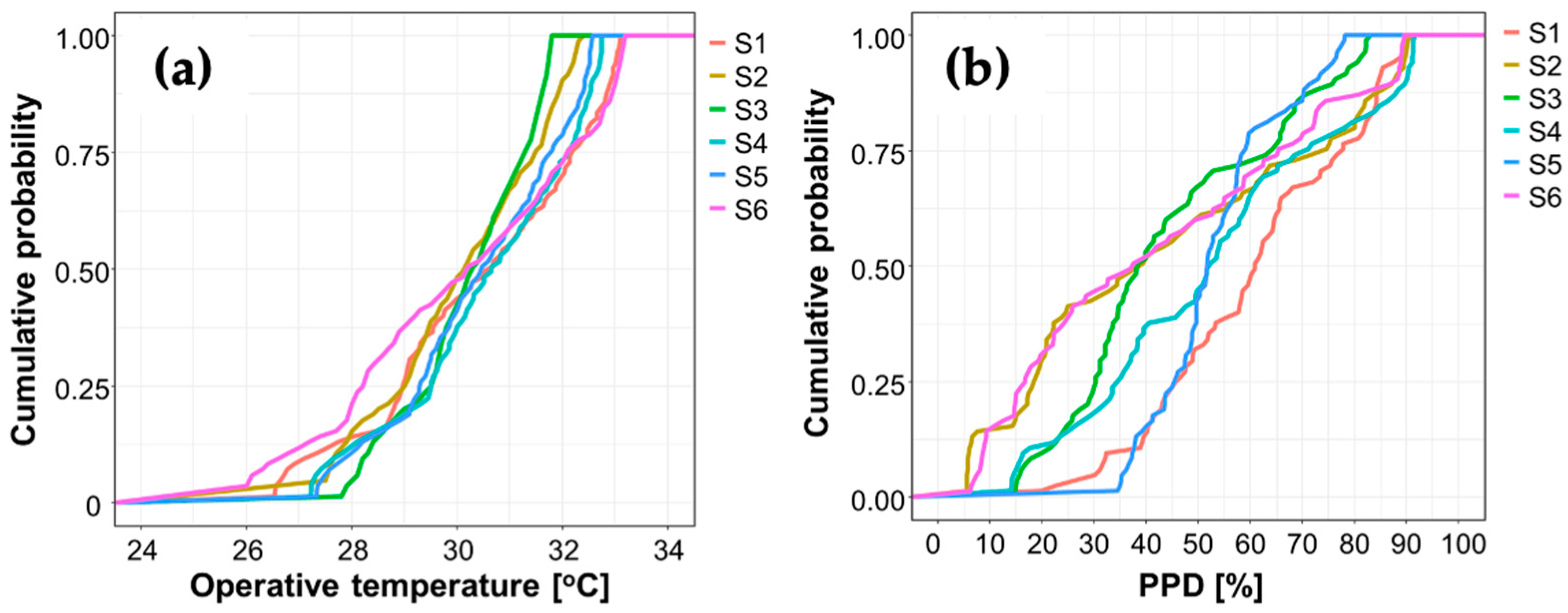

Figure 6 presents the cumulative probability density distributions of operative temperature and predicted percentage of discomfort (PPD) across the studied dwellings. While variations in operative temperature among the dwellings are modest, these temperatures surpass 30 °C during 50–60% of working hours in all six dwellings, indicating significant thermal discomfort.

Figure 6.

(a) Cumulative probability density distributions of operative temperatures and (b) PPD at six dwellings of District S during HBE working hours.

In contrast, the results of estimated PPD, which account for variations in metabolic rates due to different levels of work intensity, exhibit more pronounced differences among the dwellings. Notably, dwelling S1—characterized by its large floor area and status as a middle- to high-income household—displays the lowest thermal comfort levels. Here, a PPD exceeding 50% is observed for approximately 60% of the working hours, underscoring the thermal discomfort experienced. This is probably due to the slower temperature drop after sunset. The thick wall structure of S1, with its large heat capacity, retains heat longer than the other dwellings. In contrast, dwellings S2, S3, and S6, despite having smaller floor areas compared to S1, show a more favorable thermal comfort profile, with PPD values exceeding 50% for about 30% of the time. All the findings derived from three metrics suggest that the HBE spaces of these dwellings do not meet the thermal comfort criteria as working environments and highlight the necessity of improvement by affordable measures.

