Evaluation of Sustainable Tourism Development in Dachen Island, East China Sea: Stakeholders’ Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

Sustainable Tourism Development on Dachen Island

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Stakeholder Theory

2.2. Metrics of Sustainable Tourism and Stakeholders’ Interest

2.3. Conflicts of Interest among Stakeholders

2.4. Mechanisms of Resolving Conflicts of Interest among Stakeholders

3. Materials and Methods

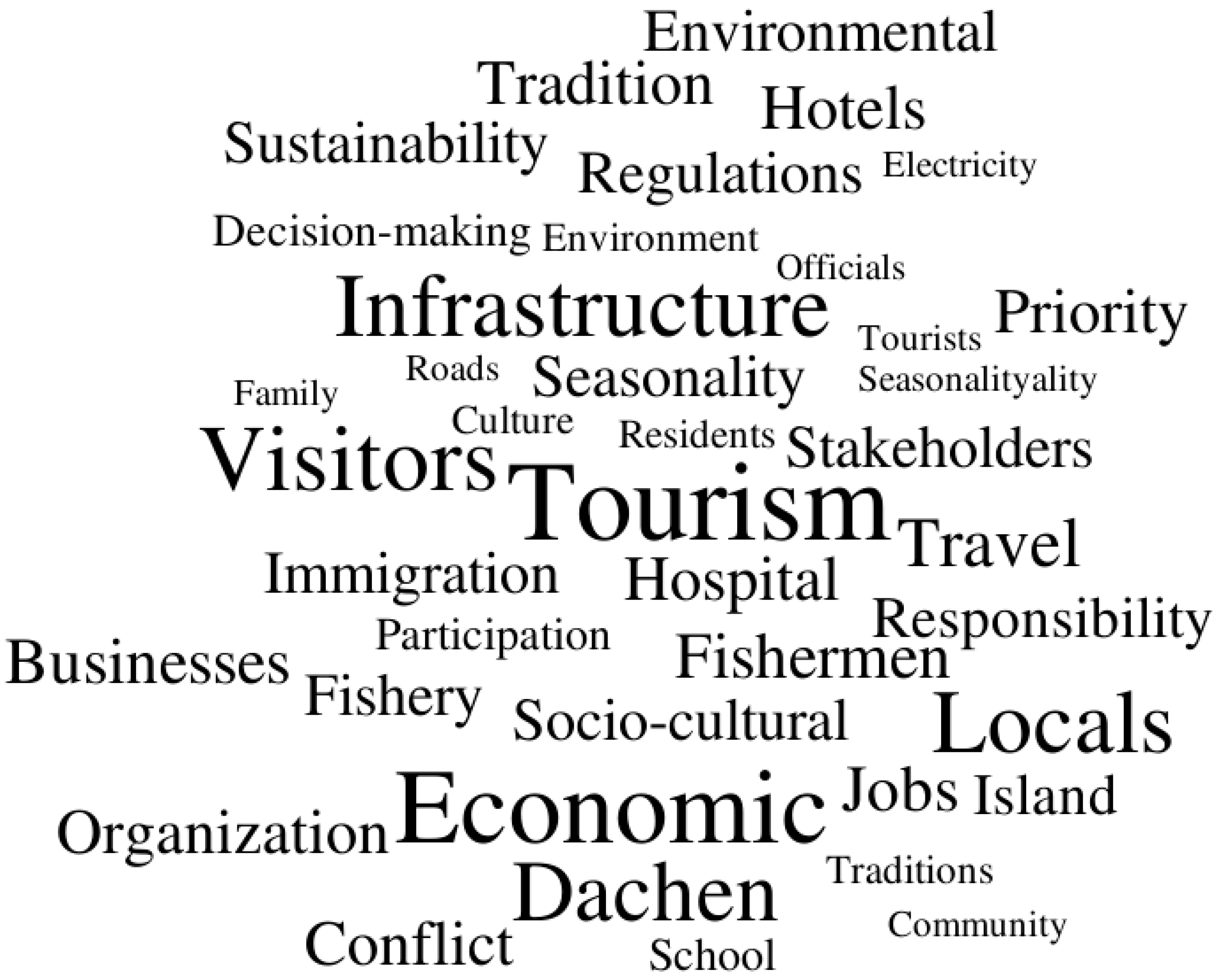

3.1. Initial Stage of Data Collection

3.2. Second Stage of Data Collection

4. Results

4.1. Stakeholders’ Perceived Assessment of Sustainable Tourism Development

4.2. Reasons for Conflict among Stakeholders

4.3. Proposed Mechanisms for Conflict Resolution

5. Discussion

6. Implications

7. Conclusions, Limitations, and Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Interview Questions

| Questions | Theoretical Support |

| General Questions (directed to all respondents) 1. What does the word sustainability mean to you? 2. What would it mean to achieve sustainability in Dachen Island? 3. What do you understand “sustainable tourism” to be? | Burbano et al. [37], Björk [23] |

| 4. What actions have been taken in the last 10 years to achieve sustainable tourism in Dachen Island? In light of these five metrics, please identify the sustainable tourism accomplishments in the last decade in terms of the five major metrics for sustainable tourism: | |

| (a) Environmental sustainability | Fernandez-Abila et al. [4]. Cohen [8] Burbano et al. [37] |

| (b) Economic sustainability | Burbano et al. [37] Krajnović et al. [2]. Hall’s [74] Rotarou [73] |

| (c) Socio-cultural Sustainability | Björk [23], Brown and Cave [10] |

| (d) Tourism development | Sun et al. [82,83], Walker et al. [87] |

| (e) Tourism management | Lim and Cooper [11], Higgins-Desbiolles et al. [69] Graci and Van Vliet [7] |

| 5. Are you satisfied with the sustainable tourism development efforts devoted in the last 10 years? Why or why not? | Walker et al. [87], Higgins-Desbiolles et al. [69] |

| 6. How can the tourism sector improve its management to promote sustainable tourism in Dachen Island? | Özgit [43], Tölkes [44] |

