Abstract

The article concerns the issue of equal opportunities for disabled employees as sustainable participation in the labor market in selected workplaces in Poland. Disabled people are part of society; therefore, they should not be discriminated against by exclusion and allowed to participate fully in public life. This work analyzes scientific publications and fragments of reports, which have made it possible to draw conclusions on what areas of life disabled people have problems with regarding functioning and what should be changed to improve their quality of life. The aim of the article was to analyze examples of facilities used, among others, at universities that allow disabled people to move safety and freely. The substantive scope includes reference to Polish legal regulations regarding the process of employing disabled people in a balanced labor market against the background of statistical data. The article indicates that workplace facilities for disabled people (mobile and visually impaired) have a positive impact on the functioning of the rest of society due to the elimination of architectural barriers.

1. Introduction

In today’s society, more and more attention is paid to issues of sustainable development and equal opportunities for everyone [1,2,3]. In this context, it is crucial to consider the needs and limitations of disabled people in both social and professional life. This is not only a matter of legal requirements, but also an expression of concern and willingness to develop for every citizen, regardless of their physical or mental abilities. A very important factor is also the change in society’s thinking and attitude towards people with disabilities. Meanwhile, society’s failure to adapt persons with disabilities leads to a number of negative consequences, not only for the disabled themselves, but also for society as a whole. Harmful stereotypes and prejudices regarding disabled people result in, among others, social exclusion, deepening existing social inequalities (including education, work and recreation), intensifying difficulties in everyday functioning, causing low self-esteem of disabled people, and even causing economic losses (e.g., loss of potential income for persons with disabilities, but also loss of valuable capital human for society). Pessimistic views about these people’s ability to work have been published by authors [4,5,6,7]. At this point, every reader of this article should answer the following questions: If I come into contact with a disabled person, can I help him, support him, and make his functioning easier? Or maybe I look at them with contempt or try to ignore them and pretend they do not exist? If you answered yes to the second question, this article is for you. To sum up, it is necessary to urgently take extensive actions aimed at increasing accessibility to the requirements of people with disabilities, not only to public spaces (including public buildings and public transport), residential properties and services, but above all to places and workplaces. An interesting cross-land perspective can be found in the works [8,9,10,11].

This work attempts to explore issues related to the employment of disabled people in the workplace, in particular the adaptation of places and workstations for persons with disabilities, considering available technological solutions. The role of office space design, its impact on accessibility for people with disabilities, and best practices in creating professional space are also discussed. It is worth adding that Poland ratified the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in 2012.

The primary goal of the article is to present practical tips for employers on how to adapt the work environment to the needs of disabled employees to make it more open and inclusive. Moreover, it is intended to be a source of inspiration for the disabled themselves, showing them that there are opportunities to create equal opportunities and professional opportunities for them.

2. Disability Terminology

Due to the fact that disability is a very complex and multi-faceted concept, and therefore not understood by the majority of society, it is necessary to first point out the differences resulting from legal provisions and the incorrect perception of disabled people by society.

The definition of disability should be considered in various aspects: medical, legal, and social, as well as disability or inability to work. The meaning of each of these terms refers primarily to the fields that defined the term. Doctors and the medical community have a different view on disability, and sociologists and anthropologists have a different view. To sum up, although these definitions have a similar meaning, they differ in terms of applicable legal conditions, the development of medical research and changes that take place in a changing society.

According to the Act of 27 August 1997 [12], disability means a permanent or periodic inability to fulfill social roles due to a permanent or long-term impairment of the body’s fitness, in particular resulting in an inability to work.

The World Health Organization (WHO) [13] defines disability in three ways, considering the human health condition:

- -

- impairment in a person’s body structure or function, or mental functioning; examples of impairments include loss of a limb, loss of vision, or memory loss;

- -

- disability—activity limitation, such as difficulty seeing, hearing, walking, or problem solving;

- -

- handicap—participation restrictions in normal daily activities, such as working, engaging in social and recreational activities, and obtaining health care and preventive services.

The International Classification of Diseases (ICD) focuses on health problems such as diseases, disorders, and injuries. The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) is one of three components of the ‘WHO Family of International Classifications’. The ICF is a standard and universal language and conceptual basis to understand and describe disability. It brings together the diverse models of disability and understands disability as a description of the situation of a person rather than as a characteristic of the person. ICF is unique classification based on a holistic assessment of a patient [14,15]. The Convention on the Rights of Person with Disabilities includes the definition of person with disabilities as those who have long-term physical, mental, intellectual, or sensory impairments, which, in interaction with various barriers, may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others [16].

3. Employment of Disabled People in Poland—Statistics, Benefits

Therefore, is every person who has conditions qualifying him or her as a disabled person incapable of undertaking professional work? Well, no! The differences that define a given issue can be divided into four categories:

- -

- influence on areas of life,

- -

- conditioning premises,

- -

- social scope,

- -

- the case law (the case law on disability).