3.2. HBE Activities in Dwellings

Table 3 illustrates the working hours and spaces allocated for HBE activities within each dwelling, including the total floor area per occupant to assess building dimensions. It reveals that half of the surveyed dwellings have a relatively small floor area in comparison to the number of occupants, indicating spatial limitations for these households. Consequently, occupants tend to stay and work from home for long periods, typically between 8 and 12 h. The floor area dedicated to HBE activities varies significantly among the dwellings, influenced by the type of business and building size. Specifically, in dwellings M2 and T1, households allocated a minimal space of less than 4 m2 for ironing service and shuttlecock manufacturing, respectively, to support their daily expenses, despite having a total floor area of only around 35 m2.

Table 3.

Space use for HBE activities in surveyed dwellings.

The ratio of HBE space to the total floor area emerges as a crucial indicator of living space quality [48,49], especially in homes with limited floor area. For dwellings with a total floor area per occupant less than 12 m2, this ratio ranged from 8.5% to 31.8%. Notably, the M1 household allocated nearly a third of its indoor space to tailoring activities. At dwelling S5, which had the highest HBE area ratio of 48.7%, residents routinely engaged in laundry activities, including washing, drying on clotheslines, and ironing clothes indoors daily.

The table also underscores the challenge of accommodating necessary business functions within constrained indoor spaces, as evidenced by the high ratio of multi-use space in the HBE area, exceeding 50% in the majority of surveyed dwellings. Remarkably, two households (S5 and T2) among the twelve utilized external spaces, such as porches in front of the entrance door, for their business activities to mitigate space shortages.