| 7. Based on your evaluation of sustainable tourism development in Dachen Island, Is there a conflict of interest among stakeholders in the Island (e.g., locals, visitors, hotels, small businesses, fishermen, and officials)? If yes, please explain how. | McComb [48], Salman [35,36,53], Murphy’s [54] |

| 8. What are the effective mechanisms for resolving conflict of interest among stakeholders and enhancing sustainable tourism development in the Island? Please suggest at least one mechanism. | Baloch et al. [71], Wu et al. [61] Koiwanit [65] Roxas et al. [66], Björ [23] and Angelkova et al. [24], Pasape et al. [57] |

| Specific Questions A. Questions for Academicians 1. Are the locals and visitors ready to accept and adapt to governmental sustainable tourism policies? How? 2. Why do some locals prefer to migrate to other cities in Zhejiang and other provinces? 3. What further actions should be done to enhance the sustainable tourism development in the Island? | Wu et al. [61], Roxas et al. [66], Graci and Van Vliet [7] |

| B. Questions for Locals 1. Why do some locals prefer to migrate to other cities in Zhejiang and other provinces? 2. Are locals ready to accept sustainable tourism policies (limited fishing, reserving nature etc.), and social and cultural sustainability (dealing with visitors from other cities)? 3. Does local government (in Dachen or Taizhou) communicate with key individuals on the Island? 4. Do local people have businesses such as cafes, restaurants, and convenience stores? 5. Is there a conflict of interest between the government’s sustainable development goals in Dachen Island and locals’ demands? Why? | Hardy and Pearson [9] and Waligo et al. [9,32] |

| C. Questions for Officials 1. Approximately, how many people live in Dachen Island? How many hotels? Hospitals? Schools? Community center? 2. Is Dachen Island highly populated especially when many people go to visit it? 3. Besides fishing activities, do local people have jobs in other organizations such as hotels and harbors? 4. Do visitors go to Dachen Island throughout the year or only in some seasons? | Mathew and Sreejesh [67], Moscardo and Murphy [54], Hardy and Pearson [9]. |