Analyzing the impact on areas of life, it can be concluded that disability affects many areas of a person’s life, while inability only affects a person’s ability to undertake professional work. The remaining categories can be described similarly, i.e., disability results from various causes, i.e., congenital defects, injuries, and acquired diseases, and thus affects the possibility of education, emotional, and social development, while inability to work results from limitations to undertake a given type of professional work. The last category is the difference in case law, which differs in that disability is determined by a commission composed of medical specialists, while incapacity for work is assessed by the institutions responsible for the social security system.

Disabled people can take up professional work; it is necessary to consider in which sectors of the economy they are most often employed. The answer to this question can be found in the reports of the Central Statistical Office, which presents them periodically on its website. Namely, the report on disabled people in 2021 clearly showed that the majority of disabled people worked in medium and large enterprises in the private sector, as many as 75.2% [17].

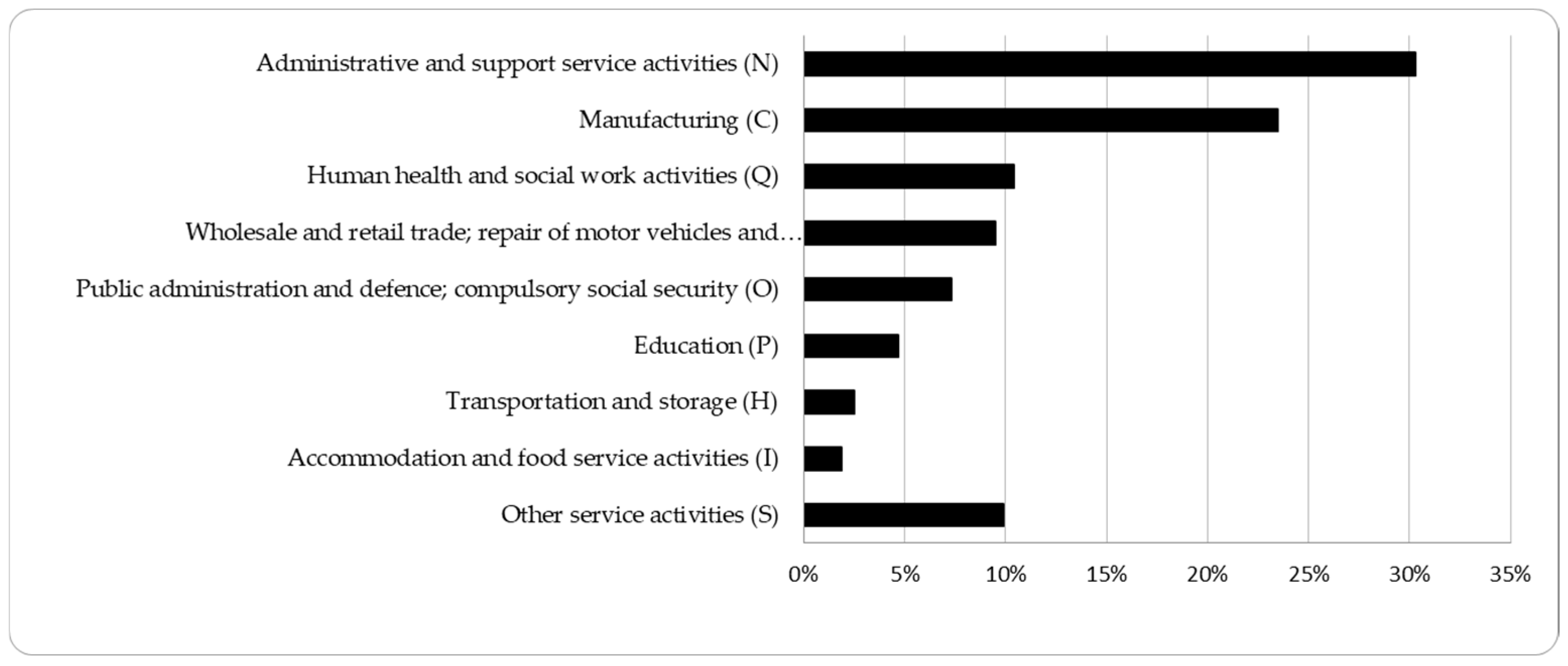

Analyzing the published statistics shown in Figure 1, it can be concluded that 30.3% of people employed were related to the administrative and services activities, which include detective activities (18.7%) and maintaining order in buildings and developing green areas (8.4%). Further groups of employees found employment in the industrial processing sectors (23.5%), and health care and social assistance (10.4%). The remaining sectors accounted for less than 10% of disabled people employed.

Figure 1.