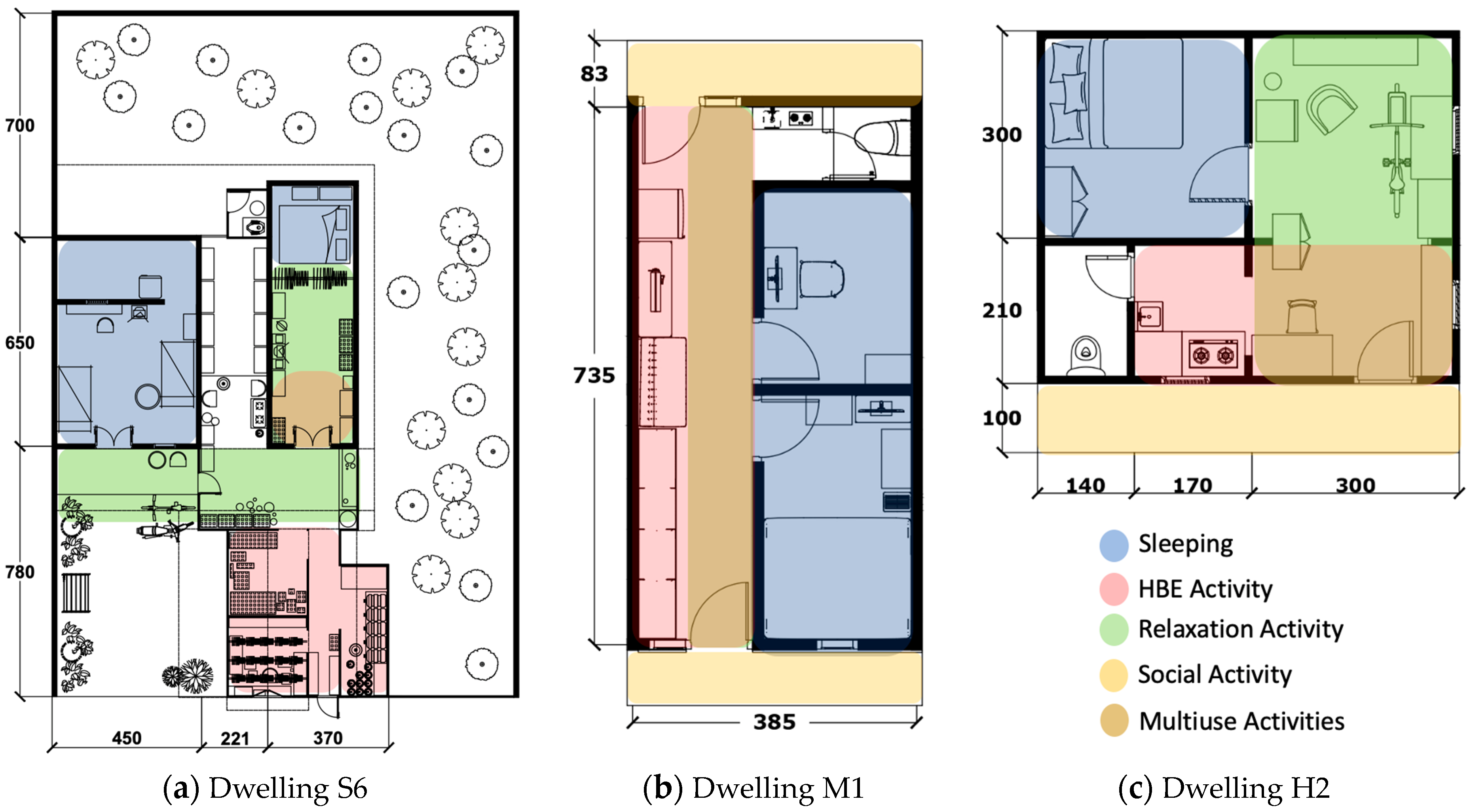

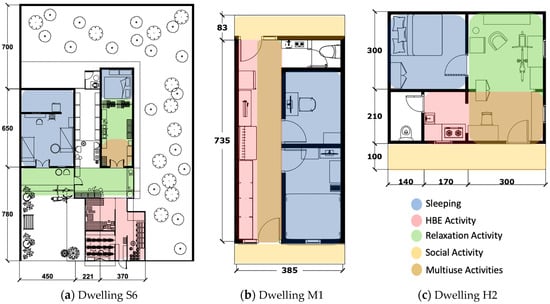

Figure 7 illustrates the contrasting floor plans of three dwellings with multi-use spaces in an HBE area. Dwelling S6 features a distinct space dedicated to running a grocery store, with clear separation between areas for daily activities, sleeping, and business operations. In contrast, in dwelling M1, distinguished by its elongated floor plan nestled between two adjacent homes, tailoring operations unfold within a space that multitasks as both a corridor and a living area. Spanning less than two meters width, this area contends with minimal free space due to the presence of furniture, a sewing machine, stacked fabrics and a mattress aligned against the wall. On the other hand, dwelling H2 integrates the kitchen as the core production area, serving both the household’s daily meal preparation and the food stall business. Furthermore, a significant portion of the living room, connected to the kitchen, is utilized for food preparation and arrangement during business hours. This area also serves as a space for family gatherings and relaxation throughout the day. These results are in line with the past study in Malang, Indonesia, reported by Pindo Tetuko [48].

Figure 7.

Floor plans of dwellings with multi-use space in HBE area.

3.3. Influence of HBE Activities on Indoor Physical Environment

Our field observations identify that specific activities within HBE, such as cooking and ironing, contribute to indoor heat and water vapor release, adversely affecting air quality and thermal comfort. In our study of twelve dwellings, six (S3, S5, S6, M2, H2, and T2) were identified as significant sources of these emissions due to their engagement in cooking and ironing activities (refer to Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Potential emission sources due to HBE activities.

The use duration of appliances in HBE settings frequently exceeds that in typical households. For example, ironing durations in dwellings S5 and M2 ranged from two to six hours. In dwelling M2, the use of a professional-grade propane-gas-powered iron resulted in substantial heat and steam emissions. Similarly, in dwellings S3, H2, and T2, where food is prepared for sale, prolonged cooking activities not only increased heat and water vapor but also released oil mist and odors, exacerbating indoor air quality challenges.

A pivotal finding is the absence of exhaust ventilation fans in not only kitchens, toilets, and bathrooms but also other spaces in the surveyed dwellings—a standard feature in homes within developed countries. Consequently, these HBE settings must rely on natural ventilation via doors and windows to mitigate indoor pollutants. This emphasizes the critical need for well-designed openings to facilitate effective natural ventilation, underscoring a key consideration in the management of indoor environments for HBE housing.

3.4. Building Characteristics Related to Natural Ventilation

Table 4 presents the building design features critically affecting natural ventilation effectiveness and the indoor thermal environment. Notably, 10 of the 12 dwellings surveyed are semi-detached or terraced, sharing two or three external walls with neighboring buildings. This configuration limits the availability of windows and other openings. This setup is especially common in the six dwellings within Districts M, H, and T, which were designed as part of a slum upgrading initiative and are constrained by limited land availability. In particular, dwelling M2 is enclosed by three other dwellings, with only the entrance-side wall exposed to the outside air. As a basic design policy for housing complexes in urban slum upgrading projects, each unit should be designed to face at least two sides to the outside air, regardless of land constraints. In contrast, dwellings S1 and S6 stand as detached houses, fully independent and with ample surrounding space—a rarity within the densely constructed District S.

Table 4.

Building characteristics of surveyed dwellings.