| D. Questions for Hotels’ Managers in Dachen Island 1. Are you satisfied with local authorities’ policies and actions in Dachen Island? 2. Are you satisfied with the infrastructure, services, and employment status in Dachen Island? 3. What exactly can you recommend for sustainable tourism in Dachen Island? | Hardy and Pearson [9], Pasape et al. [57] |

| E. Specific Questions for Visitors in Dachen Island 1. How often do you visit Dachen Island? Why? 2. Would you recommend others to visit it? 3. Are you satisfied with the Island’s infrastructure, services, and prices? | Mathew and Sreejesh [67], Lalicic [79] |

References

- Ke, W.; Guangdi, B. Diversified Tourism Products Stimulate New Demands in China. Available online: http://en.people.cn/n3/2023/0318/c90000-10224280.html (accessed on 8 January 2024).

- Krajnović, A.; Zdrilić, I.; Miletić, N. Sustainable Development of an Island Tourist Destination: Example of the Island of Pag. Acad. Tur.-Tour. Innov. J. 2021, 14, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggieri, G.; Calò, P. Tourism Dynamics and Sustainability: A Comparative Analysis between Mediterranean Islands—Evidence for Post-COVID-19 Strategies. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Abila, C.J.; Tan, R.; Dumpit, D.Z.; Gelvezon, R.P.; Hall, R.A.; Lizada, J.; Monteclaro, H.; Ricopuerto, J.; Salvador-Amores, A. Characterizing the sustainable tourism development of small islands in the Visayas, Philippines. Land Use Policy 2024, 137, 106996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecuyer, L.; White, R.M.; Schmook, B.; Calmé, S. Building on common ground to address biodiversity conflicts and foster collaboration in environmental management. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 220, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, T.; Shaw, D.; Kenawy, E. Examining the extent to which stakeholder collaboration during ecotourism planning processes could be applied within an Egyptian context. Land Use Policy 2018, 78, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia Ferrari, S.; Bain, A.A.; Crane De Narváez, S. Drivers, Opportunities, and Challenges for Integrated Resource Co-management and Sustainable Development in Galapagos. Front. Sustain. Cities 2021, 3, 666559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. Towards a convergence of tourism studies and island studies. Acta Tur. 2017, 29, 7–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hardy, A.; Pearson, L.J. Examining stakeholder group specificity: An innovative sustainable tourism approach. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 8, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.G.; Cave, J. Island tourism: Marketing culture and heritage—Editorial introduction to the special issue. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2010, 4, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.C.; Cooper, C. Beyond sustainability: Optimising island tourism development. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2009, 11, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, X. Green Energy Powers Development of East China Islands. Available online: http://ningbo.chinadaily.com.cn/2022-09/07/c_810271.htm (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Xu, L. Local Flavor Adds Spice to Tourism. Available online: www.chinadaily.com.cn (accessed on 13 February 2023).

- ChinaDaily.com. As Islands Go Electric, Emissions Decrease. Available online: https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202209/15/WS6322ce3fa310fd2b29e77d70.html (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Aria, M.; D’Aniello, L.; Della Corte, V.; Pagliara, F. Balancing tourism and conservation: Analysing the sustainability of tourism in the city of Naples through citizen perspectives. Qual. Quant. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Z.; Cheng, X. Fishery Resources, Ecological Environment Carrying Capacity Evaluation and Coupling Coordination Analysis: The Case of the Dachen Islands, East China Sea. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 876284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Q. Power Supplier Ensures Successful Energy Security in Zhejiang. Available online: https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202401/08/WS659be928a3105f21a507b27d.html (accessed on 11 January 2024).