Share of industry sectors employing disabled people in Poland. Source: own elaboration based on [17].

Referring to three distinctive industry sectors with which each of us has contact in everyday life, a list of requirements that a disabled person must meet to take up employment in a given industry has been prepared, as presented in Table 1. In addition, contraindications excluding employment and opportunities have been specified. adapting the position to a disabled person due to their dysfunction.

Table 1.

Characteristics of sample job positions.

Analyzing the issue of employment of disabled people in Poland, Table 2 presents the statistics of persons with disabilities by gender and age groups living in individual voivodeships in 2009 and 2014 [19]. Other issues of professional activation of disabled people in Poland are presented in the works [20,21,22].

Table 2.

Statistics of disabled people by voivodeships and age groups in 2009 and 2014.

The report clearly shows that among the population living in Poland in 2009, 13.9% of the population showed the characteristics of a disabled person. Similarly, in 2014, 12.9% had signs of disability, which means a decrease of 1 percentage point compared to 2009 [17].

As for the highest and lowest rates of disabled people living in individual voivodeships, the situation was as follows:

- -

- In 2009, the highest rate of disabled people was recorded in the Lubelskie Voivodeship (16.3%), while the lowest rate was recorded in the Świętokrzyskie Voivodeship (12.0%).

- -

- In 2014, the highest rate of disabled people was recorded in the Lubuskie Voivodeship (17.2%), while the lowest in the Mazowieckie Voivodeship (10.1%).

Analyzing these data, it is possible to state an increase in the number of people showing the characteristics of a disabled person by 0.9 percentage points, and at the same time, a decrease by 1.9 percentage points compared to the voivodeships with the highest and lowest rates in a given year.

Seemingly, the percentages presented in the report range from 10.1% to 17.2%, which may lead one to think that this is quite a low value. However, if we convert the percentages into the number of people, the situation looks worse. Namely, in a group of 10 random people, it can be assumed that 2 people have limitations that qualify them as a person with a disability.

Due to the fact that the Central Statistical Office changed the structure and method of presenting data in 2021, a comparative analysis of the results for 2019 was not possible in accordance with the previously adopted scheme. The discrepancies between the publication dates of the report and the data for a given year result from the fact that the Central Statistical Office, after collecting data for a given year, thoroughly analyzes the results obtained, which are probably mainly used for decision-making by authorized persons in the government, and then prepares a report on the health of the Polish population, which contains data, e.g., on the addictions of Polish women and men, and information on disabled people. Therefore, the report on, for example, data for 2009, was published only in 2011, while the data for 2014 was published in 2016. This shows that the data are collected cyclically and are published approximately every 2–3 years from the moment of receiving appropriate data for analysis.

Analyzing the above data, it can be concluded that the aging society and the progression of lifestyle diseases will result in the percentage of people with disabilities increasing, and each year, the financial needs of society and the state will increase to improve the living conditions as well as the urgent adaptation of public–private space and professional spaces to the requirements of people with disabilities.

It should be noted here that employing a disabled person is completely possible. However, this requires good will on the part of the employer, in the form of taking time to learn the requirements for a given type of disability, as well as the financial outlay that the employer incurs in order to adapt the workplace to the needs of a disabled person. However, it is worth knowing that an employer who employs disabled people beyond his duties can count on the support he is entitled to when employing disabled people. Namely, each establishment employing at least 25 full-time employees is obliged to pay contributions to the State Fund for the Rehabilitation of Disabled Persons PFRON [18].

The amount of the PFRON contribution is calculated based on the formula:

This is example 1 of an Equation (1):

where:

Kz = 40.65% × Pw × (Z0 × 6% − Zn)

Kz—the amount of the contribution to PFRON,

Pw—average salary in the previous quarter,

Z0—number of people employed full-time,

Zn—number of disabled people employed full-time

The greater the number of disabled people is employed, the lower the contribution amount is, and at the same time, the less burdensome it is for the workplace.

However, this is not the end of the benefits for the employer. Namely, if the employer employs at least 25 full-time employees and achieves an employment rate of at least 6%, he or she may count on exemption from the need to pay PFRON contributions [18].

This indicator can be calculated from the following Formula (2):

where:

W = ZON/ZOG

ZON—number of disabled people per full-time equivalent,

ZOG—total number of people employed on a full-time basis.

In addition to the possibility of exemption from the obligation to pay PFRON contributions, employers can count on co-financing of the employee’s remuneration depending on the degree of disability in the amount from PLN 500 in the case of a mild degree of disability to PLN 2400 in the case of a significant degree of disability.

These amounts can be increased from PLN 600 to PLN 1200 in the case of employing a person with a diagnosed mental illness, mental retardation or epilepsy.

