Workforce Sustainability in Our Aging Society: Exploring How the Burden–Burnout Mechanism Exacerbates the Turnover Intentions of Employees Who Combine Work and Informal Eldercare

Abstract

:1. Introduction

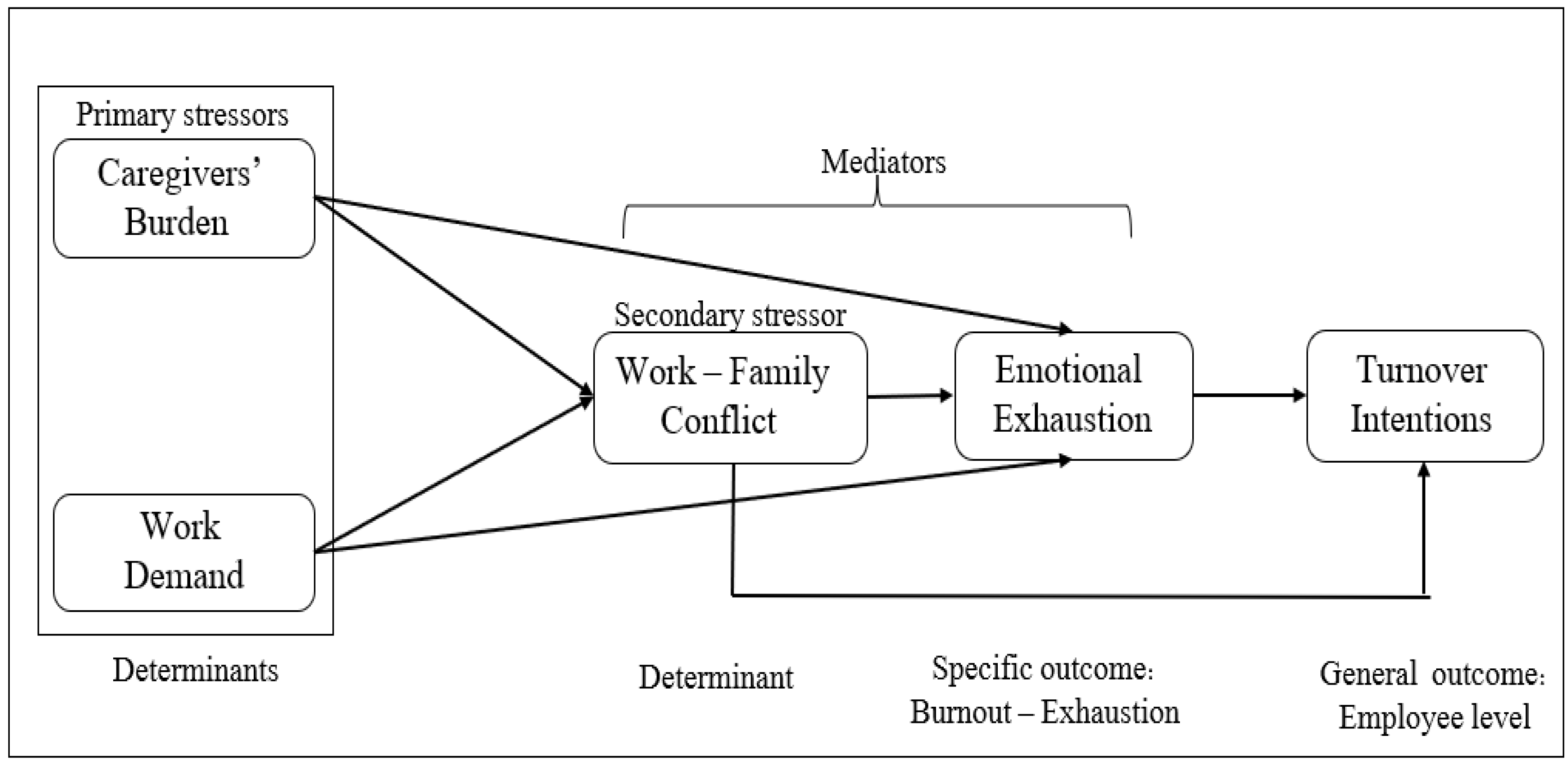

1.1. Theoretical Framework

1.2. Turnover Intention among Informal Caregivers

1.3. Informal Caregivers’ Burden and Work Demand as Primary Stressors

1.4. The Mediation Role of the Work–Family Conflict as a Secondary Stressor and Exhaustion

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sample Size

2.2. Participants and Data Collection

2.3. Ethical Considerations

2.4. Variables and Measurements

2.4.1. Demographic Characteristics

2.4.2. Variables Related to the Care of the Elderly

2.4.3. Study Measures

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

3.2. The Care and Support of the Elderly