The shared external walls and resulting floor plans significantly reduce potential openings for natural ventilation, as highlighted in Table 4’s third column. Across the surveyed dwellings, rooms with more than two openings to the exterior are scarce, strongly reducing indoor air circulation. Specifically, eight dwellings have predominantly windowless sleeping areas, and three lack openings in kitchens—areas where ventilation is crucial due to high heat and vapor emissions—despite the absence of mechanical ventilation systems. Conversely, spaces designated for HBE activities or as living rooms generally feature two or more openings, ensuring better window area ratios for ventilation.

Dwelling S6, benefiting from a larger site with vacant surrounding land, nonetheless exhibits limited cross-ventilation potential due to minimal windows or openings on the far end and sides of external walls, as seen from the entrance (Figure 7a). As a result, the living room, kitchen, and bedroom have no windows. Additionally, as shown in Figure 9, even in the HBE space with openings in two locations, a large number of products are stacked from floor to ceiling in the extremely narrow store interior, causing poor air circulation. Such a design flaw, despite ample space with adequate privacy, might be attributed to incremental, low-cost renovations by residents without professional architectural input. This issue, alongside other floor plans detailed in Appendix A Figure A1, underscores that challenges in achieving effective cross-ventilation stem not only from site constraints but also from a lack of awareness among residents and local builders about the critical need for strategic opening design.

Figure 9.

A narrow store space occupied by many products (dwelling S6).

3.5. Occupants’ Behaviors to Adapt to Hot Indoor Environments

Table 5 showcases the strategies employed by occupants to enhance their indoor thermal comfort in the surveyed residences. A common practice across all households was the opening of windows and doors to improve natural ventilation during working hours. It is important to note, however, that natural ventilation does not consistently lead to lower indoor temperatures, as outdoor temperatures tend to be higher during these hours. Despite this, the practice remains prevalent in the HBE dwellings studied, which double as workspaces. Here, ventilation serves the dual purpose of expelling indoor pollutants—such as respiration byproducts, heat, vapor, and odors from activities like ironing and cooking—while also facilitating the dissipation of body heat through wind introduction. This has led to the adoption of natural ventilation as an established lifestyle practice within these communities.

Table 5.

Residents’ adaptation behaviors to the hot environment in surveyed dwellings. √ refer to a dwelling which took the countermeasure.

However, as discussed in Section 3.4, the architectural design of these dwellings poses a significant challenge to achieving a high air exchange rate between indoors and outdoors, primarily due to the limited availability of openings directly exposed to the outdoors. In an effort to mitigate this, occupants in three of the dwellings were observed positioning themselves near windows in living areas that featured larger openings, thereby maximizing the benefits of cross-ventilation.

Additionally, while two of the dwellings utilized air conditioners (ACs) for cooling a bedroom, the majority (10 out of 12) used fans as their cooling solution. Notably, occupants of dwelling H1 implemented solar shading on their porch to reduce heat gain during peak sunlight hours. Similarly, home workers in dwelling S5 adjusted their work schedules to sidestep the highest temperatures of the day.

Lastly, despite the daily habit of introducing outside air by opening windows and doors, and an apparent understanding of the benefits of natural ventilation among residents, cross ventilation is notably absent in the building designs, as shown in Table 4. The majority of the surveyed dwellings, whether in kampung areas or urban slum upgrading projects, are constructed incrementally. Residents modify the interiors, exteriors, or openings of their homes based on their preferences, needs, and financial capabilities. However, securing openings or installing exhaust fans for ventilation does not appear to be a commonly considered option.

To improve the current situation, it is important to provide not only financial support but also knowledge support. This includes sharing specific methods to enhance natural ventilation, such as determining the size and position of openings, designing layouts, and other techniques with community members and small local construction businesses involved in the building process.

4. Conclusions

HBEs are prevalent in urban informal settlements and play a crucial role in the economies of low-income households across many developing countries. Such settings often suffer from poor infrastructure and substandard living conditions, rendering them susceptible to environmental stressors, including high temperatures and indoor air pollution. Our study employed a multimodal approach, incorporating field measurements, architectural observations, and interviews within twelve dwellings in Surakarta City, Indonesia. We aimed to explore the current conditions and challenges faced by individuals operating HBEs, with a specific focus on achieving thermal comfort indoors. Additionally, we thoroughly investigated common architectural design issues through our field surveys. Key findings from this study include the following:

- Thermal measurements inside six dwellings revealed temperatures exceeding 30 °C for 50–60% of working hours. This indicates a breach of acceptable thermal comfort standards and highlights the necessity for improvement in working conditions.