In addition to the rights listed above, employers can count on:

- -

- reimbursement of the costs of employing a person supporting the work of a disabled person,

- -

- reimbursement of the costs of adapting the workplace in the amount of 20 times the salary of a disabled person,

- -

- reimbursement of workplace equipment costs in the amount of 15 times the salary.

To sum up, employing a disabled person is beneficial both for the employer, but above all for the disabled person, who can integrate into the professional environment, take part in the life of the company, and bring his or her own experience and often enormous amounts of energy and knowledge. In turn, from the employer’s perspective, he gains a committed and willing employee who can also reduce additional costs resulting from running a business in the form of necessary payments for PFRON contributions.

4. Methodology

The research methodology was based on a several-stage structure. The study used several research methods, i.e., a review of international and national literature, analysis of national statistical data on the professional activation of people with disabilities, exploratory analysis of a review of problems faced by people with disabilities, and the visualization of research results (case studies).

Leading a public life for people with disabilities who have to overcome many difficulties in everyday life, it is not so obvious. The highlighted problems that were identified in the research work include:

- -

- lack of accessibility to buildings and public places,

- -

- limiting the use of services and entertainment,

- -

- difficulty moving,

- -

- discrimination,

- -

- financial problems,

- -

- difficulties in obtaining employment.

The above-mentioned difficulties create a vicious circle in which one problem results from another and causes subsequent problems to pile up. And although someone might say that it is enough to solve one problem to help and improve the situation, in the case of disabled people, such thinking is wrong. For a disabled person, every activity and every change is associated with long-term planning of what his space should look like and how he should find his way in the changing conditions that surround him.

Thanks to the involvement of the state authorities of various countries associated with the United Nations (UN), on 13 December 2006, the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities was adopted, which aims to protect and ensure the full and equal enjoyment of human rights and fundamental freedoms by persons with disabilities on an equal basis. with all other citizens. The adoption of the convention was a clear signal of the necessary changes that must take place in society for the problems to be noticed by people without disabilities [23].

In the context of the needs of disabled people, the Polish State has also adopted appropriate resolutions, including [12], which defines the concept of a disabled person, types of degrees of disability, authorized bodies to adjudicate and grant the status of a disabled person, and in the context of employing disabled people, it indicates the obligations and rights of employers employing disabled people or the rights of disabled people, i.e., working time and amount of additional holiday leave.

The problems causing a chain reaction include the broadly understood lack of accessibility resulting from the lack of architectural adaptation of buildings and public places, which prevents disabled people from moving around in public space or participating in cultural events.

This problem was also discussed in [19], which analyzed the problems that disabled people have to face in their everyday lives. These include the following factors:

- -

- poorly designed public architecture—streets and sidewalks that make movement difficult,

- -

- public transport not adapted to the needs of disabled people—high steps, narrow entrances to vehicles, inability to enter a wheelchair,

- -

- insignificant number of amenities in public space—designing pedestrian crossings without amenities for blind and deaf people.

Although these problems seem trivial and insignificant for an able-bodied person who can cope with difficulties, for a disabled person, it is a reason that discourages them from participating in public life and is often a reason for withdrawing from public life and closing themselves in their comfort zone, which is most often their house or apartment. Thanks to the involvement of state authorities and specially appointed commissions or governmental and non-governmental institutions, an increased awareness of the needs of disabled people can be observed. The increasing number of legal regulations and requirements imposed on society in the context of designing newly constructed buildings and public places is a positive phenomenon that changes the space around us towards equal accessibility for able-bodied people and those with special needs. The amenities that must be met during the construction and modernization of buildings include:

- -

- ensuring an appropriate number of parking spaces and access to the building,

- -

- ensuring free movement inside the building for people with mobility limitations, as well as for people with visual or hearing impairments,

- -

- adapting hygiene rooms to the needs of disabled people in the form of an appropriate amount of space inside and auxiliary handles.

The above analysis of the problems allows us to conclude that changes should be introduced in small steps, starting from meeting the basic living needs of disabled people, i.e., access to residential buildings or public buildings, e.g., health clinics, hospitals, and then the secondary needs that are aimed at improving mobility or access to cultural buildings.

5. Data and Results—Examples of Selected Amenities in the Work/Study Place of Disabled People

The process of adapting public space to the needs of disabled people may seem complicated and difficult to understand. Is this really the case? The answer to this question will be presented in several examples presenting solutions that have been introduced in buildings used for the didactic education of students with disabilities and university students. One of the basic activities of every person’s day is the process of moving between different locations. Therefore, the space surrounding workplaces and public buildings should be best adapted to this activity. Therefore, the basic activity should be to designate a parking space for disabled people that will meet the appropriate requirements, i.e., adequate space for maneuvering and locating it near the entrance, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Parking spaces of the Wrocław University of Science and Technology (own study).