3.3. Correlations between Study Variables

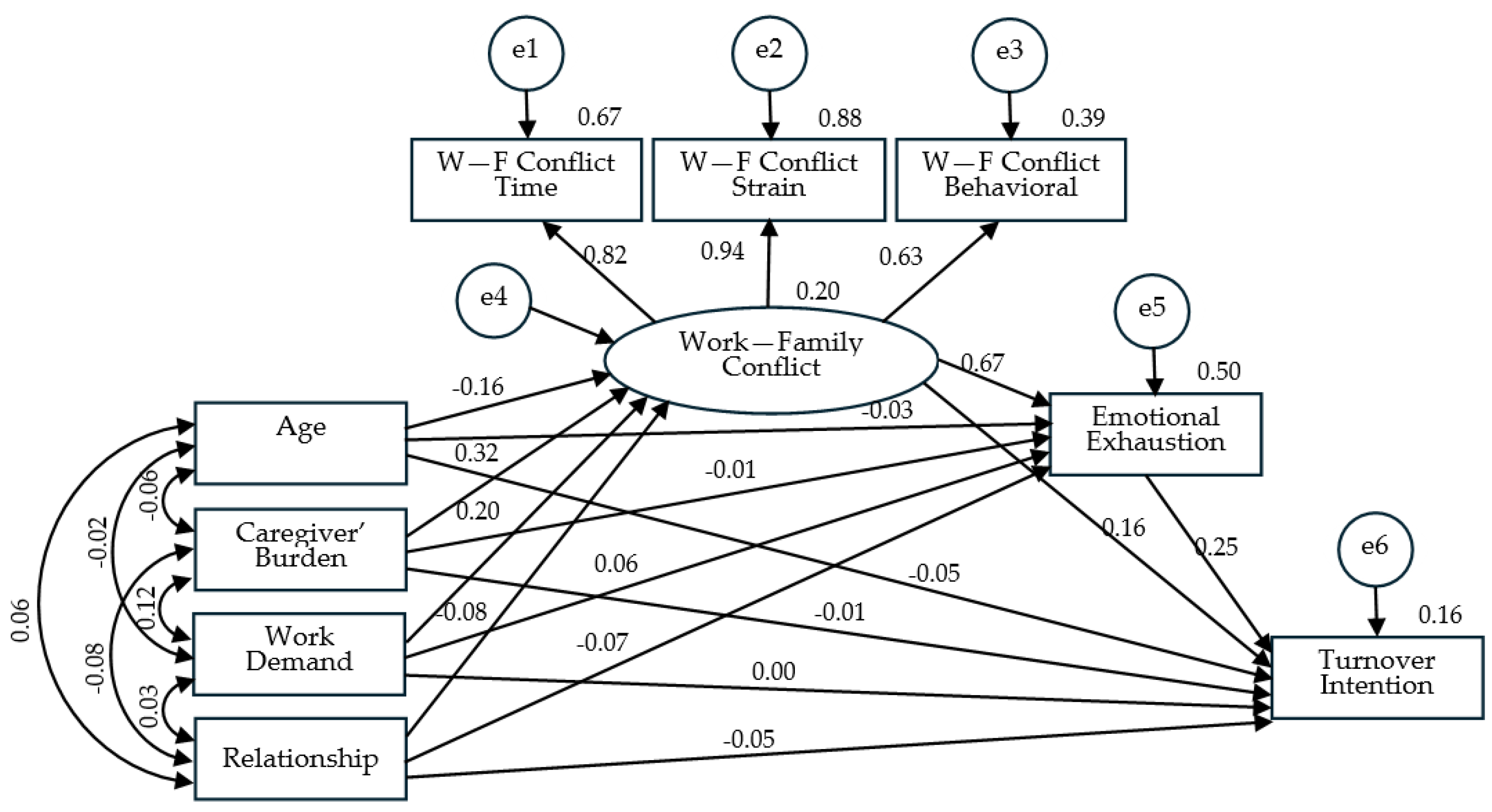

3.4. Structural Equation Modeling for Examining Relationships between Study Variables

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

6. Practical Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. Ageing. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/ageing#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 28 July 2024).

- Colombo, F.; Llena-Nozal, A.; Mercier, J.; Tjadens, F. Help Wanted? Providing and Paying for Long-Term Care. In OECD Health Policy Studies; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lilly, M.B.; Laporte, A.; Coyte, P.C. Do they care too much to work? The influence of caregiving intensity on the labour force participation of unpaid caregivers in Canada. J. Health Econ. 2010, 29, 895–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Houtven, C.; Carmichael, F.; Jacobs, J.; Coyte, P.C. The economics of informal care. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Economics and Finance; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greaves, C.E.; Parker, S.L.; Zacher, H.; Jimmieson, N.L. Turnover intentions of employees with informal eldercare responsibilities: The role of core self-evaluations and supervisor support. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2015, 82, 79–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Careres UK. Juggling Work and Unpaid Care a Growing Issue. 2019. ISBN Number 978-1-5272-3681-3 Publication code UK4078_0119. © Carers UK, January 2019. Available online: https://www.carersuk.org/media/no2lwyxl/juggling-work-and-unpaid-care-report-final-web.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2024).

