Assessing Psychosocial Work Conditions: Preliminary Validation of the Portuguese Short Version of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire III

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Sample

2.3. Instrument

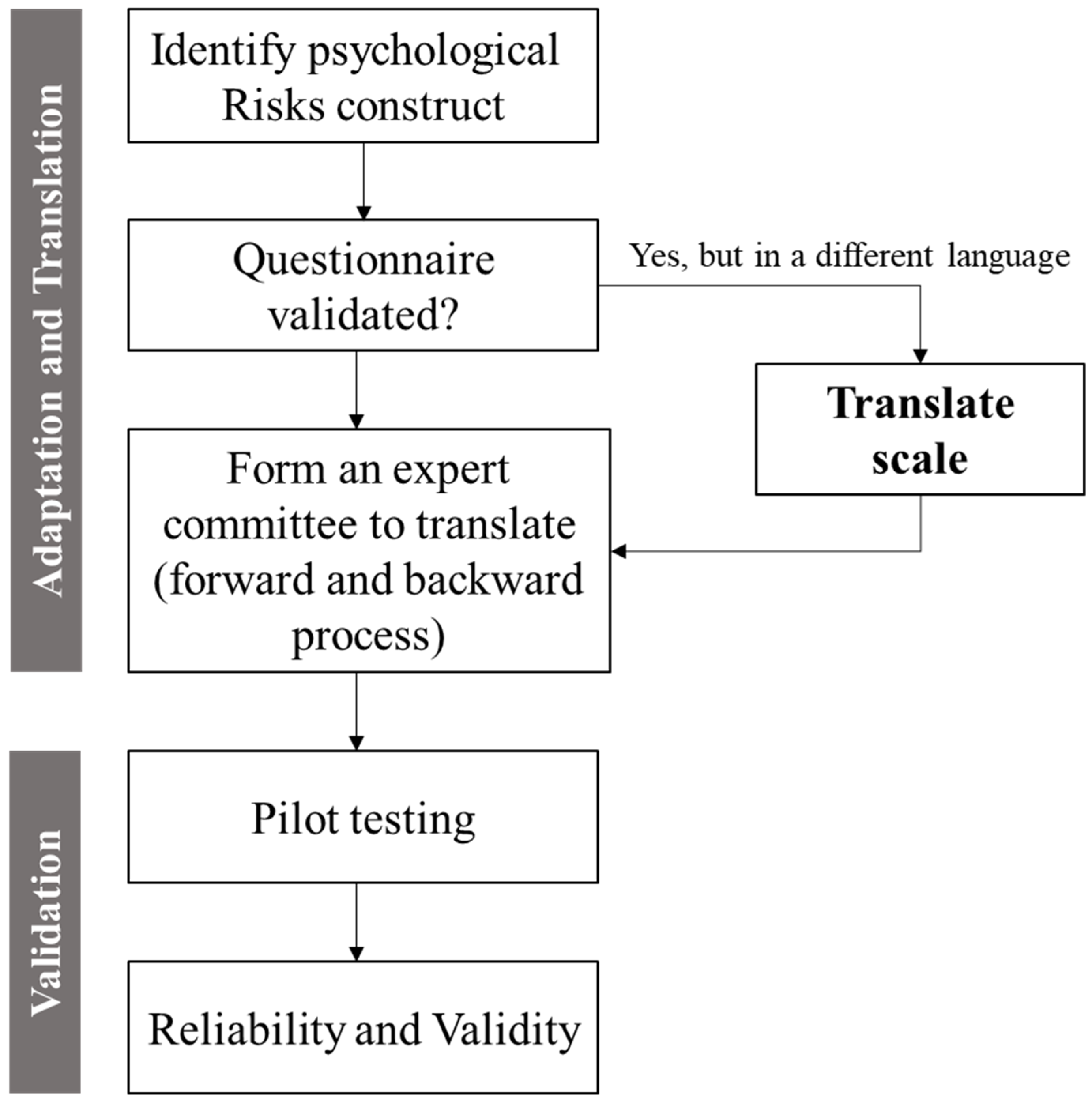

2.4. Translation and Validation Procedure

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kristensen, T.S.; Hannerz, H.; Hogh, A.; Borg, V. The Copenhagen psychosocial Questionnaire: A tool for the assessment and improvement of the psychosocial work environment. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2005, 31, 438–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulte, P.A.; Streit, J.M.K.; Sheriff, F.; Delclos, G.; Felknor, S.A.; Tamers, S.L.; Fendinger, S.; Grosch, J.; Sala, R. Potential scenarios and hazards in the work of the future: A systematic review of the peer-reviewed and gray literatures. Ann. Work Expo. Health 2020, 64, 786–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassard, J.; Teoh, K.; Thomson, L.; Blake, H. Understanding the cost of mental health at work: An integrative framework. In The SAGE Handbook of Organizational Wellbeing; Wall, T., Cooper, C.L., Brough, P., Eds.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021; pp. 9–25. [Google Scholar]

- Chirico, F.; Giorgi, G.; Magnavita, N. Addressing all the psychosocial risk factors in the workplace requires a comprehensive and interdisciplinary strategy and specific tools. J. Health Soc. Sci. 2023, 8, 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowrouzi-Kia, B.; Dong, J.; Gohar, B.; Hoad, M. Examining the Mental Health, Wellbeing, Work Participation and Engagement of Medical Laboratory Professionals in Ontario, Canada: An Exploratory Study. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 876883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organization. Emerging Risks and New Patterns of Prevention in a Changing World of Work; International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010; ISBN 978-92-2-123343-5. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_protect/@protrav/@safework/documents/publication/wcms_123653.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Burr, H.; Lange, S.; Freyer, M.; Formazin, M.; Rose, U.; Nielsen, M.L.; Conway, P.M. Physical and psychosocial working conditions as predictors of 5-year changes in work ability among 2078 employees in Germany. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2022, 95, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deady, M.; Arena, A.; Sanatkar, S.; Gayed, A.; Manohar, N.; Petrie, K.; Harvey, S.B. Psychological workplace injury and incapacity: A call for action. J. Ind. Relat. 2024, 00221856241258561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Torres, L.D.; Teoh, K.; Leka, S. The impact of national legislation on psychosocial risks on organizational action plans, psychosocial working conditions, and employee work-related stress in Europe. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 302, 114987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivian, J.C.; Neto, H.V. A relação entre condições psicossociais de trabalho e rotatividade voluntária de trabalhadores. Int. J. Work. Cond. 2020, 20, 51–70. [Google Scholar]