The next step is to reach the building where the workplace is located. Stairs often lead to such buildings, and next to them, there is a dedicated ramp for wheelchair users, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Driveway leading to the building of the University of Economics in Wrocław (own study).

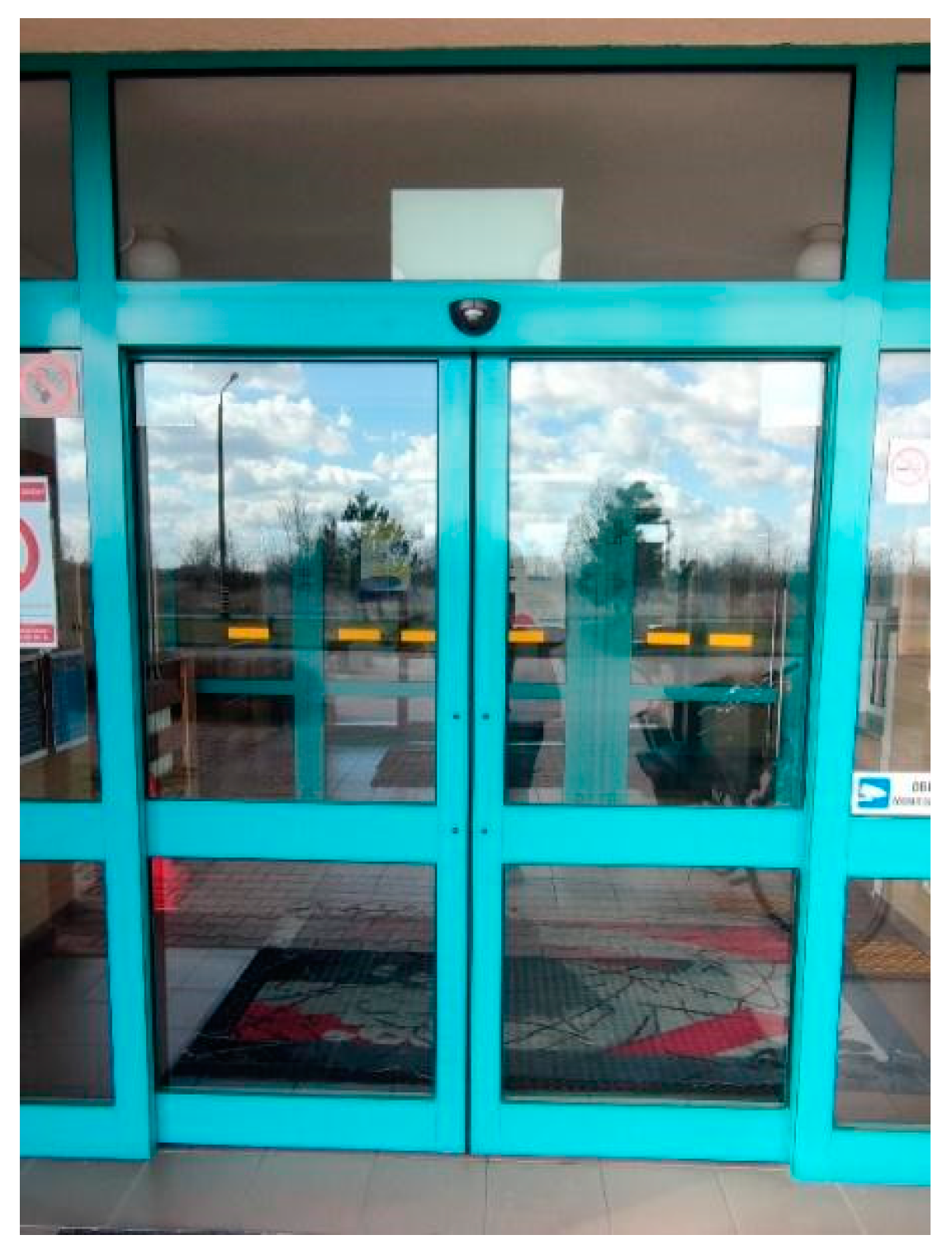

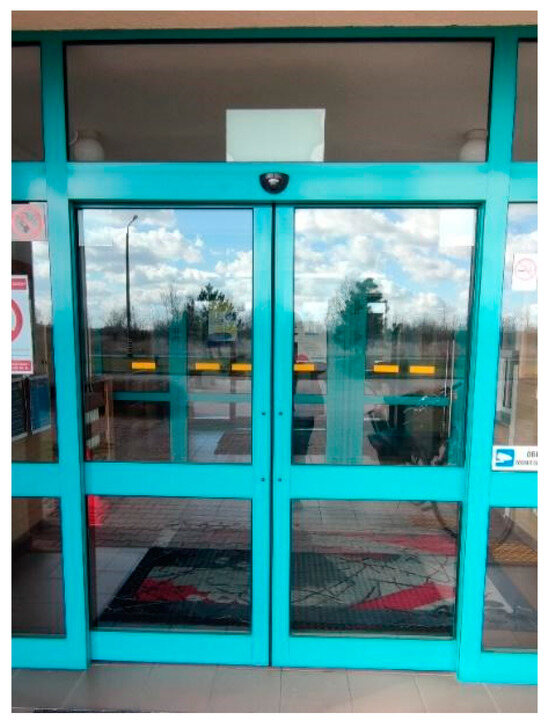

For people in wheelchairs, providing adequate space to maneuver is extremely important. A solution that eliminates the potential conflict between providing adequate space for maneuvering and the architectural vision is to install automatic doors that slide to the side, as shown in Figure 4, presenting an example from the Lower Silesian Special Educational Center No. 13 for blind and visually impaired students and those with other disabilities. This type of solution is helpful for children attending classes at this educational institution.

Figure 4.

Automatic doors as the first entrance door to the building of the Lower Silesian Special Educational Center No. 13 in Wrocław (own study).