- Bauer, J.M.; Sousa-Poza, A. Impacts of informal caregiving on caregiver employment, health, and family. J. Popul. Ageing 2015, 8, 113–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montano, D.; Peter, R. Informal care-giving and the intention to give up employment: The role of perceived supervisor behaviour in a cohort of German employees. Eur. J. Ageing 2021, 19, 575–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasheed, M.; Iqbal, S.; Mustafa, F. Work-family conflict and female employees’ turnover intentions. Gend. Manag. An. Int. J. 2018, 33, 636–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skelton, A.R.; Nattress, D.; Dwyer, R.J. Predicting manufacturing employee turnover intentions. J. Econ. Financ. Adm. Sci. 2020, 25, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boamah, S.A.; Hamadi, H.Y.; Havaei, F.; Smith, H.; Webb, F. Striking a balance between work and play: The effects of work–life interference and burnout on faculty turnover intentions and career satisfaction. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clancy, R.L.; Fisher, G.G.; Daigle, K.L.; Henle, C.A.; McCarthy, J.; Fruhauf, C.A. Eldercare and work among informal caregivers: A multidisciplinary review and recommendations for future research. J. Bus. Psychol. 2020, 35, 9–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DePasquale, N.; Davis, K.D.; Zarit, S.H.; Moen, P.; Hammer, L.B.; Almeida, D.M. Combining formal and informal caregiving roles: The psychosocial implications of double-and triple-duty care. J. Gerontol. Ser. B: Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2016, 71, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, C.; Turner, T. Formal and informal long term care work: Policy conflict in a liberal welfare state. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2017, 37, 134–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Jex, S.; Zhang, W.; Ma, J.; Matthews, R.A. Eldercare demands and time theft: Integrating family-to-work conflict and spillover–crossover perspectives. J. Bus. Psychol. 2020, 35, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, L.M. Family care responsibilities and employment: Exploring the impact of type of family care on work–family and family–work conflict. J. Fam. Issues 2013, 34, 113–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, G.; Blake, R.S.; Goodman, D. Does turnover intention matter? Evaluating the usefulness of turnover intention rate as a predictor of actual turnover rate. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2016, 36, 240–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Whitford, A.B. Exit, voice, loyalty, and pay: Evidence from the public workforce. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2007, 18, 647–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, M.A.; Walker, M.H.; Kaskie, B.P. Strapped for time or stressed out? Predictors of work interruption and unmet need for workplace support among informal elder caregivers. J. Aging Health 2019, 31, 631–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, J.C.; Allen, S.M.; Goldscheider, F.; Intrator, O. Spousal caregiving in late midlife versus older ages: Implications of work and family obligations. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2008, 63, S229–S238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silverstein, M.; Giarrusso, R. Aging and family life: A decade review. J. Marriage Fam. 2010, 72, 1039–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Principi, A.; Lamura, G.; Sirolla, C.; Mestheneos, L.I.Z.; Bień, B.; Brown, J.; Krevers, B.; Melchiorre, M.G.; Doehner, H. Work restrictions experienced by midlife family care-givers of older people: Evidence from six European countries. Ageing Soc. 2014, 34, 209–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amstad, F.T.; Meier, L.L.; Fasel, U.; Elfering, A.; Semmer, N.K. A meta-analysis of work–family conflict and various outcomes with a special emphasis on cross-domain versus matching-domain relations. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2011, 16, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvano, L. Tug of war: Caring for our elders while remaining productive at work. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2013, 27, 204–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossek, E.E.; Colquitt, J.A.; Noe, R.A. Caregiving decisions, well-being, and performance: The effects of place and provider as a function of dependent type and work-family climates. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, W.W.Y.; Nielsen, K.; Sprigg, C.A.; Kelly, C.M. The demands and resources of working informal caregivers of older people: A systematic review. Work Stress 2022, 36, 105–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, C.; Cross, C. Blurred lines: Work, eldercare and HRM. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2021, 32, 1460–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P.M.; Meyer, B.D.; Pencavel, J.; Roberts, M.J. The extent and consequences of job turnover. Brook. Pap. Econ. Act. Microecon. 1994, 1994, 177–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gérain, P.; Zech, E. Informal caregiver burnout? Development of a theoretical framework to understand the impact of caregiving. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouget, D.; Saraceno, C.; Spasova, S. Towards new work-life balance policies for those caring for dependent relatives. Soc. Policy Eur. Union State Play 2017, 27, 28. [Google Scholar]

- United Nation. Promote Sustained, Inclusive and Sustainable Economic Growth, Full and Productive Employment and Decent Work for All. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal8 (accessed on 28 July 2024).