- Mateos-González, L.; Rodríguez-Suárez, J.; Llosa, J.A.; Agulló-Tomás, E.; Herrero, J. Influence of Job Insecurity on Musculoskeletal Disorders: A Mediation Model with Nursing Aides. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordem dos Psicólogos Portugueses. Prosperidade e Sustentabilidade das Organizações—Relatório do Custo do Stresse e dos Problemas de Saúde Psicológica no Trabalho, em Portugal; Ordem dos Psicólogos Portugueses: Lisboa, Portugal, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Dias, L.; Vergara, L. O uso do COPSOQ como ferramenta auxiliar de avaliação em ergonomia. In Proceedings of the IX Congresso Brasileiro de Engenharia de Produção, Ponta Grossa, Brazil, 4–6 December 2019; Available online: http://aprepro.org.br/conbrepro/2019/anais/arquivos/09302019_200933_5d928ba597c59.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- EU-OSHA. Managing Psychosocial Risks in European Micro and Small Enterprises: Qualitative Evidence from the Third European Survey of Enterprises on New and Emerging Risks; European Agency for Safety and Health at Work: Bilbao, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahan, C.; Baydur, H.; Demiral, Y. A novel version of Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaiere-3: Turkish validation study. Arch. Environ. Occup. Health 2019, 74, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pejtersen, J.H.; Kristensen, T.S.; Borg, V.; Bjorner, J.B. The second version of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire. Scand. J. Public Health 2010, 38 (Suppl. S3), 8–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristensen, T.S. A questionnaire is more than a questionnaire. Scand. J. Public Health 2010, 38 (Suppl. S3), 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucero-Perez, M.R.; Sabastizagal, I.; Astete-Cornejo, J.; Burgos, M.A.; Villarreal-Zegarra, D.; Moncada, S. Validation of the medium and short version of CENSOPAS-COPSOQ: A psychometric study in the Peruvian population. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 45003:2021; Occupational Health and Safety Management-Psychological Health and Safety at Work-Guidelines for Managing Psychosocial Risks. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/64283.html (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- ISO 45001:2018; Occupational Health and Safety Management Systems-Requirements with Guidance for Use. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/63787.html#amendment (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- ISO 9001:2015; Quality Management Systems-Requirements. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/62085.html#amendment (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Fernandes, C.; Pereira, A. Implementing psychosocial risk management in industrial SMEs: What does practice tells us? Occup. Environ. Med. 2021, 73, A200–A201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthelsen, H.; Hakanen, J.; Kristensen, T.S.; Lönnblad, A.; Westerlund, H. A qualitative study on the content validity of the social capital scales in the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ II). Scand. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2016, 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burr, H.; Berthelsen, H.; Moncada, S.; Nübling, M.; Dupret, E.; Demiral, Y.; Oudyk, J.; Kristensen, T.S.; Llorens, C.; Navarro, A.; et al. The third version of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire. Saf. Health Work 2019, 10, 482–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ose, S.O.; Lohmann-Lafrenz, S.; Bernstrøm, V.H.; Berthelsen, H.; Marchand, G.H. The Norwegian version of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ III): Initial validation study using a national sample of registered nurses. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0289739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, C.; Pereira, A. Exposure to psychosocial risk factors in the context of work: A systematic review. Rev. Saúde Pública 2016, 50, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, A.; Nübling, M.; Hammer, A.; Manser, T.; Rieger, M.A. Comparing perceived psychosocial working conditions of nurses and physicians in two university hospitals in Germany with other German professionals—Feasibility of scale conversion between two versions of the German Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ). J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 2020, 15, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, A.; Bem-Haja, P.; Alberty, A.; Brito-Costa, S.; Fernández, M.I.R.; Silva, C.; Almeida, H. Capacidade para o trabalho e fatores psicossociais de saúde mental: Uma amostra de profissionais de saúde portugueses. Int. J. Dev. Educ. Psychol.—INFAD Rev. Psicol. 2015, 2, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nübling, M.; Vomstein, M.; Schmidt, S.G.; Gregersen, S.; Dulon, M.; Nienhaus, A. Psychosocial work load and stress in the geriatric care. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotrim, T.; Carvalhais, J.; Neto, C.; Teles, J.; Noriega, P.; Rebelo, F. Determinants of sleepiness at work among railway control workers. Appl. Ergon. 2017, 58, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, J.D.; O’Sullivan, L.W. Musculoskeletal disorder prevalence and psychosocial risk exposures by age and gender in a cohort of office-based employees in two academic institutions. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2015, 46, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado, R.; Pérez-Franco, J.; Saavedra, N.; Fuentealba, C.; Alarcón, A.; Marchetti, N.; Aranda, W. Validación de un cuestionario para evaluar riesgos psicosociales en el ambiente laboral en Chile. Rev. Média De Chile 2012, 140, 1154–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pournik, O.; Ghalichi, L.; TehraniYazdi, A.; Tabatabaee, S.M.; Ghaffari, M.; Vingard, E. Measuring psychosocial exposures: Validation of the persian of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ). Med. J. Islam. Repub. Iran 2015, 29, 221. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Prada, M.; González-Cabrera, J.; Iribar-Ibabe, C.; Peinado, J.M. Riesgos psicosociales y estrés como predictores del burnout en médicos internos residentes en el Servicio de Urgencias. Gac. Médica Mex. 2017, 153, 450–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosário, S.; Azevedo, L.F.; Fonseca, J.A.; Nienhaus, A.; Nübling, M.; Costa, J.T. The portuguese long version of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire II (COPSOQ II)—A validation study. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 2017, 12, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breedt, J.E.; Marais, B.; Patricios, J. The psychosocial work conditions and mental well-being of independent school heads in South Africa. SA J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2023, 21, a2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moncada, S.; Utzet, M.; Molinero, E.; Llorens, C.; Moreno, N.; Galtés, A.; Navarro, A. The Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire II (COPSOQ II) in Spain—A tool for psychosocial risk assessment at the workplace. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2013, 57, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotrim, T.; Bem-Haja, P.; Amaral, V.; Pereira, A.; Silva, C.F. Evolução do questionário Psicossocial de Copenhaga: Do COPSOQ II para o COPSOQ III. Int. J. Work. Cond. 2017, 14, 105–115. [Google Scholar]