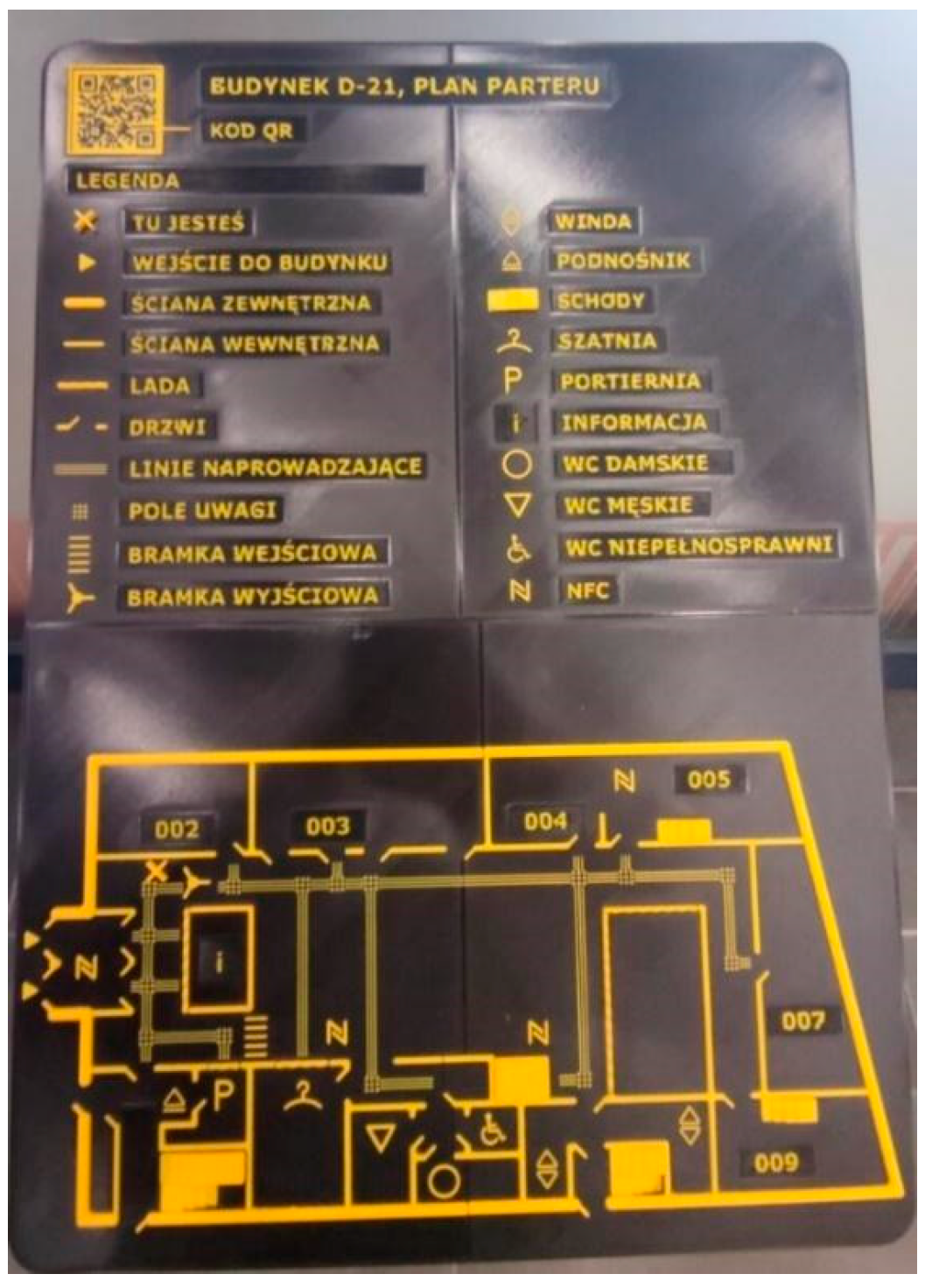

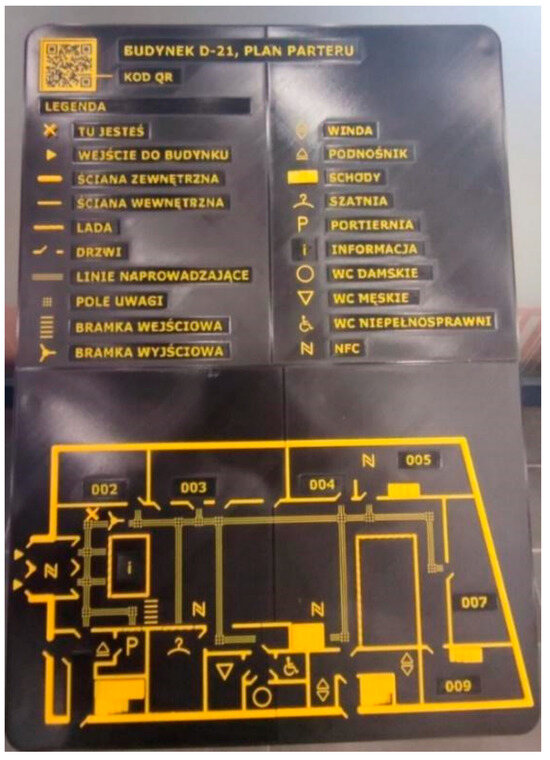

In the case of blind and visually impaired people, it is crucial to enable them to move efficiently around the building. Therefore, the solution presented by the Wrocław University of Science and Technology in the form of a typhlographic map allows them to learn about the building plan in the form of three-dimensional markers that refer to the layout of rooms, which allows them to move around the facility efficiently (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Typhlographic plan of the D-21 building of the Wrocław University of Science and Technology (own study).

An equally important factor making it easier to move around in the work environment is the correct management of office space, thanks to which each employee will be able to move freely.

Other suggestions for facilities for disabled people, may also include activities such as locating a bus stop near the entrances to buildings; marking sensitive places such as stairs, elevators, or glass doors with contrasting markings or inscriptions in Braille; or special overlays with protrusions that warn against approaching stairs or other dangerous places. Practical solutions that improve work comfort at the workplace include purchasing furniture with an adjustable height, storing documents at an appropriate height to which every employee can easily access, or planning light switches in corridors and sanitary rooms to provide easy access to these places for disabled people.

6. Summary and Conclusions

The aim of the article was achieved. The authors analyzed examples of facilities used, among others, at universities that allow disabled people to move safety and freely. An analysis of the problems that disabled people face in everyday life, as well as examples of facilities that enable access to public buildings, draws the following conclusions:

- -

- Employing a disabled person is possible, and the appropriate organization of office space and the willingness and commitment of the employer may result in fruitful cooperation.

- -

- Disabled people are valuable employees, which was confirmed by the presented research on the industrial sectors in which they are most often employed. The decisive factor in this matter is individual predispositions, skills, and, above all, the willingness of the employer to understand.

- -