- Schneider, U.; Trukeschitz, B.; Mühlmann, R.; Ponocny, I. “Do I stay or do I go?”—Job change and labor market exit intentions of employees providing informal care to older adults. Health Econ. 2013, 22, 1230–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mobley, W.H. Some unanswered questions in turnover and withdrawal research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1982, 7, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffeth, R.W.; Hom, P.W.; Gaertner, S. A meta-analysis of antecedents and correlates of employee turnover: Update, moderator tests, and research implications for the next millennium. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 463–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hom, P.W.; Kinicki, A.J. Toward a greater understanding of how dissatisfaction drives employee turnover. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 975–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, R.P. Turnover theory at the empirical interface: Problems of fit and function. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2002, 27, 346–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tett, R.P.; Meyer, J.P. Job satisfaction, organizational commitment, turnover intention, and turnover: Path analyses based on meta-analytic findings. Pers. Psychol. 1993, 46, 259–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, A.; Weisberg, J. Exploring turnover intentions among three professional groups of employees. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2006, 9, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galiatsatos, P.; Gurley, A.; Daniel Hale, W. Policy and advocacy for informal caregivers: How state policy influenced a community initiative. J. Public Health Policy 2017, 38, 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burch, K.A.; Dugan, A.G.; Barnes-Farrell, J.L. Understanding what eldercare means for employees and organizations: A review and recommendations for future research. Work Aging Retire. 2019, 5, 44–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robison, J.; Fortinsky, R.; Kleppinger, A.; Shugrue, N.; Porter, M. A broader view of family caregiving: Effects of caregiving and caregiver conditions on depressive symptoms, health, work, and social isolation. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2009, 64, 788–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiao, C.Y.; Wu, H.S.; Hsiao, C.Y. Caregiver burden for informal caregivers of patients with dementia: A systematic review. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2015, 62, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sörensen, S.; Duberstein, P.; Gill, D.; Pinquart, M. Dementia care: Mental health effects, intervention strategies, and clinical implications. Lancet Neurol. 2006, 5, 961–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, S.; Badiye, A.; Kelkar, G. The dementia caregiver—A primary care approach. South. Med. J. 2008, 101, 1246–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarit, S.H.; Todd, P.A.; Zarit, J.M. Subjective burden of husbands and wives as caregivers: A longitudinal study. Gerontologist 1986, 26, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gérain, P.; Zech, E. Do informal caregivers experience more burnout? A meta-analytic study. Psychol. Health Med. 2021, 26, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oldenkamp, M.; Bültmann, U.; Wittek, R.P.; Stolk, R.P.; Hagedoorn, M.; Smidt, N. Combining informal care and paid work: The use of work arrangements by working adult-child caregivers in the Netherlands. Health Soc. Care Community 2018, 26, e122–e131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, N.; Chen, C.C.; Choi, J.; Zou, Y. Sources of work-family conflict: A Sino-U.S. comparison of the effects of work and family demands. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; De Jonge, J.; Janssen, P.P.; Schaufeli, W.B. Burnout and engagement at work as a function of demands and control. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2001, 27, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyar, S.L.; Carr, J.C.; Mosley, D.C., Jr.; Carson, C.M. The development and validation of scores on perceived work and family demand scales. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2007, 67, 100–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Dollard, M.F. How job demands affect partners’ experience of exhaustion: Integrating work-family conflict and crossover theory. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 901–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyar, S.L.; Maertz, C.P., Jr.; Mosley, D.C., Jr.; Carr, J.C. The impact of work/family demand on work-family conflict. J. Manag. Psychol. 2008, 23, 215–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, D.S.; Kacmar, K.M.; Williams, L.J. Construction and initial validation of a multidimensional measure of work-family conflict. J. Vocat. Behav. 2000, 56, 249–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, S.; Purohit, Y.S.; Godshalk, V.M.; Beutell, N.J. Work and family variables, entrepreneurial career success, and psychological well-being. J. Vocat. Behav. 1996, 48, 275–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, D.S.; Kacmar, K.M. Work-family conflict in the organization: Do life role values make a difference? J. Manag. 2000, 26, 1031–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Beutell, N.J. Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1985, 10, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, N.; Chapman, J. Work-life balance and family friendly policies. Evid. Base A J. Evid. Rev. Key Policy Areas 2013, 4, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhéaume, A. Job characteristics, emotional exhaustion, and work–family conflict in nurses. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2022, 44, 548–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugan, A.G.; Fortinsky, R.H.; Barnes-Farrell, J.L.; Kenny, A.M.; Robison, J.T.; Warren, N.; Cherniack, M.G. Associations of eldercare and competing demands with health and work outcomes among manufacturing workers. Community Work Fam. 2016, 19, 569–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.H.; Brown, R.; Bowers, B.J.; Chang, W.Y. Work-to-family conflict as a mediator of the relationship between job satisfaction and turnover intention. J. Adv. Nurs. 2015, 71, 2350–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, Y.; Inoue, T.; Harada, H.; Oike, M. Job control, work-family balance and nurses’ intention to leave their profession and organization: A comparative cross-sectional survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2016, 64, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leineweber, C.; Westerlund, H.; Chungkham, H.S.; Lindqvist, R.; Runesdotter, S.; Tishelman, C. Nurses’ practice environment and work–family conflict in relation to burn out: A multilevel modelling approach. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e96991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. A model of burnout and life satisfaction amongst nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 2000, 32, 454–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Burn-out an “Occupational Phenomenon”: International Classification of Diseases. 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/28-05-2019-burn-out-an-occupational-phenomenon-international-classification-of-diseases (accessed on 28 July 2024).