- Nübling, M.; Burr, H.; Moncada, S.; Kristensen, T.S. COPSOQ international network: Co-operation for research and assessment of psychosocial factors at work. Public Health Forum 2014, 22, 18–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lluís, S.M.; Serrano, C.L.; Nicás, S.S.; Soler, D.M.; Giné, A.N. La tercera versión de COPSOQ-istas21. Un instrumento internacional actualizado para la prevención de riesgos psicosociales en el trabajo. Rev. Española Salud Pública 2021, 95, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, M.; Hill, A. Investigação por Questionário, 2nd ed.; Edições Sílabo: Lisboa, Portugal, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Tsang, S.; Royse, C.F.; Terkawi, A.S. Guidelines for developing, translating, and validating a questionnaire in perioperative and pain medicine. Saudi J. Anaesth. 2017, 11 (Suppl. S1), S80–S89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jääskeläinen, R. Think-aloud protocol studies into translation: An annotated bibliography. Target. Int. J. Transl. Stud. 2002, 14, 107–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications and Programming, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Costello, A.B.; Osborne, J.W. Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2005, 10, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 3rd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 6th ed.; Pearson Education: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle, J.L. Amos 22 User’s Guide; SPSS: Chicago, IL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog, K.G.; Sörbom, D. LISREL 8.7 for Windows; Computer Software; Scientific Software International, Inc.: Lincolnwood, IL, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson Prentice-Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacker, R.E.; Lomax, R.G. A Beginner’s Guide to Structural Equation Modeling; Routledge Academic: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, S. Riscos Psicossociais: Uma área de intervenção psicológica. In Avaliar, Intervir e Prevenir os Riscos Psicossociais: Práticas e Recomendações; Antunes, S., Pereira, A., Eds.; Ordem dos Psicólogos Portugueses: Lisboa, Portugal, 2023; pp. 25–62. ISBN 978-989-53170-8-0. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, A.; Näswall, K. Job insecurity and trust: Uncovering a mechanism linking job insecurity to well-being. Work Stress 2019, 33, 22–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, J.; Wahrendorf, M. (Eds.) Work Stress and Health in a Globalized Economy: The Model of Effort-Reward Imbalance; Springer International Publishing/Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU-OSHA. Management of Psychosocial Risks in European Workplaces: Evidence from the Second European Survey of Enterprises on New and Emerging Risks (ESENER-2); European Agency for Safety and Health at Work: Bilbao, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Nicás, S.; Moncada, S.; Llorens, C.; Navarro, A. Working conditions and health in Spain during COVID-19 pandemic: Minding the gap. Saf. Sci. 2021, 134, 105064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smallwood, N.; Willis, K. Mental health among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Respirology 2021, 26, 1016–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurapov, A.; Kalaitzaki, A.; Keller, V.; Danyliuk, I.; Kowatsch, T. The mental health impact of the ongoing Russian-Ukrainian war 6 months after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1134780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Halbusi, H.; Tehseen, S.; Hamid, F.A.H.; Afthanorhan, A. A Study of Organizational Justice on the Trust in Organization under the Mediating Role of Ethical Leadership. Bus. Ethics Leadersh. 2018, 2, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Zhang, S.C.; Glerum, D.R. Job satisfaction. In Essentials of Job Attitudes and Other Workplace Psychological Constructs; Sessa, V.I., Bowling, N.A., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 207–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, T.C.; Hershcovis, M.S. Interpersonal relationships at work. In APA Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Zedeck, S., Ed.; Maintaining, Expanding, and Contracting the Organization; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; Volume 3, pp. 223–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clausen, T.; Borg, V. Job demands, job resources and meaning at work. J. Manag. Psychol. 2011, 26, 665–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobb, E.P. Managing Psychosocial Hazards and Work-Related Stress in Today’s Work Environment: International Insights for U.S. Organizations; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geibel, H.V.; Otto, K. Commitment is the key: A moderated mediation model linking leaders’ resources, work engagement, and transformational leadership behavior. Psychol. Rep. 2022, 126, 1977–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, P.W.; Schlünssen, V.; Fonager, K.; Bønløkke, J.H.; Hansen, C.D.; Bøggild, H. Association of perceived work pace and physical work demands with occupational accidents: A cross-sectional study of ageing male construction workers in Denmark. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundqvist, D.; Reineholm, C.; Ståhl, C.; Wallo, A. The impact of leadership on employee well-being: On-site compared to working from home. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthelsen, H.; Owen, M.; Westerlund, H. Does workplace social capital predict care quality through job satisfaction and stress at the clinic? A prospective study. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, A.; Prætorius, T.; Török, E.; Hvidtfeldt, U.A.; Hasle, P.; Rod, N.H. The impact of work-place social capital in hospitals on patient-reported quality of care: A cohort study of 5205 employees and 23,872 patients in Denmark. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göbel, J.; Schmidt, M.; Seifried-Dübon, T.; Linden, K.; Degen, L.; Rind, E.; Eilerts, A.-L.; Pieper, C.; Grot, M.; Werners, B.; et al. Higher Work-Privacy Conflict and Lower Job Satisfaction in GP Leaders and Practice Assistants Working Full-Time Compared to Part-Time: Results of the IMPROVE job Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Kwak, S. The effect of sleep disturbance on the association between work-family conflict and burnout in nurses: A cross-sectional study from South Korea. BMC Nurs. 2022, 21, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espassandim, T. SPMS: Navegando pelos desafios da transformação digital na saúde e riscos psicossociais. In Avaliar, Intervir e Prevenir os Riscos Psicossociais: Práticas e Recomendações; Antunes, S., Pereira, A., Eds.; Ordem dos Psicólogos Portugueses: Lisboa, Portugal, 2023; pp. 205–227. ISBN 978-989-53170-8-0. [Google Scholar]