- Facilities for the disabled have a positive impact on the functioning of the rest of society due to the elimination of architectural barriers. Such solutions include leveling the stop level to the road level, lowering curbs at pedestrian crossings, and installing elevators enabling travel with strollers or luggage.

Policies and programs aim to improve the labor market situation of persons with disabilities. According to the authors of [24], they should emphasize the importance of high-quality employment as a key ingredient of inclusion.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Ż.K. and K.T.; methodology, Ż.K. and K.T.; software, K.T. and J.W.; validation, K.T., Ż.K. and J.W.; formal analysis K.T. and Ż.K.; investigation, K.T. and J.W.; resources, K.T., Ż.K., J.W. and D.S.; data curation, K.T., Ż.K., J.W. and D.S.; writing—original draft preparation, K.T., Ż.K. and J.W.; writing—review and editing, K.T., Ż.K., J.W. and D.S.; visualization, K.T. and J.W.; supervision, Ż.K. and J.W.; project administration, J.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study did not receive external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wailes, E.; Mackenzie, F. Protecting people with communication disability from modern slavery: Supporting Sustainable Development Goals 8 and 16. Int. J. Speech-Lang. Pathol. 2023, 25, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosanic, A.; Petzold, J.; Martín-López, B.; Razanajatovo, M. An inclusive future: Disabled populations in the context of climate and environmental change. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2022, 55, 101159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón-Milán, M.J.; Calderón-Milán, B.; Barba-Sánchez, V. Labour inclusion of people with disabilities: What role do the social and solidarity economy entities play? Sustainability 2020, 12, 1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, P.B.; Oire, S.N.; Fabian, E.S.; Wewiorski, N.J. Negotiating reasonable workplace accommodations: Perspectives of employers, employees with disabilities, and rehabilitation service providers. J. Vocat. Rehabil. 2012, 37, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaye, H.S.; Jans, L.H.; Jones, E.C. Why don’t employers hire and retain workers with disabilities? J. Occup. Rehabil. 2011, 21, 526–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez, B.; Keys, C.; Balcazar, F. Employer attitudes toward workers with disabilities and their ADA employment rights: A literature review. J. Rehabil. Wash. 2000, 66, 4–16. [Google Scholar]