- Cropanzano, R.; Rupp, D.E.; Byrne, Z.S. The relationship of emotional exhaustion to work attitudes, job performance, and organizational citizenship behaviors. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyei-Poku, I. The influence of fair supervision on employees’ emotional exhaustion and turnover intentions. Manag. Res. Rev. 2019, 42, 1116–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. J. Organ. Behav. Int. J. Ind. Occup. Organ. Psychol. Behav. 2004, 25, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Alone together: Comparing communal versus individualistic resiliency. In Beyond Coping: Meeting Goals, Vision, and Challenges; Frydenberg, E., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002; pp. 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social,behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, P.J.; Troth, A.C. Common method bias in applied settings: The dilemma of researching in organizations. Aust. J. Manag. 2020, 45, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials. In Handbook of Cross-Cultural Psychology; Triandis, H.C., Berry, J.W., Eds.; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 1980; Volume 2, pp. 137–164. [Google Scholar]

- Bédard, M.; Molloy, D.W.; Squire, L.; Dubois, S.; Lever, J.A.; O’Donnell, M. The Zarit Burden Interview: A new short version and screening version. Gerontologist 2001, 41, 652–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P.; Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E. Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey (MBI-GS). In MBI Manual; Maslach, C., Jackson, S.E., Leiter, M.P., Eds.; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, J.; Ma, H.; Zhou, Z.E.; Tang, H. Work-related use of information and communication technologies after hours (W_ICTs) and emotional exhaustion: A mediated moderation model. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 79, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellgren, J.; Sjöberg, A.; Sverke, M. Intention to quit: Effects of job satisfaction and job perceptions. In Feelings Work in Europe; Avallone, F., Arnold, J., de Witte, K., Eds.; Guerini: Milano, Italy, 1997; pp. 415–423. [Google Scholar]

- Sjöberg, A.; Sverke, M. The interactive effect of job involvement and organizational commitment on job turnover revisited: A note on the mediating role of turnover intention. Scand. J. Psychol. 2000, 41, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indices in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, J.B.; Stage, F.K.; King, J.; Nora, A.; Barlow, E.A. Reporting structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis results: A review. J. Educ. Res. 2006, 99, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrout, P.E.; Bolger, N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 422–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Converso, D.; Sottimano, I.; Viotti, S.; Guidetti, G. I’ll be a caregiver-employee: Aging of the workforce and family-to-work conflicts. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinarski-Peretz, H.; Halperin, D. Family care in our aging society: Policy, legislation and intergenerational relations: The case of Israel. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2022, 43, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayaalp, A.; Page, K.J.; Rospenda, K.M. Caregiver burden, work-family conflict, family-work conflict, and mental health of caregivers: A mediational longitudinal study. Work Stress 2021, 35, 217–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, D.; Aycan, Z. Nurses’ work demands and work–family conflict: A questionnaire survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2008, 45, 1366–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2002, 6, 307–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.D.; Hughes, K.; DeJoy, D.M.; Dyal, M.A. Assessment of relationships between work stress, work-family conflict, burnout and firefighter safety behavior outcomes. Saf. Sci. 2018, 103, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, L.; Wang, J.; Wang, L. Work-family conflict and burnout among Chinese doctors: The mediating role of psychological capital. J. Occup. Health 2012, 54, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, J.; McCormack, L.; Campbell, L.E. “You don’t know until you get there”: The positive and negative “lived” experience of parenting an adult child with 22q11. 2 deletion syndrome. Health Psychol. 2017, 36, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, T.D.; Herst, D.E.; Bruck, C.S.; Sutton, M. Consequences associated with work-to-family conflict: A review and agenda for future research. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2000, 5, 278–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haar, J.M.; Roche, M.; Taylor, D. Work-family conflict and turnover intentions of indigenous employees: The importance of the whanau/family for Maori. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 23, 2546–2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoff, A.; Reichert, M.; Hamblin, K.A.; Perek-Bialas, J.; Principi, A. Informal and formal reconciliation strategies of older peoples’ working carers: The European carers@ work project. Vulnerable Groups Incl. 2014, 5, 24264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, A.M.G.L.R.S.; da Silva Ramos, S.C.M.; Nunes, S.M.M.D. Managing an aging workforce: What is the value of human resource management practices for different age groups of workers? Tékhne 2014, 12, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Podsakoff, N.P.; Williams, L.J.; Huang, C.; Yang, J. Common Method Bias: It’s Bad, It’s Complex, It’s Widespread, and It’s Not Easy to Fix. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2024, 11, 17–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmichael, F.; Charles, S. The opportunity costs of informal care: Does gender matter? J. Health Econ. 2003, 22, 781–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halperin, D. Intergenerational relations: The views of older Jews and Arabs. J. Intergener. Relatsh. 2015, 13, 51–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavee, Y.; Katz, R. The family in Israel: Between tradition and modernity. Marriage Fam. Rev. 2003, 35, 193–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverstein, M.; Lowenstein, A.; Katz, R.; Gans, D.; Fan, Y.K.; Oyama, P. Intergenerational support and the emotional well-being of older Jews and Arabs in Israel. J. Marriage Fam. 2013, 75, 950–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD. Supporting Informal Carers of Older People. Policies to Leave No Carer Behind. 2022. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/0f0c0d52-en.pdf?expires=1724949092&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=EAE4A11C4AE2E8FD128D2A104514E0DD (accessed on 28 July 2024).