- Gursoy, D.; Boğan, E.; Dedeoğlu, B.B.; Çalışkan, C. Residents’ perceptions of hotels’ corporate social responsibility initiatives and its impact on residents’ sentiments to community and support for additional tourism development. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2019, 39, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svendsen, A.C.; Laberge, M. Convening Stakeholder Networks. J. Corp. Citizsh. 2005, 2005, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Taheri, B.; Gannon, M.; Vafaei-Zadeh, A.; Hanifah, H. Does living in the vicinity of heritage tourism sites influence residents’ perceptions and attitudes? J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1295–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, E.T. Stakeholders in sustainable tourism development and their roles: Applying stakeholder theory to sustainable tourism development. Tour. Rev. 2007, 62, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, T.; Preston, L.E. The Stakeholder Theory of the Corporation: Concepts, Evidence, and Implications. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björk, P. Ecotourism from a conceptual perspective, an extended definition of a unique tourism form. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2000, 2, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelkova, T.; Koteski, C.; Jakovlev, Z.; Mitrevska, E. Sustainability and Competitiveness of Tourism. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 44, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Céspedes-Lorente, J.; Burgos-Jiménez, J.D.; Álvarez-Gil, M.J. Stakeholders’ environmental influence. An empirical analysis in the Spanish hotel industry. Scand. J. Manag. 2003, 19, 333–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, L.R.; Ritchie, J.R.B. Destination Stakeholders Exploring Identity and Salience. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 711–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D. Stakeholder involvement in sustainable tourism: Balancing the voices. In Global Tourism; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 230–247. [Google Scholar]

- Backman, K.F.; Munanura, I. Introduction to the special issues on ecotourism in Africa over the past 30 years. J. Ecotourism 2015, 14, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, A.; Hunter-Jones, P.; Warnaby, G. Are we any closer to sustainable development? Listening to active stakeholder discourses of tourism development in the Waterberg Biosphere Reserve, South Africa. Tour. Manag. 2017, 61, 234–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E.E.; McVea, J. A Stakeholder Approach to Strategic Management. SSRN Electron. J. 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenawy, E.; Osman, T.; Alshamndy, A. What Are the Main Challenges Impeding Implementation of the Spatial Plans in Egypt Using Ecotourism Development as an Example? Soc. Sci. 2017, 6, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waligo, V.M.; Clarke, J.; Hawkins, R. Implementing sustainable tourism: A multi-stakeholder involvement management framework. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 342–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riahi, Y. Project stakeholders:Analysis and Management Processes. Int. J. Econ. Manag. Stud. 2017, 4, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidmamatov, O.; Matyakubov, U.; Rudenko, I.; Filimonau, V.; Day, J.; Luthe, T. Employing Ecotourism Opportunities for Sustainability in the Aral Sea Region: Prospects and Challenges. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, A.; Jaafar, M.; Mohamad, D. Understanding the Importance of Stakeholder Management in Achieving Sustainable Ecotourism. Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2021, 29, 731–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, A.; Jaafar, M.; Mohamad, D.; Malik, S. Ecotourism development in Penang Hill: A multi-stakeholder perspective towards achieving environmental sustainability. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 42945–42958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burbano, D.V.; Valdivieso, J.C.; Izurieta, J.C.; Meredith, T.C.; Ferri, D.Q. “Rethink and reset” tourism in the Galapagos Islands: Stakeholders’ views on the sustainability of tourism development. Ann. Tour. Res. Empir. Insights 2022, 3, 100057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajablu, M.; Marthandan, G.; Yusoff, W.F.W. Managing for Stakeholders: The Role of Stakeholder-Based Management in Project Success. Asian Soc. Sci. 2014, 11, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dornier, R.; Mauri, C. Overview: Tourism sustainability in the Alpine region: The major trends and challenges. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2018, 10, 136–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-H.; Kim, S.-H.; Kwon, H.-S. Mapping Interests by Stakeholders’ Subjectivities toward Ecotourism Resources: The Case of Seocheon-Gun, Korea. Sustainability 2017, 9, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R. Sustainable Tourism in Sensitive Environments: A Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing? Sustainability 2018, 10, 1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, T.J.; Moldoveanu, M. When Will Stakeholder Groups Act? An Interest- and Identity-Based Model of Stakeholder Group Mobilization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2003, 28, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özgit, H. How should small island developing states approach long-term sustainable development solutions? A thematic literature review. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2022, 14, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tölkes, C. Sustainability communication in tourism—A literature review. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 27, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M. Constructing sustainable tourism development: The 2030 agenda and the managerial ecology of sustainable tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1044–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, B.; Higham, J.; Lane, B.; Miller, G. Twenty-five years of sustainable tourism and the Journal of Sustainable Tourism: Looking back and moving forward. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.; Chatterjee, B. Ecotourism: A panacea or a predicament? Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2015, 14, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H. Managing conflict by mapping stakeholders’ views on ecotourism development using statement and place Q methodology. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2022, 37, 100453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihalic, T. Conceptualising overtourism: A sustainability approach. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 84, 103025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McComb, E.J.; Boyd, S.; Boluk, K. Stakeholder collaboration: A means to the success of rural tourism destinations? A critical evaluation of the existence of stakeholder collaboration within the Mournes, Northern Ireland. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2017, 17, 286–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihalic, T. Sustainable-responsible tourism discourse—Towards ‘responsustable’ tourism. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 111, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berardi, U. Stakeholders’ influence on the adoption of energy-saving technologies in Italian homes. Energy Policy 2013, 60, 520–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, A.; Jaafar, M.; Mohamad, D. Strengthening Sustainability: A Thematic Synthesis of Globally Published Ecotourism Frameworks. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2020, 9, 246–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, P. Tourism: A Community Approach (RLE Tourism); Routledge: London, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Salman, A.; Jaafar, M.; Mohamad, D.; Khoshkam, M. Understanding Multi-stakeholder Complexity & Developing a Causal Recipe (fsQCA) for achieving Sustainable Ecotourism. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 25, 10261–10284. [Google Scholar]