- Due to limited available land, the floor area per occupant varied between 8.6 and 13 m2 in most of the dwellings studied. Additionally, most dwellings shared two or three exterior walls with adjacent buildings. These densely populated conditions resulted in limited openings and significantly hampered cross-ventilation. Nine surveyed homes even had bedrooms without windows.

- Certain types of HBE activities, notably ironing and cooking, generated significant heat and water vapor indoors over extended periods. Despite this, none of the homes featured mechanical ventilation systems; reliance was solely on natural ventilation through open windows and doors.

- To maximize comfort under severe constraints, residents typically opened windows and doors to introduce outside air and conducted HBE activities in larger spaces with multiple openings. Despite these routine habits, there is a lack of effective building design to ensure cross-ventilation. In the surveyed dwellings that were incrementally modified, creating openings or installing exhaust fans for ventilation does not seem to be a commonly considered option.

Overall, this research has illuminated the pressing issue of hot and inadequate working conditions for HBE workers living in low-cost dwellings in Surakarta City, Indonesia. The findings underscore the urgent need for better architectural strategies and facilities that are applicable for both urban slum upgrading projects and the incremental construction of existing slum housing. By addressing these thermal comfort challenges, our research supports the achievement of sustainable development goals, particularly those related to health, well-being, and sustainable cities and communities (SDG 3, 11, and 13). Although there are challenges posed by economic constraints, the following actions are specifically recommended:

- In the context of urban slum upgrading projects, it is imperative to ensure cross-ventilation. This can be achieved by designing layouts where at least two sides of each building do not share walls with adjacent structures, thereby incorporating openings that face the external environment.

- It is essential to enhance the understanding of both residents and local construction workers regarding the importance of installing windows in appropriate positions and sizes. This knowledge can then be applied in the incremental renovation practices within the urban informal settlements and upgraded ones. To achieve this, advice and enlightenment from experts such as scholars and architects for the communities would be effective.

Our study offers valuable insights. However, the relatively small sample size could limit the robustness of our conclusions. Additionally, the study is geographically confined to Surakarta City and may not be directly applicable to other cities in Indonesia. In light of these findings, future research should explore the following points:

- Ventilation-related design parameters: Incrementally constructed low-cost dwellings are highly diverse, with numerous design variables affecting the indoor thermal environment. Future studies should focus on cross-ventilation factors, such as windowless rooms. Conducting field surveys on a larger number of samples will clarify the background and influencing factors that lead to flawed designs.

- Design guidelines development: For urban slum upgrading projects, it is crucial to develop design guidelines for low-rise housing. Recent studies have optimized building passive design for indoor thermal comfort and energy savings using surrogate-assisted models under various contexts [50]. Research using these methods will be advantageous in exploring appropriate designs that consider ventilation, lighting, and functionality within economic and land constraints.

- Surveying strategies: In urban slum upgrading projects across various Indonesian cities, particularly for constructing low-rise housing, it is important to survey the strategies employed by relevant sectors at all stages of planning, design, construction, and renovations by residents. These surveys will help identify ways to convey academic knowledge to stakeholders, ensuring better housing designs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation K.N.H. and A.H.; Methodology, K.N.H.; formal analysis K.N.H. and A.H.; investigation, K.N.H. and S.M.; data curation K.N.H., S.M. and A.T.W.; writing—original draft preparation, K.N.H.; writing—review and editing, A.H.; visualitation, K.N.H. and S.M.; supervision, A.H.; funding acquisition, K.N.H. and A.T.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was partially funded by MEXT KAKENHI grant number JP22 H01652, Sumitomo Foundation 2021 and DIKTI 2022, Ministry of Research, Technology and Higher Education of the Republic of Indonesia Scheme of Basic Research of Higher Education Excellence (Penelitian Dasar Unggulan Perguruan Tinggi—PDUPT).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the support and assistance with the field surveys and measurements to the students: Ulfa Adesti, Grace Angelica Nadapdap, Azkaluthfi Mahia Alif et al. and staff of the Urban–Rural Design and Conservation Laboratory, Department of Architecture, Universitas Sebelas Maret, Surakarta, Indonesia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