- Leigh, A. Informal care and labor market participation. Labour Econ. 2010, 17, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N | % | M | SD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Woman | 129 | 36.2% | ||

| Man | 227 | 63.8% | |||

| Age | 45–49 | 112 | 31.5% | 54.0 | 6.4 |

| 50–54 | 87 | 24.4% | |||

| 55–59 | 72 | 20.2% | |||

| 60–64 | 59 | 16.6% | |||

| 65–68 | 26 | 7.3% | |||

| Marital Status | Married | 285 | 80.1% | ||

| Single | 22 | 6.2% | |||

| Divorced | 45 | 12.6% | |||

| Widower | 4 | 1.1% | |||

| No. of Children a | 0 | 31 | 8.7% | 2.9 | 1.7 |

| 1 | 27 | 7.6% | |||

| 2 | 82 | 23.1% | |||

| 3 | 119 | 33.5% | |||

| 4 | 43 | 12.1% | |||

| 5–6 | 42 | 11.8% | |||

| 7–8 | 10 | 2.8% | |||

| 12 | 1 | 0.3% | |||

| Employment | Part-time employee | 52 | 14.6% | ||

| Full time employee | 254 | 71.3% | |||

| Self employed | 50 | 14.0% | |||

| Religiousness | Secular | 194 | 54.5% | ||

| Traditional | 116 | 32.6% | |||

| Religious | 36 | 10.1% | |||

| Very Religious | 10 | 2.8% | |||

| Education | High school | 27 | 7.6% | ||

| Professional training | 127 | 35.7% | |||

| Bachelor’s degree | 113 | 31.7% | |||

| Masters’ degree or higher | 89 | 25.0% | |||

| Income | 1500–9500 | 68 | 19.1% | 17,547 | 21,052 |

| 10,000–14,500 | 90 | 25.3% | |||

| 15,000–19,500 | 101 | 28.4% | |||

| 20,000–24,500 | 53 | 14.9% | |||

| 25,000–29,500 | 20 | 5.6% | |||

| 30,000 and above | 24 | 6.7% |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | Cronbach’s Alpha | M | SD | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Work demand 1 | 1 | 0.914 | 3.77 | 0.81 | 1–5 | ||||||