| Domain | Dimension | Items |

|---|---|---|

| Exigências Laborais/Demands at Work | Exigências Quantitativas/Quantitative Demands | Q1. Com que frequência fica com trabalho atrasado?/Do you get behind with your work? (New) Q2. Com que frequência não tem tempo para completar todas as tarefas do seu trabalho?/How often do you not have time to complete all your work tasks? |

| Ritmo de Trabalho/Work Pace | Q3. Precisa de trabalhar muito rapidamente?/Do you have to work very fast? Q4. Trabalha a um ritmo elevado ao longo de toda a jornada de trabalho?/Do you work at a high pace throughout the day? (New) | |

| Exigências Emocionais/Emotional Demands | Q5. No seu trabalho tem de lidar com os problemas pessoais de outras pessoas?/Do you have to deal with other people’s personal problems at work? (New) Q6. O seu trabalho exige emocionalmente de si? Is your work emotionally demanding? | |

| Organização do Trabalho e Conteúdo/Work Organization and Job Contents | Influência no Trabalho/Influence at Work | Q7. Tem um elevado grau de influência nas decisões sobre o seu trabalho?/Do you have a large degree of influence on the decisions concerning your work? |

| Possibilidades de Desenvolvimento/Development Possibilities | Q8. O seu trabalho permite-lhe aprender coisas novas?/Do you have the possibility of learning new things through your work? Q9. O seu trabalho permite-lhe usar as suas competências ou habilitações? Can you use your skills or expertise in your work? | |

| Relações Sociais e Liderança/Interpersonal Relations and Leadership | Previsibilidade/Predictability | Q10. No seu local de trabalho é informado/a com antecedência sobre decisões importantes, mudanças ou planos para o futuro?/At your place of work, are you informed well in advance concerning, for example, important decisions, changes or plans for the future? Q11. Recebe toda a informação de que necessita para fazer bem o seu trabalho?/Do you receive all the information you need in order to do your work well? |

| Reconhecimento/Recognition | Q12. O seu trabalho é reconhecido e apreciado pela gestão de topo (administração, direção, gerência)?/Is your work recognized and appreciated by the management? | |

| Transparência do Papel Laboral/Role Clarity | Q13. O seu trabalho tem objetivos claros?/Does your work have clear objectives? | |

| Conflito de Papéis Laborais/Role Conflicts | Q14. Faz coisas no seu trabalho com que uns concordam mas outros não?/Are contradictory demands placed on you at work? Q15. Por vezes tem que fazer coisas que deveriam ser feitas de outra maneira?/Do you sometimes have to do things which ought to have been done in a different way? | |

| Qualidade da Liderança/Quality of Leadership | Em relação à sua chefia directa, até que ponto considera que …/To what extent would you say that your immediate superior … Q16. É bom/boa no planeamento do trabalho?/Are you good at work planning? Q17. É bom/boa a resolver conflitos?/Are you good at solving conflicts? | |

| Suporte Social de Colegas/Social Support from Colleagues | Q18. Com que frequência tem ajuda e apoio dos/as seus/suas colegas de trabalho, se necessário? How often do you get help and support from your colleagues, if necessary? | |

| Suporte Social de Superiores/Social Support from Supervisors | Q19. Com que frequência tem ajuda e apoio da sua chefia direta, se necessário?/How often do you get help and support from your immediate supervisor, if needed? | |

| Sentido de Pertença a Comunidade/Sense of Community at Work | Q20. Existe um bom ambiente de trabalho entre si e os/as seus/suas colegas?/Is there a good atmosphere between you and your colleagues? | |

| Capital Social/Social Capital | Justiça Organizacional/Organizational Justice | Q21. Os conflitos são resolvidos de uma forma justa?/Are conflicts resolved in a fair way? Q22. O trabalho é distribuído de forma justa?/Is the work distributed fairly? |

| Confiança Vertical/Vertical Trust | Q23. Os trabalhadores/as confiam na informação que lhes é transmitida pela gestão de topo (administração, direção, gerência)?/Can the employees trust the information that comes from the management? | |

| Organização do Trabalho e Conteúdo/Work Organization and Job Contents | Significado do Trabalho/Meaning of Work | Q24. O seu trabalho tem algum significado para si?/Is your work meaningful? |

| Interface Trabalho-Indivíduo/Work Individual Interface | Insegurança Laboral/Job Insecurity | Q25. Sente-se preocupado/a em ficar desempregado/a?/Are you worried about becoming unemployed? Q26. Sente-se preocupado/a com a dificuldade em encontrar outro trabalho se ficar desempregado/a?/Are you worried about it being difficult for you to find another job if you became unemployed? (New) |