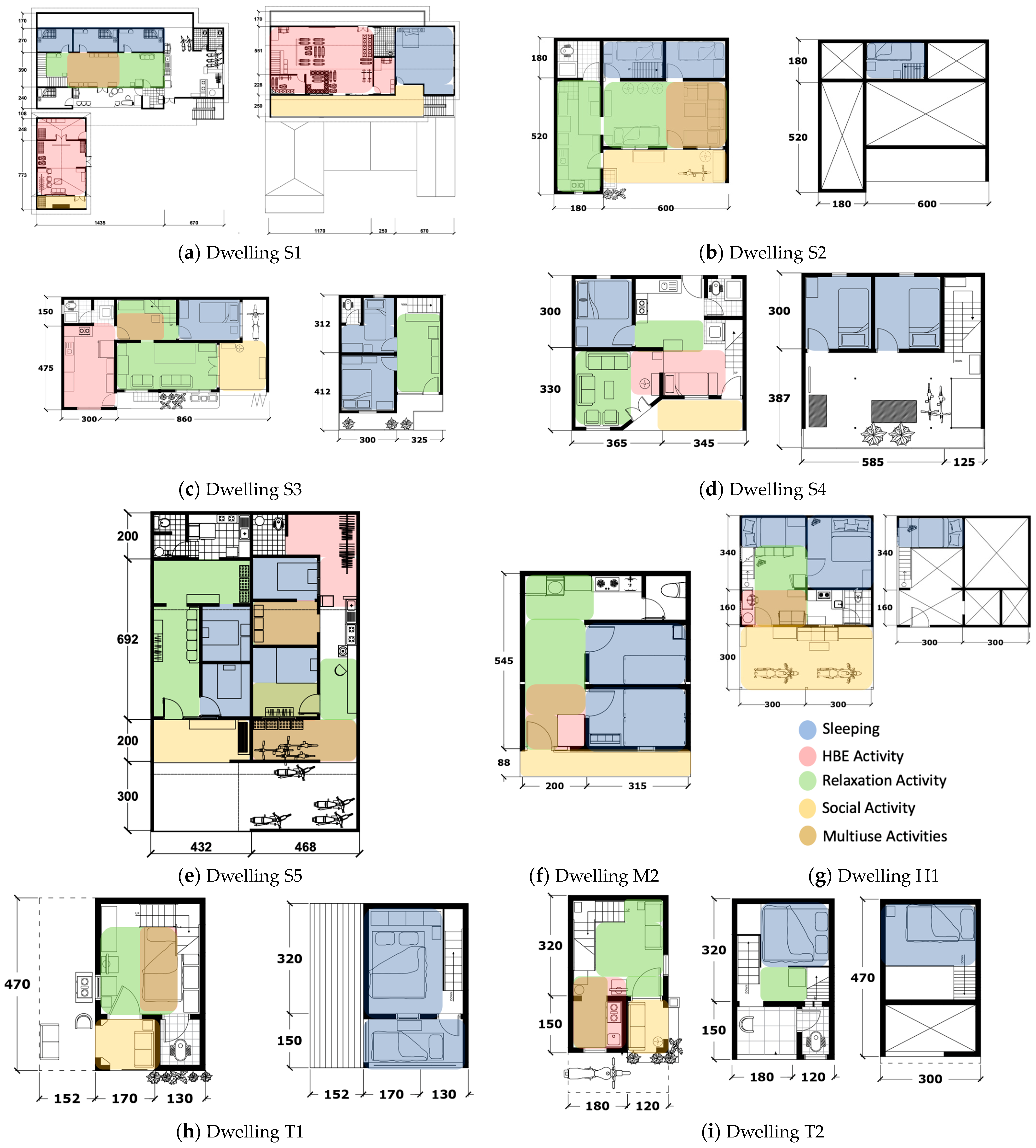

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Floor plans of surveyed dwellings including space use (unit: cm).

Figure A1.

Floor plans of surveyed dwellings including space use (unit: cm).