| 2. Caregiver burden 1 | 0.12 * | 1 | 0.885 | 2.24 | 0.67 | 1–5 | |||||

| 3. Work–family conflict total 2 | 0.24 ** | 0.33 ** | 1 | 0.914 | 2.40 | 0.89 | 1–5 | ||||

| 4. Work–family conflict time 2 | 0.22 ** | 0.30 ** | 0.88 ** | 1 | 0.883 | 2.36 | 1.05 | 1–5 | |||

| 5. Work–family conflict strain 2 | 0.21 ** | 0.34 ** | 0.91 ** | 0.77 ** | 1 | 0.886 | 2.41 | 1.03 | 1–5 | ||

| 6. Work–family conflict behavioral 2 | 0.19 ** | 0.21 ** | 0.80 ** | 0.51 ** | 0.58 ** | 1 | 0.842 | 2.42 | 1.01 | 1–5 | |

| 7. Exhaustion 2 | 0.22 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.65 ** | 0.55 ** | 0.66 ** | 0.47 ** | 1 | 0.869 | 2.86 | 1.36 | 1–7 |

| 8. Turnover intention 3 | 0.09 * | 0.11 * | 0.31 ** | 0.27 ** | 0.33 ** | 0.21 ** | 0.37 ** | 0.806 | 3.31 | 1.65 | 1–7 |

| Work–Family Conflict | Exhaustion | Turnover Intention | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | SE | 95% BC CI a | Effect | SE | 95% BC CI a | Effect | SE | 95% BC CI a | |

| Direct effects | |||||||||

| Caregiver burden | 0.41 | 0.07 | [0.26, 0.57] | −0.03 | 0.09 | [−0.19, 0.16] | −0.03 | 0.12 | [−0.27, 0.22] |

| Work demand | 0.21 | 0.06 | [0.10, 0.35] | 0.11 | 0.08 | [−0.04, 0.28] | −0.00 | 0.12 | [−0.22, 0.22] |

| Work–family conflict | – | – | – | 1.07 | 0.09 | [0.89, 1.26] | 0.31 | 0.17 | [−0.04, 0.58] |

| Exhaustion | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.30 | 0.09 | [0.12, 0.50] |

| Indirect effects | |||||||||

| Caregiver burden | – | – | – | 0.44 | 0.08 | [0.28, 0.61] | 0.25 | 0.07 | [0.13, 0.39] |

| Work demand | – | – | – | 0.23 | 0.07 | [0.10, 0.38] | 0.16 | 0.05 | [0.08, 0.28] |

| Work–family conflict | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.32 | 0.10 | [0.15, 0.55] |

| Total effects | |||||||||

| Caregiver burden | – | – | – | 0.41 | 0.10 | [0.22, 0.62] | 0.22 | 0.12 | [−0.03, 0.46] |

| Work demand | – | – | – | 0.33 | 0.09 | [0.16, 0.49] | 0.16 | 0.11 | [−0.07, 0.40] |

| Work–family conflict | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.63 | 0.13 | [0.37, 0.87] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vinarski-Peretz, H.; Mashiach-Eizenberg, M.; Halperin, D. Workforce Sustainability in Our Aging Society: Exploring How the Burden–Burnout Mechanism Exacerbates the Turnover Intentions of Employees Who Combine Work and Informal Eldercare. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7553. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16177553

Vinarski-Peretz H, Mashiach-Eizenberg M, Halperin D. Workforce Sustainability in Our Aging Society: Exploring How the Burden–Burnout Mechanism Exacerbates the Turnover Intentions of Employees Who Combine Work and Informal Eldercare. Sustainability. 2024; 16(17):7553. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16177553

Chicago/Turabian StyleVinarski-Peretz, Hedva, Michal Mashiach-Eizenberg, and Dafna Halperin. 2024. "Workforce Sustainability in Our Aging Society: Exploring How the Burden–Burnout Mechanism Exacerbates the Turnover Intentions of Employees Who Combine Work and Informal Eldercare" Sustainability 16, no. 17: 7553. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16177553