- Cobbinah, P.B.; Black, R.; Thwaites, R. Ecotourism implementation in the Kakum Conservation Area, Ghana: Administrative framework and local community experiences. J. Ecotourism 2015, 14, 223–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasape, L.; Anderson, W.; Lindi, G. Towards Sustainable Ecotourism through Stakeholder Collaborations in Tanzania. J. Tour. Res. Hosp. 2013, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wondirad, A.; Tolkach, D.; King, B. Stakeholder collaboration as a major factor for sustainable ecotourism development in developing countries. Tour. Manag. 2020, 78, 104024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobbinah, P.B.; Amenuvor, D.; Black, R.; Peprah, C. Ecotourism in the Kakum Conservation Area, Ghana: Local politics, practice and outcome. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2017, 20, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Yang, R.R. A Research on Eco-Tourism Development Models Based on the Stakeholder Theory. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2013, 291–294, 1447–1450. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Lai, I.K.W.; Tang, H. Evaluating the Sustainability Issues in Tourism Development: An Adverse-Impact and Serious-Level Analysis. Sage Open 2021, 11, 215824402110503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yolal, M.; Gursoy, D.; Uysal, M.; Kim, H.; Karacaoğlu, S. Impacts of festivals and events on residents’ well-being. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 61, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasso, A.; Dahles, H. Are tourism livelihoods sustainable? Tourism development and economic transformation on Komodo Island, Indonesia. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 23, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.; Twining-Ward, L. Monitoring for a Sustainable Tourism Transition: The Challenge of Developing and Using Indicators; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Koiwanit, J.; Filimonau, V. Stakeholder collaboration for solid waste management in a small tourism island. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0288839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roxas, F.M.Y.; Rivera, J.P.R.; Gutierrez, E.L.M. Mapping stakeholders’ roles in governing sustainable tourism destinations. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 45, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, P.V.; Sreejesh, S. Impact of responsible tourism on destination sustainability and quality of life of community in tourism destinations. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2017, 31, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscardo, G.; Murphy, L. There Is No Such Thing as Sustainable Tourism: Re-Conceptualizing Tourism as a Tool for Sustainability. Sustainability 2014, 6, 2538–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F.; Carnicelli, S.; Krolikowski, C.; Wijesinghe, G.; Boluk, K. Degrowing tourism: Rethinking tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1926–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecot, M.; Ricaurte-Quijano, C. ‘¿Todos a Galápagos?’ Overtourism in wilderness areas of the Global South. In Overtourism: Excesses, Discontents and Measures in Travel and Tourism; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2019; pp. 70–85. [Google Scholar]