| Insegurança com as Condições de Trabalho/Insecurity over Working Conditions (New) | Q27. Sente-se preocupado/a em ser transferido/a para outro posto de trabalho contra a sua vontade?/Are you worried about being transferred to another job against your will? | |

| Capital Social/Social Capital | Confiança vertical/ Vertical trust | Q28. A gestão de topo (administração, direção, gerência) confia nos seus trabalhadores para fazerem o seu trabalho bem?/Does the management trust the employees to do their work well? |

| Saúde e Bem-Estar/Health and Well-Being | Auto-Avaliação da Saúde/Self-Rated Health | Q29. Em geral, sente que a sua saúde é:/In general, would you say your health is: |

| Interface Trabalho-Indivíduo/ Work/Individual Interface | Satisfação com o Trabalho/Job Satisfaction | Em relação ao seu trabalho em geral, quão satisfeito está com …/Regarding your work in general. How pleased are you with … Q30. O seu trabalho de uma forma global?/Your job as a whole, everything taken into consideration? |

| Conflito Trabalho-Família/Work–Life Conflict | Q31. Há momentos em que precisa de estar no trabalho e em casa ao mesmo tempo?/Are there times when you need to be at work and at home at the same time? (New) Q32. Sinto que o meu trabalho me exige tanta energia, que acaba por afetar a minha vida privada negativamente?/Do you feel that your work drains so much of your energy that it has a negative effect on your private life? Q33. Sinto que o meu trabalho me exige tanto tempo, que acaba por afetar a minha vida privada negativamente?/Do you feel that your work takes so much of your time that it has a negative effect on your private life? Q34. As exigências do meu trabalho interferem com a minha vida privada e familiar?/The demands of my work interfere with my private and family life (New) Q35. Devido ao meu trabalho tenho que alterar os meus planos familiares e pessoais?/Due to work-related duties, I have to make changes to my plans for private and family activities? (New) |

| Domain | Dimension | α | CR | AVE | M | SD | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Capital | 1. Vertical Trust | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.59 | 3.72 | 0.76 | 0.60 | −0.14 | −0.17 | −0.14 | 0.20 | 0.30 | 0.34 | 0.58 | 0.44 | 0.60 | −0.28 | 0.59 | 0.30 | 0.40 | 0.52 | −0.04 | 0.57 | −0.23 | 0.23 |

| 2. Organizational Justice | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.57 | 3.50 | 0.83 | - | −0.19 | −0.24 | −0.18 | 0.16 | 0.30 | 0.36 | 0.49 | 0.38 | 0.53 | −0.29 | 0.64 | 0.40 | 0.59 | 0.56 | −0.14 | 0.51 | −0.32 | 0.20 | |

| Demands at Work | 3. Quantitative Demands | 0.83 | 0.87 | 0.79 | 2.62 | 0.94 | - | 0.32 | 0.23 | 0.17 | 0.01 | 0.15 | −0.07 | −0.13 | −0.09 | 0.26 | −0.19 | −0.06 | −0.06 | −0.12 | 0.03 | −0.14 | 0.42 | −0.17 | |

| 4. Work Pace | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.65 | 3.46 | 0.76 | - | 0.27 | 0.06 | −0.02 | −0.10 | −0.16 | −0.07 | −0.19 | 0.18 | −0.18 | −0.11 | −0.10 | −0.14 | 0.09 | −0.11 | 0.38 | −0.01 | |||

| 5. Emotional Demands | 0.75 | 0.81 | 0.70 | 3.27 | 0.91 | - | 0.26 | 0.09 | 0.19 | −0.11 | −0.06 | −0.12 | 0.36 | −0.16 | −0.07 | −0.15 | −0.16 | 0.14 | −0.11 | 0.45 | −0.09 | ||||