References

- Lee, H.; Calvin, K.; Dasgupta, D.; Krinner, G.; Mukherji, A.; Thorne, P.; Trisos, C.; Romero, J.; Aldunce, P.; Barrett, K.; et al. IPCC, 2023: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Core Writing Team, Lee, H., Romero, J., Eds.; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC): Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, J.J.; Saha, S.; Luber, G. Summertime Acute Heat Illness in U.S. Emergency Departments from 2006 through 2010: Analysis of a Nationally Representative Sample. Environ. Health Perspect. 2014, 122, 1209–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajat, S.; O’Connor, M.; Kosatsky, T. Health effects of hot weather: From awareness of risk factors to effective health protection. Lancet 2010, 375, 856–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toosty, N.T.; Hagishima, A.; Tanaka, K.I. Heat health risk assessment analysing heatstroke patients in Fukuoka City, Japan. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0253011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attia, S.; Benzidane, C.; Rahif, R.; Amaripadath, D.; Hamdy, M.; Holzer, P.; Koch, A.; Maas, A.; Moosberger, S.; Petersen, S.; et al. Overheating calculation methods, criteria, and indicators in European regulation for residential buildings. Energy Build. 2023, 292, 113170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climate Change in South East Asia. Output From GCM. Available online: https://www.env.go.jp/content/900448012.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- Jung, Y.T.; Hum, R.J.; Lou, W.; Cheng, Y.L. Effects of neighbourhood and household sanitation conditions on diarrhea morbidity: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0173808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtyas, S.; Toosty, N.T.; Hagishima, A.; Kusumaningdyah, N.H. Relation between occupants’ health problems, demographic and indoor environment subjective evaluations: A cross-sectional questionnaire survey study in Java Island, Indonesia. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0254460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubota, T.; Chyee, D.T.H.; Ahmad, S. The effects of night ventilation technique on indoor thermal environment for residential buildings in hot-humid climate of Malaysia. Energy Build. 2009, 41, 829–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toe, D.; Kubota, T. Field Measurement on thermal comfort in traditional Malay houses. Aij J. Technol. Des. 2013, 19, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djamila, H.; Chu, C.-M.; Kumaresan, S. Field study of thermal comfort in residential buildings in the equatorial hot-humid climate of Malaysia. Build. Environ. 2013, 62, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irakoze, A.; Lee, K.; Kim, K.H. Holistic Approach towards a Sustainable Urban Renewal: Thermal Comfort Perspective of Urban Housing in Kigali, Rwanda. Buildings 2023, 13, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naicker, N.; Teare, J.; Balakrishna, Y.; Wright, C.Y.; Mathee, A. Indoor Temperatures in Low Cost Housing in Johannesburg, South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WRI Indonesia. Seizing Indonesia Urban Opportunity: Compact, Connected, Clean and Resilient Cities as Drivers of Sustainable Development; WRI Indonesia: Jakarta Selatan, Indonesia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- UN Habitat. World Cities Report 2022; UN-Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2022; Available online: https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2022/06/wcr_2022 (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- Badan Pusat Statistik Kota Surakarta. Surakarta Municipality in Figure 2024. Vol. 48. Available online: https://surakartakota.bps.go.id/publication/2024/02/28/349be2091435020bbd015a7a/kota-surakarta-dalam-angka-2024.html (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- Obemeyer, C. Sustainable City Management—Informal Settlements in Surakarta, Indonesia; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Available online: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-319-49418-0 (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- Murtyas, S.; Hagishima, A.; Kusumaningdyah, N.H. On-site measurement and evaluations of indoor thermal environment in low-cost dwellings of urban Kampung district. Build. Environ. 2020, 184, 107239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtyas, S.; Minami, Y.; Handayani, K.N.; Hagishima, A. Assessment of Mould Risk in Low-Cost Residential Buildings in Urban Slum Districts of Surakarta City, Indonesia. Buildings 2023, 13, 1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrandt, S.; Kubota, T.; Sani, H.A.; Surahman, U. Indoor Air Quality and Health in Newly Constructed Apartments in Developing Countries: A Case Study of Surabaya, Indonesia. Atmosphere 2019, 10, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sani, H.; Kubota, T.; Sumi, J.; Surahman, U. Impacts of Air Pollution and Dampness on Occupant Respiratory Health in Unplanned Houses: A Case Study of Bandung, Indonesia. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prihardanu, E.G.; Kusnoputranto, H.; Herdiansyah, H. Indoor air quality in urban residential: Current status, regulation and future research for Indonesia. Int. J. Public Health Sci. (IJPHS) 2021, 10, 824–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.A. Informal Economy Monitoring Study Sector Report: Home-Based Workers; Women in Informal Employment Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO): Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.A.; Sinha, S. Home-based workers and cities. Environ. Urban. 2016, 28, 343–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassler, M. Home-working in Rural Bali: The Organization of Production and Labor Relations. Prof. Geogr. 2005, 57, 530–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikary, D.M.; Hajra, C. Health Expenditure of Home Based Worker & Access to Usable Water & Sanitation: A Case Study of Bidi workers in Purulia of West Bengal. Saudi J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2016, 1, 160–171. [Google Scholar]