- Baloch, Q.B.; Shah, S.N.; Maher, S.; Irshad, M.; Khan, A.U.; Kiran, S.; Shah, S.S.; Crociata, A. Determinants of evolving responsible tourism behavior: Evidences from supply chain. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2022, 8, 2099565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Ismail, H.N.; Yee, T.P.; Li, F. Exploring the effect of destination social responsibility on responsible tourist behavior: Symmetric and asymmetric analysis. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2024, 29, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, B.E.; Rotarou, E.S. Island Tourism-Based Sustainable Development at a Crossroads: Facing the Challenges of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M. Changing Paradigms and Global Change: From Sustainable to Steady-state Tourism. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2010, 35, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzitutti, F.; Walsh, S.J.; Rindfuss, R.R.; Gunter, R.; Quiroga, D.; Tippett, R.; Mena, C.F. Scenario planning for tourism management: A participatory and system dynamics model applied to the Galapagos Islands of Ecuador. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 1117–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, B. Participative Planning and Governance for Sustainable Tourism. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2010, 35, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscardo, G. Exploring social representations of tourism planning: Issues for governance. J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabphet, S.; Scott, N.; Ruhanen, L. Applying diffusion theory to destination stakeholder understanding of sustainable tourism development: A case from Thailand. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 1107–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalicic, L. Open innovation platforms in tourism: How do stakeholders engage and reach consensus? Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 2517–2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenawy, E.H.; Shaw, D. Developing a More Effective Regional Planning Framework in Egypt: The Case of Ecotourism; WIT press: Seville, Spain, 2014; pp. 77–91. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Hashemi, S.; Yao, Y.; Kiumarsi, S.; Liu, D.; Tang, J. How Do Tourism Stakeholders Support Sustainable Tourism Development: The Case of Iran. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.Y.; Lin, Z.W. Move fast, travel slow: The influence of high-speed rail on tourism in Taiwan. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 433–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, T.; Lee, T. Visitor and resident perceptions of the slow city movement: The case of Japan. Int. J. Tour. Sci. 2019, 19, 112–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tantalo, C.; Priem, R.L. Value creation through stakeholder synergy. Strateg. Manag. J. 2016, 37, 314–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, E.T.; Gustke, L. Using decision trees to identify tourism stakeholders. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2011, 4, 148–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. The Stakeholder Approach. In Strategic Management; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, T.B. A Review of Sustainability, Tourism, and the Marketing Opportunity for Adopting the Cittàslow Model in Pacific Small Islands. Tour. Rev. Int. 2020, 23, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Stakeholders | Number | Brief Description |

|---|---|---|

| Locals | 9 | 4 fishermen, 3 employees, and 2 retirees. |

| Small business owners | 4 | Owners of restaurants, convenience stores, cafes. |

| Visitors | 7 | 5 regular visitors and 2 visitors (first time). |

| Officials | 2 | Director of the publicity department of Dachen island, Chinese communist party member. |

| Hotel managers | 5 | Working at five big hotels for more than 7 years. |

| Academicians * | 2 | Two professors specialize in sustainable tourism development. |

| Dimensions | Description |

|---|---|

| Environmental | Implementation of numerous eco-friendly practices such as recycling initiatives, ensuring reasonable and responsible fishing activities, waste management programs. |

| Economic | Remarkable investment in infrastructure (especially wind power generation, roads and Island ports). Job creation, especially in the hospitality, fishery, and food and beverage industry. |

| Social-cultural | Community engagement to ensure the voices of the local community are heard and their interests are protected. Cultural preservation (support local artisans, celebrate island customs and history, showcasing traditional crafts). |

| Tourism development | Offering a diverse range of tourism experience such as eco-tours and cultural immersion programs. Encouraging visitors to be responsible by providing effective education and guidance on conservation efforts, and responsible tourism practices through interpretive guides and visitor centers. |