| Work Organization and Job Contents | 6. Influence at Work | - | - | - | 3.55 | 0.98 | - | 0.32 | 0.42 | 0.29 | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.15 | 0.12 | −0.05 | 0.29 | 0.13 | 0.11 | ||||

| 7. Meaning of Work | - | - | - | 3.97 | 0.88 | - | 0.48 | 0.44 | 0.26 | 0.31 | 0.00 | 0.27 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.26 | −0.06 | 0.57 | −0.07 | 0.12 | ||||||

| 8. Development Possibilities | 0.73 | 0.74 | 0.58 | 3.86 | 0.86 | - | 0.40 | 0.29 | 0.44 | 0.05 | 0.29 | 0.25 | 0.23 | 0.29 | −0.06 | 0.45 | 0.01 | 0.13 | |||||||

| Interpersonal Relations and Leadership | 9. Recognition | - | - | - | 3.41 | 1.09 | - | 0.42 | 0.59 | −0.29 | 0.48 | 0.32 | 0.35 | 0.50 | −0.14 | 0.56 | −0.21 | 0.30 | |||||||

| 10. Role Clarity | - | - | - | 4.05 | 0.91 | - | 0.49 | −0.16 | 0.46 | 0.27 | 0.37 | 0.33 | −0.06 | 0.42 | −0.15 | 0.16 | |||||||||

| 11. Predictability | 0.75 | 0.76 | 0.63 | 3.44 | 0.87 | - | −0.29 | 0.58 | 0.34 | 0.41 | 0.52 | −0.09 | 0.51 | −0.21 | 0.23 | ||||||||||

| 12. Role Conflicts | 0.68 | 0.68 | 0.51 | 2.85 | 0.78 | - | −0.27 | −0.10 | −0.25 | −0.17 | 0.18 | −0.24 | 0.41 | −0.27 | |||||||||||

| 13. Quality of Leadership | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.67 | 3.62 | 0.90 | - | 0.39 | 0.42 | 0.65 | −0.01 | 0.50 | −0.24 | 0.19 | ||||||||||||

| 14. Social Support from colleagues | - | - | - | 3.78 | 0.89 | - | 0.48 | 0.57 | −0.14 | 0.27 | −0.16 | 0.16 | |||||||||||||

| 15. Sense of Community at work | - | - | - | 4.08 | 0.82 | - | 0.41 | −0.16 | 0.34 | −0.25 | 0.23 | ||||||||||||||

| 16. Social Support from supervisors | - | - | - | 3.71 | 1.07 | - | −0.12 | 0.45 | −0.24 | 0.16 | |||||||||||||||

| Work/Individual Interface | 17. Job insecurity (working conditions) | 0.77 | 0.79 | 0.56 | 2.48 | 1.05 | - | −0.08 | 0.26 | −0.18 | |||||||||||||||

| 18. Job satisfaction | - | - | - | 3.47 | 0.90 | - | −0.25 | 0.34 | |||||||||||||||||

| 19. Work-life conflicts | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.67 | 2.74 | 0.84 | − | −0.27 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Health and Well-Being | 20. Self-rated Health | - | - | - | 3.25 | 0.95 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pinto, A.; Carvalho, C.; Mónico, L.S.; Moio, I.; Alves, J.; Lima, T.M. Assessing Psychosocial Work Conditions: Preliminary Validation of the Portuguese Short Version of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire III. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7479. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16177479

Pinto A, Carvalho C, Mónico LS, Moio I, Alves J, Lima TM. Assessing Psychosocial Work Conditions: Preliminary Validation of the Portuguese Short Version of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire III. Sustainability. 2024; 16(17):7479. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16177479

Chicago/Turabian StylePinto, Ana, Carla Carvalho, Lisete S. Mónico, Isabel Moio, Joel Alves, and Tânia M. Lima. 2024. "Assessing Psychosocial Work Conditions: Preliminary Validation of the Portuguese Short Version of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire III" Sustainability 16, no. 17: 7479. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16177479