- Lengnick-Hall, M.L.; Gaunt, P.M.; Kulkarni, M. Overlooked and underutilized: People with disabilities are an untapped human resource. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2008, 47, 255–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.R.; Iwanaga, K.; Grenawalt, T.; Mpofu, N.; Chan, F.; Lee, B.; Tansey, T. Employer practices for integrating people with disabilities into the workplace: A scoping review. Rehabil. Res. Policy Educ. 2023, 37, 60–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khayatzadeh-Mahani, A.; Wittevrongel, K.; Nicholas, D.B.; Zwicker, J.D. Prioritizing barriers and solutions to improve employment for persons with developmental disabilities. Disabil. Rehabil. 2020, 42, 2696–2706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Conesa, F.J.; Romeo, M.; Yepes-Baldó, M. Labour inclusion of people with disabilities in Spain: The effect of policies and human resource management systems. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2020, 31, 785–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse, D.; Schur, L. Employment of people with disabilities following the ADA. Ind. Relat. A J. Econ. Soc. 2003, 42, 31–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ustawa z dnia 27 sierpnia 1997 r. o Rehabilitacji Zawodowej i Społecznej Oraz Zatrudnianiu Osób Niepełnosprawnych. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU19971230776/O/D19970776.pdf (accessed on 8 April 2024).

- The World Health Organization (WHO) International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Geneva: 2001. Available online: https://www.who.int/classifications/international-classification-of-functioning-disability-and-health (accessed on 8 April 2024).

- UNICEF. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/eca/sites/unicef.org.eca/files/IE_Webinar_Booklet_2.pdf (accessed on 8 April 2024).

- Ćwirlej-Sozańska, A.; Wilmowska-Pietruszyńska, A. Międzynarodowa Klasyfikacja Funkcjonowania, Niepełnosprawności i Zdrowia-model biopsychospołeczny. Bezpieczeństwo Pr. Nauka I Prakt. 2015, 8, 11–13. [Google Scholar]

- Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-rights-persons-disabilities (accessed on 15 June 2024).

- Central Statistical Office, Stan zdrowia ludności Polski w 2009, 2014; Osoby niepełnosprawne w 2021 r. Warszawa. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/en/topics/living-conditions/social-assistance/disabled-people-in-2022,7,4.html (accessed on 22 May 2023).

- The State Fund for Rehabilitation of Disabled People, PFRON. Available online: https://www.pfron.org.pl (accessed on 22 May 2023).

- Szołtysek, J. Miasto dostosowane do potrzeb osób niepełnosprawnych: Przykład działań Częstochowy i Gliwic. Stud. Ekon. 2013, 175, 159–178. [Google Scholar]

- Garbat, M. Rehabilitacja zawodowa i zatrudnienie chronione osób z niepełnosprawnościami w Polsce—Geneza, rozwój i stan obecny. Niepełnosprawność–Zagadnienia Probl. Rozw. 2015, 1, 79–106. [Google Scholar]

- Giermanowska, E.; Racław, M. Pomiędzy polityką życia, emancypacją i jej pozorowaniem. Pytania o nowy model polityki społecznej wobec zatrudnienia osób niepełnosprawnych. Stud. Socjol. 2014, 2, 107–127. [Google Scholar]

- Roszewska, K. Zatrudnianie i aktywizacja zawodowa osób z niepełnosprawnościami (w:) Najważniejsze wyzwania po ratyfikacji przez Polskę Konwencji ONZ o prawach osób niepełnosprawnych, red. A Błaszczak 2012, 10, 49–55. Available online: https://tiny.pl/d9wh2 (accessed on 8 April 2024).

- Jędrzejczyk, A. Biuletyn Informacji Publicznej Rzecznika Praw Obywatelskich. Available online: https://bip.brpo.gov.pl/pl/content/konwencja-onz-o-prawach-osob-niepelnosprawnych (accessed on 8 April 2024).

- Shahidi, F.V.; Jetha, A.; Kristman, V.; Smith, P.M.; Gignac, M.A. The employment quality of persons with disabilities: Findings from a national survey. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2023, 33, 785–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).