| Tourism management | Establishing a regulatory framework that includes zoning regulations, environmental impact assessments, and tourism guidelines to ensure responsible and sustainable development. Fostering stakeholder’s collaboration between locals, community centers, and local businesses. |

| Concern | Description |

|---|---|

| Economic Distribution and Community Benefits | Locals feel that they are not adequately benefiting from tourism-related income, employment opportunities, or business development. Concerns about leakage of tourism revenue to external entities, lack of local entrepreneurship, or insufficient investment in community development. |

| Locals vs. Tourist Interests | Locals have concerns about the negative impacts of tourism (e.g., rising cost of living, overcrowding, and changes to traditional lifestyle) on their access to resources, quality of life, and cultural heritage, while visitors look for amenities and attractions. |

| Tourism Seasonality | Tourist arrivals often fluctuate seasonally, leading to challenges in managing the impact on local communities and businesses. During peak seasons, tourism operators and some locals feel overwhelmed by crowds, while businesses struggle to meet demand during off-peak periods. |

| Traditional Culture and Tourism Adaptation | Locals emphasize the importance of preserving local traditions and authentic cultural experience. Visitors and tourism operators advocate the need to meet the expectations of tourists through commercialization and entertainment. |

| Environmental Conservation vs. Tourism Development | Locals advocate for strict environmental regulations and limitations on tourist activities to protect the ecosystems of Dachen Island. Officials, tourism operators, and visitors prioritize economic growth and job creation through increased tourism. |

| Tourism Infrastructure vs. Natural Landscape | Locals highlight the importance of preserving the landscape of Dachen Island while visitors and tourism operators advocate the importance of building hotels, resorts, and recreational facilities to enhance tourism development. Locals call for building new and renovating existing buildings such as hospitals, community centers, and schools. |

| Proposed Mechanism | Description |

|---|---|

| Involve Local Communities | Locals should have a voice and be actively involved in decision making, as they are directly affected by tourism activities. Encourage their participation in discussions, provide opportunities for input, and ensure their concerns are considered in decision-making processes. |

| Enhance Infrastructure and Services | Invest in infrastructure and services that benefit both visitors and locals. This may include improving transportation systems, waste management facilities, public spaces, and community facilities. |

| Encourage Responsible Visitor Behavior | Promote responsible tourism practices among visitors through education, awareness campaigns, and codes of conduct. Emphasize the importance of respecting local customs, minimizing environmental impact, supporting local businesses, and engaging in cultural exchange in a respectful manner. |

| Diversification of Tourism Offerings | Encourage diversification of tourism offerings to reduce pressure on popular attractions and distribute tourist spending more evenly across the island. Promote ecotourism, cultural tourism, and other sustainable tourism activities that showcase the island’s unique assets. |

| Education and Awareness | Increase awareness among tourists, locals, and businesses about the importance of sustainable tourism practices. Provide education on environmental conservation, cultural sensitivity, and responsible tourism behavior to promote mutual respect and understanding. |

| Stakeholder Engagement | Encourage meaningful participation and dialogue among locals, tourists, businesses, and community groups. Involve stakeholders in decision-making processes related to tourism development, ensuring that their concerns and perspectives are heard and considered. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ali, H.; Li, Y. Evaluation of Sustainable Tourism Development in Dachen Island, East China Sea: Stakeholders’ Perspective. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7206. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16167206

Ali H, Li Y. Evaluation of Sustainable Tourism Development in Dachen Island, East China Sea: Stakeholders’ Perspective. Sustainability. 2024; 16(16):7206. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16167206

Chicago/Turabian StyleAli, Hazem, and Yanchao Li. 2024. "Evaluation of Sustainable Tourism Development in Dachen Island, East China Sea: Stakeholders’ Perspective" Sustainability 16, no. 16: 7206. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16167206

APA StyleAli, H., & Li, Y. (2024). Evaluation of Sustainable Tourism Development in Dachen Island, East China Sea: Stakeholders’ Perspective. Sustainability, 16(16), 7206. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16167206