- McCann, M. Hazards in cottage industries in developing countries. Am. J. Ind. Med. 1996, 30, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tipple, G. Employment and work conditions in home-based enterprises in four developing countries: Do they constitute ‘decent work’? Work Employ. Soc. 2006, 20, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tipple, G. The Place of Home-based Enterprises in the Informal Sector: Evidence from Cochabamba, New Delhi, Surabaya and Pretoria. Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 611–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamal, A.; Rohmah, L.; Muhyi, M.M. Housing preference shifting during COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia. J. Urban Manag. 2023, 12, 268–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumaningdyah, N.H. Features and Issues of Urban Industrial Batik Cluster Development in Surakarta and Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Trans. AIJ 2013, 78, 837–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawanson, T.; Olanrewaju, D. The Home as Workplace: Investigating Home Based Enterprises in Low Income Settlements of the Lagos Metropolis. Ethiop. J. Environ. Stud. Manag. 2012, 5, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezeadichie, N. Home-Based Enterprises in Urban Spaces: An Obligation for Strategic Planning? Berkeley Plan. J. 2012, 25, 44–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagemann, E.; Maynard, V.; Simons, B. Housing and home-based work: Considerations for development and humanitarian contexts. Cities 2024, 147, 104833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumaningdyah, N.H.; Sakai, T.; Deguchi, A.; Divigalpitiya, P. The Impact of Home-based Enterprises to Kampung Settlement Case Study of Serengan District, Surakarta. In Proceedings of the 8th International Symposium on City Planning and Environmental Management in Asian Countries. Asian Urban Research Group, Tianjin, China, 13–16 March 2012; pp. 297–310, ISBN 4-9980612-8-1. [Google Scholar]

- Sihombing, A.; Rahardja, A.A.; Gabe, R.T. The Role of Millennial Urban Lifestyles in the Transformation of Kampung Kota in Indonesia. Environ. Urban. ASIA 2020, 11, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumaningdyah, N.H.; Sakai, T.; Deguchi, A.; Divigalpitiya, P. The Productive Space of Kampung Kota Settlement: A Case Study Semanggi District, Surakarta—Indonesia. In Proceedings of the International Exchange and Innovation Conference on Engineering & Sciences (IEICES), Fukuoka, Japan, 18–19 October 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakoso, S.; Sudradjat, J.D. Spatial Characteristics of Home as Workplace: Investigation of Home-Based Enterprise in Several Housing Typologies in Indonesia. Built Environ. 2023, 49, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suparwoko; Raharjo, W. Home-based Enterprises in the International Kampong of Sosrowijayan: Housing Typology and Hybrid Cultural Approach to Tourism Development. In Proceedings of the EduARCHsia & Senvar 2019 International Conference (EduARCHsia 2019), Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 25–26 September 2019; Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putri, F.E.; Adianto, J.; Gabe, R.T. Double layered home-based enterprises: Case study in Kampung Lio, Depok. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 620, 012002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gierlang, B.P.; Ju, S.R.; Woerjantari, S. Housing Activities in Contemporary Indonesian Dwellings. J. Korean Hous. Assoc. 2016, 27, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EnergyPlus. Energy Plus: Energy Simulation Software. Available online: https://energyplus.net/ (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- Jani, D.B.; Bhabhor, K.; Dadi, M.; Doshi, S.; Jotaniya, P.V.; Ravat, H. A review on use of TRNSYS as simulation tool in performance prediction of desiccant cooling cycle. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2020, 140, 2011–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubota, T.; Zakaria, M.A.; Ahmad, M.H.; Toe, D.H.C. Energy-Saving Experimental House in Hot-Humid Climate of Malaysia. In Sustainable Houses and Living in the Hot-Humid Climates of Asia; Springer International Publishing: Singapore, 2018; Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-10-8465-2_43 (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- Tuck, N.W.; Zaki, S.A.; Hagishima, A.; Rijal, H.B.; Zakaria, M.A.; Yakub, F. Effectiveness of free running passive cooling strategies for indoor thermal environments: Example from a two-storey corner terrace house in Malaysia. Build. Environ. 2019, 160, 106214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Housing, Settlement, and Land Agency of Surakarta City. Development Plan Document and Development of Housing and Residential Areas (RP3KP) Surakarta City. Presented on the Forum Agency Performance Report, Surakarta, Indonesia, June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 55; Thermal Environmental Conditions for Human Occupancy. ASHRAE: Peachtree Corners, GA, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.ashrae.org/technical-resources/bookstore/standard-55-thermal-environmental-conditions-for-human-occupancy (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- Tutuko, P.; Shen, Z. Vernacular Pattern of House Development for Home based Enterprises in Malang, Indonesia. Int. Rev. Spat. Plan. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 2, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, R.U.; Garg, Y.K.; Bharat, A. A Framework for Evaluating Residential Built Environment Performance for Livability. Inst. Town Plan. India J. 2010, 7, 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, T.; Chakraborty, S.; Chowdhury, R. A Critical Review of Surrogate Assisted Robust Design Optimization. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2019, 26, 245–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).